Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Parabola Book

Uploaded by

Muhd Zahimi Mohd NoorCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Parabola Book

Uploaded by

Muhd Zahimi Mohd NoorCopyright:

Available Formats

THE PARABOLAModern History

THE PARABOLA Kensington High Street

THE PARABOLA Kensington High Street

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Sir Stuart Lipton VISION & PRINCIPLES THE PARABOLA SITE PLAN Project Essays THE SPIRIT OF THE TIME by Lord Cunliffe of Headley A leading member of the original architectural team in 1958 MODERN HISTORY by Reinier de Graaf Partner of the Ofce for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) URBAN SCULPTURE by Paul Finch The Architectural Review DESIGN MUSEUM by Deyan Sudjic Director, The Design Museum CONTACTS & TEAM 16 01

INTRODUCTION Renovating a neglected wonder Sir Stuart Lipton Chelseld Partners 02 14 When we purchased the site of the former Commonwealth Institute we saw the opportunity of bringing back to life the essence of the original concept with the Parabola at its heart. The Parabola, the tent like structure, has been empty for nearly ten years and it deserves a new life. Our vision is to place the Parabola as a cherished piece in the context of new buildings designed in the same spirit of boldness and ingenuity that was the basis of the Parabolas design thesis. The Parabolas initial construction was bold for 1960 with a hyperbolic paraboloid roof. Designs at the time only permitted half of the concrete roof construction to be built with the remaining roof built traditionally. The leanness of the original budget will be in sharp contrast to the quality proposed for the refurbishment of the building. The site is demanding; Kensington High Street is facing competition from a new shopping centre at White City, the historical context and the beauty of Holland Park have to be respected. We commissioned an architectural competition with a number of experts as panel members and chose OMA as architects based on their design skill and commitment to revitalising the Parabola.

18

After two years of ownership and a forensic examination of the site we feel ready to make a planning application. The new buildings form and shape respect the Parabola and give it greater impact within its surroundings. They respond to the original design concepts of boldness which the Parabola brought to Kensington. The Design Museum has worked closely with us to enable it to occupy the Parabola with internal changes which allow the external image of the building to remain virtually unchanged with an interior that ts the Museums goals for the future. The landscape is designed by West 8 architects and reects both the spirit of the existing park and a new idiom engulng the three residential buildings. The project will take its place in the revitalisation of Kensington High Street bringing 400,000 people annually to the museum and renovating a neglected wonder to resume its iconic position on the High Street.

20

22

24

01The Parabola

VISION & PRINCIPLES

THE EXHIBITION BUILDING

The Design Museum will bring 400,000 visitors to the Parabola, giving a neglected London icon new life and purpose.

03The Parabola

THE RESIDENTIAL BUILDINGS

The new buildings continue the modern spirit of the original, but are deliberately neutral so that the Parabola is dominant.

04The Parabola

KENSINGTON HIGH STREET

The High Street is re-connected to the Parabola. The new buildings and restoration will bring residents, business and new possibilities to the area.

06The Parabola

THE PARK

The tent in the park will be a cultural destination for London and Europe. It will celebrate innovation and design of the highest calibre.

10The Parabola

STONE FACADES

World class architecture will continue the tradition of modernity, respecting the past and creating a sustainable future.

13The Parabola

THE PARABOLA SITE PLAN

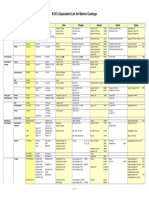

THE EXHIBITION BUILDING To be occupied by the Design Museum The building will be refurbished and renovated 100,000 sq ft oorspace Intended uses: exhibition; events; restaurant and caf; auditorium and education; shop; ofces; workshops THE HIGH STREET BUILDING Commercial ground oor + 7 oors of residential units Ground oor uses: facilities associated with the Design Museum including exhibition area, shop and tickets; and a shop or restaurant and caf 23 residential units

THE GARDEN BUILDING 9 oors 38 residential units THE PARK BUILDING 6 oors 11 residential units

