Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Queerying Near Eastern Archaeology

Uploaded by

Ana DjuricicCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Queerying Near Eastern Archaeology

Uploaded by

Ana DjuricicCopyright:

Available Formats

Queerying Near Eastern Archaeology Author(s): Karina Croucher Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 37, No.

4, Debates in "World Archaeology" (Dec., 2005), pp. 610-620 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40025096 Accessed: 03/04/2010 18:06

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=taylorfrancis. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Archaeology.

http://www.jstor.org

Queerying Near Eastern archaeology

Karina Croucher

Abstract NearEastern the is traditionally characterized by a chronocentric approach, prioritizing archaeology study of chronology and 'culture groups'. Additionally,the sense of vision dominates most Both thesefactorsderivefrommodern,Western values.Using a case archaeological interpretations. study of the Skull Buildingat ayonii Tepesi, SoutheastAnatolia, I propose a differentway of and writingabout Near Easternarchaeology. experiencing

Keywords Queer archaeology;Near Eastern archaeology;Neolithic; Anatolia; ayonu Tepesi; senses; architecture. chronocentricism;

The explicit use of the concept of 'queer' in archaeology has had some high-profile exposure in recent years. In 2000, after the publication of a handful of archaeological papers in various journals by a small number of archaeologists, one of the themed issues of World Archaeology, edited by Thomas Dowson, presented the potential of 'queer archaeologies' to a wider and international audience. This issue provided inspiration for the 'Que(e)ring Archaeology' theme for the 2004 Chacmool conference. Here, the use of queer theory in archaeology was explored across a number of temporally and geographically diverse areas of study within archaeology, from Palaeolithic and Neolithic prehistory to Roman and historical archaeology. Despite this high-profile event, it cannot be said that queer theory has had an overwhelming impact on the disciplinary practice of archaeology; there remains much scope for its further development within archaeological practice, research and interpretation. In this paper I explore the potential of queerfor Near Eastern archaeology. To date, queer theory has been used predominantly to explore alternative sexualities in the past or to critique certain representations of sexualities. Although this line of enquiry and critique is important for archaeology, 'queerying archaeology does not involve looking for homosexuals, or any other supposed sexual deviant for that matter, in the

O Routledge

l\

WorldArchaeology Vol. 37(4): 610-620 Debates in WorldArchaeology

2005 Taylor & Francis ISSN 0043-8243 print/ 1470- 1375 online DOI: 10. 1080/00438240500418664

Tayiors.Franciscroup

Queerying Near Eastern archaeology 611 past. Nor is it concerned with the origins of homosexuality' (Dowson 1998: 287). Queer theory is much more than that; it can potentially disrupt all aspects of heteronormative practice in archaeology. Consequently, queer theory should be incorporated into a package of approaches which challenge the unjustified projection of modern values and beliefs onto the past, exploring alternative ways of being in and experiencing the world, including sexuality, gender, identity, personhood, families, human/animal relationships, labour and ideologies in the past. Also, as Barbara Voss has pointed out, 'queer theory citations were especially common in introductions to edited volumes and conference proceedings and rare in archaeological case studies, suggesting that queer theory has been used predominantly to theorize the feminist archaeological project as a whole rather than to interpret archaeological evidence' (2000: 186). For queer to have any real impact in archaeology the effect on specific case studies must be immediately observable. In the following section I apply a queer critique to one aspect, albeit a fundamental aspect, of Near Eastern archaeology. Drawing on this critique, I then offer an alternative way of producing Near Eastern archaeologies.

Chronocentricismin Near Eastern archaeology A number of writers have offered a critique of chronocentricism in archaeology. Using queer theory, however, Dowson (2001) has offered a queer critique of chronocentrism. He suggests that the need for chronology in archaeological interpretation is a consequence of the dominance of masculist ideals and values in archaeology. The discipline has been established, controlled and dominated by white, heterosexual males, whose values are continuously perpetuated in the discipline; thus, 'every interpretation of the past is always already heteronormative, in terms of both its content and its methodology' (Dowson 2006). Chronocentricism 'is not simply the result of some objective, sex-neutral chosen way of approaching the past'; rather, 'it is a methodological manifestation of phallocentric values and ideals' (Dowson 2001: 316-17). This, according to Dowson, is particularly noticeable in rock art studies, where 'without a chronology your research is irrelevant', unscientific (Dowson 2001: 316). But interpretations derived from rock art analyses are no less valid than those derived from more traditional archaeological pursuits where there exists a 'firm' chronological framework. It is not just rock art studies which suffer from chronocentrism in archaeology. Within Near Eastern archaeology there is a strong reluctance to study aspects of the past that are not grounded within a 'solid chronological framework'. In this way, Near Eastern archaeological research is chronocentric in character- large-scale, grand narratives, which result from an exercise whereby sites are slotted into their position within both chronological and regional frameworks, dominate constructions of the past in this region. The grand narrative follows the adoption of agriculture and a 'Neolithic' lifestyle, through to urbanism and city-states. Essentially, the purpose of most investigations here is to refine the regional and temporal frameworks, and the position of sites within these according to their perceived 'culture types'. Labels such as PPNB, Halaf, Uruk, Ubaid are applied to sites according to the perceived 'package' of material indicators, such as pottery, lithic technology, architecture, mortuary treatment, subsistence, etc. (see Campbell (1998,

