Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Perniola - An Aesthetic of The

Uploaded by

Eugenio SantangeloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Perniola - An Aesthetic of The

Uploaded by

Eugenio SantangeloCopyright:

Available Formats

An Aesthetic of the "Grand Style": Guy Debord Author(s): Mario Perniola and Olga Vasile Source: SubStance, Vol.

28, No. 3, Issue 90: Special Issue: Guy Debord (1999), pp. 89-101 Published by: University of Wisconsin Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3685435 Accessed: 07/06/2010 00:08

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=uwisc. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Wisconsin Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to SubStance.

http://www.jstor.org

An Aesthetic of the "GrandStyle": Guy Debord

Mario Perniola

A Distancing from the World It is difficult today to determine what might correspond to that model of aesthetic excellence that Nietzsche defined with the expression "the grand style." Certainly, in the various arts, works keep being produced that correspond to the features of contained power, classical rigor and unbounded certainty;unfortunately they come to the attention of experts and the public with greater difficulty and more slowly than in the past, both because of literary, artistic and cultural overproduction, and widespread cynicism, superficiality,and insensibility. "Thegrand style," in fact, implies immediate concern, respect, memory-in a word, veneration. These aspects do not blend well with the general tone of contemporary daily experience, but precisely because of their rarity they may render "the grand style" the object of more diligent research and more zeal than ever. It is much more difficult, however, not just to find, but even to imagine "the grand style" as the quality of an action, a behavior or even an entire existence: in other words, as Nietzsche says, to consider it no longer simply art,but "reality, truth, life."Besides, Nietzsche himself taught diffidence about actions and behaviors that attribute to themselves all sorts of positive qualities, and he showed how, in most cases, they are secretly animated by opposite drives. In this specific instance, the philistinism of the rich and idle mob that glorifies Wagner's opera exemplifies exactly the opposite of "the grand style"; indeed cultural snobbism -as the word itself suggests: "sine nobilitate"-constitutes a manifestation of vulgarity and coarseness, of boasting ostentation that is at the antipodes of "grand style's" simplicity and purity. As for a whole life, globally considered, it seems that only a few short existences may aspire to all that, almost as if longevity required a long exercise of practical shrewdness, if not complicity with infinite shames. To recognize this is already a great achievement! For this reason, it is for me a source of great happiness to have met the man who in the second half of the twentieth century has been the

Substance# 90, 1999

89

90

Mario Pemiola

personification of "the grand style," Guy Debord, "doctor of nothing," as he defines himself (Panegyric13), but master of the ambitious, friend of rebels and the poor, secretly admired by the mighty, stirring great emotions, but cold and detached from himself and from the world. This is in fact the first condition of style: detachment, distance, suspension from disorganized affections,from immediate emotions, from unrestrainedpassions; hence there is a relationship between style and classicism that Nietzsche repeatedly underlined. Style, however, should not be considered a synonym for frigidity, insensibility, or worse, pedantic and stereotyped academicism. In order to master passions, they have to be there! Besides, style and passion have in common their imperious and constraining character;both require obedience and discipline. In Debord's case, detachment manifests itself first of all as completely extraneous to the worlds of academia, publishing, journalism, politics and media. Debord nourishes a deep disgust for the whole cultural establishment. He hates worldliness and snobbish frivolity that flirts with revolutionary extremism - the so-called "radicalchic." Finally,his disdain is not softened by inherited wealth: he affirmsthat he was "bor virtually ruined" (Panegyric 12). In an age in which ambitious people are ready to do everything to obtain political power and money, Debord's strategy exploits one factor: the admiration he inspires in those who see that political power and money are secondary to excellence and its recognition. This strategy aims at a kind of superiority similar to that of some of the ancient philosophers, like Diogenes, for whom coherence between principles and behavior was essential. However, this superiority is not so much embedded in an ethical background as an esthetic one: the tradition to which Debord belongs is one of poetic and artistic revolt. That tradition, which encountered an extraordinary development in the twentieth century avant-garde, dates back to the Middle Villon was the model Ages: the great fifteenth-century French poet FranCois for an encounter between culture and alternative (in his case, even criminal) conduct, handed down through the centuries. Debord explicitly recognizes that heritage, but takes it further with a qualitative leap, since he refuses the exercise of poetry and art, maintaining that they must be overcome-that is to say, in Hegelian terms, they have to be suppressed and realized in ? 191 and ff.)According to Debord, revolutionary theory and practice(Society, the overcoming of art must not be postponed to a distant future, as some utopian thinkers propose, but is an urgent need of the time in which we live: it is not so much a question of foreshadowing a society to come than of obeying the very powerful command coming from the historical and social

