Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Semantic Classifications of The Verb

Uploaded by

Carmen Maria FluturaşOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Semantic Classifications of The Verb

Uploaded by

Carmen Maria FluturaşCopyright:

Available Formats

Semantic classifications of the verb 0

: Miracleworld | : | : 13-06-2011

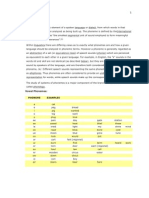

Semantic classifications of the verb may be undertaken from different standpoints. Grammatically important is the devision of verbs into the following classes: Actional verbs, which denote actions proper (do, make, go, read, etc.) and statal verbs, which denote state (be, exist, lie, sit, know, etc.) or relations (fit, belong, have, match, cost, etc.). The difference in their categorical meaning affects their morphological paradigm: statal and relational verbs have no passive voice (though some have forms coinciding with the passive voice as in The curtainsand the carpet were matched ). Also statal and relational verbs generally are not used in the continuous and perfect continuous tenses. Their occasional use in these tenses is always exceptional and results in the change of meaning. From the syntactic standpoint verbs may be subdivided into transivite () andintransitive () ones. Without the object the meaning of the transitive verb is incomplete or entirely different. Transitive verbs may be followed: a) by one direct object (monotransitive verbs); Jane is helping her sister. b) by a direct and an indirect objects (ditransitive verbs); Jane gave her sister an apple. c) by a prepositional object (prepositional transitive verbs): Jane looks after her sister. Intransitive verbs do not require any object for the completion of their meaning: The sun is rising. There are many verbs in English that can function as both transitive and intransitive. Tom is writing a letter. (transitive) Tom writes clearly. (intransitive) Who has broken the cup? (transitive) Glass breaks easily. (intransitive) Jane stood near the piano. (intransitive) Jane stood the vase on the piano. (transitive) The division of verbs into terminative and non-terminative depends on the aspectual characteristic in the lexical meaning of the verb which influences the use of aspect forms. Terminative verbs ( ) besides their specific meaning contain the idea that the action must be fulfilled and come to an end, reaching

some point where it has logically to stop. These are such verbs as sit down, come, fall, stop, begin, open, close, shut, die, bring, find, etc. Non-terminative, or durative verbs( ) imply that actions or states expressed by these verbs may go on indefinitely without reaching any logically necessary final point. These are such verbs as carry, run, walk, sleep, stand, sit, live, know, suppose, talk, speak, etc. The end, which is simply an interruption of these actions, may be shown only by means of some adverbial modifier: He slept till nine in the morning. The last subclass comprises verbs that can function as both terminative and non-terminative (verbs of double aspectual meaning). The difference is clear from the context: Can you see well? (non-terminative) I see nothing there. (terminative)

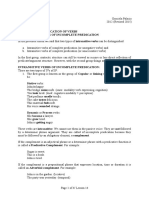

Construction of verb semantic classes Verb semantic classes are then constructed from verbs, modulo exceptions, which undergo a certain number of alternations. From this classification, a set of verb semantic classes is organized. We have, for example, the classes of verbs of putting, which include Put verbs, Funnel Verbs, Verbs of putting in a specified direction, Pour verbs, Coil verbs, etc. Other sets of classes include Verbs of removing, Verbs of Carrying and Sending, Verbs of Throwing, Hold and Keep verbs, Verbs of contact by impact, Image creation verbs, Verbs of creation and transformation, Verbs with predicative complements, Verbs of perception, Verbs of desire, Verbs of communication, Verbs of social interaction, etc. As can be noticed, these classes only partially overlap with the classification adopted in WordNet. This is not surprising since the classification criteria are very different. Let us now look in more depth at a few classes and somewhat evaluate the use of such classes for natural language applications (note that several research projects make an intensive use of B. Levin's classes). Note that, w.r.t. WordNet, the classes obtained via alternations are much less hierarchically structured, which shows that the two approaches are really orthogonal.

