Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Raj Rewal Asia Games Housing

Uploaded by

Shubh Cheema60%(5)60% found this document useful (5 votes)

3K views8 pagesHousing complex consists of 700 dwelling units and a mix of recreational and commercial facilities. Located near the medieval ruins if Sid fort in south Delhi, 35 acres were allotted by the Delhi Development Authority for 700 housing units. The project took just under two years to build.

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHousing complex consists of 700 dwelling units and a mix of recreational and commercial facilities. Located near the medieval ruins if Sid fort in south Delhi, 35 acres were allotted by the Delhi Development Authority for 700 housing units. The project took just under two years to build.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

60%(5)60% found this document useful (5 votes)

3K views8 pagesRaj Rewal Asia Games Housing

Uploaded by

Shubh CheemaHousing complex consists of 700 dwelling units and a mix of recreational and commercial facilities. Located near the medieval ruins if Sid fort in south Delhi, 35 acres were allotted by the Delhi Development Authority for 700 housing units. The project took just under two years to build.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

Project Data

Asian Games Olympic

Village, Delhi, India.

The housing complex consists

of 700 dwelling units and a

mix of recreational and

commercial facilities.

Client: Delhi Development

Authority.

Architects: Raj Rewal

Associates.

Design team headed by Raj

Rewal, with A. Dhar, A.

Jain, V.K.Jain, A. Mathur

and S. Verma.

Structural Engineel': N.F.

Patel.

Landscape Architect:

Mohamed Shaheer

Completion: Octo bel', 1982.

Text by

Hasan Uddin-Khan.

Photographs by Madan

Mahatta. Illustrations

courtesy of the architects.

Asian Games Housing, Delhi

Quite often housing designed for a specific event

becomes a showpiece if contemporary archi-

tecture, perhaps the most famous being Habitat

in Montreal built for Expo-67. Raj Rewal's

housing for the Asian Games held in Delhi in

November 1982 has been designed in the tradi-

tion if such works, but attempts to create a

village to instil a sense of community and

participation in the best spirit if an Olympiad.

Located near the medieval ruins if Sid fort

in South Delhi, 35 acres were allotted by the

Delhi Development Authority (DDA) for

some 700 housing units. The project took just

under two years to build.

H

olding any Olympiad

means the initiation of

many new building pro-

jects for the host nation

. - new stadia, hotels,

visitors facilities and a

whole "village" to house

contestants from the participating countries.

This, requires the mobilisation of resources

in terms of finances, manpower and profes-

sional expertise. The expenditure is signifi-

cant and the buildings constructed for this

massive influx of people are often under

utilised after the event.

With this in mind, the architects de-

signed the olympic village housing to be

used by the local population after the event,

and have given the buildings an Indian

character.

The village has been designed as a sequ-

ence of spaces to create mohallas or neigh-

bourhoods. It parallels efforts by other de-

signers in India to create "urban villages" in

a city. In traditional Indian cities each mohal-

la would be made up of a single social

group, and would vary depending on the

size and resources of that particular group.

Sometimes a minority group, such as the

Muslims, would settle together. In Rewal's

scheme he had no way of knowing how

large a mohalla would actually be and has

designed the clusters to be of various sizes to

have between 12 to 36 houses. Of the total

700 units, 500 are lats.

The flats vary in size, from 90 square

metres to a maximum of200 square metres.

Each unit has its own private open-to-sky

space, in the form of a courtyard or a

terrace, in addition to sharing a larger less

private communal garden area. The house

clusters, with their connecting walkways

and terraces overlooking the intemal pedes-

trian streets or gal is, help give the people of

the mohalla a sense of participation in com-

munal activities.

Unlike westem neighbourhoods, the

sense of actively "keeping an eye" on one's

neighbours and being able to share experi-

ences and conversation with each other is

integral to the creation of community. Re-

wal's scheme takes this into account by the

honeycombing of spaces and by letting the

pedestrian circulation through the wide and

52

narrow galis give access to the houses.

Another defining element in old walled

cities, as in Delhi itself, is the gateway or

darwaza. The separation of space, of mohal-

las, is equally as important as its integration

in letting communities define themselves.

