Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review Welding Procedures

Uploaded by

ippon_osotoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Welding Procedures

Uploaded by

ippon_osotoCopyright:

Available Formats

By Spencer O.

Luke

Feature

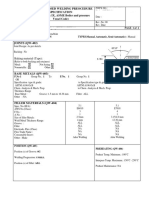

Reviewing Welding Procedures

Heres a look at some of the mistakes commonly found in Welding Procedure Specifications and how to avoid them

A competent review of welding procedures is an essential safeguard that can help ensure production welding (e.g., by the fabricator, contractor, subsuppliers, and erector) is in compliance with the requirements of the construction code and any additional requirements imposed by a contract specification and applicable industry standards. Imagine the consequences if any of the following occurred: Grade 91 (9Cr-1Mo-V) piping for critical steam service was welded with B3 consumables (2Cr-1Mo). Austenitic stainless steels for corrosive service were welded using plain carbon steel welding consumables. Piping or vessels for cryogenic service were welded with a welding procedure qualified without the required Charpy impact tests. Gas tungsten arc welding occurred using an argon/oxygen shielding gas mixture. ASME code work took place using AWS D1.1 welding procedures. These are just a few examples of glaring errors found during welding procedure reviews. The list of errors (and omissions) goes on and on from minor, inconsequential errors and typographical errors to major critical errors. Just because a Welding Procedure Specification (WPS) or Procedure Qualification Record (PQR) has been certified by the manufacturer or contractor as being in conformance

with code requirements, does not mean that is actually the case. In some instances, nothing could be further from the truth.

Common Mistakes

Experience after many years and reviews of thousands of welding procedures has shown there are a few common mistakes of which both writers and reviewers should be made aware. A large percentage of errors is due to the writer failing to do the following: Proofread the document Do a variable-by-variable code check Fail to ask him- or herself if the procedure makes good welding common sense. Most errors seem to be due to a lack of attention to detail, so heres a quick checklist that will help eliminate a lot of errors. Check the code. Check the contract. Check for special service requirements. Proofread. As with writing any formal document, its advisable to draft the procedure, walk away from it for a day or two or even longer when possible, and then come back to it again and review it for technical content and accuracy. Whenever possible, ask another competent individual to review the document. Also consider asking an experienced welder to look at the procedure.

A review by independent organizations or third-party insurers who have welding experts generally helps to ensure the documents are properly qualified, written, and certified.

Using Software to Write Procedures

Writing procedures using available welding procedure software programs does help ensure that all the required variables are properly addressed; however, the writer may still need to address any special items such as mandatory preheat or postweld heat treatment (PWHT) requirements, and special contract requirements. The person qualifying the procedure still needs to do so using appropriate filler metals and be knowledgeable enough to specify appropriate welding parameters. Before overriding any item within the software program, the user must know whether or not it will violate any code requirement. Its not uncommon to find an electronically produced WPS or PQR (such as created in MS Word or Excel) that was apparently created by modifying another electronic WPS or PQR. The writer duplicated the existing WPS or PQR in order to modify it and generate a new WPS or PQR; however, the person failed to update all the necessary fields. One of the most common errors of this type is where the filler metal on the new WPS

26

Inspection Trends / July 2013

or PQR was changed without updating the base material type (or vice versa). For example, a WPS might incorrectly indicate an E7018 electrode to weld an ASME P-No. 8 (stainless steel) base material. Mechanical test data on PQR forms are often inappropriately duplicated from one PQR to another. This same problem occurs when multiple references to the welding consumables are used on a WPS. For example, a WPS might indicate E7018 on the first page and E8018-B2 on the second page. Always check for multiple references to make sure the consumable classifications are consistent. Using a WPS or PQR form that specifies the consumable classification(s) in only one location on the form eliminates this type of error.

should be increased. When PQRs are corrected or amended, a notation and recertification signature should be added in order to document the correction or amendment. Particular attention should be made to the contractors document control procedures. The same errors identified and corrected on one contract sometimes resurface on submittals for a later contract.

