Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Atienza vs. COMELEC

Uploaded by

Judiel ParejaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Atienza vs. COMELEC

Uploaded by

Judiel ParejaCopyright:

Available Formats

JOSE L. ATIENZA vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS G.R. No. 188920, February 16, 2010 Facts: Franklin M.

Drilon (Drilon), as erstwhile president of the Liberal Party (LP), announced his partys withdrawal of support for the administration of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. But Jose L. Atienza, Jr. (Atienza), LP Chairman, and a number of party members denounced Drilons move, claiming that he made the announcement without consulting his party. Thereafter, Atienza hosted a party conference to supposedly discuss local autonomy and party matters but, when convened, the assembly proceeded to declare all positions in the LPs ruling body vacant and elected new officers, with Atienza as LP president. Drilon immediately filed a petition with the COMELEC to nullify the elections. He claimed that it was illegal considering that the partys electing bodies, the National Executive Council (NECO) and the National Political Council (NAPOLCO), were not properly convened. Drilon also claimed that under the amended LP Constitution, party officers were elected to a fixed three-year term that was yet to end on November 30, 2007. On the other hand, Atienza claimed that the majority of the LPs NECO and NAPOLCO attended the assembly. The election of new officers on that occasion could be likened to "people power," wherein the LP majority removed Drilon as president by direct action. Atienza also said that the amendments to the original LP Constitution, or the Salonga Constitution, giving LP officers a fixed three-year term, had not been properly ratified. Consequently, the term of Drilon and the other officers already ended. The COMELEC issued a resolution, partially granting respondent Drilons petition. It annulled the elections and ordered the holding of a new election under COMELEC supervision. It held that the election of Atienza and the others with him was invalid since the electing assembly did not convene in accordance with the Salonga Constitution. But, since the amendments to the Salonga Constitution had not been properly ratified, Drilons term may be deemed to have ended. Thus, he held the position of LP president in a holdover capacity until new officers were elected. Both sides of the dispute came to this Court to challenge the COMELEC rulings. A divided Court issued a resolution, granting Drilons petition and denying that of Atienza. The Court held, through the majority, that the COMELEC had jurisdiction over the intra-party leadership dispute; that the Salonga Constitution had been validly amended; and that, as a c onsequence, Drilons term as LP president was to end only on November 30, 2007. Subsequently, the LP held a NECO meeting to elect new party leaders before Drilons term expired. Fifty-nine NECO members out of the 87 who were supposedly qualified to vote attended. Before the election, however, several persons associated with Atienza sought to clarify their membership status and raised issues regarding the composition of the NECO. Eventually, that meeting installed Manuel A. Roxas II (Roxas) as the new LP president. Atienza and company filed a petition for mandatory and prohibitory injunction before the COMELEC against Roxas, Drilon and J.R. Nereus O. Acosta, the party secretary general. Atienza, et al. sought to enjoin Roxas from assuming the presidency of the LP, claiming that the NECO assembly which elected him was invalidly convened. They questioned the existence of a quorum and claimed that the NECO composition ought to have been based on a list appearing in the partys 60th Anniversary Souvenir Program. Both Atienza and Drilon adopted that list as common exhibit in the earlier cases and it showed that the NECO had 103 members. Atienza, et al. also complained that Atienza, the incumbent party chairman, was not invited to the NECO meeting and that some members, like Defensor, were given the status of "guests" during the meeting. Atienzas allies allegedly raised these issu es but Drilon arbitrarily thumbed them down and "railroaded" the proceedings. He suspended the meeting and moved it to another room, where Roxas was elected without notice to Atienzas allies. On the other hand, Roxas, et al. claimed that Roxas election as LP president faithfully complied with the provisions of the amended LP Constitution. The partys 60th Anniversary Souvenir Program could not be used for determining the NECO members because supervening events changed the bodys number and composition. Some NECO members had died, voluntarily resigned, or had gone on leave after accepting positions in the government. Others had lost their re-election bid or did not run in the May 2007 elections, making them ineligible to serve as NECO members. LP members who got elected to public office also became part of the NECO. Certain persons of national stature also became NECO members upon Drilons nomination, a privilege granted the LP president under the amended LP Constitution. In other words, the NECO membership was not fixed or static; it changed due to supervening circumstances. Roxas, et al. also claimed that the party deemed Atienza, Zaldivar-Perez, and Cast-Abayon resigned for holding the illegal election of LP officers. This was pursuant to a March 14, 2006 NAPOLCO

