Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NN THEME 120918 Malaysian Property Bubble I - The Facts

Uploaded by

nonameresearchOriginal Description:

Copyright

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

NN THEME 120918 Malaysian Property Bubble I - The Facts

Uploaded by

nonameresearchCopyright:

noname

Investment Research

Thematic Report

Malaysian Property Bubble I The Facts

Date: 18 September 2012

Executive Summary

In this paper, we address the question of whether the Malaysian property sector is in a bubble. As the property sector is very diverse, the enquiry is restricted to the residential sector in the four key economic states of KL, Selangor, Johor and Penang. Collectively, these four states contribute 75% of total residential sales and 60% of total residential transaction volume. Based on both statistics and income analysis, the Malaysian property sector is in a bubble. From a statistical perspective, measures of property activities such as property sales, transaction volume and sales to GDP ratio have all shown a marked departure from historical trends since 2007. From an income perspective, property prices are now unaffordable to the average household. Due to property prices growing at almost 3x the rate of income in recent years, Malaysia median multiple has leapt to 6.1x, well above the 3x mark that is considered affordable globally. We estimate that, in general, the average Klang Valley household can only afford a property in the RM400,000 range implying that the farther removed property prices are from this range, the more exposed they are to a correction. Specifically, considering that most listed property developers are still launching units at the RM500,000 to RM700,000 range even for the low end of their sales portfolio, we believe they are vulnerable to a correction. Too many developers are attempting to sell too many units to too few people at too high a price. The cause of the bubble can be traced to callous policies by the government and financial innovation by the property developers that took place in the last five years. In particular, the main culprits are the removal of RPGT in 2007, the all-time low interest rates in 2009 and the DIBS scheme introduced by property developers in 2009. In summary, driven by low interest rates, accommodative administrative policies and financial innovation through DIBS, the Malaysian residential property sector is currently in a bubble. Furthermore, the bubble is now at its end stage as prices are now too far removed from fundamentals. Investors should adopt a cautious stance as the sector will have limited upside potential and a sudden correction is possible.

Robin HU

robin@nonameresearch.com

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Table of Contents

Property Bubbles in General ...................................................................................... 3 The mechanics of property bubbles ....................................................................... 3 Why are property bubbles deadly? ........................................................................ 4 Scope and Method ..................................................................................................... 5 Scope restricted to residential in key economic states .......................................... 5 Two methods: Statistical analysis and income analysis ......................................... 5 The Statistical Viewpoint ............................................................................................ 7 Residential sales Marked increase since 2007 .................................................... 7 Rising sales to GDP ratio ......................................................................................... 8 Transaction volume Similar to sales, marked rise since 2007 ............................. 9 Residential price Take it with a pinch of salt ..................................................... 10 The Income Viewpoint ............................................................................................. 14 Malaysian household spending pattern ............................................................... 14 The average Klang Valley household affordability is RM400k ............................. 14 House price growing faster than household income ........................................... 16 Rising price to income ratio .................................................................................. 16 Why Residential Property is in a Bubble .................................................................. 18 Review of key points from previous sections ....................................................... 18 Why Msians cant afford what the listed developers are selling ......................... 19 Where is the bubble then? ................................................................................... 20 Factors Contributing to the Bubble .......................................................................... 21 A tale of two halves .............................................................................................. 21 Bad policy decisions nurtured the bubble ............................................................ 21 The Removal of RPGT ............................................................................................... 23 Malaysia RPGT regime .......................................................................................... 23 RPGT removal spurred property activities ........................................................... 23 The Nasty DIBS ......................................................................................................... 25 The background and nature of DIBS..................................................................... 25 DIBS as a speculative tool ..................................................................................... 25 DIBS speculation drove the bubble ...................................................................... 27 How the Bubble Happened ...................................................................................... 29 Conclusion ................................................................................................................ 30

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Property Bubbles in General

The mechanics of property bubbles

Below is a brief outline of the mechanisms behind speculative bubbles in the property sector. Phase 1 (the positive shock). An initial positive shock results in a rise in property price. Due to the leveraged nature of property purchase (typically a leverage of 10x in Malaysia), the initial price rise results in outsized profits. At this point, the initial positive shock can either be interpreted by the market as transient or permanent. If the market perceives the price rise to be transient then the shock fizzles out. However, if the market interprets the shock as the start of a sustainable trend, then the perception itself (facilitated by accommodative credit environment) becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy and leads to Phase 2 Phase 2 (the bubble). In Phase 2, a positive feedback loop develops and fuels the bubble. The positive feedback loop typically consists of a mutually reinforcing interaction between rising property prices, speculative profits and accommodative credit policy. Rising property prices result in outsized profits due to leverage. Rising property prices also result in bank expanding mortgage lending due to appreciating collateral. Outsized profits attract new speculators and easy mortgages allow more people to participate in the nascent bubble. Both developments provide fuel for further rise in property prices. Eventually property prices become too far removed from fundamentals and the whole sector becomes susceptible to a negative shock Phase 3 (the negative shock.) In Phase 3, property prices are now too far removed from fundamentals and are being sustained only by new speculative money flowing into the sector. In this phase, the property sector resembles a Ponzi scheme and similar to all Ponzi schemes, the inbuilt unsustainability of a self-perpetuating price rise serves as an infallible pin that could be relied upon to prick the bubble. Other factors could also act as a pin e.g. government action, macro instability etc. Whatever the pin may be, the bubble is pricked and property prices began to fall Phase 4 (the bursting of the bubble) Falling prices now result in outsized loss due to leverage. At a leverage of 10x in Malaysia, a 10% decline in property price is all it takes to wipe out all invested capital. Such amplified loss results in panic dumping of properties and creates an intense downward spiral. The reinforcing mechanism described in Phase 2 now works in reverse. Losses began to spread beginning with the property speculators and property developers and if the bubble was serious enough then the banks and even the government will be affected as well. In this manner, a property problem could potentially lead to a banking problem which in turn leads to a fiscal problem

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Why are property bubbles deadly?

Credit bubbles amplifies damage. At the heart of every bubble is the relentless bidding up of prices. However, the bidding process may or may not be facilitated by borrowings. Property bubble without credit. Assume the situation is such that properties can only be purchased with 100% downpayment i.e. no borrowing allowed and hence no mortgages. Therefore, a RM100,000 property can only be purchased if you have RM100,000. Furthermore, if the price subsequently increased to RM105,000 then the gain is (RM105,000 - RM100,000)/RM100,000 or 5%. Under such circumstances, a bubble could conceivably still form but speculation is more difficult here compared to if credit is freely available Property bubble facilitated by credit. Assume that the situation is now such that credit is available and properties can be purchased with a 10% downpayment. Therefore, a RM100,000 property can now be purchased with only an upfront payment of 10% or RM10,000. Furthermore, if the price subsequently increased to RM105,000 then the gain is (RM105,000RM100,000)/RM10,000 or 50%. This is 10x the gain of the aforementioned no-credit scenario. Clearly, if circumstances are at all conducive to the formation of bubble, then credit will further accelerate that formation

Bubbles also deflate differently depending on whether credit was involved. Property deflation without credit. If the preceding bubble was formed sans credit then the deflation directly impacts only property speculators. The property developers may also feel the pain due to an overall slowing market but banks and government are generally not affected as under this scenario, property purchases involve only the speculator and the developer Property deflation with credit. In contrast, if the preceding bubble was facilitated by credit then a debt deflation could ensue. A property speculator facing rapidly falling property price will quickly accumulate negative equity. For example, on a 10% downpayment basis, a speculator will put in RM10,000 for a RM100,000 house and borrow the remaining RM90,000. If the property subsequently declined 15% to RM85,000, the speculator now has negative equity of RM5,000

Debt deflation is malignant as it could lead to mortgage defaults which if sufficiently pervasive, will impact not only the property sector but the banks and the larger economy as a whole. Faced with defaults, banks will tighten lending which will then lead to further decline in property price, reinforcing the downward spiral. If the problem is serious enough, banks could suffer losses or outright collapse. Property bubbles are frequently credit bubbles. Frequently, property bubbles are deadly as they are generally credit bubbles due to the pervasiveness of mortgages in the property sector. Downpayment requirement varies from countries to countries and from time to time. In Malaysia, downpayment is only 10% for the first purchase translating into an inbuilt leverage of 10x. Subsequent purchase may attract downpayment of up to 30% resulting in a still high leverage of 3.3x. In short, because property bubbles are frequently credit bubbles, the fallout from the bursting of property bubbles generally extend beyond the property sector.

