Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DCT Research

Uploaded by

pundungOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

DCT Research

Uploaded by

pundungCopyright:

Available Formats

Oct. 2008, Volume 5, No.10 (Serial No.

58)

Sino-US English Teaching, ISSN1539-8072, USA

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students

DUAN Ling-li, Anchalee Wannaruk

(School of English, Suranaree University of Technology, Nakhon Ratchasima 30000, Thailand)

Abstract: The present study is a comparison study of research instrument in the field of interlanguage pragmatics. Sixty-two Chinese EFL university students participated in the study. Written DCT and oral role-plays were designed in four stimulus types of refusal strategiesrefusals to invitations, suggestions, offers and requests. Chi-square test and frequency were used for quantitative data and transcription of the tests was used for the qualitative data. The results show that there is no significant difference between the two tests in terms of strategies choices, but written DCT can produce a longer sentence while oral role-plays can yield a more natural expression. Key words: written DCT; oral role-plays; English refusal strategies

1. Introduction

In the field of Interlanguage Pragmatics (ILP), there are mainly six types of measurements to assess pragmatic competence which can be conducted easily, i.e., Discourse Completion Tasks (DCTs), role-plays, multiple-choice questions, scaled-response questionnaires, interviews and think aloud protocols. The purpose of the present study is to compare DCT and role-plays in investigating English refusal strategies. A DCT item typically consists of a situational description followed by a brief dialogue, with (at least) one turn as an open slot to be completed by the participant (hence the term discourse completion). The specified context is designed to constrain the open turn(s) so that a specific communicative act is elicited. DCT has many administrative advantages: (1) It allows the researcher to control certain variables (i.e. age of respondents, features of the situation, etc); (2) It can quickly gather large amounts of data; (3) It is without any need for transcription, thus making it easy to statistically compare responses from native and non-native speakers; (4) Data elicited with DCTs are consistent with naturally occurring data, at least in the main patterns and formulas(Golato, 2003, p. 92). But DCT also has some disadvantages: (1) DCTs do not reflect real-time interactional sequences and are not a valid instrument for measuring pragmatic action, but symbolic action; (2) DCTs do not show the interactional facets of a speech event; (3) Research has shown that DCTs may be problematic in eliciting appropriate data from speakers of non-western languages (Golato, 2003, p. 93). Role-plays are simulations of communicative encounters based on role descriptions. Role-play can be defined as a social or human activity in which participants take on and act out specified roles, often within a predefined social framework or situational blueprint (a scenario) (Kasper & Rose, 2002, p. 86). In interlanguage pragmatics, a distinction has been made between closed and open role-play. In closed

DUAN Ling-li, Ph.D. candidate of School of English, Suranaree University of Technology; research fields: pragmatics and cross-cultural pragmatics. Anchalee Wannaruk, Dr., assistant professor of School of English, Suranaree University of Technology; research fields: pragmatics and cross-cultural pragmatics. 8

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students

role-play, the actors respond to the description of a situation, depending on the communicative act under study, and to an interlocutors standardized initiation. Open role-plays, on the other hand, specify the initial situation as well as each others role and goal(s) on individual role cards, but the course and outcome of the interaction are in no way predetermined (Kasper & Rose, 2002). Role-plays is capable of producing a wide array of interactional conducts, through the role specifications; an open role-plays provides more naturalistic data; role-play are online production tasks and thus have features similar to naturally occurring conversations (i.e. turning-taking, sequencing, hesitation phenomena, etc); it is easy to administer and allows for comparisons across dyads and allows for control of extra-linguistic variables such as power, status, gender, age, etc (Golato, 2003). However, it is predominantly motivated by the researchers goals rather than those of interactants. It is no guarantee that role-plays provide valid representations of pragmatic practices in authentic contexts. There may be discrepancies between the interactions in role-plays and in authentic discourse. Many ILP studies employ role-plays as an instrument of data collection. The rich potential of role-plays is evident from their use in L2 developmental pragmatics research on communicative acts such as requests (Hassall, 1997; Scarcella, 1979; Trosborg, 1995), complaints (Trosborg, 1995), apologies (Trosborg, 1995), greetings (Omar, 1991), gambits (Wildner-Bassett, 1984, 1986), routine formulae (Tateyama, 2001; Tateyama, Kasper, Mui, Tay & Thananart, 1997), pragmatic fluency (House, 1996), and interactionally appropriate responses to questions (Liddicoat & Crozet, 2001). But only a few studies have examined the validity of role-plays in interlanguage pragmatics. Edmondson & House (1991) found that nonnative speakers produced longer and more verbose utterances than native speakers on DCTs but not in role-plays. Eisenstein & Bodmans (1993) study compared the role of DCTs, open role-plays, and field note. All three types yielded the same words and expressions, yet they differed in length and complexity. The DCT data were the shortest and least complex, the authentic data and the longest and most complex, with the role-plays data coming in between. Based on the above background, the present study aims at examining the validity of written DCT and oral role-plays and finding out the difference between them. Therefore the research question is addressed as follows: Are there any differences between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigating four different types of English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students? If yes, in what aspects?

