Professional Documents

Culture Documents

British Museum Australia Exhibit

Uploaded by

api-238501268Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

British Museum Australia Exhibit

Uploaded by

api-238501268Copyright:

Available Formats

10/11/13 British Museum and National Museum of Australia host dual indigenous exhibition | The Australian

www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/the-collectors/story-fn9n8gph-1226731746376 1/5

British Museum and National Museum oI Australia host dual

indigenous exhibition

IT is 97cm long, 29cm wide and has a ragged hole near its centre. Made from the bark of the spotted mangrove tree,

the "elemong" shield has few distinctive features, yet it is a rare and potent symbol of the first, tense moments of

contact between Europeans and Aborigines on Australia's east coast.

Thought to have been made by the Gweagal people, this deIensive weapon transports us back to that Iraught autumn day in

1770 when crew members Irom the HMB Endeavour, working under the command oI James Cook, tried to land at Botany

Bay but were challenged by two Aboriginal men.

The Aborigines had rejected Cook's oIIerings oI nails and beads, and the explorer resorted to violence, Iiring at them with

his musket. He injured one oI the men, who showed remarkably little Iear. The expedition's botanist, Joseph Banks, took up

the story in his journal:

A man who attempted to oppose our Landing came down to the Beach with a shield ... this he leIt behind when he ran

away, and we Iound upon taking it up that it plainly had been piercd through with a single pointed lance near the centre.

This shield has been in the British Museum's collection since 1771. It carries enormous historical signiIicance Ior

Australians, yet it has never been exhibited here.

That is likely to change, however, when the British Museum and National Museum oI Australia stage a highly ambitious

project: linked exhibitions in London and Canberra based on key objects Irom the BM's Australian indigenous collection.

The Canberra exhibition will mark the Iirst time these arteIacts have been back in Australia since colonial collectors obtained

them as giIts, objects oI trade or - more controversially - in the aItermath oI violent conIlict.

NMA acting director Mathew Trinca says the exhibitions are the most important project the National Museum has worked

on in years. "It quickly became clear to us that this wasn't just an exhibition," he tells Review.

"It is an entire program oI work. I think, honestly, that this is the most important work we're doing this decade.

THE AUSTRALIAN

ROSEMARY NEILL THE AUSTRALAN OCTOBER 05, 2013 12:00AM

National Museum of Australia adviser Henrietta Formile Marrie believes some artefacts in the British Museum collection should be returned to Australia. Picture:

Brian Cassey Source: TheAustralian

Contemporary artworks for the British Museum exhibition. Source: Supplied

facebooktwitterlinkedingoogleredditemail

facebook

twitter

linkedin

google

reddit

email

Sh

Sh

10/11/13 British Museum and National Museum of Australia host dual indigenous exhibition | The Australian

www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/the-collectors/story-fn9n8gph-1226731746376 2/5

"There's also a national debate that we're Iostering about what this material is, what meaning it has Ior all Australians, as

well as reconnecting indigenous people around the country to what in many cases is the earliest material, extant, that

originated Irom their communities."

For Trinca, a man unaIraid oI loIty rhetoric, the Cook shield alone has untold signiIicance. "That shield we believe to be

remarkable," he says during an interview in his large uncluttered Canberra oIIice, "because it stands at the epicentre oI what

then Iollows. The misapprehension, the conIusion, that Iirst meeting between the Aboriginal people oI the Botany Bay area

and Cook, stands somewhat as an emblem oI a whole series oI encounters that take place across the continent in succeeding

years."

It is anticipated the shield will be exhibited at the NMA alongside Iour spears also acquired Irom Botany Bay, and on loan

Irom the Cambridge Museum oI Archaeology and Anthropology.

The joint project is aIIording NMA staII unprecedented access to the BM's treasures, widely regarded as the world's most

signiIicant collection oI Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander arteIacts Irom the early days oI British settlement.

British Museum director Neil MacGregor tells Review: "I think a London audience will be astounded by the beauty and

signiIicance oI these objects and I hope they will be moved and impressed by what they learn about the deep history and

contemporary vitality oI Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islands cultures.

"I am delighted that we will then lend many objects to the National Museum oI Australia, where both indigenous

Australians and others can view this material."