The Review Process

Review of procedures is complicated when insufficient information is provided with the submittal. Its not uncommon to be asked to review a stack of procedures without being provided much other information. It is time consuming for the reviewer to track down contract specifications, materials of construction, identify any special service requirements or applicable industry standards, etc. For professional submittals, the submitter should consider at least developing a cover page that briefly describes the contract, materials of construction, any special requirements, and the assignment of the WPSs. While the review process should ultimately result in procedures that have been accepted, the shop or field CWI should verify the procedures are implemented properly; for example, verifying that the WPS is used only within its qualified limits. Occasionally a contractor will try to sneak through a WPS to weld on base materials the WPS is not qualified for, maybe with the thinking that the WPS is close enough. Fabrication codes generally require contractors or fabricators responsible for welding also to be responsible for qualifying their own welding procedures. In the end, the contractor or fabricator is also technically responsible for the content and accuracy of the welding documents. For reviewers who are not employed by the contractor or fabricator, the review comments should be worded so to avoid giving final approval of the welding documents, in which case the reviewer might be held responsible for

Beware of Outdated or Incomplete Forms

Using incorrect forms leads to errors. For example, if a form for the shielded metal arc welding (SMAW) process is used for the gas metal arc welding (GMAW) process, the writer can easily fail to address shielding gas since there isnt a data field for that variable. Errors occur when outdated or incomplete forms, without data fields for all the required code variables, are used. It is much easier to identify any missing information when proper up-to-date forms with all the necessary fields are used. Always use the latest code edition to qualify a welding procedure unless there is a specific reason to use an earlier edition. Often the code edition year listed on PQRs is a much earlier edition than was current at the time of qualification. Laboratories performing testing should also be requested to use and identify the latest code edition on the report forms. All the pages of a WPS should have the same identification number and the same revision level, and all pages of a PQR should have the same identification number. When WPSs are revised, the revision level

any consequences from oversights in review of the welding procedures. While a reviewer might not always check every variable in a welding procedure, the reviewer and especially the writer should be aware of possible consequences of any oversights. An authorized inspector, for example, might decide that welds produced with a noncompliant WPS needs to be cut out rather than accept the welds as a nonconformance. Verifying that welding procedures are properly qualified, meet contract requirements, and are properly implemented is serious business. In extreme instances, noncompliance can potentially result in loss of life, or rework costs and delays totaling hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars. Commonly, errors are attributed to the submitter or writer of the procedures failing to pay attention to the details of the contract or the particular service requirements. The writer, submitter, and reviewer should always have a basic checklist in mind regarding how welding procedures are written and qualified for the industry they serve. That checklist would vary from industry to industry. A mental checklist might include, for example, contract specification special requirements, specific code restrictions, NACE service, cryogenic service, seismic service, etc. Specific code restrictions might include, for example, mandatory preheat or PWHT requirements found in ASME B31.1. Writing and reviewing a welding procedure based on the base code welding requirements is usually a straightforward task. Making sure requirements of all associated relevant standards are addressed can require much more diligence. When writing a procedure, it is always advisable to use the appropriate code tables and references like a checklist in order to verify that all the necessary code variables have been addressed in the WPS and PQR.

How to Review Procedures

Following is a suggested methodology for reviewing procedures: Inspection Trends / Summer 2013

27

1. Use a common sense approach to identify errors. This step is a high-level review and can commonly be done even without a full variable check between the WPS and PQR. For example, are filler metals appropriate for the base materials being welded, are shielding gases or fluxes appropriate for the welding consumables being used, do welding parameters appear to be correct, is the electrical current and polarity correct, is this a material that requires preheat, is the information believable (for example, GMAW process using ER70S-6 with argon gas shielding recorded on both a PQR and WPS), is it accurate, etc. 2. Perform a detailed check. This step is a detailed check of all welding variables required by the code as well as requirements from other applicable standards. Examples of additional requirements include NACE hardness limitations, Charpy toughness, mandatory fabrication code preheat or PWHT, as well as special filler metal requirements.

