Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vertical Ownership in Media

Uploaded by

Shubham NagOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vertical Ownership in Media

Uploaded by

Shubham NagCopyright:

Available Formats

Vertical integration

In microeconomics and management, the term vertical integration describes a style of management control. Vertically integrated companies in a supply chain are united through a common owner. Usually each member of the supply chain produces a differentproduct or (market-specific) service, and the products combine to satisfy a common need. It is contrasted with horizontal integration. Vertical integration has also described management styles that bring large portions of the supply chain not only under a common ownership, but also into one corporation (as in the 1920s when the Ford River Rouge Complex began making much of its own steel rather than buy it from suppliers). Vertical integration is one method of avoiding the hold-up problem. A monopoly produced through vertical integration is called avertical monopoly. Nineteenth-century steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie's example in the use of vertical integration[1] led others to use the system to promote financial growth and efficiency in their businesses.

Three types

Vertical integration is the degree to which a firm owns its upstream suppliers and its downstream buyers. Contrary to horizontal integration, which is a consolidation of many firms that handle the same part of the production process, vertical integration is typified by one firm engaged in different parts of production (e.g. growing raw materials, manufacturing, transporting, marketing, and/or retailing). There are three varieties: backward (upstream) vertical integration, forward (downstream) vertical integration, and balanced (both upstream and downstream) vertical integration.

A company exhibits backward vertical integration when it controls subsidiaries that produce some of the inputs used in the production of its products. For example, an automobile company may own a tire company, a glass company, and a metal company. Control of these three subsidiaries is intended to create a stable supply of inputs and ensure a consistent quality in their final product. It was the main business approach of Ford and other car companies in the 1920s, who sought to minimize costs by integrating the production of cars and car parts as exemplified in the Ford River Rouge Complex. A company tends toward forward vertical integration when it controls distribution centers and retailers where its products are sold.

Examples

One of the earliest, largest and most famous examples of vertical integration was the Carnegie Steel company. The company controlled not only the mills where the steel was made, but also the mines where the iron ore was extracted, the coal mines that supplied the coal, the ships that transported the iron ore and the railroads that transported the coal to the factory, the coke ovens where the coal was cooked, etc. The company also focused

heavily on developing talent internally from the bottom up, rather than importing it from other companies. Later on, Carnegie even established an institute of higher learning to teach the steel processes to the next generation.

[2]

American Apparel

American Apparel is a fashion retailer and manufacturer that advertises itself as a vertically integrated industrial [3][4] company. The brand is based in downtown Los Angeles, where from a single building they control the dyeing, [4][5][6] finishing, designing, sewing, cutting, marketing and distribution of the company's product. The company shoots [3][7] and distributes its own advertisements, often using its own employees as subjects. It also owns and operates [8] each of its retail locations as opposed to franchising. According to the management, the vertically integrated model [9] allows the company to design, cut, distribute and sell an item globally in the span of a week. The original [10] founder Dov Charney has remained the majority shareholder and CEO. Since the company controls both the production and distribution of its product, it is an example of a balanced vertically integrated corporation.

Oil industry

Oil companies, both multinational (such as ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, ConocoPhillips or BP) and national (e.g. Petronas) often adopt a vertically integrated structure. This means that they are active along the entire supply chain from locating deposits, drilling and extracting crude oil, transporting it around the world, refining it into petroleum products such as petrol/gasoline, to distributing the fuel to company-owned retail stations, for sale to consumers.

Telephone

Telephone companies in most of the 20th century, especially the largest (the Bell System) were integrated, making their own telephones, telephone cables, telephone exchangeequipment and other supplies.

Reliance

The Indian petrochemical giant Reliance Industries has integrated back into polyester fibres from textiles and further into petrochemicals, beginning with Dhirubhai Ambani. Reliance has entered the oil and natural gas sector, along with retail sector. Reliance now has a complete vertical product portfolio from oil and gas production, refining, petrochemicals, synthetic garments and retail outlets.

