Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Landmark Response To Regal's Motion To Dismiss

Uploaded by

Benjamin FreedOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Landmark Response To Regal's Motion To Dismiss

Uploaded by

Benjamin FreedCopyright:

Available Formats

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 1 of 54

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

SILVER CINEMAS ACQUISITION CO. DBA

LANDMARK THEATRES,

Plaintiff,

v.

Civil Action No. 1:16-cv-123 (CRC)

ORAL ARGUMENT

REQUESTED

REGAL ENTERTAINMENT GROUP; REGAL

ENTERTAINMENT HOLDINGS, INC.; REGAL

ENTERTAINMENT HOLDINGS II, LLC; REGAL

CINEMAS CORPORATION; REGAL CINEMAS

HOLDINGS, INC.; REGAL CINEMAS, INC.;

REGAL CINEMAS II, LLC and REGAL GALLERY

PLACE LLC,

Defendants.

LANDMARKS MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES

IN OPPOSITION TO REGALS MOTION TO DISMISS

130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 2 of 54

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FACTUAL BACKGROUND AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY ................................................. 2

ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................................. 7

I.

MOTION TO DISMISS STANDARD ................................................................... 8

II.

THE COMPLAINT ADEQUATELY ALLEGES PER SE

ILLEGAL CIRCUIT DEALING ............................................................................ 9

III.

THE COMPLAINT ADEQUATELY ALLEGES NONCIRCUIT DEALING-BASED VIOLATIONS OF THE

SHERMAN ACT .................................................................................................. 13

A.

Regals Blanket Clearance Fails the Paramount

Substantial Competition Test .................................................................... 14

B.

The Complaint Adequately Alleges Sherman Act

Violations Under the Modern Rule of Reason .......................................... 18

C.

IV.

1.

The Complaint Alleges Direct Evidence of

Regals Market Power................................................................... 20

2.

The Complaint Alleges Circumstantial

Evidence of Regals Market Power .............................................. 22

3.

The Complaint Alleges Exclusionary

Conduct by Regal that Has Harmed

Competition and ConsumersNot Just

Landmark ...................................................................................... 30

4.

Regals Blanket Clearance Agreements

Have No Procompetitive Justification .......................................... 35

The Complaint Adequately Alleges Classic

Unlawful Clearance Agreements Between Regal

and the Film Distributors .......................................................................... 39

THE COMPLAINT ADEQUATELY ALLEGES

VIOLATIONS OF D.C. LAW.............................................................................. 42

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................. 43

130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 3 of 54

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

A.L.B. Theatre Corp. v. Loews, Inc.,

355 F.2d 495 (7th Cir. 1966) .............................................................................................33, 34

Am. Tobacco Co. v. United States,

328 U.S. 781 (1946) .................................................................................................................29

Apani Sw., Inc. v. Coca-Cola Enters., Inc.,

300 F.3d 620 (5th Cir. 2002) ...................................................................................................26

Arnett Physician Grp., P.C. v. Greater LaFayette Health Servs., Inc.,

382 F. Supp. 2d 1092 (N.D. Ind. 2005) ...................................................................................27

Babyage.com, Inc. v. Toys R Us, Inc.,

558 F. Supp. 2d 575 (E.D. Pa. 2008) .................................................................................20, 32

Banneker Ventures, LLC v. Graham,

798 F.3d 1119 (D.C. Cir. 2015) ...............................................................................................43

Baxley-DeLamar Monuments, Inc. v. Am. Cemetery Assn,

843 F.2d 1154 (8th Cir. 1988) .................................................................................................29

Belizan v. Hershon,

434 F.3d 579 (D.C. Cir. 2006) ...................................................................................................9

Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly,

550 U.S. 544 (2007) ......................................................................................................... passim

Broadcom Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc.,

501 F.3d 297 (3d Cir. 2007).....................................................................................................19

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States,

370 U.S. 294 (1962) ...........................................................................................................22, 25

Cheeks v. Fort Myer Constr. Corp.,

71 F. Supp. 3d 163 (D.D.C. 2014) ...........................................................................................40

Chi. Ridge Theatre Ltd. Pship v. M & R Amusement Corp.,

732 F. Supp. 1503 (N.D. Ill. 1990) ..........................................................................................17

Chi. Ridge Theatre Ltd. Pship v. M & R Amusement Corp.,

855 F.2d 465 (7th Cir. 1988) ...................................................................................................15

City of Moundridge v. Exxon Mobil Corp.,

250 F.R.D. 1 (D.D.C. 2008).....................................................................................................40

- ii 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 4 of 54

Cloverleaf Enters., Inc. v. Md. Thoroughbred, Horsemens Assn,

730 F. Supp. 2d 451 (D. Md. 2010) ...........................................................................................9

Cobb Theatres III, LLC v. AMC Entmt Holdings, Inc.,

101 F. Supp. 3d 1319 (N.D. Ga. 2015) ............................................................................ passim

Concord Assocs. L.P. v. Entmt Props. Trust,

817 F.3d 46 (2d Cir. 2016).......................................................................................................26

Cooper v. First Govt Mortg. & Invrs Corp.,

206 F. Supp. 2d 33 (D.D.C. 2002) ...........................................................................................12

E & L Consulting, Ltd. v. Doman Indus. Ltd.,

472 F.3d 23 (2d Cir. 2006).................................................................................................30, 31

E. Food Servs., Inc. v. Pontifical Catholic Univ. Servs. Assn, Inc.,

357 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2004) ........................................................................................................26

E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. v. Kolon Indus., Inc.,

637 F.3d 435 (4th Cir. 2011) ...................................................................................................23

Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Tech. Servs., Inc.,

504 U.S. 451 (1992) .................................................................................................................32

Elecs. Commcns Corp. v. Toshiba Am. Consumer Prods., Inc.,

129 F.3d 240 (2d Cir. 1997).....................................................................................................30

Flagship Theatres of Palm Desert, LLC v. Century Theatres, Inc.,

131 Cal. Rptr. 3d 519 (Cal. Ct. App. 2011) .........................................................................9, 13

FTC v. Ind. Fedn of Dentists,

476 U.S. 447 (1986) .................................................................................................................19

FTC v. Sysco Corp.,

113 F. Supp. 3d 1 (D.D.C. 2015) .......................................................................................23, 26

GTE New Media Servs., Inc. v. Ameritech Corp.,

21 F. Supp. 2d 27 (D.D.C. 1998) .........................................................................................8, 42

Halberstam v. Welch,

705 F.2d 472 (D.C. Cir. 1983) .................................................................................................39

Hosp. Bldg. Co. v. Trs. of Rex Hosp.,

425 U.S. 738 (1976) ...................................................................................................................9

IHS Dialysis Inc. v. Davita, Inc.,

2013 WL 1309737 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2013) .........................................................................24

- iii 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 5 of 54

Image Tech. Servs., Inc. v. Eastman Kodak Co.,

125 F.3d 1195 (9th Cir. 1997) .................................................................................................19

In re High-Tech Employee Antitrust Litig.,

856 F. Supp. 2d 1103 (N.D. Cal. 2012) .......................................................................10, 22, 23

In re Lithium Ion Batteries Antitrust Litig.,

2014 WL 4955377 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 2, 2014)............................................................................42

In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig.,

968 F. Supp. 2d 367 (D. Mass. 2013) ................................................................................19, 22

iPic-Gold Class Entmt, LLC v. Regal Entmt Grp.,

No. 2015-68745 (Tex. Dist. Ct. 234th Jan. 21, 2016)..............................................................35

Jung v. Assn of Am. Med. Colls.,

300 F. Supp. 2d 119 (D.D.C. 2004) .............................................................................12, 39, 40

Kramer v. Time Warner Inc.,

937 F.2d 767 (2d Cir. 1991).....................................................................................................12

Kreuzer v. Am. Acad. of Periodontology,

735 F.2d 1479 (D.C. Cir. 1984) ...............................................................................................14