These darwazas were rather grand and

sometimes guarded to keep intruders out of

a particular neighbourhood; especially at

night. With a rather neat twist and use of a

traditional element, the design makes these

darwazas define the spaces, but they do not

actually have closable doors. In fact this

device separates the mohallas at ground level

but creates a walkway which connects two

sides of a gali above the gateway. This may

be visual game-playing, but it is architectu-

ral game-playing at its best.

Too often in contemporary architecture

the symbolic aspects of design are forgot-

ten. Here they manifest themselves in many

different ways; be it the multi-purpose

spaces or the visual elements that give the

scheme a continuity with the past. The

sense of enclosure and continuity of move-

ment is maintained throughout the scheme,

respecting the identity of spaces. The scale

of the buildings and their density (of 28

units per acre) and the mix of public and

commercial spaces, gives the whole village

an intimacy and a humane scale.

There has been a careful selection of

materials and colours for the housing. The

building external walls are finished with a

stone aggregate applied in situ while the

courtyard walls are of Delhi quartzite stone.

Pedestrian pathways are paved with white

or red sandstone. The doors and windows

to the houses are of metal and are painted in

bright colours which also give a sense of

identity to the different units.

In the design, easy maintenance has

been introduced as with the exposed service

ducts. Climate too has played a prominent

role in ordering design, for example the

terrace parapets are perforated as jalis to

allow for air circulation without affecting

the privacy of the inhabitants.

Right: A bi/ds eye view of the Housing Complex,

designed to create a community with its connecting

walkways and honeycombing of spaces.

53

Above: The Asian Carnes housing consists of 500 flats

and 200 town houses, in two to four storey buildings,

having a density of 28 units per acre. The housing

surrounds the present dining complex which will later

be converted into a commercial and residential block.

The buildings are clustered to form mohallas or

neighbourhoods, each with between sixteen and thirty-

six dwellings. A central pedestrian spine, modelled on

traditional galis, interconnects the clusters. Pedestrian and

vehicular access to housing is kept segregated but linked

for convenience. Car parking in cui de sacs is off the

peripheral roads.

Right: The isometric drawing of a typical cluster shows

how the houses are designed as interlocking units,

usually in a block of four to six flats.

Each cluster has its own integrity, being diftned by

large darwazas or doorways, which have been a

feature of old city quarters in northern India. In the

long term, it is hoped that each cluster will develop its

own identity.

The houses and roof terraces often overlook the

streets (galis) and the communal courtyards, creating a

sense of participation among residents, in what the

architect calls "the theatre of the street."

54

1-

block ojjou,

apartments

group of eig/lt apartments

linked 011 ends

cluster of sixteefl

apartments linked Otl

ends alld front

group oftLVeive apartments

litlked 0/1 ends

cluster of twenty fou r

apartment IiI/ked all ends

alld partly Ol/froll t

,

, ,

L ___________ .J

Type 'E' Housing Type El Ground floor plan

Top: View of one of the interior .coultyards of a type

'E' unit block. The building overhangs provide shade

for the pedestrian pathway. To the rear is one of the

darwazas, which defines the boundary of this small

mohalla.

Above: A typical housing unit block is so designed that .. __ . __ . __ .. 1 ____ .

it can be linked on sides and front to create clusters

having a variety of enclosed spaces.

Right: The Type '' unit rises four stOl'eys and r::, ,-.-_-_.

consists of two duplexflats each having three bedrooms.

r

Type E2 First floor plan

55

Mezzanine floor plan

Second mezzanine floor plan Terrace plan

Type 'A, B and C' Housing

Above: Roof terraces are enclosed by parapets which

have openings to allow for the passage of air. The

service ducts are exposed at pipe joints for easy mainte-

nance and replacement.

Below: Pedestrian pathways, narrow and shaded, are

an important feature of the design.

Right: Metal 'louvered shutters for windows and gates

are painted in d!fferent colours to identify individual

units.

Right, below: A typical gab or pedestrian street with

entrances to the flats through private courtyards.

