Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Forests of India

Uploaded by

Śáńtőśh MőkáśhíOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Forests of India

Uploaded by

Śáńtőśh MőkáśhíCopyright:

Available Formats

Forests of India The 'jungles' of India are ancient in nature and composition.

They are rich in variety and shelter a wide range of avifauna and mammals and insects. The fact that they have existed for very long time is proved from the ancient texts all of which have some mention of the forests. The people revered forests and a large number of religious ceremonies centred on trees and plants. Even today in parts of India the sacred groves exist and are worshipped. When Chandra Gupta Maurya came to power around 300 BC, he realized the importance of the forests and appointed a high officer to look after the forests. He launched the concept of afforestation on a large scale. These rules continued even during the Gupta period. During the Muslim invasions a large number of people had to flee from the attacks and take refuge in the forests. This was the beginning of a phase of migration to the forest. They cleared vast areas of forests to make way for settlements. The Muslim invaders were all keen hunters and therefore had to have patches of forests where they could go hunting. This ensured that the trees in these areas were not felled, and the forest ecology was not tampered with. During the early part of the British rule, trees were used for timber and forests were cut for paper. Large numbers of trees such as the sal, teak, and sandalwood were cut for export also. The history of modern Indian forestry was a process by which the British gradually appropriated forest resources for revenue generation. Trees could not be felled without prior permission and knowledge of the authority. This step was taken to ensure that they were the sole users of the forest trees. But after some time, the British began to regulate and conserve. In 1800, a commissioner was appointed to look into the availability of teak in the Malabar forests. In 1806, the Madras government appointed Capt. Watson as the commissioner of forests for organizing the production of teak and other timber suitable for the building of ships. In 1855, Lord Dalhousie framed regulations for conservation of forest in the entire country. Teak plantations were raised in the Malabar hills and acacia and eucalyptus in the Niligiri Hills. In Bombay, the conservator of forest, Gibson, tried to introduce rules prohibiting shifting cultivation and plantation of teak forests. From 1865 to 1894, forest reserves were established to secure material for imperial needs. From the 18th century, scientific forest management systems were employed to regenerate and harvest the forest to make it sustainable. Between 1926 and 1947 afforestation was carried out on a large scale in the Punjab and Uttar Pradesh. In the early 1930s, people began showing interest in the conservation of wild life.Around the same time the Indian rulers of the States also started conservation of habitats to help conserve the birds and mammals. Though all of them were hunters and between them and the British they cleaned at least 5000 tigers if not more. But still these areas of conservation helped save the species from extinction and formed most of the modern National Parks. The new Forest Policy of 1952 recognized the protective functions of the forest and aimed at maintaining one-third of India's land area under forest. Certain activities were banned and grazing restricted. Much of the original British policy was kept in place, such as the classification of forest land into two broad types. The next 50 years saw development and change in people's thinking regarding the forest. A constructive attitude was brought about through a number of five-year plans. Until 1976, the forest resource was seen as a source of earning money for the state and therefore little was spent in protecting it or looking after it. Today India's forests are protected in National Parks like Corbett and Nagarhole or in Sanctuaries like Pakhui and Little Rann of Katch. The modern way of thinking has resulted in Biosphere Reserves and Biodiversity Hotspots and extensive research on them have resulted in rediscovery of new species of mammals like the Leaf Deer in Arunachal Pradesh or the Hook Nosed Frog in Western Ghats.

Supporting more than 14 percent of the wild fauna and a higher percentage of the wild flora of the world the forests of India is an intricate web of life with many surprises to explore. As we proceed to an era of advanced wildlife management and as the pressure on the forests all over the world increase the need of the hour is to realize the potential resource that the forests have both economically and from the natural point of view. History of forests in India There is enough evidence to show that dense forests once covered India. The changing forest composition and cover can be closely linked to the growth and change of civilizations. Over the years, as man progressed the forest began gradually depleting. The growing population and mans dependence on the forest have been mainly responsible for this.All ancient texts have some mention of the forest and the activities that were performed in these areas. Forests were revered by the people and a large number of religious ceremonies centred on trees and plants. The Agni Purana, written about 4000 years ago, stated that man should protect trees to have material gains and religious blessings. Around 2500 years ago, Gautama Buddha preached that man should plant a tree every five years. Sacred groves were marked around the temples where certain rules and regulations applied.When Chandra Gupta Maurya came to power around 300 BC, he realized the importance of the forests and appointed a high officer to look after the forests. Ashoka stated that wild animals and forests should be preserved and protected. He launched programmes to plant trees on a large scale. These rules continued even during the Gupta period.

