Professional Documents

Culture Documents

26 - Determining The Optimal Tax in Mining

Uploaded by

Matias FernandezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

26 - Determining The Optimal Tax in Mining

Uploaded by

Matias FernandezCopyright:

Available Formats

144

John E. Tilton / Natural Resources Forum 28 (2004) 144149

Natural Resources Forum 28 (2004) 144149

Determining the optimal tax on mining

John E. Tilton

Abstract

Keywords: Mining; Taxation; Ricardian rent; User costs; Non-renewable resources.

1. Introduction

UN CO

The slowdown in world economic growth over the past several years has adversely affected the mining industry, producing a decline in exploration, new mine development, and perhaps most troublingly (at least from the perspective of host governments) tax revenues, as companies struggle with lower prices and depressed prots. Despite the recovery in recent months, it is perhaps not surprising that in many mineral exporting countries public ofcials and others are searching for ways to increase the contribution of mining to the domestic economy. Nowhere is this tendency more evident than in Chile, where politicians, mining ofcials, academics, and others have for some time been debating the desirability of raising mining taxes by imposing a royalty on producers. The debate in Chile raises two important, but quite different, questions. First, should the country raise the level of taxes on its privately owned mining companies?1 And second, if so, should this be done by imposing a royalty

RR EC

The author is Professor and Chair of Mineral Economics, Mining Centre, Ponticia Universidad Catlica de Chile, Santiago, Chile; and William J. Coulter Professor of Mineral Economics, Division of Economics and Business, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, Colorado. Email: jtilton@ing.puc.cl. 1 Privately-owned mining companies, which currently account for about two-thirds of copper mine output in Chile, have seen their share of the total rise dramatically over the past 15 years. The remainder of the countrys copper mine output comes from Codelco (Corporacin del Cobre de Chile), which is owned by the Chilean State.

2004 United Nations. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

NARF2802C06

144

TE

This article examines three arguments often raised in support of higher taxes on mining and nds them wanting: First, the wealth or economic rents associated with particularly rich deposits rightfully belong to the citizens of the host country. Second, mining companies should compensate the State and the public for their use of mineral resources, given the intrinsic value arising from their non-renewable nature. Third, the division of the wealth created by mining is unfair. Too much goes to mining companies, and too little to the host country to promote economic development. It suggests instead that host governments should maximize the net present value of the social benets owing from their mineral sector. In practice, unfortunately, it is often difcult to know whether this objective is served by raising or lowering the level of taxation on mining.

(that is, a tax on total mine production measured either in terms of weight or gross revenues)? This article focuses on the rst of these two issues. Specically, it examines from an economic perspective three common arguments for increasing taxes on mining:

Some mineral deposits, as a result of the geological forces

responsible for their formation millions of years ago, are particularly rich. The wealth, or what economists call Ricardian rents, associated with these resources rightfully belongs to the people. So as companies mine rich deposits, the State should ensure that it captures the Ricardian rents for its citizens. Mineral resources are intrinsically valuable because they are non-renewable. As a result, an opportunity cost, or what economists call user cost, is incurred when such resources are exploited now, rather than saved for the future. Taxes should ensure that mining companies compensate the State and the public for their use of valuable non-renewable assets. Many mining companies are not paying enough taxes. Too much of the wealth created by mining goes to mining companies, and too little to the State to promote economic growth and development.

2. Rich deposits and Ricardian rents

Rents are dened in economics as a return to a rm or a factor of production that does not affect its behaviour. For

PR

4/5/04, 5:39 PM

OO

John E. Tilton / Natural Resources Forum 28 (2004) 144149

145

Figure 1. Ricardian rent.