PARK

EXHIBITION

HIGH STREET

GARDEN

15The Parabola

THE SPIRIT OF THE TIME Reections on 1958 Roger CunliffeLord Cunliffe of Headley A leading member of the original architectural team We post-war British architects were inspired to build a brave new world: egalitarian, intelligent, refreshing and humane. But right into the late 1950s, when this project began, we were still constrained by having to meet a huge demand, with limited resources. The resulting architecture was strongly focused on the users. It had to be t for the immediate purpose simply that. Future reuse was not our foremost thought. Since then, as an organisation the Commonwealth Institute has adapted to a rapidly changing world, but the building has been unable to keep up. Some years back it was abandoned: no one could nd a conventional way of keeping it viable, even in a period of building boom. Something more radical more innovative was needed. Two years ago the Ilchester Estate and Chelseld acquired the site. There was a market review and thorough research of the complexs history. Chelseld then invited six eminent architectural rms to discuss proposed approaches to the challenge, and selected OMA, an internationally renowned Dutch rm which already had other projects in Britain.

The OMA concept is simple and restrained, but bold where necessary. Constructive discussions with English Heritage, The Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea and others have advanced the design, but without compromising its integrity. Opportunities not available to us fty years ago have been seized. That is rare and valuable. Even for the time, the project had a niggardly budget. So our priorities had to be rst the exhibition building, then the ancillary wing, and last the landscape. The design had to be pared to the minimum. Standards for access, health and safety and energy conservation were also much lower then. On all counts a major upgrading is now needed. Because of its size we had to place the exhibition building at the back of the site, angled to preserve the ne lime trees along the boundary. With its hypar roof, it became the tent in the park, though the immovable boundary wall blocked a full union. The building was also hard to see from the High Street. Renewal calls for resources. The Chelseld team is of the highest calibre. The authorities and the public have expressed their views; all want to see the complex brought to life again. No one under-rates the task. But it will cost money, and the new development on the site will generate that. This time the budget must not be skimped. The Commonwealth Institute complex embodied the spirit of the time. I feel strongly that this aspect of its cultural heritage adventure, innovation, can-do should be respected by what comes next. OMAs proposals hearten me. Whilst they demonstrate the way cities are evolving in the 21st century, they are also in tune with the spirit of the buildings creation.

17The Parabola

MODERN HISTORY Reinier de GraafOMA Partner of the Ofce for Metropolitan Architecture Building in an urban context means respecting history. But, if the course of history is a sequence of different (often clashing) periods, what does one pay respect to? As architects we have often wondered if rather than preserving buildings or urban environments in their original state, paying respect should actually constitute the continuation of an evolution, which could lead to the improvement (or even correction) of a given context. The Former Commonwealth Institute seems to provide a unique opportunity in that direction. Built in the early 1960s, it represents a still undigested period of our architectural history. The sixties are history without (yet) enjoying the respect normally paid to history. At the same time, experiments like the former Commonwealth Institute continue to inspire the work of many architects today (including our own). About a year ago, as part of a limited competition to choose an architect, we presented our rst proposals for the site. The idea was simple: to retain the main exhibition building, demolish the administration wing, and to ll the remaining spaces with three residential blocks as the new setting for the main building, now re-named as the Parabola.

We decided to orient the new buildings the same way as the Parabola: 45 degrees to the prevailing orientation of the urban fabric around it. From our rst acquaintance with the site there was something intriguing and mystical about the exhibition buildings orientation, deliberately at odds with its surroundings, even partly at odds with itself almost like an Islamic fragment that mysteriously got lost in this part of West London. We were all too aware that paying respect to and even reproducing a feature that at the time of its conception constituted a deliberate break with its surroundings would almost automatically create a risk of also reproducing the buildings perceived contextual indifference. The style and shape of the three new buildings are unequivocally modern: three cubes as a deliberate, neutral background, allowing the Parabola to be the main feature on display. However, whilst the orientation and the square footprint of the new buildings echo the Parabola, they also, through variations in footprint and height like Russian dolls echo the different scales of the surrounding context. In its new conguration the Commonwealth Institute is no longer a singular building, but part of a larger ensemble. As much individual objects as urban fabric, the new buildings tie the Parabola into the city (albeit retroactively). In their new setting the Parabola and its surroundings are no longer opposite ends of the spectrum, but integral parts of a new balance between the recent and older history of this part of London.