Types of Forest in India

More on Types of Forest in India

Rain Forests of India Himalayan subtropical pine forests Indian Tidal or Mangrove Forests

Tropical Rain Forest

Highlands Moist Deciduous Eastern Forests

Temperate Deciduous Forests East Deccan Dry Evergreen Forests Indian Deciduous or Monsoon Forests

Indian Dry Deciduous Forests

Varied types of forests are found in the Indian subcontinent. Primarily, there are 6 major groups, namely, Moist Tropical, Dry Tropical, Montane Sub Tropical, Montane Temperate, Sub Alpine, and Alpine. These are further subdivided into 16 major types of forests. Evidently, India has a diverse range of forests: from the rainforest of Kerala in the south to the alpine pastures of Ladakh in the north, from the deserts of Rajasthan in the west to the evergreen forests in the northeast. While classifying the forests into different types, the main factors taken into consideration include soil type, topography, and elevation. Forests are also classified according to their nature, the type of climate in which they thrive and its relationship with the surrounding environment. One such way is in terms of the Biome in which they exist combined with leaf longevity of the dominant species (whether they are evergreen or deciduous). Another distinction is whether the forests composed predominantly of coniferous (needle-leaved) trees, broadleaf trees, or mixed. There is no universally accepted or set principle to classify forests. The different types of forests in India are discussed below. Rainforests are those forests which are characterised by high rainfall between 1750mm and 2000mm and belong to the tropical wet climate group.

The various types of forests in India are discussed below: Tropical Rain Forest in India Tropical Rain Forests maybe called the lowland equatorial evergreen rain forests. These forests incur heavy showers of 100-600cm a year, and hence the name, Rainforests. For this reason, the soil can be poor because high rainfall tends to leach out soluble nutrients. These forests experience an average temperature of about 26 degrees Celsius, with no pronounced cold or dry spells. The quantity of life found in these forests and its diversity makes them vital. Some of the strangest and most beautiful plants and animals are found in rain forests. They also contain a large amount of natural medicines. Rainforests are dominated by the broad-leaved evergreen trees, which form a leafy canopy over the forest floor. Taller trees, called emergent, may rise above the canopy. Coffee, chocolate, banana tree, mango tree, papaya tree, avocados and sugarcane all originally came from tropical rainforests, and are still mostly grown on plantations in regions that were formerly primary forests. Temperate Deciduous Forests in India Temperate Deciduous Forests are those, which consist of predominantly broad-leafed trees. Deciduous forests are of two types: Temperate and Tropical. Temperate deciduous forests occur in areas of moderate temperature and rainfall with cold winters. Species belonging to these forests drop leaves in autumn. The deciduous forests in tropical areas shed leaves only by December (in the Northern Hemisphere) when water becomes scarce. The tropical monsoon deciduous forests are found in areas receiving annual rainfall of 100 to 200cms in India, with a distinct dry and rainy seasons and a small range of temperature. The deciduous forest can further be divided into Moist and Dry.

Moist Deciduous Forests in India The moist deciduous forests are found throughout India except in the western and the north-western regions. They occur on the wetter western side of the Deccan Plateau, the north-eastern part of the Deccan Plateau and the lower slopes of the Himalayan Mountain, on the Siwalik Hills from Jammu in the west to West Bengal In the east. The trees have broad trunks, are tall and have branching trunks and roots to hold them firmly to the ground. These forests are dominated by Sal and Teak, along with Mango, Bamboo and Rosewood. Dry Deciduous Forests in India Indian Dry Deciduous Forests are found throughout the northern part of the country except in the Northeast. It is also found in Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. The canopy of the trees does not normally exceed 25 metres. The principal trees of these forests are Indian Teak Tree, Sal, Sandalwood, Mahua, Khair, Mango, Jackfruit, Wattle and Arjun, Semal, Myrobalan and Banyan Tree.

Moreover, Littoral and swamps are scattered through out the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, as well as the delta area of the Brahmaputra River and the River Ganga. Usually, mangrove dates, whistling pines, bullet wood and royal palm tree are predominant here. They contain roots that have of soft tissue so that the plant can obtain oxygen from the water. Geographical Distribution of Indian Forests Eastern zone consists of moist, deciduous and wet evergreen forests. The Western zone forms the other extreme. It comprises mainly of thorn and dry deciduous forests. Northern and Central zones consist mainly of dry and moist deciduous forests. Southern zone incorporates characteristics of both Western and Central zones. It comprises mainly of thorn dry and eastern highlands moist deciduous forests. Forests are mostly exclusive and they are indispensable in further existence of life. Forests serve as a home to many species. Deforestation is the reason of global warming. To prevent that problem Government of India has taken many necessary steps for the plantation of trees.