There are other aspects which may weaken the practical use of this approach, in spite of its obvious high linguistic interest, from both theoretical and practical viewpoints. The first point is that the semantic definition of some classes is somewhat fuzzy and does not really summarize the semantics of the verbs it contains. An alternative would be to characterize a class by a set of features, shared to various extents by the verbs it is composed of. Next, w.r.t. the semantic characterization of the class, there are some verbs which seem to be really outside the class. Also, as illustrated below, a set of classes (such as movement verbs) does not include all the `natural' classes one may expect (but `completeness' or exhaustiveness has never been claimed to be one of the objectives of this research). This may explain the unexpected presence of some verbs in a class. Finally, distinctions between classes are sometimes hard to make, and this is reinforced by the fact that classes may unexpectedly have several verbs in common. Let us illustrate these observations with respect to two very representative sets of classes: verbs of motion and verbs of transfer of possession (notice that a few other classes of transfer of possession, e.g. deprivation, are in the set of classes of Remove verbs).

You might also like

- Applied Cognitive Construction Grammar: Understanding Paper-Based Data-Driven Learning Tasks: Applications of Cognitive Construction Grammar, #1From EverandApplied Cognitive Construction Grammar: Understanding Paper-Based Data-Driven Learning Tasks: Applications of Cognitive Construction Grammar, #1No ratings yet

- Applied Cognitive Construction Grammar: A Cognitive Guide to the Teaching of Phrasal Verbs: Applications of Cognitive Construction Grammar, #3From EverandApplied Cognitive Construction Grammar: A Cognitive Guide to the Teaching of Phrasal Verbs: Applications of Cognitive Construction Grammar, #3No ratings yet

- A method of linguistic analysisDocument6 pagesA method of linguistic analysisNiken SoenaryoNo ratings yet

- Grammar GuideDocument8 pagesGrammar GuideIvánNo ratings yet

- Inflectional MorphologyDocument37 pagesInflectional MorphologyFriadmo SaragihNo ratings yet

- 2 Sentence, Utterance, PropositionDocument3 pages2 Sentence, Utterance, PropositionsofiaNo ratings yet

- Unit 36 MultiDocument6 pagesUnit 36 Multij pcNo ratings yet

- The Preposition The PrepositionDocument9 pagesThe Preposition The PrepositionЭльвира МатыгулинаNo ratings yet

- Inglese 2Document28 pagesInglese 2Roberta GambinoNo ratings yet

- Lexical and Grammatical categories in English explainedDocument3 pagesLexical and Grammatical categories in English explainedSteve HaringgtonNo ratings yet

- A linguistic analysis checklistDocument4 pagesA linguistic analysis checklistVioleta Nacheva100% (2)

- Lecture 3Document11 pagesLecture 3ZKushakovaNo ratings yet

- LMA An. I-Sem 1-Engleza LEC-The Category of Aspect & Aspect 2-Reedited OnDocument10 pagesLMA An. I-Sem 1-Engleza LEC-The Category of Aspect & Aspect 2-Reedited OnCrina MiriamNo ratings yet

- Baba BumDocument14 pagesBaba BumMarkoNo ratings yet

- L&s ChecklistDocument3 pagesL&s ChecklistzeldavidNo ratings yet

- lecture 3Document16 pageslecture 3kundyz083No ratings yet

- перелік питань на залік - 20 - 21Document13 pagesперелік питань на залік - 20 - 21Переяслав ПереяславNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3. The Theory of Grammatical Classes of Words. Classes of WordsDocument10 pagesLecture 3. The Theory of Grammatical Classes of Words. Classes of WordsДенис МитрохінNo ratings yet

- How Language Works - CHAPTER7 - 140110Document33 pagesHow Language Works - CHAPTER7 - 140110minoasNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Parts of The SentDocument3 pagesCriteria For Parts of The SentЮлия ПолетаеваNo ratings yet

- Grammar II Introduction GralrevisionDocument3 pagesGrammar II Introduction GralrevisionAbigail LandaNo ratings yet

- Syntax-1 (1) - 2Document11 pagesSyntax-1 (1) - 2Àbdęrrāhîm Baț Øű ŁíNo ratings yet

- The Verb as a Lexical Class: Forms and FunctionsDocument13 pagesThe Verb as a Lexical Class: Forms and FunctionsStark UnicornNo ratings yet

- Parts of Speech Classification ProblemDocument6 pagesParts of Speech Classification ProblemАяжвн СыдыковаNo ratings yet

- Teaching Grammar Form Meaning and UseDocument6 pagesTeaching Grammar Form Meaning and UseKimberley Sicat Bautista0% (1)

