Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Civil-Military Integration and Chinese Military Modernization

Uploaded by

mbahmumiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Civil-Military Integration and Chinese Military Modernization

Uploaded by

mbahmumiCopyright:

Available Formats

Asia-Pacific Security Studies

Civil-Milit ary Integration and Chinese Milit ary Modernization

Asia-Pacif Asia-Pacif ic Center for for Security Studies Volume Volume 3 - Number 9, December 2004

Key Findings

China has long been aware of the potential benefits of civil-military integration (CMI) in helping to overcome technological shortcomings and other problems plaguing its militaryindustrial complex. Beijing especially sees CMI as advancing its long-term aim of achieving self-sufficiency in developing and producing advanced arms.

Mr. Richard A. Bitzinger is a Associate Research Professor with the AsiaPacific Center for Security Studies. His work focuses mainly on military and defense issues relating to the Asia-Pacific region. His most recent APCSS publication is Challenges to Transforming AsianPacific Militaries (October 2004). He is also the author of Towards a Brave New Arms Industry? (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Chinese attempts at CMI in the 1980s and early 1990s were basically an effort to convert military factories over to civilian production. These efforts were only modestly successful, however, and they did little to transfer innovative commercial technologies to military uses. Since the mid-1990s, China has pursued an active strategy of dual-use technology development and commercial-to-military spin-on, particularly in the areas of microelectronics, space systems, new materials, propulsion, missiles, computer-aided manufacturing, and information technologies (IT). Certain sectors in China's military-industrial complex appear to be benefiting from this dual-use CMI approach, especially shipbuilding and aerospace (missiles and satellites). The military has also benefited from leveraging developments in China's booming commercial IT industry, and consequently it has greatly expanded and improved its capacities for command, control and communications, information-processing, and information warfare.

CMI in China is still quite limited, however, and there is little evidence of significant dual-use technology development and commercial-to-military spin-on in other defense sectors. There still exist many gaps in China's science and technology base, and China's commercial high-tech sector is still quite weak. Given the considerable promise and potential of CMI, however, China will likely continue to promote dual-use technology development and spin-on as a means of promoting the country's military buildup. It will be difficult if not impossible for the United States and other Western powers to restrict dual-use technology exports to China, but they could perhaps take steps to offset their effects.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, U.S. Pacific Command, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Civil-Military Integration and Chinese Military Modernization

Introduction

Civil-military integration (CMI) is the process of combining the defense and civilian industrial bases so that common technologies, manufacturing processes and equipment, personnel, and facilities can be used to meet both defense and commercial needs. According to the U.S. Congressional Office of Technology Assessment, CMI includes: cooperation between government and commercial facilities in research and development (R&D), manufacturing, and/or maintenance operations; combined production of similar military and commercial items, including components and subsystems, side by side on a single production line or within a single firm or facility, and use of commercial off-the-shelf items directly within military systems. CMI can occur on three levels: facility, firm, and sector. Facilities can share personnel, equipment, and materials, and even manufacture defense and civilian goods side-by-side. Firm-level integration involves separate production lines but the joint military-civilian use of corporate resources (management, labor, and equipment). Finally, integrated industrial sectors (such as aerospace or shipbuilding) can draw from a common pool of research and development activities, technologies, and production processes. There are many potential benefits of CMI to military modernization efforts. Adapting already available commercial technologies to meeting military needs can save money, shorten development and production cycles, and reduce risks in weapons development. CMI can also improve the quality of military equipment and contribute to more efficient production and acquisition of military systems. Above all, CMI permits arms industries and militaries to leverage critical technological advances in sectors where the civilian side has clearly taken the lead in innovation, particularly information technologies (IT), such as communications, computing, and microelectronics. In this regard, the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) has been particularly influenced by the emerging IT-based revolution in military affairs, and it sees considerable potential for force multipliers in such areas as information warfare, digitization of the battlefield, and networked systems. China, like many countries, is keenly aware of the potential benefits of CMI in reducing the costs and risks of weapons development and production, and in accelerating the process of military modernization. Additionally, however, the Chinese military sees CMI as advancing its long-term objective of greater self-sufficiency in arms procurement, by enabling the PLA "to source more of its critical and sensitive technologies domestically" and subsequently reduce its dependencies upon foreign suppliers for its most advanced weapons. For China, therefore, CMI is basically a new wrinkle on the classic techno-nationalist development strategy of a joint government-industry-military effort to acquire, nurture, indigenize, and diffuse critical dual-use technologies deemed essential to national security and defense. China, therefore, has a considerable stake in making CMI work.