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Scope and Method

Scope restricted to residential in key economic states

The property sector can be subdivided into different segments such as residential, commercial, retail and industrial. These segments have different dynamics and as such, it is important to delineate right at the outset the segment under investigation. In this report, the analysis and any conclusions drawn are restricted to only the residential segment in four key economic states KL, Selangor, Penang and Johor. These four states alone contribute 75% of total residential sales and 60% of total residential transaction volume. This particular segment is chosen for a number of reasons. Firstly, the residential segment is relatively more susceptible to bubble conditions compared to say the retail, commercial or industrial segments. This is because the residential segment has the widest reach (everyone will eventually buy a house but not everyone will buy a shopping mall) and the least sophisticated decision-makers (participants in non-residential segments are typically professionals). The residential segment ubiquity and easy participation by large numbers of unsophisticated participants provide fertile ground for speculation and thus bubble formation. Secondly, all the major listed property developers in Malaysia derive the majority of their revenue from the residential segment in the four key economic states. At the end of the day, the analysis here is meant to serve investors. Therefore, the analysis must focus on the segments that the listed property developers are most exposed to.

Two methods: Statistical analysis and income analysis

Two methods are used to establish that the Malaysian residential property segment in the four key economic states of KL, Selangor, Johor and Penang is in a bubble. The two methods are: Statistical analysis Income analysis

In statistical analysis, statistics from NAPIC is used to show that: both property sales value and property transaction volume have behaved abnormally in the years since 2007 these changes are caused by specific events that took place circa 20072009

For statistical analysis to succeed, both points need to be established as sales value and transaction volume exhibiting a break from historical trend may not be a sufficient cause for concern by itself. It is only a concern if it can be shown that the break from historical trend was caused by specific events. This establishes causation and help explains the bubble. In income analysis, we attempt to show that the average property price has increased materially beyond the reach of the average households. The income approach relies on inconsistency between the income data and the property price data to demonstrate that both cannot be correct. Either the property price is

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

correctly captured and the average income is understated or the average income is correctly captured and the property price is too high. The two methods above can be referred to in isolation. One point to note is that statistics is a very crude tool as statistics aggregates away substantial amount of important details. For example, using the median price for houses essentially takes only the middle of the price distribution and ignores prices on both the left and right tails of the distribution. As such, even if prices changed substantially at the tails (say high-end condominium prices doubled), the median remains unaffected. All in all, the income approach is preferred due to its inbuilt consistency check. Given a property price, the range of income and mortgage rates that would make the property affordable can be easily derived. Here we do the reverse by first establishing a range income and then use that to show that the current property prices are unaffordable.

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

The Statistical Viewpoint

Residential sales Marked increase since 2007

Half of total property sales is residential. Total property sales was RM138bn in 2011. The majority of property sales, 45% or RM62bn, was contributed by residential. Commercial property was the second largest, constituting 20% or RM28bn of sales. Other segments constituted the remaining 35%.

Figure 1: Total property sales breakdown 2011

Source: NAPIC

75% of sales came from just four states. Geographically, Selangor was the single largest state for residential property sales contributing RM23bn or 37% of RM62bn residential sales. This was followed by KL (18%, RM11bn), Penang (12%, RM8bn) and Johor (8%, RM5bn). In total, 75% of all residential sales came from these four states. In fact, Selangor and KL by themselves already occupied 55% of sales.

Figure 2: Residential sales by geography 2011

Source: NAPIC

Marked increase in sales since 2007. Residential sales has shown a marked growth since 2007. Annual residential sales have doubled to RM62bn in 2011 from just RM29bn in 2006. This is an annualized growth rate of 16% CAGR over the five year period 2006-2011

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

In comparison, residential sales grew by only 6% CAGR over the preceding five year period 2001-2006

Table 1: Comparison on residential sales growth over two five year periods Five year 2001-2006 Growth in residential sales value (CAGR) 6% p.a. Five year 2006-2011 16% p.a.

Growing even during global recession? Looking closer at Figure 3, it can be seen that the years 2007, 2010 and 2011 were years with very strong +20% growth. In fact, at 13%, 2008 was a year of very strong growth as well considering that sales in the fourth quarter of 2008 were effectively decimated by the Lehman crisis of Sep 2008. Seen in this light, it appears that the Malaysian residential property sector has been on an upswing for at least half a decade punctuated only by the global recession in 2009. Even then, the 1% growth in 2009 was still good considering it took place against a backdrop of global recession1.

Figure 3: Malaysia residential sales and growth 1989-2011

Source: NAPIC

Rising sales to GDP ratio

Sales to GDP ratio now above historical trend. In the last decade, there has been only four times that the residential property sales to GDP ratio has risen above 6%. The years were 2004, 2009, 2010 and 2011. As can be seen, three out of the four years took place in the last three years. Last year residential sales to GDP ratio was the highest at 7.3%. This means that the marked rise in residential sales since 2007 was not a byproduct of, and in tandem with, an overall rise in Malaysia GDP. Instead, it seems

We will show how the Malaysian property sector has been sustained by artificial tools beginning 2007 in later parts of this report but for now note that the property sector began to take off in earnest in 2007 and continued growing despite the global recession

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

to have been driven by endogenous factors unique to the Malaysian property sector, resulting in property sales growing faster than GDP.

Figure 4: Malaysia residential sales to GDP 2000-2011

Source: NAPIC

Transaction volume Similar to sales, marked rise since 2007

Selangor accounts for a quarter of transaction volume. Total residential property transaction volume in Malaysia was 269,789 units in 2011. Again, the single largest contributor was Selangor (28%, 75k units) followed by the other three key states KL (9%, 24k units), Johor (12%, 31k units) and Penang (12%, 31k units)2. Collectively, these four states contributed 60% of total transaction volume.

Figure 5: Residential units sold by state 2011 No of residential units sold KL Selangor Johor Penang Other states Total Malaysia

Source: NAPIC

2001 9,963 41,773 24,594 14,133 85,745 176,208

2006 14,374 48,228 22,958 15,439 81,556 182,555

2011 24,314 75,344 31,084 30,674 108,373 269,789

Marked rise in transaction volume since 2007. Similar to sales, there has been a marked rise in transaction volume since 2007. From Figure 6 below, it can be seen that transaction volume spiked to 9% in 2007 in stark contrast to the 0% in 2006 and -7% in 2005. Then transaction volume rose another 9% in 2008, declined 2% in 2009 due to global recession before resuming at 7% in 2010 and a huge 19% in 2011.

Incidentally, in terms of transaction volume, KL and Selangor are mirror image of each other. About half of KL transactions were condominiums/apartments while about half of Selangor transactions were terraced houses. On the flipside, 20% of KL sales were terraced houses while 20% Selangor transactions were condominiums/apartments.

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Figure 6: Number of residential sales in Malaysia

Source: NAPIC

Spike in volume a departure from historical trend. To put into perspective how abnormal the spike in transaction volume, the table below compares two five-year periods. In the five years period 2001-2006, transaction volume was as good as flat at 0.7% CAGR In the five years period 2006-2011, transaction volume grew dramatically to 8% CAGR, a stark contrast to the preceding five year period 2001-2006

Figure 7: Growth in residential transaction volume Five year 2001-2006 Growth in residential transaction volume (CAGR) 0.7% p.a. Five year 2006-2011 8% p.a.

