Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Taxation Project - Aalim Khan, Roll No. 505, 7th Semester

Uploaded by

Ashish GillOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Taxation Project - Aalim Khan, Roll No. 505, 7th Semester

Uploaded by

Ashish GillCopyright:

Available Formats

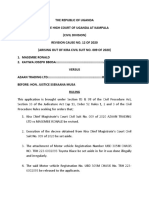

Escotal Mobile Communications Ltd. vs. Union of India and ors. (Kerala H.C.) Citation- 2006 [2] S.T.R.

567. Quorum- (2 Judges) - B.N. Srikrishna, C.J., M. Ramachandran, J. Facts of the caseThe petitioner in the instant case was engaged in cellular telephone business within Kerala and also provided other services like selling cellular telephone instruments, SIM cards and other accessories. It purchased these accessories from States outside Kerala by paying Central sales tax. For selling the products within the State of Kerala, it paid sales tax under the Kerala General Sales Tax (KGST) Act, 1963. According to the petitioner, the sale of the instrument and the SIM card to its customers was only a sale pure and simple liable only to sales tax under the KGST Act. The petitioner also rendered activation services on which it paid service tax (activation is a process by which the details of the customer are manually fed into computer to provide a database which can provide access for the customer to use the net work). It was the stand of the petitioner that activation neither increases nor decreases the value of SIM card, since it was not a process carried out on the SIM card, but only on the computer in the petitioners office. The petitioner was duly paying the sales tax for sales of SIM cards and service tax on the activation charges. However, the respondent subsequently asked the petitioner to show cause as to why the value of SIM cards was not to be included in the taxable service for the purpose of computing service tax. The petitioner, in his reply, made a distinction between sale of the SIM card for which it charged consideration, and the activation charges which according to it was not a sale, but a mere service. The petitioner pointed out that, as far as the sale part was concerned, it was paying sales tax and was also paying service tax on activation charges. Finally, by an order made after one month; the respondent demanded service tax payable on the value of SIM cards and also imposed penalties upon the petitioner under various provisions of the Finance Act, 1984.

JudgmentThe Kerala High Court held that: The transaction of sale of SIM card was liable to sales tax under the KGST Act. The activation charges paid were also liable to sales tax under the same Act. The selling of the SIM card and the process of activation are services provided to the customer and fall within the definition of taxable service as defined in s. 65(72)(b) of the Finance Act. They are also liable to service tax under the Finance Act.

Case AnalysisThere were four main contentions which arose from the facts mentioned above: (a). Whether the supply of SIM cards is sale as defined under KGST Act? (b). If yes; whether the activation charges are a part of sale as defined under KGST Act and thus liable to sales tax? (c). Can the combined value of sale of SIM and activation charges be taxed under both sales tax and service tax? (d). Is the sale of SIM cards taxable service under s.65 (72) (b) of the Finance Act? (a). The petitioner disputed all elements of definition of sale under s. 2(xxi) r.w. Explanation 3B of the KGST Act. It argued that firstly; in order to fall within the meaning of the word sale as defined in Section 2(xxi), there has to be a transfer of the property in the goods for cash or other valuable consideration. A SIM card by itself has no value. It is only a key to enter the service provider's facility and use his services. It is only after activation that it has some value. Since activation is a service; the petitioners are only chargeable to service tax for activation charges and not sales tax either for activation or for the SIM under KGST Act. The petitioner relied upon PSI Data Systems Ltd vs. Collector of Central Excise in which the Supreme Court held that a computer may not be capable of effective functioning unless loaded with software such as discs, floppies etc. but that does not mean that these are a part of the computer for the purpose of taxation. Their value does not form part of the taxable value of the computer for the purposes of excise duty. The petitioner tried to link this with the facts of the present case and asserted that even though a handset will not work without a SIM; even after it is added; the handset is useless unless it is activated. The insertion of a SIM card does act as value addition to the taxable