18The Parabola

URBAN SCULPTURE Paul Finch The Architectural Review London is, on the whole, an unplanned city. But the British obsession with heritage means that the accidental or the informal can take on the status of the planned, to be respected and acknowledged in spite of (or perhaps even because of) a particular history. Thus it is with the Parabola. The sites main virtue at the time of construction was availability, plus proximity to the old Imperial Institute. The design itself represented a combination of functionalism, lightweight construction and modernity, a contemporary response as different as possible to the heavyweight Imperial Institute it replaced. OMAs proposition makes sense of the site. The composition of the three apartment buildings, and what will become the new home for the Design Museum, produces a piece of urban sculpture, unusual in London and only possible because of the history of this site. It is many years since London saw the planned creation of an arts building along with a residential development. The last occasion, albeit on a much larger scale, was the Barbican in the City of London. Unlike the Barbican, the Kensington High Street site will not be sealed off from the street, but will create an inviting new environment; and unlike the Barbican, it is not reliant on its own landscape (though this will form an important part of the development) but has a major relationship with Holland Park next door.

The architectural approach has to deal with very different conditions in relation to aspect and prospect, differing scales, a break in the conventional street elevation, access to a gem of a park, and of course to the memory of the site and its key building. The design will provoke discussion; do the new blocks genuect too much to that accidental original site planning? How do they relate to adjacent residential mansion blocks? What is the relationship to the park, and so on. These are the commonplaces of architectural debate and discussion, but are no less important for that. In the case of OMA, the generation of the proposal has come from a profound understanding of architectural relationships. They understand very well the importance of focusing on the essential and not becoming overwhelmed by the challenge of combining the contemporary with the historical. What was for two decades an urban problem is at last a focus for new purpose a new architectural lease of life.

21The Parabola

DESIGN MUSEUM Deyan Sudjic Director, The Design Museum After twenty successful years in Southwark the Design Museum is ready to move to the next stage in its development. A bigger, better Design Museum will give London a focus for exploring design and architecture. More than just a tourist attraction, it will be a place that will change the way the world understands design. And if it can do that it will change the way the world sees London. Twenty years ago Sir Terence Conran established the museum as a project within the Victoria and Albert Museum and subsequently gave it a building of its own. He believed it was time to remind Britain that design was more than a matter of aesthetics. Design in the museums view depends on an understanding of the complex process that turns an idea into a manufactured object. Today around 240,000 visitors come to the museum every year. The museum is always brimming with people: children learning how to make a model in the education centre; exhibition visitors getting inside the mind of an architect such as Zaha Hadid, a fashion designer like Hussein Chalayan, or a graphic designer of the calibre of Alan Fletcher. Look behind the scenes and you will nd our collection, a record of the key designs that have made the modern world.

The Parabola will solve the museums most pressing problem: lack of space. With three times as much space, the museum will have more room for exhibitions, to display its permanent collection and to run an exciting programme of public engagement. Our studies suggest we can attract an audience of 400,000 visitors a year. The opportunity is one we cannot miss. What makes the the Parabola so exciting as a new home for the Design Museum is that it will allow us to create a new kind of museum, by giving a new lease of life to a key landmark from the 1960s. It is the chance to bring an important listed building with a troubled past back into use for the long term. In the last decade the concept of transforming a 19th century industrial building into a contemporary cultural space has become a conventional response. The Parabola offers the chance to go much further and seize the opportunity to redene the nature of a cultural space. As Britain comes to understand that its economic future lies in the creative industries, design is more important than ever. An expanded Design Museum is set to play a vital role in making the most of the contribution that design can make to the economy and society at large. The new Design Museum will consolidate Londons claim to be a worldwide hub for design.