2. Participants

Two intact groups of first-year English majors from College of International Studies at Guizhou University, China participated in the study. Sixty-two valid data were collected. Based on the background information survey about participants, the average of age was 18.9. This suggests that the participants in the present study were almost equal to high school students because they just entered the university and the investigation began at the beginning of the first term. The average score of National Matriculation English Examination is 116.82 (out of 150) respectively. This indicates that the English level of the group is pre-intermediate. The average years of learning English could be evidence to their English level. The average years of learning English before entering the university was 6.85 years, and 53.2% subjects had learned English for six years and 30.6% subjects had learned English for seven years. Besides, nobody declared that they had been to English-speaking countries. Only one participant said he

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students

frequently spoke English with native speakers, but he had never learnt English refusal strategies from English native speakers and had never been to English-speaking countries. Therefore he was not excluded from the study. Though 12.9% participants had occasionally spoken to English native speakers, they also had never learnt English refusal strategies from English native speakers and had never been to English-speaking countries, so they were included in the study. And the majority of the participants (48.4% and 38.7%) declared that they rarely or never spoke English with native speakers.

3. Targets refusal strategies

Many English refusal strategies have been found in the previous studies. They include four stimulus types: refusing invitations, refusing suggestions, refusing requests and refusing offers. Each type includes three different statuses, i.e. refusing a person of higher status, refusing a person of equal status, refusing a person of lower status. The distance between the speakers and refusers is mainly between acquaintances or familiar persons. The present study adopts mainly Beebe, et al (1990), King & Silver (1993), Nelson, Al Batal & El Bakary (2002), Al-Issa (2003), Wannaruks (2004, 2005) research findings as a standard reference. The previous studies adopted mainly American English as a norm. Therefore, the present study takes the same norm as well. They are put in the following table (see Table 1).

Table 1 American top three frequently used refusal strategies Top three frequently used refusal strategies Status L-H Refusals to invitations E-E H-L L-H Refusals to suggestions E-E H-L L-H Refusals to offers E-E H-L L-H Refusals to requests E-E 1. Explanation 1. Explanation 1. Explanation 1. Explanation 1. Explanation 1. Explanation 1. Explanation 1. No 1. Give a comfort 1. Explanation 1. Explanation 2. Positive feeling 2. No 2. Gratitude 2. Alternative 2. Pause filler 2. Alternative 2. Gratitude 2. Gratitude 2. Alternative 2. Regret 3. Negative ability 3. Gratitude, future acceptance 3. Regret 3. Negative ability, pause filler 3. Positive feeling 3. Negative ability 3. Negative ability, positive feeling 3. Explanation 3. Regret 3. Alternative

Stimulus type

2. Letting the interlocutor off the hook.

H-L 1. Explanation 2. Regret 3. Positive feeling Notes: L-H means that a person of low status refuses a person from a high status; E-E means that the two speakers are in an equal status; H-L means that a person of high status refuses a person of low status. (Wannaruk, 2005)

4. Data collection

Based on Wannaruks (2005) four types of refusals, the types and format of written DCT are similar to her study with a slight modification. The situations for written DCT and oral role-plays are exactly the same so as to easily compare the results between the two tests. The only difference is that there is a background information survey for participants to provide in Chinese in written DCT (see Appendix). To validate the written DCT, some American native speakers, who were equal males and females in number and the age was 30-40, were invited to do the test to check whether the results were similar to the research findings in the previous studies. They helped to check the appropriate use of the rubrics in the written DCT as well. The written DCT was conducted before the

