Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Calculations and Interpretations of 14 Key Financial Ratios

Uploaded by

warishaaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Calculations and Interpretations of 14 Key Financial Ratios

Uploaded by

warishaaCopyright:

Available Formats

Functions and Purposes of Financial Ratios

I. Functions of Financial Ratios Financial ratios can be used to show a companys: II. Position in its industry (industry comparisons) Accomplishment of objectives (objective comparisons) Vulnerability in the economy (time-series/trend analysis) Future borrowing power and growth potential (leverage ratios) Ability to react to unforeseen external changes (price/earnings ratio)

Types of Ratios and Their Purposes Profitability ratios indicate how well a company allocates its resources in relation to income generated. Liquidity ratios measure whether a company is able to pay its bills. Leverage ratios show how a companys operations are financed. Activity ratios measure a companys productivity and efficiency. Price/earnings (P/E) ratio reflects investors estimations of how well the company will be able to cope with unforeseen changes.

III.

Absolute Standards for Business Performance In many organizations, minimum financial ratios are used to serve as absolute standards for their performance as follows: Profitability: net profit no less than 3% Liquidity: current ratio greater than one Leverage: long-term debt to total equity less than one Activity: average collection period less than 60 days

IV.

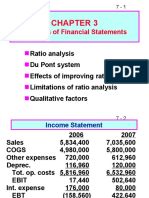

Trend Analysis of Selected Income Items During Last Five Years To analyze a companys performance trend, choose the companys 200x financial statement as a base year and then express subsequent items as percentages of their value in the base year. For example, consider the cost of goods sold item in successive income statements of ABC Company and use 1991 as a base year (100%), then you find a trend as shown in Table 1:

/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_3/135108963.doc 3/19/13 11:48 A3/P3

Table 1. Trend Analysis of ABC Companys Cost of Goods Sold from 1991-1995 Year 1991 $ in thousand $360,819 Percentage 100% 1992 $422,490 117.1% 1993 $498,901 138.3% 1994 $619,949 171.8% 1995 $728,861 202%

The following items are often selected for trend analysis with industry comparisons: Sales and other income Cost of goods sold Marketing, general, and administrative expenses

Calculations and Interpretations of 14 Key Financial Ratios

I. Fourteen Key Financial Ratios Return on Sales (Profit Margin) Return on Assets Return on Net Worth (Return on Equity) Quick Ratio Current Ratio Current Liabilities to Net Worth Current Liabilities to Inventory Total Liabilities to Net worth Fixed Assets to Net Worth Collection Period Sales to Inventory Assets to Sales Sales to Net Working Capital Accounts Payable to Sales

Profitability Ratios

Solvency (Liquidity) Ratios

Efficiency Ratios

II.

Calculate and Interpret Profitability Ratios 1). Return on Sales (Profit Margin) Return on Sales (Profit Margin) = Net Profit After Taxes/Annual Net Sales Interpretation: Return on sales (profit margin) is obtained by dividing net profit after taxes by annual net sales. This reveals the profit earned per dollar of sales and therefore measures the efficiency of the operation. Return must be adequate for the firm to be able achieve satisfactory profits for its owners. This ratio is an indicator of the firms ability to withstand adverse conditions such as falling prices, rising costs and declining sales.

/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_3/135108963.doc 3/19/13 11:48 A3/P3