Recent developments in Indian forestry

Over the last 20 years, India has reversed the deforestation trend. Specialists of the United Nations report India's forest as well as woodland cover has increased. A 2010 study by the Food and Agriculture Organization ranks India amongst the 10 countries with the largest forest area coverage in the world (the other nine being Russian Federation, Brazil, Canada, United States of America, China, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Australia, Indonesia and [5] Sudan). India is also one the top 10 countries with the largest primary forest coverage in the world, according to this study.From 1990 to 2000, FAO finds India was the fifth largest gainer in forest coverage in the world; while from 2000 [5] to 2010, FAO considers India as the third largest gainer in forest coverage. Some 500,000 square kilometres, about 17 percent of India's land area, were regarded as Forest Area in the early 1990s. In FY 1987, however, actual forest cover was 640,000 square kilometres. Some claim, that because more than 50 percent of this land was barren or bushland, the area under productive forest was actually less than 350,000 square kilometres, or approximately 10 percent of the country's land area.India's 0.6 percent average annual rate of deforestation for agricultural and nonlumbering land uses in the decade beginning in 1981 was one of the lowest in the world and on a par with Brazil.

Distribution of forests in India

A protected forest in Madhya Pradesh, Van Vihar National Park

Hinglajgarh Forest

Forest around a lake in the Western Ghats of India

India is a large and diverse country. Its land area includes regions with some of the world's highest rainfall to very dry deserts, coast line to alpine regions, river deltas to tropical islands. The variety and distribution of forest vegetation is large: there are 600 species ofhardwoods, including sal (Shorea robusta). India is one of the 12 mega biodiverse regions of the world. Indian forests types include tropical evergreens, tropical deciduous, swamps, mangroves, subtropical, montane, scrub, sub-alpine and alpine forests. These forests support a variety of ecosystems with diverse flora and fauna. [edit]Forest

cover measurement methods

Prior to 1980s, India deployed a bureaucratic method to estimate forest coverage. A land was notified as covered under Indian Forest Act, and then officials deemed this land area as recorded forest even if it was devoid of vegetation. By this forest-in-name-only method, the total amount of recorded forest, per official Indian records, was [6] 71.8 million hectares. Any comparison of forest coverage number of a year before 1987 for India, to current forest coverage in India, is thus meaningless; it is just bureaucratic record keeping, with no relation to reality or meaningful comparison. In the 1980s, space satellites were deployed for remote sensing of real forest cover. Standards were introduced to classify India's forests into the following categories:

Forest Cover: defined as all lands, more than one hectare in area, with a tree canopy density of more than 10 percent. (Such lands may or may not be statutorily notified as forest area).

Very Dense Forest: All lands, with a forest cover with canopy density of 70 percent and above Moderately Dense Forest: All lands, with a forest cover with canopy density of 40-70 percent Open Forest: All lands, with forest cover with canopy density of 10 to 40 percent Mangrove Cover: Mangrove forest is salt tolerant forest ecosystem found mainly in tropical and sub-tropical coastal and/or inter-tidal regions. Mangrove cover is the area covered under mangrove vegetation as interpreted digitally from remote sensing data. It is a part of forest cover and also classified into three classes viz. very dense, moderately dense and open.

Non Forest Land: defined as lands without any forest cover

Scrub Cover: All lands, generally in and around forest areas, having bushes and or poor tree growth, chiefly small or stunted trees with canopy density less than 10 percent Tree Cover: Land with tree patches (blocks and linear) outside the recorded forest area exclusive of forest cover and less than the minimum mapable area of 1 hectare Trees Outside Forests: Trees growing outside Recorded Forest Areas

The first satellite recorded forest coverage data for India became available in 1987. India and the United States cooperated in 2001, using Landsat MSS with spatial resolution of 80 meters, to get accurate forest distribution data. India thereafter switched to digital image and advanced satellites with 23 meters resolution and software processing of images to get more refined data on forest quantity and forest quality. India now assesses its forest distribution data biennially. The 2007 forest census data thus obtained and published by the Government of India suggests the five [6] states with largest area under forest cover as the following:

Madhya Pradesh: 7.64 million hectares

Arunachal Pradesh: 6.8 million hectares Chhattisgarh: 5.6 million hectares Orissa: 4.83 million hectares Maharashtra: 4.68 million hectares

