Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Architecture of Oman

Uploaded by

Pavneet DuaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Architecture of Oman

Uploaded by

Pavneet DuaCopyright:

Available Formats

FOREWORD

Much of Oman's existing vernacular architecture stands unoccupied. I do hope that this book helps to change this. These buildings deserve rehabilitation and preservation. They are both very beautiful and of great importance as a record of the cultural context of the urban fabric, the architectural heritage and the social customs of Oman. The material presented here persuades me that the Omani people's pride in their traditional way of life is the main guarantee of continuity in the urban context. I pray that the professionaIs understand how important it is that this cultural identity informs future housing policy. The scale of vernacular architecture in Oman is always human. This fact derives from the use by master craftsmen and builders of parts of their body as units of measurement during the building process. Local materials have served generations of Omani master builders well, by translating their skill and imagination into an archtecture integrated with the natural environment from which they have gained so much of their inspiration. The materials - stone, mudbrick, wood, lime and a mud plaster, known as sdmj, particular to Oman - have provided the craftsman with the means to produce an architecture distinguished, for example, by the contrast of expressive details and decoration against the massive solidity of the rendered walls. Such detailing can be seen in the wide variety of drdyish (window niches), masbr~biwab (wooden window screens) and ornate carved doors. The future of Oman's forts, the quality of which is now widely acknowledged, has been ensured through recent public works, which have given us a series of beautifully restored buildings throughout the Sultanate. Dr D d u j i ' s research now extends our awareness of Omani architecture to include the beauty and simplicity of its mosques -which deserve to be cherished in the same way - and residential quarters. I pray that in so doing it will suggest a wider context for the preservation of the architectural heritage of Oman - and stimulate all of us in the English-speaking world who care about these buildings to give Oman's efforts to preserve and care for them our active and whole-hearted support. I congratulate the author and commend this book most warmly to you.

HRH The Prince of Wales

Introduction

The f q d e of Bayf a Mjoddrirnh 1

he Sultanate of Oman is situated on the Arabian Sea, between Yemen to the south-west, Saudi Arabia to the west and the United Arab Emirates to the northwest. There are similarities between these counmes due to shared influences in the southern and eastern Arabian coastal strip - for example, Oman shared the influx of Indian, East African and Portuguese influences with Aden and Hadramiit - and internal mbal affiliations. Trade relationships between the Yemen and the Sultanate were Erst established when the routes for frankincense and other goods ran between Dhofar in the south of Oman and the kingdom of H a h i i t in Yemen. Evidence can be found in Ibn Battiitah's Travels, Ibn a1 Mujzwir's treatise and Marco Polo's Travels' for strong links between the peoples of Dhofar and Yemen. An ear-

lier reference in the Qur'ato the mbe of 'Ad may have a bearing on this, since the 'city of gold' they built, which is given as being in the land of Aden, may in fact have been in Dhofar.' However, the specific geographical location and history of the Sultanate of Oman mean that despite these similarities there is a continuity of style, steeped in Arab culture, that distinguishes its architecture from that of the rest of the peninsula. Confronting the present in a land with such an ancient past, particularly through such a tangible medium as architecture, is complex, as there is a cultural tendency to accept the present without analysing the underlymg premises which brought it into being. What is evident, however, is that in early Arabia geography and the trade routes were the primary force influencing

THE ARCHITECTURE O F O M A N

architecture until the time that historical events began to impinge, establishing cities, capitals and borders, and fostering specific cultural identities and destinies. In Muscat and Dhofar architecture amalgamated into urban townhouse styles bearing a relationship to those of Aden and Ha&mut respectively. In the late nineteenth century, a modified vernacular type developed in Muscat in parallel to the colonial style, typified by the British Embassy which stood until 1995 near the Diwan of the Royal Court. Though differences between the vernacular Muscat house and, for example, the mansions of a1 Manzafah in lower Ibra' may be immediately obvious, their shared architectural language is more specific than that of the urban enclaves of any neighbouring area. The types of vernacular architecture are sustained throughout the Sultanate. A spirit of minimalism and austerity, associated with the nature of the 'Iba& sect,' dominates the vernacular architectural styles and forms of the Sultanate. In turn, this ethos disciplines and refines the extent and form of urban growth, and is embodied in the understated style of the modem buildings of Muscat. Legislation, unprecedented in the Gulf region, restricts the scale of buildings, both in the number of storeys and in the limitation of high-rises to commercial areas. Elsewhere in the Middle East, the quest for fast urban development has had irrevocable consequences, as the forms of new cities were determined by the characteristics of quick, commercial construction, which omits the essential component that gives substance to the vernacular architecture of the region, both Islamic and Pre-Islamic: the creative process of design. The changes in the urban structure of the Sultanate were initiated by His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Sa'ld bin Taymiir K1 Sa'id on his accession to power in 1970. Muscat and M u ~ a h town located two miles west of (a Muscat) were geographically and historically severed from the mainland, two isolated enclaves on the rugged coastline. Inhabitants leaving the coast for the interior would say they were 'going to Oman'. Sultan Qaboos was able to establish hegemony over both areas, and in order to remove the distinctions embarked almost immediately on an integral development plan, with the aim of

achieving development which would be equitable throughout the country. The plan provided for the expanding population to be accommodated in modern towns, and encompassed the creation of new urban centres and roads, the institution of modem health care, education and social reforms, and encouraged enterprise and investment in the Sultanate'snew administrative and economic structure.' Architecturally, until 1970Muscat and other towns in the Sultanate consisted of clusters related in form and organisation to the vernacular urban settlements of Arabia and North Africa. Walls surrounded cities and some towns; the architectural fabric consisted of local materials; the height of buildings was resmcted to three storeys (four in the case of distinguished town palaces and mansions); and socio-economic life was centred around aibal communities engaged in a combination of fishing, trade, agriculture and grazing, according to the location and historic links of each settlement. Sadly, I was unable to fulfil my immense desire to experience the towns of the various regions in the Sultanate while they were still mhabited. The need to interact with the architecture and to observe the socioeconomic environment specific to each walled town or quarter - how each piece of the urban fabric was structured and functioned within a complex set of relationships - cannot be underestimated. Forming an image of the original architecture from what appeared to be no more than archaeological remains was a particularly difficult feat for an architect. On many occasions, while wandering the dark passages of an uninhabited quarter, the silence and the inscrutability of the past hovered overwhelmingly. Deserted and dilapidated urban fabric, like walls, is mute. Each town or city had its own narrative consisting of the life on the streets and other public and private spaces, which remains unknown and untold. The absence of any records of the history of this architecture, or local accounts of the socio-economic life that accompanied the panoply of architectural styles, was another difficulty. This was as true of Muscat as of the other areas of the Sultanate, and a literary search among the published texts of travellers or writers who were in the main indifferent to the architectural culture and

INTRODUCTION

miit,

heritage of Oman proved unsatisfactory. This book does not attempt to be a definitive record of Omani architecture. Rather, it is the result of research into and documentation of the prominent architecture of selected towns and quarters in the Sultanate visited by the author over a relatively brief period, 1993-97. The book is intended to establish a reference point and provide a formal framework that may assist, and hopefully inspire, architects, urban policy-makers, academics and artists. Further, more specific research into this rich but relatively neglected field is required to redefine and recognise the cultural heritage that accompanies the architectural tradition. Unfortunatelymany of the architectural surveys originally planned for this book proved impossible to conduct I have chosen to arrange the book according to the modem regional administrative divisions of the Sultanate, as they are well suited to the task of defining architectural enclaves and styles. These are Muscat (the capital), al Biilnah (the coast), Musandam (a northern peninsula separated from the rest of the Sultanate by a part of the United Arab Emirates), al Dakhiliyyah ('the interior'), al Zahiiah (also a region of the interior), al Sharqiyyah(the eastern region) and Dhofar in the south. Each is divided into provinces which carry the names of prominent cities or towns. The eighth region, a1 Wusta (the cenaal region), which includes the towns of H a p & al Daqm and alJazir, was not visited for this book. The vast desert expanse of the Sands that constitutes al Wusm, which borders on the Empty Quarter, would have provided an interesting contrast; however, along with the desert extension of Shkr at the edge of Ramlat Fasad in northern Dhofar, it has been allocated to the continuing research that has resulted from the present project. Through the support and interest of Sultan Qaboos University and the Diwan of the Royal Court, the preliminary work represented in this book will be developed in the years to come, enhancing its value as an architectural and cultural record. In the summer of 1973,I met the Egyptian architect Hasan Fathy (d. 1990) in Beirut. He had recently returned from a visit to the Sultanate, during which he had been contemplating working on integrating new

architectural design with the vernacular architecture of the prominent cities in the Sultanate. At the suggestion of Hasan Fathy, a team from the Architectural Association School of Architecture -its members were Omar el Farouk, Allan Cain, Farokh Afshar and John Norton - carried out field research in 1973. The study took place barely three years after Sultan Qaboos had come to power, at a time when very little change had occurred in the living patterns of most Omanis. Thevast majority of Oman's towns and villages, and their building methods, had remained unaltered for centuries. The material which they gathered provides an invaluable reference point, as it contains information on much architecture that has subsequently disappeared. An abridged version of their unpublished monograph appears in Chapter 1of this book. Because of their detailed knowledge of the important forts and palaces which they restored, I also invited Dr Enrico d'Errico and Olivier Sednaoui to contribute to the book.