2). Return on Assets Return on Assets = Net Profit After Taxes/Total Assets Interpretation: Return on assets comes from net profit after taxes divided by total assets. This ratio is the key indicator of profitability for a firm. It matches operating profits with the assets available to earn a return. Companies efficiently using their assets will have a relatively high return while less well-run businesses will be relatively low. 3). Return on Net Worth (Return on Equity) Return on Net Worth (Return on Equity) = Net Profit After Taxes/Net Worth Interpretation: Return on net worth (return on equity) is obtained by dividing net profit after tax by net worth. This ratio is used to analyze the ability of the firms management to realize an adequate return on the capital invested by the owners of the firm. Tendency is to look increasingly to this ratio as a final criterion of profitability. Generally, a relationship of at least 10 percent is regarded as a desirable objective for providing dividends plus funds for future growth. III. Calculate and Interpret Solvency (Liquidity) Ratios 4). Quick Ratio Quick Ratio = (Cash + Accounts Receivable)/Current Liabilities Interpretation: The Quick ratio is computed by dividing cash plus accounts receivable by total current liabilities. Current liabilities are all the liabilities that fall due within one year. This ratio reveals the protection afforded short-term creditors in cash near-cash assets. It shows the number of liquid assets available to cover each dollar of current debt. Any time this ratio is as much as 1 to 1 (1.0) the business is said to be in a liquid condition. The larger the ratio the greater the liquidity. 5). Current Ratio Current Ratio = Current Assets/Current Liabilities Interpretation: Current ratio comes from total assets divided by current liabilities. Current assets include cash, accounts and notes receivable (less reserves for bad debts), advances on inventories, merchandise inventories, and marketable securities. This ratio measures the degree to which current assets cover current liabilities. The higher the ratio the more assurance exists that the retirement of current liabilities can be made. The current ratio measures the margin of safety available to cover any possible shrinkage in the value of current assets. Normally a ratio of 2 to 1 (2.0) or better is considered good.

/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_3/135108963.doc 3/19/13 11:48 A3/P3

6). Current Liabilities to Net Worth Current Liabilities to Net Worth = Current Liabilities/Net Worth Interpretation: Current liabilities to net worth are derived by dividing current liabilities by net worth. This contrasts the funds that creditors temporarily are risking with the funds permanently invested by the owners. The smaller the net worth and the larger the liabilities, the less security for the creditors. Care should be exercised when selling any firm with current liabilities exceeding two-thirds (66.6 percent) of net worth. 7). Current Liabilities to Inventory Current Liabilities to Inventory = Current Liabilities/Inventory Interpretation: A dividing current liability by inventory yields another indication of the extent to which the business relies on funds from disposal of unsold inventories to meet its debts. This ratio combines with Net sales to Inventory to indicate how management controls inventory. It is possible to have decreasing liquidity while maintaining consistent sales-to-inventory ratios. Large increases in sales with corresponding increases in inventory levels can cause an inappropriate rise in current liabilities if growth isnt made wisely. 8). Total Liabilities to Net Worth Total Liabilities to Net Worth = Total Liabilities/Net Worth Interpretation: Total liabilities to net worth are obtained by dividing total current liabilities plus long-term and deferred liabilities by net worth. The effect of long-term (funded) debt on a business can be determined by comparing this ratio with Current Liabilities to Net Worth. The difference will pinpoint the relative size of long-term debt, which, if sizable, can burden a firm with substantial interest charges. In general, total liabilities shouldnt exceed net worth (100 percent) since in such cases creditors have more at stake then owners. 9). Fixed Assets to Net Worth Fixed Assets to Net Worth = Fixed Assets/Net Worth Interpretation: Fixed assets to net worth comes from fixed assets divided by net worth. The proportion of net worth that consists of fixed assets will vary greatly from industry to industry but generally a smaller proportion is desirable. A high ratio is unfavorable because heavy investment in fixed assets indicates that either the concern has a low net working capital and is over-trading or has utilized large funded debt to supplement working capital. Also, the larger the fixed assets, the bigger the annual depreciation charge that must be deducted from the income statement. Normally, fixed assets about

/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_3/135108963.doc 3/19/13 11:48 A3/P3