example, consider a football player earning a million dollars a year, who could instead manage a restaurant for $100,000. If he is willing to play football if paid $100,000 or more, his salary contains $900,000 in rent. This sum could be taken away without affecting his behaviour, or altering the performance of the economy. Similarly, rms earn a rent when the price they receive for the good or goods they produce is above the level needed to attract them into the industry, or if they already are in the industry, to keep them from leaving. David Ricardo, a British economist, writing in the early 19th century, was one of the rst to apply the concept of rent. He pointed out that agricultural land could be separated into different classes according to its fertility, as shown in Figure 1. The best land, represented by rectangle A, can produce food at the lowest cost (OCa ). The next best land, represented by rectangle B, has somewhat higher costs (OCb), and so on. When population is small, all the food needed can be grown on the best land. The supply of the best land exceeds the demand for it; the price of food (P1) equals its production costs (OCa ); and landowners receive no rent. As population and the demand for food expand, eventually all the best land is cultivated, and it becomes necessary to use land with lower fertility. This causes the production cost, and in turn the price, of food to rise. As shown in Figure 1, the price rises to P2, the cost of producing food from land of quality G, once the latter is needed to feed the population. Farmers at this price are willing to pay the owners of better land a rent, commonly called Ricardian rent. The size of the rent depends on the gap between the market price and production cost. It is shown in Figure 1 by the rectangle that extends from the production costs for each class of land to the market price. Over the years, Henry George, a colourful 19th century American printer and economist, and others have argued that Ricardian rents are particularly appropriate targets for taxation. This is in part because taxes on rents do not alter economic behaviour, and so do not introduce inefciencies into the economy. In contrast, taxes on wages, interest, and prots (the return to labour, capital, and entrepreneurship respectively) do distort the economy. In addition, taxes on

rents seem fair or equitable. In the case that Ricardo describes, for example, why should landowners but not others benet from population growth? They have not earned the rents they reap. In no way do these rents reect wealth that landowners have created. Like parcels of land, mineral deposits are of different quality and have different production costs. So, as Ricardo noted, it is an easy step to extend his analysis of agricultural land to mining. The classes of land in Figure 1 now portray different mines, and the horizontal axis measures mine capacity rather than hectares of agricultural land. Mine A has the lowest production costs, thanks to its rich ore and other factors. Mine B has the next lowest, and so on. The area for each mine under the price line and above its costs reects its Ricardian rent. Figure 2 portrays the nature of the Ricardian rent associated with Mine B in somewhat more detail. It assumes that the mines costs (OCb) are its cash or variable costs of production. These costs reect the minimum possible variable costs of production plus the portion of the potential rent that the government is collecting through taxes and other measures. As long as the price is at or above its cash costs OCb, Mine B has, at least over the short run, an incentive to stay in operation. Consequently, at the price P2 it is earning a substantial amount of Ricardian rent. This rent can be divided into three parts. The rst (quasirent) reects the mines cost of capital and other xed inputs. It exists only in the short run. If the mine does not recover its cost of capital, including a competitive rate of return, it will not replace its capital and in the long run will cease to operate. The second (other rent) comes from several sources, which similarly create rents only in the short run. For example, metal prices tend to uctuate with the business cycle. During booms, they rise creating additional rents. Over the business cycle, however, these rents are needed to offset low prices during recessions. The third (pure rent) arises because the mine is exploiting a richer or higher quality deposit than the marginal mine (the highest cost mine in production, which is Mine G in Figure 1). The pure rent for a mine depends upon many considerations, including its ore grade, its location

NARF2802C06

UN

CO R

145

RE CT

ED

PR

4/5/04, 5:39 PM

OO

Figure 2. Rent for Mine B.

146

John E. Tilton / Natural Resources Forum 28 (2004) 144 149

(near the surface or near a port), its mineralization and ease of processing, and its associated by-products. Pure rent is normally what those advocating higher taxes have in mind when they stress the need to capture the wealth created by a countrys geological legacy for its citizens. Moreover, it is widely assumed that the government can take these rents precisely because they are rents without affecting the performance of the economy and the ability of the mineral sector to generate new wealth. No mine should close because the government takes the pure rent. This argument, however, raises two troubling issues. First, rents are found in many sectors. Ricardo, as we have seen, focused on agriculture land. Viniculture, forestry, shing, and other important sectors using natural resources also generate sizable rents. In addition, public policy creates rents. When cities, such as Santiago, for example, build additional subway lines, the owners of apartments and stores along the new routes reap sizable rents. If mining rents are to be taxed, should not the same hold for all rents, and in particular those that public policy creates? Yet rarely do those advocating the taxation of mining rents extend their proposals to other rents. Second, and more importantly, it is the discovery of rich deposits or technological developments that permit the protable exploitation of known but previously uneconomic resources that actually create rents. Of course, favourable geology is necessary. But prior to their discovery and the development of the necessary production technologies, mineral resources have no value. As a result, in the very long run there are no true rents in the mining sector. We have already seen that the quasirent and the other rent, if taken by the State, will reduce or eliminate the incentives that mining companies have to invest. Taking the pure rent similarly has adverse effects on rm behaviour. It is the hope of discovering a bonanza, a deposit so rich it can generate huge amounts of pure rent, that drives exploration. Similarly, the quest for pure rent motivates the research that creates new technologies allowing the mining and processing of known, but previously uneconomic, mineral resources. So governments that tax the pure rent (even though they carefully leave the quasirent and other rent) are doomed to watch their mineral sector slowly decline over time as their known deposits are depleted. This means that the argument for higher taxes to capture the pure rent in mining is misguided if a country wants to maintain a viable mining sector over the long run. It is worth noting as well that the presence of large Ricardian rents in the short run (the sum of the quasirent, other rent, and pure rent) coupled with the absence of such rents in the very long run creates a danger of short-sighted public policy. Higher taxes on mining will almost always appear successful for a time. (For this not to be the case, taxes would have to increase by more than the combined total of the quasirent, other rent, and pure rent.) Their adverse effects on mine production and government revenues may take years to