technology base is perhaps 20 years behind the West in several critical areas, including aeronautics, propulsion (such as jet engines), microelectronics, computers, avionics, sensors and seekers, electronic warfare, and advanced materials. The arms industry has traditionally been poor when it comes to quality control and systems integration, and burdened by too many workers too much productive capability, and too many managers afraid to take risks and to embrace market forces. As a result, arms production in China has largely been inefficient, wasteful, and unprofitable. Finally, China's defense industry has typically been isolated from the rest of the country's industrial base, limiting its access to innovation and breakthroughs found in other sectors of the national economy.

China's Defense Industry and CMI, Early 1980s to the Mid-1990s: Defense Conversion

The Chinese defense industry's first attempts at civil-military integration ran from roughly the early 1980s to the mid-1990s and were basically an effort to rectify its acute economic, structural, and organizational problems through a concerted attempt to convert military factories over to the manufacture of civilian products. In particular, commercial production was seen as a means of absorbing excess capacity and manpower in the arms-producing sector, providing defense enterprises with additional sources of revenues to compensate for their under-performing military product lines, and encouraging their directors and managers to bring their enterprises more in line with market forces. This strategy was officially embodied in Deng Xiaoping's so-called "Sixteen Character" slogan, which called for "combining the military and civil, combining peace and war, giving priority to military products, and making the civil support the military." With Beijing's enthusiastic blessing, therefore, the defense industry branched out into a broad array of civilian manufacturing during the 1980s and 1990s. China's aviation industry, for example, established a number of commercial joint ventures with Western aircraft companies. The McDonnell Douglas Corporation set up a production line in Shanghai to build MD-82 and MD-90 passenger jets. Boeing, the European Airbus consortium, Sikorsky Helicopter, Pratt & Whitney (a manufacturer of jet engines), and Bombardier of Canada all established facilities at various China aircraft factories to produce subassemblies and parts for Western civil aircraft. Beginning in the 1980s, Chinese shipyards successfully converted much of their production to more profitable civilian products, such as bulk carriers and general cargo ships. China's missile industry entered the lucrative satellite-launching business, with its series of Long March space-launch vehicles. Additionally, many defense enterprises became engaged in commercial ventures far outside of their traditional economic activities. Ordnance factories assembled motorcycles, aircraft companies built mini-cars and buses, and missile facilities put together refrigerators, television sets, and even corrugated boxes. By the mid-1990s, 70 percent of all taxicabs, twenty percent of all cameras, and two-thirds of all motorcycles produced in China came out of former weapons factories. By the late 1990s, 80 to 90 percent of the value of defense industry output was estimated to be nonmilitary. Very little of this earlier conversion effort actually aided the Chinese military-industrial complex, however. For one thing, defense conversion has been no guarantee of financial success, and many former weapons factories have actually lost money on civilian production. In particular, many failed to create reliable, "main-stay" product lines or develop a more consumer-savvy attitude when it came to price, quality, and adding new features. More important, defense conversion did little to benefit China's defense industry in terms of acquiring and diffusing potentially useful commercial technologies to the military sector. The concern that con2

Background to the Chinese Military-Industrial Complex

China possesses one of the oldest, largest, and most diversified militaryindustrial complexes in the developing world. It is one of the few countries in the newly industrialized world to produce a full range of military equipment, from small arms to armored vehicles to fighter aircraft to warships and submarines, in addition to nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles. At the same time, the state-owned military-industrial complex has long suffered from a number of weaknesses and shortcomings. China's defense