Motion picture industry

From the early 1920s through the early 1950s, the American motion picture had evolved into an industry controlled by a few companies, a condition known as a "mature oligopoly". The film industry was led by Eight major film studios. The most powerful of these studios were the fully integrated Big Five studios: MGM, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox,Paramount Pictures, and RKO. These studios not only produced and distributed films, but also operated their own movie theaters. Meanwhile, the Little Three studios: Universal Studios, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists produced and distributed feature films, but did not own their own theaters.

The issue of vertical integration (also known as common ownership) has been a main focus of policy makers because of the possibility of anti-competitive behaviors affiliated with market influence. For example, in United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., the Supreme Court ordered the five vertically integrated studios to sell off their theater [11] chains and all trade practices were prohibited (United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 1948). The prevalence of [clarification needed] vertical integration wholly predetermined the relationships between both studios and networks and modified criteria in financing. Networks began arranging content initiated by commonly owned studios and stipulated a portion of the syndication revenues in order for a show to gain a spot on the schedule if it was produced by a studio [12] without common ownership. In response, the studios fundamentally changed the way they made movies and did business. Lacking the financial resources and contract talent they once controlled, the studies now relied on independent producers supplying some portion of the budget in exchange for distribution rights.

How Apple Made Vertical Integration Hot Again Too Hot, Maybe

Google recently acquired mobile-device maker Motorola Mobility and will soon manufacture smart phones and television set-top boxes. Amazons Kindle Fire tablet represents its bridge between hardware and e-commerce. Oracle bought Sun Microsystems and now champions engineered systems (integrated hardware-and-software devices). And even long-standing software giant Microsoft now makes hardware for its Xbox gaming system. Technology titans are increasingly looking like vertically integrated conglomerates largely in an attempt to emulate the success of Apple. Vertical integration dictates that one company controls the end product as well as its component parts. In technology, Apple for 35 years has championed a vertical model, which features an integrated hardware-and-software approach. For instance, the iPhone and iPad have hardware and software designed by Apple, which also designed its own processors for the devices. This integration has allowed Apple to set the pace for mobile computing. Despite the benefits of specialization, it can make sense to have everything under one roof, says Wharton management professor David Hsu. The tech industrys success in this type of integration is mixed. Samsung, a large technology conglomerate, has thrived by making everything from LCD panels to processors, televisions and smart phones. But Sony, which has attempted to meld content, TVs and game systems like the PlayStation, has yet to find a way to make the disparate parts gel. Companies can emulate the Apple model, but it will not happen overnight, notes Lawrence Hrebiniak, a Wharton management professor. Although tech companies for now are focusing on entering areas closely aligned with their core businesses, Hrebiniak notes that hardware and software require different competencies and skill sets in areas such as manufacturing,

procurement and supply chains. In that respect, the challenges these firms face will be similar to what many diversified multinationals deal with when managing disparate business units. The technology industrys rush to vertical integration may be misplaced, Hrebiniak says. After all, there is a reason that large conglomerates tend to trade at a discount on Wall Street they are harder to manage. Conglomerates can work if you have one line of business, go into another and then leave that unit alone, Hrebiniak notes. If you try to integrate disparate businesses, you become so unfocused that you lose the ability to coordinate. Yet, with technology companies under increasing pressure to keep growth rates up, expanding into new areas is an attractive proposition for many firms, according to Wharton new media director Kendall Whitehouse. Google may be getting into hardware today, but it could be Facebook tomorrow. Havent we seen this movie before? asks Whitehouse, pointing to the rise of multinational conglomerates in the mid-20th century. For example, Vivendi transformed itself from a water company to one focused on media, while GE started as an electric company but later expanded into such disparate businesses as microwave ovens and the NBC television network (which it recently sold to Comcast). Conglomerates are now refocusing after spreading themselves too thin, says Whitehouse. Can expanding tech companies learn the lessons of an earlier wave of conglomerates? There are also examples of tech firms that have switched gears and tried to return to a more specialized model. For instance, IBM divested its PC and printer operations to become a more service-focused company. The fundamental question about efforts to expand is whether there are synergies between these parts, notes Whitehouse. If a new product or service dovetails nicely with your core business, then there is something to leverage. If not, focus is better. According to experts at Wharton, markets that are not commoditized, such as mobile computing, smart phones and tablets, benefit most from vertical integration. However, once markets become less differentiated, a specialized approach where each member of a supply chain has a role makes sense. Hsu notes that the PC and semiconductor markets were once vertically integrated. Eventually, however, the supply chains reverted to being more specialized. In the case of PCs, a group of companies now makes different parts of the machine that are then put together to create the final product: Microsoft builds operating systems, Intel makes processors, Nvidia provides graphic chips and a series of companies manufactures hard drives. Looking Beyond Apple Envy