Substance# 90, 1999

An Aesthetic of the "GrandStyle" Style"

91

hic et nunc. In this way, Debord also dissociates himself from those literary, poetic and artistic milieus which, despite being foreign to every form of institutionalization, persevere in practicing activities that can at any time be recuperated by the cultural establishment. It is not by chance that I got in touch with Debord after a conflict that in 1966 opposed me to the Surrealist movement. One has to add to all this his distance from all political-revolutionary organizations and trends prevailing in his age: Debord felt he was carrying on the heritage of the "councilcommunism" of the 1920s,developed in France ou Barbarie. This choice led him to a by theoretical journals such as Socialisme total refusal of any Leninist, Trotskyist,Maoist or Third-Worldposition: in his view, the so-called socialist regimes are forms of state capitalism, governed by a party bureaucracy that assumes the right to speak in the name of the proletariat whom it actually owns (Society,? 102).At the same time, Debord also distances himself from anarchism, which abandons the human being to individual whim; he does not doubt that the highest level of revolutionary theory has been reached by Marx, and not by Bakunin. If by "political" one means the distinction between "friends" and "enemies," together with the effort to increase the number of the former, there is in Debord a radical "unpoliticization" leading to isolation. That is, moreover, one of the reasons why we broke off our relationship in spring 1969. Approval and effectiveness obtained through sympathy, agreement and a good predisposition towards others was certainly not included in Debord's style. In this, he followed Nietzsche's opinion, according to which the greatness of the soul is not compatible with amiable virtues: "The grand style excludes the pleasant" (Nachgelassene,1972, 18, 1). In an era when amiability and ease are the most appreciated qualities, Debord faces his contemporariesin a bitter and rough manner,almost as if today only a similar attitude could arouse interest and excite passion. He writes: "[...] I never went looking for anyone, anywhere. My entourage has been composed only of those who came on their own accord, and knew how to make themselves accepted" (Panegyric,17). In fact, this did not prevent, at least in the second half of the 1960s, a sociability that recognized itself in a theoretical project and in a life-style formed around Debord. Its axis was constituted by the "Situationist International," a movement that Debord founded in 1957 together with other members of the art avant-garde, and which produced, over twelve years, twelve numbers of a journal,L'Internationale Situationniste, that was brilliantin content and elegantly produced. The SI- as it was called, with a fortunate acronym-was a closed group that made a clear-cut

Substance# 90, 1999

92

Mario Pemiola Perniola

distinction between members and sympathizers: it was ruled by a sort of collective responsibility,according to which individual theoreticalstatements and behaviors automatically involved everyone else. This feature, similar to one of the aspects of religious sects, has in the case of the SI an aesthetic meaning, referringto the importance of the constraining and binding element of style; as Nietzsche writes, it implies the erasure of individual specificity, a deep sense of discipline and a repugnance for a disorganized and chaotic nature (Gay Science ? 290). However, these requirements, which perfectly corresponded to Debord's way of being, did not match the temper of other members of the SI, who were either much more expansive and extroverted, or deprived of genius and creative spirit. But above all, they did not match the dominant features of the protest movement, on one side of which raged subjective vitalism and the most impulsive spontaneity and, on the other, gloomy and anti-aesthetic Stalinist political subjugation. All this explains why only a very few people actually received the SI's message: at the end of '68 only three people received the journal in Rome, and only 20 in Italy! Something of the high aesthetic qualities of the whole enterprise was transmitted to common readers who had the impression of belonging to a world revolutionary elite; indeed, they formed an international network within which it was possible to move not so much with a conspiratorial attitude as with an aristocraticone. In a form of historical blindness, however, the aesthetic feature of the Situationist endeavor was not recognized by either those who formulated it from within or by external observers. In a letter dated December 26, 1966, Guy Debord, in answer to some of my questions, summarized the SI projects in four points:

1. Theovercoming of life. This is meant to ofarttowardsa freeconstruction be the end of modem art,in whichDadaismwantedto suppressartwithout wanted to realizeart without suppressingit. realizingit, and Surrealism I am hereresumingtermsthatthe young (Thesetwo needs areinseparable, Marxused for the philosophy of his time). 2. Thecriticism that is to say,of modem society as concrete of thespectacle, lie, realization of an overturned world, ideological consumerism, concentratedand expanding alienation(finally:criticismof the modern stage of the worldly kingdom of the commodity). 3. Marx'srevolutionary theory- to be corrected and completed in the direction of its own radicalism (first of all, against all the heritage of

"Marxism") [...].

Substance # 90, 1999

An Aesthetic of the "GrandStyle" Style"

4. the modelof the revolutionary as target and Councils, powerof Workers' modelthatshouldalreadydominatethe revolutionary aiming organization at this [...]. The first two points are, in some ways, our main theoretical contribution. The thirdcomes fromrevolutionary theoryof the beginning of the historicalperiod to which we belong. The fourth comes from the of proletariansof this century. It is a question of revolutionarypractice unifyingthem.

93 93

What strikes me in this letteris the fact that the two most specific features of the SI are aesthetic, and that the idea of uniting tendencies and perspectives inscribed in different traditions is even more aesthetic. This corresponds exactly to a Nietzschean definition of "the grand style": "few principles and these hold very tightly together; no esprit,no rhetoric" (Nachgelassene, 1974, 3, 23). The Situationists' effort to maintain a certain distance from the world clashed inevitably with modern society's tendency to "recuperate" their revolt-that is to say, to neutralize it by assigning it a role and a function within society itself. Debord says in one of his films,

It is known that this society signs a sort of pact with its most avowed enemies, when it allots them a place in its spectacle.YetI am, indeed, at this time, the only personto have had some renown, clandestineand bad, and whom they have not managed to get to appear on this stage of renunciation[...].I would find it just as shabbyto become an authorityin the contestationof a society as to be one in this society itself. (Ingirum, 65-6)

It is not by chance that one of the most debated problems within the Situationist milieu concerned precisely its relationship with the cultural spectacle. In his letter of November 18,1967, notifying me of the publication of his book The Societyof the Spectacle, Debord writes:

Wecertainly all agree:"cinema" is in itselfa passivespectacular relationship [...].Theproblemis moregeneral:we believe thateven the book (a journal etc.) is also participatingin this separatemode of unilateralspectacular expression [...]. However, we believe that it is necessary to dominate criticallythese moments(theory,expression, agitation etc.) on different levels. It is evident for all of us thatwe cannotreduceourselves to a sort of pure immediacy.

On this last point Debord was too optimistic: spontaneity, vitalism, the myth of action were destined to be raging, especially in Italy,in the following years for at least a decade. These orientations, which refuse all mediation, nourish an infinite diffidence toward form, and aspire to an ideal of absolute transparencv