become apparent and then, unfortunately, take many more years, even decades, to reverse.

3. Non-renewable resources and user costs

Copper and other metal deposits are non-renewable on any time scale of relevance to the human race. Harold Hotelling, an American economist, argued in an important article published in the early 1930s (Hotelling, 1931) that a mine with a given stock of reserves will behave differently from other rms. Normally, we expect competitive rms to continue to expand their output until the cost of producing the next unit just equals the market price it receives. However, a mine in addition to its production costs must also consider the opportunity cost associated with producing one more unit of output during the current period. The latter, which arises because reserves exploited today are not available in the future, equals the net present value of the loss in future prots associated with producing one more unit of output today. Economists refer to this opportunity cost as user costs, Hotelling rent, and scarcity rent. The term user costs is preferable, and will be used here, because this cost is in fact not a rent. Mines that cannot recover their production costs plus user costs have an incentive to alter their behaviour by ceasing production. While Hotelling focused on an individual mine, others have applied his analysis to the mining sector as a whole. Figure 3 shows how this extends the previous analysis of Ricardian rents. Now, the marginal mine (Mine G) is prepared to operate only if the market price is at the level P3, sufciently high to cover both its cash costs and user costs. At a price lower than P3, it is better off keeping its reserves in the ground for use in the future. So user costs can be thought of as the value of reserves of marginal quality (the quality of Mine G) in the ground, which arises because these reserves are non-renewable. The reserves of mines with lower costs (Mines A through F), of course, are more valuable, because their value reects Ricardian rents in addition to user costs. Non-renewable resources differ from renewable resources in that they, in theory at least, have additional value arising

UN CO

RR EC

TE

NARF2802C06

146

PR

4/5/04, 5:39 PM

OO

Figure 3. User costs.

John E. Tilton / Natural Resources Forum 28 (2004) 144 149

147

CO R

from their non-renewable nature, a value measured by their user costs. Since the mineral resources in many countries belong to the State, one can argue that mining companies consuming these assets should compensate the State, presumably by a tax that captures user costs. The problem in practice with this argument is that available evidence suggests that user costs are negligible for copper and most other mineral commodities, including even oil (Adelman, 1990; Cairns, 1998; Kay and Mirrless, 1975). While Hotellings individual mine must inevitably run out, this is not the case for the world as a whole. The amount of copper in the earths crust equals some 120 million years of current consumption (Tilton, 2002). When compared to the several hundred thousand years that the human race has existed, this is a long time. Moreover, copper and other metals are not destroyed when used. They can be recycled and reused. Of course, production costs might rise over time, though even this is not certain, given the new technologies and other forces that tend to push costs down. The important point is that the market apparently does not worry about the negative effects of production today on the future prots of mining. While mineral deposits are from time to time sold, sometimes for substantial amounts, the sale price reects the magnitude of the associated Ricardian rent. Even when marginal deposits (such as those of Mine G, that would be expected to just break even if developed) are sold, the price typically reects an option value, which may be positive, as there is some probability that the market price will rise sufciently in the future to generate Ricardian rent. In short, it is Ricardian rent not user costs that apparently gives value to mineral resources in the ground. One reason for this is uncertainty, particularly regarding future technological developments. History shows that saving for the future reserves that can be protably exploited today, is risky. The nitrate deposits of Chile became worthless in the early 20th century, not because of depletion, but because new technology created a more attractive substitute. Over the past several decades, the rise of low-cost ocean transportation for bulk commodities coupled with discovery of rich iron ore deposits in Australia and Brazil has similarly undermined the economic viability of many iron ore deposits in North America and Europe. If user costs are insignicant, then the value of mineral resources stemming from their non-renewable nature is similarly insignicant. This calls into question the case for raising taxes on mining because mining is exploiting a valuable, non-renewable resource that belongs to the public.