Salma Samar Damluji LondmL, October 1997

C H A P T E R

Traditional Architecture and Settlement Patterns

Ahre:

The murtymd ofBo$ d Rudaydah

in BirLat d

Mmvr

Opposite The f d a j ofBnyt el Rudaydnh in Birkat d M m z

TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE A N D SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

Regional Styles and Building Traditions

)rbove:Close-upof

the walls of nl Fiqayn E a t near Mnnah

Opposite An interior shot of

Nnnra Foe rhowrllg the m m h u c t e d dome of the mosque

Introduction

The forts and citadels of Oman represent the most obvious feature in traditional Omani architecture. Crowning cities and commanding the entrances to towns, they continue to have a dominant presence in the urbanlandscape. The design layout and building technology of this fortified architecture, which included residential spaces, is indicative of the level of sophistication that town planning and architecture reached in settlements across the Sultanate. The forts have remained a focal point for visitors to the country and a basic historic reference for the surrounding fabric of adjacent towns, despite the removal, through renewal or reconstruction, of the surrounding traditional urban fabric. The forts and towers have been restored through an ongoing national campaign that has been in effect for the lasttwo decades and which has, despite the courses of renovation and restoration, preserved the exceptional value of these complex structures.' However, the architecturalheritage of Oman, though symbolised by these forts and towers, and explored through them in several publications, is not exclusive to them. Oman boasts an i n t e r e s ~ g and important vernacular architectural fabric that is just as rich and diverse as those imposing buildings. The development of vernacular architecture in the Sultanate is closely related to the evolution of some of the earliest urban settlements in Arabia. A wide range of iduences, from the Pre-Islamic, Islamic, Persian, Portuguese, Moghul and South-East Asian to

the H a b style of neighbowingYemen and firrally the n buildings of East Africa, is also discernible i many of the regional variations. Whereas some of these intluences are expressed with direct references (most obviously, the Pormguese fortifications at Muscat and the &hami influence in Dhofar), others are more vague. An examion nation of the architecture of t w ssuch as N a m , Misfst a1 'Abriyyin and al Mubyrib demonstrates the importance of establishing references for each style, though the styles themselves are ultimately specific to Oman. Other towns, such as al Minzafah, illustrate an established and formal domestic architectural style within a developed urban town centre, with possible influences that may have been brought in by wealthy merchants from Zanzibaror East Africa. To define fully the overlapping influences requires further research into the cultural influx that occurred during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (including research into the social fabric that was attached to the architecture), which is beyond the scope and speciality of this book.

Above The shrine of Muhammlld bm 'A7i in Mirbaf cemetery, which has n typtcd Hndrami drsrgn. i a c l o r s ~ r exmple of Ule mf/uences behuem Dhofor ond southern Yemm. Cross-refeencer are rare on f m e r orch,femnol iweis, ~spedaliy mqms and r e I z p w buildings in

Below left and right

Detnih from the town ofMirat a7 ' A w n in oi H~wd'proM'nce

10

T H E ARCHITECTURE O F OMAN

F a r left

Detnil of a c m d wiwdw meen frrmT a h o w in M&8F

Left

Detail ofan enolhoncedwr to orre of TEqah'r old hours

B d o r ilnd botmm

The rmvatul mosque of&arat rrl i'irni', Adm

Even when obvious influences do occur, the detailing of the buildings - such as the carved window screens, the doors, the carved mud, lime plaster and stucco work, and the painted ceilings and calligraphic inscriptions expresses important stylistic variations owing to the differing interpretations of local master builders and craftsmen. Local types became established in the architecture of the different regions, which employed local building materials, technology, design and town planning forms that vary remarkably between the coast and the interior, and between the eastern and southern parts of the country. Yet despite the regional differences, the similarities found in the plans and designs of both mosques and residential buildings clearly point to specific characteristics that evolved in and became exclusively attached to the architecture of the Sultanate. However, the paucity of vernacular architecture makes the task of locating intact and cohesive examples dif3icult: a problem compounded by the fact that many of the more interesting settlements that survive are widely scattered. Many of the examples of traditional domestic architecture in Oman are in a dilapidated state, their owners having deserted the old quarters in h o u r of the newly developed and more prestigious modem parts of towns and cities. Mosques are an exception to this trend since they remain in continuous use, and in some cases have even been renovated. One such example is in the Harat a1 Jami' quarter of Adm, which is now deserted with the sole exception of the renovated mosque of KI BiiSa'zd. Other mosques that have been renovated through the

T R A D I T I O N A L ARCHITECTURE A N D SETTLEMENT P A T T E R N S

13

o p p * &hi1 of the intnnnl fW& of the h e - s t o r e y hovres i tke n town of @IMudaybi

T% deserted t m o f H y n d HmyBhrm in A&. Sinsle- and dwble-stow residentid buildinn were conrtrudcd in the c o n e - s W bm d. ~ ~ l a r r reilztul es unditionczi - t p p m m Gtain throughout the imegralsburturc of the town

tsa

but of the urban centres of the Sultanate in general, and forms the basis of the following description of building techniques. According to Shaykh M h n d , the master builder was traditionally responsible for designing the houses of ordinary people. The houses belonging to the 6lite were designed to a large extent by the owners themselves. Examples of houses built for shaykbs still s d v e in many towns. Once the plan of the building was determined and marked out on site, the foundation trenches were dug. These varied in depth from 60 centimetres to 1 metre. For the foundations themselves, courses of stone set in sftt-zzj lime mortarA were used if the owners could afford it; if not, the stone courses would be arranged in an ashlar setting (closely packed stone with no mortar) known in Muscat as a17afi. Foundationswere between 20 centirnetres and 1metre deep, depending on the owner's means.

'

RilM Remnants of a stone wall shmving the r w a -

niche, Mirbdt

the absence of documentation, where the population has relocated to the modem urban environment of the newly constrncted quarters, stepping into the abandoned remaios of the original town affords the only tangible means of readingvernacular architecture'spast.

The Building Tradition

The few master builders skUed in traditional building techniques, materials and styIes still practising provide an important insight into the processes that created both individual buildings and settlements.Material from interviews with master builders has been included throughout the text of this b o While this often consists of descripok tions of methods, styles and terminology specific to certain locales, broad parallels are also evident One particdarly informativesource was Shaykh w i i d bin who, though not a master builder, is an ~ s h ia1 r eminent expert on historical buildings and vernacular building tedmipes? Information from discussions with ShaykhMalpnad bin &hir al -'I provides a valuable introduction to the building traditions not only of Muscat

LADlTlONAL ARCHITECTURE A N D

SETTLEMENT P A T T E R N S

27

The Buraymi Oasis

Buraymi Oasis, which gives its name to the surrounding area, is on the frontier with Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia and is the largest of several oases. It is not far from the western end of a1Jabal a1 Akhdar. Located in the hot conditions of the desert, the oasis environment modifies this climate; it is cooler than its surroundings due to the presence of trees and irrigation, but humidity is higher. In 1973, each oasis settlement obtained its water from afalaj system, supplied by a nearby mountain. A Buraym was l undeveloped, although its neighbouring settlement of al 'Ayn in the United Arab Emirates had developed into a substantial and wealthy town with oil revenues. Poor road links with the rest of Oman, however, conmbuted to the discrepancies between al Burayrm and a1 'Ayn. Once again, water was the main factor that influenced the original settlement pattern of al Buraymi, and houses were generally built on land not suitable for cultia vation and above the level atwhichf @ carried water into the settlement. The main towns and villages were all situated around the date gardens, including the mq and the forts. The streets were quite wide, providing little shade, and even secondary streets were not narrow enough to provide protection from the sun. Buildings were either one- or two-storey structures. Bnraymi rtiq was a completely covered structure, much of it with corrugated-iron sheeting, which conmbuted to extremely hot s e h g conditions. As well as the dnsrers of buildings around the fort and market, there were also houses scattered amongst the date gardens, set several metres above the level of the gardens themselves. Houses were thus protected from flooding, which was not uncommon. Because of the climate, insulation was maximised in the buildings, which had small windows and thick mud walls. Roofs were constructed in the same way as in the northern uplands, although by the time of the study corrugated-iron roof sheeting was being introduced in several buildings, even though it created much hotter w o r h g and living conditions than the traditional materials. Conerete blocks were also beginning to be used and local builders said that there was very little mud-brick work being done.