# 90, 1999 Substance

94

Pemiola Mario Perniola

represented the most serious problem of my youth. They were also present within the SI, especially in the circle of its sympathizers, but certainly they cannot be attributed to Debord, for whom every manifested alternative to writing "depends itself on a more or less complex consciousness and theoretical formulation" (Letter of March 2, 1968). This seems to contrast not only with the passions aroused by Debord, but also with the strongly emotional dimension of his writings and films, which seem often suspended between nostalgia and impassivity, between pain and hardness. The fact remains that next to the Apollonean Debord, whose essential feature is his distance from the world, there is a Dionysian Debord, about whom he made no mystery, and on whom he lingers in his memoirs when he celebrates various alcoholic drinks. The following seems revealing about the quality of such an experience: "First, like everyone, I appreciated the effect of slight drunkenness, then, very soon, I grew to like what lies beyond violent drunkenness when one has passed that stage: a magnificent and terrible peace, the true taste of the passage of time" (Panegyric 35). Or of time's suspension? What do these empirical, vital and even physiological aspects have to do with style? Doesn't style consist in leaving aside the subjective, the accidental, what it is too personal and too alive? Is not the Nietzschean notion of "the grand style" close to "classic" style? Certainly those features of hardening, simplification, reinforcementand turning nasty that for Nietzsche constitute the essential features of classical style are present in Debord. But "the grand style" is certainly something different from classicism, and from an aesthetic ideal of harmony and composure. As Heidegger observes, "the grand style" contains an element of excess, which the Greeks of the tragic age called deinon,deinotaton-the frightful. Thereforethe Nietzschean notion of "grand style" cannot be fully understood if it is separated from Nietzsche's reflection on the importance of the physiological component in art as an indispensable premise of style. In other words, style is separate from "the paralysis of form in what is dogmatic and formalistic, as [it is] from sheer rapturous tumult " (Nietzsche 128). With Nietzsche, an extreme aesthetic has been born. It goes beyond Kant and Hegel's moderate aesthetic, and in it feelings are followed to an extreme physiological state of the body. However, this does not mean succumbing to naturalism or to mere empirical factuality. In fact, "the grand style," according to Heidegger, is precisely a creative counter-movement in respect to the physiological. It presupposes its existence, but goes beyond it: "only what assimilates its sharpest antithesis, and not merely what holds that antithesis down and suppresses, is

Substance# 90, 1999

An Aesthetic of the "GrandStyle"

95

truly great; such transformation does not cause the antithesis to disappear, however, but to come to its essential unfolding"(Nietzsche135). An Aesthetic of Struggle One does not treat Debord fairly by considering him a pure theoretician: it is easy to put him into perspective by examining his writings exclusively from the point of view of their speculative originality. Indeed, more than theory, what counts for him is struggle; in his view, "theories are made only to die in the war of time: they are stronger or weaker units that must be engaged at the right moment in the combat [...];theories have to be replaced because their decisive victories even more than their partial defeats produce their wear-and-tear" (In girum, 25-6). It is possible to better understand his way of being by including him in a long tradition that dates back to the ancient philosopher Heraclitus, who believes that beauty is not harmony, but conflict. This strategic and energetic conception of beauty, in which aesthetics is not linked to the experience of conciliation (as in Pythagoras and in neoplatonism), but to that of war, resorts to the metaphors of lightning and fire. Beauty is considered as a weapon-in fact, as the strongest weapon. Hence the aesthetic dimension contains nothing decorative, or accessory or overstructural. It is tightly linked to the effectual, to reality, to a sphere that we usually regard as pertinent to politics. The Heraclitean conception, which operated underground in the Roman world through Stoicism, meets with the esthetic ideal supported by rhetoric and oratory,according to which the practical efficacy of the art of speech has an essential value. The sphere of beauty is therefore a battleground in which one wins or loses: it is the place of decision and result. According to Debord,

Individualswho do not act wish to believe that you can pick, freely, the excellenceof those who will figurein a combat,along with the place and time when you can strikean unstoppableand definitivehit. But no: with what is at hand, and accordingto the few effectivelyassailablepositions, you make a grab for one or the other as soon as a favorablemoment is apparent;otherwise you disappearwithout having achieved anything. (Ingirum 61)

This strategic conception of beauty was fully developed in the seventeenth century. The definition of beauty as sharpness, the comparison between the man of letters and the warrior, the mixture of aesthetic and political models make the Baroque a constant point of reference for Debord: in particular the figure of Baltasar Gracian deserves attention and respect.

# 90, 1999 Substance

96

Pemiola Mario Perniola

In his TheCourtier's ManualOracle,he was able to depict better than anyone else all the aspects of "the grand style" by rescuing it from any form of abstract classicism and immersing it in historical events and contingencies. However, even more than Gracian,it is the enemy of Richelieu and MazarinCardinalRetz-who occupies Debord's imagination. In his letter of December 24, 1968, Debord wrote to me:

I love the quotationof Retz'sMemoires not only because it touches upon the themes of the "imagination in power" and of "takeyour desires for but also because thereis a certainamusing relationshipbetween reality," the Frondeof 1648and May [1968]: the only two greatmovementsin Paris which exploded as immediateanswerto somearrests: and both with some barricades.