22The Parabola

THE PARABOLA Kensington High Street

2009 IIchester Estates & Chelseld Partners

WWW.CHELSFIELD.COM WWW.THEPARABOLA-KENSINGTON.CO.UK

Contact

The project team

CHELSFIELD PARTNERS Telephone +44 (0)20 7290 2388 enquiries@chelseld.com 67 Brook Street London W1K 4NJ

ARCHITECT Ofce for Metropolitan Architecture ARCHITECTURAL CONSULTANT Lord Cunliffe of Headley LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT West 8 STRUCTURAL ENGINEER Arup SERVICES ENGINEER Arup

TRANSPORT CONSULTANT Arup SUSTAINABILITY CONSULTANT Arup ACCESSIBILITY CONSULTANTS David Bonnet Associates PLANNING CONSULTANT DP9 HERITAGE CONSULTANT Montagu Evans ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANT RPS

DAYLIGHT/SUNLIGHT CONSULTANT GIA CONSTRUCTION CONSULTANTS Mace COMMUNITY RELATIONS Four Communications George Cochrane PUBLIC RELATIONS Bolton & Quinn

24The Parabola

THE PARABOLA Kensington High Street

IMAGE CREDITS Page 16 Henk SnoekRIBA Library Photographs Collection DESIGNED BY Small Unit 9 16-30 Provost Street London N1 7NG Telephone +44 (0)20 7490 1049 www.studiosmall.com PRINTED IN THE UK BY The Good News Press Telephone +44 (0)1277 362106 www.goodnewspress.co.uk

You might also like

- Alexandria LibraryDocument62 pagesAlexandria LibraryTmt TarekNo ratings yet

- Colocviu EnglezaDocument2 pagesColocviu EnglezaLivia Liv100% (1)

- Art Gallery of Alberta by Randall Stout ArchitectsDocument3 pagesArt Gallery of Alberta by Randall Stout ArchitectsJoelChristianChandraNo ratings yet

- Archetype - MagazineDocument34 pagesArchetype - MagazineCory SmitNo ratings yet

- 6 - Metropol Parasol 2Document16 pages6 - Metropol Parasol 2AnshikaSrivastavaNo ratings yet

- CEDRIC PRICE - Designer InformationDocument3 pagesCEDRIC PRICE - Designer InformationAndrea TavaresNo ratings yet

- Stanwick 2007Document2 pagesStanwick 2007Андрій ГочNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Architecture Characteristics and ExamplesDocument10 pagesContemporary Architecture Characteristics and ExamplesTRILZ ARIS MILO ARREOLANo ratings yet

- CVDocument12 pagesCVMariam IqbalNo ratings yet

- Meta ArchitectureDocument14 pagesMeta ArchitectureRAKESH R100% (1)

- Famous Architects and Their Groundbreaking DesignsDocument28 pagesFamous Architects and Their Groundbreaking DesignsNathanniel AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Ielts Writing Task 2Document2 pagesIelts Writing Task 2Revie Victorio landeNo ratings yet

- The Reichstag Dome:: Normen FosterDocument2 pagesThe Reichstag Dome:: Normen FosterbharatiNo ratings yet

- London City Hall's sustainable design strategiesDocument6 pagesLondon City Hall's sustainable design strategiesVincent DeveraNo ratings yet

- Stately Architecture: Burntwood School in South London, Winner of The 2015 Stirling PrizeDocument6 pagesStately Architecture: Burntwood School in South London, Winner of The 2015 Stirling PrizerpmbevanNo ratings yet

- Sample Architectural Thesis ProposalDocument2 pagesSample Architectural Thesis ProposalYrral Jaime Perez67% (12)

- Bibliotheca Alexandrina and Its Architecure PDFDocument62 pagesBibliotheca Alexandrina and Its Architecure PDFegiziana_arabaNo ratings yet