Table 1 How to Specify Filler Metal Types ASME P-No. 8 Base Metal Type 304 304L 304H 316 316L 316H Adoption/use of standard AWS WPSs for work under ASME Section IX requirements (ASME IX, Article V): Failure of the contractor to perform and document a demonstration test required by ASME IX, Article V. 300 Series Stainless Steel: Failure to utilize a filler metal as corrosion resistant or as creep resistant as the base material. For example, Type 308 is commonly specified for welding Type 316 base materials. While 308 satisfies ASME Section IX qualification requirements, Type 308 fillers in many environments will not be as corrosion resistant as Type 316 base materials. Note that contractor procedures commonly indicate austenitic filler metals such as ER3xx, F-No. 6, A-No. 8 for welding ASME PNo. 8 base materials. For the reviewer, its not clear what base material type will be welded nor the specific filler metal AWS Classification that will be used. While this may be correct from an ASME Section IX perspective, a preferred, unambiguous way to specify the filler is also by AWS classification vs. actual base material type. For example, commonly assigned filler metals on a WPS could be listed as in Table 1. For welding of stainless steels and high-alloy materials, project specifications typically require purging during welding of single-pass, complete-joint-penetration welds. Welding procedures are commonly submitted, however, without amended requirements for purging. Miscellaneous: Failure to address mandatory code preheat requirements; e.g. ASME B31.1 mandates minimum preheat for some P-No. base materials. AWS Filler Metal Classification E/ER308 E/ER308L E/ER16-8-2 E/ER316 E/ER316L E/ER16-8-2 Utilizing the wrong code edition when specifying PWHT parameters. For procedures qualified for Charpy impact testing, specifying welding parameters that far exceed the allowable heat input range. Unless a welder has been trained to calculate and control heat input, a heat input limitation stated on the WPS may likely be exceeded during production welding without the appropriate welding parameters listed on the WPS. Failure to list the applicable code or testing standards on the PQR. AWS D1.1 Qualifications: Failure to perform or document the required visual examination or radiography examinations on the PQR test coupon. Failure to identify the specific weld joint details on qualified WPSs.

Examples of Common Errors

Following are some omissions/errors commonly identified during reviews. For the GMAW process: Failure to indicate the arc transfer mode (globular, short arc, spray). Where the transfer mode is indicated, parameters such as amps, volts, and wire feed speed will not produce the indicated arc transfer. Welding Positions: Failure to indicate uphill or downhill progression on the WPS or PQR. Interchanging qualification testing terminology on the PQR and WPS, e.g., using 1G, 2G, 3G, 4G, 6G on a WPS instead of F, H, V, OH. Procedure Qualification Tensile Testing: Failure to perform tensile testing in which the specimen(s) represents the full thickness of the PQR test coupon (reference ASME IX, QW-151.1).

28

Conclusion

While writing and reviewing WPSs and PQRs may seem confusing and to require too many steps at first, keep in mind that many common errors can be found simply by making a checklist, proofreading your work, and using some common sense.

SPENCER O. LUKE, P. E., (lukeso@bv.com) is an engineer, Black & Veatch, Overland Park, Kan. He is also an AWS CWI. One of his daily duties is to review welding procedures from companies around the world.

Inspection Trends / July 2013

You might also like

- DistortionDocument62 pagesDistortionManzar KhanNo ratings yet

- Butt JointsDocument21 pagesButt JointsRaj1-23No ratings yet

- Pipelines Welding HandbookDocument64 pagesPipelines Welding HandbookSixto GerardoNo ratings yet

- Heat Exchanger Inspection PDFDocument8 pagesHeat Exchanger Inspection PDFreezmanNo ratings yet

- Asme Sec Ix-WpqDocument47 pagesAsme Sec Ix-WpqKaushal Sojitra100% (1)

- ASME SECTION IX INTERPRETATIONSDocument95 pagesASME SECTION IX INTERPRETATIONSnizam1372No ratings yet

- Weldspec ASME PQRDocument2 pagesWeldspec ASME PQRSunil KumarNo ratings yet

- Uponor Montazni Manual EN FIN PDFDocument72 pagesUponor Montazni Manual EN FIN PDFAmar BayasgalanNo ratings yet

- ASME Impact Test RequirementDocument6 pagesASME Impact Test RequirementgaurangNo ratings yet

- Interpass Temperature WeldingDocument2 pagesInterpass Temperature Weldinghareesh13hNo ratings yet

- WPS, PQR, WQT, WPQ: BBW30103 Teknologi Kimpalan BerautomasiDocument12 pagesWPS, PQR, WQT, WPQ: BBW30103 Teknologi Kimpalan BerautomasiNazrin GLNo ratings yet

- Master Data Report YES (Check One) NO: Asme Boiler and Pressure Vessel CodeDocument2 pagesMaster Data Report YES (Check One) NO: Asme Boiler and Pressure Vessel CodeMuhammad Fitransyah Syamsuar Putra0% (1)

- NPCIL Tube Fitting SpecificationsDocument22 pagesNPCIL Tube Fitting Specificationssumant.c.singh1694100% (1)