The subversive tradition in which Debord places himself is therefore more one of ancient-baroque tyrannicide than the modern one of political and social revolution: 1968 seems to him similar to the Fronde, not to the FrenchRevolution, much less the Russian Revolution. By comparing Debord to the Cardinal who animated the Fronde, there is in him a practice of truth that belongs to Retz the writer, but definitely not to Retz the man of action. It is easy, of course, to preserve one's integrity in solitude, or in a very restricted group of friends; it is a totally different matter to have to deal with all sorts of men and to fight in a civil war in which everybody knows that life itself is at stake! The "grand style" of Retz's Memoiresconsists above all in the distance he keeps from himself, in the unrestrained sincerity with which he exposes the most hidden motivations of his actions, even when it damages his reputation, but certainly it does not consist in the events that he tells! It is a post festum "grand style," so to speak, not in the flagrancy of action; in plotting intrigues, betrayals and conspiracies, Retz is no different from his enemies, and if his schemes have not succeeded, failurewas certainly unintentional and unwelcome! Debord's case is very different; in it the aesthetic of struggle, at least starting from the end of the 1960s, is shaped as an aesthetic of defeat, almost as if any success would contain an element of unavoidable vulgarity. Waris for him not only the realm of danger, but also of delusion (Panegyric, VI). I have always had a vague sense of the "obscure melancholy" that accompanied his life, as he acknowledged in In girium, and I saw the tragic and inevitable consequences of attributing to failure an aura of dismal splendor. What Debord has in common with Retz the writer is the questioning of what could have been and has not been. In his Mmoires, Retz often mentions events that were on the point of happening and did not happen for totally

# 90, 1999 Substance

An Aesthetic of the "GrandStyle"

97

accidental reasons. In his view, heroic judgment consists precisely in distinguishing the extraordinary from the impossible, in order to aim at the first and to avoid the second. In Debord as well there is a similar attitude: in his letter of June 10,1968 he writes to me: "Wehave almostmade a revolution. [...] The strike now has been defeated (mainly by the C.G.T.),but French society as a whole is in a crisis for a long period." Now, I wonder whether the "society of the spectacle" itself, erasing the distinction between true and false, between imagination and reality, has not also changed the notion of victory and defeat, freeing them from reference to the accomplished event and inaugurating a "society of simulacra." This is, however, a theoretical step that Debord never took; he remained fundamentally linked, like Retz, to a realistic vision of conflict. Maybe political thinkers of the sixteenth century (such as Machiavelli, Guicciardini and Loyola) had already moved beyond this vision. Debord's questioning the reasons for events, however, never becomes regret, much less repentance. He writes,

I have never quite understood the reproaches I have often incurred, whereby I lost this fine troopin a senseless assault,or with some sort of Neronian complacency.[...] I certainly [...] assume responsibilityfor all that happened"(Ingirum,60).

The stoic attitude of acceptance of present and past prevails: this is definitely a very important aspect of the "grand style." Life is a labyrinth from which there is no way out: from this, in fact, derives the title of his film In girum imus nocteet consumimur igni. This sentence, which means, literally, "Weturn around at night and we are devoured by fire,"presents the curious feature that one can read it from the last letter to the first without the slightest change-an extraordinary palindrome. Hence it expresses very well the the assent of the experience, typical of the ancient Stoics, of synkatathesis, wise to heimarmene, Providence, which they understood as the inviolable series of causes, "the rational law on the basis of which things that happened have happened, those that happen happen and those that will happen will happen" (Pohlenz). Connected to this experience is the stoic idea of the eternal return, that is to say, of the repetition of recurrentcosmic periods, in which the same events that have already occurred happen again. As is well-known, Nietzsche adopts the stoic conception of the eternal return and interprets it not as a metahistorical law but as "a will of eternal return," as amorfati:only in this way can the past stop being the cause of frustrationand powerlessness. The future will not be able to give us anything better than what the past has