612 Karina Croucher 1999, 2000) and Croucher and Campbell (in press) for a discussion on the problems associated with these labels). The significance of Near Eastern sites is afforded by our 'ability to pinpoint them with some precision within a fixed chronological framework' (Matthews 2003: 64-5). It seems that, for any archaeological research to be taken seriously in Near Eastern archaeology, it must first be unambiguously situated within a specific accepted intellectual framework which is itself constructed on a 'firm' chronological and typological classification of excavated material, with accurate dating seen as 'essential' when discussing 'Upper Paleolithic, Epipaleolithic, Neolithic and Chalcolithic sites' (Bar-Yosef 1998: xiv). For many sites this is as far as interpretation goes, with the chronological and typological frameworks used predominantly to investigate developing social hierarchy. This heavily chronocentric approach is prioritized at the expense of more theoretically informed interpretation and discourse, with attempts to pin down the exact chronology or date of material often distracting from in-depth examinations and explorations of the evidence at hand. For example, at a recent Near Eastern conference, I sat through many fascinating papers which attempted to bring about new and challenging approaches to the understanding of Near Eastern archaeology. Sadly, I felt, the discussion that followed most of these presentations centred almost exclusively on minute aspects of chronological or typological detail, and the broader contribution which the papers attempted to make was lost or ignored. In a further example, Flannery (1998: xvi), writing in The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land, states one of the strengths of the volume to be its 'common-sense use of social evolutionary theory', praising the use of 'full-coverage surveys, followed by tables of site sizes which allow the discovery of settlement hierarchies. Using rank-size graphs, they determine the degree of political integration of a region.' Flannery states that interpretation in the volume is 'scientific, empirical, statistical, materialist, explanationseeking', rather than being based on 'archaeology's latest messianic cult, that anti-science, anti-materialist, anti-comparative movement calling itself "post-processualism"', the practitioners of which, '(few of whom spend much time on archaeological sites), [he suggests, believe] the past is merely a "text" with no objective reality, to be interpreted intuitively'. The approach to interpretation in archaeology is obvious. Archaeological research is valid only when it is firmly embedded within accepted methodological frameworks, which are developed through methods that are perceived to be 'scientific'. This situation is particularly tragic given that the methodologies on which we base our chronological frameworks are themselves obviously not unproblematic. These methodologies have usually developed around an understanding of the past which is based on decades of colonial looting, resulting in large quantities of unprovenanced material, which is still encouraged today by affluent Western art markets, as well as historic issues associated with problematic excavation and recording standards. It is, therefore, ironic and unfortunate that the discipline continues to place so much importance on chronology often at the expense of exploring other, more interesting lines of enquiry. This situation can be challenged through a bottom-up approach to the past; interpretations which examine the small-scale or specific elements of the archaeological evidence are just as valid as the search for large-scale patterns and narratives, even if often seen as 'stepping away from the accepted methodologies of both archaeological and

Queerying Near Eastern archaeology 613 historical practice . . . stepping away from the normative' (Dowson 1998: 289). We should look beyond defining, and re-defining, 'cultural packages', these discrete social and chronological entities, and examine the smaller scale in archaeology first, accepting that a nice, neat pattern to grand narratives and the archaeological material often does not in reality exist. This approach can easily be taken with most archaeological evidence, and is especially fruitful, I believe, for Near Eastern archaeology due to the wealth of material available to us. Barrett (2005), referring to the British Bronze and Iron Ages, argues that attempts to provide neat chronological and typological patterns negate the actual complexity of the evidence at hand. This is as true for Near Eastern archaeology.

