Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Self Objectification, Body Shame and Eating Disorders

Uploaded by

arhodes777Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Self Objectification, Body Shame and Eating Disorders

Uploaded by

arhodes777Copyright:

Available Formats

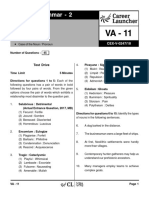

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

U5a1 Research Paper Project: Sociocultural Influences on Self Objectification and Body Shame Anthony Rhodes Capella University

2911 Hamilton Blvd. 444 Sioux City, Iowa 51104 Telephone: 712-301-9258 Email: anthonyrhodes54@yahoo.com Instructor: Dr. Gloria Fisher, PhD. Abstract

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

Self objectification was defined as internalizing sociocultural norms and interpersonal experiences of the female body as an object to be used. This paper examined the relationship of body shame as a mediating factor between self objectification and eating disorder symptomatology. It further analyzed the assumption that body image discrepancies represent a mediating factor in relationship to self objectification and body shame. Moderating roles of self esteem and neuroticism were explored in relationship to body image discrepancies and body shame. Body image discrepancy was shown to as a mediator between self objectification and body shame and as a significant mediator that requires further research to assist in minimizing the effects of objectification theory in women.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

Table of Contents Abstract Introduction Objectification Theory Self Objectification and Related Concepts Self objectification and Body Dissatisfaction Self Objectification and Self Monitoring Correlation between Self Objectification and Body Shame Self esteem Neuroticism Discussion References 2 4 8 9 9 10 12 15 17 18 21

Introduction The concern for dieting and controlling weight is a normative experience for many girls and women living in the United States. Much of the body of literature on the subject suggests

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

that across the life span women experience more concern for weight and appearance than do men (Peat, Peyerl & Muehlenkamp, 2008). There is little doubt that Western women are subject to a great deal of pressure to conform to the thin ideal of feminine beauty. The thin ideal is perpetuated and reinforced by a number of sociocultural influences. Probably the most pervasive and powerful are the influences of mass media. Immersed in the popular culture of today, women are subject to stereotypes about expectations that idealize thinness resulting in debilitating obsessions and anxiety over physical appearances. One content analysis of 69 American women magazines revealed that 94% displayed an image of a thin-idealized model or celebrity on the cover (Malkin, Wornian & Chrisler, 1999). By choosing to promote thinness as the desired norm over various representative body types in society, the implicit message is that deviation from the thin ideal is abnormal. Meta-analysis of experimental research concluded that women who viewed images of thin models consistently reported poorer body image outcomes than participants who viewed images of average weight models, plus size models, or neutral figures (Groesz, Levine & Mumen, 2002). A meta-analytic study showed that there is a small to moderate positive correlation between level of exposure to mass media such as TV and magazines and body dissatisfaction, self objectification, body shame and disordered eating (Tiggemann, Polivy, & Hargreaves, 2009). Moreover, women who find enjoyment and pleasure in beauty and fashion magazines may internalize an increasingly unrealistic thin ideal for themselves and increase their risk of body image and eating pathology.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

According to Kassin, Fein, & Markus (2008), college women with high self-ideal or body image discrepancies were more likely to make comparisons to thin models which also increased their body dissatisfaction, pathological depression and vulnerability to eating disorders. It was found that the tendency to make comparisons in response to idealized thin images of female beauty was related to both internalization and body dissatisfaction (Tiggemann, 2005). According to Hospers and Jansen (as cited in Tiggemann, 2005), meta-analysis of longitudinal studies identifies body dissatisfaction as one of the most consistent and robust risk factors for eating pathology among women. Boisvert & Harrell (2009) determined homosexuality is a risk factor for eating disorders in males. The study findings support empirical research showing that compared to heterosexual men, gay men are at greater risk for eating disorder symptomatology. It showed that homosexual men were thinner, scored higher on body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptomatology, lower on self-esteem and masculinity, and reported more peer pressure. Peer pressure, reflecting the higher value placed upon physical attractiveness, slenderness and muscularity within the gay culture, had a more pronounced effect on body dissatisfaction for gay men. Although the health risks associated with restricting food intake for women are high, among gay men, this behavior could be even more dangerous if they engage in unhealthy eating practices, steroid use, or excessive exercise to stay muscular and slim; these are linked to body image and eating problems. Furthermore, some researchers have associated eating disorders, body dissatisfaction, and obesity with suicidal behavior in adolescents as well (CDC, 2009). The association of obesity and suicidal behavior in adolescents would represent a significant public health concern, given