Civil-Military Integration and Chinese Military Modernization

version meant a process of "swords into plowshares - and better swords" was largely unfounded. If anything, spin-off - that is, the transfer of military technologies to civilian applications (such as in the development of China's space-launch business, which was initially based on the commercialization of its intercontinental ballistic missile systems) - was more important during this period than civilian-to-military spin-on. At the same time, the opportunities for the direct spin-on of civilian technologies to military production remained limited. In the aviation industry, for example, while the Chinese acquired a number of advanced numerically controlled machine tools, for use in commercial aircraft production, end-user restrictions kept these from being diverted to military use. With regard to the shipbuilding industry, even as late as the mid1990s commercial programs had little impact on improving China's ability to produce modern warships or to develop advanced naval technologies. The shipbuilding industry's low technology base, while sufficient for building cargo ships, offered little value-added to the design and construction of warships. This is not to say that some efforts at dual-use technology development did not take place during this period. In fact, a critical science and technology development effort, the so-called 863 Program, was launched in the mid-1980s; the 863 Program was a long-term initiative to expand and advance China's high-technology base in a number of areas, many of which had potential military applications, including aerospace, lasers, opto-electronics, semiconductors, and new materials. The 863 Program, however, was essentially a basic and applied research activity, and initially it was not set up (or funded) in order to promote and diffuse these technologies for practical - and particularly military - uses. At best, therefore, efforts at civil-military integration during this period only indirectly aided Chinese weapons development and production, to the extent that the military-industrial complex benefited from overall economic growth. In some cases, defense conversion did help to reduce overhead costs and generate new sources of income to underwrite new arms production. In general, however, there were few linkages between military and civilian production and, in particular, very few efforts to develop dual-use technologies or to apply innovative civilian technologies to military uses. industrial developments in the area of defense-related electronics. Under the Tenth Five Year Plan (2001-2005), many technology breakthroughs generated under the 863 S&T program were finally slated for development and industrialization. Defense enterprises have formed partnerships with Chinese universities and civilian research institutes to establish technology incubators and undertake cooperative R&D on dual-use technologies. Additionally, foreign high-tech firms wishing to invest in China have been pressured to set up joint R&D centers and to transfer more technology to China. These efforts at exploiting dual-use technologies have apparently paid dividends in at least a few defense sectors. China's military shipbuilding, for example, appears to have particularly benefited from CMI efforts over the past decade. Following an initial period of basically low-end commercial shipbuilding - such as bulk carriers and container ships - China's shipyards have since the mid-1990s progressed toward more sophisticated ship design and construction work. In particular, moving into commercial shipbuilding began to bear considerable fruit beginning in the late 1990s, as Chinese shipyards modernized and expanded operations, building huge new dry-docks, acquiring heavy-lift cranes and computerized cutting and welding tools, and more than doubling their shipbuilding capacity. At the same time, Chinese shipbuilders entered into a number of technical cooperation agreements and joint ventures with shipbuilding firms in Japan, South Korea, Germany, and other countries, which gave them access to advanced ship designs and manufacturing technologies in particular, computer-assisted design and manufacturing, modular construction techniques, advanced ship propulsion systems, and numerically controlled processing and testing equipment. As a result, military shipbuilding programs collocated at Chinese shipyards have been able to leverage these considerable infrastructure and software improvements when it comes to design, development, and construction. This in turn has permitted a significant expansion in naval ship construction since the turn of the century, and since 2000, China has launched at least six new diesel-powered submarines, three destroyers, and four frigates, with eight more warships under construction; this is nearly double the rate of naval ship construction during the 1990s. Moreover, the quality and capabilities of Chinese warships have also apparently improved. In 2001, for example, China began work on the first in a new class of domestically developed, 9,000-ton guided-missile destroyer, the Type 052B, equipped with a long-range air-defense missile system and incorporating low-observable features in its design. A further refinement on this class, outfitted with a rudimentary Aegis-type phasedarray radar, is the Type-052C destroyer, first launched in 2003. China is also currently producing the Song-class diesel-electric submarine, the first Chinese submarine to have a skewed propeller for improved quieting and capable of carrying an encapsulated antiship cruise missile that can be launched underwater. Even more important, the PLA has clearly benefited from piggybacking on the development and growth of the country's commercial IT industry. The PLA is working hard to expand and improve its capacities for command, control and communications, informationprocessing, and information warfare, and it has been able to enlist many local IT firms in support of its efforts. These include Huawei Technologies (which manufactures switches and routers for communications networks), Zhongxing Telecom (ZTE, mobile and fiberoptic networks), Julong (switchboards), and Legend and Beijing Founder (computers). Many of these companies have close ties to China's military-industrial complex, and some, such as Huawei, Julong, and Legend, were founded by former PLA officers. Consequently, the PLA has developed its own separate military communications network, utilizing fiber-optic cable, cellular and wireless systems, microwave relays, and long-range high frequency radios, as well as computer local area networks. Two other defense sectors are worth noting when it comes to achieving some success in civil-military integration. First, China's satellite business 3

