Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TT FM Annotatingtext

Uploaded by

api-2679769420 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views2 pagesOriginal Title

tt fm annotatingtext

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views2 pagesTT FM Annotatingtext

Uploaded by

api-267976942Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

viii Toolkit Texts, Grades 23

Annotation as a Powerful Reading Tool

Recently we came across a document that Harvard College sends incoming freshmen to

prepare them for academic life. Interrogating Texts: Six Reading Habits to Develop in

Your First Year at Harvard describes reading behaviors that will help students get the

most out of text. The suggestions include previewing, annotating, summarizing and

analyzing, looking for patterns, contextualizing, and comparing and contrasting. All

contribute to thoughtful reading. Here we share what Harvard has to say about

annotating, because our Toolkit Texts offers a terrific opportunity for kids to merge their

thinking with the information through annotation.

Make all of your reading thinking intensive. . . .

Mark up the margins of your text with WORDS: ideas that occur to you, notes

about things that seem important to you, reminders of how issues in a text

may connect with class discussion or course themes. This kind of interaction

keeps you conscious of the REASON you are reading and the PURPOSES

your instructor has in mind. Later in the term, when you are reviewing for a

test or project, your marginalia will be useful memory triggers.

Develop your own symbol system: asterisk a key idea, for example, or use an

exclamation point for the surprising, absurd, bizarre. . . . Like your marginalia,

your hieroglyphs can help you reconstruct the important observations that you

made at an earlier time. And they will be indispensable when you return to a

text later in the term, in search of a passage or an idea for a topic, or while

preparing for an exam or project.

Get in the habit of hearing yourself ask questionsWhat does this mean?

Why is he or she drawing that conclusion? Why is the class reading this

text? etc. Write the questions down (in your margins, at the beginning or end

of the reading, in a notebook, or elsewhere). They are reminders of the

unfinished business you still have with a text: something to ask during class

discussion, or to come to terms with on your own, once youve had a chance

to digest the material further, or have done further reading.

http://hcl.harvard.edu/research/guides/lamont_handouts/interrogatingtexts.html

So we ask: why wait until our kids go off to college? We suggest kids read thoughtfully

and leave tracks of their thinking as early as elementary school. Obviously elementary

school kids cannot write in their books, but you can demonstrate how to use Post-its to

annotate texts as they read, or provide photocopies of these articles on which they can

write in the margins. The articles in this collection lend themselves to active reading

and responding.

When we design instruction, we peel back the layers of our own reading process to

decide what and how we need to teach with a particular text. So we have annotated an

article here to show how we would model our thinking for our students.

First, we read through the entire piece ourselves, authentically responding to it by

jotting our thinking in the margins or on Post-its when there is not enough room to

annotate on the page. To think critically about important issues and ideas, we need to

think and react in a thoughtful way as we read. We first consider our purpose for

reading. It might be to answer a question, to pick out important information, or simply

to learn more about a topic. We pay attention to our thinking, especially the strategies

we use and the reactions we have, coding the text accordingly. Then when we teach, we

think out loud as we read, demonstrating the strategies and language we use to

understand.

Introduction ix

As we read Wings in Water, we find ourselves visualizing the manta ray in its habitat.

The writer paints pictures with words that give us strong mental images that help us

better understand the topic. We code spots where we visualize with a V. We also find

ourselves asking questions and searching for answers to our questions. When we come

across information that answers our questions, we code those answers with an A.

Occasionally we underline words and phrases, and place our reactions in the margins. To

understand this article, we jot our thoughts in the margin and rely primarily on

visualizing and questioning.

Works Cited

Harvey, Stephanie, and Anne Goudvis. 2005. The Comprehension Toolkit. Language and Lessons for Active Literacy.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann/Firsthand.

Harvey, Stephanie, and Anne Goudvis. 2007. Strategies That Work: Teaching Comprehension for Understanding and

Engagement. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

President and Fellows of Harvard College. 2007. Interrogating Texts: Six Reading Habits to Develop in Your First Year at

Harvard. Available at: http://hcl.harvard.edu/research/guides/lamont_handouts/interrogatingtexts.html.

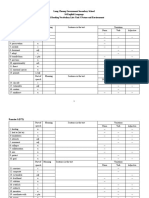

In addition to providing guided and independent

practice, the articles in these volumes may be used

to help students prepare for high-stakes tests. The

articles are quite similar to the selections that kids

encounter on many state tests. To maximize the

usefulness of these pieces when teaching the

genre of test reading, first study the format and

demands of your state test and develop practice

lessons that parallel the structure of that exam.

For a more detailed explanation of how to teach

test reading as a genre, please see our test reading

section on p. 74 in Extend and Investigate in The

Comprehension Toolkit.

Building strong readers is still the best test

preparation. Since prior knowledge is the most

powerful determinant in reading comprehension,

building background knowledge is ultimately the

most direct route to raising scores. When kids read

extensively across many topics and subject areas,

they will add to their store of knowledge, which is

one reason we urge our kids to read so much

nonfiction.