because many of the new mines that have started operations over the past 10 years are paying quite modest taxes.2 This is due, in part, to the benets of accelerated depreciation, which the tax laws permit as a means of encouraging investment. By allowing a company to depreciate its assets more quickly, accelerated depreciation delays the payment of taxes. Given the time value of money, this lightens the tax burden. But this is only part of the explanation. Chile also provides a relatively favourable climate for private investors in mining. Comparisons of tax regimes invariably place Chile at or near the top with respect to competitiveness (Otto et al., 2000; Naito et al., 2001). When the Fraser Institute conducts its annual survey asking exploration managers of mining companies to grade countries and States for their investment potential, Chile similarly comes out at or near the top (Fredricksen, 2002). This suggests that the taxes on mining in Chile, at least relative to other countries with similar geological potential and risks, are low. Does this mean that mining taxes should be higher in Chile and other States with similarly favourable scal regimes? That the current allocation of the wealth created by mining between the companies and the government in these countries is unfair? The answer, unfortunately, is not clear. Since fairness, like beauty, is a subjective concept over which informed and reasonable people can disagree, it is more useful to frame the issue in a slightly different way. As sovereign States, mineral producing nations should pursue taxation and other policies that achieve, to the maximum extent possible, the goals and objectives they have for their mineral sector. For private companies, economics normally assumes that the goal, or objective function, is to maximize prots. Over time, this means maximizing the net present value of a company or its wealth creation. The goal of public policy, of course, is different. Mining countries presumably want to use their mineral wealth to promote the welfare of their citizens. While views may differ over the specic means needed to accomplish this general goal, one reasonable possibility is for the government to pursue taxation policies designed to maximize the net present value of the stream of revenues owing from the mining sector to the government over time.3 The government can then use these revenues to support education, housing, health

4. The optimal tax and allocation of rents

More difcult to assess is the third reason advanced for raising mining taxes, the concern that mining companies are not paying enough taxes and so are not providing the host country with a fair share of the wealth owing from its mineral sector. In Chile, for example, this concern arises

NARF2802C06

UN

147

RE CT

2

ED

Recently the Consejo Minero, the trade association for the large mining companies in Chile, publicized the prots earned and the taxes paid in 2002 by their member companies. The 18 investor-owned members earned prots after taxes totalling US$437 million. They paid US$ 107 million in taxes, or approximately 20% of before tax prots. However, three companies accounted for most of these taxes (El Mercurio, 2003). 3 Of course, the objective function of mineral policy may include job creation, regional development, and other variables in addition to the revenues the mineral sector pays to the government. In this case, the net present value of the social benets from the mineral sector, which reects all of the desired goals properly weighted for their relative importance, should replace the net present value of government revenues as the goal or objective of mining taxation policy in the analysis that follows.

PR

4/5/04, 5:39 PM

OO

148

John E. Tilton / Natural Resources Forum 28 (2004) 144 149

Figure 4. The optimal tax rate.

5. Conclusions

services, infrastructure, and other goods and services that enhance the well-being of its people. In this case, we know that the optimal tax rate, measured as a percentage of prots or wealth generated by the mineral sector, is not zero, since this would produce no government revenues. As the tax rate rises from zero to some optimal level (T*), as the modied Laffer curve in Figure 4 shows,4 the net present value of the stream of current and future government revenues increases. Once the optimal level is reached, however, any further increase in the tax rate will cause companies to cut their exploration for new deposits, to stop developing new mines, and eventually, if the tax rate is pushed high enough, to close their existing mines. These developments cause the net present value of government revenues to decline, and eventually to fall to zero. Raising the tax rate above the optimum at rst reduces the prolicacy and then kills the goose that lays the golden eggs. The critical question is, whether current taxes on mining are below or above the optimum rate T*. If below, mining companies are not paying enough from the perspective of society, and the tax rate should be raised. Mineral producing countries have the right, and indeed their governments presumably have the obligation, to pursue policies that ensure that their resources contribute the maximum possible to the welfare of their citizens and society as a whole. However, if the current tax rate is above the optimum, attempts to raise it further will be counterproductive, and the result will be a reduction in the net present value of tax revenues. In this situation, a lightening of the tax rate is not just good for mining rms, it is also good for the country as a whole. So we need to know more about the actual shape of the relationship between the tax rate and the net present value of government revenues the curve shown in Figure 4 and just where the optimum tax rate is. The relatively favourable mining tax regime and investment climate found in Chile and certain other mining States may suggest to some that the actual tax rate is below the optimum in these