- Thickness Qualification Range For PQR and WPQDocument5 pagesThickness Qualification Range For PQR and WPQOuled BladiNo ratings yet

- Asme Sec 9 - ADocument144 pagesAsme Sec 9 - Aروشان فاطمة روشانNo ratings yet

- QW 381Document1 pageQW 381Waqas WaqasNo ratings yet

- Asme 9 TipsDocument13 pagesAsme 9 TipsnasrpkNo ratings yet

- Welding Procedures and Welders QualificationDocument41 pagesWelding Procedures and Welders QualificationHamid MansouriNo ratings yet

- Addressing Some Issues in Drop Weight Testing - A Material Science ApproachDocument16 pagesAddressing Some Issues in Drop Weight Testing - A Material Science ApproachManish BhadauriaNo ratings yet

- PQR & WPQ Standard Testing Parameter WorksheetDocument4 pagesPQR & WPQ Standard Testing Parameter WorksheetcosmicbunnyNo ratings yet

- Weld RepairsDocument40 pagesWeld Repairsவிஷ்ணு ராஜசெல்வன்No ratings yet

- Welder Visual Inspection ReportsDocument24 pagesWelder Visual Inspection ReportsKyNo ratings yet

- Pressure Equipment Safety Authority Welding Exam Reference SyllabusDocument8 pagesPressure Equipment Safety Authority Welding Exam Reference SyllabusSiva Sankara Narayanan SubramanianNo ratings yet

- Piping WPS SMAWDocument2 pagesPiping WPS SMAWJk KarthikNo ratings yet

- Welding Repair Procedure for JG Summit ProjectDocument12 pagesWelding Repair Procedure for JG Summit ProjectDarrel Espino AranasNo ratings yet

- WELDING PROCEDURE SPECIFICATION FOR TANK TK 5109/5110/5111Document15 pagesWELDING PROCEDURE SPECIFICATION FOR TANK TK 5109/5110/5111surya1960No ratings yet

- Brazing Procedure 1Document5 pagesBrazing Procedure 1Tina MillerNo ratings yet

- NDT As Per B31.3Document2 pagesNDT As Per B31.3invilink87No ratings yet

- API Welding ProcedureDocument2 pagesAPI Welding ProcedureSamarakoon BandaNo ratings yet

- 0301e - Guidebook For Inspectors - 2018-3Document6 pages0301e - Guidebook For Inspectors - 2018-3FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Ingenieria de La Soldadura PDFDocument11 pagesIngenieria de La Soldadura PDFedscesc10100% (1)

- BPQ REV. 0 Interactive FormDocument2 pagesBPQ REV. 0 Interactive FormcosmicbunnyNo ratings yet

- How To Specify and Predict Ferrite Number in Stainless Steel WeldsDocument11 pagesHow To Specify and Predict Ferrite Number in Stainless Steel WeldsWeldPulseNo ratings yet

- Sense & Nonsense of Welding Procedure QualificationDocument25 pagesSense & Nonsense of Welding Procedure QualificationamdidgurNo ratings yet

- WPS and PQR ChecklistDocument2 pagesWPS and PQR Checklistshabbir626No ratings yet

- I Can Do That WPS'S, PQR's and WQ'sDocument93 pagesI Can Do That WPS'S, PQR's and WQ'sKo NSNo ratings yet

- ASME-Sec-IX, WPS, Quick Guide To Fix-Essential & Non-Essential VariablesDocument9 pagesASME-Sec-IX, WPS, Quick Guide To Fix-Essential & Non-Essential VariablesAnnamalai Ram JGC100% (2)

- SAIC-M-2012 Rev 7supportsDocument33 pagesSAIC-M-2012 Rev 7supportsvijayachiduNo ratings yet

- Linde Rates For Welding Test Services-2018Document2 pagesLinde Rates For Welding Test Services-2018Hoque AnamulNo ratings yet

- Deviations During PWHT and ResponseDocument2 pagesDeviations During PWHT and ResponseEIL NDT100% (1)

- WPS& WQRDocument132 pagesWPS& WQRAby Jacob Mathews100% (3)

- CSWIP 3.1 - Welding Inspection-WIS5-2006 PDFDocument358 pagesCSWIP 3.1 - Welding Inspection-WIS5-2006 PDFTuan DangNo ratings yet

- Lesson 14 WelderQuals - New2Document80 pagesLesson 14 WelderQuals - New2Mohd Syafiq100% (1)