Residential price Take it with a pinch of salt

The problem with house price statistics. In earlier sections, we highlighted that statistics can be a very crude tool for decision making. This is best exemplified by property price statistics. For example, the two statistics used above, sales value and transaction volume, are actually fairly reliable due to the nature of how these statistics are recorded. Property transactions are very transparent and recorded in details by the government in order to establish rights to properties. That is why every transaction incurs a stamp duty. As a result, property transactions (sales value and transaction volume) are comprehensively and compulsorily captured. They are exhaustive. In contrast, property prices are not captured in this manner. Instead, a sampling method is used. Sampling entails pre-selecting a particular set of properties and updating its market price periodically. Immediately, the sampling approach presents some problems. Firstly, the pre-selected sample must be representative and this is clearly debatable

10

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Secondly, what exactly is the market price and what does it mean to have a market price? In fact, we think the notion of a market price is itself incorrect and misleading. The term last transacted price is probably more apt and as any stock investor can elucidate, last price is not the same as market price at all

Official statistics a bit removed from reality. Theory aside, the table below highlights how unrealistic the official property price statistics can be. For example The average price for a 2-3 storey terraced house in Selangor was captured at RM300,000 in 2009. Any Malaysians will agree that this is unrealistic. A terraced house in Petaling Jaya would already cost at least RM700,000. Farther out in Shah Alam, the price would probably be at closer to RM500,000 in 2009 (RM650,000 in 2011). In fact, one would be lucky to get a mid-end condominium for RM300,000 in PJ what more RM300,000 for a 2 storey terraced house Similarly, the price of a terraced house in KL was recorded as RM519,000. This is again unrealistic. One would be lucky to afford a 1-bedroom apartment in KL for RM500,000

These price points are similarly divorced from reality in Johor and Penang as well. Note also that the price increase of 2.8% for Selangor is also highly suspicious. The actual rate is probably closer to 10%-15% on a crude estimate basis.

Table 2: Price for 2-3 storey terraced house RM KL Selangor Johor Penang Negeri Sembilan Perak Melaka Pahang Terengganu* Kelantan* Perlis* Sabah Sarawak

Source: NAPIC, *1-1/2 storey terraced house

2000 288k 233k 176k 196k 162k 102k 136k N/A 66k 73k 68k 132k N/A

2009 519k 300k 202k 387k 312k 164k 209k N/A 119k 93k 108k 295k N/A

CAGR 00-09 6.7% 2.8% 1.5% 7.8% 7.5% 5.4% 4.9% N/A 6.8% 2.7% 5.2% 9.3% N/A

In line with the above, we will rely as little as possible on NAPIC price statistics and property price indices. Instead, we will rely on other sources such as actual real estate agent quotations, advertised prices and developers launch prices. Official property price growth 4.4% looks too low. Nonetheless, below is a quick view of some price statistics from NAPIC for completeness purposes as these data points are frequently quoted. According to the official statistics from NAPIC, in the decade between 2001-2011, Malaysia overall property price increased by 4.4% per annum. More recently, in the five year period between 2006-2011, the growth was

11

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

5.1% CAGR with higher than average growth seen in the last two years 2010 (8.2% per annum) and 2011 (6.6% per annum).

Figure 8: Malaysia residential price growth

Source: NAPIC

Geographically, the average increase in property price in the five year period between 2006-2011 was 6.3% for KL, 5.7% for Selangor, 2.6% for Johor and 5.8% for Penang.

Figure 9: Residential price growth in KL, Selangor, Penang and Johor

Source: NAPIC

12

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Actual property price growth closer to 10%-15%. In our view, the official statistics tend to understate actual increase in property price (perhaps due to either their sampling or averaging methods). This can be substantiated by referring to the actual launch price disclosed by the listed property developers. Take SPSB developments for example: A SPSB two storey terraced house in Setia Alam was sold for RM218,000 in 2004 while in comparison a similar house in the township was launched at RM668,000 in 2011. This represents an annualised increase of 17% per annum In Setia Eco Park, semi-detached that were first launched in 2005 at around RM600,000 now command prices above RM2 million, an annualised increase of 22% per annum.

Such price increase is not unique to SPSB but can be observed in developments launched by almost all other developers such MSGB, E&O, BRDB, GAM, IJMLD, etc. As such, it is estimated that the actual increase in property price is not 4.4% per annum as calculated by NAPIC but closer to 10%-15% per annum based on the developers launch prices and secondary sales price.

13

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

The Income Viewpoint

Malaysian household spending pattern

Breakdown of spending according to official statistics. According to official statistics3, there are 6.4m households in Malaysia. The largest concentration of households can be found in Selangor (1.3m households, 21% of total), Johor (0.8m, 12%) and Sabah (0.6m, 10%). The average Malaysian household consists of four persons and earns an income of RM4,7004 per month5 and spends RM2,465 per month. As expected, the three largest components of expenditure are housing (RM583 per month, 24% of total), food (RM447, 18%) and transport (RM361, 15%). Also note that almost 80% of housing expenditure is related to the cost of housing itself. Ancillary costs such as utilities takes up the remaining 20%.

Table 3: Monthly RM expenditure per household (urban) 2009 RM Food & Non Alcoholic Beverages Clothing & Footwear Housing, Water, Electricity, Gas Furnishing, Household Equip Health Transport Communication Recreation & Culture Education Restaurants & Hotels Miscellaneous Monthly expenditure per household

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia

2009 447 79 583 100 33 361 147 121 39 285 270 2,465

18% 3% 24% 4% 1% 15% 6% 5% 2% 12% 11% 100%

The average Klang Valley household affordability is RM400k

Average Msian household can only afford a RM110k unit. Based on the official statistics above, the average Malaysian household spend RM583 per month on housing and utilities (the actual housing component itself is only RM466). Nevertheless, let us assume that the average Malaysian household spend higher than this, say RM600, on housing alone. For RM600 per month, on a 5%6 30 year mortgage, the average Malaysian household can only afford at most a RM110,000 unit.

3 4 5 6

Department of Statistics, Malaysia 2009 Urban household 75% of Malaysian household earns less than RM5,000 per month

The current (floating) mortgage rate is closer to 3.75%-4.00% but we do not think this is sustainable. We have used 5% which is not too different from the current fixed mortgage rate 4.8%

14

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Average Klang Valley individual can only afford a RM200k unit. The official average household income of RM4,700 per month is an average taken across the whole of Malaysia and as such may be lower than the average income in key urban areas. In particular, key economic areas such as the Klang Valley should have higher household income. This is indeed the case with the official average household income for Klang Valley closer to RM7,000 per month. Let us assume that the average income in Klang Valley is higher than the official statistics of RM7,000. In fact, let us assume it is RM8,000 or alternatively, the average income for an individual in Klang Valley is half of this or RM4,000. From this gross income, we will then deduct statutory contributions and typical monthly expenses in order to derive as the residual, the maximum income available for housing. The calculation is shown in Table 4 below. As can be seen, based on an average individual gross income of RM4,000, after deductions for statutory contributions and monthly expenses, only RM1,110 is available for mortgage payment (note we have not imputed savings). For RM1,100 per month, the average individual in Klang Valley can only afford a property around RM200,000. This is 33% lower than the average terraced house price of RM300,000 in Selangor and 60% lower than the average terraced house price of RM516,000 in KL. In other words, if you are an average individual residing in Klang Valley, then even with no savings, you cannot afford a terraced house.

Table 4: Estimated maximum amount available for housing (individual) RM Gross income Tax EPF Net income Food Transport, parking, car installment Others Max amount available for housing 2009 4,000 (300) (440) 3,260 (500) (1,200) (450) 1,110

Average Klang Valley household can only afford a RM400k unit. Now if we approximate a household maximum available fund for housing by simply multiplying the above RM1,100 limit for an individual by two, then the average household in Klang Valley can only afford a property around RM400,000 which is actually close to average terraced house price of RM300,000 in Selangor and RM516,000 in KL. In summary, based on statistics, it can be concluded that The average household cannot afford an average terraced house in Selangor or KL The average Klang Valley individual also cannot afford an average terraced house in Selangor or KL Only with the combined income of two Klang Valley individuals, devoting all their income to mortgage repayment (no savings, after deductions for statutory contributions and monthly expenses), can a terraced house in Selangor or KL be considered affordable

15

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

House price growing faster than household income

Officially property price growth in line with income growth. Anecdotally, typical starting pay for a fresh audit graduate ten years ago was RM2,000 compared to the current RM3,000. This translates into a growth of 4% per annum in line with the growth in average household income of 3.7% as tabulated by the department of statistics. In comparison, the property house price in Malaysia increased by 4.4% over roughly the same period (see Table 5 below) with 6% in KL, 3.9% in Selangor, 2% in Johor and 5% in Penang. This seems to show that the average property price increase was only slightly above the average household income increase.