The Muscat, M U Mand Ruwl Capital Region

This region covers the capital area from As Sib, at the southern end of the Batinah coast, to the mountains which run into the sea at the southeast, cutting off the area from the coast further west. There are four natural bays, two accommodating Muscat, the capital of Oman, and two M u & , which in 1973 was the new and expandingport. The region is close to the B a k a h coast and hence has a similar general climate, though this is modified by the surrounding bare rocky mountains. This is best exemplified in Muscat, where the town's protected harbour opens on to the sea, while the rest of the settlement is surrounded on three sides by steep rock faces. The light-coloured stone mountains around Muscat act as reflectors for solar radiation, focusing heat on to the town even after nightfall because of the heat storage capacity of the rocks.Muscat is said to have temperatures 5C higher than those of the surrounding country and therefore depends on local daily land and sea breezes. In 1973, Muscat and Muuab were the only two major established towns in the north of Oman, the latter with more room for expansion than Muscat, which was, however, the traditional seat of government In both, the ideal settlement climatically was one of narrow shaded streets that also allowed for air movement between the houses. However, Muscat and Mup& have different characteristics. Muscat functioned largely as a seat of power with the palace, embassies, government and commercial offices making it the wealthier residential area. The buildings in the settlementwere more widely spaced than in poorer Mumh. They were freestanding, larger, more spacious and better maintained. In 1973, this meant that cars could be more easily accommodated, and that houses were open to air movement. It also meant, however, that the wider streets were exposed to the sun and uncomfortable for pedesmans. The exception was the aq, which was compact, its shops separated by narrow, winding alleyways that were shaded and cool. M u d , on the other hand, had become the major trading centre of Oman. It was more densely built up with shops, houses and offices closely packed together. Streets were narrow and on a human scale, catering for the cart and the camel. In terms of shade, this was an

28

THE ARCHITECTURE O F O M A N

advantage. However where the car had begun to penetrate, the result was congestion. The houses in M u d were closely grouped, both physically and socially, into communal clusters. The most identifiable grouping was that of the Lawstip Quarter, the residential cluster built by the early Indian merchant community in the postPortuguese era. There are two access gates to this area, leading to narrow alleys. The houses are two or three storeys high and form a protective wl around the area, al with no openings at street level. At the time of the study, many of these buildings were in poor condition. In both Muscat and Muwah, the high population and the scarcity of available land for building had resulted in a relatively dense settlement pattern, albeit exhibiting the differences mentioned above. This meant that natural ventilation through the settlement was restricted, and other means had been found to encourage air movement and cooling. The courtyard house was one example, trapping cooler night-time air in the base of the courtyard. Another was window openings designed to facilitate air movement and to help keep interiors cool.

Tpical windows in the indigenous houses of Muscat and Mu& had multi-level openings; an example is shown here from Najwm House on the beachfront of Mu@&. This house had thick limestone walls which, due

Abve PrivmC house witn Onrete w h d m s , Mac@

Bettarn left sem'muhnwinsclim#ticr e s p m , typid t m h o w , Mwmt Bettam rylt

The harv of@%? 'AU NapBnl; g m d md Wt pwrplanr

1 auru*

cl

r.r.

'"""

ur~dur urrc Wonr c o o n

i"' '.<""

fw!d

"lma,

n*

cm a

hrr ( . u,

u k o ,rkll

u ,r hm m -,a

r m ro +?'

-,

-.

,A

n ,re

T R A D I T I O N A L ARCHITECTURE A N D SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

29

Top left

Gypsum-plaster soem, Muscat

TOP fi&

&dim s h w i i evaporative m l i n ~ s y r t e m window &4 end Bnyi a1 Z m v w ' (Mghnbb) in Mwcnt

Above Widmv screen detnil at Bnyt GI Zmvowi (Mughabbf in Murcat

the sea, to blow into the dwelling, but it was necessary to exclude solar radiation which would otherwise raise indoor temperatures. Two shading devices were used, one of which was a wooden awning-type consauction and the other a gypsum-plaster lattice window. The lattice windows of Muscat and Mutrah were generally elaborate, finely-detailed gypsum panels set into the wall. Their purpose was to allow daylight to enter and air to circulate, and to afford a view while excluding glare and solar radiation, as well as maintaining visual privacy. In the houses of the Muscatmu@& area, lattice openings were usually found in the upper portions of the window, or as high window and ventilation openings. Because of the air's high moisture content, the sky reflects a great deal of light and skies are much brighter than in dryer climates. The lattice-work screens (similar in function to the 'arishscreens on the Ba!inah coast) protect the eye from its harsh glare. Openings high up in rooms are also necessary to allow for the escape of warm air which collens in the upper reaches of a room due to convection. Another elaborate window design was found in the windows of Bayt al Zawawi (also known as Mughabb) in Muscat, which had incorporated an evaporative cooling system. The coolingunit used a porous, unglazed water jar, which was placed in the window opening, so that air entering the room passed over it. Water seeped through the water-6lled jar and kept the outer surface of the jar permanently moist Air passing over the surface caused the water to evaporate, absorbingheat energy, thus cooling the air and providing a supply of cool water in the jar itself for drinking. Once again, shading devices and lattice windows were used to prevent solar radiation from entering the room. This same evaporative cooling system, using porous water jars known as mazyarah, existed in Egypt and tests there have shown that it could reduce temperature by as much as 10C."

$m

to the material's thermal capacity, had a relatively constant temperature on their internal surfaces. Ventilation was therefore important for cooling. Muscat and M u d receive daytime onshore sea breezes which aid cooling. Windows were designed to allow this breeze, cooled by Located at the southern tip of the mountains which run through central northern Oman, $or developed as an important terminus for trade routes from the desert and Dhofar, at the pointwhere the Oman Gulf opens into the Indian ocean.

T R A D I T I O N A L A R C H I T E C T U R E A N D SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

Architecture in the Landscape

James Parry

Musondmn is one of the few places in Oman where raznfall lewlr me adequnh t czllmv searanal o cultivation. T m m s me conslmcted to secure maximum bolqit from the mndff

Introduction

Oman is one of the most arid countries in the world. Although the southern province of Dhofar @a&) is subject to the summer monsoon, known locally as the kbar$season,'l rainfall elsewhere is erratic, both in terms of quantity and frequency. Except in the mountains few weather stations in the northern and central portions of the c o u w report more than 80 millimetres of rainfall in any one year and months can pass without significant precipitation. Lengthy dry spells are often finallybroken by sudden cloudbursts of a violence and intensity that can cause the decimation of crops, loss of Livestock and extensive damage to buildings and infrastructure. Ironically, such rainfall does little to alleviate the constant problem of drought, as it is often extremely localized and evaporation rates are usually very high. In most areas the scant nature of the soil and vegetation encourages rapid run-off and rainfall is lost almost as quickly as it falls. The exploitation of such water reserves as do exist is therefore central to human existence in Oman and constitutes the chief determinant in agricultural and settlement patterns. Only in Musandam and Dhofar is a limited form of rain-fed agriculture feasible. Elsewhere it is necessary to harness and direct underground resources to create the conditions under which permanent settlement may thrive. Topography is therefore a critical consideration, as it dictates the ease with which subterranean water reserves can be exploited.