- 2G & 5GDocument2 pages2G & 5GRahul MoottolikandyNo ratings yet

- ASME Welding PositionsDocument3 pagesASME Welding PositionsMicheal MurphyNo ratings yet

- WPS-2 InchDocument2 pagesWPS-2 InchKarthikeyan MpNo ratings yet

- TighteningofStructuralBolts 31-35Document5 pagesTighteningofStructuralBolts 31-35masaud akhtarNo ratings yet

- Weld Log - 5000 WeldDocument234 pagesWeld Log - 5000 WeldRichard MitchellNo ratings yet

- Understanding WPS, PQR, WPQRDocument4 pagesUnderstanding WPS, PQR, WPQRYousef Adel HassanenNo ratings yet

- Reapir and Altertaion Section 8Document52 pagesReapir and Altertaion Section 8waqas pirachaNo ratings yet

- D1.5M D1.5 2015 AMD1 Form O 2 FillableDocument1 pageD1.5M D1.5 2015 AMD1 Form O 2 Fillablevikasphopale1No ratings yet

- ISO 15614 vs ASME IX welding standards comparisonDocument2 pagesISO 15614 vs ASME IX welding standards comparisontuanNo ratings yet

- Welder Qualification (ALL CODES)Document3 pagesWelder Qualification (ALL CODES)narutothunderjet216No ratings yet

- Introducion To Codes Standards and SpecificationsDocument16 pagesIntroducion To Codes Standards and SpecificationsmohamedqcNo ratings yet

- Visual Inspection Workshop2Document42 pagesVisual Inspection Workshop2saeedsaeed31100% (2)

- Documents Guiding Welding InspectionDocument11 pagesDocuments Guiding Welding InspectionZaheed ManooNo ratings yet

- Dutyies of Welding InspectorDocument30 pagesDutyies of Welding InspectorMorg Actus100% (1)

- Importance of Welding SoftwareDocument3 pagesImportance of Welding SoftwareAshfaq AnwerNo ratings yet

- GEneral Welding System RequirementsDocument6 pagesGEneral Welding System Requirementsvominhthai100% (1)

- What Every Steel Erector Should Know About Welding RequirementsDocument6 pagesWhat Every Steel Erector Should Know About Welding RequirementsrinuakNo ratings yet

- Pages From AWS-WHB Vol1 9th-EdDocument1 pagePages From AWS-WHB Vol1 9th-Edippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Transisi Iso 2001 TH 2008 Ke 2015 PDFDocument32 pagesTransisi Iso 2001 TH 2008 Ke 2015 PDFsellen34No ratings yet

- Sample Arc StrikeDocument1 pageSample Arc Strikeippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Safe PracticesDocument1 pageSafe Practicesippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- CQI Quality Management CertificatesDocument2 pagesCQI Quality Management Certificatesippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Iosh Ms DatasheetDocument3 pagesIosh Ms Datasheetippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Wi Application FormDocument2 pagesWi Application Formippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Pages From AWS-WHB Vol1 9th-EdDocument1 pagePages From AWS-WHB Vol1 9th-Edippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Continuing Professional Development: Steps of CPDDocument1 pageContinuing Professional Development: Steps of CPDippon_osoto100% (1)

- FibersparDocument2 pagesFibersparippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Cqi Certificate in Quality Management: Frequently Asked Questions (Faqs) ForDocument4 pagesCqi Certificate in Quality Management: Frequently Asked Questions (Faqs) Forippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Sample ExamDocument2 pagesSample Examippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- BPVC IX Interp STND 63 2014 JulDocument4 pagesBPVC IX Interp STND 63 2014 Julprasanth4747No ratings yet

- BSI Training Academy Quality Management Systems DiplomaDocument2 pagesBSI Training Academy Quality Management Systems Diplomaippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Information Sheet CQI StudentsDocument4 pagesInformation Sheet CQI Studentsippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- CQE Fact SheetDocument2 pagesCQE Fact Sheetippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- FibersparDocument2 pagesFibersparippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- PMP Sample Test Questions (Correct Answers Are Bolded)Document1 pagePMP Sample Test Questions (Correct Answers Are Bolded)CKJJ55@hotmail.cmNo ratings yet

- Sample API 1104 WpsDocument1 pageSample API 1104 Wpsippon_osoto100% (1)