Table 5: House and income growth rate Source KL Selangor Johor Penang Malaysia Average household income(urban)*

*2002-2009

NAPIC NAPIC NAPIC NAPIC NAPIC Dept of statistics

House Price Index 2001-2011 6.0% 3.9% 2.0% 5.0% 4.4% 3.7%

Terraced house 2000-2009 6.7% 2.8% 1.5% 7.8% N/A

But in reality, property price growth 3x that of income. As we highlighted previously, price statistics from NAPIC should be taken with a pinch of salt as the 4.4% estimated rate of growth in house price appears too low. Instead, based on the developers launch price, the average increase in property price should be closer to 10%-15% p.a. in the last five years. On this basis, the average property price increase (10%-15%) is actually almost 3x that of the average salary increase (3.7%). In other words, property price has increased disproportionately faster than income increase in the last five years.

Rising price to income ratio

Globally, median multiple of 3x is considered affordable. Based on median multiple (median house price divided by gross before tax annual median household income), the Demographia International Housing Affordability classify housing markets into four categories as per the table below. Historically, the median multiple clustered around 3x globally and as such, markets with multiples 3x and below are considered affordable. Affordability declines as the multiple increases.

16

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Table 6: DIHA affordability classification Median multiple 3x and under 3.1x to 4.0x 4.1x to 5.0x 5.1x and over

Affordable Moderately unaffordable Seriously unaffordable Severely unaffordable

Source: DIHA

Applying the above definition, DIHA derived the following median multiples for the selected countries below. Some of the countries considered unaffordable based on this definition includes Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, New Zealand and United Kingdom. In contrast, the two countries that has just experienced a property bubble, Ireland and United States, now have median multiple closer to the historical 3x.

Table 7: Median multiple for selected countries 2012 National median 6.7 4.5 12.6 3.4 6.4 5.0 3.1

Australia Canada Hong Kong Ireland New Zealand United Kingdom United States

Source: DIHA

With a multiple 6.1x, Malaysia is unaffordable. Based on official statistics7, the mean household annual household income in Klang Valley is RM84,000 (RM7,000 x 12) the mean price of a terraced house is RM516,000 in KL and RM300,000 in Selangor

This implies a median multiple of 3.6x in Selangor and 6.1x in KL. Considering current launches are still being priced at minimum in the RM500,000 to RM700,000 range in Selangor and KL, the actual median multiple is closer to 5.9x to 8.3x, significantly above the 3x that DHIA considers affordable.

Table 8: Malaysia median multiple 2011 RM 84,000 516,000 300,000 Median multiple 6.1x 3.6x

Annual household income Klang Valley Mean price terraced house KL Mean price terraced house Selangor

Here we used mean instead of median as per DIHA due to data limitation

17

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Why Residential Property is in a Bubble

Review of key points from previous sections

All indicators point towards a bubble. Based on statistics, we arrived at the following: 1. There has been a marked increase in sales value since 2007. Average five year CAGR increased from 6% to 16% (pg 7) 2. There are only four years in the last decade where the sales to GDP ratio has risen above 6%. The years were 2004, 2009, 2010 and 2011 (pg 8) 3. There is a marked increase in transaction volume since 2007. Average five year CAGR increased from 0.7% to 8% (pg 9)

Table 9: Comparison of residential sales value and transaction volume CAGR Growth in residential sales value Growth in residential transaction volume Five year 2001-2006 6% p.a. 0.7% p.a. Five year 2006-2011 16% p.a. 8% p.a.

And based on income, we arrived at the following: 4. The average Klang Valley household can afford only properties in the RM400,000 price range (pg 15) 5. House prices have grown faster than income. Our estimated actual rate of growth of house price of 10%-15% is almost 3x the 3.7% growth in income (pg 16) 6. Malaysia median multiple of 6.1x is significantly above the 3x that DHIA considers affordable (pg 17) Therefore based on both statistics and income, all six separate indicators point to the same conclusion that the Malaysian property sector is now in a bubble8. And by bubble, we mean that the sentiments in the property market is now overly positive and removed from fundamental resulting in the average property prices being pushed beyond the affordability of the average household. All these six indicators are independent of each other yet they are consistent in their conclusion. Not only that, the statistics also singled out 2007 as the year where the bubble took off in earnest. The next section will provide an explanation for this.

As a reminder, our scope is restricted only to residential property segment in KL, Selangor, Johor and Penang

18

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Why Msians cant afford what the listed developers are selling

Only 12% can afford what the listed developers are selling. Out of a total transaction volume of 270k units for Malaysia, the four states, KL, Selangor, Johor and Penang contributed 60% or 161k units. And out of this 161k units sold, only a slim 12% or 20k units were priced at RM500,000 and above. 5,600 units from KL 10,300 units from Selangor 900 units from Johor 3,200 units from Penang

Expectedly, 23% of residential units in KL were transacted at RM500,000 and above. However, once we moved out of KL, the ratio drops quickly to 14% in Selangor, 3% in Johor and 11% in Penang. This has important implication for the listed property developers. As the listed developers sales portfolio typically consists of property priced at RM500,000 and above, this implies that the listed property developers are effectively serving only the top 12% of the market and with 50% of that market concentrated in Selangor. It is a narrow market and they are hardly catering to the mass market at all.

Table 10: Residential units sold by price range 2011 KL 12,874 5,807 3,402 2,231 24,314 23% Selangor 47,485 17,551 7,286 3,022 75,344 14% Johor 26,440 3,722 775 147 31,084 3% Penang 21,347 6,095 2,401 831 30,674 11%

<RM250k RM250k to RM500k RM500k to RM1m >RM1m Total % more than RM500k

Source: NAPIC

Current selling price implies too high a median multiple. On pg 15, it was highlighted that the average household in Klang Valley can only afford a property around RM400,000 which is close to average terraced house price of RM300,000 in Selangor and RM516,000 in KL. However, most of the listed property developers are already launching units at a minimum RM500,000 to RM700,000 range, higher than the official average terraced price of RM300,000 in Selangor and RM516,000 in KL. At this RM500,000 to RM700,000 price range, the median multiple jumps to 6.0x to 8.3x, materially above the 3x that DHIA considers affordable. If we consider the average selling price of properties launched by listed developers (which is closer to RM700,000) instead of the average terraced house price of RM300,000 in Selangor and RM516,000 in KL (both already understated in our view), then the problem of affordability becomes clear. Most people simply cannot afford what the developers are selling. In fact, 88% of Malaysians cannot afford to buy what the listed developers are selling.

19

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Where is the bubble then?

Price instead of location definition. Property, by nature, is not homogeneous. Two units in the same vicinity may be priced differently for multitude of reasons such as design, build quality, furnishing, amenities, developers reputation, etc. As such, it would not be helpful to say, for example, that condominiums in location X is in a bubble. Instead, we think it is more helpful to highlight the bubble from a perspective of price and say for example that condominiums priced above RMXXX,XXX is in a bubble. Even then, this can also be inadequate for a RM500,000 condominium may be expensive in the suburb but surely it is cheap if it is located a stones throw away from KLCC. All in all, it makes more sense to highlight the bubble from a price perspective rather than categorically by location. After all, our definition of bubble is made with reference to affordability. That being said, considering that the average Malaysian household can only afford properties circa RM400,000 based on income, then naturally the farther property prices are removed from this mark, the more unsustainable they are. Be cautious at RM500,000 and above. In our view, based on the number of units being offered for sale, supply outstrips demand in the following segments Condominiums between RM400,000 to RM600,000 are rather bubbly. RM600,000 and above is overly bubbly Terraced houses between RM600,000 to RM800,000 are rather bubbly. Anything close to RM1m is overly bubbly Price guides are less helpful for semi-detached and bungalows

Table 10 is a handy guide. As can be seen, once outside KL, property priced at RM500,000 and above are effectively catering to top 12% of buyers. More specifically, top 14% in Selangor, top 3% in Johor and top 11% in Penang. Cumulatively, this amounts to 5,600 units in KL and 14,500 units in the remaining states of Selangor, Johor and Penang (and this was during 2011, a boom year for property). There is simply not enough households that can afford that many units priced at such range.