China's Defense Industry and CMI, Mid-1990s to the Present: Exploitation of Dual-Use Technologies

China's approach to civil-military integration began to change around the mid-1990s, and it entailed a crucial shift in policy, from conversion (i.e., switching military factories over to civilian use) to the promotion of integrated dual-use industrial systems capable of developing and manufacturing both defense and military goods. This new strategy was embodied and made a priority in the defense industry's five-year plan for 20012005, which emphasized the dual importance of both the transfer of military technologies to commercial use and the transfer of commercial technologies to military use, and which therefore called for the Chinese arms industry to not only to develop dual-use technologies but to actively promote joint civil-military technology cooperation. Consequently, the spinon of advanced commercial technologies both to the Chinese militaryindustrial complex and in support of the overall modernization of the PLA was made explicit policy. The key areas of China's new focus on dual-use technology development and subsequent spin-on include microelectronics, space systems, new materials (such as composites and alloys), propulsion, missiles, computer-aided manufacturing, and particularly information technologies. Over the past decade, Beijing has worked hard both to encourage further domestic development and growth in these sectors and to expand linkages and collaboration between China's military-industrial complex and civilian high-technology sectors. In 2002, for example, the Chinese government created a new enterprise group, the China Electronics Technology Corporation, to promote national technological and

Civil-Military Integration and Chinese Military Modernization

has entailed the considerable development and application of dual-use civilian technologies. Chinese telecommunications satellites are basically commercial in nature, as is China's rudimentary Beidou navigation satellite system, but both serve military purposes as well. In particular, recent Chinese successes in launching earth observation satellites - such as the Ziyuan-1 and Ziyuan-2 - have critical military applications in providing near-real time - and increasingly high-resolution - imagery intelligence. In addition, many of the technologies being developed for commercial reconnaissance satellites, such as charge-coupled device cameras, multispectral scanners, and synthetic aperture radar imagers, have obvious spin-on potential for military systems. Secondly, China's small but growing helicopter industry has always been dual-use in execution, such as the licensed-production of the French AS365 Dauphin 2 (used by the PLA Navy for antisubmarine warfare, for example), and the more recent development of the indigenous Z-10 utility helicopter, which includes an armed attack version. microprocessor chips, must be imported.. Finally, many of the country's high-technology incubators are still very much in their nascent stage, and Beijing continues to spend relatively little on high technology compared to the United States and the rest of the West. Moreover, much of China's high-technology R&D and industrial base is still foreign-controlled, either through foreign-owned companies or joint ventures. Foreigners own virtually all of China's high-technology intellectual property and most of its manufacturing capacity (such as semiconductor plants), and as such, 85 percent of China's high-tech exports come from foreign-owned or joint ventures operations. In addition, many foreign-established so-called R&D centers are actually geared more toward training and education than joint S&T development. Overall, therefore, civil-military integration in China is still very much in its early stages, and both civilian and military authorities have yet to formulate a specific strategy for more effectively exploiting CMI. As one consequence, therefore, the R&D of defense-specific technologies, as well as the importation of such technologies, continues to be crucial in the modernization of the country's military-industrial complex and in the development of next-generation weapons systems. Nevertheless, CMI still has considerable potential to revolutionize the way militaries develop and produced defense-critical systems. It holds particular promise in the area of adapting commercial information technologies - know-how increasingly seen as essential to transforming armed forces for next-generation warfare - to military purposes. For these reasons, therefore, China is likely to continue to search for ways to promote dual-use technology development and exploit commercial-tomilitary spin-on in support of its military modernization efforts. Beijing's efforts to utilize dual-use technologies for military modernization have considerable implications for the United States and its allies in the Asia-Pacific. China is in the midst of an unprecedented military buildup that could greatly upset the regional security calculus. The United States has an obvious interest in retarding this effort - hence, its continued opposition to lifting the Western ban on arms sales to China. Dual-use technology exports are much harder to control, however, particularly since such transfers are usually commercial and therefore seen as benign and beneficial to both seller and buyer alike. In addition, many of these technologies are already widely diffused throughout the world, and it would be difficult and even impractical to try to restrict their sales. Consequently, while the United States may not be able to halt the process of Chinese civil-military integration and dual-use technology exploitation, it can, by better understanding the strengths and weaknesses of such an approach, perhaps take steps to offset their effects. In any event, the proliferation of military technologies is no longer simply a matter of immediate end-use but of all of its potential uses.