UN CO

Over the past two decades, favourable tax regimes and mineral policies have encouraged private investors to develop many new mines in Chile and a few other countries. These countries have attracted the lions share of the global investment in this sector. Despite this success, or perhaps because of it, some are now proposing that these countries change their policies, and in particular raise their taxes on mining, for various reasons. Arguments for higher taxes based on the Ricardian rents associated with some mineral deposits or on their nonrenewable nature, it has been argued here, are unconvincing. The appropriate approach is to assess the change in the net present value of tax revenues or more generally the net present value of the social benets that an increase in the tax rate would produce. The problem here, however, is the difculty of determining whether the tax rate is currently above or below the optimum. A higher tax rate shifts tax revenues over time, from the more distant future to the present and near future. This means that a tax increase is easier to justify if the interests of society are focused largely on the present generation and in particular its welfare over the next several years. In this case, tax revenues in the more distant future are heavily discounted. However, if the welfare of the current generation beyond the next few years and the welfare of future generations are of concern as well, then the longer run negative effects of an increase in the tax rate arising from the reduction in exploration and new mine development become important. In this case, the short-run gains in tax revenues are less likely to offset the longer-run losses sufciently to enhance the welfare of society.

RR EC

The Laffer curve, which shows the relationship between the tax rate and tax revenues, highlights the fact that, as the tax rate rises, tax revenues will rst rise and then fall (as higher rates eventually reduce the incentives of people to work). The curve was proposed by the U.S. economist Arthur Laffer.

NARF2802C06

148

TE

D

References

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Adelman, M.A., 1990. Mineral depletion, with special reference to petroleum. Review of Economics and Statistics 72(1): 110.

PR

4/5/04, 5:39 PM

OO

countries and should be raised. But this is not necessarily so. Thanks to these favourable conditions, mining in these countries has expanded rapidly over the past two decades. Whether this would have been the case, had mining taxes been higher, is simply unknown. Without such information, as well as information on the implications for future investments, we cannot be sure that a higher tax rate would raise, rather than lower, the net present value of mining taxes, even in those countries with favourable tax policies.

John E. Tilton / Natural Resources Forum 28 (2004) 144 149 Cairns, R.D., 1998. Are mineral deposits valuable? A reconciliation of theory and practice. Resources Policy 24(1): 19 24. El Mercurio, 2003. Tres mineras concentraron el 73% de los impuestos en 2002. 8 July. Fredericksen, L., 2002. Annual Survery of Mining Companies, 2002/2003. The Fraser Institute, Vancouver, BC. This document is available on line at www.fraserinstitute.ca/shared/readmore.asp?sNav=ph&id=459. Hotelling, H., 1931. The economics of exhaustible resources. Journal of Political Economy 39(2): 137175. Kay, J.A., Mirrlees, J.A., 1975. On comparing monopoly and competition in exhaustible resource exploitation. In: Pearce, D.W. (Ed.), The

149

NARF2802C06

UN

CO R

149

RE CT

4/5/04, 5:39 PM

ED

PR

OO

Economics of Natural Resource Depletion. Macmillan, London. 140 176. Naito, K., Remy, F., Williams, J., 2001. Review of Legal and Fiscal Frameworks for Exploration and Mining. Mining Journal Books, London. Otto, J.M., Batarseh, M.L., Cordes, J., 2000. Global Mining Taxation Comparative Study, 2nd edition. Institute for Global Resources Policy and Management, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO. Tilton, J.E., 2002. On Borrowed Time? Assessing the Threat of Mineral Depletion. Resources for the Future, Washington, DC.