amount and it is only after activation that value of the handset increases. Thus, it is only logical that only the amount of activation should be assessed to tax. The respondent, on the other hand; argued that sales tax under KGST Act is to be levied on both sales of SIM and activation charges. It proved that the definition of sale has become wider in scope by insertion of explanation 3B to KGST Act in 1984. Thus, tax on sale or purchase of goods now also includes a transfer of right to use any goods for any purpose for any valuable consideration. So even if SIM card has itself no value (as the petitioner argued); it definitely represents a transfer of right to use the service of the cellular telephone service provider for a specified period upon payment of valuable consideration. Hence, the sale of SIM card will also be taxable as tax on sale of goods under s. 2(xxi) r.w. exp. 3B of the KGST Act. The petitioner tried to refute the above argument by contesting that even if it is accepted that the there is a transfer of right to use the SIM card to the customers; SIM card is not goods as defined under the said section. This was because according to him; (as in Associated Cements case) whenever an intangible benefit passes to the customer, it can never amount to anything other than service and thus liable only to service tax. In order to amount to sale under the KGST Act, what is transferred must be a tangible benefit in a movable property. And in the present case, there was nothing tangible transferred to the customers but only a right to use service (which was intangible property). Thus, if they are not goods; the right to use them (as urged by the respondent) would also not come under the purview of goods; as s. 2(xii) of the KGST Act would not apply to intangible property. The petitioner was however; was not able to prove that sale of a copy right or a patent right, though sale of intangible property would not attract sales tax (as in Vikas Sales Corporation v. Commissioner of Commercial Taxes; in which it was held by apex court that even an intangible property, i.e. the right to use transfer of REP licenses for valuable consideration amounted to sale under different State Sales Tax Acts). This would mean that even the transfer of an intangible right in a movable property also came under the purview of sale as defined under the KGST Act.

The last contention of the petitioner in this regard was that the usage services by the customer of mobile phone was through wireless techniques, made possible through instruments placed in their office which were immovable property. But to qualify as sale under the KGST Act, there had to be a transfer of right to use movable property. The court rejected this argument since no material was placed before it to decide this matter and left it open to the statutory authorities to decide whether those equipments installed in petitioners office were movable or immovable property based upon available evidence. In the absence of any evidence to that effect at that instant; it proceeded on the assumption that the instruments were movable property. Hence, with regard to the first contention; it was held that the transaction of sale of SIM card is without doubt liable to sales tax under the KGST Act. (b). The petitioner urged that firstly, there was sale and purchase of SIM card, on which sales tax could be legitimately imposed and then there was activation on which service tax could be legitimately imposed. In other words, both were exclusive and separate transactions liable to two different types of tax. Thus, the sale of SIM card was not liable to service tax; nor was the service provided by activation liable to sales tax. The respondent, on the other hand, correctly submitted that what was styled as activation charges were nothing but deferred consideration for the same sale. The transaction of the sale of SIM and activating it was a single transaction done in two steps. Firstly, there was transfer of SIM card on payment of certain charges; secondly, by the process of activation on payment of activation charges. In other words, it was a continuous process of sale, as it was a transfer of the right to use the facility of the mobile service provider in two steps, the consideration being paid in three installments and the transaction being a single transaction. (c). Thirdly, the petitioner contented that the sale of SIM cards was not a taxable service under s. 65(72)(b) of the Finance Act because it was measured by relating it to the value of taxable sale. The court, however, held that the petitioner was at error in not concentrating upon the taxable event. Merely because a tax was measured by relating it to the value of taxable sale, it did not cease to be a service tax, because the taxable event was the rendering of service and not the sale.