Biodiversity in Indian forests

Asian paradise flycatcher- A bird found in the forests of Himachal Pradesh

Spotted Owlet - one of over 1000 bird species in Indian forests

Asian Golden cat, one of the 15 feline species found in India

Chestnut headed bee-eaters, found in Himalayan states of India

Indian forests are more than trees and an economic resource. They are home to some of earth's unique flora and fauna. Indian forests represent one of the 12 mega biodiverse regions of the world. India's Western Ghats and Eastern Himalayas are amongst the 32 biodiversity hotspots on earth. India is home to 12 percent of world's recorded flora, some 47000 species of flowering and non-flowering [10] plants. Over 59000 species of insects, 2500 species of fishes, 17000 species of angiosperms live in Indian forests. About 90000 animal species, representing over 7 percent of earth's recorded faunal species have been found in Indian forests. Over 4000 mammal species are found here. India has one of the richest variety of bird species on earth, hosting about 12.5 percent of known species of birds. Many of these flora and fauna species are endemic to India. Indian forests and wetlands serve as temporary home to many migrant birds. [edit]Trading

in exotic birds

India was, until 1991, one of the largest exporters of wild birds to international bird markets. Most of the birds traded [11] were parakeets and munias. Most of these birds were exported to countries in Europe and the Middle East. In 1991, India passed a law that banned all trade and trapping of indigenous birds in the country. The passage of the law stopped the legal exports, but illegal trafficking has continued. In 2001, for example, an attempt to smuggle some 10000 wild birds was discovered, and these birds were confiscated at the Mumbai international airport. According to a WWF-India published report, trapping and trading of some 300 species of birds continues in India, representing 25% of known species in the country. Tens of thousands of birds are trapped from the forests of India, and traded every month to serve the demand for bird pets. Another market driver for bird trapping and trade is the segment of Indians who on certain religious occasions, buy birds in captivity and free them as an act of kindness to all living beings of the world. Trappers and traders know of the need for piety in these people, and ensure a reliable supply of wild birds so that they can satisfy their urge to do good. The trappers, a detailed survey and investigation reveals are primarily tribal communities. The trappers lead a life of poverty and migrate over time. Their primary motivation was economics and the need to financially support their [12][13] families. Trapping and transport of trapped birds from India's forests has high injury and losses, as in other parts of the world. For every bird that reaches the market for a sale, many more die. Abrar Ahmed, the WWF-India and TRAFFIC-India ornithologist, suggests the following as potentially effective means [12] of stopping the harm caused by illegal trading of wild birds in India:

Engage the tribal communities in a constructive way. Instead of criminalizing their skills at finding, recognizing, attracting and capturing birds, India should offer them employment to re-apply their skills through scientific management, protection and wildlife preservation. Allow captive and humane breeding of certain species of birds, to satisfy the market demand for pet birds. Better and continuous enforcement to prevent trapping practices, stop trading and end smuggling of wild birds of India through neighboring countries that have not banned trading of wild birds. Education and continued media exposure of the ecological and environmental harm done by wild bird trade, in order to reduce the demand for trapped wild birds as pets.

[edit]Conservation

Forest around Nohkalikai fall inMeghalaya, an eastern state of India

Greater Flamingoes amid forests ofAndhra Pradesh.

The role of forests in the national economy and in ecology was further emphasized in the 1988 National Forest Policy, which focused on ensuring environmental stability, restoring the ecological balance, and preserving the remaining forests. Other objectives of the policy were meeting the need for fuelwood, fodder, and small timber for rural and tribal people while recognizing the need to actively involve local people in the management of forest resources. Also in 1988, the Forest Conservation Act of 1980 was amended to facilitate stricter conservation measures. A new target was to increase the forest cover to 33 percent of India's land area from the then-official estimate of 23 percent. In June 1990, the central government adopted resolutions that combined forest science with social forestry, that is, taking the sociocultural traditions of the local people into. The cumulative area afforested during the 1951-91 period was nearly 179,000 square kilometres. However, despite large-scale tree planting programs, forestry is one arena in which India has actually regressed since independence. Annual fellings at about four times the growth rate are a major cause. Widespread pilfering by villagers for firewood and fodder also represents a major decrement. In addition, the 1988 National Forest Policy noted, the forested area has been shrinking as a result of land cleared for farming and development programs. Between 1990 and 2010, as evidenced by satellite data, India has reversed the deforestation trend. FAO reports India's rate of forest addition has increased in recent years, and as of 2010, it is the third fastest in the world in increasing forest cover. The 2009 Indian national forest policy document emphasizes the need to combine India's effort at forest conservation with sustainable forest management. India defines forest management as one where the economic needs of local communities are not ignored, rather forests are sustained while meeting nation's economic needs and local issues [8] through scientific forestry. Conclusion Forest rejuvenation is occurring in the east Indian states of West Bengal, Orissa and Bihar, as a consequence of community protection and the regulation of access. In a significant departure in the relationship between forests, people and the state, a new meeting point between the Forest Department, and rural communities is facilitating a cooperative management of forest land, called joint forest management. In Orissa, however, community forest management, without support from the state, and in what can be interpreted as a new, subtle form of environmental activism, is likewise showing forest regeneration, notably in areas of derelict Reserved forests.