You might also like

- Mining RoyaltiesDocument12 pagesMining RoyaltiesChristos VoulgarisNo ratings yet

- Rent Inequality and TaxDocument37 pagesRent Inequality and TaxNishat FarzanaNo ratings yet

- Income DiversityDocument10 pagesIncome DiversitybilaldboukNo ratings yet

- Creating Wealth and Competitivenes in MiningDocument23 pagesCreating Wealth and Competitivenes in MiningEmilio Castillo DintransNo ratings yet

- The Energy Charter Treaty: Governing International Energy InvestmentDocument26 pagesThe Energy Charter Treaty: Governing International Energy InvestmentgmassabieNo ratings yet

- International Rules For Trade in Natural ResourcesDocument9 pagesInternational Rules For Trade in Natural ResourcesTeonelito Balbin BatutayNo ratings yet

- Ingles para Los Negocios DraftDocument31 pagesIngles para Los Negocios DraftmarialuciaduranlNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of The Mining Boom: Where Did They Go?Document15 pagesThe Benefits of The Mining Boom: Where Did They Go?Augusto IabrudiNo ratings yet

- David Ricardo 2Document39 pagesDavid Ricardo 2Elena Lavinia IalomiteanuNo ratings yet

- O Ocidente Diz Adeus Ao Capitalismo IndustrialDocument31 pagesO Ocidente Diz Adeus Ao Capitalismo IndustrialMarcelo AraújoNo ratings yet

- Global Trade NotesDocument5 pagesGlobal Trade NotesSofia CastilloNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Land Acquisition ManagementDocument7 pagesAssignment On Land Acquisition ManagementNehaBajajNo ratings yet

- David RicardoDocument4 pagesDavid RicardoHydee Magno FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Eminent Domain in Kelo v. New LondonDocument7 pagesAnalysis of Eminent Domain in Kelo v. New Londoncynthia awuorNo ratings yet

- Combined-Cycle Power PlantsDocument22 pagesCombined-Cycle Power PlantsAnonymous Iev5ggSRNo ratings yet

- Commodity Prices and FP in LAC, Sinnott 2009Document41 pagesCommodity Prices and FP in LAC, Sinnott 2009Sui-Jade HoNo ratings yet

- WP Mit 2016 PDFDocument36 pagesWP Mit 2016 PDFLucas BalestraNo ratings yet

- Module 3auditing Mining Industry FinalDocument25 pagesModule 3auditing Mining Industry FinalNicole Ann MercurioNo ratings yet

- Market Mechanisms and Supply Adequacy in The Power Sector in Latin AmericaDocument38 pagesMarket Mechanisms and Supply Adequacy in The Power Sector in Latin AmericadanielraqueNo ratings yet

- Privatisation Definitions and Forms: Royal Mail Case StudyDocument6 pagesPrivatisation Definitions and Forms: Royal Mail Case StudyKunal SharmaNo ratings yet

- Global Witness RIGGED The Scramble For Africas Oil Gas and Minerals 1Document44 pagesGlobal Witness RIGGED The Scramble For Africas Oil Gas and Minerals 1chinemeikeNo ratings yet

- IELR - Resource Nationalism - A Gathering Storm - Mark Clarke Tom CumminsDocument7 pagesIELR - Resource Nationalism - A Gathering Storm - Mark Clarke Tom CumminsdumbledoreaaaaNo ratings yet

- MACR QuizDocument6 pagesMACR QuizHarshita PareekNo ratings yet

- Crude Calculations AppendixDocument16 pagesCrude Calculations AppendixAnonymous AvkIw8No ratings yet

- Working Paper in The Role of Foreign Direct Investment in Resource-Rich RegionsDocument73 pagesWorking Paper in The Role of Foreign Direct Investment in Resource-Rich RegionsFederico PachecoNo ratings yet

- Eco Tax ProjectDocument23 pagesEco Tax ProjectRishi RameshNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - NotesDocument5 pagesChapter 2 - Notesswati DesaiNo ratings yet

- Economic ResourcesDocument28 pagesEconomic Resourcesayub_balticNo ratings yet

- Colombia FTAs Aggravate ConflictsDocument9 pagesColombia FTAs Aggravate ConflictsLaauu KaasteellaanosNo ratings yet

- The Case of Artisanal Mining in Bolivia: Local Participatory Development and Mining Investment OpportunitiesDocument13 pagesThe Case of Artisanal Mining in Bolivia: Local Participatory Development and Mining Investment OpportunitiesThamani GemsNo ratings yet

- 68 - Minerals in Bolivian Development 1970-90 - AutyDocument17 pages68 - Minerals in Bolivian Development 1970-90 - Autyfedenacif6788No ratings yet

- TTPC2009 BookletDocument54 pagesTTPC2009 BookletSam_1_No ratings yet

- #3. Trinidad and Tobago Case StudyDocument5 pages#3. Trinidad and Tobago Case StudyOrrin John-BaptisteNo ratings yet