(d). The last contention of the petitioner was that the acceptance of the argument of the respondent would result in taxation of the same transaction under both sales tax and service tax; which would be impermissible since it would be impossible that the same transaction can be treated both as sale and as service. If that were to be done, then the legislation would be bad in law as it would result in double taxation. In reality, however, what was presented by the petitioner as two mutually exclusive transactions was a single transaction having two stages; each of which contained two aspects of sale and service. This theory, (known as theory of aspect legislation) the court held; was not new to taxing statutes and it was perfectly lawful to tax two or more aspects of the same transaction under different categories of tax. This would mean that different legislatures can impose tax on particular aspects of the same transaction. The justification for this theory is that subjects which in one aspect and for one purpose fall within the power of a particular Legislature may in another aspect and for another purpose fall within another legislative power. For example, in case of the annual letting value of a property in the occupation of a person for his own residence; one aspect is the levy of property tax under State law and another aspect is levy of Income Tax under Income Tax Act (by the Parliament). This is irrespective of the fact that the law with respect to a subject might incidentally affect another subject in some way. The same transaction may involve two or more taxable events in its different aspects. This is precisely what was done in the instant case since there was no separate transaction of sale and separate transaction of service. There was a single transaction (giving mobile connection to the consumer) completed in two stages or parts (sale of SIM and activation) and each of these stages had two aspects to them for the purpose of taxation (sale and service). The sale of SIM cards and activation were two stages to a single transaction and not mutually unconnected ones. In other words, they were to be taxed as a single transaction and not distinctly as taxation on sale of SIM and taxation on activation charges. It was a composite transaction made up of two correlated taxable events. The taxable event for sales tax was obviously the sale as understood in Section 2(xxi) under the KGST Act and the taxable event for levy of service tax was also taxable service under s. 65(72)(b) of the Finance Act. But the effect of this decision was that sale under state Act meant both sale of SIM and service of activation and taxable service under the

central legislation also included both. This was justified because ultimately both were part of a single transaction and taxed by state and union for different purposes. Another related fear expressed by the petitioner was that to tax the same transaction as both sales and services would amount to double taxation. The petitioner while mentioning this argument, however, overlooked the underlying principle of double taxation. Nothing can be termed as double taxation if it is not levied by the same authority or imposed for the same purpose. In the present case, while the State Legislature was competent to impose tax on sale by a legislation relatable to entry 54 of List II of Seventh Schedule, the tax on the aspect of services rendered not being relatable to any entry in the State List; came within the legislative competence of Parliament under Article 248 r.w. entry 97 of List I of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution. Thus, sales tax and service tax came under competence of different authorities, i.e. state legislature and Parliament respectively. So there was no question of double taxation. Once the aspect theory is kept in focus, it would be clear that the same transaction was liable to different taxes in its different aspects. Thus, the gist of the matter is that the pith and substance of the transaction is to be seen. Sales tax is different from service tax and same transaction may involve service and sales as its two aspects and it is not impermissible or illegal for two different legislatures to tax such aspects which fall within their individual competence. Seen in the light of the present facts, it was held that for the purpose of sales tax, sale of SIM cards was eligible for sales tax and service tax also (because the insertion of SIM card and its subsequent activation were two events linked together as a part of same transaction of providing the service of wireless communication to the consumer) and both events were complementary. Similarly, the process of activation was also liable to service tax under the Finance Act as well as sales tax under the state (KGST) Act.

You might also like

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Tax DigestDocument6 pagesTax DigestjoyfandialanNo ratings yet

- Si04253409 4 PDFDocument1 pageSi04253409 4 PDFclintNo ratings yet

- Criminal Appeal Drafting Criminal TemplateDocument7 pagesCriminal Appeal Drafting Criminal TemplateAshish Gill67% (3)

- Taxation Digest on VAT LiabilityDocument27 pagesTaxation Digest on VAT LiabilityBer Sib JosNo ratings yet

- Consumer Protection in India: A brief Guide on the Subject along with the Specimen form of a ComplaintFrom EverandConsumer Protection in India: A brief Guide on the Subject along with the Specimen form of a ComplaintNo ratings yet

- Gujarati BaraksadiDocument2 pagesGujarati Baraksadijigi7768% (28)

- Tax DigestDocument18 pagesTax DigestMhayBinuyaJuanzonNo ratings yet

- Taxation Q&ADocument18 pagesTaxation Q&AZsazsaNo ratings yet

- Very Important Judgements - All ActsDocument19 pagesVery Important Judgements - All ActsKumar Naveen0% (1)