L.A. Draper & Son v. Wheelabrator-Frye, Inc.,

735 F.2d 414 (11th Cir. 1984) .................................................................................................22

Leegin Creative Leather Prods., Inc. v. PSKS, Inc.,

551 U.S. 877 (2007) .....................................................................................................18, 31, 32

Little Rock Cardiology Clinic PA v. Baptist Health,

591 F.3d 591 (8th Cir. 2009) ...................................................................................................26

Loews, Inc. v. Cinema Amusements, Inc.,

210 F.2d 86 (10th Cir. 1954) ...................................................................................................39

Mathias v. Daily News, L.P.,

152 F. Supp. 2d 465 (S.D.N.Y. 2001)......................................................................................26

Mazanderan v. Indep. Taxi Owners Assn,

700 F. Supp. 588 (D.D.C. 1988) ..............................................................................................42

Monsanto Co. v. Spray-Rite Serv. Corp.,

465 U.S. 752 (1984) .................................................................................................................42

Movie 1 & 2 v. United Artists Commcns, Inc.,

909 F.2d 1245 (9th Cir. 1990) .................................................................................................34

- iv 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 6 of 54

Orbo Theatre Corp. v. Loews Inc.,

156 F. Supp. 770 (D.D.C. 1957) ..................................................................................33, 35, 37

Orson, Inc. v. Miramax Film Corp.,

79 F.3d 1358 (3d Cir. 1996).....................................................................................................37

Osborn v. Visa Inc.,

797 F.3d 1057 (D.C. Cir. 2015) ...............................................................................................39

Oxbow Carbon & Minerals LLC v. Union Pac. R.R. Co.,

81 F. Supp. 3d 1 (D.D.C. 2015) ....................................................................................... passim

Paddock Pubs., Inc. v. Chi. Tribune Co.,

103 F.3d 42 (7th Cir. 1996) .....................................................................................................37

Quad Cinema Corp. v. Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corp.,

1983 WL 1822 (S.D.N.Y. May 12, 1983) ....................................................................... passim

Ralph C. Wilson Indus., Inc. v. Am. Broad. Cos.,

598 F. Supp. 694 (N.D. Cal. 1984) ..........................................................................................37

Re/Max Intl v. Realty One, Inc.,

173 F.3d 995 (6th Cir. 1999) ...................................................................................................19

Reading Intl, Inc. v. Oaktree Capital Mgmt. LLC,

2007 WL 39301 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 8, 2007) ........................................................................ passim

Reading Intl, Inc. v. Oaktree Capital Mgmt. LLC,

317 F. Supp. 2d 301 (S.D.N.Y. 2003).............................................................................. passim

Rebel Oil Co. v. Atl. Richfield Co.,

51 F.3d 1421 (9th Cir. 1995) ...................................................................................................29

Republic Tobacco Co. v. N. Atl. Trading Co.,

381 F.3d 717 (7th Cir. 2004) ...................................................................................................31

S. Pac. Commcns Co. v. Am. Tel. & Tel. Co.,

556 F. Supp. 825 (D.D.C. 1982), affd, 740 F.2d 980 (D.C. Cir. 1984) ..................................29

S. Pac. Commcns Co. v. Am. Tel. & Tel. Co.,

740 F.2d 1011 (D.C. Cir. 1984) ...............................................................................................19

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States,

334 U.S. 110 (1948) ...........................................................................................................13, 41

Scott v. District of Columbia,

101 F.3d 748 (D.C. Cir. 1996) .................................................................................................18

-v130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 7 of 54

Seven Gables Corp. v. Sterling Recreation Org. Co.,

1987 WL 56622 (W.D. Wash. June 25, 1987).......................................................15, 33, 36, 41

Six W. Retail Acquisition, Inc. v. Sony Theatre Mgmt. Corp.,

2004 WL 691680 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2004) .....................................................................34, 35

Sky Angel U.S., LLC v. Natl Cable Satellite Corp.,

33 F. Supp. 3d 14 (D.D.C. 2014) .............................................................................................40

Sky Angel U.S., LLC v. Natl Cable Satellite Corp.,

947 F. Supp. 2d 88 (D.D.C. 2013) .....................................................................................26, 30

Spectrum Sports, Inc. v. McQuillan,

506 U.S. 447 (1993) .................................................................................................................14

Starlight Cinemas v. Regal Entmt Grp.,

2014 WL 7781018 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 23, 2014) ....................................................................40, 41

Syufy Enters. v. Am. Multicinema, Inc.,

793 F.2d 990 (9th Cir. 1986) .............................................................................................23, 30

T. Harris Young & Assocs., Inc. v. Marquette Elecs., Inc.,

931 F.2d 816 (11th Cir. 1991) .................................................................................................22

Tampa Elec. Co. v. Nashville Coal Co.,

365 U.S. 320 (1961) .................................................................................................................22

Theee Movies of Tarzana v. Pac. Theatres, Inc.,

828 F.2d 1395 (9th Cir. 1987) ...............................................................................34, 37, 38, 41

Theme Promotions, Inc. v. News Am. Mktg. FSI,

546 F.3d 991 (9th Cir. 2008) ...................................................................................................19

Times-Picayune Publg Co. v. United States,

345 U.S. 594 (1953) .................................................................................................................26

Todd v. Exxon Corp.,

275 F.3d 191 (2d Cir. 2001).....................................................................................................23

Toys R Us, Inc. v. FTC,

221 F.3d 928 (7th Cir. 2000) ...................................................................................................31

United States v. Apple Inc.,

952 F. Supp. 2d 638 (S.D.N.Y. 2013)......................................................................................42

United States v. Conn. Natl Bank,

418 U.S. 656 (1974) ...........................................................................................................23, 26

- vi 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 8 of 54

United States v. Griffith,

334 U.S. 100 (1948) .......................................................................................................9, 10, 12

United States v. Grinnell Corp.,

384 U.S. 563 (1966) .................................................................................................................35

United States v. Microsoft Corp.,

253 F.3d 34 (D.C. Cir. 2001) ........................................................................................... passim

United States v. Paramount Pictures,

334 U.S. 131 (1948) ......................................................................................................... passim

United States v. Paramount Pictures,

70 F. Supp. 53 (S.D.N.Y. 1946).................................................................................................9

United States v. Phila. Natl Bank,

374 U.S. 321 (1963) ...........................................................................................................23, 26

United States v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co.,

310 U.S. 150 (1940) .................................................................................................................10

United States v. Visa U.S.A., Inc.,

344 F.3d 229 (2d Cir. 2003).........................................................................................19, 21, 29

W. Duplicating, Inc. v. Riso Kagaku Corp.,

2000 WL 1780288 (E.D. Cal. Nov. 21, 2000) .........................................................................22

Wampler v. Sw. Bell Tel. Co.,

597 F.3d 741 (5th Cir. 2010) ...................................................................................................26

William Goldman Theatres v. Loews, Inc.,

150 F.2d 738 (3d Cir. 1945).....................................................................................................34

York v. McHugh,

698 F. Supp. 2d 101 (D.D.C. 2010) .........................................................................................12

STATUTES

15 U.S.C. 1 .......................................................................................................................... passim

15 U.S.C. 2 .......................................................................................................................... passim

D.C. Code 28-4502 .................................................................................................................6, 42

D.C. Code 28-4503 .................................................................................................................6, 42

RULES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(d)(3)....................................................................................................................18

- vii 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 9 of 54

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Earl W. Kintner, Federal Antitrust Law (2013) .............................................................................22

Phillip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law: An Analysis of Antitrust

Principles and Their Application (3d & 4th eds. 2011-2014) .................................................20

- viii 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 10 of 54

In October of 2015, Landmark Theatres, an independent film exhibition company,

introduced an upscale, innovative new theater concept in the heart of Washington, D.C. with the

opening of its Atlantic Plumbing theater. Landmarks six-screen theater offers an intimate and

upscale experience, with premium food and alcohol and oversized, plush leather seats.