The linked exhibitions will likely open in 2015 - one at the BM and the other at the NMA on the shores oI Lake Burley

GriIIin. By then, Iive years oI cross-continental collaboration, research and consultation will have gone into the shows.

While they will employ diIIerent curators and the Iinal list oI objects has yet to be conIirmed, both will include weapons,

jewellery and utensils collected as the Iirst waves oI European exploration and settlement broke across the country, Irom

Cook's landing at Botany Bay, to bloody Irontier skirmishes in north Queensland and the Kimberley, to surprisingly

amicable exchanges in the embryonic West Australian colony.

Aboriginal leader Peter Yu, who is on the NMA's indigenous advisory committee, agrees the Canberra exhibition will be "a

milestone exhibition in the history oI the nation".

"I think it'll be a highly emotional one in terms oI what the cultural material represents in terms oI Iirst contact and

subsequent relationships," he says. "It will also provide greater insight into, and a reconnection to, the circumstances and

context oI the materials' origins ... Overall, I think this is potentially very signiIicant as a major reconciliation event."

Yu explains while reconciliation has been happening in Australia Ior some time, there has never been an event that Iocuses

on indigenous people's relations with early settlers and the British crown.

Already, the project is generating the biggest consultation with indigenous communities in the NMA's history. NMA and

BM curators have Ianned out to 15 indigenous communities covering every state and territory, Irom Albany in the southwest

to the Iar-Ilung Torres Strait Islands, in a bid to inIorm indigenous communities about objects that came Irom their regions.

In several cases, communities were astounded to learn arteIacts potentially made or owned by their ancestors were in the

BM collection.

And some activists are demanding those objects be repatriated to their original communities. NMA adviser Henrietta

Fourmile Marrie says she was overwhelmed to discover recently the BM has jewellery collected in Cairns in the 1890s that

is strikingly similar to a shell ornaments worn by her great-grandIather, Ye-i-nie, in a historic photograph.

Ye-i-nie was an inIluential community leader and the 1905 photograph shows a slight man oI regal bearing, his initiation

scars visible across his torso. He holds a heIty wooden shield and wears a shell headband, hairband and pendant, as well as

a large breastplate engraved with the words "Ye-i-nie/King oI Cairns/1905".

Marrie argues BM arteIacts Irom the Cairns region - among them shields with distinctive rainIorest designs and a message

stick on which a Iather commemorates the death oI his daughter - should be returned to the area or, Iailing that, put into

temporary custodianship at the NMA.

"Why do the British Museum want them?" she demands, her voice soIt yet insistent. "It has no relevance to them as a

people. It has no relevance to their culture; it has more importance Ior us here."

A Yidinji woman with empathetic brown eyes and a quietly determined manner, Marrie has worked Ior the UN and has

been a cultural rights campaigner Ior several decades. She points out when Aboriginal communities were dispossessed oI

their land, they were also dispossessed oI their cultural heritage.

Moreover, the victors not only write the history, they oIten keep the spoils oI that history. For these reasons, she argues the

BM arteIacts - many oI which are rarely on public display - eventually should be repatriated so contemporary Aborigines

"and the next generation can understand more about who they are as a people, and who they are as a nation".

Dennis Ah-Khee, a traditional landowner Irom north Queensland, agrees "those |BM| collections should come back into

this country". He says emphatically: "II the British Museum wants copies oI those arteIacts, we can produce them ourselves

and send them |the copies| back."

Ah-Khee says museums oIten Iail to comprehend the spiritual and emotional value oI indigenous objects. "I know a lot oI

our old people, iI those arteIacts come back here, they will cry, right, they will cry. We regard them as living things. They're

a part oI our history."

However, Torres Strait Islander Lui Ned David sees the issue diIIerently. He too has sat in on an NMA consultation and he

says oI the linked exhibitions: "I'm all Ior it, in many ways. It showcases us as two indigenous races to the rest oI the world,

and to our country. It tells a story.

10/11/13 British Museum and National Museum of Australia host dual indigenous exhibition | The Australian

www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/the-collectors/story-fn9n8gph-1226731746376 3/5

"More importantly, Ior us as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, I honestly believe there's a sense oI pride. It showcases

to us the good and bad |history|, there's some truth about it.