10

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students

oral role-plays. The time allotted for each test was 30 minutes. Respondents did it independently without discussion with their classmates. Participants were allowed to ask any questions if they were not clear. After the written DCT, the oral role-plays began. Before administering, participants were given detailed information about the role-plays procedures, including a guideline sheet. For each role-plays, participants were given a few minutes to read the role-plays cards and clarify any doubts related to vocabulary or the situation itself. No further guidance in respect to the target feature was provided at this point. All participants were told not to talk about the role-plays with their peers anytime during the project. The role-plays performances were audio-taped at all times. The interlocutors acting Role A, that is, invitor/suggestor/requestor/offeror, were selected among the American teachers at Guizhou University. Three of them were selected. The old one acted as a higher status person; the youngest one who was about 25 years old acted as the lower status person; the rest acted as the friends with an equal status. They were trained before the formal acting according to the guidelines for role-plays. They were required to act naturally so as to reduce the nerves of the students and tried to use the prompt expression designed for the role A. The participants and the American interlocutors worked attentively. The whole acting was recording. Some students were a little nervous, because this was the first time for them to be recorded and to face three English native speakers at the same time. When such situation happened, the researcher would not ask them to try until they thought they were no longer nervous. The present study got written DCT and oral role-plays data from 62 participants. The participants were asked to draw one type from the four stimulus types. Among 62 role-play, 14 subjects selected refusals to invitations, 17 for refusals to suggestions, 15 for refusals to offers and 16 for refusals to requests respectively. As to the transcription of written DCT and oral role-plays data, the criteria focus on the pattern of refusal strategies use. They can be found out according to the classification of refusals of Beebe, et al. (1990) which provides the most comprehensive and widely used taxonomy of the semantic formula for refusals to date. The second step was to figure out the intonation, pause, and turn which can embody the appropriateness of refusals to some extent. The criteria are the standards of transcription of conversation analysis.

5. The results

To answer the research question, refusal patterns or strategies are found in the data so as to see if the students can use the same as target strategies. Therefore, the comparison of the frequency of strategies used in written DCT and oral role-plays is a very good marker. After the categorization of different strategies, the frequency of the strategies was calculated. To see the difference between the frequencies of the two tests, Chi-square test was used for testing. According to Table 2, in general, there is no significant difference between written DCT and oral role-plays, because value is -1.55, p=.120>.05. Yet, only the type of refusals to offers has a significant difference, for value is-2.246, p=.024<.05. The following tables can illustrate this in detail.

11

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students

Table 2 Refusals type Invitations Suggestions Offers Requests Total Test DCT RP DCT RP DCT RP DCT RP DCT RP

Comparison of refusals strategies in written DCT and oral role-plays Mean 9.33 9.50 5.22 5.56 11.00 12.25 11.44 11.2 9.20 9.57 S.D. 4.96 5.08 6.91 6.62 3.46 7.32 3.50 3.63 5.26 5.39 -1.55 .120 9 -.106 .916 8 -2.246* .024 9 -.775 .439 N 9 -.412 Sig. .688

Note: * value is significant at the 0.05 level. Table 3 Frequency of refusals to invitations strategies in written DCT and oral role-plays Status L-H Target strategies 1. Positive feeling 2. Negative ability 3. Explanation E-E 1. No (Gratitude) 2. Future acceptance 3. Explanation H-L 1. Gratitude 2. Regret 3. Explanation Total Frequency in DCT Total (14) 12 (85.7%) 8 (57.1%) 14 (100%) 9 (64.2%) 2 (14.3%) 14 (100%) 10 (71.4%) 1 (7.1%) 14 (100%) 84 (66.7%) Frequency in RP Total (14) 14 (100%) 8 (57.1%) 14 (100%) 10 (71.4%) 0 14 (100%) 8 (57.1%) 4 (28.6%) 14 (100%) 86 (68.3%)

Table 3 is a summary table of refusals to invitation strategies used by 14 subjects in written DCT and oral role-plays. The table shows that in three statuses, the strategies used in written DCT and oral role-plays are almost consistent and they are very close to the targets strategies. The frequency of using explanation strategy is very high in three statuses with 14 (100%) in number. However, the second strategy in E-E and H-L status have a very low frequency with 2 (14.3%) and 0, and 1 (7.1%) and 4 (28.6%). That is to say, future acceptance and regret strategies are seldom used by the subjects. The following example can show the case.