Consumers who had long stopped going to the movies because of the long lines, dirty bathrooms,

harsh neon lighting, unpleasant crowds, and sold-out shows at Regals tired Gallery Place theater

in Chinatown would now have a choiceor so Landmark thought.

As soon as Landmark sought to license commercial films, it was uniformly told by film

distributors that Regal had requestedand they had grantedclearance over Landmarks

theater. That is, they had agreed to license virtually all of their top commercial filmsmovies

like Star Wars and The Hunger Gamesexclusively to Regals Gallery Place theater and not to

Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing theater. This is despite the fact that, for years prior, Regals

Gallery Place had played films day and date withi.e., had not requested clearance overan

even closer theater in Union Station before that theater closed and left Regal with a monopoly in

the relevant market. As a result of Regals blanket clearance over Landmarks Atlantic

Plumbing, Landmark has largely been licensed the leftovers and has been forced to fill its

screens with films few people want to see. Moviegoers who want to watch the popular, widerelease films on the big screen are forced to see them at Regals Gallery Place or not at all. They

have been deprived of the higher quality and lower prices that Landmark sought to bring to the

District with its innovative new offering.

There is no procompetitive justification for the clearance agreements Regal has entered

into with distributors. Regal argues that it is in the economic interests of distributors to employ a

single exhibitor in the core of Washington, D.C. and that Landmarks and Regals theaters are

130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 11 of 54

simply competing for single-exhibitor status. But the economics and realities of modern film

distribution and history of this film zonealleged in the complaintsuggest just the opposite.

Today clearances impair, rather than serve, competition among commercial film

distributors. Specifically, clearance agreements do not, as they did during the 1940s and 1950s,

legitimately protect a local exhibitor from free-riding by competitors on an exhibitors

investment in promoting a distributors film: now distributors, not exhibitors, fund promotion.

Nor do clearances promote interbrand competition at the expense of intrabrand competition

or prevent audience splitting: in todays digital age, the costs of distributing films to multiple

theaters is negligible, and interbrand competitionand a distributors own independent

interestsare served by exhibition in as many theaters as possible. In the core of the District, as

elsewhere, clearances serve only the economic interests of an exhibitor large enough to force

distributors to agree to them. Absent Regals demand for preferential treatment and exclusivity,

the distributors would be free to (and would) license their wide-release, commercial films to both

the Gallery Place and Atlantic Plumbing theaters for day-and-date play to maximize their box

office grosses in the zone and reach the widest audience possible.

The only purpose Regals blanket clearance serves is to protect its old, worn-out, lowquality, high-priced theater from competition. Its effects are to stifle innovation, lower quality,

increase prices, run Landmarks theater out of business, and deprive consumers in the core of the

District of the choice of where to see a movie. Regals blanket clearance is anticompetitive and

illegal under the federal and D.C. antitrust and tortious interference laws. Its motion to dismiss

Landmarks complaint should be denied.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY

Regal is the largest movie theater circuit in the United States, with approximately 575

theaters nationwide and 24 theaters in the greater Washington, D.C. area alone. Amended

-2130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 12 of 54

Complaint (ECF No. 12) (Compl.) 16. Since 2004, it has operated the Regal Gallery Place

Stadium 14, a 14-screen, 3,350-seat theater in the heart of densely-populated downtown

Washington, D.C.s Gallery Place/Chinatown district. Id. 39, 44, 52. The Gallery Place was

built over a decade ago and offers a substandard moviegoing experience to patrons: long ticket

and concession lines, large, loud, and unpleasant crowds . . . , a virtually constant police presence,

sold-out shows, exorbitantly priced concessions, bag searches, dirty bathrooms, and standard

(non-plush/oversized) seating. Id. 40.

Seeking to expand the market for moviegoing in the core of Washington, D.C. (District

Core) by offering a substantially different and higher-quality experience, in October of 2015,

Landmark opened its six-screen, 344-seat Atlantic Plumbing theater in the Shaw/Howard

University neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Id. 41. In addition to classic and alternative

concessions, Atlantic Plumbing offers a full bar with premium food and alcoholic beverages,

including specialty cocktails, a wide variety of beer and wine, and unique, upscale food options

such as mini crab cakes and organic crispy chickpeas. Id. 42. Food and drinks purchased in the

bar can be taken into any auditorium to enjoy while watching a movie. Id. The theater also offers

oversized, plush leather seats, advance reserved seating, and automated ticketing kiosks. Id.

Ticket prices are up to 30 percent lower than at Regals Gallery Place. Id. 43.

As a first-run, commercial film theater, Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing sought to license

mainstream films like Star Wars and The Hunger Games from the major film distributors. Id.

66, 68. Landmark expected that distributors would license their wide releases to Landmarks

and Regals theaters day and datethat is, for exhibition on the same dates. This expectation

was based on the fact that distributors had, for years before AMCs and then Phoenix Theatres

Union Station 9 closed in 2009, licensed such films to that theater for day-and-date play with

-3130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 13 of 54

Regals Gallery Place, despite these theaters being only one mile away from each other and

operating substantially similar theaters. Id. 63-65, 82. In addition, Regals Gallery Place sells

out during prime showtimes, and Landmark expected to draw patrons back to the movies with a

substantially different experience. Id. 82-83. As such, there was and remains substantial

unmet demand for another theater showing mainstream films in the population-dense heart of

Washington, D.C. Id. 44, 52, 82-83. Indeed, distributors would maximize their films grossing

potential in this zoneas they used to do before the Union Station 9 closedby licensing films

for day-and-date play, a practice that has become common in the commercial film industry. Id.

65, 73, 82.

Nevertheless, when Landmark contacted each of the major film distributors in an effort to

license their commercial films for exhibition at its Atlantic Plumbing theater, it was told

uniformly that Regal had requested a blanket clearance over Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing

theater. Id. 66. In other words, Regal had requested that the film distributors agree to license

their films exclusively to Regals Gallery Place and not to license them to Landmarks Atlantic

Plumbing theater for the entirety of each films first theatrical run (which today is the entirety of

a films theatrical exhibition life, after which it is released on video on demand). Id. 24-25.

Furthermore, Regal threatened to retaliate against any distributor that nevertheless licensed any

commercial film to Landmark: Regal would refuse to play the film at its Gallery Place theater

and reserved the right to disadvantage that distributors films prospects at any of its 575 theaters

across the country. Id. 67.

In response, the film distributors agreed to grant Regals request for clearance: they

agreed to license their highest-grossing films exclusively to Regals Gallery Place theater and not

to even offer to license those films to Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing theater. Id. 69. For

-4130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 14 of 54

example, when Landmark sought to negotiate a license to exhibit Disneys mega-blockbuster

Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Disney informed Landmark that it had already agreed to license

the film exclusively to Regals Gallery Place and not to license the film to Landmark under any

terms. Id. 68-69. The same occurred with respect to Lionsgates blockbuster The Hunger

Games: Mockingjay, Part 2, Sonys blockbuster Spectre, Warner Bros. Our Brand Is Crisis, and

The Weinstein Companys Burnt. Id. Landmark was forced to fill its screens with substantially

lower-grossing, less desirable films and specialty or art films that are not an adequate substitute

for the commercial films licensed to the Gallery Place. Id. 71, 86-87. As a result, the Atlantic

Plumbing theater was unable to serve the patrons it could have attracted had the distributors not

agreed with Regal to license their in-demand movies exclusively to Regals Gallery Place, and it

is threatened with going out of business if this conduct continues. Id. 74, 79, 88.