- English Morphology and Syntax 1 Some Essential ConceptsDocument7 pagesEnglish Morphology and Syntax 1 Some Essential ConceptsAlicia DomínguezNo ratings yet

- Syntax1 PDFDocument7 pagesSyntax1 PDFfarhanNo ratings yet

- LST 313 Class Notes 1Document15 pagesLST 313 Class Notes 1Ebinabo EriakumaNo ratings yet

- Eng 3110 (English Language Studies 4)Document4 pagesEng 3110 (English Language Studies 4)δαι δαιNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2.2. Part-Of-Speech TheoriesDocument15 pagesLecture 2.2. Part-Of-Speech TheoriesGulziya MaratkyzyNo ratings yet

- Understanding Grammatical Names and FunctionsFrom EverandUnderstanding Grammatical Names and FunctionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Structure of English LanguageDocument26 pagesThe Structure of English Languagekush vermaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Syntax LinguisticsDocument4 pagesMorphology and Syntax LinguisticsCélia ZENNOUCHENo ratings yet

- Morphological ProcessesDocument19 pagesMorphological ProcessesLuqman HakimNo ratings yet

- Understanding Lexemes and Their RelationshipsDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Lexemes and Their RelationshipsSoviatur rokhmaniaNo ratings yet

- Grammar Form Meaning and UseDocument8 pagesGrammar Form Meaning and UseShy PaguiganNo ratings yet

- GRAMMATICAL CLASSES OF VERBSDocument12 pagesGRAMMATICAL CLASSES OF VERBSEliza SaidalievaNo ratings yet

- Vowel Phonemes: Phoneme ExamplesDocument6 pagesVowel Phonemes: Phoneme ExamplesAnna Rhea BurerosNo ratings yet

- POS Tagging 2.0Document14 pagesPOS Tagging 2.0Saif Ur RahmanNo ratings yet

- MORPHOLOGYDocument6 pagesMORPHOLOGYErika BonillaNo ratings yet

- The Structure of English LanguageDocument35 pagesThe Structure of English LanguageAlexandre Alieem100% (3)

- Morphology, Syntax and SemanticsDocument4 pagesMorphology, Syntax and SemanticspushpNo ratings yet

- Grammar Form Meaning and UsesDocument8 pagesGrammar Form Meaning and UsesShy PaguiganNo ratings yet

- 16 FUNCTIONAL PARTS OF SPEECHDocument4 pages16 FUNCTIONAL PARTS OF SPEECHLesia ZalistovskaNo ratings yet

- A Course of Modern English Lexicology: Final Examination QuestionsDocument16 pagesA Course of Modern English Lexicology: Final Examination QuestionsAnna IspiryanNo ratings yet

- Tense Aspect Modality Course OverviewDocument11 pagesTense Aspect Modality Course OverviewGabriel CosteaNo ratings yet

- MORPHOLOGY SYNTAX SEMANTICS ReviewerDocument13 pagesMORPHOLOGY SYNTAX SEMANTICS ReviewerMarissa EsguerraNo ratings yet

- The Verb LectureDocument20 pagesThe Verb LectureDashaNo ratings yet

- Unit 31 The VerbDocument16 pagesUnit 31 The Verbj pcNo ratings yet

- Lesson 8. Lexical Categories Introduction DiscussionDocument6 pagesLesson 8. Lexical Categories Introduction DiscussionColleen CastueraNo ratings yet

- Formal and Functional GrammarDocument4 pagesFormal and Functional Grammarnino tsurtsumiaNo ratings yet

- Parts of SpeechDocument8 pagesParts of SpeechPilar AuserónNo ratings yet

- Syntax Introduction To LinguisticDocument6 pagesSyntax Introduction To LinguisticShane Mendoza BSED ENGLISHNo ratings yet

- The Noun Its Grammatical CategoriesDocument4 pagesThe Noun Its Grammatical CategoriestemurlankuziboevNo ratings yet

- 4 Seminar. TCALDocument24 pages4 Seminar. TCALBohdana MysanetsNo ratings yet

- Skripta 2013Document47 pagesSkripta 2013Ćipći RipćiNo ratings yet

- Gramatica Engleza - Morfologie LECDocument44 pagesGramatica Engleza - Morfologie LECSabiutza TomaNo ratings yet