Googles plan is to operate Motorola Mobility as a separate business, which is tightly coupled to the Android mobile-operating system for smart phones and home set-top boxes. The trick for Google is making the key hardware-and-software connections to replicate Apples success. Apple does well, but has had top-down integration of hardware and software for more than 30 years, Hrebiniak states. That integration, which requires centralization foreign to Google and many other companies, is hard to deliver.

For example, Research in Motion also bought QNX, a company with an operating system and is trying to assimilate it with the firms hardware offerings, like the BlackBerry. But RIMs QNX-

based operating system has been delayed as the company struggled to sell the PlayBook tablet. Apples integration efforts were on display when the company unveiled its third-generation iPad last week. The new version will come with 4G connectivity, a high-definition display and a faster processor. Sterne Agee analyst Shaw Wu said in a research note that Apple had been able to advance features like power consumption precisely because it controlled the parts that make up the iPad. Our industry checks indicate Apple has made notable progress in improving battery life that has plagued competitors, said Wu. This is due to Apples ownership of core intellectual property including systems design, semiconductors, battery chemistry and software. According to Wharton management professor Dan Levinthal, what Apples competitors really envy is the companys control of its ecosystem. It is important to distinguish between a motivation to manage the interface between hardware and software and a desire to manage ones ecosystem. I think many of these moves are really about the latter sort of motivation, says Levinthal, who adds that Googles purchase of Motorola Mobility was not only a way to gain control of various patents, but also to fend off Apples patent lawsuits. Google also wants to create a more seamless user experience that will entice consumers to invest in its full line of products, rather than just using one or two, Levinthal notes. Analysts say Apples successes in this area led to increased market share. We believe that Apples software ecosystem (including third-party apps, iOS and Apples own applications) is the key to driving sales long term, Barclays Capital analyst Ben Reitzes said in a research note. There is just too much you can do with an iPad versus other devices. The Risk to Innovation

As technology companies push to become more vertically integrated, a few unpleasant side effects could emerge. For instance, Hsu suggests that the advancement and growth of Googles Android technology may slow if the company is juggling hardware and software efforts. Even though Android is technically open source, Google drives development. Google integration with Motorola Mobility could make products better, but the risk is that Android may not evolve at the same pace it would under a specialization model. Andrea Matwyshyn, a legal studies and business ethics professor at Wharton, has similar concerns. Vertical integration is desirable for some products, but you need multiple models in the technology industry, she says. If every tech company followed Apple, there would be a degree of novelty and innovation lost. After all, Apples success may be largely a function of a command and control structure instituted under former CEO Steve Jobs. If others followed suit, large technology companies would dominate supply chains and innovation, which could make it harder for a start-up to develop a breakthrough product. In some ways, you can make the case that more vertical integration could mean less innovation, Matwyshyn adds. Matwyshyn predicts that many technology companies currently trying to integrate software and hardware will back off in a few years. In 10 years, these companies are going to look a lot different, says Matwyshyn. Every industry has periods where vertical integration looks better. A few years ago, everyone was outsourcing.