Regals blanket clearance has crippled competition in the District Core. Landmarks

Atlantic Plumbing theater offers a higher-quality, more innovative, and lower-priced experience

than Regals Gallery Place, but its efforts to compete with Regal on the merits with these

offerings have been neutralized by its inability to access its most essential inputwide-release

commercial films. Id. 88-89. As a result, consumers who prefer Landmarks theater are forced

to see their first-choice film at Regals theater and suffer a lower-quality, higher-priced

moviegoing experienceor, in the case of sold-out shows at the Gallery Place, not to see their

first-choice film at all. Id. 75-77. If the distributors continue to adhere to Regals demands,

Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing theater will be forced to close its doors, resulting in even less

choice and output in the relevant market. Id. 88.

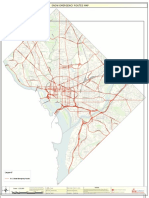

The relevant antitrust markets in which to analyze the anticompetitive effects of Regals

conduct are the markets to license and exhibit films in the District Corea densely populated

-5130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 15 of 54

area roughly bounded to the south by the National Mall, to the east by North Capitol Street, and

to the northwest by Rock Creek/Rock Creek Park. Id. 44. As the complaint alleges, consumers

in the District Core generally do not travel outside this area to attend a theatrical film exhibition,

and vice versa; given a small but substantial, nontransitory increase in the prices charged by

commercial film exhibitors in the District Core, District Core consumers would not travel farther

afield to avoid the price increase. Id. 46, 48. This is due to a variety of fact-intensive market

realities: high population density, heavy traffic congestion, unfamiliarity with areas outside the

District Core, the sheer distance of more distant theaters, the inconvenience and expense of

traveling outside the zone, and the inaccessibility of theaters outside the District Core by Metro,

on which most District Core consumers depend. Id. 47, 49-52. There are high barriers to entry

into this market, and Regal controls over 90% of it. Id. 56-58.

In January 2016, Landmark filed a complaint against Regal seeking relief under the

federal antitrust and D.C. antitrust and tortious interference laws from Regals anticompetitive

conduct and agreements. ECF No. 1.1 Landmark alleges five distinct causes of action: circuit

dealing in violation of Sherman Act Sections 1 and 2 and D.C. Code Sections 28-4502 and 284503 (Count I); contracts in restraint of trade in violation of Sherman Act Section 1 and D.C.

Code Section 28-4502 (Count II); monopolization (Count III) and attempted monopolization

(Count IV) in violation of Sherman Act Section 2 and D.C. Code Section 28-4503; and tortious

interference with business relations (Count V). Compl. 93-131. Regal has moved to dismiss

Landmarks complaint. ECF No. 16.

Landmark slightly amended its complaint as of right in February 2016. ECF No. 12.

-6130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 16 of 54

ARGUMENT

Because Landmarks complaint alleges in sufficient detail plausible antitrust claims under

federal and D.C. law, Regals motion should be denied.

First, Landmark alleges that Regal has engaged in per se illegal circuit dealinga

distinct violation of the antitrust laws arising from the leveraging of Regals circuit power to

coerce film distributors into granting Regal preferential film licensing treatment and excluding

Landmark. Regals arguments for dismissal of Landmarks circuit dealing claim ignore the

complaints allegations and misconstrue the governing case law.

Secondand regardless of whether the complaint plausibly alleges the distinct circuit

dealing claimRegals clearance is unreasonable under United States v. Paramount Pictures,

334 U.S. 131 (1948), and its progeny, without the need to evaluate whether Landmark has

alleged a plausible relevant antitrust market or Regals power in that market. That is because

Landmarks and Regals District Core theaters are not in substantial competition. Rather,

Landmarks theater largely appeals to a different audience and offers a substantially different

moviegoing experience.

Third, Regals conduct is anticompetitive under the modern rule of reason, which

requires proof of Regals market power and harm to competition resulting from Regals

anticompetitive or exclusionary conduct. Here, the precise delineation of a relevant market is not

necessary to establish an antitrust violation because Landmark has alleged direct evidence of

Regals market power. Landmarks complaint also alleges specific facts regarding consumer

preferences and practices and market realities that render the District Core a relevant antitrust

market and support a plausible inference of Regals ability to exercise market power in that

market.

-7130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 17 of 54

Landmark also alleges classic exclusionary conduct that has harmed competition. Based

on its false assumption that distributors want to contract with a single exhibitor in the District

Core, Regal speculates that distributors have decided not to license films to Landmark because

Landmark has not made sufficiently attractive offers (Motion 3) to win single-exhibitor status.

Regals arguments (a) ignore both the history of film-licensing in this zone and the economics of

modern commercial film distributionunder which the more theaters that show a distributors

film, the better(b) contradict the allegations in the complaint, and (c) assume the outcome of a

fact-intensive inquiry that is for the jurynot this Court on a motion to dismissto resolve.

Landmark has also plausibly alleged that Regals conduct was not merely unilateral.

Contrary to Regals contention, clearances like those at issue here have been understood in the

case law as Section 1 agreements for decades, and for good reason: implicit (if not explicit) in

every license that a distributor grants to Regals Gallery Place is the distributors agreement not

to license that same film for day-and-date play to Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing theater.

Furthermore, Landmark alleges specific facts supporting the inference that the exclusive licenses

at issue here are coerced agreementsnot just unilateral responses to a unilateral announcement.

Finally, because Regals arguments for dismissing Landmarks D.C. law claims are

derivative of its failing arguments for dismissal of Landmarks Sherman Act claims, the D.C.

law claims survive as well. Regals motion should be denied in its entirety.

I.

MOTION TO DISMISS STANDARD

In analyzing a motion to dismiss, the court must accept the allegations in the complaint

as true and construe them in light most favorable to the plaintiff. . . . The complaint must be

liberally construed in the plaintiffs favor, giving deference to inferences derived from the factual

allegations. GTE New Media Servs., Inc. v. Ameritech Corp., 21 F. Supp. 2d 27, 40 (D.D.C.

1998); see Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 555-56 (2007). [A] plaintiff need only

-8130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 18 of 54

make sufficient allegations of fact to raise a reasonable expectation that discovery will reveal

evidence of [the alleged violation]. Accordingly, in antitrust cases, summary procedures should

be used sparingly in complex antitrust litigation where motive and intent play leading roles and

dismissals prior to giving the plaintiff ample opportunity for discovery should be granted very

sparingly. Cloverleaf Enters., Inc. v. Md. Thoroughbred, Horsemens Assn, 730 F. Supp. 2d

451, 460 (D. Md. 2010) (quoting Twombly, 550 U.S. at 556; Hosp. Bldg. Co. v. Trs. of Rex Hosp.,

425 U.S. 738, 746 (1976)) (citation omitted). Even if it is extremely unlikely that a plaintiff will

recover, a complaint may nevertheless survive a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim,

and a court reviewing such a motion should bear in mind that it is testing the sufficiency of the

complaint and not the merits of the case. Cobb Theatres III, LLC v. AMC Entmt Holdings, Inc.,

101 F. Supp. 3d 1319, 1329 (N.D. Ga. 2015).2

II.

THE COMPLAINT ADEQUATELY ALLEGES PER SE ILLEGAL CIRCUIT

DEALING

As Regal concedes (Motion 2), circuit dealing is the licensing of film on other than a

theatre-by-theatre, film-by-film basis. See Paramount, 334 U.S. at 154; United States v.

Paramount Pictures, 70 F. Supp. 53, 74 (S.D.N.Y. 1946); Flagship Theatres of Palm Desert,

LLC v. Century Theatres, Inc., 131 Cal. Rptr. 3d 519, 524 (Cal. Ct. App. 2011) (reciting the

long-standing antitrust law requirement that films be licensed on a theater by theater, film by

film basis). An exhibitor engages in unlawful circuit dealing when it uses its strategic position

gained by having a monopoly of theatres in any one town to acquire exclusive privileges in a

city where he has competitors. United States v. Griffith, 334 U.S. 100, 107 (1948); see

Were the Court to grant Regals motion, Landmark respectfully requests leave to amend

to cure any deficiencies. See Belizan v. Hershon, 434 F.3d 579, 583 (D.C. Cir. 2006)

([D]ismissal with prejudice is warranted only when a trial court determines that the allegation of

other facts consistent with the challenged pleading could not possibly cure the deficiency.)