- Presure Testing GuidanceDocument15 pagesPresure Testing GuidanceMahmood EijazNo ratings yet

- Verbal Judo: The Gentle Art of PersuasionDocument33 pagesVerbal Judo: The Gentle Art of PersuasionmadmaxpsuNo ratings yet

- Presure Testing GuidanceDocument15 pagesPresure Testing GuidanceMahmood EijazNo ratings yet

- Purgeye Api100 LFT A3-Web-PDocument4 pagesPurgeye Api100 LFT A3-Web-Pippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Pages From ASME - B31.4-2016Document1 pagePages From ASME - B31.4-2016ippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- AIA Philam Life Policy Fund Withdrawal FormDocument2 pagesAIA Philam Life Policy Fund Withdrawal Formippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Pages From SAES W 012Document1 pagePages From SAES W 012ippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- AIA Philam Life Request For Extension of Grace PeriodDocument1 pageAIA Philam Life Request For Extension of Grace Periodippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Climb Central Manila RegistrationDocument1 pageClimb Central Manila Registrationippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- PEMI - Redemption Order Form (ROF)Document1 pagePEMI - Redemption Order Form (ROF)ippon_osotoNo ratings yet

- Weld Cracking PDFDocument5 pagesWeld Cracking PDFjuanNo ratings yet

- Yontomo Sukses Abadi: Mig Gun Set & PartsDocument2 pagesYontomo Sukses Abadi: Mig Gun Set & PartsnoviNo ratings yet

- Gate Solved Paper - Me: Manufacturing EngineeringDocument72 pagesGate Solved Paper - Me: Manufacturing EngineeringVHemendra NaiduNo ratings yet

- Corner JointDocument2 pagesCorner JointTayyab HussainNo ratings yet

- AlloysDocument91 pagesAlloysNiccoloNo ratings yet

- Weldwell's Guide to Welding ElectrodesDocument96 pagesWeldwell's Guide to Welding ElectrodesRodolfoMarínNo ratings yet

- Prolyte StructuresDocument100 pagesProlyte StructuresdsosicNo ratings yet

- Product Advantages: This Product Has A Number of Unique CharacteristicsDocument1 pageProduct Advantages: This Product Has A Number of Unique CharacteristicsAnkita AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Level Gages PenberthyDocument34 pagesLevel Gages PenberthySrta IncognitaNo ratings yet

- Esab Buddy TIG400iDocument2 pagesEsab Buddy TIG400iJeganeswaranNo ratings yet

- ESAB 453ccDocument32 pagesESAB 453ccdavid bolivarNo ratings yet

- In Plant Industrial Training Undertaken atDocument47 pagesIn Plant Industrial Training Undertaken atyttftfiugiuiuNo ratings yet

- Joint Welding Method PHC D600A-100Document2 pagesJoint Welding Method PHC D600A-100sochealaoNo ratings yet

- Hyundai Wheel Loader HL770-7 - Service Manual - Operators Manual - Wiring DiagramsDocument1,065 pagesHyundai Wheel Loader HL770-7 - Service Manual - Operators Manual - Wiring DiagramsRui ArezesNo ratings yet

- 5a100t PDFDocument254 pages5a100t PDFHenrique50% (2)

- BHELDocument12 pagesBHELShanmukh KatariNo ratings yet

- IACS Requirement For MooringDocument21 pagesIACS Requirement For Mooringantonalmeida100% (2)

- Unifrax Engineered Thermal Components Application StoryDocument2 pagesUnifrax Engineered Thermal Components Application StoryAjin SNo ratings yet

- DE-930525 Rev 5Document36 pagesDE-930525 Rev 5Shemeer SainudeenNo ratings yet

- ASME2019 KeyChangesSectionIDocument8 pagesASME2019 KeyChangesSectionIمحمد نعمان بٹNo ratings yet

- UPP Installation Manual - V7a - WebDocument124 pagesUPP Installation Manual - V7a - WebFranco TorrealbaNo ratings yet

- Work Method Statement: Activity Wms For Mivan Modification WorkDocument6 pagesWork Method Statement: Activity Wms For Mivan Modification WorkamolNo ratings yet

- PSK GET 9th v2Document827 pagesPSK GET 9th v2Luis PozoNo ratings yet

- 1 - CBT Welding NDT 26 02 2020 - Ans and ExplanetionDocument27 pages1 - CBT Welding NDT 26 02 2020 - Ans and ExplanetionAMALENDU PAULNo ratings yet