Typically, companies back away from vertical integration as products become more commoditized. It is unclear when that will happen in the smart-phone or tablet markets, but the advent of that period would likely mean trouble for vertically integrated firms. What Apple has done well is stay ahead of commoditization, Hsu notes. Apple is more of a trailblazer and that opens up possibilities. The catch is that a vertical approach does not provide a significant advantage if a firm is unable to stay ahead of the competition. Indeed, Apples integrated approach in the PC market did not work to the firms benefit when it was battling Microsoft in the 1980s and 90s. In its current form, Apple has found a way to balance vertical integration with an outsourcing model. For instance, Apple focuses on design and integration, but Foxconn, a Chinese contract equipment manufacturer, actually puts together iPads and iPhones. According to Hsu, Apple has deployed a hybrid model, in which it has control over the product and supply chain but uses contractors in many areas. In addition, Hsu says, Apple is so large that it can dictate terms to contractors a leverage point that other technology companies cannot match.

You might also like

- The Templist Scroll by :dr. Lawiy-Zodok (C) (R) TMDocument144 pagesThe Templist Scroll by :dr. Lawiy-Zodok (C) (R) TM:Lawiy-Zodok:Shamu:-El100% (5)

- Teacher Manual Economics of Strategy by David BesankoDocument227 pagesTeacher Manual Economics of Strategy by David BesankoCéline van Essen100% (4)

- Besanko HarvardDocument228 pagesBesanko Harvardkjmnlkmh100% (1)

- Cross Media OwnershipDocument14 pagesCross Media OwnershipShubham NagNo ratings yet

- 73ac4horizontal & Vertical IntegrationDocument5 pages73ac4horizontal & Vertical IntegrationOjasvee KhannaNo ratings yet

- DK Children Nature S Deadliest Creatures Visual Encyclopedia PDFDocument210 pagesDK Children Nature S Deadliest Creatures Visual Encyclopedia PDFThu Hà100% (6)

- Horizontal and Vertical IntegrationDocument9 pagesHorizontal and Vertical IntegrationAmna Rasheed100% (1)

- Book Solution Economics of Strategy Answer To Questions From The Book Also Relevant For Later Editions of The BookDocument229 pagesBook Solution Economics of Strategy Answer To Questions From The Book Also Relevant For Later Editions of The Bookvgfalcao84100% (2)

- WL 318 PDFDocument199 pagesWL 318 PDFBeckty Ahmad100% (1)

- Elevator Traction Machine CatalogDocument24 pagesElevator Traction Machine CatalogRafif100% (1)

- Innovation in VolkswagenDocument7 pagesInnovation in VolkswagenpwmarinelloNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Market IntegrationDocument9 pagesChapter 3 Market IntegrationJeandy Baniaga100% (2)

- The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production-- Toyota's Secret Weapon in the Global Car Wars That Is Now Revolutionizing World IndustryFrom EverandThe Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production-- Toyota's Secret Weapon in the Global Car Wars That Is Now Revolutionizing World IndustryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Market IntegratonDocument6 pagesMarket IntegratonUmekoNo ratings yet

- Types of Newspaper Ownership in IndiaDocument3 pagesTypes of Newspaper Ownership in IndiaShubham Nag96% (24)

- Vertical and Horizontal IntegrationDocument19 pagesVertical and Horizontal IntegrationStone Cold67% (3)

- Juan Martin Garcia System Dynamics ExercisesDocument294 pagesJuan Martin Garcia System Dynamics ExercisesxumucleNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management 2Document10 pagesMarketing Management 2Pankaj YadavanNo ratings yet

- Global Alliances and Strategy ImplementationDocument7 pagesGlobal Alliances and Strategy ImplementationBogdan Alexandru Dida100% (2)

- Strategic Management Concepts for Professionals (38 charactersDocument6 pagesStrategic Management Concepts for Professionals (38 charactersoumar06No ratings yet