Conclusions

Despite these achievements, Chinese civil-military integration efforts particularly when it comes to commercial-to-military spin-on have remained limited. There is little evidence so far of any significant civilmilitary integration in other sectors of the Chinese defense industry, particularly the aviation industry where one might expect CMI to be a naturally occurring phenomenon. Commercial and military aircraft manufacturing in China is still carried out not only (and perhaps unavoidably) on separate production lines, but also in separate facilities and often in separate enterprises, with little apparent communication and crossover between these compartmentalized operations. Moreover, with the exception of helicopters (and possibly transport aircraft), the technological overlap between civil aviation and military aircraft (particularly fighter aircraft) is small and not very conducive to CMI. As such, there are few opportunities to share personnel, production processes, and materials, and perhaps even fewer prospects for joint R&D or collocated production. Likewise, China's overall record of indigenous high-technology development and innovation has been mixed, further limiting opportunities for CMI. There still exist many gaps and weaknesses in China's S&T base, and very little indigenous design and manufacturing actually takes place in much of China's high-technology sectors. Rather, high-tech production is still oriented toward the fabrication of relatively mature consumer or commodity goods, such as DVD players or semiconductors, built according to original equipment manufacturer (OEM) specifications. In addition, China still lacks sufficient numbers of skilled designers engineers, scientists, and technicians in crucial high-technology sectors, particularly IT, and so most high-end items, such as

The Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS) is a regional study, conference, and research center established in Honolulu on September 4, 1995. complementing PACOM's theater security cooperation strategy of maintaining positive security relationships with nations in the region. The APCSS mission is to enhance cooperation and build relationships through mutual understanding and study of comprehensive security issues among military and civilian representatives of the United States and other Asia-Pacific nations. The Asia-Pacific Security Studies series contributes to the APCSS mission to enhance the region's security discourse. The general editor of the series is Lt. Gen. (Ret.) H.C. Stackpole, President of the APCSS.

Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies

2058 Maluhia Road Honolulu, Hawaii 96815-1949 (808) 971-8900 fax: (808) 971-8999

www.apcss.org 4

You might also like

- Civil-MilitaryIntegratio N 111019 PDFDocument4 pagesCivil-MilitaryIntegratio N 111019 PDFAlanSebastianoNo ratings yet

- Beraud-Sudreau and Nouwens - 2019 - Weighing Giants - Taking Stock of The Expansion of Chinas Defense IndustryDocument28 pagesBeraud-Sudreau and Nouwens - 2019 - Weighing Giants - Taking Stock of The Expansion of Chinas Defense IndustryMartín AlbertoNo ratings yet

- 1AC - AI Logistics (v3)Document40 pages1AC - AI Logistics (v3)noNo ratings yet

- Arms Production EconomicsDocument17 pagesArms Production EconomicsradiccciNo ratings yet

- Russian Military IndustryDocument3 pagesRussian Military IndustryEXTREME1987No ratings yet

- National Security Vol 2 Issue 2 Essay JpsinghDocument12 pagesNational Security Vol 2 Issue 2 Essay JpsinghME20M015 Jaspreet SinghNo ratings yet

- Newspapers' EssayDocument3 pagesNewspapers' EssayMajid KhanNo ratings yet

- Kania ChineseMilitaryInnovation 2019Document54 pagesKania ChineseMilitaryInnovation 2019Hebert Azevedo SaNo ratings yet

- Practical Engagement: Drawing A Fine Line For U.S.-China TradeDocument18 pagesPractical Engagement: Drawing A Fine Line For U.S.-China TradeWu GuifengNo ratings yet

- Buying Military Transformation: Technological Innovation and the Defense IndustryFrom EverandBuying Military Transformation: Technological Innovation and the Defense IndustryNo ratings yet

- Sector DA - ABDocument151 pagesSector DA - ABbojangleschickenNo ratings yet

- China Civil-Military IntegrationDocument7 pagesChina Civil-Military IntegrationLibrairie LivressenceNo ratings yet