- 01.curs Introductiv MorfoDocument5 pages01.curs Introductiv MorfoVlad SavaNo ratings yet

- Preface AbdoDocument34 pagesPreface AbdoAbdelhadi Ait AllalNo ratings yet

- Choose The Correct Answer Fun Activities Games Games - 26152Document2 pagesChoose The Correct Answer Fun Activities Games Games - 26152Carmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Circle The Correct Word For The Sentence. What Does The Other Word Mean?Document3 pagesCircle The Correct Word For The Sentence. What Does The Other Word Mean?Carmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- My Future Job Planification CalendaristicaDocument9 pagesMy Future Job Planification CalendaristicaCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Past simple verb fill in sentences ESL activityDocument2 pagesPast simple verb fill in sentences ESL activityAdhi WidyariNo ratings yet

- Past simple verb fill in sentences ESL activityDocument2 pagesPast simple verb fill in sentences ESL activityAdhi WidyariNo ratings yet

- 1Document1 page1Carmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Starter Module Module 1-Free Time Unit 1a. Free-Time Activities Unit 1b. Character AdjectivesDocument6 pagesStarter Module Module 1-Free Time Unit 1a. Free-Time Activities Unit 1b. Character AdjectivesNicolle IonescoNo ratings yet

- Stronger (What Doesn't Kill You) : Kelly ClarksonDocument2 pagesStronger (What Doesn't Kill You) : Kelly ClarksonCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Planificare Anuala Click On 3 Clasa A 9a L2Document10 pagesPlanificare Anuala Click On 3 Clasa A 9a L2Carmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Unjumble sentences and questionsDocument1 pageUnjumble sentences and questionsVuksanovic MilijanaNo ratings yet

- Planificare Anuala Click On 3 Clasa A 9a L2Document10 pagesPlanificare Anuala Click On 3 Clasa A 9a L2Carmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Starter Module Module 1-Free Time Unit 1a. Free-Time Activities Unit 1b. Character AdjectivesDocument6 pagesStarter Module Module 1-Free Time Unit 1a. Free-Time Activities Unit 1b. Character AdjectivesNicolle IonescoNo ratings yet

- Conrad - TextDocument1 pageConrad - TextCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Holidays, A Song ("Brighton in The Rain") and The Good Ol' Present Perfect!Document3 pagesHolidays, A Song ("Brighton in The Rain") and The Good Ol' Present Perfect!Carmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Sunday Times, Mentally Filing Away Information About The Latest Books, Plays, Films, andDocument2 pagesSunday Times, Mentally Filing Away Information About The Latest Books, Plays, Films, andAnimalute HaioaseNo ratings yet

- English ST: "Tess Durbeyfield at This Time of Her Life Was A Mere Vessel of Emotion Untinctured by Experience"Document1 pageEnglish ST: "Tess Durbeyfield at This Time of Her Life Was A Mere Vessel of Emotion Untinctured by Experience"Animalute HaioaseNo ratings yet

- Fitzgerald's Short Story About a Man Who Ages in ReverseDocument2 pagesFitzgerald's Short Story About a Man Who Ages in ReverseCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Prepositional and Verb PhrasesDocument6 pagesPrepositional and Verb PhrasesAnimalute HaioaseNo ratings yet

- The Curious Case of Benjamin Button EseuDocument2 pagesThe Curious Case of Benjamin Button EseuCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Lolita Writing StyleDocument8 pagesLolita Writing StyleCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- PraislerDocument8 pagesPraislerCarmen Maria Fluturaş100% (1)

- Exam QuestionsDocument2 pagesExam QuestionsCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- PV TheoryDocument5 pagesPV TheoryCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Textul de Mai Sus Este deDocument1 pageTextul de Mai Sus Este deCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Staff Duties Qualifications Interview GuideDocument10 pagesStaff Duties Qualifications Interview GuideCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Polysemy and HomonymyDocument76 pagesPolysemy and HomonymyCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Appendix 1Document5 pagesAppendix 1Carmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Similes, Proverbs, EtcDocument4 pagesSimiles, Proverbs, EtcCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Phrasal VerbsDocument8 pagesPhrasal VerbsCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Past Tense ExercisesDocument2 pagesPast Tense ExercisesCarmen Maria FluturaşNo ratings yet