38

THE A R C H I T E C T U R E O F O M A N

Location of Water

Thegeography of northern Oman is characterized by chain of mountains that runs south from the C O ~ M U O U ~ the Straits of Hormuz parallel to the coast, until finally dwindling just inland from $iir, on the edge of Ja'lan. Although there are no major breaks in this chain, it is scored by a series of geological weaknesses which act as drainage lines and also provide a valuable opportunity for ,?*. communication routes. These two aspects are absolutely . central to the development of settlement and agriculture in Oman and, until the 1970s, it was in this region, ,immediately either side of the mountain range, that the country's greatest population density was m be found. The drainage lines take the form of gravel-based .. . wadis, which fan out into wider alluvial basins once they . leave the resmctive topography of the mountains proper. On the western side of the mountains the wadis flow . , ? - inland to the desert, whereas on the eastern side they . flow towards the sea, creating Oman's most productive

. '

Oman's wells are of little importance architecturally, their structuresbeing of quite rudimentary canstruction. Of much greater interest is the country's most renowned means of water management: the famous system ofwater channels, referred to collectively as a$@?.

The A B j

In such an arid country, the location, catchment, storage and distribution of water is of the utmost importance, requiring ingenuity and skilful management. Over the centuries, large-scale hydraulic systems have been developed in much of interior Oman in order to exploit precious water resources." These systems rely on conduits, which are constructed both below and above ground level. In Oman, the word aprfl is used as a generic term for all water conduits, whatever their provenance and design. those chanCosta identifies three different types of &: n e b g surface flow and run-off, those tapping springs, and those draining water-soaked suhsoil."The last two are essentially subterranean and, strictly-speaking, termed qamzt. An open channel is usually calledghayl." Some of Oman's @-j run for more than 30 kilometres, but most are between 3 and 10 kilometres long. An averagefalaj, or channel, supplies water a t a rate of 40 limes per second, which is enough to irrigate roughly 40 hectares of land. This can support a permanent settlement of about a thousand people or so. & The a ? transport water by gravity and a constant and relatively modest gradient is required to lead the water from the aquifer to a point of emergence at the surface, where it is collected, and thence to the place of use. Most of this journey is by means of the qanat, which has the advantage of reduced rates of evaporation and contamination. Once thefalaj emerges into the open air, it is usually collected in a cistern or reservoir, from which dismhntion continues via the ghql. These open channels then lead to the settled and cultivated areas, increasingly spawning, or dividing into, smaller channels to allow the water supply to service individual fields.

Opposite

R

.=

Y

. .

,,

~

.

"

agricultural region, al B s ~ a hHowever, nowhere do .

.. - - -. --, . .. . - .

~:

, .these wadis run constantly at surface level and most are e-. . ,, dry for at least part of the year. Alternative, more reliable, ,-. ', . sources of water are therefore required and must be

C -

1'

i. r. :

,

. _

-

. . .

i.

s.,

.$ <

~.

.

i

found by tapping underground aquifers. The most obvious mode of extraction from the aquifers is by sinking a well. Until the relatively recent advent of the diesel pump, most wells were operated by means of a pair of yoked animals, usually oxen or donkeys. The animals are attached to a rope which runs over a cog mounted within a tripod frame, the latter positioned over the well-head. As the beasts climb and then descend a ramp, the bucket at the other end of the rope is lowered into the water, hoisted up and then tilted into a cistern connected to a series of channels. The latter +then he used to dismbute the water as required. This -.-a *,+4fwell is usually called zajara and the whole network, includmg the associated irrigated area, is known as Gbiyab. Although once of widespread and frequent occurrence across Oman, this system is limited in terms of the area it can irrigate and in only a few regions do wells comprise the only means of irrigation (most littoral). notably the BHAlthough of social and historical significance,

A typic111

W - f wMisfit a1 'Ab"wn at

T R A D I T I O N A L A R C H I T E C T U R E A N D SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

41

Opposite F d a j nt Manal, showing (on right) the mdGd, the sporl heap reuitinrfrom excavmons to bring theground lwcl down to that of the f W

Bdow lee Fdaj el 'AWt - 'the demon's falaynear M q i d a1 KafF, o typical streetside falnl

The dismbution of the water transported by afahj must be designed sequentially to cater for the range of different uses and to avoid pollution from one use to another. Alinear utilization patxem is therefore employed; &e prerequisite is that drinking water is taken from the fahj as soon as it is collected from below ground, so that it is as clean as possible. Oman's are its lifeblood. The filaj channels bring the possibilities of life itself to an otherwise desolate and forbidding landscape. They dictate when, where and how the human inhabitants can make productive use of difficult terrain; they determine the extent and character of settlement patterns; and they involve the design and construction of particular featnres requiring formidable engineering and architectural skills. Although primarily functional, many of these features are of architectma1value, upon which forethoughtand a degree of aesthetic concern have been lavished. A are of great symbolic value and oken enjoy & an almost venerated status within the local community.

42

THE ARCHITECTURE O F O M A N

Fahzj water dislribufion

ILis is particularlyso in the case of the u r n , or mother channel, a source initially located by a water diviner and from which a network of smaller distributaries will usually stem. Celebrated aj@ such as Falaj D ~ r i s at Nazwa are part of local folklore and have assumed iconographic significancefar beyond their dady function as providers of water.'* Collectively, Oman's aj@ comprise the single most imporrant u d p g factor in the development of the people, landscape and settlements of the country's interior. They connect settlements both physically and psychologically, and remain an integral part of economic and cultural life.

History

The precise origins of the aFtj in Oman continue to be shrouded in mystery, despite extensive research and investigation.We still cannot be absolutely surehow old the oldest channels are. Popular myth revolves around a story concerning the prophet S u l a p bin Dawiid ~~~ More prosaically, ly suggested that ed from the similar system constructedininPersia. Persians occupied pans The of Oman at various times over many centuries from the Achaemenid to the Sassanid periods, and Oman's first aply' were thought to have been constructed during the Achaemenid occupation (sixth centuryB)' C." The Achaemenids were inveterate builders and

large-scale deve10pment of both land and water resources was the hallmark of their imperial conquests. An extensive construction programme, based on the precepts and design of the irrigation system in their homeland, would have been the obvious approach in a country of similar terrain and climate. Furthermore, we know from contemporary chronicles that the Persians deliberately sabotaged many aj7q in the face of the advancing armies ofthe Arabs at the time of Mlik bin Fabm and the A d diaspora (&a second century BC).IqWe may interpret this as evidence of a 'scorched earth' policy, whereby the Persians dismantled their own engineering. However, the existence of apparently indigenous a? in neighbouringYemenm indicate that those in & may Oman were equally spawned from local iniriative and necessity, rather than the result of outside involvement The evidence of a developed copper-mining industry in Omanduring the third millennium BC may shed further light;" the amaction and mining of copper would have reqnired the easy snppk of large amounts of water and it is difficult to see how this could have been achieved other than by a system such as the aj7q. Setded existence in Oman would have been equally unlikely without an imgation system to sustain it, and as evidence has come to light of settlements which are broadly contemporary with theancient mining industry," so the likelihood increases of Oman's aj&~ network substantially predating the Persian occupation. It is possible that it was

T R A D I T I O N A L ARCHITECTURE A N D SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

43

extended by the Achaemenids, but its roots are almost certainly earlier." Following the expulsion of the Persians and the advent of Islam, Oman's aflej suffered mixed fortunes. There is no evidence to suggest that any extension of the network took place, nor indeed that anydung other than basic maintenancewas carried out, until the period of the Ya'xribah imamate (1035-1157/1625-1744). On the contrary, it seems that the extent and quality of the counmy's ajhii went into a steep decline, with frequent disruption and even total destruction during periods of civil strife. By the time of the Ya'aribah imams, the need for a comprehensive rehabilitation of the country's irrigation resource and agricultural base was paramount Culturally, the Ya'aribah dynasty is an interesting period, arguably the 6rst Golden Age of the Omani state and a time when the arts and agriculture alike flourished. There were developments of great architectural significance, such as the comprehensive redesigning and and expansion of towns such as Nazwa, al &m~%' Birkat al Mawz, and the construction of many of Oman's celebrated form. The majority of Oman's most significant historic buildings date from this period. The basis for such cultural and material prosperity was the relative peace and security brought about by the rule of the m imams. This in t n provided the opportunity to rescue and rehabilitate the counuy's d i g ajhii, thereby providing the means to expand the country's agricultural base. Many sFsj were rebuilt, but there is no evidence to suggest that any completely new systems were constructed. Indeed, it is possible that by this time the knowledge and skills to do so had disappeared?' m In the case of the a ,the role of master-builder is filled by the ' A w e mbe. Wilkinson has documented how and when this group arrived in Oman and how they subsequentlyspread across the land, restoring neglected @ a and defunct? so that the fields could be brought back into production." To this day the ' A w e retain something of a monopoly on the skills required to maintain and service the network, but as socio-economic expectations and lifestyle patterns change, so these ancient skills are dwindling.