Queering the archaeological gaze Archaeological practice not only has the tendency to be chronocentric, it also privileges and prioritizes 'vision' in our interpretations of the past. The importance of vision is overplayed in archaeology, despite ethnographic accounts documenting the 'variety of ritual experience' which reach beyond merely describing what events 'looked' like (Watson 2001: 179). This too is as a result of modern, Western experiences which prioritize vision (MacGregor 1999: 264). In the West we take eye care and developments in optic medicine for granted. Yet, for anyone with poor eyesight, leaving the house without glasses or contact lenses introduces a whole new experience of the world - clocks you cannot see, faces you cannot recognize and so on. That this experience of the world is very real to anyone without modern eye care is often forgotten, yet if we imagine living in such a world it is not that difficult to begin to appreciate how different an experience life (and death) would be. Embedded in this modern Western experience of prioritizing vision is the relationship between the viewer and the viewed, as with the viewer and the painted (Hirsch 1995: 3; Thomas 1993: 22), with its roots in modern, post- Renaissance thinking, where the painter began to create realistic impressions of the landscape and other subjects (Thomas 1993: 21). This relationship is discussed by Thomas as being a gendered gaze, a voyeuristic relationship, comparable to the 'male gaze' on the female actresses of early cinema, with the object (woman or landscape) being there to be looked at, or gazed upon, by the male, detached and voyeuristic, observer (Thomas 1993: 24-5). Such a 'male gaze' on the female subject, as is inherent in our way of observing the past, is not only a gendered gaze, it is also a heterosexual gaze - masculist and heteronormative. As Claassen (2000), Dowson (2000, 2006) and She (2000) argue, such a hetero-normative and masculist approach is inherent in archaeology, present in much of our 'observations' of archaeological material. Even when digging and recording we tend to focus on visual aspects, forgetting the role of other senses: sound, touch, taste and smell. We are further removed from our subject - we take photographs, draw plans and sections, and situate finds on site plans, all of which is in line with the 'male gaze', placing us as distanced observers. If prioritizing vision is an aspect of methodological practice that is inherently heterocentric (and androcentric), then an approach that investigates and explores in archaeological material the role of other senses is a challenge to the heteronormative in

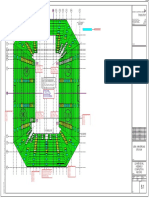

614 Karina Croucher archaeology. Together with Stuart Campbell I have briefly explored just such an approach elsewhere (Croucher and Campbell in press), and I should like to outline such an interpretation further here. The 'Skull Building' at aydnii Tepesi in Southeast Anatolia, said to date from the mid-ninth millennium to mid-seventh millennium bc, is well known for housing the secondary burials of over 450 persons, as well as the remains of a number of aurochs. Throughout at least five building phases this structure housed secondary human remains, with an apparent special selection of skulls and long bones. Traditional approaches to aydnii use the site to explore and reinforce chronological frameworks, neglecting discussion of the many other types of evidence. For example, the site has been incorporated into a wider study of a Near Eastern skull cult, or interpretations have focused either on the site's remarkable architecture or on its subsistence economy (Bienert 1991: Cauvin 1994: 93; Redman 1983: 189; Ozdogan and Ozdogan 1998: 588). Until the recent publications by M. and A. Ozdogan in 1998 and A. Ozdogan in 1999 relatively little work had been undertaken investigating mortuary remains and buildings of special significance at ayonii. Other recent studies have focused on a general overview (i.e. Verhoeven 2002), assessing the ritual nature of the site as a whole, implementing a broader approach to the archaeology, searching for similarities and patterns in the material between this and other sites, rather than an in-depth investigation of specific aspects of the archaeological evidence here. Before I outline an alternative narrative, I summarize the various architecturalphases of the Skull Building (based on Schirmer (1990) and Ozdogan (1999)). The first building phase, termed BMlc, is the earliest structure of the Skull Building. The surviving northern area consists of a double-walled apsidal structure and buttresses, containing many human skulls which had been placed on the main floor (Schirmer 1990: 379-81). In addition, there are two shallow pits dating to BM 1. The larger of the two pits contains both primary and secondary burials, as well as auroch skulls and horns, and the second, smaller pit contains secondary burials of fifteen people, the bones of which displayed cut marks and signs of defleshing activities (Ozdogan 1999: 47). The later Skull Building, BM2, underwent several building phases. Initially, during the construction of BM2c, a deep trench was dug into the virgin soil, into which a series of cellar rooms were dug. Stone slabs were then used to cover these cellar rooms, providing a floor for the northern part of the new building. This floored area was then surrounded by walls to the north, east and west, with a courtyard or large room to the south. This southern area was at a lower level than the flagstone floor. Two upright stone slabs were then put in place, aligned with the walls of the cellars below. Although walls surrounding the southern area are lost to erosion, it seems that the area was bordered with benches around the outer wall, with a channel-like double wall on the eastern side (Schirmer 1990: 380-1). What is immediately apparent is a significant use of the architecture to divide the space, using both the height change and upright stones to mark out a separation between the open southern area, and the more private northern area. In the building's floor a depression, containing cattle horns, was located roughly between the upright stone slabs at the southern edge of the step (Schirmer 1990: 381-2); again, an architectural association referring back to the first phase of the Skull Building. All the cellars contain human remains. The western cellar held over ninety human skulls, which were placed in rows and