Page 1 of 3

resolution that NECO subsequently ratified. Meanwhile, certain NECO members, like Defensor, Valencia, and Suarez, forfeited their party membership when they ran under other political parties during the May 2007 elections. They were dropped from the roster of LP members. Thereafter, the COMELEC issued the assailed resolution denying Atienza, et al.s petition. As for the validity of Atienza, et al.s expulsion as LP members, the COMELEC observed that this was a membership issue that related to disciplinary action within the political party. The COMELEC treated it as an internal party matter that was beyond its jurisdiction to resolve. Without filing a motion for reconsideration of the COMELEC resolution, Atienza, et al. filed this petition for certiorari under Rule 65. Issues: 1. Whether or not the COMELEC gravely abused its discretion when it upheld the NECO membership that elected respondent Roxas as LP president; 2. Whether or not the COMELEC gravely abused its discretion when it resolved the issue concerning the validity of the NECO meeting without first resolving the issue concerning the expulsion of Atienza, et al. from the party; and 3. Whether or not Roxas, et al. violated Atienza, et al.s constitutional right to due process by the latters expulsion from the party. Ruling: One. Nothing in the Courts resolution in the earlier cases implies that the NECO membership should be pegged to the partys 60th Anniversary Souvenir Program. There would have been no basis for such a position. The amended LP Constitution did not intend the NECO membership to be permanent. The NECO was validly convened in accordance with the amended LP Constitution. Roxas, et al. explained in details how they arrived at the NECO composition for the purpose of electing the party leaders. The explanation is logical and consistent with party rules. Consequently, the COMELEC did not gravely abuse its discretion when it upheld the composition of the NECO that elected Roxas as LP president. Atienza claims that the Courts resolution in the earlier cases recognized his right as party chairman with a term, like Drilon, that would last up to November 30, 2007 and that, therefore, his ouster from that position violated the Courts resolution. But the Courts resolution in the earlier cases did not preclude the party from disciplining Atienza under the amended LP Constitution. The party could very well remove him or any officer for cause as it saw fit. Second. Atienza, et al. lament that the COMELEC selectively exercised its jurisdiction when it ruled on the composition of the NECO but refused to delve into the legality of their expulsion from the party. The two issues, they said, weigh heavily on the leadership controversy involved in the case. The previous rulings of the Court, they claim, categorically upheld the jurisdiction of the COMELEC over intraparty leadership disputes. But, as Roxas, et al. point out, the key issue in this case is not the validity of the expulsion of Atienza, et al. from the party, but the legitimacy of the NECO assembly that elected Roxas as LP president. Given the COMELECs finding as upheld by this Court that the member ship of the NECO in question complied with the LP Constitution, the resolution of the issue of whether or not the party validly expelled petitioners cannot affect the election of officers that the NECO held . Consequently, Atienza, et al. cannot claim that their expulsion from the party impacts on the party leadership issue or on the election of Roxas as president so that it was indispensable for the COMELEC to adjudicate such claim. Under the circumstances, the validity or invalidity of Atienza, et al.s ex pulsion was purely a membership issue that had to be settled within the party. It is an internal party matter over which the COMELEC has no jurisdiction. What is more, some of Atienzas allies raised objections before the NECO assembly regarding the status of members from their faction. Still, the NECO proceeded with the election, implying that its membership, whose composition has been upheld, voted out those objections. The COMELECs jurisdiction over intra-party disputes is limited. It does not have blanket authority to resolve any and all controversies involving political parties. Political parties are generally free to conduct their activities without interference from the state. The COMELEC may intervene in disputes internal to a party only when necessary to the discharge of its constitutional functions. The COMELECs jurisdiction over intra-party leadership disputes has already been settled by the Court. The Court ruled in Kalaw vs. Commission on Elections that the COMELECs powers and functions under Section 2, Article IX-C of the Constitution, "include the ascertainment of the identity of the political party and its legitimate officers responsible for its acts." The Court also