The Genre of Test Reading: Thoughtful Test Prep

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Etica Si Integritate AcademicaDocument242 pagesEtica Si Integritate AcademicaArhanghelul777No ratings yet

- Write Your Answers A, B, C or D in The Numbered Box (1 Point)Document70 pagesWrite Your Answers A, B, C or D in The Numbered Box (1 Point)A06-Nguyễn Yến NhiNo ratings yet

- MYLASTDUCHESSDocument6 pagesMYLASTDUCHESSHarvinPopatNo ratings yet

- Course Coverage Summary & Question Bank: Department of Electronics & Communication EngineeringDocument26 pagesCourse Coverage Summary & Question Bank: Department of Electronics & Communication EngineeringThe AnonymousNo ratings yet

- Humility in Prayer 2Document80 pagesHumility in Prayer 2Malik Saan BayramNo ratings yet

- Life.: Zarlino, Gioseffo (Gioseffe)Document10 pagesLife.: Zarlino, Gioseffo (Gioseffe)Jorge Pérez PérezNo ratings yet

- JavaFX CSS Reference GuideDocument25 pagesJavaFX CSS Reference GuideplysriNo ratings yet

- The University of Texas at Austin CS 372H Introduction To Operating Systems: Honors: Spring 2010 Final ExamDocument25 pagesThe University of Texas at Austin CS 372H Introduction To Operating Systems: Honors: Spring 2010 Final ExamDimitrios A. KarrasNo ratings yet

- CPAR Module 3Document21 pagesCPAR Module 3Liam BaxtonNo ratings yet

- Learn Spanish II at OSUDocument18 pagesLearn Spanish II at OSUGabriella WittbrodNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Vocab Worksheet (From Textbook)Document3 pagesUnit 3 Vocab Worksheet (From Textbook)clarikeiNo ratings yet

- Test Instructions: Audio File and Transcript Labels 01 Healthyeatinggroups - 08.01.19 - 500Pm - Group1Document4 pagesTest Instructions: Audio File and Transcript Labels 01 Healthyeatinggroups - 08.01.19 - 500Pm - Group1Adam ElmarouaniNo ratings yet

- Cqm1 Cqm1h ManualDocument75 pagesCqm1 Cqm1h ManualCicero MelloNo ratings yet

- Oral Com 1Document10 pagesOral Com 1Educ AcohNo ratings yet

- Sweet Goodmorning MessageDocument7 pagesSweet Goodmorning MessageKatheryn WinnickNo ratings yet

- A Literary Study of Odovan, An Urhobo Art FormDocument93 pagesA Literary Study of Odovan, An Urhobo Art Formaghoghookuneh75% (4)

- Load Top 100 Rows Excel File Big Data SQL Server SSISDocument7 pagesLoad Top 100 Rows Excel File Big Data SQL Server SSISKali RajNo ratings yet

- Completing Sentences Using Given WordsDocument4 pagesCompleting Sentences Using Given WordsTante DeviNo ratings yet

- Módulo+12+B1++Document17 pagesMódulo+12+B1++Brayan Alexander Gil SandovalNo ratings yet

- Notes Programming UpdatedDocument5 pagesNotes Programming UpdatedShifra Jane PiqueroNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 1 - What Do Seeds Need To Grow Group 1Document5 pagesLesson Plan 1 - What Do Seeds Need To Grow Group 1api-321143976No ratings yet

- Adjectives ending in ed or ing describing feelings and causesDocument1 pageAdjectives ending in ed or ing describing feelings and causesGuille RastilloNo ratings yet

- Actor Packets, Etc. - Dramaturgy - As You Like ItDocument13 pagesActor Packets, Etc. - Dramaturgy - As You Like Itclarahittel100% (2)

- Icp Output Question (With Ans) - 1Document23 pagesIcp Output Question (With Ans) - 1Smriti RoutNo ratings yet

- Kinder 2 3.2 Monthly Exam EnglishDocument22 pagesKinder 2 3.2 Monthly Exam Englishjoms GualbertoNo ratings yet

- Uss Matters and Discover Series BrochureDocument20 pagesUss Matters and Discover Series BrochureHihiNo ratings yet

- The Flirtation Dance of the Philippines: CariñosaDocument4 pagesThe Flirtation Dance of the Philippines: CariñosaGem Lam Sen50% (2)

- SMA IPIEMS SURABAYA - Modul Ajar Bhs Inggris TK LanjutDocument8 pagesSMA IPIEMS SURABAYA - Modul Ajar Bhs Inggris TK LanjutI Gde Rama Putra YudaNo ratings yet

- The Milkmaid and Her PailDocument2 pagesThe Milkmaid and Her Pailmiranda sanchezNo ratings yet

- Vdoc - Pub Glencoe Literature Reading With Purpose Course 1Document1,226 pagesVdoc - Pub Glencoe Literature Reading With Purpose Course 1NooneNo ratings yet