75 percent of net worth indicate possible over-investment and should be examined with care. IV. Calculate and Interpret Efficiency Ratios 10). Collection Period Collection period = Accounts Receivable/Sales X 365 days Interpretation: Collection period comes from accounts receivable divided by sales and then multiplied by 365 days. The quality of the receivables of a company can be determined by this relationship when compared with selling terms and industry norms. In some industries where credit sales are not the normal way of doing business, the percentage of cash sales should be taken into consideration. Generally, where most sales are for credit, any collection period more than one-third over normal selling terms (40.0 for 30- day terms) is indicative of some slow-turning receivables. When comparing the collection period of one concern with that of another, allowances should be made for possible variations in selling terms. 11). Sales to Inventory Sales to Inventory = Annual Net sales/Inventory Interpretation: Sales to inventory is obtained by dividing annual net sales by inventory. Inventory control is a prime management objective since poor controls allow inventory to become costly to store, obsolete or insufficient to meet demands. The sales-to-inventory relationship is a guide to the rapidity at which merchandise is being moved and the effect on the flow of funds into the business. This ratio varies widely between lines of business and a companys figure is only meaningful when compared with industry norms. Individual figures that are outside either the upper or lower quartiles for a given industry should be examined with care. Although low figures are usually the biggest problem, as they indicate excessively high inventories, extremely high turnovers might reflect insufficient merchandise to meet customer demand and result in lost sales. 12). Asset to Sales Asset to Sales = Total Assets/Net Sales Interpretation: Assets to sales is calculated by dividing total assets by annual net sales. This ratio ties in sales and the total investment that is used to generate those sales. While figures vary greatly from industry to industry, by comparing a companys ratio with industry norms it can be determined whether a firm is over-trading (handling an excessive volume of sales in relation to investment) or under-trading (not generating sufficient sales to warrant the assets invested). Abnormally low percentages (above the upper quartile) can indicate over-trading, which may lead to financial difficulties if not corrected. Extremely high percentages (below the lower quartile) can be the result of

/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_3/135108963.doc 3/19/13 11:48 A3/P3

overly conservative or poor sales management, indicating a more aggressive sales policy may need to be followed. 13). Sales to Net Working Capital Sales to Net Working Capital = Sales/Net Working Capital Interpretation: Net sales are divided by net working capital (net working capital is current assets minus current liabilities). This relationship indicates whether a company is over-trading or conversely carrying more liquid assets than needed for its volume. Each new industry can vary substantially and it is necessary to compare a company with its peers to see if it is either over-trading on its available funds or being overly conservative. Companies with substantial sales gains often reach a level where their working capital becomes strained. Even if they maintain an adequate total investment for the volume being generated (assets to sales), that investment may be so centered in fixed assets or other non-current items that it will be difficult to continue meeting all current obligations without additional investment or reducing sales. 14). Accounts Payable to Sales Accounts Payable to Sales = Accounts Payable/Annual Net Sales Interpretation: Accounts payable to sales is computed by dividing accounts payable by annual net sales. This ratio measures how the company is paying its suppliers in relation to the volume being transacted. An increasing percentage, or one larger than the industry norm, indicates the firm may be using suppliers to help finance operations. This ratio is especially important to short-term creditors since high percentage could indicate potential problems in paying vendors.

/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_3/135108963.doc 3/19/13 11:48 A3/P3

You might also like

- ABM-BUSINESS FINANCE 12 - Q1 - W1-W2 - Mod1 PDFDocument17 pagesABM-BUSINESS FINANCE 12 - Q1 - W1-W2 - Mod1 PDFKaren Lacuban77% (26)

- Financial Statement Analysis Problem SolutionsDocument35 pagesFinancial Statement Analysis Problem SolutionsMaria Younus78% (9)

- 7 CMA FormatDocument22 pages7 CMA Formatzahoor80100% (2)

- Due - Diligence Checklist - IPO (BOBCAP)Document42 pagesDue - Diligence Checklist - IPO (BOBCAP)vbhammer100% (2)

- Understanding Financial Statements (Review and Analysis of Straub's Book)From EverandUnderstanding Financial Statements (Review and Analysis of Straub's Book)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- What Is A Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Literature ReviewwarishaaNo ratings yet

- Working Capital Management in BhelDocument86 pagesWorking Capital Management in BhelDipesh Gandhi100% (1)

- Sun Life Final PaperDocument53 pagesSun Life Final PaperAnonymous OzWtUONo ratings yet

- About Financial RatiosDocument6 pagesAbout Financial RatiosAmit JindalNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document27 pagesModule 2MADHURINo ratings yet

- Ulas in Customer Financial Analysis: Liquidity RatiosDocument9 pagesUlas in Customer Financial Analysis: Liquidity RatiosVarun GandhiNo ratings yet