Substance # 90, 1999

98

Pemiola Mario Perniola

already given us. The path of utopia is blocked for Nietzsche, as well as for Debord; it is extraneous to "the grand style." Debord says: "As for myself, I have never regretted anything I have done, and I admit that I am completely unable to imagine what else I could have done, by being what I am." (Panegyric47). The Direct Hold on History In Debord's way of being there is a last aspect that is probably more important than all the previous ones: the relationship with history. Indeed, his distance from the world and the aesthetic of conflict undoubtedly constitute style, but they do not make it really great. They can in fact lead to an ascetic model in which fanatical features are present: the figure of the warrior monk manifests a strong aesthetic dimension, for his courage and his (at first sight) contradictoryfeatures,but it is difficult to attributegrandeur to him. Something else is required;in Debord, this extra element comes from his relationship with the historical process, of which he claims to be not only the interpreter,but also an essential part. The SI believes in being the critical consciousness of the return of social revolution. Starting from the early 1960s, this expresses itself in unconscious and nascent forms in all industrial societies as the revolt of youth, racial uprisings, and struggles in the Third World. The social revolution is not conceived as an ideal to be realized, but, in Marx and Engels's words, as "the real movement that abolishes the existing state of affairs." During the period I was in contact with Debord, the boundless ambition to constitute the most advanced point of human progress (already present in Hegel and Marx) found some true support. For instance, the SI played a decisive role in the first European student revolt, in Strasbourg in Autunm 1966. While I was there, I had experienced the enthusiasm of feeling oneself in the avant-garde of a worldwide movement. But the highest point of the Situationist experience is represented by May 1968 in France. In fact this movement, exploiting the occasion of a student revolt, went a long way beyond the university environment, expanding to the industrial proletariat and to the whole of French society. In his letter of May 10, 1968 (2:00p.m.), in which Debord describes in detail the relationship between the SI and the student movement, and the events of May 3, May 6, and of that same morning, advising me to take some precautions with respect to the police, he affirms that "a decisive step has been made in the revolt and in the consciousness." And he adds,

Substance# 90, 1999

An Aesthetic of the "GrandStyle" Style"

The momentof the SI'sovercominghas not yet come:and this is why one needs to overcometheprevious stageof our action(if we were unableto do so, we would be "objectively"dissolved because the spreading of the struggle requiresthat a group such as the SI attaina correctand slightly more extended practice). In his letter of June 10, 1968, he writes: We had the opportunityto be at the heart of the entire event during the most interestingperiod.Wecontinueat the moment,but the futureis very uncertain.Wecount on the shockthatin many countriesopens the way to a international returnof the new revolutionary Herealreadytheory critique. had taken to the road. Everyold organizationhas bitterlyfought against the movement[...] The core people--including a certain number of workers-have been most of the time remarkable. Ourgroupwas formed 25 partisanswho joined in by 4 Situationists+ 2 Enrages+ approximately the battle (half of them were totally unknown before) [...] After having had the "Occupation Committeeof the Sorbonne"during the first days (one of them was decisive), we have formed the "Council for the of occupation" Maintenance which has had many contactsin Parisand in the provinces.

99

The Council, formed by Situationists, Enrages and sympathizers for a total of approximately 40 people, had functioned as an uninterruptedGeneral Assembly, deliberating day and night. It had three separate commissions in charge of compiling and printing documents, relations with occupied factories, and the supplies necessary for the activity.It published the "Report on the Occupation of the Sorbonne" (May 19), which exposed the events that had caused the failure of that experience;the declaration "Forthe Power of Workers' Councils" (May 22), which evaluated the possibility of reactivating certain sectors of the economy under workers' control; the "Appeal to All Workers"(May 30), which maintained that the movement in its reflux process "was missing only the consciousness of what it had already done, in order to really possess this revolution." With the State restoration in June, the Council dissolved, because it refused to have a permanent existence. While taking refuge in Brussels for fear of persecution (where I meet them in July 1968),the Situationistswrote the volume Enrages and Situationists in the Occupation Movement (signed Rene Vienet) and the article "The Beginning of an Era" (issue 12 of L'Internationale Situationniste),in which they perfected their judgement on May '68. In their opinion, the movement of May '68 was essentially proletarian and not a student one; it expressed itself on the occasion of a student revolt, but its development went farbeyond