Queerying Near Eastern archaeology 615 oriented to either the east or west (Ozbek 1992), along with the consecutive piling up of long bones. Clearly within this cellar there is a specific selection and ordering of bones. Further alterations during BM2b saw the encasement of the upright stones within the construction of dividing walls corresponding to the cellars below, dividing the northern space into three chambers (Schirmer 1990: 382). The northern part of the building was becoming increasingly private and segregated through the construction of the dividing walls. Later, during the building phase of BM2a, there were further restrictions with the addition of walls with doorways segregating the northern rooms and the southern area, with the floors of the northern chambers raised and also paved with stone. The building's modifications would have dictated movement between the separate chambers and southern area, carrying implications for the use of space, movement and ideas of access and exclusion. Such changes in the architecture were not simultaneous events (Schirmer 1990), but are the results of a long sequence of changes both reflecting and dictating the building's use, altering how the building is experienced. The plan of the southern area remained unchanged through the building's life, and we know that during the final building phase it was surrounded by high walls. We see the use of lime plaster as a flooring material for the first time in the Skull Building during BM2b, although it is used earlier in domestic architecture. During later phases the southern floor is repeatedly replastered, sealing the associated pits (Schirmer 1990). We also witness the same repeated events here with the raising of the chamber floors to the north and the repeated plastering of the southern floor. There appears to be a certain correlation between the division of space and the significance of substances observed in both the Skull Building and in contemporary domestic architecture during early phases of the site, when domestic structures were also divided into northern and southern sections. The northern areas were again raised floor surfaces, with larger rectangular rooms, entrances, a fireplace and plastered floors to the south (Ozdogan 1999: 43). The lack of a fireplace in the Skull Building again suggests implications for the building's use. Both domestic architecture and the Skull Building display a separation between northern and southern areas, with a plastered southern area a feature of both. The location of the entrance to the south is a further common feature, although this is only presumed in the Skull Building as the southern end is eroded. These similarities suggests material substances held some importance, the northern floor area always constructed of stone, in contrast to the southern plastered area. The use of lime plaster has associated labour and resource implications, believed to be the result of largescale, community-wide organization and co-operation, as the accumulation of resources and the processes involved would be beyond the capabilities of production on an individual basis (Garfinkel 1987: 70-2). During BM2a the placement of human skulls continued: forty-nine skulls were recovered from chamber rooms above the cellars, over half of which, accompanied by animal bones, were recovered from the Eastern room (Ozdogan 1999). The human skulls were examined by Ozbek of Ankara University (1988: 127). The skulls belonged to adults and juveniles, male and female, a high proportion of them (83 per cent) belonging to young adults. There is an absence of children aged under about 2lA years old (Ozbek 1988: 128). This contrasts noticeably with the human remains recovered from beneath house floors, where a large proportion were remains of infants. Interestingly, at ay6nii there is a