(emphasis and quotation marks omitted).

-9130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 19 of 54

Paramount, 334 U.S. at 154-55. Such conduct is a misuse of monopoly power under the

Sherman Act because [t]he consequence of such [conduct] is that films are licensed on a noncompetitive basis in what would otherwise be competitive situations. Griffith, 334 U.S. at 108

(exhibitor may not use the power it derives from its large circuit to stifle competition by

denying competitors less favorably situated access to the market); see Paramount, 334 U.S. at

154 (unlawful to eliminate the opportunity for the small competitor to obtain the choice first

runs, and put a premium on the size of the circuit).

[C]ircuit dealing [is] considered [a] per se violation[] of the Sherman Act. Cobb

Theatres, 101 F. Supp. 3d at 1343; Reading Intl, Inc. v. Oaktree Capital Mgmt. LLC (Reading

II), 2007 WL 39301, at *7 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 8, 2007). As Regal concedes, under the per se rule,

the plaintiff need not make any showing of market power or [anti]competitive effects. Motion

11 n.3; see United States v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co., 310 U.S. 150, 224 n.59 (1940).3

Landmark adequately alleges circuit dealing here. First, it alleges that Regal derives

substantial power over distributors from its status as the largest exhibitor circuit in the United

States, its numerous theaters in closed towns across the country where it is the only outlet for

distributors films, and its dominance in the greater Washington, D.C. area. Compl. 16.

Second, Landmark alleges that Regal demanded that distributors deny[] [its] competitor[]

[Landmark] less favorably situated access to the market, Griffith, 334 U.S. at 108, and

eliminate the opportunity for the small competitor [Landmark] to obtain the choice first runs,

3

Regal does not appear to dispute that circuit dealing is per se illegal under Paramount

and its progeny (Motion 11 n.3). Rather, it unremarkably points out (id.) that contracts in

restraint of trade and monopolization in the absence of circuit dealing are evaluated under the

rule of reason. To the extent Regal is contending that the per se rule does not apply, the Court

need not engage in a market analysis until the Court decides whether to apply a per se or rule of

reason analysis, and that decision is more appropriate on a motion for summary judgment. In

re High-Tech Employee Antitrust Litig., 856 F. Supp. 2d 1103, 1122-23 (N.D. Cal. 2012). It is

sufficient at this stage that Landmark has pled a per se claim. See id.

- 10 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 20 of 54

Paramount, 334 U.S. at 154, by licensing their films exclusively to Regals Gallery Place theater

and not to Landmark. Compl. 67. Third, Landmark alleges that Regal backed this demand to

deprive Landmark of the inputs it needs to compete with the threat that Regal could and would

disadvantage distributors films across Regals circuitincluding in its closed towns and its

numerous theaters throughout Washington, D.C.if the distributors did not comply. Id.; see id.

62. The distributors, fully cognizant of Regals ability to deprive them of substantial grosses on

their films across the country, bowed to Regals demand and, contrary to their own economic

interests, agreed not to license their choice first runs to Landmark. Id. 69, 71-72.4

Ignoring these allegations, Regal argues (Motion 8) that the complaint fails to allege that

Regal threatened to use its national circuit to deny the Atlantic Plumbing a single film. That is

simply not true. Landmark specifically alleges that Regals demand for a blanket clearance over

all films in favor of its Gallery Place theater included the message that [i]f you license a

commercial film to Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing theater, Regal can and will use its monopoly

power in the District Core, its dominance in the greater D.C. DMA, and its national circuit

power, to retaliate against you, including by reserving the right to disadvantage your films

prospects at any of Regals 575 theaters across the country. Compl. 67; see, e.g., Cobb

Theatres, 101 F. Supp. 3d at 1343 (denying motion to dismiss circuit dealing claim where

demand for blanket clearance allegedly operated as a demand that those distributors grant

[defendant] preferential treatment or, alternatively, risk being denied the grossing potential of

4

The complaint also quotes Regals annual report, in which Regal states that the size of

our theatre circuit is a significant competitive advantage for negotiating attractive national

contracts. Compl. 61; see Motion 10. Landmark did not misquote this statement (Motion

10). It quoted the excerpt, ending with negotiating, and indicated as much with a closequotation mark. Compl. 61. It then accurately paraphrased negotiating attractive national

contracts as negotiating with suppliers, including distributors. Id. Regals admission that its

size gives it an advantage in negotiating national contracts is at least circumstantial evidence that

Regal has power over its suppliers, including distributors.

- 11 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 21 of 54

[defendants competing] theater[] and, implicitly, some or all of the theaters in its entire circuit)

(quoting complaint). A dominant exhibitor need not be [so] crass as to make[] [an explicit]

threat to withhold the business of his closed or monopoly towns unless the distributors give him

the exclusive film rights in the towns where he has competitors to be held to have engaged in

circuit dealing. Griffith, 334 U.S. at 108; see Cobb Theatres, 101 F. Supp. 3d at 1344 (same).

The complaint alleges that Regal has consciously not licensed films on a theater by

theater, film by film basis (Motion 9), has demanded a blanket clearance in the District Core

covering all films from all distributorsand has backed that demand by the power of its circuit.

That is circuit dealing, and it violates the Sherman Act. Without the benefit of discovery, it is

difficult to imagine what additional facts (Motion 8) Landmark could possibly have alleged.5

Next, Regal argues that Landmark has not ruled out the possibility of the distributors

unilateral conduct (Motion 9). But at the Rule 12 dismissal stage, the plaintiff is not required to

eliminate the possibility of independent action . . . even if defendants allegations are also

plausible. Oxbow Carbon & Minerals LLC v. Union Pac. R.R. Co., 81 F. Supp. 3d 1, 13 & n.9

(D.D.C. 2015). Rather, the complaint need allege only plausible grounds to infer liability.

Twombly, 550 U.S. at 556. Regals argument is appropriate for the summary judgment (not Rule

12) stage. See Jung v. Assn of Am. Med. Colls., 300 F. Supp. 2d 119, 158-59 (D.D.C. 2004).

5

Regal cites legalese in its annual report to the effect that it supposedly licenses films on a

film-by-film and theatre-by-theatre basis (Motion 10). The Court may not consider this

statement because Regals annual report is not central to Landmarks complaint. Cooper v.

First Govt Mortg. & Invrs Corp., 206 F. Supp. 2d 33, 36 (D.D.C. 2002). At most, the Court can

take judicial notice of the unremarkable and wholly irrelevant fact that Regal self-servingly made

this statement, but not for the truth of the matter asserted. See Kramer v. Time Warner Inc., 937

F.2d 767, 774 (2d Cir. 1991). Regals annual report also admits that the size of our theatre

circuit is a significant competitive advantage for negotiating attractive national contracts,

Motion 10, suggesting negotiation on other than a film-by-film and theater-by-theater basis. At

most, these statements create a genuine dispute of fact as to whether Regal does, in fact, engage

in film-by-film, theater-by-theater licensing, which cannot be resolved at this stage. See York v.

McHugh, 698 F. Supp. 2d 101, 107 (D.D.C. 2010).

- 12 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 22 of 54

Regals belief that the complaints allegations support an alternative explanation for Regals

conduct does not contradict[] or undermine[] (Motion 9) Landmarks plausible claims.

Finally, Regal implies that a circuit dealing claim requires a showing that the defendant

threatened to forego playing a distributors films at all of [its] theatres nationwide and argues

that such a suggestion that Regal did so here makes no sense (id. at 11). But [n]othing in

the discussion in any of th[e] [Supreme Court circuit dealing] cases suggests that prohibited

circuit dealing is limited to agreements that cover all of the theaters in a circuit. Rather, they

suggest that it is not so limited. Flagship, 131 Cal. Rptr. 3d at 533 (rejecting same

misconstruction of case law that Regal makes here). By Regals logic, no circuit dealing claim

could ever be plausible because it would never make sense for a dominant exhibitor to

threaten to use its large buying power and combin[e] its closed and open towns to force

distributors not to deal with small exhibitors in discrete local markets. Schine Chain Theatres v.