Substance # 90, 1999

100

Mario Pemiola Perniola

the academic context: "The May movement was not some political theory looking for workers to carry it out; it was the acting proletariat seeking its theoretical consciousness" (Knabb,229). The fact that a small group of marginal intellectuals, poor and jobless, guided by a man who held the entire world "in gran dispitto,"had been at the heart of one the greatest spontaneous strikes in history, gave Debord extraordinary credibility and invested him with an almost prophetic role. Even in the moments of maximum enthusiasm during May, Debord kept an extraordinary lucidity of historical judgment. On May 15 he saw three possible developments in a decreasing order of probability: the spontaneous extinction of the movement, repression, and social revolution. On May 22 he deemed that the most probable solution to the crisis was the demobilization of workers, negotiated between Gaullism and the C.G.T.on the basis of economic advantages. In the conversations we had in July 1968 in Brussels, I was impressed by the fact that he considered a Russian invasion the most probable solution to the Czechoslovakian crisis, something that actually happened the following month, causing huge astonishment and scandal, above all in the milieu of the Left. I interpreted his silence on the historical events of the 1970s and 1980s as a negative judgment with respect to an age he would indeed define as "repugnant" (Panegyric,IV). But his "grand style" manifested itself once again with a masterly move: like TheSocietyof the Spectacle, published a year before '68, his Commentaries to the Societyof the Spectacle, which marked his return to great political theory, anticipated by some time the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet Union. This is how he renewed, for the years following 1989, his role as "occult master" of subversion. Two more brief considerations in the last pages of Panegyric seem prophetic to me. The first concerns the general hatred in which we are all immersed, because of the authoritarian redefinition of pleasures, both concerning their priority,and their substance. The second is even more subtle. Therefore I have to quote it in full:

It should be known that servitude henceforth truly wants to be loved for itself, and no longer because it would bring some extrinsic advantage. Previously, it could pass for protection; but it no longer protects anything.

Substance# 90, 1999

An Aestheticof of the the "Grand "Grand Style" An Aesthetic Style"

Servitudedoes not try to justifyitself now by claimingto have conserved, anywhere at all, a charm that would be anything other than the sole 77-8) pleasureof knowing it. (Panegyric

101 101

This seems to me the epigraph under which the present age stands. Universityof RomeII translatedby Olga Vasile

WORKS CITED

on theSociety Debord,Guy.Comments (1988).London:Verso,1990. of theSpectacle -. In girumimusnocteet consumimur igni. LondonPelagian Press, 1991a. (1989)London:Verso,1991b. Panegyric. . TheSociety Zone Books,1994. (1967).New York: of theSpectacle Heidegger,Martin.Nietzsche.(1961).San Francisco: Harper& Row, 1979. Pescara:Tracce,1992 (Englishtranslationby Donald NicholsonJappe,Anselm. Debord. UC Press, 1999). Smith,Berkeley: Nietzsche, FriederichTheGayScience. Random,1974. (1882).New York: Good andEvil (1886). New York: . Beyond VintageBooks, 1989. . Nachgelassene 1884-85.Berlin:De Gruyter, 1974. Fragmente -. Nachgelassene 1888-89.Berlin:De Gruyter, 1972. Fragmente In "Agaragar" n. 4. Rome:Arcana,1972.ReprintedRome: Perniola,Mario.I Situazionisti. Castelvecchi,1998. einergeistige Bewegung.Gottingen: Vandenhoek & Pohlenz, Max. Die Stoa. Geschichte Ruprecht,1959. Retz, Cardinalde. Memoires(1717).Paris:Gallimard,1983. International Bureauof Public Knabb,Ken,ed. and trans.Situationist Anthology.Berkeley: Secrets,1981. delsentire Vincentini,Isabella.Grande Stile,in L'aria sifa tesa.Perunafilosofia presente.Ed. MarioPerniola.Genoa:Costa & Nolan, 1994.