616 Karina Croucher significantly high infant mortality rate, suggested to be due to either malnutrition or possibly bacterially contaminated food used to supplement breast milk, as well as infectious diseases (Yakar 1991: 305). From the remains studied so far only 50 per cent of the population were expected to reach maturity (15+ years), with only 2 per cent living to reach 50 years or more (Yakar 1991). Ozbek notes that at ayonii the average age at death is 36.1 years (1998: 575). High mortality rates, also observed among contemporary sites (Yakar 1991: 305), would traditionally contribute to arguments in support of motivations of fertility and life behind rituals. This is, however, a decidedly Western interpretation of the data, one where death is usually feared and life prolonged. This situation is not universal, and as such may not have been a feature or motivation behind activities at aydmi, where it is evident from the treatment of remains that death was understood in very different terms from our perceptions today. Furthermore, although the average age at death is low by modern, Western standards, this was no doubt normal and expected at aydnii, and therefore may not have been as significant as we imagine. Although all the skulls from the chamber rooms were badly damaged by the fire which eventually destroyed the building, examination revealed that skulls were differently affected: at the time of the fire some skulls were dryer than others (Ozbek 1988: 129). The skulls were apparently deposited into the building at differenttimes; they were not the result of a single event, rather of repeated activity. Many of the skulls still had their mandibles and second vertebrae, and some display cut-marks (Ozbek 1988: 129; Loy and Wood 1989: 452), suggesting the head was cut from the body. This activity may be linked to the stone slab, often interpreted as a table or altar, placed in the southern area of the Skull Building. On this large (2m square and 10cm deep), highly polished slab the residue of 9000year-old blood was recovered, which was identified by Loy and Wood (1989) as human haemoglobin, matching the form, size and shape of modern human blood crystals (for criticisms of blood residue analysis see Fiedel 1996, 1997; Grace 1996; Tuross and Barnes 1996). Further blood residues were also recovered and identified as belonging to auroch and sheep. Blood crystals, from both human and auroch, were found on the distal end of a large (20 cm long), black flint blade retrieved from the Skull Building (Wood 1998: 764). Wood suggests that the presence of human blood, mingled with that of sheep and auroch, is indicative of 'at least, an occasional use of the "slab" for some form of ritual dismemberment' (Wood 1998: 764). Both sacrifice and preparation of bodies for secondary burial are suggested (Ozdogan 1999: 52). Lithic analysis of blades from the Skull Building revealed that these had apparently only been used to cut bones, meat and nervous tissue (Caneca 2001). Throughout the use of the Skull Building, human remains were a focus of activities taking place there. But, rather than simply attending to the visual aspects these remains would have presented, we should also consider the other senses in attempting to construct some of these activities. The Skull Building itself would have been open to different experiences determined by the part of the building any person was situated within. The southern part of the building was open and public, offering a venue for display for whatever activities were taking place on the stone slab, evidently involving the cutting, disarticulation or processing of human and animal remains in some way. This suggests an amount of blood and other bodily remains would have been present. This is far removed from the sanitized remains we recover from the archaeological record, where it is easy to distance the dry,

Queerying Near Eastern archaeology 617 clean bone from the events and practices which would have been taking place. In many cases, the skulls had their vertebrae and mandibles attached, clearly interredin a fleshed, or partly fleshed, state. The processes involved would have involved cutting, involving effort, blood and other bodily substances: clearly a very tactile experience. Recent art work by Anya Gallaccio, a 2003 Turner art prize entrant, has explored the sense of smell through the use of natural and rotting materials in her pieces, whereby the artwork gradually rots and decays, emitting aromas, investigating themes of death and decay through art, designed to stimulate more than just sight. Such pieces are designed to prompt us to think about other senses, and should be taken seriously in archaeology. Smell would undoubtedly have featured heavily in the experience of the Skull Building. Although some remains were seemingly fresher, many were interred with at least some flesh, leading to decay, and inevitably the odour of decomposing flesh. Smell, unlike many other senses, is difficult to ignore; it is penetrating and unavoidable - decomposing flesh is an especially poignant smell (Seigal 1983: 9). The smell emitting from the Skull Building may have been a contributory factor to its 'liminal' position on site (although it should be noted that revulsion to certain smells is certainly culturally constructed rather than universal; as Hertz (1960 [1907]: 32) advises, we should not credit people in the past with the same (in)tolerances as ourselves). The Skull Building was set back, secluded from other activities, in the eastern area of the site. This area was kept separate throughout the occupation of the site, its location suggesting it was considered a separate arena, not for everyday life and activity. The interior of the Skull Building, with its segregated areas of activity, may display its own liminal or dangerous areas. The division of space could have served to both reflect and construct internal activity. At certain times sound may have marked events and enhanced the experience of the Skull Building. Possibly music, chants and song would have been heard, the noise enhanced by the stone walls. Perhaps there were noises of animals, or even people, as they were led to the stone slab. Or perhaps even silence was observed while events were taking place. Whatever the case, clearly the sounds present would have a substantial influence on the experience of events in the Skull Building. Light would also have certainly played a role; whether events were taking place at night or during the day. The possible use of torches to illuminate the Skull Building, emitting flickering half-light, would also have enhanced the way in which people experienced the building. Also offering a further insight into use of the Skull Building is the recovery of fragmentary pieces of early white-ware. Although samples from the Skull Building were too fragmentaryfor analysis, other pieces large enough for identification are extraordinary in their size, originating from vessels just under a meter in diameter and 30 cm in height (Ozdogan and Ozdogan 1993: 93). Because they are so large, it seems obvious these vessels would have had a communal use - perhaps a ceremonial use or for cleansing activities. Perhaps these vessels contained liquids and substances that were consumed - suggesting taste was a part of the experience. The sense one gets of the Skull Building at ayonii Tepesi is one that involved people of different ages, animals, blood and activities that engaged all the senses. It may very well be difficult to construct exactly what experiences took place in the Skull Building; but it is possible to investigate the site in a multi-sensual way by exploring the archaeological data in ways not done previously. Instead of 'seeing' the data as a tool for identifying the