- Types Financial RatiosDocument8 pagesTypes Financial RatiosRohit Chaudhari100% (1)

- Analyzing Financial Statements and RatiosDocument17 pagesAnalyzing Financial Statements and Ratiosanonymathieu50% (2)

- Chap 3 Problem SolutionsDocument31 pagesChap 3 Problem SolutionsAhmed FahmyNo ratings yet

- Price Earning (P/E) RatioDocument8 pagesPrice Earning (P/E) RatioKapilNo ratings yet

- FM NotesDocument15 pagesFM NotesEbsa AdemeNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument7 pagesFinancial Ratio AnalysisGalibur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Chap 6 (Fix)Document13 pagesChap 6 (Fix)Le TanNo ratings yet

- Ratios and Formulas in Customer Financial AnalysisDocument10 pagesRatios and Formulas in Customer Financial Analysisxmuhammad_ali100% (1)

- Chapter 3 Solutions & NotesDocument17 pagesChapter 3 Solutions & NotesStudy PinkNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratios Guide for Customer AnalysisDocument11 pagesFinancial Ratios Guide for Customer AnalysisPrince Kumar100% (1)

- BCOM 111 Topic Analysis and Interpretation of Financial StatementsDocument13 pagesBCOM 111 Topic Analysis and Interpretation of Financial Statementskitderoger_391648570No ratings yet

- Financial Ratios End TermDocument11 pagesFinancial Ratios End TermPriyanka Roy100% (1)

- Importance of Financial StatementDocument11 pagesImportance of Financial StatementJAY SHUKLANo ratings yet

- Financial Ratios Liquidity Ratios: Working CapitalDocument9 pagesFinancial Ratios Liquidity Ratios: Working CapitalLen-Len CobsilenNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Key Financial RatiosDocument31 pagesAnalysis of Key Financial RatiosMaxhar AbbaxNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Financial Statements: Answers To Selected End-Of-Chapter QuestionsDocument9 pagesAnalysis of Financial Statements: Answers To Selected End-Of-Chapter Questionsfeitheart_rukaNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument8 pagesFinancial Ratio AnalysisSyeda AtikNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 (14 Ed) Analysis of Financial StatementsDocument25 pagesChapter 3 (14 Ed) Analysis of Financial StatementsSOHAIL TARIQNo ratings yet

- What Does Capital Expenditure - CAPEX Mean?Document5 pagesWhat Does Capital Expenditure - CAPEX Mean?saber21chatterjeeNo ratings yet

- BE Sols - FM14 - IM - Ch3Document25 pagesBE Sols - FM14 - IM - Ch3ashibhallauNo ratings yet

- Corporate Banking - Updates RatiosDocument15 pagesCorporate Banking - Updates RatiosLipika haldarNo ratings yet

- Short-term Solvency and Liquidity Ratios GuideDocument18 pagesShort-term Solvency and Liquidity Ratios GuideSachini Dinushika KankanamgeNo ratings yet

- Accounting Ratio'sDocument26 pagesAccounting Ratio'sRajesh Jyothi100% (1)

- Liquidity Ratios:: Current Ratio: It Is Used To Test A Company's LiquidityDocument12 pagesLiquidity Ratios:: Current Ratio: It Is Used To Test A Company's LiquidityDinesh RathinamNo ratings yet

- Financial ratios and conceptsDocument12 pagesFinancial ratios and conceptssimon berksNo ratings yet

- Ratio Analysis: RatiosDocument6 pagesRatio Analysis: RatiosDasun LakshithNo ratings yet

- Corporate Banking - Updates RatiosDocument13 pagesCorporate Banking - Updates RatiosDisha NangiaNo ratings yet

- Workbook On Ratio AnalysisDocument9 pagesWorkbook On Ratio AnalysisZahid HassanNo ratings yet

- Ratio Analysis - Tata and M Amp MDocument38 pagesRatio Analysis - Tata and M Amp MNani BhupalamNo ratings yet

- EFim 05 Ed 2Document18 pagesEFim 05 Ed 2Hira Masood100% (1)