- Box 4a p2 of 8 Market IntegrationDocument7 pagesBox 4a p2 of 8 Market IntegrationDanica De VeraNo ratings yet

- M&a PresentationDocument44 pagesM&a Presentationapps175No ratings yet

- Corporate Strategy Building Blocks for Superior Firm PerformanceDocument5 pagesCorporate Strategy Building Blocks for Superior Firm PerformanceZaffar KhanNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Warehousing: Facing The Forces of Change Lean Supply ChainDocument6 pagesInnovation in Warehousing: Facing The Forces of Change Lean Supply ChainDarienny Rijo CatanoNo ratings yet

- Synp 02 Growth Through Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument14 pagesSynp 02 Growth Through Mergers and AcquisitionsSamman GuptaNo ratings yet

- Name: Zaffar-Ul-Lah Khan Class: Bba Vi Sec: (Ii) GR#: 252066Document7 pagesName: Zaffar-Ul-Lah Khan Class: Bba Vi Sec: (Ii) GR#: 252066Adeel Shafique KhawajaNo ratings yet

- Activity "2": 1: Market Penetration:: Telecom Industry Company"Document4 pagesActivity "2": 1: Market Penetration:: Telecom Industry Company"Rahul DusejaNo ratings yet

- Dalrymples Sales Management Concepts and Cases 10th Edition Cron Solutions ManualDocument5 pagesDalrymples Sales Management Concepts and Cases 10th Edition Cron Solutions Manualcommenceingestah7nxd9100% (22)

- A Systems Perspective On The Death of A Car Company: Ijopm 28,6Document23 pagesA Systems Perspective On The Death of A Car Company: Ijopm 28,6JOGA SINGHNo ratings yet

- Technology StrategyDocument18 pagesTechnology StrategyYatin Gupta50% (2)

- Globalization Stages and IndustriesDocument6 pagesGlobalization Stages and IndustriesMohsin JuttNo ratings yet

- BDNG3103 Introductory International Business - Smay19 (RS - MREP) (010-259) Split (013-013)Document1 pageBDNG3103 Introductory International Business - Smay19 (RS - MREP) (010-259) Split (013-013)frizalNo ratings yet

- Mergers Acquisitions and Corporate Restructuring-IIDocument57 pagesMergers Acquisitions and Corporate Restructuring-IIPRAO600583% (6)

- Economics of Strategy (Rješenja)Document227 pagesEconomics of Strategy (Rješenja)Antonio Hrvoje ŽupićNo ratings yet

- Case 2-3Document20 pagesCase 2-3Rif Fa'iNo ratings yet

- Vertical IntegrationDocument4 pagesVertical IntegrationFatima FaisalNo ratings yet

- IJV MARLEY AutomotiveDocument6 pagesIJV MARLEY AutomotiveUmer HamidNo ratings yet

- English For Business - Stulent's BookDocument3 pagesEnglish For Business - Stulent's BookjlcamargomadridistaNo ratings yet

- Basic Types of Organizational StructuresDocument7 pagesBasic Types of Organizational StructuresJomy AugustineNo ratings yet

- 8503 1Document10 pages8503 1Sana MajeedNo ratings yet

- Monopoly Real Life Examples: Example 1Document7 pagesMonopoly Real Life Examples: Example 1Rafia MalikNo ratings yet

- Types of M&ADocument31 pagesTypes of M&Adhruv vashisth100% (1)

- Monopoly Real Life Examples: Example 1Document7 pagesMonopoly Real Life Examples: Example 1Rafia MalikNo ratings yet

- MergersDocument6 pagesMergersnafees.shaikh6686No ratings yet

- Lesson 4 - SM 1 Types of StrategiesDocument8 pagesLesson 4 - SM 1 Types of StrategiesJennie KimNo ratings yet

- CH 6Document6 pagesCH 6rachelohmygodNo ratings yet

- C11: Understanding Horizontal BoundariesDocument76 pagesC11: Understanding Horizontal BoundariesKhyati GuptaNo ratings yet