United States, 334 U.S. 110, 115 (1948). Such conduct not only is plausible; it has actually

occurred and led to the creation of an entire body of Supreme Court case law outlawing it.

III.

THE COMPLAINT ADEQUATELY ALLEGES NON-CIRCUIT DEALINGBASED VIOLATIONS OF THE SHERMAN ACT

Contrary to Regals false refrain (Motion 2, 7, 12), Landmarks four distinct antitrust

claims do not all depend on the theory that Regal has engaged in circuit dealing. Only one of

its claimsthe circuit dealing claim (Count I)does. While Count I does in fact properly allege

a plausible circuit dealing claim under well-established precedents, Counts II, III, and IV are

non-circuit dealing claims that Regal has entered into contracts in restraint of trade and has

monopolized and attempted to monopolize the markets for film licensing and exhibition in the

District Core. Unlike the circuit dealing claim, these claims do not require Landmark to establish

that Regal has engaged in non-film-by-film or non-theater-by-theater film licensing, or leveraged

- 13 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 23 of 54

its power outside of the District Core to gain an unfair advantage in it. Rather, they require only a

showing of unreasonableness and, in the case of Count II, some form of joint action [that]

satisf[ies] the contracts, combinations, or conspiracy requirement of Sherman Act Section 1.

Kreuzer v. Am. Acad. of Periodontology, 735 F.2d 1479, 1485 (D.C. Cir. 1984); see United

States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 58 (D.C. Cir. 2001).6

Landmarks complaint meets these requirements. It adequately alleges violations of the

Sherman Act under both the Paramount substantial competition test and the modern rule of

reason, and it alleges specific facts permitting the plausible inference of concerted conduct.

A.

Regals Blanket Clearance Fails the Paramount Substantial Competition Test

In its landmark Paramount decision, the U.S. Supreme Court announced: There should

be no clearance between theatres not in substantial competition. 334 U.S. at 146. The Court

recognized the following factors as bearing on whether two theaters are in substantial

competition and thus whether a clearance is unreasonable.

(1) The admission prices of the theatres involved, as set by the

exhibitors;

(2) The character and location of the theatres involved, including

size, type of entertainment, appointments, transit facilities, etc.;

(3) The policy of operation of the theatres involved, such as the

showing of double features, gift nights, give-aways, premiums,

cut-rate tickets, lotteries, etc.;

(4) The rental terms and license fees paid by the theatres involved

and the revenues derived by the distributor-defendant from such

theatres;

(5) The extent to which the theatres involved compete with each

other for patronage;

(6) The fact that a theatre involved is affiliated with a defendantdistributor or with an independent circuit of theatres should be

6

Landmarks attempted monopolization claim also requires an allegation of Regals intent

to monopolize, see Spectrum Sports, Inc. v. McQuillan, 506 U.S. 447, 456 (1993), but Regal

does not arguenor could itthat the complaint fails to allege this element. See Compl. 119.

- 14 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 24 of 54

disregarded[.]

Id. at 145-46; see Quad Cinema Corp. v. Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corp., 1983 WL 1822, at

*6 (S.D.N.Y. May 12, 1983) ([T]he reasonableness of a clearance policy . . . is nothing more

than the converse of the question of what constitutes substantial competition in a given case.);

Seven Gables Corp. v. Sterling Recreation Org. Co., 1987 WL 56622, at *9 (W.D. Wash. June

25, 1987) (A clearance may only be granted against a theater in substantial competition with

the theater obtaining the license.).

Thus, under Paramount and its progeny, clearances between two theaters not in

substantial competition violate the Sherman Act, without the need to define the boundaries of a

relevant market or the defendants power in that market, or otherwise engage in a full-blown

rule-of-reason analysis. For example, in Paramount, the Supreme Court affirmed the district

courts finding that the clearances in that case had no relation to the competitive factors which

alone could justify them and held that that evidence was adequate, on its own, to support

the finding of a conspiracy to restrain trade by imposing unreasonable clearances. 334 U.S. at

146, 147. It upheld an injunction against the granting [of] any clearance between theatres not in

substantial competition. Id. at 147. And in Chicago Ridge Theatre Ltd. Partnership v. M & R

Amusement Corp. (Chicago Ridge II), 855 F.2d 465 (7th Cir. 1988), the Seventh Circuit

specifically distinguished between the substantial competition test and the modern rule-of-reason

test: whereas the former asks only whether the two theaters are in substantial competition, under

the rule of reason, the plaintiff must show the defendants market power. Id. at 471.

Notably, the Chicago Ridge II court explicitly acknowledged that Paramount is the last

word from the Supreme Court directly addressing the antitrust ramifications of clearances in the

distribution and exhibition of motion pictures and thus remains controlling law. Id. at 470-71. In

other words, unless and until the Supreme Court revisits Paramount, a plaintiff can prove that

- 15 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 25 of 54

clearances violate the Sherman Act by showing that its theater is not in substantial competition

with the defendants, without defining a relevant market, showing the defendants power in that

market, or demonstrating that the anticompetitive effects of the clearances outweigh any

procompetitive benefits proffered by the defendant. See, e.g., Reading II, 2007 WL 39301, at

*10-16 (evaluating clearances (a) as exclusive licenses under modern rule of reason, and

separately, (b) as clearance agreements under Paramounts substantial competition test).

Landmarks complaint alleges with factual specificity that its Atlantic Plumbing theater is

not in substantial competition with Regals Gallery Place. On the first Paramount factor

admission pricesthe complaint alleges that Landmarks ticket prices are up to 30 percent lower

than Regals. Compl. 43. The character and location of the theatres involved, including size,

type of entertainment, appointments, transit facilities, etc., Paramount, 334 U.S. at 145, also

militate against a finding of substantial competition. Landmarks theater has less than half of the

screens and one-tenth of the seats of the Gallery Place. Compl. 39, 41. And unlike the routine

(and shopworn) facilities at Gallery Place, Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing theater offers a fullservice bar and upscale food items; allows patrons to bring alcoholic beverages into the

auditoriums; offers reserved seating; and features oversized, plush leather seats. Id. 40, 42.

Landmark also alleges minimal overlap in the theaters respective patronage, see Paramount,

334 U.S. at 145: while the Gallery Place attracts large, loud, and often unpleasant crowds

(including teens and children), Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing theater caters to a more mature

audience seeking a more refined movie theater experience. Compl. 40, 83. Finally, for years

before it closed, Regal played day and date with an even closer and more similar theater. Id.

63-65. These factual allegations, which must be taken as true, support a plausible inference

- 16 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 26 of 54

that Regals and Landmarks theaters are not in substantial competition. If they are not, Regals

blanket clearance violates the Sherman Act.

Regal improperly ignores these allegations and misconstrues the complaint in arguing

(Motion 31-32) that the two theaters substantially compete for the same customers. First,

Regal falsely states that the complaint expressly asserts that the Atlantic Plumbing theatre is in

competition with [the Gallery Place] for many of the same patrons. Motion 31 (quoting Compl.

53) (alterations in original). In fact, that paragraph of the complaint alleges only that Regals

pattern of demanding blanket clearances over Landmarks Atlantic Plumbing theater, but not

farther-afield theaters, reflects Regals estimation that only the Atlantic Plumbing theaterand

not the farther-afield theatersare in competition with the Gallery Place at all. Compl. 53

(emphasis added). The complaint alleges substantial differences between the two theaters

customer bases, see id. 40, 83not, as Regal argues, the opposite.