Where forest management with people's participation has shown to be successful, contributing factors can be identified; forest degradation appears to be a strong motivating factor, particularly when adverse conditions, associated with forest degradation impacts upon local communities, such as lack of biomass, or loss of income generating opportunities, etc.., conversely, for regeneration to occur, there must be sufficient 'ecological potential', notably sal rootstock in the ground. A strong local institution is also a prerequisite for a sustained management and distribution of forest resources. However, in Orissa, where forest protection and management is generated from entirely within the community, institutional instability, lack of legitimacy and support from the state, and an informal management regime may jeopardise community forest management. As a community initiative, however, the success of forest protection and management in Orissa is clear. The regeneration of Shorea robusta is a remarkable achievement. In Budhikhamari, the sal forest was young and dense, where once, not so long ago, it was scrub less than a metre high. Whether the forest will age, will be as much a matter of harvest rate, as the effectiveness of future management and protection, which currently appears precarious. Certainly Budhikhamari forest presently yields sufficient biomass for all the village subsistence needs, and offers an increased potential for generating income from the marketing of sal leaf plates. Similar cases of regeneration are also noted at Chaatipur, Bajrakot and Khairpally, though perhaps the motives for protection in these three villages are more market-driven, than the need for biomass. Nonetheless, all groups appeared to experience considerable challenges in their efforts to protect 'their' forests, which testify to the overall resolve of these community groups. Should similar efforts of community protection be applied to Maninag, regeneration would be likely, given the high biological potential of the area. However the context of forest degradation is more complex than the simple figures of deforestation would suggest. What might appear as environmental degradation might also be an integral component to the agricultural economy, by the provision of grazing land.

Objectives

The objectives of Forest Survey of India are:

[3]

1. To prepare State of Forest Report biennially, providing assessment of latest forest cover in the country and monitoring changes in these. 2. To conduct inventory in forest and non-forest areas and develop database on forest tree resources. 3. To prepare thematic maps on 1:50,000 scale, using aerial photographs. 4. To function as a nodal agency for collection, compilation, storage and dissemination of spatial database on forest resources.

You might also like

- Environmental Science SyllabusDocument4 pagesEnvironmental Science Syllabusyabaeve100% (5)

- Krushi Parasharaha 1Document13 pagesKrushi Parasharaha 1Sagar Sharma0% (1)

- Zamboanga City Animal Rehab Center Promotes Sustainable ArchitectureDocument31 pagesZamboanga City Animal Rehab Center Promotes Sustainable Architecturetyrion lanisterNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Powerpoint STSDocument24 pagesBiodiversity Powerpoint STSsean go100% (2)

- Conservation of Biodiversity: BiologyDocument28 pagesConservation of Biodiversity: BiologyGissele Abolucion100% (1)

- ENVISCI - 6 Ecological PrinciplesDocument38 pagesENVISCI - 6 Ecological PrinciplesAgatha Diane Honrade100% (1)

- Handbook of Bird Biology, Second EditionDocument3 pagesHandbook of Bird Biology, Second EditionMuddassar Zafar100% (1)

- Types of Forests in IndiaDocument4 pagesTypes of Forests in IndiaAditya Thakur100% (1)

- Rivers of India PDFDocument16 pagesRivers of India PDFSugundan MurugesanNo ratings yet

- Vastu Shastra New Concept in ArchitecturDocument15 pagesVastu Shastra New Concept in ArchitecturVigiNo ratings yet

- Sources and Approaches to the Study of Modern Indian HistoryDocument36 pagesSources and Approaches to the Study of Modern Indian HistorySounak Biswas100% (1)