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

the marked increases in the prevalence of obesity among adolescents in the United States. Comorbid conditions in which body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, or obesity is predictive of the occurrence of suicidal behaviors or suicidal ideation is not fully known and further research is imperative. Nevertheless, obesity appears related to both body dissatisfaction and body shame. Triggerman and Lynch (2001) reported that body shame is positively related to body dissatisfaction which is predominantly robust across the life span as well. The medias impact is an important concern for those individuals who are prone to high levels of body self monitoring, as well those who are susceptible to sociocultural norms regarding body image and self esteem. According to Triggerman and Lynch (2001) the critical importance of body image does not differ across young, middle age and older women. Strong correlating evidence suggests that there is a link between self objectification, body dissatisfaction and body shame. Body image and body dissatisfaction are critical aspects of ones self concept that have been shown to contribute to eating disorders (Peat, Peyerl & Muehlenkamp, 2008). These types of stereotypes when internalized often give rise to serious eating disorders such as bulimia (food binges and purging) and anorexia nervosa (a form of self starvation). The desire for thinness is one of the most important criterions for diagnosing eating disorders. Furthermore, rates for these maladaptive behaviors are higher than the average among female college students than nonstudents (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2008). This study is designed to further examine the correlation between self objectification, body shame, body discrepancies and maladaptive behaviors in women. Objectification Theory

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

While the growing body of evidence sheds light on the potentially dangerous role that the media plays in contributing to womens body image and dissatisfaction, there is a need to identify psychological mechanisms that influence them. Objectification theory asserts that women are uniquely subject to sociocultural norms and experiences in which the female body is evaluated and treated as an object to be used by others (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). This type of sexual objectification experience can socialize women to internalize a third party perspective of their body image. This process, termed self objectification, can exist in two dimensions as an emotional state as well as a personality trait. The extent to which women internalize a third party perspective is a determining factor of trait self objectification. In contrast, state self objectification is believed to fluctuate over time and increase according to factors that produce an increase in self monitoring (Tiggemann & Lynch 2001). Differences in culture, ethnicity, age, sexuality, personal experiences and physical attributes may cause levels of self objectification to vary. Self objectification frequently occurs when the female body is sexually evaluated in some way through personal interactive encounters as well as through the media. Morry and Staska (2001) found a significant correlation between exposure to fashion and beauty magazines and trait objectification. Through these encounters women are led to feel and believe that their bodies are to be used as objects. Perceived experiences of self objectification over time may cause individuals to consider it more important to emphasize how one looks rather than other qualities. This is caused by the tendency to engage in frequent episodes of self monitoring or surveillance. A host of negative

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

experiences correlate with high trait self objectification such as appearance anxiety, body shame, decreased intrinsic motivation and self efficacy, eating disorders, and depression (Tiggemann & Lynch 2001). Self Objectification and Related Concepts Self Objectification and Body Dissatisfaction It is important to note that distinguishing between self objectification and other related concepts helps to identify correlating factors among mediating, dependent and independent variables. The concept of body dissatisfaction may appear somewhat similar but it is distinct by definition and relationship to self objectification. Noteworthy is the fact that a woman who is self objectifying is focused on the physical self but is not necessarily dissatisfied with the appearance of her body. It is body dissatisfaction that contends that one is inherently dissatisfied and discontent with her body. However, self objectification and body dissatisfaction can be correlating factors. Because beauty ideals in most cases are not attainable, self objectification and body dissatisfaction will be closely related. However, self objectification has more widespread effects than body dissatisfaction. It has been argued that when individuals are focused on the physical self from a third party perspective, cognitive abilities can be impaired resulting in a reduced ability to focus on other tasks (Tiggemann & Lynch, 2001). However, even if women are consistently satisfied with their bodies they may still experience the adverse effects of self objectification through the internalization of sociocultural norms regarding thin ideals. Self Objectification and Self Monitoring