The only other allegations Regal cites for its substantial competition proposition are

allegations in the complaint supporting an inference that there is any competition at all between

Regals and Landmarks theaters. See Motion 31. But Paramount requires the plaintiff[] to

show the absence only of substantial competition, not the absence of all competition. Chi.

Ridge Theatre Ltd. Pship v. M & R Amusement Corp., 732 F. Supp. 1503, 1512 (N.D. Ill. 1990)

(second emphasis added). Indeed, Regals argumentthat an allegation of any competition

between two theaters negates an allegation of no substantial competition and renders a clearance

- 17 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 27 of 54

presumpti[vely] . . . lawful) (Motion 32)is a twist of logic that would defeat all unlawful

clearance cases and is not the law. Quad Cinema, 1983 WL 1822, at *6 n.6.7

Finally, Regals argument that Landmarks complaint fails the substantial competition

test (Motion 32) cites exclusively summary judgment cases and one bench trial case in which

courts made the substantial-competition determination on a full record. Those cases are

inapposite here, at the motion to dismiss stage. See Reading Intl, Inc. v. Oaktree Capital Mgmt.

LLC (Reading I), 317 F. Supp. 2d 301, 321-22 (S.D.N.Y. 2003). Because Landmark alleges

facts supporting a plausible inference that its Atlantic Plumbing theater is not in substantial

competition with Regals Gallery Place theaterwhich must be taken as trueLandmarks

Sherman Act claims survive Regals motion to dismiss.

B.

The Complaint Adequately Alleges Sherman Act Violations Under the

Modern Rule of Reason

As discussed, Landmarks antitrust claims survive Regals motion to dismiss without the

need to establish a prima facie case under the modern rule of reason. But Landmarks complaint

does this, too. Specifically, Landmark pleads direct and circumstantial evidence of Regals

market power, and that Regal has engaged in exclusionary conduct that has harmed competition.

Under the modern rule of reason, a plaintiff shows a violation of the Sherman Act by (1)

making a threshold showing of the defendants market or monopoly power and (2) establishing

that the defendants conduct was anticompetitive. See Leegin Creative Leather Prods., Inc. v.

PSKS, Inc., 551 U.S. 877, 885-86 (2007); Microsoft, 253 F.3d at 58-59. Market or monopoly

power is the power to control prices or exclude competition and can be proven by either direct

As discussed above, Landmarks allegation of no substantial competition is not

inconsistent with its allegations of some competition between the Gallery Place and Atlantic

Plumbing theaters. In any event, a plaintiff may properly plead alternative theories of liability,

regardless of whether such theories [a]re consistent with one another. Scott v. District of

Columbia, 101 F.3d 748, 753 (D.C. Cir. 1996) (citations omitted); see Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(d)(3).

- 18 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 28 of 54

or circumstantial evidence. Microsoft, 253 F.3d at 51; Image Tech. Servs., Inc. v. Eastman Kodak

Co., 125 F.3d 1195, 1202 (9th Cir. 1997). Direct proof of market power is evidence that a firm

has profitably reduced output and raised prices above competitive levels or excluded

competitors. Microsoft, 253 F.3d at 51 (citing FTC v. Ind. Fedn of Dentists, 476 U.S. 447, 46061 (1986)); Theme Promotions, Inc. v. News Am. Mktg. FSI, 546 F.3d 991, 1001 (9th Cir. 2008);

Re/Max Intl v. Realty One, Inc., 173 F.3d 995, 1018 (6th Cir. 1999). Circumstantial proof of

market power, by contrast, involves an examin[ation] [of] market structure. Microsoft, 253

F.3d at 51. Under this structural approach, monopoly power may be inferred from a firms

possession of a dominant share of a relevant market that is protected by entry barriers. Id.; see

Theme Promotions, 546 F.3d at 1001.

Because market share and barriers to entry are merely surrogates for determining the

existence of monopoly power, . . . direct proof of monopoly power does not require a definition

of the relevant market. Broadcom Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc., 501 F.3d 297, 307 n.3 (3d Cir.

2007) (collecting cases). As the D.C. Circuit has explained, [t]he definition of the relevant

market has no independent significance under the Sherman Act. It relates only to the

determination of whether a defendant possesses monopoly power. S. Pac. Commcns Co. v. Am.

Tel. & Tel. Co., 740 F.2d 1011, 1020 (D.C. Cir. 1984); see Ind. Fedn of Dentists, 476 U.S. at

460-61. As such, an antitrust plaintiff is not required to rely on indirect evidence of a

defendants monopoly power, such as high market share within a defined market, when there is

direct evidence that the defendant has actually set prices or excluded competition. Re/Max Intl,

173 F.3d at 1018; see United States v. Visa U.S.A., Inc., 344 F.3d 229, 239 (2d Cir. 2003); see,

e.g., In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., 968 F. Supp. 2d 367, 389 (D. Mass. 2013)

- 19 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 29 of 54

(This Court need not engage in an extensive analysis of circumstantial evidence of market

power because direct evidence of such power is available.).

1.

The Complaint Alleges Direct Evidence of Regals Market Power

Regal argues (Motion 17) that Landmarks non-circuit dealing claims must be dismissed

if Landmark fails to allege a plausible relevant market and that, without a relevant market,

Landmark cannot prove that Regal has market power. As already discussed, Regal is wrong.8

Regals ability to reduce output, raise prices, and exclude competitors is direct evidence

of its market power. Landmark has alleged that its Atlantic Plumbing theater offers a superior

consumer experience than does Regals Gallery Placewith its dirty bathrooms, long lines, old,

traditional theater seats, substantially fewer amenities, and a generally less pleasant environment.

Compl. 40, 42. The Gallery Place nevertheless charges up to 30 percent more for reserved

tickets. Id. 43. This is direct evidence that Regal has market powerthe power to raise prices

above and to reduce output (here quality) below competitive levels. See 11 Phillip E. Areeda &

Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles and Their Application

(hereinafter Areeda) 1912f (3d ed. 2011) (reduction in quality constitutes reduction in

output); see also Babyage.com, Inc. v. Toys R Us, Inc., 558 F. Supp. 2d 575, 583 (E.D. Pa.

2008) (Hallmarks of . . . actual harm [to competition] include an increase in retail prices above

and beyond what they would be under competitive conditions, a reduction in output below what

it would be under competitive conditions, and a deterioration in quality and service.).

The cases Regal cites for the proposition that [e]stablishing the contours of the

geographic market is the necessary predicate for alleging Landmarks rule-of-reason claims

(Motion 17) stand instead for a much more limited proposition: that when a plaintiff proceeds

only on a market-structural (circumstantial evidence) approach to establishing market power, a

well-defined relevant market is required. When the plaintiff presents direct evidence of market

power, it is not.

- 20 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 30 of 54

Further direct evidence of Regals market power is its ability to exclude Landmarks

theater from access to desirable first-run commercial films by strong-arming all of the

distributors into licensing almost all such films exclusively to Regals Gallery Place theater,

notwithstanding the distributors contrary business interests in licensing films for day-and-date

play at multiple theaters. Compl. 73. Indeed, Regal concedes in its motion that it has been able

to do so solely because of its sizei.e., power in the marketrelative to Landmark. See Motion

9 (arguing that Regals Gallery Place has secured virtually all of the film product in the District

Core because it offers significantly more seats). This is perhaps the most convincing direct

evidence of Regals market power:

Dealers cannot force an unwilling manufacturer to restrict

intrabrand competition to their advantage unless they possess some

power over it. Of course, there is no better demonstration of power

than its exercise. Suppose, for example, that a manufacturer

explicitly declared that distribution restraints would be inefficient

but nevertheless adopted them after dealers threatened, Restrain

intrabrand competition or we cease handling your product. The

resulting restraint could then be readily attributed to dealer power

and fairly judged unreasonable.