Page 2 of 3

declared in another case that the COMELECs power to register political par ties necessarily involved the determination of the persons who must act on its behalf. Thus, the COMELEC may resolve an intra-party leadership dispute, in a proper case brought before it, as an incident of its power to register political parties. The validity of Roxas election as LP president is a leadership issue that the COMELEC had to settle. Under the amended LP Constitution, the LP president is the issuing authority for certificates of nomination of party candidates for all national elective positions. It is also the LP president who can authorize other LP officers to issue certificates of nomination for candidates to local elective posts. In simple terms, it is the LP president who certifies the official standard bearer of the party. The law also grants a registered political party certain rights and privileges that will redound to the benefit of its official candidates. It imposes, too, legal obligations upon registered political parties that have to be carried out through their leaders. The resolution of the leadership issue is thus particularly significant in ensuring the peaceful and orderly conduct of the elections. Three. The requirements of administrative due process do not apply to the internal affairs of political parties. The due process standards set in Ang Tibay cover only administrative bodies created by the state and through which certain governmental acts or functions are performed. An administrative agency or instrumentality "contemplates an authority to which the state delegates governmental power for the performance of a state function." The constitutional limitations that generally apply to the exercise of the states powers thus, apply too, to administrative bodies. Although political parties play an important role in our democratic set-up as an intermediary between the state and its citizens, it is still a private organization, not a state instrument. The discipline of members by a political party does not involve the right to life, liberty or property within the meaning of the due process clause. An individual has no vested right, as against the state, to be accepted or to prevent his removal by a political party . The only rights, if any, that party members may have, in relation to other party members, correspond to those that may have been freely agreed upon among themselves through their charter, which is a contract among the party members. Members whose rights under their charter may have been violated have recourse to courts of law for the enforcement of those rights, but not as a due process issue against the government or any of its agencies. But even when recourse to courts of law may be made, courts will ordinarily not interfere in membership and disciplinary matters within a political party. A political party is free to conduct its internal affairs, pursuant to its constitutionally-protected right to free association. In Sinaca vs. Mula, the Court said that judicial restraint in internal party matters serves the public interest by allowing the political processes to operate without undue interference. It is also consistent with the state policy of allowing a free and open party system to evolve, according to the free choice of the people. To conclude, the COMELEC did not gravely abuse its discretion when it upheld Roxas ele ction as LP president but refused to rule on the validity of Atienza, et al.s expulsion from the party. While the question of party leadership has implications on the COMELECs performance of its functions under Section 2, Article IX-C of the Constitution, the same cannot be said of the issue pertaining to Atienza, et al.s expulsion from the LP. Such expulsion is for the moment an issue of party membership and discipline, in which the COMELEC cannot intervene, given the limited scope of its power over political parties.