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

Self monitoring is the tendency to change behavior to meet the demands or responses to the self presentation concerns of the sociocultural milieu (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2008). Those who are high in self monitoring are particularly sensitive to social and interpersonal cues that may cause him or her to alter behavior and expression to meet sociocultural demands. Individuals low in self monitoring, tend to be self verifiers and are not concerned with altering their behavior but prefer others to view them as they really are. In contrast, high self monitoring individuals will often go to great lengths to adhere to conformity standards dictated by the sociocultural milieu. High self monitors are highly attuned to their inner dispositions and are overly concerned about what other people think of them. Self monitoring and self objectification overlap conceptually as the two concepts involve a concern for another perspective regarding self. However, the difference between the two concepts is also significant. Self monitoring unlike self objectification is not concerned with adopting another perspective on the physical self. Individuals who are high in self objectification have internalized an observers perspective on the physical self which involves the broader perspective of internalizing ideals and attitudes. Taking ownership of idealized thin images presented in sociocultural contexts is often the result of experiences of sexual objectification or the perspective of the female body as a sex object. Self monitoring does not necessarily involve the notion of internalization but involves a heightened sensitivity about adjusting his or her behavior to fit the situational context. A self monitoring individual manages impressions and uses self presentation strategies to present the desired self.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

10

In terms of outward appearances in general, the behavioral expression of the social self is maintained through the act of self presentation. This is a process by which people employ strategies to shape what others think of them (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2008). Strategic self presentations utilize various self effort strategies through the process of self monitoring to shape others impressions to gain influence, power, sympathy, or approval. Therefore, although self monitoring does not include the process of internalizing standards, sociocultural norms and perception data it could be considered a correlating variable in objectification theory. Correlation between Self Objectification and Body Shame Consistent and severe self monitoring of the body that results from self objectification is related to a number of cognitive and emotional consequences that present may activate the physical and mental health risks mentioned above. The varied consequences of self objectification lead primarily to negative health outcomes. Relevant to this present study is the theoretical relation of self objectification and body shame. Self objectification increases ones vulnerability to experience shame about ones body. According to Merriam-Websters Online Dictionary (Shame, 2009), shame is a painful emotion caused by the consciousness of guilt, shortcoming, or impropriety. It is this kind of emotion that may cause a person to want to disappear or even die. Shame can occur when individuals evaluate themselves in relation to an internalized standard and realize they have failed to meet that standard. Standards and norms are often acquired over time through sociocultural environments and interpersonal experiences. Shame has a motivating component that can also cause individuals to make adjustments and alterations in the self that are inconsistent with internalized sociocultural standards and norms.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

11

Research has indicated that trait and state objectification is positively related to body shame even after maintaining control for Body Mass Index (BMI) which measures overweight and obesity in relationship to height (Calogero, Davis, & Thompson, 2005). It was also found that body shame partially mediated between trait self objectification and various indicators of disorder eating attitudes and behaviors such as the drive for thinness, anorexia and symptoms of bulimia (Calogero, Davis, & Thompson, 2005). Body shame is initiated when women internalize anothers view of their physical self. Body shame appears to be the emotional component of self objectification when women feel the bombardment from media images of beautiful and thin female body images and/or the sense of perceiving themselves as sexual objects as well. Frederick and Roberts (1997) postulate that individuals with body shame are likely to compare themselves to unrealistic standards. Therefore, the comparison of ones actual body and the ideal occurs when self objectification is triggered and consequently produces body shame. Even when women are not overweight they may feel the sense of shame about their bodies because they do not measure up to the ideal standard that is frequently presented and admired in society. However, it is possible for a woman, although highly engaged in self monitoring, to not experience body shame. It is important to note however that these women may experience a theorized component of body shame but avoid the emotional component through extreme disordered (e.g. anorexia) eating thus feeling a temporary and elated sense of normality. A woman may also feel a sense of shame about her body but not feel objectified as a result of adopting an ideal third party perspective. However, studies indicate that in most cases, a woman will feel a sense of body shame as a result of self objectification (Frederick and Roberts, 1997).