20

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Factors Contributing to the Bubble

A tale of two halves

Why two distinct halves? From Table 9 in the previous section, it is obvious that residential sales value and transaction volume exhibited two very distinct periods. The second five year period 2006-2011 clearly has much higher growth compared to the first five year period 2001-2006. Sales annual growth jumped to 16% p.a. in the second period compared to 6% in the first period Transaction volume annual growth jumped to 8% p.a. in the second period compared to a negligible 0.7% p.a

Why do the two periods differ so much in growth rate? And why was there a spurt in activity from 2007 onwards? The answer lies with bad policy decisions.

Bad policy decisions nurtured the bubble

Property sector stoked by bad policy decisions since 2007. The property sector is very susceptible to policy decisions as the government controls the single key determinant of housing affordability; the interest rate. A 100bps change interest rate will change housing affordability by around 10%-15%. Moreover, the government also decides on other administrative policies that directly affect the property sector such as the loan-to-value ratio (LTV), interest deductibility for housing, withdrawal of pension fund for housing purposes and the most important component of all, the real property gains tax (RPGT). Unfortunately for Malaysians (but fortunately for the property developers), the government loosened its stance on all fronts. The RPGT was abolished on 1 April 2007. Capital gains tax declined from 30% to zero overnight The central bank of Malaysia BNM cut the overnight policy rate (OPR) three times for a total 150 bps between Nov 2008 and Feb 2009, bringing the OPR from 3.5% to an all-time low of 2% where it stayed for a year. Consequently, the BLR (which the mortgage rate is based on) was brought to its all-time low of 5.55% as well (see Figure 10 below). Malaysia had never seen such low rates before. (The effective mortgage rate was even lower. Whereas previously banks used to price mortgage rate at BLR plus, in the last few years banks have been pricing mortgage at BLR minus. For example, despite the current BLR of 6.6%, banks are still currently offering 30 year mortgages at BLR minus 2.4% resulting in a still very low effective interest rate of 4.2%. In fact, it is not uncommon to find mortgage rates at sub 4% at all)

21

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Figure 10: Malaysia OPR and BLR 2006 to 2012

Source: CEIC

The government provided tax relief on interest paid on housing loan up to RM10,000 a year for three years for properties purchased between Mar 2009 and Dec 2010 From 1 January 2008, the government allowed monthly EPF withdrawal for housing purposes9 Liberalisation of Foreign Investment Committee ruling on foreign purchases, removing the cap on the number of houses foreigners can buy and to allowing them to borrow from local banks

Ripe for a bubble. An all-time low interest rates, removal of capital gains tax, interest deductibility and other administrative policies really ensure that property prices have nowhere else to go but up. In fact, it is almost as if the government wanted a property bubble as they seemed to have used every tricks in the bag to make sure the bubble inflates. Nevertheless, in our view, the single most important driver of the bubble was actually introduced not by the government but by the private sector. This is the DIBS scheme introduced by private developers in January 2009 (specifically it was first introduced by SPSB). Above and beyond the aforementioned callous policy decisions by the government, it was really DIBS that provided the afterburner to propel the market to new speculative height. The fact that low interest rates stoke property prices has already been abundantly discussed by others so we will not dwell further on this. Instead, we will look at RPGT and DIBS in the next section as they relate specifically to Malaysia.

The impact of this is best explained in SPSB own words and we quote verbatim The governments landmark decision to allow monthly EPF withdrawals to fund mortgages, which is estimated to unleash some RM9.6bn annually, will profoundly impact the property market. We expect this to spur demand for a wide spectrum of properties across the board as the 5 million EPF contributors take advantage of this flexibility to boost their purchasing power

22

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

The Removal of RPGT

Malaysia RPGT regime

The removal of RPGT. Tax on property in Malaysia was introduced in 1974 under the Land Speculation Tax Act which, as its name implies, was put into effect to curb property speculation. The year after, in November 1975, the Land Speculation Tax Act was replaced with the present Real Property Gains Tax. Malaysian RPGT regime can be divided into six periods: Period A ran the longest from 1975 to May 2003. During this period, RPGT was as high as 30% for disposal within two years before graduating to 20% in 3rd year and eventually zero after fifth year RPGT was suspended twice. Once from Jun 2003 to May 2004 (Period B) and another time from April 2007 to Dec 2009 (Period D). During these periods, no tax was payable There was an intermission where RPGT was reintroduced from Jun 2004 and Mar 2007 (Period C) at the old rates that existed pre May 2003 After the second suspension of RPGT in Period D, RPGT was reintroduced on Jan 2010 but at a much lower rate of 5% (Period E) We are currently in Period F which is similar to Period E except that the tax rate has been increased slightly to 10% for property disposed within two years

The current RPGT regime of 10% is very mild both with reference to historical rates of 30% and also in comparison to other countries.

Table 11: Malaysia RPGT regime Period A Nov75 31 May 03 30% 20% 15% 5% Nil Period B 1 Jun 03 31 May 04 No RPGT Period C 1 Jun 04 31 Mar 07 30% 20% 15% 5% Nil Period D 1 Apr 07 31 Dec 09 No RPGT Period E 1 Jan 10 31 Dec 11 5% 5% 5% 5% Nil Period F 1 Jan 12 current 10% 5% 5% 5% Nil

Disposal within 2 years Disposal in 3rd year Disposal in 4th year Disposal in 5th year Disposal after 5th year

RPGT removal spurred property activities

Removal of RPGT stimulated property activities The removal of RPGT has a stimulative effect on the property market. Figure 11 below highlights in light gray the years where RPGT was removed and the corresponding upward swing in price and transaction. Once the RPGT was removed in 2003-2004, sales grew 9% and 27% in 2003 and 2004, a marked departure from the 1% and -5% recorded in the preceding years 2001 and 2002

23

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

This can be observed again the second time RPGT was removed in 20072008 where sales leapt 24% and 13% in 2007 and 2008. Again this is in contrast to the -3% and 4% recorded in the preceding years 2005 and 2006 The year 2009 was an exception as despite RPGT being removed, sales growth was only 1% due to the global recession The most recent years 2010 and 2011 were also years of high growth as RPGT was reintroduced not at the historical 30% but at the almost negligible rate of 5%

Figure 11: Malaysia residential sales growth 2001-2011

Source: NAPIC

Similarly, from a property transaction perspective, the same behavior can be observed. The years where RPGT was removed were years where transaction volume leapt strongly and departed markedly from years where RPGT were in force (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: Malaysia residential transaction growth 2001-2011

Source: NAPIC

Therefore, historically at least, the removal of RPGT has consistently stimulated property price and transaction volume.

24

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

The Nasty DIBS

The background and nature of DIBS

What is DIBS? Subsequent to the global recession following the Lehman crisis in September 2008, the Malaysian property went into remission. As SPSB described it10 The global financial crisis brought consumer sentiment to an all-time low, even below the Asian Financial Crisis levels. In the months of November and December, sales dropped more than 70% to RM30m a month compared to the preceding year. We had to think of new ways to re-ignite consumer interest. In order to spur sales, SPSB introduced the Setia 5/95 scheme. Hence, the introduction of the Setia 5/95 Home Loan Package. The financing package worked on the premise of a 5% down payment with no interest payable during construction with the purchaser servicing his 95% loan only upon completion of the property. Added incentives included in the package were the absorption of legal fees and stamp duty on the Sale & Purchase Agreement, Loan Agreement and the Memorandum of Transfer by the developer. SPSB Setia 5/95 scheme and similar schemes by other developers have since came to be known as a Developer Interest Bearing Scheme (DIBS). Under DIBS, a property buyer just needs to pay a 5% down payment. No further payment is required until the property is completed. DIBS success, copycat schemes and subsequent expansion. The DIBS was very well received and soon other developers replicated the scheme. For example, IJMLD introduced their version of DIBS named My Space Plan interest bearing scheme on 1 April 2009. In SPSB words, The financing package was launched in January 2009 and not only garnered great buying interest from the public but saw other industry players follow suit introducing various incentives for property purchasers. Overwhelming response to the campaign saw the Group extending the initial three-month period for another three months to end in July.