56

~ l : ~ ~ ~ " ~ ' " ~

"i.::';.: \ : ' ~ ' " . ~ .. ':.'1. /\

57

Type Gl Gmund floor plan

Type G3 Second floor plarl

Type 'G' Housing

Top" Successive couI1yard in a type 'G' block accwtuate

the linear axial planning of the mohallas,

Top, right.' Details o[agatewa),.

Type G2 Fil'St floDl' plan

Thil'd floor plan

Abwe: Type 'G' Housing is four stOl'eys with a three

bedmo111 flat on the grourld floOl', a two bedmom flat all

the first floDl' and a three bedl'Oom duplex unit on the top

two storeys. Each unit has its private open space as a

coU11yard or torace,

58

T

he Asian Games are over

and the village has been

returned into the hands of

the Delhi Development

Authority (DDA) as part

of its housing stock, The

architects have completed

their task of creating an environment which

attempts to foster community by the i n ~

tegration of spaces and the use of symbols

familiar in old Indian cities.

A number of questions, which are im-

portant to the future of DDA public hous-

ing developments, have been raised by this

scheme, Are the costs too high and the

densities too low for such housing to be

replicated on a mass scale? The space stan-

dards of the smaller units may be appropri-

ate, in financial terms, for lower-income

housing, but will the size mix be able to

accommodate social mix? Is such a mix

desirable? Will this design actually help

"create community"? Can the DDA be

sensitive in the allotment of houses, to be

able to sell or rent them to people with

compatable backgrounds, so that there is an

opportunity of their banding together? Or

is that too difficult to do from the Indian

bureaucratic framework? (It is interesting to

note how the Singapore authorities are able

to sell houses on the sanle floor of a

high-rise block to members of extended

families, in order to preserve a sense of

continuity and cohesion,) Once the houses

are occupied, will the public spaces be

maintained: by whom? Will the city be able

to provide services, such as garbage collec-

tion, effectively?

Some of these questions will be

answered in the near future when the alloca-

tion of housing begins, But we will have to

wait for a few years before the reality of the

situation becomes apparent. What is certain

is that the way in which houses are sold or

leased and the way in which maintenance

procedures are institutionalised will either

make, or break, this commendable attempt

at creating community housing.

. & ~ ~

! ! I I 1 ~ 11 I ! J II

rm

lmiII :

."

59

Left: The careful selection if

materials and colours for the

complex is rciflected in the use of

Delhi quartzite stone for the

courtyard walls, white or red

sandstone for pathways and

stone aggregate fir/ish for the

external walls.

Left, below: An 'interior' view

if a mohalla shows the private

courtyards at ground level, the

roof terraces and connecting

walkways .

You might also like

- Sheikh Sarai Housing Complex, New DelhiDocument6 pagesSheikh Sarai Housing Complex, New DelhiIshraha100% (1)

- Raj Rewal - HousingDocument39 pagesRaj Rewal - HousingChristySindhuja100% (4)

- Housing Complex Case Study: Asian Games VillageDocument28 pagesHousing Complex Case Study: Asian Games Villagenadiajmi90% (10)

- 3yqexpv61j PDFDocument28 pages3yqexpv61j PDFtage lampingNo ratings yet

- Raj Rewal Asia Games Housing PDFDocument8 pagesRaj Rewal Asia Games Housing PDFClara Viegas100% (4)

- Asian Games Village at Haus Khaz by Raj RewalDocument18 pagesAsian Games Village at Haus Khaz by Raj RewalGowthaman MaruthamuthuNo ratings yet

- Architect BV DOSHIDocument25 pagesArchitect BV DOSHI9848220992100% (19)

- Asiam Games VillageDocument18 pagesAsiam Games Villageriddhi patel100% (1)

- Raj RewalDocument17 pagesRaj RewalGaurav Chaudhary AligNo ratings yet

- Final PPT Interior Land ScapeDocument2 pagesFinal PPT Interior Land Scapebrijesh varshneyNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Vernacular ArchirectureDocument19 pagesGujarat Vernacular Archirecturec bhavanalakshmi100% (1)