- Park HillDocument3 pagesPark HillJohanna DerryNo ratings yet

- Theater Architecture ThesisDocument8 pagesTheater Architecture Thesislupitavickreypasadena100% (2)

- Piano Botin CentreDocument6 pagesPiano Botin Centreionescu_abaNo ratings yet

- Buliding Print 2472017Document16 pagesBuliding Print 2472017Dian Andriani LabiNo ratings yet

- 10 Design Principles Inspired by Iconic ArchitectureDocument9 pages10 Design Principles Inspired by Iconic ArchitectureNisrinaNurafifahNo ratings yet

- How Political Decisions Shaped London's ArchitectureDocument24 pagesHow Political Decisions Shaped London's ArchitectureLoise GakiiNo ratings yet

- Da10 PDFDocument42 pagesDa10 PDFקווין שרשרתNo ratings yet

- PreviewpdfDocument23 pagesPreviewpdfAlcoy, Alyssa Mae, A.No ratings yet

- Harbour Grace Booklet AppendicesDocument10 pagesHarbour Grace Booklet Appendicesvandana blessNo ratings yet

- Case Studies-PompiduoDocument6 pagesCase Studies-PompiduoPei JinNo ratings yet

- Rem KoolhasDocument20 pagesRem KoolhasShashank Patil100% (2)

- Nottingham Contemporary InformationDocument39 pagesNottingham Contemporary InformationJNo ratings yet

- Crow Hall 2Document9 pagesCrow Hall 2Rahma MgNo ratings yet

- Arup Journal 2 (2013)Document96 pagesArup Journal 2 (2013)Zulh HelmyNo ratings yet

- OrganizariDocument173 pagesOrganizarianne_liyNo ratings yet

- QEOP Exhibtion Brief 2Document6 pagesQEOP Exhibtion Brief 2Federico OrtizNo ratings yet

- Landmark EnglishDocument59 pagesLandmark EnglishHedi Sahdi Haji AliNo ratings yet

- Postmodern Architecture Reinterprets Form & FunctionDocument5 pagesPostmodern Architecture Reinterprets Form & FunctionNejra Uštović - PekićNo ratings yet

- The Architectural Review 201004Document40 pagesThe Architectural Review 201004Sam BatistaNo ratings yet

- Serpentine Pavilion Press PackDocument21 pagesSerpentine Pavilion Press PackAlvaro RosaDayerNo ratings yet

- Asplund BriefDocument44 pagesAsplund BriefValeria CabelloNo ratings yet

- From Paris To Chicago: The City Beautiful MovementDocument13 pagesFrom Paris To Chicago: The City Beautiful MovementJonathan Hopkins100% (1)

- The Pritzker PrizeDocument4 pagesThe Pritzker PrizeLarisa Sotelo MéndezNo ratings yet

- DiplomaWorks CaltongateDocument92 pagesDiplomaWorks CaltongateJulie LoganNo ratings yet

- Palazzo Farnese and The Habitat '67Document5 pagesPalazzo Farnese and The Habitat '67Solo GathogoNo ratings yet

- Bibliotheca Alexandrina EgyptDocument15 pagesBibliotheca Alexandrina EgyptABHISHNo ratings yet

- 04122015-2 IGS Amazing Projects in GlassDocument14 pages04122015-2 IGS Amazing Projects in GlassJuandaCabreraCoboNo ratings yet

- Architectural exhibitions as agents of changeDocument5 pagesArchitectural exhibitions as agents of changeGözde Damla TurhanNo ratings yet

- SPAB ManifestoDocument2 pagesSPAB ManifestoDaniela SilvaNo ratings yet

- Architecture,: Allied ArtsDocument59 pagesArchitecture,: Allied ArtsAj NIcoNo ratings yet

- ReichstagDocument11 pagesReichstagSaurav ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Research Design5 JKDocument35 pagesResearch Design5 JKkyleequizaNo ratings yet