# 90, 1999 Substance

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Media Culture & the Triumph of the Spectacle: A HistoryDocument28 pagesMedia Culture & the Triumph of the Spectacle: A HistoryLilia ChuNo ratings yet

- Henri Lefebvre's The Production of SpaceDocument17 pagesHenri Lefebvre's The Production of SpaceaysenurozyerNo ratings yet

- University of Manitoba Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical JournalDocument17 pagesUniversity of Manitoba Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical JournalShikha KashyapNo ratings yet

- Historical Materialism 19.1 - Historical MaterialismDocument325 pagesHistorical Materialism 19.1 - Historical MaterialismTxavo Hesiaren100% (1)

- Bishop Critiques Spectacle and Participation in ArtDocument4 pagesBishop Critiques Spectacle and Participation in Artfai_iriNo ratings yet

- Critical Theories, Radical Pedagogies, and Social EducationDocument41 pagesCritical Theories, Radical Pedagogies, and Social EducationAndrew Romual67% (3)

- Strategies of CuratingDocument8 pagesStrategies of CuratingSara Alonso GómezNo ratings yet

- To Touch and Be Touched: Affective, Immersive and Critical Contemporary Art?Document11 pagesTo Touch and Be Touched: Affective, Immersive and Critical Contemporary Art?Mirtes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Franko Mark The Work of Dance Labor Movement and Identity in The 1930s PDFDocument110 pagesFranko Mark The Work of Dance Labor Movement and Identity in The 1930s PDFJavier Montero100% (2)

- The Ambiguity of Micro-UtopiasDocument8 pagesThe Ambiguity of Micro-UtopiaspolkleNo ratings yet

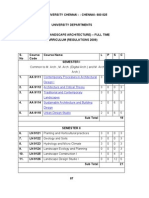

- M. Arch LandscapeDocument12 pagesM. Arch LandscapeSalma FathimaNo ratings yet

- Death in America Hal Foster PDFDocument25 pagesDeath in America Hal Foster PDFenriqueNo ratings yet

- Situationism in a NutshellDocument91 pagesSituationism in a NutshellNativeSonFLNo ratings yet

- Cesare Casarino, Three Theses On The Life-ImageDocument6 pagesCesare Casarino, Three Theses On The Life-ImageMarco AbelNo ratings yet

- To End With JudgementDocument7 pagesTo End With JudgementCláudia MüllerNo ratings yet

- Hollywood's Depiction of Arabs Post-9/11Document154 pagesHollywood's Depiction of Arabs Post-9/11الزبير محمدNo ratings yet

- Hatch With Cunliffe: Organization Theory, 3 Edition, Chapter 7Document5 pagesHatch With Cunliffe: Organization Theory, 3 Edition, Chapter 7BabarSirajNo ratings yet

- Debord, PanegyricDocument4 pagesDebord, PanegyricjczenkoanNo ratings yet

- From Wildcat Strikes to Total Self-ManagementDocument63 pagesFrom Wildcat Strikes to Total Self-ManagementKevin PinkertonNo ratings yet

- UCSPDocument46 pagesUCSPEva Mae TugbongNo ratings yet

- Women in Ukiyo-EDocument68 pagesWomen in Ukiyo-EtgmuscoNo ratings yet

- Resisting Postmodern Historical Vision in Don DeLillo's LibraDocument13 pagesResisting Postmodern Historical Vision in Don DeLillo's LibrathierryNo ratings yet

- Roundhouse JournalDocument76 pagesRoundhouse Journalanon_37622529No ratings yet

- The Spectacle 20 PDFDocument253 pagesThe Spectacle 20 PDFRegina Helena Alves Silva100% (1)

- Marilena Murariu, DESPRE ELENA ÎN GENERAL at Galeria SimezaDocument19 pagesMarilena Murariu, DESPRE ELENA ÎN GENERAL at Galeria SimezaModernismNo ratings yet

- Alexander J. Means, Derek R. Ford, Graham B. Slater (Eds.) - Educational Commons in Theory and Practice - Global Pedagogy and Politics (20Document278 pagesAlexander J. Means, Derek R. Ford, Graham B. Slater (Eds.) - Educational Commons in Theory and Practice - Global Pedagogy and Politics (20Manuel Alejandro Prada LondoñoNo ratings yet

- 161 FullDocument19 pages161 FullJo FagnerNo ratings yet

- Guy Debord Critique of SeparationDocument3 pagesGuy Debord Critique of SeparationjczenkoanNo ratings yet

- Zipes De-Disneyfying DisneyDocument8 pagesZipes De-Disneyfying DisneyFanni LeczkésiNo ratings yet

- Community Architecture Concept PDFDocument11 pagesCommunity Architecture Concept PDFdeanNo ratings yet