- Week 1: Introduction To Operations Strategy: QUESTION - "Many Organisations in Many Industries Claim To BeDocument5 pagesWeek 1: Introduction To Operations Strategy: QUESTION - "Many Organisations in Many Industries Claim To BeJakeNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Modern Firm: Chapter ContentsDocument14 pagesThe Evolution of The Modern Firm: Chapter Contentsleisurelarry999No ratings yet

- Alliance School Business Strategy AssignmentsDocument5 pagesAlliance School Business Strategy AssignmentsanandasnuNo ratings yet

- The Final SolutionDocument13 pagesThe Final Solutionaksharma36No ratings yet

- Types of MergersDocument13 pagesTypes of MergersJebin JamesNo ratings yet

- mergers and acquisition mba final notesDocument60 pagesmergers and acquisition mba final notestarunNo ratings yet

- Business CombinationDocument18 pagesBusiness CombinationJoynul AbedinNo ratings yet

- Ford CaseDocument21 pagesFord Casemansdeal100% (3)

- Chapter 9 - Alternatives To M&ADocument29 pagesChapter 9 - Alternatives To M&AkiranaishaNo ratings yet

- Corporate StrategyDocument5 pagesCorporate StrategyMihir HariaNo ratings yet

- BSM 495 International CaseDocument6 pagesBSM 495 International CaseTammy ManuelNo ratings yet

- Full Project AnjanaDocument59 pagesFull Project AnjanaMK gamingNo ratings yet

- CRV Module 1Document24 pagesCRV Module 1Iranshah MakerNo ratings yet

- Matching Strategy To A Company's SituationDocument23 pagesMatching Strategy To A Company's SituationImron RosyadiNo ratings yet

- Competing With Dual Business Models - A Contingency ApproachDocument17 pagesCompeting With Dual Business Models - A Contingency ApproachCaio PeretNo ratings yet

- NIFT Patna assignment explores strategic management examplesDocument8 pagesNIFT Patna assignment explores strategic management examplesRitu RajNo ratings yet

- Volvo and Renault's Proposed MergerDocument15 pagesVolvo and Renault's Proposed MergerMaitrayaNo ratings yet

- Ford's Supply Chain Strategy for Adapting to Emerging TechnologiesDocument9 pagesFord's Supply Chain Strategy for Adapting to Emerging TechnologiesDavid ThambuNo ratings yet

- GU 02 Globalization and Its Effect On Global Supply Chain ManagementDocument4 pagesGU 02 Globalization and Its Effect On Global Supply Chain ManagementTanmayNo ratings yet

- X and Y Theory of ManagementDocument1 pageX and Y Theory of ManagementShubham NagNo ratings yet

- Who Owns The Media in IndiaDocument2 pagesWho Owns The Media in IndiaShubham Nag100% (2)

- Ownership TypesDocument16 pagesOwnership TypesShubham Nag50% (2)

- Organizational Structure of Media Co.Document9 pagesOrganizational Structure of Media Co.Shubham NagNo ratings yet

- Murdhochisation of Indian MediaDocument13 pagesMurdhochisation of Indian MediaShubham NagNo ratings yet

- Proposed Broadcast BillDocument1 pageProposed Broadcast BillShubham NagNo ratings yet

- Organisational Structure of AIRDocument10 pagesOrganisational Structure of AIRShubham Nag75% (4)

- Grave Danger in Cross Media OwnershipDocument2 pagesGrave Danger in Cross Media OwnershipShubham NagNo ratings yet

- Indian Govt Control On MediaDocument3 pagesIndian Govt Control On MediaShubham NagNo ratings yet

- Concentration of Media OwnershipDocument9 pagesConcentration of Media OwnershipShubham NagNo ratings yet

- Malaviya's Ideal JournalismDocument1 pageMalaviya's Ideal JournalismShubham NagNo ratings yet

- Press Trust of IndiaDocument2 pagesPress Trust of IndiaShubham NagNo ratings yet