Settlement Patterns

Considerable study has been conducted into the origin and development of traditional settlements in Oman.'* These can be summarized as being of two basic types; coastal and interior. As far as the latter is concerned, the most frequent pattern is for an oasis setdement to develop at a point where water and cultivable land coincide. Fertile soil is almost as rare, if not rarer, in Oman than fresh water and a location blessed with the presence of both is an enviable spot indeed. Itwas therefore necessary to defend such sites from covetous neighbours and so settlements were generally located on the nearest high ground (usually a rocky outcrop), with the cultivated fields spread out around and below. The elevated position of the houses allowed psychological and physical domination of the site, as well as some degree of protection in the event of flash floods. The vast majority of the interior settlements of Oman mirror this pattern.

Derelict hama rn T d f i shmvingbd&q mom h i l f o w the f&l

44

THE A R C H I T E C T U R E O F O M A N

At locations where water and dtivable soil did not coincide, then it was often possible to bring the water to the fields by means of afilaj. Even when the two core commodities were naturally present in the same place, there was often the need to fashion and develop them m suit the needs of the local population. The aF.3 system played a key role in thisprocess also. In most cases, water is imported to the cultivable land by the & The channels may stretch for many kilomeues and be derived &om different sources, so the final convergence can be quite complex. Often the point of arrival of the water supply was found to be too far below the field level, in which case large-scale excavations were required to reduce the ground level accordingly. The huge spoilheaps this created, known as d d (sing. &), are clearIy discernible in many Omani settlements and were often used to form raised banks between the individual fields or gardens. The nzufd are as much a part of the loc&~pgraphy and architecture as the buildings which hl*.aften been consuucted upon them and conmbute to the?upstairs-downstairs' character of many Omani settlements, whereby the residential quarters occupy the high ground, from which the inhabitants descend to tend their fields below. Except where local topography made it impossible, a settlementwould be ranged alongside thef channels & before these descended to the imgation areas. This

avoided problems in transportingwater m the home and allowed a degree of domestic comfort. For example, the seventeenth-centuryrehabilitation of the & and town a3 j of a1 Ha-' involved the consuuction of some of the grander houses with their frontage actually over thefihzj, to allow for rooms in whicb bathing could be carried out pri~ately.'~ Similar houses (now ruinous) can be seen at Tantxf. Equally, the forts of Jabrin and Bayt a1 Rudaydah in Birkat al Mawz were each sewed by afalaj running straight through the centre of the building. That at Jabrin is now dry, but thef&j Bitkat alMawz remains of in good condition. The centrality of water in Oman, and the key role played by the afi3 in its procurement and distribution, has resulted in the latter often serving as a broker and vehicle for peace in times of dispute. Intemibal rivalries and feuding had to be periodically set aside due to mutual dependence on a shared water supply. Nowhere is this more evident than in Izki, a classic oasis settlement served by one of the greatest afi3 of all, al Malki. Comprised of two historically distinct and traditionally antagonistic settlements- al N b and al Yarnan - Ik depended on a unified irrigation system. Despite zi the frequent strife between the two warring quarters, t e were compelled to cooperate on the maintenance of hy thefalaj system, which provided the basic means of subsistence for all villagers. It also financed communal institutions, such as the nrp,mosque and waqfeducation trusts, through money raised b m selling shares in the imgation cycle. As in many settlements, the arrangements for administering and distributing water in I k were zi complex. The network in general was under the responsibility of a communal ajl@administration, with individual owners responsible for the upkeep of channels in their own fields. Each plot of land had a prescribed -pcxJd%f irrigation time, whicb formed part of a larger cycle covering the whole area. Channels were opened and closed according to the cycle, this normally being done by simply blocking or diverting the flow with rocks and rags. Shares in the cycle could be bought and sold and, although land and water rights are technically separate in Oman, the right to use water was always

M U S C A T : T R A D I T I O N A L C I T Y A N D GREATER C A P I T A L

57

ospowc A &

ssafraat view amas Muscat bay S 8

QA h P a l m ' I

vinv of ffie dd dn/ of Mucat with Ialciii Fort in he fwrgmund

ntil 1970, Muxat and the rest of Oman were virtually separate entities; Muscat (Masqat) and M u ~ a btwo miles to the west, were geographically and , historically severed from the mainland, two isolated enclaves on the rugged coastline. Inhabitants leaving the coast for the interior would say that they were 'going to Oman'. Architecturally, Muscat and the rest of the towns of the Sultanateshared the cluster form characteristicof the urban settlements of Arabia and North Africa: walls surrounding cities and some towns, and an architectural fabric constructed in local materials restricted to a maxmum of three storeys in height (sometimes four in the case of distinguished town palaces and mansions). Socioeconomic life was centred around settled mbal communities engaged in a combination of fishing, trade, agriculture and grazing, according to the location and historic links of each settlement. The accession of His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Sa'id bin Taymur a1 BaSa'rdr marked the beginning of the modem era in Oman. With the aim of uniting the

country, he embarked on an extensive programme of infrastmcturalrenewal and urban development ofwhich Muscat, the capital, was naturally a focus. During the &st phase two practices, John R. Harris, M t e c t s , Design & Planning Consultants, and Makiya Associates, were each commissioned to prepare a planning proposal for the development and extension of Muscat and neighbouringMud. Harris, a British architect, had established a presence in Muscat in 1965 and was responsible for the 6rst major modem building in the country.' Mohamed Makiya opened his architectural and planning consultan7 practice in Baghdad in 1946, and by the early sixties had established a distinctive style ofmodem architecture based on research into Arab and Islamic architectural concepts. In 1971he set np a design centre in Muscat, and a London oflice followed in 1974. The reports prepared by Harris and Makiya appeared within three years of each other (in 1970 and 1973 respectively) and had similar fundamental aims: to d e h e the status and role of the old city ofMuscat in the

J

-

50

THE ARCHITECTURE O F

OMAN

Top l d t

The rertoredlalali F o , one of M w d s two defenriveg&som, hrderin8 the old cify to the east

Above

The restored Krani Fort, whrch protected M m t porn n c m bysw to the west

TOPri!&t

The old city of Muscor, Iwkingsorrth

Bettot" right Aerial YMY of the MuQoh coactal strip

context of national politics and economics; to preserve the walls and traditional buildings of the old city; to set out guidelines for buildings in the new dismcts; and to propose plans for the expanding metropolitan region. Both Hams and Makiya emphasised the importance of preserving the cultural heritage of Muscat while allowing for urban development and expansion. Each suggested a different means of achieving this. Makiya Associates defined Muscat as a cul-de-sac city, an enclave of historic building that should be kept intact. Their report empbasised the tremendous national value of Muscat's heritage, which they recommended should be enriched by maintenance and renovation and safeguarded against the onslaught of development. In order to retain the city's unique characteristics and original identity, they proposed resmcting its function to that of nominal capital city and relocating the state adminisnative departments to the greater metropolitan area then being developed. Makiya's approach was inspired by the

M U S C A T : T R A D I T I O N A L C l T V A N D GREATER C A P I T A L

I9

urban and cultural values of Islamic cities, which are not segregated into public and private districts, and was governed by his desire to integrate the old town's fabricinto any modemising scheme. A two-volume research document entitled 'Muscat City Planning' included a study of Muscat's architectural character, examining in depth its architectural details, historic monuments and public buildings including mosques, the stip, city walls and gates: The report by John R. Harris Architects remained open to a number of different development options. They considered the possibility ofMuscat continuing as the seat of government, and perhaps 'coupled with its role as capital pecoming] a cultural centre . . . [with] commercial development. . .severely restricted'. In tbis scenario, the old city of Muscat would be devoted largely to public builLZlngs and residences for the elite. On the other hand, a new capital might be established elsewhere, in which case they proposed that old Muscat and the neighbonring area of Si&b, on the bay, be developed as a tourist centre, retaining 'as many of the attractive older buildings as is possible' and necessitating 'considerable and sympathetic renovation' - though he also suggested that 'the larger ones could be incorporated into hotels'.' Social and cultural issues formed the basis of both architects' proposals. Improvements in the standards of health, education and public services needed to be accommodated, along with provision for cars and parki g improved electricity, drainage and water supplies, n, and housing for a larger and wealthier population - aII without destroying the indigenous architecture. In order to preserve Muscat aty centre as apredominantlypedestrian area, Ma * ~ r o ~ o s the consrmcdon of a civic ed my&n (square) just outside the south wall of the city. Easily accessible by car and bus, the new m r r y h would operate as amulti-purpose forum for social, sporting and religious functions. Instead of extendingthe city or constructing new housing within its walls, Makiya recommended that the expanding population, which was predicted to rise from 17,000 to 35,000, should be housedinneighbouring areas m the west ofMuscat such as Rum. In this way, the human scale of the city's architecture, as vita1 to its character as its pedestrian streets, could be maintained.