- Cases For VAT (Digest)Document371 pagesCases For VAT (Digest)Hazel Reyes-AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Landmark VAT Cases on Zero-Rated Sales and Franchise OperationsDocument12 pagesLandmark VAT Cases on Zero-Rated Sales and Franchise OperationsJudeRamosNo ratings yet

- AT&T Philippines v CIR VAT refund denied due to invoice submissionDocument2 pagesAT&T Philippines v CIR VAT refund denied due to invoice submissionSSNo ratings yet

- Taxation Law Review Cases Digest IIDocument34 pagesTaxation Law Review Cases Digest IIJohney DoeNo ratings yet

- Linberg V MakatiDocument2 pagesLinberg V MakatiChimney sweepNo ratings yet

- Acct Statement - XX9566 - 04012023Document4 pagesAcct Statement - XX9566 - 04012023ANKIT SINGHNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship Project Report ON "Itr E-Filing": Subject Code:KMBN308Document60 pagesSummer Internship Project Report ON "Itr E-Filing": Subject Code:KMBN308Sumit Ranjan100% (6)

- Maritime Law SyllabusDocument1 pageMaritime Law SyllabusAshish Gill100% (1)

- Maritime Law SyllabusDocument1 pageMaritime Law SyllabusAshish Gill100% (1)

- Taxpayer's Remedies - Drilon vs. Lim GR No. 111249, August 4, 1994Document3 pagesTaxpayer's Remedies - Drilon vs. Lim GR No. 111249, August 4, 1994Jade Palace TribezNo ratings yet

- CREBA v. Exec. Sec. Romulo, March 9, 2010Document2 pagesCREBA v. Exec. Sec. Romulo, March 9, 2010NERNANIE FRONDA100% (1)

- Monese Statement 01 May 2023 - 23 August 2023Document12 pagesMonese Statement 01 May 2023 - 23 August 2023Andrea SarocoNo ratings yet

- VAT on Toll Fees CaseDocument7 pagesVAT on Toll Fees Casechappy_leigh118No ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument11 pages1 PDFVIJAYKUMARNo ratings yet

- International Maritime ConventionsDocument30 pagesInternational Maritime ConventionsAshish Gill83% (6)

- NIPPON EXPRESS (PHILIPPINES) CORPORATION v. CIRDocument3 pagesNIPPON EXPRESS (PHILIPPINES) CORPORATION v. CIRlucky50% (2)

- Tax ProjectDocument7 pagesTax Projectipant2884No ratings yet

- BSNL v. Union of IndiaDocument10 pagesBSNL v. Union of IndiaMayank Jain100% (4)

- Cir vs. Isabela Cultural Corporation (Icc) : Issue/SDocument5 pagesCir vs. Isabela Cultural Corporation (Icc) : Issue/SMary AnneNo ratings yet

- 2013 3 227 TridelDocument5 pages2013 3 227 TridelDipesh Chandra BaruaNo ratings yet

- In The Customs Excise & Service Tax Appellate Tribunal West Block No.2, R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066Document10 pagesIn The Customs Excise & Service Tax Appellate Tribunal West Block No.2, R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066Dipesh Chandra BaruaNo ratings yet

- 52 Recent Judgements STDocument131 pages52 Recent Judgements STvudatalj123No ratings yet

- Lally Automobiles DelHCDocument12 pagesLally Automobiles DelHCShivinder SinglaNo ratings yet

- CP 2501 of 2019 Jain Sales Vs MSWIPE TECHNOLOGIES PVT LTDDocument9 pagesCP 2501 of 2019 Jain Sales Vs MSWIPE TECHNOLOGIES PVT LTDAshhab KhanNo ratings yet

- CREBA, INC. VS. EXEC. SECRETARYDocument8 pagesCREBA, INC. VS. EXEC. SECRETARYVan John MagallanesNo ratings yet

- Cta 00 CV 06533 D 2003may16 Ass PDFDocument15 pagesCta 00 CV 06533 D 2003may16 Ass PDFAgnes PajilanNo ratings yet