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

12

Further analysis indicates that body shame is a function of body image discrepancies regarding how one feels about her body and the internalized objectified ideal. This gives rise to the theory that body image discrepancies can be a mediating factor between body shame and self objectification. Feelings of embarrassment and shame can result from the internal conflict that exists within an individual when the ideal and actual physical self are examined and analyzed. A more complete picture of the pathway to disordered eating may result from the understanding that body image discrepancies are mediating factors between self objectification and body shame (Tiggemann, 2005). This is an extremely important area of investigation for mental health practitioners. These findings can assist in helping to assess risk factors from disordered eating symptomatology in regards to mediating factors of body image discrepancies. Self Esteem Self esteem can be defined as an affective component of the self, consisting of a persons positive and negative self evaluations (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2008). The desire for self esteem is often driven by the primitive need to connect with others and gain their approval. Intimately connected with the concept of self esteem is the need to actualize the sense of self worth. People derive a sense of self worth from their appearance; physical strength, professional accomplishments, wealth, people skills or group affiliations. High self esteem acts as a protective shield that promotes mental health and adaptive social behaviors. Positive or negative self evaluations or self esteem is often defined by the body discrepancies of how people see themselves and how others see them. However, Timmerman (2005) indicated that the reduction of body discrepancy in high self-esteem subjects

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

13

demonstrated an assimilation effect, with higher body satisfaction after upward than downward comparison to media images of thin models. This provides another example of a possible inspirational or thinness fantasy effect for some women regardless of the mechanism of body discrepancies. Additional research indicates that fantasy instructions led participants to feel good in general (positive mood), but not about their body in particular (body dissatisfaction) (Tiggemann, Polivy, & Hargreaves, 2009). Furthermore, individuals who hold body image discrepancies but have high self esteem feel less shame about their bodies and conversely those who have low esteem and body discrepancies will possess higher feeling of body shame. If women are high in self objectification but possess a high self esteem, it seems likely that they will experience a reduction in body shame, even if they have a discrepancy between their actual and ideal body type.

Neuroticism Research indicates that differences in mental health and well being are related to dispositional characteristics (Smith & MacKenzie, 2006). Neuroticism is a trait characteristic that is a measure of emotional instability and related to negative emotional states. Highly neurotic individuals are said to experience feelings of nervousness, tension, worry, irritability, vulnerability, anger and sadness. Furthermore, neuroticism is often associated with more negative appraisals of self, depression and high levels of self monitoring.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

14

Therefore neuroticism may be a moderator between body image discrepancies and body shame. It is possible that when a person scores high in neuroticism and perceive a body discrepancy between the ideal and actual self she will also experience a greater level of body shame. A woman may be more susceptible to body shame if she is highly neurotic and has a body image discrepancy that strongly recognizes a difference between how she looks and how she feels she should look. Neuroticism is often seen as a trait that exists in comorbidity with other characteristics to influence the expression of psychopathologies (e.g. Claridge & Davis, 2001). Therefore it seems reasonable to assume that neuroticism is a mediating factor in body discrepancies and body shame. Discussion Based upon the above research, body image discrepancies appear to be a mediating factor between self objectification and body shame (Tiggemann, 2005). Furthermore, there is research evidence that highlights the consideration that chronic body image discrepancies play an important part in the development of body shame and maladaptive eating attitudes and behaviors (Levine & Murnen, 2009). Research on self objectification theory from body related discrepancies has also yielded associations between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating (Tiggemann, 2005). Additional research is needed to further confirm these findings. There were a number of gaps in the standardized samples of the research data considered, analyzed and evaluated in this research project. The research on self objectification did not consider the role of ethnicity, gender, age, the full spectrum of sexual orientation, the wider range of eating disorders and socioeconomic status.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