- Indigenization Problems in Defence SectorDocument7 pagesIndigenization Problems in Defence SectorAnand KumarNo ratings yet

- China Military BioTech - Read-the-10-08-2019-CB-Issue-in-PDF2Document31 pagesChina Military BioTech - Read-the-10-08-2019-CB-Issue-in-PDF2eden CoveNo ratings yet

- Disruptive Military Technologies - An Overview - Part IIIDocument6 pagesDisruptive Military Technologies - An Overview - Part IIILt Gen (Dr) R S PanwarNo ratings yet

- Is War Necessary For Economic GrowthDocument35 pagesIs War Necessary For Economic Growthfx_ww2001No ratings yet

- Business Is War 1993Document12 pagesBusiness Is War 1993FraumannNo ratings yet

- Clean Copy - Defence Production Policy (r05072018 Email On 23.08.2018) .OutputDocument35 pagesClean Copy - Defence Production Policy (r05072018 Email On 23.08.2018) .OutputYash PurandareNo ratings yet

- SCSP Drone Paper Hinote RyanDocument26 pagesSCSP Drone Paper Hinote RyanJoshNo ratings yet

- EAGLEN - POLLAK Us Military Technological Supremacy Under Threat - 172916742245 PDFDocument24 pagesEAGLEN - POLLAK Us Military Technological Supremacy Under Threat - 172916742245 PDFFabricio PadilhaNo ratings yet

- Arms and Innovation: Entrepreneurship and Alliances in the Twenty-First Century Defense IndustryFrom EverandArms and Innovation: Entrepreneurship and Alliances in the Twenty-First Century Defense IndustryNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2214914723000557 MainDocument17 pages1 s2.0 S2214914723000557 MainAris NasNo ratings yet

- Defense Production, Technological Bases, and Acquisition of EquipmentDocument11 pagesDefense Production, Technological Bases, and Acquisition of EquipmentKeane RazielNo ratings yet

- Asbfy23dmibreport (E)Document37 pagesAsbfy23dmibreport (E)debrah heatonNo ratings yet

- Day 34 Q 4critically Assess The Performance of Indias Defence PSUsDocument3 pagesDay 34 Q 4critically Assess The Performance of Indias Defence PSUsmohammed yunusNo ratings yet

- Fortifying China: The Struggle to Build a Modern Defense EconomyFrom EverandFortifying China: The Struggle to Build a Modern Defense EconomyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Year of The Industrial BaseDocument4 pagesThe Year of The Industrial BaseWaqas Bin Younus AwanNo ratings yet

- Kelkar PDFDocument58 pagesKelkar PDFpavnitkiran02No ratings yet

- Civilianmilitaryco-Operation ResearchPolicyDocument17 pagesCivilianmilitaryco-Operation ResearchPolicyTejas PoojaryNo ratings yet

- Military Technology: Overcoming the Triple-Trap with Single ReformDocument11 pagesMilitary Technology: Overcoming the Triple-Trap with Single ReformAnshul SheoranNo ratings yet

- Transformation or Stagnation The South African Defence Industry in The Early 21st CenturyDocument21 pagesTransformation or Stagnation The South African Defence Industry in The Early 21st Centurygraeme plintNo ratings yet

- Technology Perspective & Capability Roadmap 2013 (India)Document45 pagesTechnology Perspective & Capability Roadmap 2013 (India)Terminal XNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Defence Purchasing & Supply ManagementDocument11 pagesAssignment: Defence Purchasing & Supply ManagementAnil Kumar Motreddy100% (1)

- Horses Nails and Messages Three Defense Industries of The Ukraine WarDocument19 pagesHorses Nails and Messages Three Defense Industries of The Ukraine WarYadira GarayNo ratings yet

- Marcus - Military Utility - A Proposed Concept To Support Decision Making (2015)Document22 pagesMarcus - Military Utility - A Proposed Concept To Support Decision Making (2015)opedroestebanNo ratings yet

- Sejarah Hubungan Bilateral Indonesia-SingapuraDocument19 pagesSejarah Hubungan Bilateral Indonesia-SingapuraHaryo PrasodjoNo ratings yet

- Paper 36: Changing Times? India's Defence Industry in The 21 CenturyDocument47 pagesPaper 36: Changing Times? India's Defence Industry in The 21 Centurymnvr35No ratings yet