- LB Decision in Aggarwal Color Case On Notification No. 12/2003-An AnalysisDocument5 pagesLB Decision in Aggarwal Color Case On Notification No. 12/2003-An AnalysisShrenikNo ratings yet

- Stock transactions affect economyDocument28 pagesStock transactions affect economyGreg MartinezNo ratings yet

- Where Two Provisions of The Law of The Same Hierarchy Conflicts One Another The...Document9 pagesWhere Two Provisions of The Law of The Same Hierarchy Conflicts One Another The...LDC Online ResourcesNo ratings yet

- Case NotesDocument3 pagesCase NoteskaiaceegeesNo ratings yet

- Discounts Incentives GST ImplicationsDocument12 pagesDiscounts Incentives GST ImplicationsVrajesh PatelNo ratings yet

- Incentives-GST Implications - Taxguru - in PDFDocument5 pagesIncentives-GST Implications - Taxguru - in PDFprathamesh bhatkarNo ratings yet

- Timbol and Diaz Vs Secretary of FinanceDocument2 pagesTimbol and Diaz Vs Secretary of FinancehaydeeNo ratings yet

- CIR vs Co G.R. No. 241424 Dispute Over Tax ExemptionDocument4 pagesCIR vs Co G.R. No. 241424 Dispute Over Tax ExemptionPAMELA DOLINANo ratings yet

- Service Tax: Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited Vs Union of India Overruled Its Earlier Decision inDocument3 pagesService Tax: Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited Vs Union of India Overruled Its Earlier Decision inAmita SinwarNo ratings yet

- 3-D Analysis of Madhav Steel Tax Credit CaseDocument5 pages3-D Analysis of Madhav Steel Tax Credit CaseAbhay DesaiNo ratings yet

- Corona, J.:: G.R.No.160756: March 9, 2010Document3 pagesCorona, J.:: G.R.No.160756: March 9, 2010Weena Joy C. LegalNo ratings yet

- Classifying Business Auxiliary ServicesDocument18 pagesClassifying Business Auxiliary ServicesAbhishek MehtaNo ratings yet

- Digest Cases 51-60Document6 pagesDigest Cases 51-60Vince HonarableNo ratings yet

- GST Weekly Update - 39-2023-24Document5 pagesGST Weekly Update - 39-2023-24guptaharshit2204No ratings yet

- 2022 141 Taxmann Com 223 New Delhi CESTAT 18 02 2022Document30 pages2022 141 Taxmann Com 223 New Delhi CESTAT 18 02 2022pradeepkumarsnairNo ratings yet

- Abacus Securities Corp. v. AmpilDocument13 pagesAbacus Securities Corp. v. AmpilHershey Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Villanueva V City of IloiloDocument48 pagesVillanueva V City of Iloiloamun dinNo ratings yet

- Cir Vs San Roque PowerDocument3 pagesCir Vs San Roque PowerHa MisNo ratings yet

- Deficiency of Services Under Consumer Protection Act, 2019 - Lexology PDFDocument4 pagesDeficiency of Services Under Consumer Protection Act, 2019 - Lexology PDFVarun RoyNo ratings yet

- Cirilo A. Diaz, Jr. For Petitioner. Henry V. Briguera For Private RespondentDocument42 pagesCirilo A. Diaz, Jr. For Petitioner. Henry V. Briguera For Private RespondentNikki EmmNo ratings yet

- Digestssss Second HalfDocument17 pagesDigestssss Second HalfRay PiñocoNo ratings yet

- Vouchers - GST Implication - Taxguru - inDocument5 pagesVouchers - GST Implication - Taxguru - inCA Sriram KumarNo ratings yet

- Condominium Corp Not Liable for Business TaxDocument15 pagesCondominium Corp Not Liable for Business TaxChristian Edward CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Also in Indian Oil Corp. Ltd. v. CCE, Followed in SAIL v. CCE (2012)Document3 pagesAlso in Indian Oil Corp. Ltd. v. CCE, Followed in SAIL v. CCE (2012)tripschoolNo ratings yet