- CONTEMPORARYDocument10 pagesCONTEMPORARYTRILZ ARIS MILO ARREOLANo ratings yet

- Architecture in Transition: Jacek GyurkovichDocument6 pagesArchitecture in Transition: Jacek GyurkovichShanGaviNo ratings yet

- Architectural ReviewDocument219 pagesArchitectural ReviewAnonymous LjQllp100% (2)

- Competition Conditions LRDocument104 pagesCompetition Conditions LRfcohen2366100% (1)

- History of Architecture Module IVDocument58 pagesHistory of Architecture Module IVAr Prasanth RaviNo ratings yet

- A Contemporary Archaeology of London’s Mega Events: From the Great Exhibition to London 2012From EverandA Contemporary Archaeology of London’s Mega Events: From the Great Exhibition to London 2012No ratings yet

- An Art-Lovers Guide to the Exposition Explanations of the Architecture, Sculpture and Mural Paintings, With a Guide for Study in the Art GalleryFrom EverandAn Art-Lovers Guide to the Exposition Explanations of the Architecture, Sculpture and Mural Paintings, With a Guide for Study in the Art GalleryNo ratings yet

- Hello WorldDocument1 pageHello WorldMuhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- Static Dynamic RoutingDocument4 pagesStatic Dynamic RoutingMuhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- Hello WorldDocument1 pageHello WorldMuhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- Forex TradingDocument4 pagesForex Tradingpeter1234uNo ratings yet

- List of Downloadable Files (PDF & MP3) : Webset - Level B1Document3 pagesList of Downloadable Files (PDF & MP3) : Webset - Level B1Muhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- (Artikel) Computer Forensics PDFDocument5 pages(Artikel) Computer Forensics PDFAlexander Bonaparte CruzNo ratings yet

- Nikon D700 Manual - EnglishDocument472 pagesNikon D700 Manual - EnglishRifat OzturkNo ratings yet

- Novo 7 Aurora 16gbDocument1 pageNovo 7 Aurora 16gbMuhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- SG Aspire 4740 4740G 112709Document218 pagesSG Aspire 4740 4740G 112709tryviumNo ratings yet

- HP Multiseat Computing Solution QuickspecsDocument24 pagesHP Multiseat Computing Solution QuickspecsMuhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- Ipad User Guide (iOS 6.1)Document137 pagesIpad User Guide (iOS 6.1)Binyamin GoldmanNo ratings yet

- Aquos Asia 09Document24 pagesAquos Asia 09Muhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- HP Multiseat Computing SolutionDocument3 pagesHP Multiseat Computing SolutionMuhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- Zoom User ManualDocument54 pagesZoom User ManualAl FirdausNo ratings yet

- Aspire One Service GuideDocument174 pagesAspire One Service Guidelaughinboy2860100% (1)

- 10.1371 Journal - Pone.0043827.g002Document1 page10.1371 Journal - Pone.0043827.g002Muhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- RECOMMENDED STANDARD: A Minimum of 50% of An Audit of 20 Randomly Selected Film SetsDocument1 pageRECOMMENDED STANDARD: A Minimum of 50% of An Audit of 20 Randomly Selected Film SetsMuhd Zahimi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- 201.60 - 500mm Reference OnlyDocument1 page201.60 - 500mm Reference OnlyAbdalrahem Bin Tareef TareefNo ratings yet

- Review of Julian Apostata by Richard KleinDocument7 pagesReview of Julian Apostata by Richard Kleinj.miguel593515No ratings yet

- Victor Hugo-The Last Day of A Condemned ManDocument29 pagesVictor Hugo-The Last Day of A Condemned ManIshan Marvel50% (2)

- RJA09PIVBiblographyfinalversion PDFDocument177 pagesRJA09PIVBiblographyfinalversion PDFgaurav singhNo ratings yet

- Home Theater Basics: Essential Audio & Video ComponentsDocument2 pagesHome Theater Basics: Essential Audio & Video ComponentsYazanNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Companions of The Prophet - Geographical Distribution and Political AlignmentsDocument563 pagesA Study of The Companions of The Prophet - Geographical Distribution and Political AlignmentsforkinsocketNo ratings yet