- Mughal Architecture of IndiaDocument13 pagesMughal Architecture of IndiaRishi UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Vastu Shastra PDFDocument9 pagesVastu Shastra PDFVikas R GowdaNo ratings yet

- Natural Vegetation of IndiaDocument7 pagesNatural Vegetation of IndiaVarun ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Govt Job Prediction by Date of Birth and Time - Govt Job YogDocument5 pagesGovt Job Prediction by Date of Birth and Time - Govt Job YogDhriti GamingNo ratings yet

- Investment On Akshay TritiyaDocument8 pagesInvestment On Akshay Tritiyasandeep SahniNo ratings yet

- Biography: Aryabhata (IAST: Āryabhaṭa; Sanskrit: आयरभटः) (476-550 CE) was the first in theDocument7 pagesBiography: Aryabhata (IAST: Āryabhaṭa; Sanskrit: आयरभटः) (476-550 CE) was the first in theshabaan786No ratings yet

- Dr. Nagendra SinghDocument3 pagesDr. Nagendra SinghNeelima MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Horasara of Prithuyasas Son of VarahamihiraDocument117 pagesHorasara of Prithuyasas Son of Varahamihirapramodc220% (1)

- AryabhataDocument9 pagesAryabhatamallareddy304100% (1)

- Vastu Shastra: Ancient Indian Science of Architecture for Health, Prosperity and HappinessDocument2 pagesVastu Shastra: Ancient Indian Science of Architecture for Health, Prosperity and HappinessvastudeepNo ratings yet

- PrelimsDocument60 pagesPrelimsRV QuizCorpNo ratings yet

- X - Geography Ch-1 - Notes On Soil ResourceDocument3 pagesX - Geography Ch-1 - Notes On Soil ResourcekushalcmevadaNo ratings yet

- Six Types of Soil Testing Vastu MethodsDocument7 pagesSix Types of Soil Testing Vastu MethodslipavikaNo ratings yet

- Lord SubramanyamDocument5 pagesLord SubramanyamSriram BharatNo ratings yet

- Bhava Chandrika Missing Links of Hindu AstrologyDocument32 pagesBhava Chandrika Missing Links of Hindu AstrologyAdya TripathiNo ratings yet

- Religious Reform Movements in India Between 8th-16th CenturiesDocument4 pagesReligious Reform Movements in India Between 8th-16th CenturiesLokesha H HlmgNo ratings yet

- 11 Chapter 3Document25 pages11 Chapter 3poojaNo ratings yet

- Glimpse Vedic Literature Fundamental TextsDocument3 pagesGlimpse Vedic Literature Fundamental TextsSanskari YuviNo ratings yet

- Part of SpeechDocument20 pagesPart of SpeechAyu Putri Aryati100% (1)

- Geography of India - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocument16 pagesGeography of India - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFSaurabh KalkarNo ratings yet

- VarahamihiraDocument6 pagesVarahamihiraSTAR GROUPS100% (1)

- Panch Tattva - The five classical elements in SikhismDocument6 pagesPanch Tattva - The five classical elements in SikhismManish SankrityayanNo ratings yet

- How To Find Ishta DevataDocument6 pagesHow To Find Ishta DevatakalyansundaramvNo ratings yet

- Teaching Skills and Shad Darshanas: Reflecting On Prominent Micro Teaching Skills Apropos Pramanas in Epistemology of Indian PhilosophyDocument17 pagesTeaching Skills and Shad Darshanas: Reflecting On Prominent Micro Teaching Skills Apropos Pramanas in Epistemology of Indian PhilosophyAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- SEO-Optimized Title for Puranic Dashavatara DocumentDocument8 pagesSEO-Optimized Title for Puranic Dashavatara DocumentRonak jiNo ratings yet

- New Architecture and Urbanism: International ConferenceDocument22 pagesNew Architecture and Urbanism: International ConferencesatyanarayaNo ratings yet

- Narayana DasaDocument2 pagesNarayana DasaEd AmNo ratings yet

- Vedic Astrology Houses, Signs and PlanetsDocument3 pagesVedic Astrology Houses, Signs and PlanetsRaphael FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Letter Writing Tips and ExamplesDocument12 pagesLetter Writing Tips and ExamplesMlivia Dcruze50% (2)

- Physics E401 Magnetic Fields and Magnetic Force Analysis/ConclusionDocument3 pagesPhysics E401 Magnetic Fields and Magnetic Force Analysis/ConclusionSuperbiamperum67% (3)

- Vastu Shastra: Indian Feng ShuiDocument4 pagesVastu Shastra: Indian Feng ShuiSouradeep PaulNo ratings yet