- Electric Sector Deregulation and Restructuring in Latin AmericaDocument5 pagesElectric Sector Deregulation and Restructuring in Latin AmericaCamilo RomeroNo ratings yet

- Review IEDocument12 pagesReview IENgọc AnhNo ratings yet

- What Conditions Made Possible The Emergence of A World Economy' in The Latter 19 Century? How Far Were The Benefits Distributed Equitably?Document5 pagesWhat Conditions Made Possible The Emergence of A World Economy' in The Latter 19 Century? How Far Were The Benefits Distributed Equitably?Gabriel LambertNo ratings yet

- David RicardoDocument11 pagesDavid RicardoIshrat Jahan DiaNo ratings yet

- File Comp Mining Tax RegimeDocument12 pagesFile Comp Mining Tax Regimeatcher01No ratings yet

- Coal We Can't Wait Report - 0Document8 pagesCoal We Can't Wait Report - 0The Wilderness SocietyNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 12 00626 v2Document20 pagesSustainability 12 00626 v2Huda AliNo ratings yet

- Market Failure Model AnswerDocument7 pagesMarket Failure Model Answerkala1975No ratings yet

- Kilburn Manifesto 10 Energy Beyond NeoliberalismDocument22 pagesKilburn Manifesto 10 Energy Beyond NeoliberalismPeter ClarkeNo ratings yet

- Mining Royalties, Global Study of Their Impact On Investors, Government, and Civil SocietyDocument320 pagesMining Royalties, Global Study of Their Impact On Investors, Government, and Civil SocietydaveanthonyNo ratings yet

- Leasing CH 1Document10 pagesLeasing CH 1ahong100No ratings yet

- Forces For Good - Town & Country Planning ArticleDocument4 pagesForces For Good - Town & Country Planning ArticleJulian DobsonNo ratings yet

- "Economic Development Strategies For Fracking: The Case of The Tuscaloosa Marine Shale Play" by Chad R. Miller and Joel F. BoltonDocument23 pages"Economic Development Strategies For Fracking: The Case of The Tuscaloosa Marine Shale Play" by Chad R. Miller and Joel F. BoltonThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- Nadia Cuffaro and David HallamDocument17 pagesNadia Cuffaro and David HallamghazigilaniNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3: Trade Theories: BBC 1200 - International Business and Trade 2 SEM 2019-2020Document19 pagesLesson 3: Trade Theories: BBC 1200 - International Business and Trade 2 SEM 2019-2020unknownNo ratings yet

- The Green Collar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest ProblemsFrom EverandThe Green Collar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest ProblemsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (32)

- Oil and Gas Industry ReportDocument3 pagesOil and Gas Industry ReportKumala Galuh HaivaNo ratings yet

- 701 Drazen AssignmentDocument27 pages701 Drazen AssignmentAshu Inder SharmaNo ratings yet

- Questions To ConsiderDocument26 pagesQuestions To ConsiderAlex BroadbentNo ratings yet

- Ricardo - Economic Rent and Opportunity CostDocument7 pagesRicardo - Economic Rent and Opportunity CostavinashsekarNo ratings yet

- Carbon MarketsDocument6 pagesCarbon Marketsubaidsaqib02No ratings yet

- Ricardian Theory of Rent ExplainedDocument15 pagesRicardian Theory of Rent ExplainedNelson RitchilNo ratings yet

- UW Board of Regents Discusses Landed Property and Royalty vs Rent DistinctionDocument14 pagesUW Board of Regents Discusses Landed Property and Royalty vs Rent DistinctionBlasNo ratings yet

- Bolivia Nationalizes The Oil and Gas SectorDocument6 pagesBolivia Nationalizes The Oil and Gas SectorAnonymous kayEII5NNo ratings yet

- CH 16Document38 pagesCH 16tomas PenuelaNo ratings yet

- Todo JuntoDocument9 pagesTodo JuntoMatias FernandezNo ratings yet

- Industry Report FinalDocument8 pagesIndustry Report FinalMatias FernandezNo ratings yet

- Outsourcing Journal Q4-15 Nearshoring SSCDocument14 pagesOutsourcing Journal Q4-15 Nearshoring SSCMatias FernandezNo ratings yet