- Zakir Hussain Cooperative Housing FinalDocument14 pagesZakir Hussain Cooperative Housing FinalTanuj Biyani83% (6)

- Housing Case StudyDocument7 pagesHousing Case StudyTwinkleNo ratings yet

- Sheikh Sarai Housing ComplexDocument12 pagesSheikh Sarai Housing ComplexHarshita Singh100% (4)

- Case Study Park of LucknowDocument36 pagesCase Study Park of LucknowSuhas SahaiNo ratings yet

- Tzed Homes: Case StudyDocument10 pagesTzed Homes: Case StudyKunal MathurkarNo ratings yet

- Housing: Case Study On Asian Games VillageDocument28 pagesHousing: Case Study On Asian Games VillageGurnoor SinghNo ratings yet

- 5 ABN AMRO Ahmedabad Case StudyDocument3 pages5 ABN AMRO Ahmedabad Case StudyprathsNo ratings yet

- Aranya Housing Final To Be Submitted PDFDocument37 pagesAranya Housing Final To Be Submitted PDFsucheta100% (4)

- Raj Rewal FinalDocument32 pagesRaj Rewal FinalAnkur GuptaNo ratings yet

- Urban Design Study-Yusuf Sarai MarketDocument17 pagesUrban Design Study-Yusuf Sarai MarketFireSwarmNo ratings yet

- Igbc Green TownshipDocument14 pagesIgbc Green TownshipKabi lanNo ratings yet

- Chandni Chowk Redevelopment PlanDocument9 pagesChandni Chowk Redevelopment PlanAnkit JainNo ratings yet

- Chandigarh LandscapeDocument39 pagesChandigarh LandscapemallikaNo ratings yet

- Bhendi Bazaar Cluster RedevelopmentDocument3 pagesBhendi Bazaar Cluster RedevelopmentAjay WaliaNo ratings yet

- Sabarmati River FrontDocument25 pagesSabarmati River Frontramyadwarapureddi0% (1)

- Elective Iv - Urban Design: Identification and Analysis of Urban Issues and Their SolutionDocument9 pagesElective Iv - Urban Design: Identification and Analysis of Urban Issues and Their SolutionDivyansha JainNo ratings yet

- Final Synopsis, Kathputly ColonyDocument10 pagesFinal Synopsis, Kathputly ColonyFeroze AlamNo ratings yet

- Building Case Study - 30.09.16Document16 pagesBuilding Case Study - 30.09.16Abhishek KadianNo ratings yet

- The City of BhubaneswarDocument3 pagesThe City of BhubaneswarNikiNo ratings yet

- Undergrad Thesis ReportDocument69 pagesUndergrad Thesis ReportChetna Gaurav Chauhan100% (3)

- Case Study Of: Carter Road Waterfront DevelopmentDocument15 pagesCase Study Of: Carter Road Waterfront DevelopmentMUHAMMAD SALMAN RAFI0% (2)

- Housing in India: An OverviewDocument33 pagesHousing in India: An OverviewAjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Allan B. Jocobs (Urban Designer) : Submitted To-Ar. Priya Gupta Ar. Pranshi Jain Submitted by - Surbhi JainDocument12 pagesAllan B. Jocobs (Urban Designer) : Submitted To-Ar. Priya Gupta Ar. Pranshi Jain Submitted by - Surbhi JainkushalNo ratings yet

- Synopsis: Heritage Village (Amritsar)Document7 pagesSynopsis: Heritage Village (Amritsar)ParulDhimanNo ratings yet

- Analysing Chowk As An Urban Public Space A Case of LucknowDocument29 pagesAnalysing Chowk As An Urban Public Space A Case of LucknowAnonymous izrFWiQNo ratings yet

- Thesis Asian Games Village Literature StudyDocument11 pagesThesis Asian Games Village Literature StudyMedha GuptaNo ratings yet

- Auroville (City of Dawn) : Peace AreaDocument18 pagesAuroville (City of Dawn) : Peace AreanidhiNo ratings yet