DCT: Oh, I love to (positive), but I cant (negative), I have a lot of work to do. As you know, the final examination is coming (explanation). Role-plays: Id love to (positive), but I cant (negative), um I have to work; my final paper is due in two weeks (explanation).

The above example is No.1 student in a L-H status. The strategies used in written DCT and oral role-plays are almost the same. The only difference is a pause filler um in oral role-plays which is very common in an oral form. The second example is from No.60 student in an E-E status. The answers are almost the same. But comparing with the target strategies, both have no gratitude and future acceptance strategies. The example is as

12

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students

follows:

DCT: Hmm, no. You know Im busy in my work (explanation). Role-plays: No (No), you know (pause filler), Im busy in my business (explanation).

Through the analysis of refusing to invitations in three different situations, we can conclude that the strategies in L-H situation in written DCT and role-plays are almost the same as the target strategies. The strategies in E-E and H-L situation are not as good as the other statues, because the two strategies are the same and there is one variation.

Table 4 Status L-H Frequency of refusals to suggestions strategies in written DCT and oral role-plays Target strategies 1. Pause filler, negative ability 2. Explanation 3. Alternative E-E 1. Pause filler 2. Positive feeling 3. Explanation H-L 1. Negative ability 2. Explanation 3. Alternative Total Frequency in DCT Total (17) 2 (11.8%) 15 (88.2%) 0 0 0 17 (100%) 5 (29.4%) 15 (88.2%) 1 (5.9%) 55 (35.9%) Frequency in RP Total (17) 3 (17.6%) 16 (94.1%) 1 (5.9%) 2 (11.8%) 0 14 (82.4%) 2 (11.8%) 10 (58.8%) 1 (5.9%) 51 (33.3%)

Table 4 is a summary table of refusals to suggestions used by 17 subjects in written DCT and role-plays. The table shows that the strategies used in written DCT and oral role-plays are almost the same, the frequencies are 55 in DCT and 51 in role-plays which are not significantly different. But they are all different with the target strategies except explanation strategy which is used in three different statuses. Here is an example from No.58 in an E-E status:

DCT: Oh, no. I cant gain weight any more, because I feel so bad in my new clothes (explanation). Role-plays: Oh, no, I think I must (pause filler) I cant gain weight any more. I think, Ill Ill refuse any un incomfortable (negative). I want to try some new coat (negative).

Except explanation strategy, the other strategies are far away from the target strategies. In general, the strategies of refusals to suggestions in three different situations are not equal to the target strategies. Except explanation strategy, the other strategies used in the two tests are totally different from the target strategies. They did not perform well in strategies choices. Table 5 is a summary table of refusals to offers strategies used by 15 subjects in written DCT and role-plays. This table shows that the strategies that the students used in written DCT and role-plays are almost the same, especially in the H-L status. However, in L-H status, the second strategy is not popular among the students and is far away from the target strategies. Here is an example from No. 2 student in an E-E status. The strategies used in both tests are the same.

DCT: No. Thanks (gratitude). I can solve this problem by myself (explanation). Role-plays: No (No), thanks (gratitude), I can solve this problem by myself (explanation).

13

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students Table 5 Frequency of refusals to offers strategies in written DCT and oral role-plays Status L-H Target strategies 1. Positive feeling, negative ability 2. Gratitude 3. Explanation E-E 1. No 2. Gratitude 3. Explanation H-L Total 1. Giving a comfort 2. Letting the interlocutor off the hook Frequency in DCT Total (15) 11 (73.3%) 4 (26.7%) 13 (86.7%) 8 (53.3%) 11 (73.3%) 14 (93.3%) 15 (100%) 13 (86.7%) 84 (63.6%) Frequency in RP Total (15) 3 (17.6%) 4 (26.7%) 14 (93.3%) 10 (66.7%) 12 (80%) 14 (93.3%) 15 (100%) 14 (93.3%) 98 (72.6%)

Likewise, the case of refusals to requests is the same as the refusals to offer. From the following two tables, we can see that the performance of the students in the two tests is good and very close to the target strategies.