DIBS as a speculative tool

Why DIBS is nothing but a speculative tool. Property purchase can be naturally attractive to speculators due to its inbuilt leverage. 1. At the typical down payment of 10%, the inbuilt leverage in a property purchase is 10x 2. As long as the property price appreciation is higher than the cost of financing, then property speculation becomes highly profitable Generally, in the past, property speculation has not been attractive in Malaysia as mortgage cost and the long run rise in property prices tend to be almost similar and thus cancel each other out, resulting in no speculative gain. However, the DIBS

10

Verbatim, SPSB annual report

25

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

remedied this problem by introducing two attributes that makes it attractive to speculate on properties. Firstly, the DIBS temporarily removed the mortgage cost component by absorbing interest cost during construction. Without the mortgage cost to act as restraint, any growth in property price results in speculative profit immediately Secondly, reducing the down payment from 10% to 5% doubled the already high leverage from 10x to 20x and significantly magnifies any speculative profit

How DIBS create speculative profit. The aforementioned (1) interest cost absorption and (2) reduction of down payment from 10% to 5% work in tandem to create large speculative profits as long the property price does not decline11. Even if the property price just rose 3% in a year, the speculative profit can be very large. For example12, Assume that a speculator purchased a property for RM500,000 and sold it a year later after it has appreciated by 3% to RM515,000 The down payment is 5% or RM25,000 The gross proceed is RM515,000 less RM500,000 or RM15,000. The return is RM15,000/RM25,000 = 60%. (Alternatively, this can be derived by multiplying the asset appreciation 3% by the leverage 20x)

The reason why property speculation is now profitable is because the cost of servicing the debt during the construction period, which served as the single largest hurdle rate in the short term, has been nullified by the interest absorption clause under DIBS. Note also that the RPGT was only reintroduced in January 2010. This means that when the DIBS was first introduced in January 2009. All the speculative gain was tax free13. From bad to worse. DIBS, instead of being a temporary marketing tool, has now become a permanent fixture in property sales. Three years after it was initially conceived in January 2009 by SPSB, it is still very much alive and very much more virulent. The current variant of DIBS has become even more of a speculative tool compared to its original variant. Take for example the DIBS offered by MSGB for its M-City properties recently in 2012. In addition to the standard interest and incidental costs absorption as per the original DIBS scheme, MSGB has gone one up and introduced the following incentives 1. Reduced down payment from 5% to 2% and thereby increasing the leverage factor from an already high 20x to 50x! 2. an 8% rebate 3. partially furnished 4. 1 year maintenance

11

The property sector now resembles a Ponzi scheme. There will continue to be speculative profits so long as the property price does not decline

12 13

We have excluded a few incidental costs involved in the selling of the property Imputing RPGT will reduce the gain slightly as there are deductible allowances under RPGT

26

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Figure 13: Incentives offered by MSGB for M-City

Source: MSGB advertisement 2012

DIBS speculation drove the bubble

Why are incentives needed if property is affordable? The above MSGB property advertisement begs the question, if property is affordable, why is there then the need to offer incentives? The fact that a barrage of incentives is needed to sell a property, does this not imply that the current property price is too high? Furthermore, note how all the incentives really served to artificially support property prices. Incentives such as an 8% rebate, partial furnishing, legal fees and incidental cost absorption, interest cost absorption and 1 year maintenance (other gimmicks include guaranteed rental) all serve to prevent property prices from declining as they would in a property market left to function on its own under the rule of demand and supply. The truth is that, at current launch prices, properties are simply not affordable to many (we have justified this view on the basis of statistical and income analysis in earlier sections). All the aforementioned incentives, are really just insidious means to postpone14 a property price decline by reducing the net effective purchase price of property while keeping the gross price high. Why property developers are afraid of falling property prices. This brings up another question, why are property developers so afraid of falling property prices? Isnt selling a RM550,000 unit with RM50,000 incentives thrown in the same as selling a RM500,000 units? From a bottom line perspective, the property developers should be unperturbed. Why then do property developers not just simply sell properties at the price sans incentive but expend efforts instead in devising various incentives? This is a very peculiar situation. It is hard to think of another industry where the sellers choose to advertise a higher rather than a lower

14

We have used the word postpone rather than prevent because it is not possible to stop the property price from reverting to its fundamental price. Postpone, yes. Prevent, no.

27

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

price for their products if the sellers net profit is the same under either scenarios. Lower prices, and not higher prices, move goods. In fact, there is only another industry in which the sellers may have an interest to keep the prices high even at the expense of their net profit in the short term. It is an industry which we are familiar with i.e. the stock market. Here, speculators accumulate position in a stock and then subsequently try to create enthusiasm for a stock through upward price movement in order to (hopefully) exit the whole position at a higher price. Therefore, it is now clear why property developers artificially keep property prices high even at the expense of profitability. This is because the property prices are now so high that the sector is now being supported by speculators rather than real buyers. The real buyers have already been priced out of the market and the property developers know it. That is why they actively chose to keep property prices high (in order to appeal to the speculative buyers) instead of doing what is logical and cut prices to sell more units (in order to appeal to the buy-to-stay buyers). The property developers are fully aware that they are now catering to the speculators. Property developers or derivative sellers? It is worth mentioning that there are a number of differences between speculation in the stock market and speculation in the property market. Firstly, market activities are monitored in the stock market but not in the property market. NAPIC collect statistics but NAPIC does not have monitoring and enforcement powers similar to that of the Securities Commission. Secondly, you cannot buy stocks in the stock market with only a 5% down payment but you can do so with properties. In the financial market, there is a term for instruments that provides you exposure to an underlying asset class at a fraction of the price of the asset. It is called a derivative and this is precisely the role of DIBS in the property market. In fact, it resembles a forward contract with a very low margin requirement (2%-5%). If DIBS is a derivative, then that makes the property developers the derivative sellers. As mentioned in the opening chapter, every bubble is expedited by credit. Here, the role of credit providers is being filled by the property developers (abetted by banks).

28

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

How the Bubble Happened

In summary, here is our simplified version of how the bubble developed The removal of RPGT on 1 April 2007 kickstarted the property market but the bubble was still nascent at this stage. Nevertheless, the signs were there as residential sales growth shot up 24% in 2007 compared to only 4% in 2006. This was the second time RPGT was removed. The previous time RPGT was removed back in 2004 also resulted in a jump in activities as residential sales growth also shot to 27% then The sales momentum continued into 2008 but was decimated by the Lehman collapse in Sep 2008. Still the overall sales growth for 2008 was still good at 13% due to strong sales in earlier quarters First quarter 2009 marked the period where two developments worked in tandem to give the property market its ultimate boost. Firstly, BNM reduced the interest rate by 150bps to an all-time low of 2% and maintained it there for the whole of 2009 in response to the global recession. Correspondingly, mortgage rates dropped to an all-time low as well. Secondly, the property developers introduced DIBS which turned out to be a highly efficient speculative tool The two developments above solidified the bubble in 2009. For 2010 and 2011, the bubble essentially fed on itself and kept growing

This brings us to 2012 where sustained increase in property prices since 2007 has now resulted in properties being out of reach for the majority of households.

Figure 14: Malaysia residential sales growth 2001-2011

Source: NAPIC, years where RPGT was suspended are highlighted in gray

29

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012

Conclusion

In this paper, we address the question of whether the Malaysian property sector is in a bubble. As the property sector is very diverse, the enquiry is restricted to the residential sector in the four key economic states of KL, Selangor, Johor and Penang. Collectively, these four states contribute 75% of total residential sales and 60% of total residential transaction volume. Based on both statistics and income analysis, the Malaysian property sector is in a bubble. From a statistical perspective, measures of property activities such as property sales, transaction volume and sales to GDP ratio have all shown a marked departure from historical trends since 2007. From an income perspective, property prices are now unaffordable to the average household. Due to property prices growing at almost 3x the rate of income in recent years, Malaysia median multiple has leapt to 6.1x, well above the 3x mark that is considered affordable globally. We estimate that, in general, the average Klang Valley household can only afford a property in the RM400,000 range implying that the farther removed property prices are from this range, the more exposed they are to a correction. Specifically, considering that most listed property developers are still launching units at the RM500,000 to RM700,000 range even for the low end of their sales portfolio, we believe they are vulnerable to a correction. Too many developers are attempting to sell too many units to too few people at too high a price. The cause of the bubble can be traced to callous policies by the government and financial innovation by the property developers that took place in the last five years. In particular, the main culprits are the removal of RPGT in 2007, the all-time low interest rates in 2009 and the DIBS scheme introduced by property developers in 2009. In summary, driven by low interest rates, accommodative administrative policies and financial innovation through DIBS, the Malaysian residential property sector is currently in a bubble. Furthermore, the bubble is now at its end stage as prices are now too far removed from fundamentals. Investors should adopt a cautious stance as the sector will have limited upside potential and a sudden correction is possible.