- Kalpalataa - 1: Éï Aéhéåzééré LéqéèDocument24 pagesKalpalataa - 1: Éï Aéhéåzééré LéqéèPrakash Chandra Tripathy100% (1)

- Environmental Considerations in Vaastu Culture For Residential Building OrientationDocument8 pagesEnvironmental Considerations in Vaastu Culture For Residential Building Orientationpreetharajamma6025No ratings yet

- Prayers Addressed To Lord Anjaneya in Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil and TeluguDocument171 pagesPrayers Addressed To Lord Anjaneya in Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil and Telugudhawal gargNo ratings yet

- Panchabootha BooKDocument15 pagesPanchabootha BooKrkloganathanNo ratings yet

- 12 Legal Studies Lpy 2018Document15 pages12 Legal Studies Lpy 2018Milind YadavNo ratings yet

- The Principles of NamingDocument10 pagesThe Principles of NamingmalarvkNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law-I: 3year LLB CourseDocument3 pagesConstitutional Law-I: 3year LLB Courseabhilasha mehtaNo ratings yet

- Vargavimshopakam (Vimshopaka Bala)Document2 pagesVargavimshopakam (Vimshopaka Bala)Pt AkaashNo ratings yet

- Letter Writing (6 Marks)Document32 pagesLetter Writing (6 Marks)PRIYANSHUNo ratings yet

- Brahmacharya - 1. Swami Vivekananda PDFDocument9 pagesBrahmacharya - 1. Swami Vivekananda PDFkumar samyappanNo ratings yet

- Engineering Philosophy of Ancient IndiaDocument36 pagesEngineering Philosophy of Ancient IndiaAshok NeneNo ratings yet

- Brahmin - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument8 pagesBrahmin - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaShree Vishnu ShastriNo ratings yet

- Impact of Malavya Panch Mahapurush Yoga On A PersonDocument2 pagesImpact of Malavya Panch Mahapurush Yoga On A PersonVasanthapragash Nadarajha100% (1)

- Hindu TempleDocument15 pagesHindu TempleT Sampath KumaranNo ratings yet

- Profession: Nature of SignDocument5 pagesProfession: Nature of SignmagicalseasNo ratings yet

- Temple Architecture LayoutsDocument13 pagesTemple Architecture LayoutskengerisudhirNo ratings yet

- Graha SamayaDocument2 pagesGraha SamayaSriNo ratings yet

- Ashram ADocument16 pagesAshram AManvendra Shahi100% (1)

- Kannada PDFDocument33 pagesKannada PDFSanju DubsNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit SahakarinDocument59 pagesSanskrit SahakarinAnilkumar Shankarbhat NagarakattiNo ratings yet

- People and the Peepal: Cultural Attitudes to Sacred Trees and Their Conservation in Urban AreasFrom EverandPeople and the Peepal: Cultural Attitudes to Sacred Trees and Their Conservation in Urban AreasNo ratings yet

- Display Raj PatraDocument2 pagesDisplay Raj PatraŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- MCGM PF SlipDocument2 pagesMCGM PF SlipŚáńtőśh Mőkáśhí100% (3)

- Badminton: Cleanliness SloganDocument3 pagesBadminton: Cleanliness SloganŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra Rain Ahawal + 2 PhotosDocument2 pagesMaharashtra Rain Ahawal + 2 PhotosŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Daily tasks and responsibilities of McCafe staffDocument1 pageDaily tasks and responsibilities of McCafe staffŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- At Home + School + PlaygroundDocument1 pageAt Home + School + PlaygroundŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Where Do Roses GrowDocument3 pagesWhere Do Roses GrowŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Corruption's Big Threat to Societal Well-BeingDocument2 pagesCorruption's Big Threat to Societal Well-BeingŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Group 4Document34 pagesGroup 4Śáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- The India of My DreamsDocument1 pageThe India of My DreamsŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Corvus (genus) - Characteristics of Crows and RavensDocument5 pagesCorvus (genus) - Characteristics of Crows and RavensŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Front PageDocument4 pagesFront PageŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- IndiaDocument3 pagesIndiaGanesh KaleNo ratings yet

- 10 Common Plants in EuropeDocument7 pages10 Common Plants in EuropeŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Car Reverse Horn Circuit GuideDocument8 pagesCar Reverse Horn Circuit GuideŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Lec5 6Document35 pagesLec5 6priyasanthakumaranNo ratings yet