Tor rttc upawiar qM~nIry, Orsafer U1r!r4 in the kctsbm4 mtk

.I

. I nu-,, I : ,

60

THE ARCHITECTURE O F O M A N

- -

'

TOP

T m plan of Mugoh

Above

T o w plon of the old city in Muscat

Opporlte

Grindlny's &mX just G e r complerion

Hams went one step further, proposing that Mugah be extended south and west into the valley hom Ruwi to Darsayt This proposed development site, which he called 'Greater M u d , would become the commercial centre of the entire area, with a new town centre of public and community buildings located at Bayt a1 Falaj, an old fortified palace at the northern end of the Ruwi plain. Harris's proposals for new building were primarily designed according to the demands of modem urban development. Though he acknowledged the importance of traditional spatial organisation in his proposals for three schemes of dwelling units - courtyard core housing, low-cost housing and housing over shops - the plans did not fully consider the nuances embedded in the overall structure of the old city fabric. The expression was linear in form and the repetition of the units somewhat predictable. Nonetheless, within the parameters of modern construction and design Harris succeeded in interpreting the social values and traditional elements of Arab architecture in a new yet sympathetic form. Both proposals envisaged the creation of a network of roads to senrice the new areas and separate them from . the old walled towns of Muscat and M u ~ a hHowever, while Hams did not object to the ribbon development that would naturally spring up along these roads, Makiya Associates wanted to encourage cluster development, which they felt would stimulate a stronger sense of community and cultural identity for those living outside the city centres. architectural practices wished to preserve and @th vernacular features of Omani building while enc gmg a more contemporary approach, a modern interpretation of the traditional. They both recommended that the planning authorities should be empowered to control future construction through building regulations. Harris provided a general list that included basic zoning, building lines, car parking provision, structural stability, thermal insnlation, soil drainage and room height. Makiya Associates were more specific and produced a thorough list of specifications for new building which included regulations for total height restrictions, use of local materials, design which would take social and hygiene considerations into account, and

M U S C A T T R A D I T I O N A L C I T Y A N D GREATER C A P I T A L

61

guidelines for property layouts so as to incorporate the traditional comtyard element into private housing and to allow fm adequate space between buildings. Neither Harris's nor Makiya's proposals were carried out to the letter, but they undoubtedly influenced the direction taken by the Diwan of the Royal C o w and the municipalities' planning departments. In addition, both practiceswere responsible for the constmctian or renovation of a number of important buildings, landmarks in the development of Muscat and its environs. John Harris had experimentedw t modem ih materials before any planning resmctions existed in Oman. Among the first buildings he designed was the Ottoman Bank (later known as Grindlay's Bank), the 6rst reinforced concrete snucnue in Oman, completed in 1968.The firm had to arrange for Oinan's fitst shipment of sulphate-resisting cement and reinforcing steel, an occasion recorded by k E.Jones, Harris's resident partner in Oman for twelve years: T h e arrival of the ship in M u d harbour caused mch a s t i that senior govern~

ment officials actually attended on the quayside."The bank building was well received because it acknowledged traditional Omani design, incorporating such architectural features as the intricate wooden screened balcony (derived from the traditional Arab mmbsab@yab)and the pointed arch, yet it had a uniquely modem identity symbolic of Oman's new function as a centre of commerce. In the John Harris brochure it is cited as 'an example of a well-mannered building which respects its distinguished neighbours'. Built just outside the main gate which leads into the centre of old Muscat, the bank is an interesting example of a carefully designed modern building in an area of traditional buildings of greater architectural impomce. Hatris describes the principal design consideration of the Ottoman Bank as climatic: heat, light and thermal movement were signijicantfacto~~. 'upside-down' 0s An roof, combinedwith a sun shade above a freely ventilated air space, provided i d a t i o n firom the outside heat. As seasonal rainfall is frequent but heavy, floodwater

64

THE ARCHITECTURE O F O M A N

gargoyles were incorporated and used to punctuate the fagade. The external rendering is simple, since stability was of prime importance in view of the high levels of humidity and salinity in the Muscat air. Among Hams's other buildings are the &st girls' school in Muscat, al Nahda hospital, low-cost bachelor flats, the Omani Tribal School, a clinic at Hayma, the English School, twostorey housing at al Qunn and a -number of commercial buildings. In 1972 he undertook .-the renovation of one of the vernacular buildings in M u d , a house locally known as Bayt Barandi or Bayt Nasib. Other public buildings constructed by the Harris practice include the main post office and government administrative offices, a terminal at Al Sib International Airport and the national headquarters for the Development Council of Oman. Hams's new building

for the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour, completed in 1991 on a prominent site at A1 Khuwayr adjacent to the diplomatic quarter and the avenue of minisma, was the winning design in an architectural competition. Its s t r u c d reinforced concreteframe, which projects two metres &omthe face of the building, is described as 'providing additional solar shielding to the main glazed aes: The pointed arches that take up the height of the ra' fagade reflect the more elaborate style that the practice adopted in its later years, characteristic of a new wave of modemising Islamic architecturalforms. Mohamed Makiya's important projects in Muscat include the renovation of Bayt a1Jrayzah (1976),Bayt al Khajiyyah (1977) and Bab Waljat (1974), one of h e a t y gates of old Muscat. He also designed the new Minishy of Finance, Bayt a1 M&+, completed in 1977."

MUSCAT TRADITIONAL CITY A N D GREATER CAPITAL

65

Abore

M d i y o A s ~ ~ i ( ~ t e ' p r . $ pfor stredFcape below the a t e m elmm.On of s~I MiraniFmt,1972-1973; al Khmvr Mosque and Bnyt 111 /myurh are on the exbeme risht immed~ately below the forZ

blow

DetoiI of ~1d w r in Bnyt ol m-ryyzh, Muscat, pen nndink drmving By Sarah White. 1995

Standing just outside Bsb Waljat, Bay a1 Mtlliyyah is constructed out of stone, both in keeping with the architecture of the old city and appropriate for t i largehs scale, impressive building. Makiya felt that it was better to construct this new building outside the old city rather than within the walls, where it would have had to conform to the scale of the surrounding vernacular buildings. However, the architect adds, 'I nevertheless wanted to maintain a civic s a l e in this complex, as it is visible from the old city wall and should not impose on the horizon.' Most recently, Makiya served as principal design consultant to the winning scheme by architects Quad Design for the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque competition in 1993.

A Philosophy for BudThe Modem Interpretation of the Vernacular

Mohamed Makiya considers that the best way to conserve the traditional urban fabric is to establish 'a vocabulary of design' which would include all the elements such as windows and arches. 'It would be very simple,' he said wheninterviewed in October 1996, 'and it would encourage people to commission and execute

66

THE ARCHITECTURE OF OMAN

TOP Va1l.m in SMb' d Qunn

Above

their own restorations.' His idea is to teach local craftsmen 'to build in the original vernacular style, and to supply them with facilities and reasonably priced materials so that they can reconstruct their own villages': Makiya gave three conferences and set up an exhibition in Muscat to explain his approach. 'I suggested that the municipality should provide workshops that would produce windows, doors, toilet facilities, etc., to blueprint designs at a non-profit price. Local craftsmen could then incorporate these pre-cast units and this standard of design in new building.' Makrya's philosophy is that 'building comes out of the people and the environment, rather than out of the often unsympathetic, academicapproach that architects tend to employ. That is why I spent so much time researching the traditional architecture of the area and building up my own knowledge of local techniques, materials and designs.' Though he did recommend planning regulations to resmct building height and ensure the use of vernacular styles, Makiya considered his methodology of conservation quite unusual in that he sought to disseminate his ideas rather than provide a 'set text' of instructions or regulations. Hard and fast rules would, he felt, only be restrictive and stifle the diversity of Omani cities, where higher- and lower-income districts are constructed of different materials and have simpler or more elaborate design features. He took as an example the Egyptian architect Hasan Fathy, who established a school of thought based on the design concepts of Islamic and vernacular architecture, the use of local building materials and the traditional techniques of master builders: 'There's a background to his work, and its beauty is unsurpassed. In order to appreciate these buildings we have to see them, learn to look at them and then measure their spaces. Once you have done this, you find that you are bound to be intluenced by the void and the volumes and the interplay between the two.' Makiya hoped that the restorations he undertook 'would be used as case studies and that people would look and learn from them'; they could, he felt, serve as examples for restoration and design in the future.