618

Karina Croucher

presence of certain cultural groups at specific times in specific places, these same data can be examined in terms of human senses to gain some insight into how these people may have experienced the site. What may appear to us today as being something quite gruesome, it is unlikely that the activities that took place at aydnii Tepesi would have produced similar reactions in the people who lived there, but it does not follow that their experiences were sanitized or sense-less. Through such an approach to individual sites, as well as individual features therein, we can counter heteronormative practice in archaeology, and extend the potential of queer critique in archaeology.

Acknowledgements

I would especially like to thank Thomas Dowson for his suggestion, advice and support, as well as Hannah Cobb for organizing the session at the Chacmool Que(e)rying Archaeology conference, 2004. I also thank Stuart Campbell who contributed to this paper through previous research on the Domuztepe Project and advice during my PhD.

School of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, Hartley Building, L69 3GS, Liverpool, UK

References Barrett, J. C. 2005. Desperately seeking the end of the Bronze Age: the return to All Cannings Cross. Paper presented at an archaeology research seminar, University of Manchester, February. Bar-Yosef, O. 1998. Prehistoric chronological framework. In The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land, 2nd edn (ed. T. E. Levy). Leicester: Leicester University Press, pp. xiv-xvi. Bienert, H-D. 1991. Skull cult in the Prehistoric Near East. Journal of Prehistoric Religion, 5: 9-23. Campbell, S. 1998. Problems of definition: the origins of the Halaf in north Iraq. In Subartu IV, Vol. 1, Landscape, Archaeology, Settlement (ed. M. Lebeau). Brussels: Brepols, pp. 39-52. Campbell, S. 1999. Archaeological constructs and past reality on the upper Euphrates. In Archaeology of the Upper Syrian Euphrates: The Tishrin Dam Area (eds G. del Olmo Lete and J. L. M. Fenollos). Barcelona: Editorial Ausa, pp. 573-83. Campbell, S. 2000. Questions of definition in the Early Bronze Age of the Tishreen Dam. In Chronologies des Pays du Caucase et de V Euphrates aux IVe-IIIe Millenaires (eds C. Marro and H. Hauptmann). Istanbul and Paris: de Boccard, pp. 53-64. Caneca, I. 2001. Upper Mesopotamia in its regional context during the early Neolithic. In discussion at the Central Anatolian Neolithic e-Workshop. Available at: http://www.canew.org/ hauptmanndeb.htm Cauvin, J. 1994. The Birth of the Gods and the Origins of Agriculture(trans. T. Watkins). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Claassen, C. 2000. Homophobia and women archaeologists. WorldArchaeology, 32(2): 173-9. Croucher, K. and Campbell, S. In press. Dying for a change? Bringing new senses to Near Eastern Neolithic mortuary practice. In Chacmool Conference Proceedings, Queer(y)ing Archaeology, Calgary, Canada, October 2004.