- De Thi HSG Tinh Binh PhuocDocument9 pagesDe Thi HSG Tinh Binh PhuocDat Do TienNo ratings yet

- KAC-8102D/8152D KAC-9102D/9152D: Service ManualDocument18 pagesKAC-8102D/8152D KAC-9102D/9152D: Service ManualGamerAnddsNo ratings yet

- Pitch Manual SpecializedDocument20 pagesPitch Manual SpecializedRoberto Gomez100% (1)

- JUPITER 9000K H1PreliminaryDocument1 pageJUPITER 9000K H1PreliminaryMarian FlorescuNo ratings yet

- Current Relays Under Current CSG140Document2 pagesCurrent Relays Under Current CSG140Abdul BasitNo ratings yet

- Diia Specification: Dali Part 252 - Energy ReportingDocument15 pagesDiia Specification: Dali Part 252 - Energy Reportingtufta tuftaNo ratings yet

- Usjr Temfacil Balance of Work Schedule Aug 25, 2022Document5 pagesUsjr Temfacil Balance of Work Schedule Aug 25, 2022Maribeth PalumarNo ratings yet

- Letter of MotivationDocument4 pagesLetter of Motivationjawad khalidNo ratings yet

- Rectifiers and FiltersDocument68 pagesRectifiers and FiltersMeheli HalderNo ratings yet

- Sto - Cristo Proper Integrated School 1 Grading Grade 9 Science Table of SpecializationDocument2 pagesSto - Cristo Proper Integrated School 1 Grading Grade 9 Science Table of Specializationinah jessica valerianoNo ratings yet

- 1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDDocument81 pages1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDJerome Samuel100% (1)

- VA TearDownDocument5 pagesVA TearDownfaj_larcfave5149No ratings yet

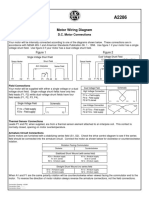

- Motor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor ConnectionsDocument1 pageMotor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor Connectionsczds6594No ratings yet

- Magnetic Pick UpsDocument4 pagesMagnetic Pick UpslunikmirNo ratings yet

- Application of Fertility Capability Classification System in Rice Growing Soils of Damodar Command Area, West Bengal, IndiaDocument9 pagesApplication of Fertility Capability Classification System in Rice Growing Soils of Damodar Command Area, West Bengal, IndiaDr. Ranjan BeraNo ratings yet

- 中美两国药典药品分析方法和方法验证Document72 pages中美两国药典药品分析方法和方法验证JasonNo ratings yet

- Update On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Document7 pagesUpdate On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Sebastian DeMarinoNo ratings yet

- Answer Key p2 p1Document95 pagesAnswer Key p2 p1Nafisa AliNo ratings yet

- Conjoint Analysis Basic PrincipleDocument16 pagesConjoint Analysis Basic PrinciplePAglu JohnNo ratings yet

- The Art of Now: Six Steps To Living in The MomentDocument5 pagesThe Art of Now: Six Steps To Living in The MomentGiovanni AlloccaNo ratings yet

- Features Integration of Differential Binomial: DX BX A X P N MDocument4 pagesFeatures Integration of Differential Binomial: DX BX A X P N Mابو سامرNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Employees' Commitment Towards Food Safety at Ayana Resort, BaliDocument58 pagesThe Impact of Employees' Commitment Towards Food Safety at Ayana Resort, Balirachelle agathaNo ratings yet

- Elements of ClimateDocument18 pagesElements of Climateእኔ እስጥፍNo ratings yet

- Material and Energy Balance: PN Husna Binti ZulkiflyDocument108 pagesMaterial and Energy Balance: PN Husna Binti ZulkiflyFiras 01No ratings yet

- Advanced Ultrasonic Flaw Detectors With Phased Array ImagingDocument16 pagesAdvanced Ultrasonic Flaw Detectors With Phased Array ImagingDebye101No ratings yet