Vzlla promtgpe tn Shiv a1 Qunn, based on the rnunicipalcty's regulnhons

M U S C A T T R A D I T I O N A L C I T Y A N D GREATER C A P I T A L

67

Modem Development

The 1980s saw an increase in construction so rapid that the preservation of Oman's architectural heritage was threatened. Consequently, the Ministry of Land Affairs (subsequentlythe Minisay of Housing) issued instructions requiring new building to comply with prescribed 'Islamic' forms. In k E. Jones's opinion the regulations were too extreme, consisting of 'fairly arbitrary requirements for castellations on building parapets, gotbic and curved arches over windows and a general referral to a type of building which never r e d y ead~ted'.~ The Development Council and Daimler-Benz service buildings, which were built according to the stringent new regulations, show little synergy between the old style and the new materials; the use of castellation, in particular, is redundant at best. Also in the spirit of the new regulations, a proposal was made for the 'beautification' of the National Bank of Oman, which had been built by a German h u s i n g an imported prefabricated profiled cladding system. This was never carried out due to the expense it would involve. k E. Jones reports that 'a direct consequence of this was a resolution that no further "modem" buildings would receive Municipahty approval, and tbis effectivelymeant an end to anti-solar glazing, metal cladding and postmodernist treatments of buildings which reflected available technology.'' Since the early 1990s, however, several new buildings have again employed postmodernist features and modem glazing, within the prescribed criteria for the 'modern vernacular'. In 1987 'Elevational Guidelines for Shatj' al Qurm Area' were produced by the Diwan of the Royal Court. The objective of this document, commonly referred to as the pink He by architects practising in Muscat, was 'to ensure the high quality of architectural design, in the modem and unique Arab/Omani and Islamic architecturalstyle, while using modem buildmg materials; and to establish the origins of cultural values in contemporary Arab architecture by acknowledging the Arab and Islamic social values in architect~re."~ Although the intentions of the manual were irreproachable, the accompanyingillustrationswere restrictive and thin. Sets of drawings, under the beading of elevation control, specified the form and style of boundary walls and gates, main enay doors (giving options for arched or flat lintels), railings and motifs in solid wood and perforated w d panels, roof parapets using screens and perforated panels in concrete rendering and wood, screens and enclosures to create privacy and conceal modem installations such as air-conditioningunits, and balconies with instructions for screening where they faced neighbours or were used for drying clothes. A sheet on the appropriate method of constructing arches included ten types of pointed, segmental and one semicircular arch. A section on window detailing (which employs aluminium-framed glass windows) suggests ornamental relief panels emulating stucco-workin decorative wooden masbrabiyyab or 'arabesque' patterns, and louvres; only an Indian pointed arch and a semicircular arch are shown. Finally, elevations of four different villas are used to illustrate exterior w d treatments, indicating the types of masonry to be used: concrete block-work or Omani calcium silicate bricks, with only 'very limited use' of stone, granite and marble. The type of paint is specified, and more importantly the colours to be used for exterior walls: white, light buff and silver grey. Despite the shortcomings of its creative standards, the manual succeeded in controlling the chaotic development that occurs in every rapidly developing city. The guidelines were implemented in d the new dismcs l including residential areas like Madinat Qaboos and Shsg a1 Qurm, which are in general exceptionally well-organised with a number of interesting and welldesigned buildings. The houses are restricted in height to three storeys, and are generally painted white with a limited number of screened windows. There are coloured windowpanes, carved Omani-style doors, and decorative perforations and cast relief panels in repetitive patterns. The few aesthetically jarring buildings are faulty in terms of detailing rather than structurally. Overall, the housing is representative of an unobtrusive style that evolved characteristic of new development, unprecedented in the Gulf region in its orderliness and respect for tradition.

You might also like

- Basics Freehand DrawingDocument96 pagesBasics Freehand DrawingÎsmaîl Îbrahîm Silêman100% (7)

- Western ArchitectureDocument388 pagesWestern ArchitectureFran Hrzic100% (8)

- Wbs and Division of Work Excel Spread Sheet1Document12 pagesWbs and Division of Work Excel Spread Sheet1Adrian Christian Lee100% (1)

- AAC Made Easy: Intro to Autoclaved Aerated ConcreteDocument53 pagesAAC Made Easy: Intro to Autoclaved Aerated Concreteluigi firmalinoNo ratings yet

- Architecture ClassicDocument24 pagesArchitecture ClassicYopi Andrianto100% (4)

- Waterproofing Applications: Established in 1959Document16 pagesWaterproofing Applications: Established in 1959Chesca DacquelNo ratings yet

- Islamic Art and ArchitectureDocument292 pagesIslamic Art and ArchitectureArkona100% (5)

- Iraq ArchitectureDocument58 pagesIraq ArchitectureJuan Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Introduction To Column Shortening Analysis - Case Study of Lotte TowerDocument71 pagesIntroduction To Column Shortening Analysis - Case Study of Lotte TowerAlden CayagaNo ratings yet

- Wheat Ridge-ASDM - Rev 2017 - 201709140930401804 PDFDocument43 pagesWheat Ridge-ASDM - Rev 2017 - 201709140930401804 PDFRavy KimNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Use of The Existing Buildings inDocument28 pagesOttoman Use of The Existing Buildings insearching1_2No ratings yet

- Modern Architecture of HelsinkiDocument124 pagesModern Architecture of Helsinkimetrowave100% (9)

- Aedas Portfolio (Copyright Aedas)Document50 pagesAedas Portfolio (Copyright Aedas)arjun_menon_650% (2)

- E3 Internal Moisture Amendment 5Document22 pagesE3 Internal Moisture Amendment 5Sam LeungNo ratings yet

- Architectural Representation of IslamDocument417 pagesArchitectural Representation of IslamMuhammad Abubakar AhmadNo ratings yet

- History of PlanningDocument28 pagesHistory of PlanningLouise Lane100% (1)

- Ancient Greek ArchitectureDocument60 pagesAncient Greek Architecturenenna100% (2)

- Architecture: M. Ryan Academic Decathlon 2005-06Document21 pagesArchitecture: M. Ryan Academic Decathlon 2005-06Tauseef Ahmad50% (2)

- Temporary Structures GuideDocument27 pagesTemporary Structures GuideKaushikJainNo ratings yet

- Architecture: Spotters GuideDocument37 pagesArchitecture: Spotters GuideSarabandBooks100% (2)

- Strongholds of HeritageDocument9 pagesStrongholds of Heritageusman zafarNo ratings yet

- History of ArchitectureDocument656 pagesHistory of ArchitectureAlexandru NenciuNo ratings yet

- Rural and Urban Vernacula PDFDocument6 pagesRural and Urban Vernacula PDFFarhan Giano IndrakesumaNo ratings yet

- Competition - Brief BETON HALA PDFDocument18 pagesCompetition - Brief BETON HALA PDFarchpavlovicNo ratings yet

- The Power of Buildings, 1920-1950: A Master Draftsman's RecordFrom EverandThe Power of Buildings, 1920-1950: A Master Draftsman's RecordNo ratings yet

- Live Work Stay PlayDocument60 pagesLive Work Stay PlayCOXNo ratings yet

- Omani Architecture During The Petroleum EraDocument108 pagesOmani Architecture During The Petroleum EraSomeone Orather100% (1)

- Greek ArchitectureDocument162 pagesGreek ArchitectureAbhishek Sharma100% (1)

- Marrakech - The Forgetting of AirDocument49 pagesMarrakech - The Forgetting of AirSasha Nash100% (1)

- The Radiant City by Le Corbusier 1964.OCRDocument290 pagesThe Radiant City by Le Corbusier 1964.OCRAmine Somerville100% (1)

- Jan Wium - PrecastDocument25 pagesJan Wium - PrecastTino MatsvayiNo ratings yet

- Geoffrey BawaDocument151 pagesGeoffrey BawaFarhain Mohd YusriNo ratings yet

- Architecture Education in The Islamic WorldDocument232 pagesArchitecture Education in The Islamic WorldMihaela20073100% (1)