Table 6 Status L-H Frequency of refusals to requests strategies in written DCT and oral role-plays Target strategies 1. Regret 2. Explanation 3. Alternative E-E 1. Explanation 2. Regret 3. Alternative H-L 1. Positive 2. Regret 3. Explanation Total Frequency in DCT Total (16) 10 (62.5%) 16100 (%) 7 (43.8%) 15 (93.8%) 9 (56.3%) 9 (56.3%) 8 (50%) 15 (93.8%) 14 (87.5%) 103 (71.5%) Frequency in RP Total (16) 14 (87.5%) 16 (100%) 6 (37.5%) 15 (93.8%) 11 (68.8%) 8 (50%) 9 (56.3%) 8 (50%) 14 (87.5%) 101 (70.1%)

Table 6 is a summary table of refusals to requests strategies used by 16 students in the written DCT and oral role-plays of EG. This table shows that the strategies used in the posttest and role-plays are almost the same as the target strategies. The E-E and H-L situations are especially good, more than half of the students have the same strategies as the target strategies. Only L-H situation is not as good as the other two situations, because the use of alternative strategy is less than half of the students, only 7 in written DCT and 6 in role-plays. Here is a typical from No.34 student in an E-E status.

DCT: Im sorry (regret), but I need to use it for my homework (explanation), maybe some other can help you (alternative). Role-plays: Oh, sorry (regret), I need to do my homework (explanation), perhaps you may ask someone to help (alternative).

The strategies used in the written DCT and oral role-plays are almost the same as the target strategies. In terms of strategies choices, there is no significant difference in written DCT and oral role-plays. Yet, according to the transcription of the two kinds of data, there are some variations. Firstly, there are lots of pause

14

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students

fillers and broken sentences in oral role-plays while in written DCT the cases are reduced. For example, No. 36 student in L-H status of refusals to invitations perform a little different in the two tests. In written DCT the sentences are complete and there is no pause, but it has spelling mistake like Thans for thanks. But in oral role-plays there are two cases of pause filler and the sentence Id like is incomplete.

DCT: Id love to (positive), but I cant (negative). My final paper is due in two weeks (explanation). Thans for your invitation (gratitude). Role-plays: Oh, Id like Id love to (positive). Butum I have a lot of work to do (explanation). Thanks your invitation (gratitude).

Secondly, the sentences in oral role-plays tend to be shorter and more direct in comparing with the written DCT. Here is an example from No.2 student in an H-L status of refusals to invitations.

DCT: Thanks for your invitation (gratitude), but Im really busy now (explanation). Maybe next time (future alternative). Role-plays: Mm Im sorry (regret), I dont have time (explanation).

The sentences in oral role-plays are shorter and more direct in explaining I dont have time.

6. Discussion

Based on the above analysis, there is no obvious difference between the written DCT and oral role-plays in strategies choices. One of the reasons accounting for it is that the strategies in students mind are similar because they come from the same educational background. Another reason for it is that the situations in the two tests are exactly the same, their choices are limited and interaction can not be avoided. There is one previous study which got the same results as the present study but with some variations. Sasaki investigated two communicative acts, requests and refusals, administering DCT and role-play to Japanese EFL learners. Both methods elicited similar head acts and supportive moves for requests, and types and order of semantic formulae for refusals, but responses varied in length and content, with role-plays contributions featuring longer utterances and a greater variety of strategies (Kasper & Rose, 2002). The reason for the variations of the present study is that the students English level is not very high, therefore their sentences can not be long and complete. Or in other case, due to the low English level, their expressions can be redundant and have lot of repetitions. Rintell & Mitchell (1989) conducted a comparative study of written and oral DCTs (closed role-plays) administered to native and nonnative speakers of English, and found that the two types of data differed in two ways: non-native speaker oral responses were significantly longer than their written response, and in some situations both native speakers and non-native speakers were more direct than on the DCT than in the closed role-play. Marfalef-Boada (1993) examined the production of refusals by native speakers of German, Spanish, and German learners of Spanish. Due to the interactive nature of the role-plays and the multiple turns over which the refusal event evolved, the role-play were naturally longer, richer and more complex (Marfalef-Boada, 1993, p. 153) than the written single-turn responses. Furthermore, the present study also shows that the oral role-plays can elicit more natural sentences or expressions. That is why in some cases the students have pause fillers or repetitions. YUAN (2001) found that orally administering DCTs yields more naturalistic speech features than the equivalent written DCT.