- Working Capital Management in India's Defence IndustryDocument72 pagesWorking Capital Management in India's Defence IndustrySathyanarayana SrsNo ratings yet

- South African Defence Industry Turns Around After Painful RestructuringDocument4 pagesSouth African Defence Industry Turns Around After Painful Restructuringgraeme plintNo ratings yet

- Special Operations Technology 2022Document22 pagesSpecial Operations Technology 2022PunkNo ratings yet

- Defence Industrial Strategy 2023Document78 pagesDefence Industrial Strategy 2023inteligenciachatgpt23No ratings yet

- Forging China's Military Might: A New Framework for Assessing InnovationFrom EverandForging China's Military Might: A New Framework for Assessing InnovationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Zheng LeveragingInternet WEBDocument52 pagesZheng LeveragingInternet WEBdaliborNo ratings yet

- The Global Arms Industry in 2030 (And Beyond) The Global Arms Industry in 2030 (And Beyond)Document52 pagesThe Global Arms Industry in 2030 (And Beyond) The Global Arms Industry in 2030 (And Beyond)Wisnu AjiNo ratings yet

- Commander's Corner: March 2010Document21 pagesCommander's Corner: March 2010tordo222100% (1)

- China's Tech Investments Enable Strategic Competitor Access to US InnovationDocument48 pagesChina's Tech Investments Enable Strategic Competitor Access to US InnovationgabrinaNo ratings yet

- Emerging Tech's Impact on Military CapabilityDocument16 pagesEmerging Tech's Impact on Military CapabilityDilawar RizwanNo ratings yet

- US Military Technological Supremacy Under ThreatDocument24 pagesUS Military Technological Supremacy Under ThreatAmerican Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- 48 Strategic Capacity Planning in The Aerospace IndustryDocument8 pages48 Strategic Capacity Planning in The Aerospace Industrybushra asad khanNo ratings yet

- The Place of The Defense Industry in National Systems of InnovationDocument233 pagesThe Place of The Defense Industry in National Systems of InnovationMuhammed YiğitNo ratings yet

- 2008.10.15 Defense Industrial Base PDFDocument108 pages2008.10.15 Defense Industrial Base PDFJohnnyquest911No ratings yet

- China Military Power Report 2019Document136 pagesChina Military Power Report 2019DoctorNo ratings yet

- Origin & Nature of The US Mil-Ind Complex (Vulcan) (2014)Document35 pagesOrigin & Nature of The US Mil-Ind Complex (Vulcan) (2014)John AlicNo ratings yet

- A New Era For Chinese Military InnovationChinas First Offset and Future Warfare - September 2018Document19 pagesA New Era For Chinese Military InnovationChinas First Offset and Future Warfare - September 2018Soe Thet MaungNo ratings yet

- Pentagon Report On China Military 2011Document94 pagesPentagon Report On China Military 2011venky2000No ratings yet

- 2011 China ReportDocument94 pages2011 China Reportipd2167No ratings yet

- DoD IACs Briefing on Cyber Security Technical Area TasksDocument65 pagesDoD IACs Briefing on Cyber Security Technical Area Tasksg9753628No ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence Cyberattack and Nuclear Weapons A Dangerous CombinationDocument7 pagesArtificial Intelligence Cyberattack and Nuclear Weapons A Dangerous CombinationgreycompanionNo ratings yet

- 015 DSCFC 21 e Rev. 2 Fin - China's Defence Posture - MartinhoDocument29 pages015 DSCFC 21 e Rev. 2 Fin - China's Defence Posture - MartinhoDorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Weapons Development in China's Military ModernizationDocument43 pagesIndigenous Weapons Development in China's Military ModernizationOpen BriefingNo ratings yet

- China's Military Modernization-Making Steady and Surprising ProgressDocument5 pagesChina's Military Modernization-Making Steady and Surprising ProgressmbahmumiNo ratings yet

- China's Military Modernization On Land, Sea, and AirDocument6 pagesChina's Military Modernization On Land, Sea, and AirmbahmumiNo ratings yet

- China Naval Modernization-Implications For US NavyDocument115 pagesChina Naval Modernization-Implications For US NavymbahmumiNo ratings yet