- Fatema NusratDocument10 pagesFatema NusratFatema NusratNo ratings yet

- Chapter5 Summary Financial Statement Analysis IIDocument9 pagesChapter5 Summary Financial Statement Analysis IIElvie Abulencia-BagsicNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Financial Statements - Ratio AnalysisDocument10 pagesInterpretation of Financial Statements - Ratio AnalysisDeepalaxmi Bhat100% (1)

- Banking ReviewerDocument4 pagesBanking ReviewerRaymark MejiaNo ratings yet

- Financial RatiosDocument21 pagesFinancial RatiosAamir Hussian100% (1)

- Financial Strategic MeasuresDocument17 pagesFinancial Strategic MeasuresVIVEK KUMARNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Solution ManualDocument14 pagesChapter 3 Solution ManualAhmed FathelbabNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratio Analysis-IIDocument12 pagesFinancial Ratio Analysis-IISivaraj MbaNo ratings yet

- Tata Motors.: Liquidity RatiosDocument11 pagesTata Motors.: Liquidity RatiosAamir ShadNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Financial Statements: Answers To End-Of-Chapter QuestionsDocument15 pagesAnalysis of Financial Statements: Answers To End-Of-Chapter QuestionsAditya R HimawanNo ratings yet

- FINDEFA4Document7 pagesFINDEFA4Shahnawaz ChunawalaNo ratings yet

- Financial analysis ratiosDocument30 pagesFinancial analysis ratiosRutuja KhotNo ratings yet

- Performance of A Company?: How To Deal With Questions On Assessing TheDocument5 pagesPerformance of A Company?: How To Deal With Questions On Assessing TheABUAMMAR60No ratings yet

- MIRANDA, ELLAINE - FM - 2021 - ST - Session 3 OutputDocument9 pagesMIRANDA, ELLAINE - FM - 2021 - ST - Session 3 OutputEllaine MirandaNo ratings yet

- IoratDocument3 pagesIoratRasha Srour KreidlyNo ratings yet

- Accounting for Managers Final Exam RatiosDocument7 pagesAccounting for Managers Final Exam RatiosGramoday FruitsNo ratings yet

- Ratio Analysis: 2.1 Liquidity RatiosDocument8 pagesRatio Analysis: 2.1 Liquidity RatiosRifat HasanNo ratings yet

- Coop Banking UpdatesDocument6 pagesCoop Banking UpdatesKBDP AND CO.No ratings yet

- Financial Analysis FundamentalsDocument12 pagesFinancial Analysis FundamentalsAni Dwi Rahmanti RNo ratings yet

- Financial RatiosDocument4 pagesFinancial RatiosSrinivasa RaoNo ratings yet

- FIN 300 Chapter 3 Analysis of Financial StatementsDocument9 pagesFIN 300 Chapter 3 Analysis of Financial StatementsJean EliaNo ratings yet

- Current RatioDocument22 pagesCurrent RatioAsawarNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratios Analysis and InterpretationDocument8 pagesFinancial Ratios Analysis and InterpretationChristian Zebua75% (4)

- Ratio Analysis Notes: Liquidity RatiosDocument7 pagesRatio Analysis Notes: Liquidity RatiosShaigari VenkateshNo ratings yet

- CH 03 SolDocument4 pagesCH 03 Solbhavin_tannaNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomic TrendsDocument4 pagesMacroeconomic TrendswarishaaNo ratings yet

- BenefitsDocument1 pageBenefitswarishaaNo ratings yet

- 36Document9 pages36warishaaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Financial StatementsDocument46 pagesAnalysis of Financial StatementsJim GohNo ratings yet

- Stats ProjectDocument14 pagesStats ProjectwarishaaNo ratings yet

- PAK ECO SlidesDocument13 pagesPAK ECO SlideswarishaaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Starbucks Delivering Customer ServiceDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Starbucks Delivering Customer ServicewarishaaNo ratings yet

- CBHTS Dept of Econ, Banking & Finance BNK 603 Banking Operations & Management QuestionsDocument4 pagesCBHTS Dept of Econ, Banking & Finance BNK 603 Banking Operations & Management QuestionswarishaaNo ratings yet