"Something on this scale Irom one oI the most prominent institutions on the planet - you don't ignore something like that,

and you don't try and do away with it. I think you embrace it."

The Tudu Islander was equally chuIIed when a spectacular crocodile dance mask, made Irom a metal saw, Ieathers and

turtleshell by his great-grandIather in the 1880s, was displayed prominently in the BM Ioyer in London two years ago. The

mask, he explains, was given by his great-grandIather, Maino, to British researcher AlIred Haddon, who in turn, donated it

to the museum. "It was a giIt; something Ior them to put on display so the rest oI the world would know about this great

warrior and chieI |David's great-great-grandIather|. I'm quite proud about it." In sharp contrast, David says he recently had

an "unbelievably painIul" experience with the BM. A co-chairman oI the Iederal government's advisory committee Ior

indigenous repatriation, he had campaigned Ior the return oI two Torres Strait Islander skulls Irom the BM. Although this

claim was supported by the recently deposed Iederal Labor government, the BM rejected it late last year.

"It |the decision| was downright one-sided Ior all the wrong reasons," says David, his voice quivering with emotion.

The skulls were acquired by Haddon and donated to the BM in 1889. David argues: "These are human remains. They

belong to my people and we are asking iI we can please have them back so we can give them a decent burial." He says the

skulls will not be publicly exhibited - museums would rarely, iI ever, display human remains these days - and are oI no

scientiIic use to the BM.

The BM decision resists the international trend Ior museums to return human remains to indigenous claimants, but the

museum's deputy director, Jonathan Williams, maintains "the trustees gave very careIul consideration to the claim". In

rejecting it, the board argued Haddon's acquisition did not interrupt mortuary processes, as TSI skulls were traded in the 19th

century.

The trustees also concluded public beneIit was best served by the museum retaining the skulls. While David remains a

strong supporter oI the Iorthcoming twin exhibitions, Ior him, there is a whiII oI hypocrisy about the spurned claim. The

BM, he says, has "reIused our claim. On the other hand, they are aIter our collaboration."

THE working title oI the NMA show is Encounters and, in a sense, the historical stories oI how the collected objects

brought whites and blacks together - in Iriendship, commerce and battle - are as revealing as the arteIacts themselves.

Indeed, Ian Coates, the NMA staII member who came up with the idea Ior the joint project, says these objects have "the

potential to change how we all understand Australian history".

Coates, co-lead curator oI Encounters, says the BM arteIacts "demonstrate the longevity oI Australia's indigenous people's

history in a way that words cannot ... They show that there is no single, easy narrative that describes Australia's colonial

past. The Irontier was messy, at times it was violent, at times there was Iriendship."

Certainly, the stories oI how the objects were collected suggest a broader spectrum oI relationships between European

settlers and indigenous people than conventional narratives oI white oppressors and passive black victims allow.

When Scottish pioneer and surgeon Alexander Collie met young Minang leader Mokare in Western Australia in the early

19th century, Iew could have imagined how close the two - separated by language and cultural diIIerences and the period's

cast-iron racial prejudices - would become. Collie had sailed alongside lieutenant-governor James Stirling to help establish

the Swan River Colony in 1829 and was appointed the Iirst government resident oI King George Sound (near Albany) in

1831. Mokare was Collie's interpreter and guide, and the two men became so attached that aIter each died prematurely, Irom

diIIerent illnesses, they were buried side by side in a makeshiIt graveyard.

Collie was also a collector and the arteIacts he gathered, probably with Mokare's help, are in the BM collection. Among

them are a spearthrower and Iearsome-looking axe.

Other exhibits conjure a more conIrontational history: one oI Iierce indigenous resistance to a relentlessly advancing Irontier

oI European occupation; oI attacks on colonial settlers Iollowed by Iar bloodier reprisals. Objects Irom the Kimberley

including an iron axe and glass-headed spear can be traced back to one oI the most inIamous police pursuits oI the colonial

era: the three-year hunt Ior Jandamarra.

Sometimes known as the Aboriginal Ned Kelly, Jandamarra led an armed uprising against European settlement and the

police in the 1890s aIter he killed a white policeman.