- Histograma CutDocument3 pagesHistograma CutMatias FernandezNo ratings yet

- Boxplot ZmcutDocument4 pagesBoxplot ZmcutMatias FernandezNo ratings yet

- Grade Tonne Report Cui Ue1-2 Tr1Document2 pagesGrade Tonne Report Cui Ue1-2 Tr1Matias FernandezNo ratings yet

- Size Wise Tax Classification in SAP (is-AFS)Document13 pagesSize Wise Tax Classification in SAP (is-AFS)Anupa Wijesinghe83% (6)

- Intacc Chap 16 ReviewerDocument8 pagesIntacc Chap 16 ReviewerJea XeleneNo ratings yet

- Train Infographic Income Tax 01102018Document3 pagesTrain Infographic Income Tax 01102018John Elnor Pable JimenezNo ratings yet

- Public RevenueDocument90 pagesPublic RevenuekhanjiNo ratings yet

- Buckwold12e Solutions Ch11Document40 pagesBuckwold12e Solutions Ch11Fang YanNo ratings yet

- Investment Undertakings PDFDocument64 pagesInvestment Undertakings PDFDianneNo ratings yet

- January 2023 QP - Paper 2 Edexcel Economics IGCSE-2-20Document19 pagesJanuary 2023 QP - Paper 2 Edexcel Economics IGCSE-2-20Irfan AhmedNo ratings yet

- Oracle R12 EBTax BR100Document19 pagesOracle R12 EBTax BR100orafinr12docs100% (2)

- OutlineDocument71 pagesOutlineMaxwell NdunguNo ratings yet

- Module 4Document59 pagesModule 4Radhi PandyaNo ratings yet

- AFITDocument409 pagesAFITBenNo ratings yet

- Concepts in Federal Taxation 2017 24th Edition Murphy Solutions Manual 1Document73 pagesConcepts in Federal Taxation 2017 24th Edition Murphy Solutions Manual 1hiedi100% (34)

- (OPINION) Train Law: What Does It Change?: Tax Reform For Acceleration and Inclusion (Train) LawDocument10 pages(OPINION) Train Law: What Does It Change?: Tax Reform For Acceleration and Inclusion (Train) Lawksulaw2018No ratings yet

- The Evolution of Citizenship Laws and Determinants of ChangeDocument89 pagesThe Evolution of Citizenship Laws and Determinants of ChangeBianca AntalNo ratings yet

- SPED To V4Document73 pagesSPED To V4ptsteixe_No ratings yet

- Corporate Finance and The Financial ManagerDocument69 pagesCorporate Finance and The Financial ManagerHuy PanhaNo ratings yet

- Appraisal Methods Real EstateDocument32 pagesAppraisal Methods Real Estateanujpundir2006100% (2)

- CHP 4 EconDocument10 pagesCHP 4 Econld123456No ratings yet

- ch24 PDFDocument23 pagesch24 PDFAlvandy PurnomoNo ratings yet

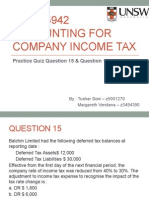

- ACCT5942 Week4 PresentationDocument13 pagesACCT5942 Week4 PresentationDuongPhamNo ratings yet

- BDO Knows ASC 740 Intra Entity Transfers of Assets Other Than Inventory - FINAL PDFDocument9 pagesBDO Knows ASC 740 Intra Entity Transfers of Assets Other Than Inventory - FINAL PDFUlii PntNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15 - Taxation and Corporate IncomeDocument26 pagesChapter 15 - Taxation and Corporate Incomewatts1No ratings yet

- Quiz 1Document46 pagesQuiz 1linerz0% (1)

- NYC Tax Class - 2 - GuideDocument20 pagesNYC Tax Class - 2 - GuideAvi GoodsteinNo ratings yet

- CH 06 - Analyzing Operating ActivitiesDocument49 pagesCH 06 - Analyzing Operating Activitieshy_saingheng_760260985% (13)

- 2022 Cost of Living Report (Portland Business Alliance)Document4 pages2022 Cost of Living Report (Portland Business Alliance)KGW NewsNo ratings yet

- DH 847Document13 pagesDH 847rishab agarwalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document6 pagesChapter 4Ashanti T Swan0% (1)

- Merchandising and ManufacturingDocument3 pagesMerchandising and ManufacturingCELINE ANNE CAPANGYARIHANNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Principles of Taxation For PDFDocument20 pagesTest Bank For Principles of Taxation For PDFAshNor RandyNo ratings yet