Queerying Near Eastern archaeology 619

Dowson, T. A. 1998. Homosexuality, queer theory and archaeology. Reprinted in Interpretative Archaeology (ed. J. Thomas). Leicester: Leicester University Press, 2000, pp. 283-9. Dowson, T. A. 2000. Why queer archaeology? An introduction. World Archaeology, 32: 161-5. Dowson, T. A. 2001. Queer theory and feminist theory: towards a sociology of sexual politics in rock art research. In TheoreticalPerspectives in Rock Art Research (ed. K. Helskog). Oslo: Novus Press, pp. 312-29. Dowson, T. A. 2006. Archaeologists, feminists and queers: sexual politics in the construction of the past. In Feminist Anthropology:Perspectives on our Past, Present, and Future (eds P. L. Geller and M. K. Stockett). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, in press. Fiedel, S. J. 1996. Blood from stones? Some methodological and interpretative problems in blood residue analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science, 23: 139-74. Fiedel, S. J. 1997. Reply to Newman et al. Journal of Archaeological Science, 24: 1029-30. Flannery, K. V. 1998. Introduction to second edition. In The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land (ed. T. E. Levy). Leicester: Leicester University Press, pp. xvii-xx. Gallaccio, A. 2003. preserve beauty. Turner Prize entrant. Garfinkel, Y. 1987. Burnt lime products and social implications in the pre-pottery Neolithic B villages of the Near East. Paleorient, 13(1): 69-76. Grace, R. 1996. Review article. Use-wear analysis: the state of the art. Archaeometry, 38: 209-29. Hertz, R. 1960 [1907]. Death and the Right Hand. Aberdeen: Cohen & West. Hirsch, E. 1995. Landscape: between place and space. In The Anthropology of Landscape (eds E. Hirsch and M. O'Hanlon). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Loy, T. and Wood, A. R. 1989. Blood residue analysis at ayonii Tepesi, Turkey. Journal of Field Archaeology, 16: 451-60. MacGregor, G. 1999. Making sense of the past in the present: a sensory analysis of carved stone balls. WorldArchaeology, 31: 258-72. Matthews, R. 2003. The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: Theories and Approaches. London: Routledge. Ozbek, M. 1988. Culte des cranes humains a aydnii. Anatolica, 15: 127-37. Ozbek, M. 1992. The human remains at ay6nii. American Journal of Archaeology, 96: 373. Ozbek, M. 1998. Human skeletal remains from Aikli, a Neolithic village near Aksaray, Turkey. In Light on Top of the Black Hill (eds G. Arsebiik, M. Mellink and W. Schirmer). Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari, pp. 567-79. Ozdogan A. 1999. ayomi. In Neolithic in Turkey (ed. M. Ozdogan). Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yay, pp. 35-63. Ozdogan, M. and Ozdogan, A. 1993. Pre-Halafian pottery of Southeastern Anatolia with special reference to the ayonii sequence. In Between the Rivers and Over the Mountains: A. Palmieri Dedicata (eds M. Frangipane, H. Hauptmann, M. Liverani, P. Matthiae and M. Mellink). Rome: Dipartimento di Scienze Storiche Archeologiche e Antropologiche, pp. 87-103. Ozdogan, M. and Ozdogan, A. 1998. Buildings of cult and the cult of buildings. In Light on Top of the Black Hill (eds G. Arsebiik, M. Mellink and W. Schirmer). Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari, pp. 581-93. Redman, C. L. 1983. Regularity and change in the architecture of an early village. In The Hilly Flanks and Beyond (eds T. C. Young, P. E. L. Smith and P. Mortensen). Chicago, IL: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 189-206. Schirmer, W. 1990. Some aspects of building at the 'Aceramic-Neolithic' settlement of ayonu Tepesi. WorldArchaeology, 21: 363-87.

620 Karina Croucher

Seigel, J. T. 1983. Images and odours in Javanese practices surrounding death. Indonesia, 36: 1-14. She 2000. Sex and a career. World Archaeology, 32: 166-72. Thomas, J. 1993. The politics of vision and the archaeologies of landscape. In Landscape: Politics and Perspectives (ed. B. Bender). Oxford: Berg, pp. 19-48. Tuross, N. and Barnes, I. 1996. Protein identification of blood residues on experimental stone tools. Journal of Archaeological Science, 23: 289-96. Verhoeven, M. 2002. Ritual and ideology in the pre-pottery Neolithic B of the Levant and Southeast Anatolia. CambridgeArchaeological Journal, 12(2): 233-58. Voss, B. L. 2000. Feminisms, queer theories, and the archaeological study of past sexualities. World Archaeology, 32: 180-92. Watson, A. 2001. The sounds of transformation: acoustics, monuments and ritual in the British Neolithic. In The Archaeology of Shamanism (ed. N. Price). London: Routledge, pp. 178-92. Wood, A. R. 1998. Revisited: blood residue investigations at ayonii, Turkey. In Light on Top of the Black Hill (eds G. Arsebiik, M. Mellink and W. Schirmer). Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari, pp. 763-4. Yakar, J. 1991. Prehistoric Anatolia: The Neolithic Transformationand the Early Chalcolithic. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, Monograph series no. 9.