- Javascript The Web Warrior Series 6Th Edition Vodnik Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument31 pagesJavascript The Web Warrior Series 6Th Edition Vodnik Test Bank Full Chapter PDFtina.bobbitt231100% (10)

- Role of Rahu and Ketu at The Time of DeathDocument7 pagesRole of Rahu and Ketu at The Time of DeathAnton Duda HerediaNo ratings yet

- Meta Trader 4Document2 pagesMeta Trader 4Alexis Chinchay AtaoNo ratings yet

- MiQ Programmatic Media Intern RoleDocument4 pagesMiQ Programmatic Media Intern Role124 SHAIL SINGHNo ratings yet

- Ten - Doc. TR 20 01 (Vol. II)Document309 pagesTen - Doc. TR 20 01 (Vol. II)Manoj OjhaNo ratings yet

- 14 Jet Mykles - Heaven Sent 5 - GenesisDocument124 pages14 Jet Mykles - Heaven Sent 5 - Genesiskeikey2050% (2)

- Training Effectiveness ISO 9001Document50 pagesTraining Effectiveness ISO 9001jaiswalsk1No ratings yet

- Building Bridges Innovation 2018Document103 pagesBuilding Bridges Innovation 2018simonyuNo ratings yet

- Mastering ArpeggiosDocument58 pagesMastering Arpeggiospeterd87No ratings yet

- Organisation Study of KAMCODocument62 pagesOrganisation Study of KAMCORobin Thomas100% (11)

- Important TemperatefruitsDocument33 pagesImportant TemperatefruitsjosephinNo ratings yet

- Battery Genset Usage 06-08pelj0910Document4 pagesBattery Genset Usage 06-08pelj0910b400013No ratings yet

- (Template) Grade 6 Science InvestigationDocument6 pages(Template) Grade 6 Science InvestigationYounis AhmedNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics AssignmentDocument12 pagesProfessional Ethics AssignmentNOBINNo ratings yet

- GCSE Ratio ExercisesDocument2 pagesGCSE Ratio ExercisesCarlos l99l7671No ratings yet

- Examination of InvitationDocument3 pagesExamination of InvitationChoi Rinna62% (13)

- Popular Restaurant Types & London's Top EateriesDocument6 pagesPopular Restaurant Types & London's Top EateriesMisic MaximNo ratings yet

- Md. Raju Ahmed RonyDocument13 pagesMd. Raju Ahmed RonyCar UseNo ratings yet

- EE-LEC-6 - Air PollutionDocument52 pagesEE-LEC-6 - Air PollutionVijendraNo ratings yet

- Italy VISA Annex 9 Application Form Gennaio 2016 FinaleDocument11 pagesItaly VISA Annex 9 Application Form Gennaio 2016 Finalesumit.raj.iiit5613No ratings yet

- 11th AccountancyDocument13 pages11th AccountancyNarendar KumarNo ratings yet

- Explaining ADHD To TeachersDocument1 pageExplaining ADHD To TeachersChris100% (2)

- Excel Keyboard Shortcuts MasterclassDocument18 pagesExcel Keyboard Shortcuts MasterclassluinksNo ratings yet

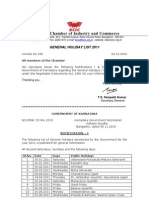

- BCIC General Holiday List 2011Document4 pagesBCIC General Holiday List 2011Srikanth DLNo ratings yet

- De So 2 de Kiem Tra Giua Ki 2 Tieng Anh 8 Moi 1677641450Document4 pagesDe So 2 de Kiem Tra Giua Ki 2 Tieng Anh 8 Moi 1677641450phuong phamthihongNo ratings yet

- Vegan Banana Bread Pancakes With Chocolate Chunks Recipe + VideoDocument33 pagesVegan Banana Bread Pancakes With Chocolate Chunks Recipe + VideoGiuliana FloresNo ratings yet

- BI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014Document1 pageBI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014scribdNo ratings yet

- Complicated Grief Treatment Instruction ManualDocument276 pagesComplicated Grief Treatment Instruction ManualFrancisco Matías Ponce Miranda100% (3)

- Sigma Chi Foundation - 2016 Annual ReportDocument35 pagesSigma Chi Foundation - 2016 Annual ReportWes HoltsclawNo ratings yet

- Tanroads KilimanjaroDocument10 pagesTanroads KilimanjaroElisha WankogereNo ratings yet