30

nonameresearch.com | 18 September 2012 Rating structure The rating structure consists of two main elements; fair value and conviction rating. The fair value reflects the security intrinsic value and is derived based on fundamental analysis. The conviction rating reflects uncertainty associated with the security fair value and is derived based on broad factors such as underlying business risks, contingent events and other variables. Both the fair value and conviction rating are then used to form a view of the security potential total return. A Buy call implies a potential total return of 10% or more, a Sell call implies a potential total loss of 10% or more while all other circumstances result in a Neutral call.

Disclaimer This report is for information purposes only and is prepared from data and sources believed to be correct and reliable at the time of issue. The data and sources have not been independently verified and as such, no representation, express or implied, is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information or opinions in this report. The information and opinions in this report are not and should not be construed as an offer, recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any securities referred to herein. Investors are advised to make their own independent evaluation of the information contained in this research report, consider their own individual investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs and consult their own professional and financial advisers as to the legal, business, financial, tax and other aspects before participating in any transaction.

31

You might also like

- Kareen Leon, Cpa Page No: - 1 - General JournalDocument4 pagesKareen Leon, Cpa Page No: - 1 - General JournalTayaban Van Gih100% (2)

- Current Position of The Real Estate Market Written Report by KhalidDocument19 pagesCurrent Position of The Real Estate Market Written Report by KhalidKhalid GowharNo ratings yet

- 41 and 42 Tolentino Vs Secretary of FinanceDocument2 pages41 and 42 Tolentino Vs Secretary of FinanceYvon Baguio100% (1)

- UK Property Letting: Making Money in the UK Private Rented SectorFrom EverandUK Property Letting: Making Money in the UK Private Rented SectorNo ratings yet

- The Logical Trader Applying A Method To The Madness PDFDocument137 pagesThe Logical Trader Applying A Method To The Madness PDFJose GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Case-Digest-28 Inchausti Vs YuloDocument8 pagesCase-Digest-28 Inchausti Vs YuloAiemiel ZyrraneNo ratings yet

- Rental Volatility in UK Commercial Market - Assignment (REE) - 2010-FinalDocument11 pagesRental Volatility in UK Commercial Market - Assignment (REE) - 2010-Finaldhruvjjani100% (1)

- How Real Estate Bubbles Form and Burst: Lessons from MalaysiaDocument7 pagesHow Real Estate Bubbles Form and Burst: Lessons from MalaysiaerynhsNo ratings yet

- Risk Assignment NewDocument6 pagesRisk Assignment NewLiyana Syafini JumaahNo ratings yet

- OSK Research On PropertyDocument41 pagesOSK Research On PropertyjimmyttlNo ratings yet

- Levitin - Clearing The Mortgage Market Through Principle Reductions RTC 2.0Document24 pagesLevitin - Clearing The Mortgage Market Through Principle Reductions RTC 2.0annawitkowski88No ratings yet

- Growth inDocument2 pagesGrowth inJeff TewNo ratings yet

- Singapore Property Weekly Issue 292Document16 pagesSingapore Property Weekly Issue 292Propwise.sgNo ratings yet

- Its 2010 So What Should Investors and Americans Do NowDocument13 pagesIts 2010 So What Should Investors and Americans Do NowZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- Enc2135 Project 1 Final Draft-2Document8 pagesEnc2135 Project 1 Final Draft-2api-643122560No ratings yet

- Current IssueDocument10 pagesCurrent IssueFarhanie NordinNo ratings yet

- Mae ReportDocument7 pagesMae ReportAreesha KamranNo ratings yet

- Modern Sardine Management and Real Estate Investment AnalysisDocument5 pagesModern Sardine Management and Real Estate Investment Analysisswemo123No ratings yet

- Mohd Faris Bin Ruslee, Student in Finance Degree, Faculty of Business Management, MARADocument8 pagesMohd Faris Bin Ruslee, Student in Finance Degree, Faculty of Business Management, MARAMuhamad FakriNo ratings yet

- Sub Prime CrisisDocument2 pagesSub Prime CrisisGomathiRachakondaNo ratings yet

- Housing Market Imperfections Limit AffordabilityDocument5 pagesHousing Market Imperfections Limit AffordabilitySimran LakhwaniNo ratings yet

- The Case For An Open Housing Market: ArticleDocument3 pagesThe Case For An Open Housing Market: ArticleEltonNo ratings yet

- Current Issues in Financial MarketsDocument5 pagesCurrent Issues in Financial Marketsreb_nicoleNo ratings yet

- Realty Sector and Covid 19Document3 pagesRealty Sector and Covid 19Sumra KhanNo ratings yet

- 2b Cyclical and SeasonalDocument4 pages2b Cyclical and SeasonalRoseanneNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Credit Boom: Why Investing in Smaller Companies Is Not Only Responsible Capitalism But Better For Investors TooDocument13 pagesBeyond The Credit Boom: Why Investing in Smaller Companies Is Not Only Responsible Capitalism But Better For Investors TooIPPRNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesReal Estate Research Paper Topicsgw0q12dx100% (1)

- Mcgill Personal Finance Essentials Transcript Module 7: The Realities of Real Estate, Part 1Document5 pagesMcgill Personal Finance Essentials Transcript Module 7: The Realities of Real Estate, Part 1shourav2113No ratings yet

- 2008 Financial Crisis Impact on BosniaDocument16 pages2008 Financial Crisis Impact on BosniaRoman LičinaNo ratings yet

- The Anatomy of A Crisis: Speculative BubbleDocument3 pagesThe Anatomy of A Crisis: Speculative BubbleVbiidbdiaan ExistimeNo ratings yet

- 2 Quarter Commentary: Arket OmmentaryDocument13 pages2 Quarter Commentary: Arket OmmentaryracemizeNo ratings yet

- Business Communication - HDFC InterviewsDocument4 pagesBusiness Communication - HDFC InterviewsAndyNo ratings yet

- Johnny FinalDocument4 pagesJohnny FinalNikita SharmaNo ratings yet

- From the bubble economy to debt deflation and privatization-PDocument2 pagesFrom the bubble economy to debt deflation and privatization-PPrevalisNo ratings yet

- Singapore Property Weekly Issue 70Document16 pagesSingapore Property Weekly Issue 70Propwise.sgNo ratings yet

- Thesis Real Estate BubbleDocument7 pagesThesis Real Estate BubbleAndrew Parish100% (2)

- Global Real Estate Markets 2023Document8 pagesGlobal Real Estate Markets 2023ramachandra rao sambangiNo ratings yet

- Hamilton PropertiesDocument25 pagesHamilton PropertiesHendrik Ponti SimatupangNo ratings yet

- Debt Overhang and Recapitalization in Closed and Open EconomiesDocument30 pagesDebt Overhang and Recapitalization in Closed and Open EconomiesPeNo ratings yet

- A Financial Crisis Slows Productivity GrowthDocument23 pagesA Financial Crisis Slows Productivity GrowthAdriana Ferreira VillaNo ratings yet

- Innovations For Crisis' and Financial Meltdown: Implications For Growth and Economic PolicyDocument16 pagesInnovations For Crisis' and Financial Meltdown: Implications For Growth and Economic PolicySanthosh T VargheseNo ratings yet

- Outlook For 2013: A Changing Playbook: InsightsDocument28 pagesOutlook For 2013: A Changing Playbook: InsightssukeerrNo ratings yet

- Singapore Property Weekly Issue 231Document12 pagesSingapore Property Weekly Issue 231Propwise.sgNo ratings yet

- Investors' Behaviour in Real Estate: Realized by Jad EL BOUSTANI (B00153448)Document7 pagesInvestors' Behaviour in Real Estate: Realized by Jad EL BOUSTANI (B00153448)Jad G. BoustaniNo ratings yet