- Adwitya Spaces P LTD inDocument4 pagesAdwitya Spaces P LTD ingauravNo ratings yet

- Teja Marketing vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument8 pagesTeja Marketing vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtHyacinthNo ratings yet

- Diaz V SofDocument5 pagesDiaz V SofLiana AcubaNo ratings yet

- RULING MASEMBE RONALD V AZAAN Trading LTDDocument9 pagesRULING MASEMBE RONALD V AZAAN Trading LTDMarvin TumwesigyeNo ratings yet

- VAT on Toll Fees CaseDocument7 pagesVAT on Toll Fees CaseR.A. GregorioNo ratings yet

- Doc-20231022-Wa0005 231022 090138Document9 pagesDoc-20231022-Wa0005 231022 090138kumarhealthcare2000No ratings yet

- Teja Marketing V IacDocument2 pagesTeja Marketing V IacSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Purple Wings Tax DigestsDocument36 pagesPurple Wings Tax DigestsJf LarongNo ratings yet

- Renato Diaz Vs Secretary of FinanceDocument5 pagesRenato Diaz Vs Secretary of FinanceLouis BelarmaNo ratings yet

- Service Tax AssignmentDocument9 pagesService Tax AssignmentRahat AdenwallaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Compulsory Strata Management Law in NSW: Michael Pobi, Pobi LawyersFrom EverandAn Overview of Compulsory Strata Management Law in NSW: Michael Pobi, Pobi LawyersNo ratings yet

- Civil Judge PaperDocument37 pagesCivil Judge PaperAshish GillNo ratings yet

- THE INDIAN FOREST ACTDocument24 pagesTHE INDIAN FOREST ACTSidharth SudNo ratings yet

- The National University of Advanced Legal Studies (Nuals)Document1 pageThe National University of Advanced Legal Studies (Nuals)Ashish GillNo ratings yet

- Y.sleebachen Etc Vs Superintending Engineer Wro-Pwd ... On 4 August, 2014Document8 pagesY.sleebachen Etc Vs Superintending Engineer Wro-Pwd ... On 4 August, 2014Ashish GillNo ratings yet

- Jolly Constructions Vs Housing Society LTD On 6 May, 2010Document4 pagesJolly Constructions Vs Housing Society LTD On 6 May, 2010Ashish GillNo ratings yet

- Cmmon ObjectionDocument2 pagesCmmon ObjectionAshish GillNo ratings yet

- HTL Guidelines and ProcessDocument9 pagesHTL Guidelines and ProcessAshish GillNo ratings yet

- Latest Judgment SC AugustDocument1 pageLatest Judgment SC AugustAshish GillNo ratings yet

- Maritime LegalDocument1 pageMaritime LegalAshish GillNo ratings yet

- UndertakingENGLISH20 09 2014Document1 pageUndertakingENGLISH20 09 2014Ashish GillNo ratings yet

- Complete AddressDocument10 pagesComplete AddressAshish GillNo ratings yet

- Case LawsDocument50 pagesCase LawsAshish GillNo ratings yet

- MaritimeDocument1 pageMaritimeAshish GillNo ratings yet

- CN of Media Law From JJ SirDocument13 pagesCN of Media Law From JJ SirAshish GillNo ratings yet

- DECLARATIVE and PROCEDURAL MEMORY and Explicit and ImplicitDocument2 pagesDECLARATIVE and PROCEDURAL MEMORY and Explicit and ImplicitAshish GillNo ratings yet

- 216NOTICE - Provisional Allotment To Hostels - Remittance of FeesDocument1 page216NOTICE - Provisional Allotment To Hostels - Remittance of FeesAshish GillNo ratings yet

- National Law Fest: Team Registration FormDocument1 pageNational Law Fest: Team Registration FormAshish GillNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Broadcasting Legislation in IndiaDocument40 pagesAn Overview of Broadcasting Legislation in Indiaaltlawforum100% (6)

- Student Registration FormDocument1 pageStudent Registration FormAshish GillNo ratings yet