A hunting net and shields collected by sugar industry pioneer John Ewen Davidson speak oI Iurther Aboriginal resistance to

European colonisation in north Queensland in the 1860s and 70s. In 1866, Davidson wrote in his diary about the paralysing

terror oI an Aboriginal child caught up in an armed police raid: "One little girl took reIuge under my horse's belly and could

not move." The raid was a reprisal Ior local Aborigines' attacks on white settlers near Cardwell. Davidson observed: "It was

a strange and painIul sight to see a human being running Ior his liIe and see the black police galloping aIter him and hear the

crack oI the carbines."

As the conIlict continued, the cane Iarmer's attitudes towards Aborigines rapidly hardened. Just Iive months aIter he wrote

so movingly about the terriIied girl, he shot at two large groups advancing on his camp. "We Iollowed them up into the

scrub Iiring at them as they went," he wrote on June 24, 1866. "Some were wounded, but I saw some killed: there was

plenty oI blood on one or two shields which we picked up."

As Davidson's diary shows, some objects collected and donated to the BM - and which are likely to be shown in Encounters

- were acquired amid lethal violence, under circumstances that today would be considered unethical.

Should such items eventually be returned to their source communities? Or does the Iormidable reputation and reach oI the

BM - in eIIect, a universal exhibition and research centre - override such considerations? The vexed issues oI ownership and

10/11/13 British Museum and National Museum of Australia host dual indigenous exhibition | The Australian

www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/the-collectors/story-fn9n8gph-1226731746376 4/5

custodianship will be addressed at a conIerence the NMA plans to hold in tandem with the Canberra exhibition. Trinca says:

"The whole reason we're doing this is to open out the possibility oI having this discussion productively, Ior the nation."

Certainly, recent legislation means there will be no repeat oI a dispute that erupted in 2004, when Aboriginal activists in

Victoria took out a cultural protection order to stop three touring indigenous exhibits - a ceremonial headdress owned by the

Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, and two bark etchings Irom the BM - returning to Britain. Amid warnings that seizure would

put Iuture museum loans to Australia at risk, the Federal Court overturned the protection order and the indigenous exhibits

were returned to Britain.

A new Iederal law means touring arteIacts and artworks are insulated Irom attempts to keep them here; some believe this

legislation was passed with Encounters in mind.

Intriguingly, the NMA's consultations are already overturning mistaken assumptions about some arteIacts held by the august

London institution Ior more than a century. In north Queensland, amused indigenous people declared a hunting net collected

by Davidson and classiIied as a kangaroo net was actually a brush turkey net. In the Torres Strait, islanders told visiting

NMA staII that an object listed on the BM website as a charm was part oI a headhunting kit, while an arteIact listed as a

chest pendant was a pubic shell cover.

The NMA cross-checked these claims, and Iound the locals' observations were spot-on.

The NMA's Coates made a Iurther, stunning discovery about what many say is an under-researched collection. While on a

curatorial exchange with the BM, he spotted several watercolours - one Ieatured masked, grass-skirted men dancing around

a campIire - oI late 19th-century Torres Strait Islander liIe. The drawings were signed T. Roberts.

Coates guessed these were the work oI celebrated Australian painter Tom Roberts, something the British had not realised.

Still palpably excited, the curator says: "IdentiIying the Roberts drawings was deIinitely something oI a eureka moment - it

was, 'No, it couldn't be,' Iollowed by, 'Could it be?' - and then the excitement oI realising that these were by him, and that

they were a previously unknown body oI work which complemented his rich published account oI his time in the Torres

Strait." The BM and NMA now suspect there is a Roberts oil painting oI one oI these scenes in private hands and are keen

to hear Irom the owner.

Gaye Sculthorpe, who is curating the London show, concedes "a lot oI the collection has not been adequately researched or

published". But she says the research being poured into the linked exhibitions is helping to change this.

Digitisation oI the collection, she says, is giving researchers, including indigenous researchers in Australia, enhanced access

to it.

Sculthorpe is the Iirst indigenous Australian to win a staII job at the BM, and she says while the London exhibition will

include the colonial stories that Irame the exhibits, it will also Iocus on the objects' histories beIore white settlement. "These

objects don't just have one story to tell, they have many stories to tell," she says.