Page 3 of 3

You might also like

- Atienza Vs COMELECDocument2 pagesAtienza Vs COMELECrodel_odzNo ratings yet

- Atienza Vs COMELECDocument7 pagesAtienza Vs COMELECdeonita g. sangcoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest-Social Justice Society Vs Dangerous Drugs BoardDocument3 pagesCase Digest-Social Justice Society Vs Dangerous Drugs BoardZandra Jane Del Rosario100% (2)

- CSC Vs Pilila Water District Case DigestDocument2 pagesCSC Vs Pilila Water District Case DigestEula100% (2)

- ABC Party List V ComelecDocument2 pagesABC Party List V ComeleckayelaurenteNo ratings yet

- Atong Paglaum Inc. Vs COMELEC G.R. No. 203766Document3 pagesAtong Paglaum Inc. Vs COMELEC G.R. No. 203766Rowell Ian Gana-an100% (3)

- Zarate Vs Aquino Case DigestDocument2 pagesZarate Vs Aquino Case DigestClaudine Ann ManaloNo ratings yet

- Santiago Vs Bautista, 32 SCRA 188 Case Digest (Administrative Law)Document3 pagesSantiago Vs Bautista, 32 SCRA 188 Case Digest (Administrative Law)AizaFerrerEbina83% (6)

- Paredes v. SandiganbayanDocument1 pageParedes v. SandiganbayanpapabolNo ratings yet

- Pamil v. Teleron (Digest)Document2 pagesPamil v. Teleron (Digest)ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Deloso v. DomingoDocument2 pagesDeloso v. DomingoCZARINA ANN CASTRONo ratings yet

- Bustamante Vs COADocument2 pagesBustamante Vs COAAnonymous 8SgE99100% (1)

- Parreno Vs CoaDocument1 pageParreno Vs CoaLiz LorenzoNo ratings yet

- Tobais vs. Abalos Case DigestDocument3 pagesTobais vs. Abalos Case DigestHoney IvyNo ratings yet

- Miller Vs PerezDocument2 pagesMiller Vs PerezAthena SantosNo ratings yet

- President's power to call out AFP upheldDocument2 pagesPresident's power to call out AFP upheldCin100% (1)

- CL1-Parliamentary Immunity Not AbsoluteDocument2 pagesCL1-Parliamentary Immunity Not AbsoluteBea CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- Villaluz V ZaldivarDocument1 pageVillaluz V ZaldivarAnonymous lokXJkc7l7No ratings yet

- Banat v. Comelec Case DigestDocument2 pagesBanat v. Comelec Case DigestPauline93% (29)

- Gsis Vs KapisananDocument2 pagesGsis Vs KapisananJoel G. AyonNo ratings yet

- Negros Oriental II Electric Cooperative v. Sangguniang PanlungsodDocument2 pagesNegros Oriental II Electric Cooperative v. Sangguniang Panlungsodcatrina lobatonNo ratings yet

- MEWAP Vs RomuloDocument1 pageMEWAP Vs RomuloJenna Garces100% (1)

- Jaworski Vs PagcorDocument2 pagesJaworski Vs PagcorJsa Gironella100% (1)

- Kilusang Mayo Uno Vs Director General NEDA DigestDocument1 pageKilusang Mayo Uno Vs Director General NEDA DigestJeongNo ratings yet

- Impartial Tribunal Rule in Paderanga v. AzuraDocument1 pageImpartial Tribunal Rule in Paderanga v. Azuraalma navarro escuzar100% (1)

- Gma Network v. ComelecDocument1 pageGma Network v. ComelecMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- COA Chair Term LimitsDocument3 pagesCOA Chair Term Limitskathrynmaydeveza80% (5)

- Digest - (5th Batch) Salonga vs. HermosoDocument33 pagesDigest - (5th Batch) Salonga vs. HermosoCarlo Troy AcelottNo ratings yet

- Neri VS Senate DigestDocument5 pagesNeri VS Senate DigestImee Atibula-Petilla100% (1)

- SWS v. COMELEC Restriction on Election Survey Publication Violates Freedom of SpeechDocument1 pageSWS v. COMELEC Restriction on Election Survey Publication Violates Freedom of SpeechJade Viguilla100% (2)

- G. 41. Standard Chartered Bank Vs Senate Committee On Banks, Financial Institution and CurrenciesDocument2 pagesG. 41. Standard Chartered Bank Vs Senate Committee On Banks, Financial Institution and CurrenciesJairus LacabaNo ratings yet