- Assignment GuidelineDocument2 pagesAssignment GuidelineAshish GillNo ratings yet

- Maritime December 2005 PDFDocument14 pagesMaritime December 2005 PDFAshish GillNo ratings yet

- BILLOFLDDocument25 pagesBILLOFLDAshish GillNo ratings yet

- Maritime 2 8 PDFDocument18 pagesMaritime 2 8 PDFAshish GillNo ratings yet

- Bhuvanteza Happy Homes Hmda Fee ReceiptsDocument6 pagesBhuvanteza Happy Homes Hmda Fee ReceiptsMahesh KanthiNo ratings yet

- ICMAP Business Law Past PapersDocument2 pagesICMAP Business Law Past Papersmuhzahid786No ratings yet

- HRM - Assignment One - V10Document8 pagesHRM - Assignment One - V10quratulainNo ratings yet

- MINHAJ University Fee Challan for MSC-MTH StudentDocument2 pagesMINHAJ University Fee Challan for MSC-MTH StudentSo NiaNo ratings yet

- Law On Negotiable InstrumentsDocument24 pagesLaw On Negotiable InstrumentsGABRIELLA PAWANo ratings yet

- 28 Dec 2022 - 28 Dec 2022Document2 pages28 Dec 2022 - 28 Dec 2022TAJ ENTRPRISESNo ratings yet

- What is Letter of Credit? Bank Payment Tool for ExportersDocument2 pagesWhat is Letter of Credit? Bank Payment Tool for ExportersCarlos KarmunNo ratings yet

- BZU Tender for Soil Sciences Dept EquipmentDocument1 pageBZU Tender for Soil Sciences Dept Equipmentuzairiqbal800_696794No ratings yet

- RenewalPremium 35616458Document1 pageRenewalPremium 35616458Raghavendra ChinnuNo ratings yet

- Whirlpool AC InvoiceDocument2 pagesWhirlpool AC Invoicevijay mishraNo ratings yet

- Clearance Form Caution MoneyDocument2 pagesClearance Form Caution MoneyFaizan AsgharNo ratings yet

- Velaris North Unit 23H (200sqm)Document1 pageVelaris North Unit 23H (200sqm)Lean MeilyNo ratings yet

- N3552005822 SKU71 - 2 - 3552005822: Service Number IvrsDocument1 pageN3552005822 SKU71 - 2 - 3552005822: Service Number IvrsShubham NamdevNo ratings yet

- 365) - The Income Tax Rate Is 40%. Additional Expenses Are Estimated As FollowsDocument3 pages365) - The Income Tax Rate Is 40%. Additional Expenses Are Estimated As FollowsMihir HareetNo ratings yet

- Echallan MH000503223202324 EDocument1 pageEchallan MH000503223202324 Eankit trivediNo ratings yet

- Tra May 2013 AttachmentDocument10 pagesTra May 2013 AttachmentJeremiah TrinidadNo ratings yet

- H0070A0005731710 labelAndInvoiceMergeDocument2 pagesH0070A0005731710 labelAndInvoiceMergeAnupam SinghNo ratings yet

- Application details for OBC reservationDocument1 pageApplication details for OBC reservationPetas SarNo ratings yet

- Floating Rate Saving BondDocument6 pagesFloating Rate Saving Bondmanoj barokaNo ratings yet

- Invoice for Pharmaceutical ProductsDocument1 pageInvoice for Pharmaceutical Productskeylor moraNo ratings yet

- Tanggal Uraian Transaksi Nominal Transaksi SaldoDocument2 pagesTanggal Uraian Transaksi Nominal Transaksi SaldoRazor RRNo ratings yet

- Inv 407306401237Document2 pagesInv 407306401237hesima4637 bodeem.comNo ratings yet

- SharonDocument6 pagesSharonLucky LuckyNo ratings yet

- Lesson 14 Financial Literacy Andrea RDocument2 pagesLesson 14 Financial Literacy Andrea Rapi-501679979No ratings yet

- BIR RulingDocument3 pagesBIR RulingyakyakxxNo ratings yet