Both the Canberra and London exhibitions will include contemporary indigenous artworks, a statement about how

indigenous culture, Iar Irom being snap-Irozen, continues to evolve. Sculthorpe explains: "One oI the important messages oI

the London exhibition is to emphasise that the objects held by the museum, whether they're Irom the early colonial period or

contemporary objects, reIlect a living, diverse and dynamic culture. It's not a relic oI the past."

Abe Muriata, a Girramay man Irom the Cardwell area, is living evidence oI that. A painter and shield-maker with a big-

brimmed Akubra and a playIul sense oI humour, Muriata spent years teaching himselI a traditional art that was endangered

in his community. It took him three years to make his Iirst bicornual basket - an elegant, bell-bottomed aIIair unique to the

rainIorest people oI Queensland - and he largely achieved this by studying historical examples in Queensland museums.

Muriata argues museums help invigorate indigenous culture by conserving arteIacts and records oI cultural practices

undermined by government policy. "Many years ago in Queensland, a lot oI our people were removed |to government-run

settlements|, and it broke the tradition oI passing down the skills needed to manuIacture a lot oI the arteIacts," he explains.

A weaver oI 10 years' standing, Muriata has had his baskets exhibited in the Queensland Art Gallery and South Australian

Museum, and he is passing on his skills to others.

"I'm getting better all the time," he says. "This is not a trade you just pick up on a whim and say, 'I'm gonna make a basket'.

It took me three years to make my Iirst basket, and even then it was not top-quality stuII."

Like Muriata, Marrie has unearthed important aspects oI her heritage (a recording oI her grandIather speaking his traditional

language, a Iamily genealogy dating back to the 1860s) in Australian museums.

But unlike the selI-taught weaver, she is indignant she and her extended Iamily would have remained ignorant oI this rich

history iI she had not sought it out. She Ieels strongly that lost or broken traditions could be rekindled iI indigenous

communities had better access to old photographs, Iamily histories or language tapes held by museums.

The revelation the BM has shell jewellery that closely resembles that worn by her great-grandIather continues her

ambivalent journey oI discovery - the pleasure oI recognition, Iollowed by disappointment she didn't know about this trove

oI traditional treasures earlier. "We were quite overwhelmed by the amount oI our cultural heritage that is in the museum,"

she says. "Not just the arteIacts, but the written inIormation about them that is so crucial to our cultural existence and our

cultural survival."

Marrie has long campaigned Ior indigenous people to be better inIormed about the material museums hold about them,

writing in a 1992 paper: "The current situation regarding our heritage is a mess." She tells Review things have "improved

slightly" since then, and she applauds the NMA and BM consultations.

"It's great they have decided that the way Iorward is to have consultations with the communities where these objects and

cultural materials come Irom," she says. "It's something that's been missing Ior many, many years. Museums have never

really gone out there and consulted on the ground, so it's nice to see that shiIt in thinking."

You might also like

- The Future of Indigenous Museums: Perspectives from the Southwest PacificFrom EverandThe Future of Indigenous Museums: Perspectives from the Southwest PacificNick StanleyNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal Australia: Discover..Document9 pagesAboriginal Australia: Discover..RQL83appNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 130.56.64.101 On Sat, 27 Feb 2021 05:31:34 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 130.56.64.101 On Sat, 27 Feb 2021 05:31:34 UTCsofiaNo ratings yet

- A Cultural History of the Bushranger Legend in Theatres and Cinemas, 18282017From EverandA Cultural History of the Bushranger Legend in Theatres and Cinemas, 18282017No ratings yet

- Black History Month 2009Document35 pagesBlack History Month 2009kingrockerNo ratings yet

- The Long Way Home: The Meaning and Values of RepatriationFrom EverandThe Long Way Home: The Meaning and Values of RepatriationPaul TurnbullNo ratings yet

- Rehanging Australian Art to Reflect Indigenous PerspectivesDocument7 pagesRehanging Australian Art to Reflect Indigenous PerspectivesWajeeha NafeesNo ratings yet

- The Australian RegisterDocument188 pagesThe Australian Registerdimitra rNo ratings yet

- Australian Aborigines Demand Return of RemainsDocument1 pageAustralian Aborigines Demand Return of RemainsDgl SupriyadiNo ratings yet