- Dimaporo Vs Mitra JR DigestDocument2 pagesDimaporo Vs Mitra JR DigestMarc Dave AlcardeNo ratings yet

- Pangcatan Vs MaghuyopDocument2 pagesPangcatan Vs MaghuyopAngelDelaCruz75% (4)

- Carino v. CHR DigestDocument3 pagesCarino v. CHR Digestkathrynmaydeveza100% (2)

- Laban NG Demokratikong Pilipino v. COMELECDocument1 pageLaban NG Demokratikong Pilipino v. COMELECAnonymous 5MiN6I78I0100% (1)

- Romero V EstradaDocument2 pagesRomero V Estradafranzadon100% (2)

- PGBI Vs Comelec DigestDocument2 pagesPGBI Vs Comelec DigestAna Adolfo80% (5)

- Gutierrez v House Committee on Impeachment BarDocument1 pageGutierrez v House Committee on Impeachment BarPeterNo ratings yet

- Macalintal Vs Comelec DigestDocument2 pagesMacalintal Vs Comelec DigestYeshua Tura0% (1)

- Municipal Board of Canvassers of Glan VDocument2 pagesMunicipal Board of Canvassers of Glan Vbablatin100% (2)

- 35 - Funa vs. ErmitaDocument1 page35 - Funa vs. ErmitanorbygeraldezNo ratings yet

- DANTE V. LIBAN, vs. RICHARD J. GORDON, G.R. No. 175352, July 15Document4 pagesDANTE V. LIBAN, vs. RICHARD J. GORDON, G.R. No. 175352, July 15Marianne Serrano100% (3)

- Kulayan V TanDocument3 pagesKulayan V TanKlauwie Densen KantalaNo ratings yet

- Ang Ladlad LGBT Party V Comelec DigestDocument2 pagesAng Ladlad LGBT Party V Comelec DigestAmado Peter Garbanzos80% (5)

- A) Negros Oriental II Electric Cooperative Vs Sanguniang Panlungsod of Dumaguete DigestDocument1 pageA) Negros Oriental II Electric Cooperative Vs Sanguniang Panlungsod of Dumaguete DigestSolomon Malinias Bugatan100% (1)

- OCA Vs ReyesDocument2 pagesOCA Vs ReyesTeff Quibod100% (3)

- Abbas V SET DigestDocument1 pageAbbas V SET DigestNiq Polido100% (2)

- Digest - Sabio v. GordonDocument2 pagesDigest - Sabio v. GordonMaria Anna M LegaspiNo ratings yet

- SSS Employees Association V SorianoDocument3 pagesSSS Employees Association V SorianoAlphonse Samson75% (4)

- Lansang V GarciaDocument6 pagesLansang V GarciaDanielleNo ratings yet

- COMELEC ORDER STRIKING DOWN DIOCESE TARPAULINSDocument2 pagesCOMELEC ORDER STRIKING DOWN DIOCESE TARPAULINSMan2x Salomon100% (4)

- Procedural Due Process Before Administrative BodiesDocument4 pagesProcedural Due Process Before Administrative BodiesFernando OrganoNo ratings yet

- Radiowealth Inc. V Agregado DigestDocument2 pagesRadiowealth Inc. V Agregado DigestAlthea M. Suerte100% (1)

- Comelec Resolution Requiring Free Newspaper Space Ruled UnconstitutionalDocument3 pagesComelec Resolution Requiring Free Newspaper Space Ruled UnconstitutionalFranzMordenoNo ratings yet

- PADMON Condominium vs. Ortigas Case DigestDocument2 pagesPADMON Condominium vs. Ortigas Case DigestKatrina PetracheNo ratings yet

- Trillanes IV vs. Pimentel, Sr.Document3 pagesTrillanes IV vs. Pimentel, Sr.akiko komodaNo ratings yet