- Tapco Catalog 6th EditionDocument108 pagesTapco Catalog 6th EditionchinhvuvanNo ratings yet

- Cadweld CatalogoDocument123 pagesCadweld CatalogoRaul Gerardo SilvaNo ratings yet

- Who TRS 970 Anexo 2 PDFDocument23 pagesWho TRS 970 Anexo 2 PDFAnonymous guhSjjNWdP100% (1)

- Research and Development of Heat Resistant Materials For Advanced - 2015 - EnginDocument14 pagesResearch and Development of Heat Resistant Materials For Advanced - 2015 - EnginDicky Pratama PutraNo ratings yet

- Get Parts Caterpillar PDFDocument1,398 pagesGet Parts Caterpillar PDFMarco BacianNo ratings yet

- PIPE and TubesDocument11 pagesPIPE and TubesnamNo ratings yet

- Learn Python Programming for Beginners: Best Step-by-Step Guide for Coding with Python, Great for Kids and Adults. Includes Practical Exercises on Data Analysis, Machine Learning and More.From EverandLearn Python Programming for Beginners: Best Step-by-Step Guide for Coding with Python, Great for Kids and Adults. Includes Practical Exercises on Data Analysis, Machine Learning and More.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- Software Engineering at Google: Lessons Learned from Programming Over TimeFrom EverandSoftware Engineering at Google: Lessons Learned from Programming Over TimeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of ComputingFrom EverandWhat Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of ComputingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (41)

- Introducing Python: Modern Computing in Simple Packages, 2nd EditionFrom EverandIntroducing Python: Modern Computing in Simple Packages, 2nd EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- The Advanced Roblox Coding Book: An Unofficial Guide, Updated Edition: Learn How to Script Games, Code Objects and Settings, and Create Your Own World!From EverandThe Advanced Roblox Coding Book: An Unofficial Guide, Updated Edition: Learn How to Script Games, Code Objects and Settings, and Create Your Own World!Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Excel Essentials: A Step-by-Step Guide with Pictures for Absolute Beginners to Master the Basics and Start Using Excel with ConfidenceFrom EverandExcel Essentials: A Step-by-Step Guide with Pictures for Absolute Beginners to Master the Basics and Start Using Excel with ConfidenceNo ratings yet

- Nine Algorithms That Changed the Future: The Ingenious Ideas That Drive Today's ComputersFrom EverandNine Algorithms That Changed the Future: The Ingenious Ideas That Drive Today's ComputersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Linux: The Ultimate Beginner's Guide to Learn Linux Operating System, Command Line and Linux Programming Step by StepFrom EverandLinux: The Ultimate Beginner's Guide to Learn Linux Operating System, Command Line and Linux Programming Step by StepRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Generative Art: A practical guide using ProcessingFrom EverandGenerative Art: A practical guide using ProcessingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Unit Testing Principles, Practices, and PatternsFrom EverandUnit Testing Principles, Practices, and PatternsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software CraftsmanshipFrom EverandClean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software CraftsmanshipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (13)

- Python Programming : How to Code Python Fast In Just 24 Hours With 7 Simple StepsFrom EverandPython Programming : How to Code Python Fast In Just 24 Hours With 7 Simple StepsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (54)

- CODING FOR ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS: How to Keep Your Data Safe from Hackers by Mastering the Basic Functions of Python, Java, and C++ (2022 Guide for Newbies)From EverandCODING FOR ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS: How to Keep Your Data Safe from Hackers by Mastering the Basic Functions of Python, Java, and C++ (2022 Guide for Newbies)No ratings yet

- GROKKING ALGORITHMS: Simple and Effective Methods to Grokking Deep Learning and Machine LearningFrom EverandGROKKING ALGORITHMS: Simple and Effective Methods to Grokking Deep Learning and Machine LearningNo ratings yet

- Python: For Beginners A Crash Course Guide To Learn Python in 1 WeekFrom EverandPython: For Beginners A Crash Course Guide To Learn Python in 1 WeekRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (23)

- Excel 2016: A Comprehensive Beginner’s Guide to Microsoft Excel 2016From EverandExcel 2016: A Comprehensive Beginner’s Guide to Microsoft Excel 2016Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Data Analytics with Python: Data Analytics in Python Using PandasFrom EverandData Analytics with Python: Data Analytics in Python Using PandasRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)