- Vertical AnalysisDocument1 pageVertical AnalysiswarishaaNo ratings yet

- UnemploymentDocument6 pagesUnemploymentwarishaaNo ratings yet

- A Critique of The Asset Pricing TheoryDocument2 pagesA Critique of The Asset Pricing TheorywarishaaNo ratings yet

- BenefitsDocument1 pageBenefitswarishaaNo ratings yet

- Time Table MBA IDocument1 pageTime Table MBA IwarishaaNo ratings yet

- Rational MarketsDocument25 pagesRational MarketswarishaaNo ratings yet

- Economy of NigeriaDocument35 pagesEconomy of NigeriawarishaaNo ratings yet

- Agor Oil IndustryDocument17 pagesAgor Oil IndustryNirankar SinghNo ratings yet

- Ratio Analysis of Sainsbury PLCDocument4 pagesRatio Analysis of Sainsbury PLCshuvossNo ratings yet

- Teknosa 4 QengDocument15 pagesTeknosa 4 QengFaIIen0nENo ratings yet

- EASEMYTRIP - Investor Presentation - 06-Feb-23Document26 pagesEASEMYTRIP - Investor Presentation - 06-Feb-23Karan GoelNo ratings yet

- BMG704 Practice 1 Quiz AnswersDocument5 pagesBMG704 Practice 1 Quiz AnswersJawad KaramatNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis of Metrolla Steels LtdDocument70 pagesFinancial Analysis of Metrolla Steels LtdJosemon Paulson100% (1)

- Wipro Analysis Final PDFDocument45 pagesWipro Analysis Final PDFDARSHANANo ratings yet

- Project Report On Working Capital ManagementDocument5 pagesProject Report On Working Capital ManagementdeeptanshuranjansharmaNo ratings yet

- Cash Management Analysis ProjectDocument78 pagesCash Management Analysis Projectshailesh100% (1)

- Ratio AnalysisDocument7 pagesRatio AnalysisRam KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Working Capital Management in Aluminium Sector: A Case Study of NALCODocument11 pagesWorking Capital Management in Aluminium Sector: A Case Study of NALCOShareNo ratings yet

- Khalid Siraj Textile Mills Limited Company InformationDocument6 pagesKhalid Siraj Textile Mills Limited Company InformationDani zNo ratings yet

- Smart Task 2 OF Project Finance by (Vardhan Consulting Engineers)Document8 pagesSmart Task 2 OF Project Finance by (Vardhan Consulting Engineers)devesh bhattNo ratings yet

- For Print Gopal NamkeenDocument90 pagesFor Print Gopal NamkeenPinkesh Mishra Prins92% (12)

- Cash Flow Statement: by B.K.VashishthaDocument20 pagesCash Flow Statement: by B.K.VashishthaNadya Shamini100% (1)

- Advance Financial Management: Unit - IDocument74 pagesAdvance Financial Management: Unit - IShivam Thakur 5079No ratings yet

- Cost Accounting - Group 9Document45 pagesCost Accounting - Group 9aditya mehtaNo ratings yet

- Establishing an Oral Rehydration Salt PlantDocument25 pagesEstablishing an Oral Rehydration Salt PlantJohn50% (2)

- MCQ Management Accounting B Com Sem 6 1Document30 pagesMCQ Management Accounting B Com Sem 6 1Ali HassanNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument34 pagesResearch ProposalSimon Muteke100% (1)

- Marketing FinanceDocument181 pagesMarketing FinanceAshwini PatadeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Financial Statement Analysis ExercisesDocument6 pagesChapter 3 Financial Statement Analysis ExercisesCatherine VenturaNo ratings yet

- ACG2071 Managerial AccountingDocument40 pagesACG2071 Managerial AccountingJadeNo ratings yet

- MRF Corporate Finance ProjectDocument24 pagesMRF Corporate Finance ProjectAneesh GargNo ratings yet

- Business Valuation Approaches ExplainedDocument12 pagesBusiness Valuation Approaches ExplainedGrigoras Alexandru NicolaeNo ratings yet