- Ponente: Justice Abad: Atienza, Jr. Vs ComelecDocument10 pagesPonente: Justice Abad: Atienza, Jr. Vs ComelecValerie ItomNo ratings yet

- F1 Atienza JR V ComelecDocument3 pagesF1 Atienza JR V ComelecBeya Amaro100% (1)

- Atienza V RoxasDocument4 pagesAtienza V RoxasRamBrySigueNo ratings yet

- COMELEC jurisdiction over election disputesDocument45 pagesCOMELEC jurisdiction over election disputesJanice DulotanNo ratings yet

- Arguments (Ibale Case)Document2 pagesArguments (Ibale Case)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Arguments (Ibale Case)Document2 pagesArguments (Ibale Case)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- RA 9904 - Magna Carta For Homeowners AssociationsDocument20 pagesRA 9904 - Magna Carta For Homeowners AssociationsRic Salvador50% (2)

- Cases For Search and SeizureDocument1 pageCases For Search and SeizureJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- PrescriptionDocument1 pagePrescriptionJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Loss (Voter's Identification Card)Document2 pagesAffidavit of Loss (Voter's Identification Card)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Loss (Company ID-EE)Document1 pageAffidavit of Loss (Company ID-EE)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Special ExamDocument2 pagesSpecial ExamJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Final Term Paper - Title PageDocument1 pageFinal Term Paper - Title PageJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Cases For Search and SeizureDocument1 pageCases For Search and SeizureJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- DonationDocument3 pagesDonationJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Antique MarksDocument14 pagesJapanese Antique MarksJudiel Pareja50% (2)

- ArgumentsDocument11 pagesArgumentsJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Tax AmnestyDocument1 pageTax AmnestyJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Loss (Company ID-EE)Document1 pageAffidavit of Loss (Company ID-EE)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Case Scenarios (MCLE)Document23 pagesCase Scenarios (MCLE)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Inherent PowersDocument2 pagesInherent PowersJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Cases On Legislative DepartmentDocument1 pageCases On Legislative DepartmentJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Legal Opinion (Cockfighting)Document3 pagesLegal Opinion (Cockfighting)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Disini vs. Secretary of JusticeDocument25 pagesDisini vs. Secretary of JusticeJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit (Authority To Receive Salary-K)Document1 pageAffidavit (Authority To Receive Salary-K)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- 2016 Revised Rules On Small Claims - Sample FormsDocument33 pages2016 Revised Rules On Small Claims - Sample FormsEliEliNo ratings yet

- LETTER (Police Station)Document1 pageLETTER (Police Station)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit (Authority To Receive Salary-J)Document1 pageAffidavit (Authority To Receive Salary-J)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Philippines Coast Guard Law of 2009Document8 pagesPhilippines Coast Guard Law of 2009De'clair AirollesNo ratings yet

- IRR of RA 9295 2014 Amendments - Domestic Shipping Development ActDocument42 pagesIRR of RA 9295 2014 Amendments - Domestic Shipping Development ActIrene Balmes-LomibaoNo ratings yet

- Borovsky vs. Commissioner of ImmigrationDocument1 pageBorovsky vs. Commissioner of ImmigrationJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- People vs. SantosDocument1 pagePeople vs. SantosJudiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Action Plan (Denr)Document2 pagesAction Plan (Denr)Judiel ParejaNo ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument1 pageReaction PaperJudiel Pareja100% (1)

- AI technologies improve HR analysisDocument4 pagesAI technologies improve HR analysisAtif KhanNo ratings yet

- Grade 4 DLL English 4 q4 Week 7Document3 pagesGrade 4 DLL English 4 q4 Week 7Cristina Singsing100% (1)

- INFOSEM Final ReportDocument40 pagesINFOSEM Final ReportManasa BanothNo ratings yet

- Civil Appeal 144 of 2019Document12 pagesCivil Appeal 144 of 2019Destiny LearningNo ratings yet