- PLANNING 2 FUNDAMENTALSDocument29 pagesPLANNING 2 FUNDAMENTALSnads aldoverNo ratings yet

- Ideas That Shaped BuildingsDocument373 pagesIdeas That Shaped BuildingsLiana Wahyudi100% (13)

- Model Estimate For Hume Pipe Culvert Dia - 600 MMDocument6 pagesModel Estimate For Hume Pipe Culvert Dia - 600 MMNirmal Singh AdhikariNo ratings yet

- Bosnia Dwelling TraditionDocument8 pagesBosnia Dwelling TraditionTaktinfoNo ratings yet

- Traditional Mediterranean ArchitectureDocument99 pagesTraditional Mediterranean ArchitectureIrma ŠantićNo ratings yet

- Rasembadran 12834093196204 Phpapp02Document15 pagesRasembadran 12834093196204 Phpapp02rohan_murdeshwarNo ratings yet

- Culture and ContextDocument13 pagesCulture and ContextLidhya Teslin JosephNo ratings yet

- Week1 PunctuationDocument4 pagesWeek1 PunctuationJel AllendeNo ratings yet

- Architecture Portfolio Jose Maria UrbiolaDocument16 pagesArchitecture Portfolio Jose Maria UrbiolajubarberenaNo ratings yet

- 1507 - in Search of An Ottoman Landscape' - Sinan's Works in T Hrace As Expression of Tangible Heritage - Luca ORLANDIDocument10 pages1507 - in Search of An Ottoman Landscape' - Sinan's Works in T Hrace As Expression of Tangible Heritage - Luca ORLANDIAHZeidanNo ratings yet

- Mocha - Maritime Architecture On Yemen - S Red Sea Coast. - in - ArchDocument14 pagesMocha - Maritime Architecture On Yemen - S Red Sea Coast. - in - ArchDoaa essamNo ratings yet

- HUMANITIES - URBANIZATION IN OMAN SINCE 1970SDocument5 pagesHUMANITIES - URBANIZATION IN OMAN SINCE 1970Spratik bapechaNo ratings yet

- The Historic FabricDocument8 pagesThe Historic FabricMilena ShundovskaNo ratings yet

- Nablus City My PlaceDocument24 pagesNablus City My PlaceMay SayrafiNo ratings yet

- Razvoj Grada Sarajevo EngleskiDocument16 pagesRazvoj Grada Sarajevo EngleskiMugdim BublinNo ratings yet

- Acsa Am 99 99 PDFDocument10 pagesAcsa Am 99 99 PDFKushal2187No ratings yet

- 173 RevDocument131 pages173 Revmomo177sasaNo ratings yet

- 385Document10 pages385Ahmed RamziNo ratings yet

- Sana'a in YemenDocument113 pagesSana'a in YemenTiyyara Comercio IslámicoNo ratings yet

- Revival of Cultural Heritage: The Case Study of The Ottoman Village in Umm QaisDocument18 pagesRevival of Cultural Heritage: The Case Study of The Ottoman Village in Umm QaisShadan MuNo ratings yet

- More Information: Cities, Imagination, and Memory in The Ancient Near EastDocument10 pagesMore Information: Cities, Imagination, and Memory in The Ancient Near EastsrdjanNo ratings yet

- Amber RoadDocument4 pagesAmber RoadvedantNo ratings yet

- The-Urban-Space-Of-The-Turko-Balkan-City - Content File PDFDocument8 pagesThe-Urban-Space-Of-The-Turko-Balkan-City - Content File PDFVasilis KostovassilisNo ratings yet

- Regional Identity, Tradition and ModernityDocument3 pagesRegional Identity, Tradition and ModernityAnas AlomaimNo ratings yet

- Port Cities Multicultural Emporiums of ADocument113 pagesPort Cities Multicultural Emporiums of Ahaikal muammarNo ratings yet

- Melaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of MalaccaDocument4 pagesMelaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of MalaccaAnggihsiyahNo ratings yet

- A Portrait of The Ottoman CitiesDocument41 pagesA Portrait of The Ottoman CitiesourbookNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia's Red Sea Coast - 2017Document20 pagesSaudi Arabia's Red Sea Coast - 2017gescobarg4377No ratings yet

- Master BookDocument315 pagesMaster BookFreddyWinataNo ratings yet

- Oman Across Ages MuseumDocument2 pagesOman Across Ages MuseumjNo ratings yet

- SHEDET Volume 7 Issue 7 Pages 184-200Document17 pagesSHEDET Volume 7 Issue 7 Pages 184-200Seyfettin SaricNo ratings yet

- History of Silk TradeDocument7 pagesHistory of Silk TradePARI PATELNo ratings yet

- Moroccan Riads in The Context of The Development of Modern Tourism in UkraineDocument13 pagesMoroccan Riads in The Context of The Development of Modern Tourism in UkraineInforma.azNo ratings yet

- Social Economic Profile of Kilwa DistrictDocument29 pagesSocial Economic Profile of Kilwa DistrictAlmas Kashindye100% (3)

- Stone Agra CraftDocument3 pagesStone Agra CraftDauha FaridiNo ratings yet

- Preservation and Development of Islamic Architectural Heritage in Central AsiaDocument9 pagesPreservation and Development of Islamic Architectural Heritage in Central AsiaarhfareNo ratings yet

- Crafts of Sarajevo - Keepers of Baščaršija TraditionsDocument8 pagesCrafts of Sarajevo - Keepers of Baščaršija TraditionsdexNo ratings yet

- From Oasis to Global Stage: The Evolution of Arab CivilizationFrom EverandFrom Oasis to Global Stage: The Evolution of Arab CivilizationNo ratings yet

- Isoking Glasswool BoardDocument6 pagesIsoking Glasswool BoardWaruna PasanNo ratings yet

- Assembly Instructions Pent ShedsDocument1 pageAssembly Instructions Pent ShedsbarryNo ratings yet

- SlenderWall 2021 Brochure WEBDocument5 pagesSlenderWall 2021 Brochure WEBAdriana WaltersNo ratings yet

- ASTM Brick Standards GuideDocument19 pagesASTM Brick Standards GuideRocel Mae PalianaNo ratings yet

- PantheonDocument1 pagePantheonShirley DasNo ratings yet

- Greek and Roman ArchitectureDocument72 pagesGreek and Roman ArchitectureChiara Mata IgnacioNo ratings yet

- BTN 2012-002 v1.1 Bonded AnchorsDocument3 pagesBTN 2012-002 v1.1 Bonded Anchorsaeroforce1007No ratings yet

- Product Catalogue 2021 20210303Document64 pagesProduct Catalogue 2021 20210303leeNo ratings yet

- 10908Document305 pages10908loginxscribdNo ratings yet

- Fire Safety Requirements For PlasticsDocument11 pagesFire Safety Requirements For PlasticsAzmi NordinNo ratings yet

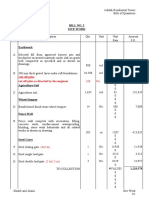

- Bill No. 2 Site Work: December 2008 Jeddah Residential Tower Bills of QuantitiesDocument10 pagesBill No. 2 Site Work: December 2008 Jeddah Residential Tower Bills of QuantitiesJohn Paul PagsolinganNo ratings yet

- Ferromortar 707: Iron Fortified Non-Shrink Grout For Dry-Pack To Pourable InstallationDocument2 pagesFerromortar 707: Iron Fortified Non-Shrink Grout For Dry-Pack To Pourable InstallationFrancois-No ratings yet

- FT-Flume: FUJI Precast Concrete SolutionDocument4 pagesFT-Flume: FUJI Precast Concrete SolutionshreyashNo ratings yet

- Colonial ArchitectureDocument20 pagesColonial ArchitectureNandini SNo ratings yet

- Tek 14-13BDocument5 pagesTek 14-13BCory LarkinNo ratings yet

- Re100 - Hindu-And-Indian-Architecture-Sta CruzDocument37 pagesRe100 - Hindu-And-Indian-Architecture-Sta Cruzalex medinaNo ratings yet

- Change of Direction: Mr. & Mrs. Sire Henrik Andersson As-Built 3 - Storey Residential BuildingDocument1 pageChange of Direction: Mr. & Mrs. Sire Henrik Andersson As-Built 3 - Storey Residential BuildingChrysler DuasoNo ratings yet

- Type Inserts With Hole: WNMG 08 04 04-FHDocument4 pagesType Inserts With Hole: WNMG 08 04 04-FHTungstenCarbideNo ratings yet