- (04a) The Battle For Hearts and Minds - Using Soft Power To Undermine Terrorist Networks (Book Review by Bellamy)Document33 pages(04a) The Battle For Hearts and Minds - Using Soft Power To Undermine Terrorist Networks (Book Review by Bellamy)beserious928No ratings yet

- Antipodean Currents Ten Contemporary Artists From AustraliaDocument162 pagesAntipodean Currents Ten Contemporary Artists From Australiarollthebones11No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Australia: Early Indigenous PrehistoryDocument2 pagesAboriginal Australia: Early Indigenous PrehistorymosesNo ratings yet

- History, heritage, and colonialism: Historical consciousness, Britishness, and cultural identity in New Zealand, 1870–1940From EverandHistory, heritage, and colonialism: Historical consciousness, Britishness, and cultural identity in New Zealand, 1870–1940No ratings yet

- Bangerang Cultural CentreDocument11 pagesBangerang Cultural CentreFulya TorunNo ratings yet

- International Museums Should Repatriate Colonial ArtefactsDocument1 pageInternational Museums Should Repatriate Colonial ArtefactsDanny KensNo ratings yet

- HIST 106: Site Visit and AnalysisDocument4 pagesHIST 106: Site Visit and Analysisapi-404126817No ratings yet

- The colonisation of time: Ritual, routine and resistance in the British EmpireFrom EverandThe colonisation of time: Ritual, routine and resistance in the British EmpireNo ratings yet

- Art of The Pacific - IlandsDocument371 pagesArt of The Pacific - IlandsGigi MorarasNo ratings yet

- Brirish MuseumDocument10 pagesBrirish MuseumMelike KutluNo ratings yet

- Clarke, Philip 2003 - Where The Ancestors Walked - Aboriginal LandscapeDocument296 pagesClarke, Philip 2003 - Where The Ancestors Walked - Aboriginal Landscaperegvictor2kNo ratings yet

- 6min English MuseumsDocument4 pages6min English MuseumsbonbiaNo ratings yet

- 900-yr-old African coins in Australia may solve mysteryDocument14 pages900-yr-old African coins in Australia may solve mystery3FnQz8tgNo ratings yet

- Australia at the Venice Biennale: A Century of Contemporary ArtFrom EverandAustralia at the Venice Biennale: A Century of Contemporary ArtNo ratings yet

- The Cyrus Cilinder 07Document2 pagesThe Cyrus Cilinder 07baguenaraNo ratings yet

- Round Mounds and Monumentality in the British Neolithic and BeyondFrom EverandRound Mounds and Monumentality in the British Neolithic and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Neolithisation in Europe: Studies in honour of Andrew SherrattFrom EverandDynamics of Neolithisation in Europe: Studies in honour of Andrew SherrattAngelos HadjikoumisNo ratings yet

- SUBMISSION - Queensland Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Heritage Act 2003 - ReviewDocument7 pagesSUBMISSION - Queensland Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Heritage Act 2003 - ReviewLindsay HackettNo ratings yet

- British Day Presentation (1) - 1.keyDocument41 pagesBritish Day Presentation (1) - 1.keyNicholl HeathNo ratings yet

- NigerianMuseumandArtPreservation OnlineFirst6copiesDocument20 pagesNigerianMuseumandArtPreservation OnlineFirst6copiesTim RebuladoNo ratings yet

- The Unburnt Egg: More Stories of a Museum CuratorFrom EverandThe Unburnt Egg: More Stories of a Museum CuratorRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- MuseumsDocument7 pagesMuseumsMinh MinhNo ratings yet

- Easter Island - The Heritage and Its Conservation PDFDocument74 pagesEaster Island - The Heritage and Its Conservation PDFSilalahi TaburNo ratings yet

- Elizabeth Burns Coleman. Historical - Ironie, The Australian Aboriginal Art RevolutionDocument22 pagesElizabeth Burns Coleman. Historical - Ironie, The Australian Aboriginal Art RevolutionGeneviève SaumierNo ratings yet

- Extreme Collecting: Challenging Practices for 21st Century MuseumsFrom EverandExtreme Collecting: Challenging Practices for 21st Century MuseumsNo ratings yet