- Communication Process Quiz AnswersDocument3 pagesCommunication Process Quiz AnswersAbigail CullaNo ratings yet

- PV LITERATURE ROUGHDocument11 pagesPV LITERATURE ROUGHraghudeepaNo ratings yet

- Soal Uts Clea 2022-2023Document2 pagesSoal Uts Clea 2022-2023estu kaniraNo ratings yet

- Ipw - Proposal To OrganizationDocument3 pagesIpw - Proposal To Organizationapi-346139339No ratings yet

- The Curse of MillhavenDocument2 pagesThe Curse of MillhavenstipemogwaiNo ratings yet

- Annales School Impact on Contemporary History WritingDocument11 pagesAnnales School Impact on Contemporary History Writingrongon86No ratings yet

- Fear of Allah-HW Assignment by TahiyaDocument10 pagesFear of Allah-HW Assignment by TahiyashafaqkaziNo ratings yet

- PROACTIVITYDocument8 pagesPROACTIVITYShikhaDabralNo ratings yet

- CBRC Let Ultimate Learning Guide Social ScienceDocument112 pagesCBRC Let Ultimate Learning Guide Social ScienceAigene Pineda100% (2)

- Panaya SetupGuideDocument17 pagesPanaya SetupGuidecjmilsteadNo ratings yet

- Taxation of RFCs and NFCs in PHDocument4 pagesTaxation of RFCs and NFCs in PHIris Grace Culata0% (1)

- 300 Signs and Symptoms of Celiac DiseaseDocument7 pages300 Signs and Symptoms of Celiac DiseaseIon Logofătu AlbertNo ratings yet

- Experiment No. 16 - Preparation & Standardization of Oxalic Acid DataDocument2 pagesExperiment No. 16 - Preparation & Standardization of Oxalic Acid Datapharmaebooks100% (2)

- SQL SELECT statement examples and explanationsDocument5 pagesSQL SELECT statement examples and explanationsChen ChaNo ratings yet

- Wicked Arrangement WickednessDocument8 pagesWicked Arrangement WickednessbenchafulNo ratings yet

- Islamic Capital Markets: The Role of Sukuk: Executive SummaryDocument4 pagesIslamic Capital Markets: The Role of Sukuk: Executive SummaryiisjafferNo ratings yet

- Eunoia Fit 'n Slim - Slimming Coffee (Meal Plan)Document2 pagesEunoia Fit 'n Slim - Slimming Coffee (Meal Plan)jbkmw4hmvmNo ratings yet

- Juvy Ciocon-Reer v. Juddge Lubao (DIGEST)Document1 pageJuvy Ciocon-Reer v. Juddge Lubao (DIGEST)Glory Grace Obenza-Nodado100% (1)

- Datos Practicos TIMKENDocument128 pagesDatos Practicos TIMKENneodymioNo ratings yet

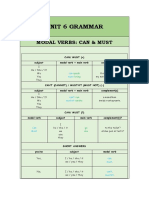

- Grammar - Unit 6Document3 pagesGrammar - Unit 6Fátima Castellano AlcedoNo ratings yet

- Iambic Pentameter in Poetry and Verse ExamplesDocument14 pagesIambic Pentameter in Poetry and Verse ExamplesIan Dante ArcangelesNo ratings yet

- D50311GC40 Les06Document37 pagesD50311GC40 Les06MuhammadSaadNo ratings yet

- Roy FloydDocument2 pagesRoy FloydDaniela Florina LucaNo ratings yet

- Rapid Modeling Solutions:: Introduction To Simulation and SimioDocument130 pagesRapid Modeling Solutions:: Introduction To Simulation and SimioCarlos TorresNo ratings yet

- Medical Missionary and The Final Crisis MainDocument256 pagesMedical Missionary and The Final Crisis MainHarold Wong100% (2)

- Advanced Research Methodology in EducationDocument18 pagesAdvanced Research Methodology in EducationReggie CruzNo ratings yet