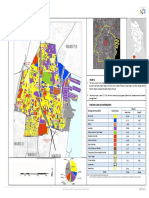

- Magarpatta City: Case StudyDocument5 pagesMagarpatta City: Case StudyKhemrajNo ratings yet

- Uttam C Jain-1Document6 pagesUttam C Jain-1SuryNo ratings yet

- Magarpatta City Ppt1 3Document44 pagesMagarpatta City Ppt1 3bhuse_anil67% (6)

- Belapur CBD Income Tax Colony Housing-HistoryDocument1 pageBelapur CBD Income Tax Colony Housing-HistoryJay DoshiNo ratings yet

- Clarence SteinDocument11 pagesClarence SteinSharda Uppttu KunniparambathuNo ratings yet

- Development and Architecture of NoidaDocument35 pagesDevelopment and Architecture of NoidaDeepak Kumar Singh100% (1)

- PhyInfraRoadsDocument99 pagesPhyInfraRoadsArt BeatsNo ratings yet

- Bangalore Basavanagudi, Bangalore: The Native Town (1537 To 1809) Colonial Period (1809 To 1947)Document2 pagesBangalore Basavanagudi, Bangalore: The Native Town (1537 To 1809) Colonial Period (1809 To 1947)SriNo ratings yet

- Capital PPT - LVLDocument18 pagesCapital PPT - LVLSushmita Mulekar100% (1)

- Who Are Bohras? History and ArchitectureDocument12 pagesWho Are Bohras? History and Architecturearpriyasankar12No ratings yet

- Mumbai - E Ward Level - ELU ReportDocument6 pagesMumbai - E Ward Level - ELU ReportPranay ViraNo ratings yet

- Exploring the Potential of Urban VoidsDocument86 pagesExploring the Potential of Urban VoidsGeetanjali Bhoite ChavanNo ratings yet

- Study of Vernacular Architecture of A International VillageDocument11 pagesStudy of Vernacular Architecture of A International VillageNaitik JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Hall of NationsDocument6 pagesHall of NationsAparna KulshresthaNo ratings yet

- Aranya Housing Case-StudyDocument16 pagesAranya Housing Case-StudyKshipra GajweNo ratings yet

- Belapur - Housing:: A) Project BriefDocument17 pagesBelapur - Housing:: A) Project BriefNaGamani KanDanNo ratings yet

- Asian Games Housing, Delhi: Project DataDocument8 pagesAsian Games Housing, Delhi: Project DataNikhilHemateNo ratings yet

- Affordable Housing in IndiaDocument31 pagesAffordable Housing in Indialavanya thangavel100% (4)

- Raj RewalDocument50 pagesRaj RewalAastha SainiNo ratings yet

- Raj Rewal's masterful design of the Asian Games VillageDocument25 pagesRaj Rewal's masterful design of the Asian Games VillageParvNo ratings yet

- Incremental HousingDocument32 pagesIncremental HousingAjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Precedent Case StudyDocument8 pagesPrecedent Case StudyPriti Shukla0% (1)

- Wadas of Pune: Name: Neha S. Dere Std/Div: Fourth Year/D Subject: Conservation of ArchitectureDocument9 pagesWadas of Pune: Name: Neha S. Dere Std/Div: Fourth Year/D Subject: Conservation of Architectureneha dereNo ratings yet

- Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal: Charles Correa Designed byDocument10 pagesBharat Bhavan, Bhopal: Charles Correa Designed byIndigo CupcakeNo ratings yet

- The Introvert & Exprovert Aspects of The Marathi House PDFDocument20 pagesThe Introvert & Exprovert Aspects of The Marathi House PDFAr Aparna GawadeNo ratings yet

- 103 144851360386 93Document8 pages103 144851360386 93Simran MattuNo ratings yet

- Design Portfolio Sem 3Document34 pagesDesign Portfolio Sem 3kshitij kediaNo ratings yet

- Dharampura Haveli in Old Delhi, India by Spaces Architecs@KaDocument22 pagesDharampura Haveli in Old Delhi, India by Spaces Architecs@KaS.K.SinghNo ratings yet