- Attenbrow 2010 PJFishing Roy Zo SocvolumeDocument20 pagesAttenbrow 2010 PJFishing Roy Zo SocvolumedeluxepowerNo ratings yet

- As Native Americans, We Are in A Constant State of Mourning'Document3 pagesAs Native Americans, We Are in A Constant State of Mourning'TrentonNo ratings yet

- "Jacky Jacky Was A Smart Young Fella": A Study of Art and Aboriginality in South East Australia 1900-1980Document69 pages"Jacky Jacky Was A Smart Young Fella": A Study of Art and Aboriginality in South East Australia 1900-1980aisha10092002No ratings yet

- Contributions of Open Air Museums in Preserving Heritage Buildings: Study of Open-Air Museums in South East EnglandDocument14 pagesContributions of Open Air Museums in Preserving Heritage Buildings: Study of Open-Air Museums in South East EnglandMUHAMAD WAAIZ MOHD RIJALNo ratings yet

- Ancient African Artefacts From The Benin Bronzes To The Zimbabwe Birds Sky HISTORY TV ChannelDocument1 pageAncient African Artefacts From The Benin Bronzes To The Zimbabwe Birds Sky HISTORY TV ChannelPhil MoenNo ratings yet

- Gunbim KakaduDocument4 pagesGunbim Kakaduapi-281947898No ratings yet

- Prophet at the Gate: Norman Murray Bell and the Quest for PeaceFrom EverandProphet at the Gate: Norman Murray Bell and the Quest for PeaceNo ratings yet

- The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural RestitutionFrom EverandThe Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural RestitutionRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Modified MuseumDocument41 pagesModified MuseumBandi KotreshNo ratings yet

- Human Remains Trade EthicsDocument20 pagesHuman Remains Trade EthicsAnwesha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Mapping Modernisms - Art, Indige - Elizabeth HarneyDocument459 pagesMapping Modernisms - Art, Indige - Elizabeth HarneyGerardo Daniel Jiménez100% (1)

- Australian Dreaming 40000 Years TextDocument311 pagesAustralian Dreaming 40000 Years TextMuzzaBeeNo ratings yet

- Making Histories in MuseumsDocument302 pagesMaking Histories in MuseumsCease LessNo ratings yet

- Speakers AnnouncedDocument5 pagesSpeakers Announcedapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Australia Music AwardsDocument2 pagesAustralia Music Awardsapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Mens ChoraleDocument3 pagesMens Choraleapi-238501268No ratings yet

- The 2013 Annual Awgie Awards WinnersDocument4 pagesThe 2013 Annual Awgie Awards Winnersapi-238501268No ratings yet

- John OlsenDocument3 pagesJohn Olsenapi-238501268No ratings yet

- World Class Aboriginal Art FestivalDocument3 pagesWorld Class Aboriginal Art Festivalapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Australia Council Congratulates National AboriginalDocument3 pagesAustralia Council Congratulates National Aboriginalapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Gold Coast Paintings Featured in French Art ExhibitionDocument2 pagesGold Coast Paintings Featured in French Art Exhibitionapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Literature Australia Loses Rarest VoiceDocument3 pagesLiterature Australia Loses Rarest Voiceapi-238501268No ratings yet

- 200 Years of Australian ArtDocument4 pages200 Years of Australian Artapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Dancesport ChampionshipDocument3 pagesDancesport Championshipapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Australian Youth EnsembleDocument1 pageAustralian Youth Ensembleapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Sydney Dance CompanyDocument4 pagesSydney Dance Companyapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Success at GeneeDocument4 pagesSuccess at Geneeapi-238501268No ratings yet

- Youth Dance FestivalDocument2 pagesYouth Dance Festivalapi-238501268No ratings yet

- HCIA-WLAN V2.0 Training Materials PDFDocument885 pagesHCIA-WLAN V2.0 Training Materials PDFLeonardo Vargas Peña100% (6)

- 20 Laws by Sabrina Alexis and Eric CharlesDocument58 pages20 Laws by Sabrina Alexis and Eric CharlesLin Xinhui75% (4)