Karina Crouchercompleted her PhD at the University of Manchester where her research has focused on treatment of the body in the Neolithic Near East. She has also studied the British Neolithic, where theoretical insights from the discipline influence her approach to Near Eastern archaeology. She is now based at Liverpool University, where she researches and teaches, as well as supporting teaching and learning in archaeology through her work with the Higher Education Academy.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- NHD Process PaperDocument2 pagesNHD Process Paperapi-203024952100% (1)

- Mecha World Compendium Playbooks BWDocument12 pagesMecha World Compendium Playbooks BWRobson Alves MacielNo ratings yet

- Based On PSA 700 Revised - The Independent Auditor's Report On A Complete Set of General Purpose Financial StatementsDocument12 pagesBased On PSA 700 Revised - The Independent Auditor's Report On A Complete Set of General Purpose Financial Statementsbobo kaNo ratings yet

- XII CS Material Chap7 2012 13Document21 pagesXII CS Material Chap7 2012 13Ashis PradhanNo ratings yet

- OM CommandCenter OI SEP09 enDocument30 pagesOM CommandCenter OI SEP09 enGabriely MuriloNo ratings yet

- SPC FD 00 G00 Part 03 of 12 Division 06 07Document236 pagesSPC FD 00 G00 Part 03 of 12 Division 06 07marco.w.orascomNo ratings yet

- Jacob Stewart ResumeDocument2 pagesJacob Stewart Resumeapi-250063152No ratings yet

- Unit 1 Module 3 Rep in PlantsDocument26 pagesUnit 1 Module 3 Rep in Plantstamesh jodhanNo ratings yet

- 2Document8 pages2Eduardo Antonio Comaru Gouveia75% (4)

- Dry Compressing Vacuum PumpsDocument62 pagesDry Compressing Vacuum PumpsAnonymous zwSP5gvNo ratings yet

- Gis Data Creation in Bih: Digital Topographic Maps For Bosnia and HerzegovinaDocument9 pagesGis Data Creation in Bih: Digital Topographic Maps For Bosnia and HerzegovinaGrantNo ratings yet

- BiografijaDocument36 pagesBiografijaStjepan ŠkalicNo ratings yet

- NAV SOLVING PROBLEM 3 (1-20) .PpsDocument37 pagesNAV SOLVING PROBLEM 3 (1-20) .Ppsmsk5in100% (1)

- Fuzzy Gain Scheduled Pi Controller For ADocument5 pagesFuzzy Gain Scheduled Pi Controller For AOumayNo ratings yet

- Module 5 What Is Matter PDFDocument28 pagesModule 5 What Is Matter PDFFLORA MAY VILLANUEVANo ratings yet

- Lacey Robertson Resume 3-6-20Document1 pageLacey Robertson Resume 3-6-20api-410771996No ratings yet

- 2nd Term Project 4º Eso Beauty Canons 2015-16 DefinitivoDocument2 pages2nd Term Project 4º Eso Beauty Canons 2015-16 DefinitivopasferacosNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics: The Journal ofDocument11 pagesPediatrics: The Journal ofRohini TondaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER IV The PSYCHOLOGY of YOGA Yoga, One Among The Six Orthodox Schools of Indian ... (PDFDrive)Document64 pagesCHAPTER IV The PSYCHOLOGY of YOGA Yoga, One Among The Six Orthodox Schools of Indian ... (PDFDrive)kriti madhokNo ratings yet

- Data MiningDocument28 pagesData MiningGURUPADA PATINo ratings yet

- Literature Review Template DownloadDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Template Downloadaflsigfek100% (1)

- SDSSSSDDocument1 pageSDSSSSDmirfanjpcgmailcomNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction and Acute Management StrategiesDocument11 pagesPathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction and Acute Management StrategiesnwabukingzNo ratings yet

- Session 1Document18 pagesSession 1Akash GuptaNo ratings yet

- Pubb-0589-L-Rock-mass Hydrojacking Risk Related To Pressurized Water TunnelsDocument10 pagesPubb-0589-L-Rock-mass Hydrojacking Risk Related To Pressurized Water Tunnelsinge ocNo ratings yet

- Grammar and Vocabulary TestDocument5 pagesGrammar and Vocabulary TestLeonora ConejosNo ratings yet

- The Checkmate Patterns Manual: The Ultimate Guide To Winning in ChessDocument30 pagesThe Checkmate Patterns Manual: The Ultimate Guide To Winning in ChessDusen VanNo ratings yet

- Generation III Sonic Feeder Control System Manual 20576Document32 pagesGeneration III Sonic Feeder Control System Manual 20576julianmataNo ratings yet

- Virtual WorkDocument12 pagesVirtual Workdkgupta28No ratings yet

- Python in Hidrology BookDocument153 pagesPython in Hidrology BookJuan david Gonzalez vasquez100% (1)