- Active and PassiveDocument9 pagesActive and PassiveDivya Rai SharmaNo ratings yet

- Basic Sentence PatternsDocument35 pagesBasic Sentence PatternsSarah Shahnaz Ilma100% (2)

- Active and Passive VoiceDocument73 pagesActive and Passive Voicevkm_ctrNo ratings yet

- Phrasal Verbs: What Is A Phrasal Verb?Document3 pagesPhrasal Verbs: What Is A Phrasal Verb?BondfriendsNo ratings yet

- Grammar Examination Week 2Document4 pagesGrammar Examination Week 2Inshan MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Ergative Verbs 1Document6 pagesErgative Verbs 1Altar IstnNo ratings yet

- Eng Module Week 1Document19 pagesEng Module Week 1Tyrone Dave BalitaNo ratings yet

- Discourse and Function - Pick PDFDocument418 pagesDiscourse and Function - Pick PDFSalim Al-khammashNo ratings yet

- Test Ingl..Document13 pagesTest Ingl..Ronald Amaya GaonaNo ratings yet

- Tema 22Document9 pagesTema 22Leti CiaNo ratings yet

- Lectures of 1, 2, 3, 4 Weeks Prepared By: Assist. Lecturer Jwan Ahmed MustafaDocument24 pagesLectures of 1, 2, 3, 4 Weeks Prepared By: Assist. Lecturer Jwan Ahmed MustafaShwan T HarkiNo ratings yet

- Parts of Speech VerbsDocument30 pagesParts of Speech VerbsImam YudhoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 14 Syntactic Classification of Verbs Intransitive Verbs of Incomplete PredicationDocument4 pagesLesson 14 Syntactic Classification of Verbs Intransitive Verbs of Incomplete PredicationLaydy HanccoNo ratings yet

- CLASSIFICATION OF VERBS - Hoja 1-2Document2 pagesCLASSIFICATION OF VERBS - Hoja 1-2Maru C.No ratings yet

- Latin Direct Obj 2Document2 pagesLatin Direct Obj 2Magister Cummings75% (4)

- Surigaonon Grammar PDFDocument38 pagesSurigaonon Grammar PDFcristine maeNo ratings yet

- 88 Phrasal-Verbs US StudentDocument27 pages88 Phrasal-Verbs US StudentXimena Maria Rivera SolisNo ratings yet

- Preminger Ergativity and Basque Unergatives HandoutDocument13 pagesPreminger Ergativity and Basque Unergatives HandoutdharmavidNo ratings yet

- Transitive and Intransitive VerbsDocument11 pagesTransitive and Intransitive VerbsVengat BalaNo ratings yet

- SENTENCE PATTERN PronounDocument6 pagesSENTENCE PATTERN PronounDhittaNo ratings yet

- English Grammar 4: University OF Basrah College OF Education FOR Human Sciences Department OF EnglishDocument37 pagesEnglish Grammar 4: University OF Basrah College OF Education FOR Human Sciences Department OF EnglishNaseer الغريريNo ratings yet

- 01-Lecture-Functional EnglishDocument14 pages01-Lecture-Functional Englishapi-648327758No ratings yet

- UUEG03 TG App pp227 242Document16 pagesUUEG03 TG App pp227 242Lutfia MinhoneyNo ratings yet

- Verbs: Types, Examples, and ExercisesDocument15 pagesVerbs: Types, Examples, and ExercisesJuwita PardedeNo ratings yet

- Culegere 2011Document55 pagesCulegere 2011Carmen SimionovNo ratings yet

- My MonographDocument19 pagesMy MonographAiman100% (1)

- B. Sentence and Its ElementsDocument13 pagesB. Sentence and Its ElementsHermansyah flamboyanNo ratings yet

- Finite VerbDocument9 pagesFinite VerbfaranimohamedNo ratings yet

- Mamgrammarinoutl00englrich PDFDocument272 pagesMamgrammarinoutl00englrich PDFOcsicnarfX100% (1)

- Daily Lesson Plan 4 Verb PhrasesDocument2 pagesDaily Lesson Plan 4 Verb PhrasesJacqueline Skylar75% (4)