- Lab Report FormatDocument2 pagesLab Report Formatapi-276658659No ratings yet

- Bhushan ReportDocument30 pagesBhushan Report40Neha PagariyaNo ratings yet

- Hac 1001 NotesDocument56 pagesHac 1001 NotesMarlin MerikanNo ratings yet

- AmulDocument4 pagesAmulR BNo ratings yet

- English Course SyllabusDocument3 pagesEnglish Course Syllabusalea rainNo ratings yet

- ICE Learned Event DubaiDocument32 pagesICE Learned Event DubaiengkjNo ratings yet

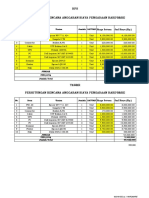

- HPS Perhitungan Rencana Anggaran Biaya Pengadaan Hardware: No. Item Uraian Jumlah SATUANDocument2 pagesHPS Perhitungan Rencana Anggaran Biaya Pengadaan Hardware: No. Item Uraian Jumlah SATUANYanto AstriNo ratings yet

- Underground Rock Music and Democratization in IndonesiaDocument6 pagesUnderground Rock Music and Democratization in IndonesiaAnonymous LyxcVoNo ratings yet

- Oilwell Fishing Operations Tools and TechniquesDocument126 pagesOilwell Fishing Operations Tools and Techniqueskevin100% (2)

- Climbing KnotsDocument40 pagesClimbing KnotsIvan Vitez100% (11)

- Once in his Orient: Le Corbusier and the intoxication of colourDocument4 pagesOnce in his Orient: Le Corbusier and the intoxication of coloursurajNo ratings yet

- Shilajit The Panacea For CancerDocument48 pagesShilajit The Panacea For Cancerliving63100% (1)

- Adjusted School Reading Program of Buneg EsDocument7 pagesAdjusted School Reading Program of Buneg EsGener Taña AntonioNo ratings yet

- E Purjee (New Technology For The Sugarcane Farmers)Document4 pagesE Purjee (New Technology For The Sugarcane Farmers)Mohammad Shaniaz IslamNo ratings yet

- Blood Culture & Sensitivity (2011734)Document11 pagesBlood Culture & Sensitivity (2011734)Najib AimanNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Networks Visual GuideDocument1 pageIntroduction to Networks Visual GuideWorldNo ratings yet

- IB Diploma Maths / Math / Mathematics IB DP HL, SL Portfolio TaskDocument1 pageIB Diploma Maths / Math / Mathematics IB DP HL, SL Portfolio TaskDerek Chan100% (1)

- Asia Competitiveness ForumDocument2 pagesAsia Competitiveness ForumRahul MittalNo ratings yet

- Master Your FinancesDocument15 pagesMaster Your FinancesBrendan GirdwoodNo ratings yet

- 001 Joseph Vs - BautistacxDocument2 pages001 Joseph Vs - BautistacxTelle MarieNo ratings yet

- Annexure 2 Form 72 (Scope) Annexure IDocument4 pagesAnnexure 2 Form 72 (Scope) Annexure IVaghasiyaBipinNo ratings yet

- Invoice Inv0006: Er. Mohamed Irshadh P MDocument1 pageInvoice Inv0006: Er. Mohamed Irshadh P Mmanoj100% (1)

- Hospitality Marketing Management PDFDocument642 pagesHospitality Marketing Management PDFMuhamad Armawaddin100% (6)

- Apple Inc.: Managing Global Supply Chain: Case AnalysisDocument9 pagesApple Inc.: Managing Global Supply Chain: Case AnalysisPrateek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Runner Cs-47 Link Rev-2 27-09-10Document29 pagesRunner Cs-47 Link Rev-2 27-09-10bocko74No ratings yet

- Waiver: FEU/A-NSTP-QSF.03 Rev. No.: 00 Effectivity Date: Aug. 10, 2017Document1 pageWaiver: FEU/A-NSTP-QSF.03 Rev. No.: 00 Effectivity Date: Aug. 10, 2017terenceNo ratings yet

- Jason Payne-James, Ian Wall, Peter Dean-Medicolegal Essentials in Healthcare (2004)Document284 pagesJason Payne-James, Ian Wall, Peter Dean-Medicolegal Essentials in Healthcare (2004)Abdalmonem Albaz100% (1)

- TOPIC 12 Soaps and DetergentsDocument14 pagesTOPIC 12 Soaps and DetergentsKaynine Kiko50% (2)