7. Conclusions

15

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students

The present study aims at making a comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays. In general from the perspective of strategies choices, there is no significant difference between them, because their strategies use is similar with the target strategies. However, the comparison can show some variations. The oral role-plays produces more natural sentences with pause fillers, broken sentences or lengthy expressions. As non-native speakers, due to low English level, the sentences and expressions tend to be shorter when facing a native speaker. The written DCT yields more grammatical and complete but seems unnatural sentences. The present study partly supports some previous studies in validating research tool in the field of ILP. Therefore the study can be another discussion to the controversy of DCT and role-plays in ILP since DCT has been criticized and improvements are needed badly. Anyhow there are some limitations in the present study. The situations for the written DCT and oral play are exactly the same which may lead students to use the same strategies in the two tests. The further study needs some changes in the situation. Whats more, the number of participants is comparatively small, hence the results can not be a representative of similar study and at most a pre-study of a large scale study.

References: Al-Issa, A. 2003. Sociocultural transfer in L2 speech behaviors: Evidence and motivating factors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27, 581-601. Beebe, L. M., Takahashi, T. & Uliss-Weltz, R. 1990. Pragmatic transfer in ESL refusals. In: R. Scarcella, E. Anderson & S. Krashen. (Eds.), Developing communicative competence in a second language. New York: Plenum Press, 55-73. Edmondson, W. & House, J. 1991. Do learners talk too much? The waffle phenomenon in interlanguage pragmatics. In: R. Phillipson, E. Kellerman, L. Selinker, M. Sharwood Smith & M. Swain. (Eds.), Foreign second language pedagogy research. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters, 273-286. Eisenstein, M. & Bodman, J. W. 1993. Expressing gratitude in American English. In: G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka. (Eds.), Interlanguage pragmatics. New York: Oxford University Press, 64-81. Golato, A. 2003. Studying compliment responses: A comparison of DCTs and recordings of naturally occurring talk. Applied Linguistics, 1, 90-121. Hassall, T. J. 1997. Requests by Australian learners of Indonesian. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Australian National University, Canberra. House, J. 1996. Developing pragmatic fluency in English as a foreign language routines and metapragmatic awareness. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18, 225-252. Johnston, B., Kasper, G. & Ross, S. 1998. Effects of rejoinders in production questionnaires. Applied Linguistic, 19(2), 157-182. Kasper, G. & Rose, K. R. 2002. Pragmatic development in a second language. NJ: Blackwell, Mahwah Also Language Learning. Supplement 1, 52. King, K. A. & Silver, R. E. 1993. Sticking points: Effects of instruction on NNS refusal strategies. Working Papers in Educational Linguistics, 9, 47-82. Liddicoat, A. J. & Crozet, C. 2001. Acquiring French interactional norms through instruction. In: K. R. Rose & G. Kasper. (Eds.), Pragmatics in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 125-144. Margalef-Boada, T. 1993. Research methods in interlanguage pragmatics: An inquiry into data collection procedures. Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University. Dissertation Abstracts International, 233. Nelson, G. L., Al Batal, M. & El Bakary, W. 2002. Directness vs. indirectness: Egyptian Arabic and US English communication style. International Journal of International Relations, 26, 39-57. Omar, A. 1991. How learners greet in Kiswahili: A cross-sectional survey. Pragmatics and Language Learning, 2, 59-73. Urbana-Campaign: Division of English as an International Language, University of Illinois, Urbana-Campaign. Rintell, E., & Mitchell, C. J. 1989. Studying requests and apologies: An inquiry into method. In: S. Blum-Kulka, J. House & G. Kasper. (Eds.), Cross-cultural pragmatics. Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 248-272. Tateyama, Y. 2001. Explicit and implicit teaching of pragmatic routines: Japanese sumimasen. In: K. R. Rose & G. Kasper. (Eds.), Pragmatics in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 200-222. Tateyama, Y., Kasper, G., Mui, L., Tay, H. & Yhananrt, O. 1997. Explicit and implicit teaching of pragmatic routines. Pragmatics 16

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students and Language Learning, 8. Urbana-Campaign: Division of English as an International Language, University of Illinois, Urbana-Campaign. Trosborg, A. 1995. Interlanguage pragmatics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Wannaruk, A. 2004. Say No: A cross cultural comparison of Thais and Americans refusals. English Language Studies Forum, 1, 1-22. Wannaruk, A. 2005. Pragmatic transfer in Thai EFL refusals. Paper presented at the 13th Annual KOTESOL International Conference, Sookmyung Womens Unversity, and Seoul, Korea. Wilder-Bassett, M. 1984. Improving pragmatic aspect of learners interlanguage. Tubingen: Nar. Wilder-Bassett, M. 1986. Teaching and learning polite noises: Improving pragmatic aspects of advanced adult learners interlanguage. In: G. Kasper. (Ed.), Learning, teaching, and communication in the foreign language classroom. Arhus: Arhus University Press, 163-178. YUAN Y. 2001. An inquiry into empirical pragmatics data-gathering methods: Written DCTs, oral DCTs, field notes and natural conversations. Journal of Pragmatics, 33, 271-292. (in Chinese)