- The Credit Crunch: Lama MunajjedDocument11 pagesThe Credit Crunch: Lama MunajjedLama MunajjedNo ratings yet

- The Role of Accounting Standards That Causing or Exacerbating The GlobalDocument10 pagesThe Role of Accounting Standards That Causing or Exacerbating The GlobalHưng LâmNo ratings yet

- Modeling Mortgage Defaults and LossesDocument25 pagesModeling Mortgage Defaults and LossesSemaus LuiNo ratings yet

- Asim Final DissertationDocument83 pagesAsim Final Dissertationshad.jawdNo ratings yet

- Gondolin Capital LP Investor Letter 2Q22 (Prospective)Document10 pagesGondolin Capital LP Investor Letter 2Q22 (Prospective)Josh WeissNo ratings yet

- Jason Carrier Winter NewsletterDocument4 pagesJason Carrier Winter NewsletterjcarrierNo ratings yet

- DTTL CB Gpr14storesDocument36 pagesDTTL CB Gpr14storeskrazycapricornNo ratings yet

- CCGL Asm1 WANG XINRUI 3036128298 2023Document4 pagesCCGL Asm1 WANG XINRUI 3036128298 2023XINRUI WANGNo ratings yet

- Brook Helmling Enc 2135 Final Draft 1Document9 pagesBrook Helmling Enc 2135 Final Draft 1api-607273339No ratings yet

- China Property Crisis - Why The Housing Market Is Collapsing and The Risks To The Wider EconomyDocument8 pagesChina Property Crisis - Why The Housing Market Is Collapsing and The Risks To The Wider Economyi wayan suputraNo ratings yet

- Sub Prime CrisisDocument17 pagesSub Prime CrisisrakheesinhaNo ratings yet

- Monetary Fiscal Policy Part IIIDocument3 pagesMonetary Fiscal Policy Part IIIsaanchigoel007No ratings yet

- BBAC304 AssessmentDocument17 pagesBBAC304 Assessmentsherryy619No ratings yet

- Money Market Instability: Interconnected CrisisDocument20 pagesMoney Market Instability: Interconnected Crisisctb001No ratings yet

- China Credit Spotlight: The Lending Landscape Is Shifting For Property DevelopersDocument7 pagesChina Credit Spotlight: The Lending Landscape Is Shifting For Property Developersapi-227433089No ratings yet

- DKAM ROE Reporter April 2020Document8 pagesDKAM ROE Reporter April 2020Ganesh GuhadosNo ratings yet

- Supplementary Notes: Capital StructureDocument24 pagesSupplementary Notes: Capital StructureJohn ReedNo ratings yet

- Singapore Property Weekly Issue 240Document15 pagesSingapore Property Weekly Issue 240Propwise.sgNo ratings yet

- NN THEME 121027 The Investment Case For ChinaDocument56 pagesNN THEME 121027 The Investment Case For ChinanonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN AAPL 130228 The Case Against IPrefsDocument8 pagesNN AAPL 130228 The Case Against IPrefsnonameresearch100% (1)

- NN AAPL 130122 A For AppleDocument34 pagesNN AAPL 130122 A For ApplenonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN THEME 120930 ETP - Much Ado About NothingDocument15 pagesNN THEME 120930 ETP - Much Ado About NothingnonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN IJMLD 120828 Low Sales Growth A ConcernDocument6 pagesNN IJMLD 120828 Low Sales Growth A ConcernnonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN MPR 120730 Deserves More AirtimeDocument8 pagesNN MPR 120730 Deserves More AirtimenonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN THEME 120809 Gold I - Gold PrimerDocument24 pagesNN THEME 120809 Gold I - Gold PrimernonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN NESZ 120718 Pricey Consumer GiantDocument8 pagesNN NESZ 120718 Pricey Consumer GiantnonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN LMC 120801 Room For Capital RepaymentDocument8 pagesNN LMC 120801 Room For Capital RepaymentnonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN SPSB 120806 Property Downcycle RiskDocument12 pagesNN SPSB 120806 Property Downcycle RisknonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN STAR 120802 Still DirectionlessDocument9 pagesNN STAR 120802 Still DirectionlessnonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN GUIN 120801 Drink Moderately For NowDocument6 pagesNN GUIN 120801 Drink Moderately For NownonameresearchNo ratings yet

- NN MCIL 120802 Still A Good ReadDocument7 pagesNN MCIL 120802 Still A Good ReadnonameresearchNo ratings yet

- InvestAsian Investment Deck NewDocument14 pagesInvestAsian Investment Deck NewReidKirchenbauerNo ratings yet

- Macro Economics and Economic Development of PakistanDocument3 pagesMacro Economics and Economic Development of PakistanWaqas AyubNo ratings yet

- Banking - HL - CBA 0979 - GOROKAN (01 Jan 23 - 28 Feb 23)Document5 pagesBanking - HL - CBA 0979 - GOROKAN (01 Jan 23 - 28 Feb 23)Adrianne JulianNo ratings yet

- SS 2 SlidesDocument31 pagesSS 2 SlidesDart BaneNo ratings yet

- LTD Report Innocent Purchaser For ValueDocument3 pagesLTD Report Innocent Purchaser For ValuebcarNo ratings yet

- Alagappa University DDE BBM First Year Financial Accounting Exam - Paper2Document5 pagesAlagappa University DDE BBM First Year Financial Accounting Exam - Paper2mansoorbariNo ratings yet

- COM203 AmalgamationDocument10 pagesCOM203 AmalgamationLogeshNo ratings yet

- Bharti Airtel Services LTD.: Your Account Summary This Month'S ChargesDocument4 pagesBharti Airtel Services LTD.: Your Account Summary This Month'S ChargesVinesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Sanraa Annual Report 08 09Document49 pagesSanraa Annual Report 08 09chip_blueNo ratings yet

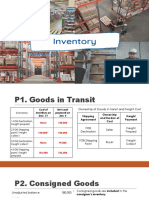

- Jawaban Soal InventoryDocument4 pagesJawaban Soal InventorywlseptiaraNo ratings yet

- CA. Ranjay Mishra (FCA)Document14 pagesCA. Ranjay Mishra (FCA)ZamanNo ratings yet

- Bfi AssignmentDocument5 pagesBfi Assignmentrobliao31No ratings yet

- IDirect Zomato IPOReviewDocument13 pagesIDirect Zomato IPOReviewSnehashree SahooNo ratings yet

- PT. Unilever Indonesia TBK.: Head OfficeDocument1 pagePT. Unilever Indonesia TBK.: Head OfficeLinaNo ratings yet

- Travis Kalanick and UberDocument3 pagesTravis Kalanick and UberHarsh GadhiyaNo ratings yet

- Croissance Economique Taux Change Donnees Panel RegimesDocument326 pagesCroissance Economique Taux Change Donnees Panel RegimesSalah OuyabaNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal On Challenges of Local GovernmentDocument26 pagesResearch Proposal On Challenges of Local GovernmentNegash LelisaNo ratings yet

- Cir Vs Metro Star SuperamaDocument2 pagesCir Vs Metro Star SuperamaDonna TreceñeNo ratings yet

- Total For Reimbursements: Transportation Reimbursements Date Transpo To BITSI March 23 To May 5, 2022Document4 pagesTotal For Reimbursements: Transportation Reimbursements Date Transpo To BITSI March 23 To May 5, 2022IANNo ratings yet

- Abaya vs. EbdaneDocument30 pagesAbaya vs. Ebdanealexandra recimoNo ratings yet

- P4 Taxation New Suggested CA Inter May 18Document27 pagesP4 Taxation New Suggested CA Inter May 18Durgadevi BaskaranNo ratings yet

- Cashback Redemption FormDocument1 pageCashback Redemption FormPapuKaliyaNo ratings yet

- Modifying Restrictive CovenantsDocument45 pagesModifying Restrictive CovenantsLonaBrochenNo ratings yet

- Formats Pensioners NHIS 2014Document4 pagesFormats Pensioners NHIS 2014Raj RudrapaaNo ratings yet

- The Land Acquisition Act 1894Document25 pagesThe Land Acquisition Act 1894Shahid Jamal TubrazyNo ratings yet