8 Areeda 1604g.9 Because Landmark has alleged direct evidence of Regals market power, its

rule-of-reason claims survive regardless of whether Landmark has alleged a plausible relevant

market.10

See, e.g., Visa, 344 F.3d at 240 ([Plaintiff], despite repeated recent attempts, has been

unable to persuade any issuing banks . . . to utilize its network services because [defendants]

exclusivity rule would require such issuing banks to give up membership in [defendants]

consortiums, and banks are unwilling to do so. In short, [defendants] have demonstrated their

power in the network services market by effectively precluding their largest competitor from

successfully soliciting any bank as a customer.).

- 21 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 31 of 54

2.

The Complaint Alleges Circumstantial Evidence of Regals Market

Power

As discussed, Landmark has alleged direct evidence of Regals market power, thus

obviating the need to allege Regals market power through a market-structural approach. But

Landmark has alleged that too.

The relevant market is defined generally as the area of effective competition, Brown

Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 324 (1962), to which the purchaser can practicably

turn for supplies, Tampa Elec. Co. v. Nashville Coal Co., 365 U.S. 320, 327 (1961). [S]uch

economic and physical barriers to expansion as transportation costs, delivery limitations and

customer convenience and preference and [t]he location and facilities of other producers and

distributors are essential in determining the relevant geographic market. L.A. Draper & Son v.

Wheelabrator-Frye, Inc., 735 F.2d 414, 423 (11th Cir. 1984). [M]arkets involving services that

can only be offered from a particular location, like movie theaters, will often be defined by

how far consumers are willing to travel. Cobb Theatres, 101 F. Supp. 3d at 1336 (quoting Earl

W. Kintner, Federal Antitrust Law 10.15 (2013)); see T. Harris Young & Assocs., Inc. v.

Marquette Elecs., Inc., 931 F.2d 816, 823 (11th Cir. 1991) (customer convenience and

preference . . . must be considered in determining whether consumers within the geographic

area cannot realistically turn to outside sellers should prices rise within the defined area). But

unlike [b]usiness firms [that] maximize profits, which depend on the cost and value of such

inputs as fuel, wages, and the like[,] . . . consumers . . . place different subjective values on their

10

See, e.g., W. Duplicating, Inc. v. Riso Kagaku Corp., 2000 WL 1780288, at *5 (E.D. Cal.

Nov. 21, 2000) (denying defendants motion to dismiss because it was directed solely at

[plaintiffs] circumstantial proof of market power but plaintiff had alleged direct proof of

market power, which was sufficient); High-Tech Employee, 856 F. Supp. 2d at 1122 (denying

motion to dismiss for failure to allege plausible relevant market because defendants market

power was established with allegations that they succeeded in lowering the compensation and

mobility of their employees below what would have prevailed in a lawful and properly

functioning labor market); Nexium, 968 F. Supp. 2d at 389.

- 22 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 32 of 54

time and willingness to travel. These differing values cannot readily be captured by

transportation costs or other objective factors. 2B Areeda 553a.

Thus it is not surprising that [t]he Supreme Court has recognized that an element of

fuzziness would seem inherent in any attempt to delineate the relevant geographical market, and

therefore such markets need notindeed cannotbe defined with scientific precision. FTC v.

Sysco Corp., 113 F. Supp. 3d 1, 48 (D.D.C. 2015) (quoting United States v. Conn. Natl Bank,

418 U.S. 656, 669 (1974) (quoting United States v. Phila. Natl Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 360 n.37

(1963))); id. at 51-52 (defining relevant market is thorny task). For this reason, dismissal at the

Rule 12 stage for failure to allege a relevant geographic market is disfavored. Todd v. Exxon

Corp., 275 F.3d 191, 199-200 (2d Cir. 2001).11

Moreover, [t]here is no requirement that the market definition elements of the antitrust

claim be pled with specificity. High-Tech Employee, 856 F. Supp. 2d at 1122 (alteration

omitted). An antitrust complaint therefore survives a Rule 12(b)(6) motion unless it is apparent

from the face of the complaint that the alleged market suffers a fatal legal defect or the alleged

market definition is facially unsustainable. Id.

The complaint here alleges that the relevant geographic market is the District Corethe

densely populated area of Northwest Washington, D.C. roughly bounded to the northwest by

Rock Creek/Rock Creek Park. Compl. 44. Consumers desiring to see a movie and already

present in the District Core (whether for work, shopping, or some other reason, or because they

live there) generally do not travel outside of this area to attend a theatrical film exhibition, and

11

See E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. v. Kolon Indus., Inc., 637 F.3d 435, 442 (4th Cir.

2011) (determining the relevant geographic market is a fact-intensive exercise centered on the

commercial realities of the market and competition); Syufy Enters. v. Am. Multicinema, Inc.,

793 F.2d 990, 994 (9th Cir. 1986) (Relevant market is a factual issue which is decided by the

jury.).

- 23 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 33 of 54

would not do so even if prices increased a small but substantial amount. Id. 45-46. This

reluctance to travel outside the Core once in it to see a movie is driven by a variety of factors that

differ from consumer to consumer, including the time and expense of traveling farther afield,

the discomfort and uncertainty associated with visiting unfamiliar neighborhoods, the Metroinaccessibility of some theaters outside the zone, and high population density and heavy traffic

congestion in the District Core. Id. 47, 51-52.

These allegations are sufficient to establish the relevant market at this stage of the case.

See, e.g., Cobb Theatres, 101 F. Supp. 3d at 1336 (plaintiff adequately demonstrated why the

market should . . . exclude . . . theatres farther afield from the relevant market but within the

same metropolitan area by alleging that moviegoers in the [alleged relevant market] are not

willing to travel outside of the area to watch movies because of significant population density

and heavy traffic congestion); IHS Dialysis Inc. v. Davita, Inc., 2013 WL 1309737, at *5

(S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2013) (plaintiffs sufficiently pled relevant geographic markets comprised of

distinct subregions of metropolitan areas where plaintiffs alleged consumers were unwilling or

unable to travel long distances to obtain relevant services).

None of Regals arguments supports dismissal. First, Landmark does not admit

(Motion 18) that many other first-run commercial theatres are located right outside the District

Core. To the contrary, the complaint alleges with factual particularity why AMCs Loews

Georgetown 14, AMCs Courthouse Plaza 8 near Arlington, AMCs Uptown 1 in Cleveland Park,

AMCs Mazza Gallerie in Friendship Heights, ArcLights North Bethesda theater, and Regals

Bethesda theater are generally not reasonable alternatives for the theaters in the District Core.

For example, AMCs Georgetown theater has no Metro stop, Compl. 51, and the same is true

for ArcLights North Bethesda theater. The Gallery Place and Atlantic Plumbing theaters are

- 24 130984953.1

Case 1:16-cv-00123-CRC Document 17 Filed 05/19/16 Page 34 of 54

within walking distance of vast swaths of the District Core and are also familiar to consumers

therein; neither can be assumed true of theaters in Arlington, Friendship Heights, and Bethesda.

Id. 47. And driving times to theaters outside the District Coreparticularly given heavy traffic

congestionsubstantially exceed the time required to get to theaters within it. Id. 52. Moreover,

that Regal has demanded clearance over Landmarks theaterbut not the other theaters it argues

should be included in the market, see id. 53is further circumstantial evidence that Regal

views Landmarkbut not these other theatersas its competition. See Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at

325 (boundaries of . . . []market may be determined by examining such practical indicia as

industry or public recognition of the []market as a separate economic entity) (contra Motion 24

n.8). Although a defendants trade area does not by definition constitute a relevant market, here

Regals internal view of competition in the District Core is at least a factor relevant to the

analysis. For Rule 12 purposes, Landmarks detailed factual allegations are sufficient to establish

the plausibility of the District Core as the relevant market.

Next, cherry-picking specific routes, Regal quibbles (Motion 19-21, 23 n.6) that

consumers at the extreme southwest periphery of the relevant market are physically closer to

AMCs Georgetown theater, and have a shorter Metro ride to AMCs Courthouse Plaza theater