(Edited by Stella, Sunny and Max)

Appendix: Written DCT Part I: Background information survey Name____________ Class___________ Score of National Matriculation English Examination _______________ 1. How long have you learned English before you enter this university? 2. Have you ever learned American English refusal strategies? Yes__________ No______________ If yes, Where_______________________________________ How long____________ How many hours per week ________ 3. Have you ever been to Englishspeaking countries? Yes___________ No______________ If yes, where_________________ How long___________________ 4. How frequently do you speak English with native speakers? Frequently________ Occasionally________ Rarely_________ Never_________ Part II: Written DCT In this questionnaire, you will find several communication situations in which you interact with someone. Pretend you are the person in the situation. You must refuse all requests, suggestions, invitations, and offers. Write down your response. Respond as you would in an actual situation. 1. You are in your professors office talking about your final paper which is due in two weeks. Your professor indicates that he has a guest speaker coming to his next class and invites you to attend that lecture but you cannot. (Invitation: refusing to higher status) Your professor: By the way, I have a guest speaker in my next class who will be discussing issues which are relevant to your paper. Would you like to attend? You refuse by saying: 2. A friend invites you to dinner, but you really cant stand this friends husband/wife. (Invitation: refusing to equal status) Friend: How about coming over for dinner Sunday night? Were having a small dinner party. You refuse by saying: 3. You are a senior student in your department. A freshman, whom you met a few times before, invites you to lunch in the university cafeteria but you do not want to go. (Invitation: refusing to lower status) Freshman: I havent had my lunch yet. Would you like to join me? You refuse by saying: 4. You are at your desk trying to find a report that your boss just asked for. While you are searching through the mess on your desk, your boss walks over. (Suggestions: refusing to higher status) Boss: You know, maybe you should try and organize yourself better. I always write myself little notes to remind me of things. Perhaps you should give it a try! 17

The comparison between written DCT and oral role-plays in investigation upon English refusal strategies by Chinese EFL students You refuse by saying: 5. You are at a friends house watching TV. The friend recommends a snack to you. You turn it down, saying that you have gained weight and dont feel comfortable in your new clothes. Friend: Hey, why dont you try this new diet Ive been telling you about? It can make you lose weight. (Suggestions: refusing to equal status) You refuse by saying: 6. You are a language teacher at a university. It is just about the middle of the term now and one of your students asks to speak to you. Student: Ah, excuse me, some of the students were talking after class recently and we kind of feel that the class would be better if you could give us more practice in conversation and less on grammar. (Suggestion: refusing to lower status) You refuse by saying: 7. Youve been working in an advertising agency now for some time. The boss offers you a raise and promotion, but it involves moving. You dont want to go. Today, the boss calls you into his office. (Offer: refusing to higher status) Boss: Id like to offer you an executive position in our new office in Hicktown. Its a great townonly 3 hours from here by plane. And, a nice raise comes with the position. You refuse by saying: 8. You are going through some financial difficulties. One of your friends offers you some money but you do not want to accept it. (Offer: refusing to equal status) Your friend: I know you are having some financial difficulties these days. You always help me whenever I need something. I can lend you $20. Would you accept it from me? You refuse by saying: 9. You are at your home with your friend. You are admiring the expensive new pen that your father gave you. Your friend sets the pen down on a low table. At this time, your nanny goes past the low table, the pen falls on the floor and it is ruined. (Offer: refusing to lower status) Nanny: Oh, I am so sorry. Ill buy you a new one. You refuse by saying (Knowing she is only a teenager): 10. Your professor wants you to help plan a class party, but you are very busy this week. (Request: refusing to high status) Professor: We need some people to plan the class party. Do you think you can help? You refuse by saying: 11. A classmate, who frequently misses classes, asks to borrow your class notes, but you do not want to give them to him. (Request: refusing to equal status) Your classmate: You know I missed the last class. Could I please borrow your notes from that class? You refuse by saying: 12. You only have one day left before taking a final exam. While you are studying for the exam, one of your junior relatives, who is in high school, asks if you would help him with his homework but you cannot. (Request: refusing to lower status) Your relative: Im having problems with some of my homework assignments. Would you please help me with some of my homework tonight? You refuse by saying:

18

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- WBC Questions-MinDocument24 pagesWBC Questions-MinSomnath BiswalNo ratings yet

- Topic: Verbal::Worksheet Number:12Document3 pagesTopic: Verbal::Worksheet Number:12Sreejani BhaduriNo ratings yet

- Letter For Job Application - Google SearchDocument1 pageLetter For Job Application - Google SearchGigi Vera TaparNo ratings yet

- My ResumeDocument2 pagesMy ResumeSimon MuiruriNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning Strategies For Differentiated InstructionDocument23 pagesTeaching and Learning Strategies For Differentiated InstructionJoyce OrtizNo ratings yet

- The de Facto Inter-Domain Routing Protocol BGP Provides Each AS A Means ToDocument8 pagesThe de Facto Inter-Domain Routing Protocol BGP Provides Each AS A Means ToHassaan Rasheed FAST NU LHRNo ratings yet

- 10-Webinar Registration TemplateDocument5 pages10-Webinar Registration TemplatescottsdaleduilawyerNo ratings yet

- CV VerDocument3 pagesCV Verjoshsepe-1No ratings yet

- Writing (B1+ Intermediate) : English For LifeDocument13 pagesWriting (B1+ Intermediate) : English For LifeSuresh DassNo ratings yet

- Gsubp Guideline Apec RHSCDocument16 pagesGsubp Guideline Apec RHSCHsin-Kuei LIUNo ratings yet

- On Dell HymesDocument17 pagesOn Dell HymesFiktivni Fikus100% (1)

- Art Therapy and PsychoticDocument12 pagesArt Therapy and PsychoticcacaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Move Analysis of Literature ReviewDocument12 pagesTopic: Move Analysis of Literature Reviewsafder aliNo ratings yet

- List of The A.I Academic Study Centres (Secondary & SRDocument3 pagesList of The A.I Academic Study Centres (Secondary & SRagarwaalaaaa0% (1)

- ResearchDocument41 pagesResearchClifford NazalNo ratings yet

- Learning Game Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesLearning Game Lesson Planapi-269371029No ratings yet

- Classroom Management PlanDocument4 pagesClassroom Management Planapi-291516957No ratings yet

- Ict9 Group5 WrittenreportDocument2 pagesIct9 Group5 Writtenreportapi-293116810No ratings yet

- f1102 Gprs Intelligent Modem User ManualDocument30 pagesf1102 Gprs Intelligent Modem User ManualCocofourfaithNo ratings yet

- Marketing Exam Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument9 pagesMarketing Exam Multiple Choice Questionskarim100% (1)

- Four Types of Phonological Lenition in PDocument17 pagesFour Types of Phonological Lenition in POmnia Abd ElmonemNo ratings yet

- Buzibr Ns Positions & Detailed Job DescriptionDocument4 pagesBuzibr Ns Positions & Detailed Job Descriptionvikas babuNo ratings yet

- William Neal Clark CVDocument2 pagesWilliam Neal Clark CVapi-234468987No ratings yet

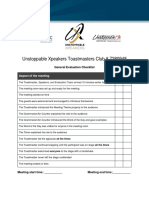

- Unstoppable Xpeakers Toastmasters Club EvaluationDocument3 pagesUnstoppable Xpeakers Toastmasters Club EvaluationJerry GreyNo ratings yet

- I Have, Who Has? Sight Word Practice: Learning ObjectivesDocument4 pagesI Have, Who Has? Sight Word Practice: Learning ObjectivesPrincess MadaniNo ratings yet

- TOEFL Score Report and Test Taker DetailsDocument2 pagesTOEFL Score Report and Test Taker Detailsiuppc 0No ratings yet

- Individual Work Plan SampleDocument3 pagesIndividual Work Plan SampleJohn Carter82% (17)

- MGB225 Assessment 1 CRA SUM2 2021Document1 pageMGB225 Assessment 1 CRA SUM2 2021StevenNo ratings yet

- Essay TopiDocument6 pagesEssay TopimanpreetNo ratings yet

- Acp 124Document96 pagesAcp 124TonyNo ratings yet