- French Embassy Staff Quarters: LOCATION: Chanakyapuri, New Delhi, India ARCHITECT: Raj Rewal Construction Period: 1968-69Document9 pagesFrench Embassy Staff Quarters: LOCATION: Chanakyapuri, New Delhi, India ARCHITECT: Raj Rewal Construction Period: 1968-69Ahnaf Nafim ShirajNo ratings yet

- HOUSINGDocument24 pagesHOUSINGAnirudh VijayanNo ratings yet

- JEREMY MORTON ARCHITECTURE PORTFOLIODocument57 pagesJEREMY MORTON ARCHITECTURE PORTFOLIOMichael Ken FurioNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 AgraharamDocument14 pagesUnit 4 Agraharamarchitectfemil6663100% (2)

- Preserving Traditional Architecture in a Proposed Residential PrototypeDocument6 pagesPreserving Traditional Architecture in a Proposed Residential PrototypeSrijana ShresthaNo ratings yet

- THE LEBANESE HOUSE ARCHITECTUREDocument9 pagesTHE LEBANESE HOUSE ARCHITECTUREtamersfeirNo ratings yet

- Housing Typologies 2 of 7 Clusters Groupings and Courtyards PDFDocument7 pagesHousing Typologies 2 of 7 Clusters Groupings and Courtyards PDFanon_823681162No ratings yet

- Charles Correa Housing ProjectsDocument26 pagesCharles Correa Housing ProjectsKshitika ShahNo ratings yet

- Traditional Wisdom & Sustainability Concepts (MSAR215) Assignment 1 - Exploration of morphological aspects of the spatial notionsDocument10 pagesTraditional Wisdom & Sustainability Concepts (MSAR215) Assignment 1 - Exploration of morphological aspects of the spatial notionspoojaNo ratings yet

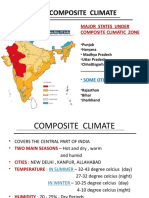

- Major States Under Composite Climate ZoneDocument25 pagesMajor States Under Composite Climate ZoneSporty Game100% (1)

- Types of Housing Form and Year of ConstructionDocument8 pagesTypes of Housing Form and Year of ConstructionKishan SutharNo ratings yet

- Ceiba House, Mexico: Dance Hall With Courtyard Nearby. Spiral StaircaseDocument1 pageCeiba House, Mexico: Dance Hall With Courtyard Nearby. Spiral StaircaseRanjan MadhuNo ratings yet

- HTTP Architecture - Knoji.com The Architecture of The Traditional Arab HouseDocument33 pagesHTTP Architecture - Knoji.com The Architecture of The Traditional Arab Housejaym43No ratings yet

- Design Rakshita PortfolioDocument24 pagesDesign Rakshita PortfolioRakshita GautamNo ratings yet

- Traditional House in JharkhandDocument11 pagesTraditional House in JharkhandYoga LakshmiNo ratings yet

- 1p PinwheelDocument2 pages1p PinwheelwallyTerribleNo ratings yet

- 4-Massing & Orientation For CoolingDocument3 pages4-Massing & Orientation For CoolingaomareltayebNo ratings yet

- Hasan FathyDocument30 pagesHasan FathyShee JaNo ratings yet

- Arkerryhill PDFDocument2 pagesArkerryhill PDFVuTienAnNo ratings yet

- Climatological Factors in Residential PLDocument62 pagesClimatological Factors in Residential PLthabisNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Building Climatology - Chapter 11 - Design in The Zones OCR PDFDocument13 pagesIntroduction To Building Climatology - Chapter 11 - Design in The Zones OCR PDFsherin greenal100% (1)

- Borsi, Nottingham, Porter - Krier BlockDocument20 pagesBorsi, Nottingham, Porter - Krier BlockFrancisca P. Quezada MórtolaNo ratings yet

- Studio Mumbai. The Practice of MakingDocument8 pagesStudio Mumbai. The Practice of Makingfsrom3No ratings yet

- Cultural Centre at Rohtak 2Document17 pagesCultural Centre at Rohtak 2Tabish RazaNo ratings yet