- Swami Vivekananda: Bengali: BengaliDocument1 pageSwami Vivekananda: Bengali: BengaliŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Instituteinformation2011 Engg PDFDocument113 pagesInstituteinformation2011 Engg PDFŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Sushant Suresh VajeDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Sushant Suresh VajeŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Water Supply and Sanitation: Railway Advantages: 1. DependableDocument2 pagesWater Supply and Sanitation: Railway Advantages: 1. DependableŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Rohan Dilip Milkhe: Residential & Permanent AddressDocument2 pagesRohan Dilip Milkhe: Residential & Permanent AddressŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- App 27802794462079Document2 pagesApp 27802794462079Śáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Baithe KhelDocument1 pageBaithe KhelŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- No 2-Part2-4 India PDFDocument27 pagesNo 2-Part2-4 India PDFŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Personal ProfileŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

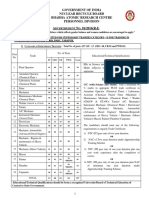

- Government of India Nuclear Recycle Board Bhabha Atomic Research Centre Personnel Division A N - 01/2016 (R-I)Document7 pagesGovernment of India Nuclear Recycle Board Bhabha Atomic Research Centre Personnel Division A N - 01/2016 (R-I)Śáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- The Right Tree in The Right Place For A Resilient FutureDocument33 pagesThe Right Tree in The Right Place For A Resilient FutureJonathan German AlacioNo ratings yet

- %@.jryt@@",,2 : '", $NFTRDocument5 pages%@.jryt@@",,2 : '", $NFTRMathematics KingNo ratings yet

- Key Questions: Chapter 4.3: SuccessionDocument2 pagesKey Questions: Chapter 4.3: SuccessionChizara IdikaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Urbanisation On Species RichnessDocument16 pagesEffects of Urbanisation On Species RichnessPrashanth GuvvalaNo ratings yet

- CasebookDocument6 pagesCasebookapi-451310909No ratings yet

- Philippine HitoDocument13 pagesPhilippine Hitogriffin01No ratings yet

- S Y B Tech (Mechanical Engg) SyllabusDocument30 pagesS Y B Tech (Mechanical Engg) SyllabusBhavesh JainNo ratings yet

- Evs AssignmentDocument5 pagesEvs AssignmentRohit YadavNo ratings yet

- National Conservation StrategyDocument53 pagesNational Conservation StrategyAS Consultancy & TrainersNo ratings yet

- Qila SaifullahDocument57 pagesQila SaifullahMohammad Yahya Musakhel100% (2)

- Conservation Area Management PlanDocument111 pagesConservation Area Management PlanAnonymous 6upsAg3ouNo ratings yet

- Uganda Wildlife Act, 2019Document102 pagesUganda Wildlife Act, 2019African Centre for Media Excellence100% (2)

- Identifying species threat hotspots from global supply chainsDocument5 pagesIdentifying species threat hotspots from global supply chainsJuan Pablo DelgadoNo ratings yet

- JICA KNOWLEDGE CO-CREATION PROGRAM GROUP REGION FOCUSDocument359 pagesJICA KNOWLEDGE CO-CREATION PROGRAM GROUP REGION FOCUSRusmadi Adi PutraNo ratings yet

- Yamuna Biodiversity Park: Virtual Visit ToDocument7 pagesYamuna Biodiversity Park: Virtual Visit ToGovind Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- DelwDocument251 pagesDelwPhuongLoan100% (1)

- Working For The Great Outdoor - 1Document94 pagesWorking For The Great Outdoor - 1Asad KhalidNo ratings yet

- Book Giant AnteaterDocument93 pagesBook Giant Anteatergameta45100% (1)

- EVS Important Questions With Answers PrintDocument20 pagesEVS Important Questions With Answers PrintBhavya GoelNo ratings yet

- Leal Et Al 2016Document12 pagesLeal Et Al 2016Stephanie Menezes RochaNo ratings yet

- Birds in Europe (SEO)Document400 pagesBirds in Europe (SEO)Curriquito100% (2)

- Revisiting Learnings and Envisioning Philippine Mangroves in 2030 Salmo Et Al. 2021Document188 pagesRevisiting Learnings and Envisioning Philippine Mangroves in 2030 Salmo Et Al. 2021Maam Katryn TanNo ratings yet

- Welcome To CIFOR Updated 2014Document55 pagesWelcome To CIFOR Updated 2014Muhamad RismanNo ratings yet

- Từ vựng chủ đề Động vật hoang dãDocument3 pagesTừ vựng chủ đề Động vật hoang dãPhuong MaiNo ratings yet