- 675 - Esl A1 Level MCQ Test With Answers Elementary Test 2Document7 pages675 - Esl A1 Level MCQ Test With Answers Elementary Test 2Christy CloeteNo ratings yet

- Volvo Wiring PDFDocument173 pagesVolvo Wiring PDFJosué Escobar100% (1)

- 3.1 Basic Trigonometry: Question PaperDocument7 pages3.1 Basic Trigonometry: Question PaperReddy GirinathNo ratings yet

- Article 9 - Visual Merchandising Window DisplayDocument7 pagesArticle 9 - Visual Merchandising Window DisplayManoranjan DashNo ratings yet

- Advocacy PamphletDocument2 pagesAdvocacy Pamphletapi-449004464No ratings yet

- New Age Old Path-Ishwar.C.Puri PDFDocument49 pagesNew Age Old Path-Ishwar.C.Puri PDFDaniel David AzocarNo ratings yet

- L-O-V-E: Alto SaxDocument9 pagesL-O-V-E: Alto SaxBenjamin PalmonNo ratings yet

- Rahat Ul Ashiqeen Ver 12Document20 pagesRahat Ul Ashiqeen Ver 12Idara Rahat Ul AshiqeenNo ratings yet

- Huawei Sne Mobile Phone User Guide - (Emui9.0.1 - 01, En-Uk, Normal)Document68 pagesHuawei Sne Mobile Phone User Guide - (Emui9.0.1 - 01, En-Uk, Normal)FarzadNo ratings yet

- Lauren Guiteras ResumeDocument1 pageLauren Guiteras ResumeLauren GuiterasNo ratings yet

- Cardinal Direction: Earth Magnetic CompassDocument1 pageCardinal Direction: Earth Magnetic CompassTeodor NastevNo ratings yet

- Sri Satyanarayana Pooja Samagri ListDocument2 pagesSri Satyanarayana Pooja Samagri ListVenkat NukarajuNo ratings yet

- List of Radio StationsDocument13 pagesList of Radio StationsNishi Kant ThakurNo ratings yet

- Pastoral Role in Equipping The Church'S Involvement in God'S MissionDocument7 pagesPastoral Role in Equipping The Church'S Involvement in God'S MissionDr PothanaNo ratings yet

- Medieval Education Systems: Monasticism, Scholasticism & ChivalryDocument63 pagesMedieval Education Systems: Monasticism, Scholasticism & ChivalryKaren Joy OrtizNo ratings yet

- Test Grilă La Limba Engleză - Profilul Subofiţeri - Filiera Indirectă Varianta Nr.1 Partea I: CITITDocument9 pagesTest Grilă La Limba Engleză - Profilul Subofiţeri - Filiera Indirectă Varianta Nr.1 Partea I: CITITAndreea GrecuNo ratings yet

- Bruch - Kol Nidrei PDFDocument13 pagesBruch - Kol Nidrei PDFManuel MazaNo ratings yet

- Solid Edge ShortcutsDocument3 pagesSolid Edge Shortcutsabekkernens100% (1)

- Thousand Years Lyrics by Christina PerriDocument1 pageThousand Years Lyrics by Christina PerrianggandakonohNo ratings yet

- TwistAPlot 01 - The Time Raider - R L Stine (siPDF)Document100 pagesTwistAPlot 01 - The Time Raider - R L Stine (siPDF)Zorrro0% (1)

- Lawang SewuDocument4 pagesLawang SewuDjoko WidodoNo ratings yet

- Indian Ethos in Management-The BibleDocument12 pagesIndian Ethos in Management-The Biblenoor_fatima04No ratings yet

- Succeed in Cambridge Pet 10 Practice tests-KEYS PDFDocument2 pagesSucceed in Cambridge Pet 10 Practice tests-KEYS PDFTienNguyen50% (6)

- Coating Equivalent List KCCDocument3 pagesCoating Equivalent List KCCchrismas_g100% (2)