15

Objectification theory may yield increased understanding of the causes and potential treatment options related to obesity and weight gain in individuals as well. Feelings of body shame in the case of obese individuals may lead to a sense of hopelessness. This may translate into the practices that represent another end of the eating disorder spectrum of related overweight and obesity conditions through binge eating. Furthermore, additional research on objectification in men may yield significant understanding of the pressure to achieve a physical ideal in the same way as women. Clearly, further testing and research is warranted to confirm these findings and associations in various populations. It is clear from the research findings that one of the ways in which one can counter the effects of self objectification is to focus on the variable of body image discrepancies (Tiggemann, 2005, Boisvert & Harrell, 2009). It may be extremely difficult for women or gay males to avoid perceived experiences of self objectification. However, it is possible to reduce the body image discrepancies held by individuals by highlighting the unattainable nature of idealized body standards used in comparisons to actual body image. Reducing feelings of body shame can be initiated through the use of school education programs and adjustments in media images and campaigns. Companies that use a more accurate portrayal of a broader spectrum of body shapes and sizes in advertising can contribute by playing a key role in reducing body shame and subsequently curtailing the onslaught of associated eating disorders. Real world marketing campaigns that challenge the beauty myths of our time and portray a more accurate image of the average American woman should be commended and recognized for their affective contribution to promoting mental health.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

16

There is also the need for a more holistic look at innovative treatment options that involve mind and body exercises like yoga to reduce body image discrepancies, body shame and self objectification. A recent study showed a positive linear relationship between body esteem and psychological well-being through the use of yoga techniques and meditation (Kelly, 2009). This offers the opportunity of overcoming the prevailing sociocultural norms of female body image and objectification through meditation and yoga which emphasizes a holistic approach to understanding self. The field of health psychology would benefit from treatment strategies which enhance optimal wellness through holistic treatment options that deliver higher self esteem levels and resources needed to allow women to experience feelings, aspirations and self awareness free of unrealistic beauty ideals.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

17

References Boisvert, J., & Harrell, W.. (2009). Homosexuality as a risk factor for eating disorder symptomatology in men. Journal of Men's Studies, 17(3), 210-225. Retrieved December 11, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1897246051). Calogero, R. M., Davis, W. N., & Thompson, J. K. (2005). The role of self objectification in the experience of women with eating disorders. Sex Roles, 52, 43-59. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Atlanta, GA. Retrieved on December 10, 2009 From http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/index.html Claridge, G & Davis, C. (2001). Whats the use of neuroticism? Personality & Individual Differences, 31, 383-400. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591). Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding womens of womens lived experiences and mental health risks, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173-206. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591). Groesz, L. M., Levine, M. P., & Mumen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytical review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 1-16. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591).

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

18

Kassin, S. Fein, S. & Markus, H. (2008). Social psychology (7th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN: 9780618989966. Kelly, J. L. (2009). Body esteem and psychological well-being in female yoga practitioners (Doctoral dissertation). Available from Proquest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3356495) Levine, M., & Murnen, S.. (2009). "Everybody knows that mass media are/are not [pick one] a cause of eating disorders": A critical review of evidence for a causal link between media, negative body image, and disordered eating in females. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(1), 9-42. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. Malkin, A. R., Wornier, K., & Chrisler, J. C. (1999). Women and weight: gendered messages on magazine covers. Sex roles, 40, 647-656. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591). Morry, M. M., & Staska, S. L. (2001). Magazine exposure: internalization, self-objectification, eating attitudes, and body satisfaction in male and female university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 33, 269-279. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591). Peat, C., Peyerl, N., & Muehlenkamp, J.. (2008). Body image and eating disorders in older adults: A review. The Journal of General Psychology, 135(4), 343-58. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ABI/INFORM Global. Shame. (2009). In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary.

Running Head: u5a1 CURRENT EVENT

19

Retrieved December 11, 2009, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/shame Smith, T. W., & MacKenzie, J. (2006). Personality and risk of physical illness. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 435-467. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591). Tiggemann, M. (2005). The state of body image research in clinical and social psychology. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(8), 1202-1210. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 977588801). Tiggemann, M., & Lynch, J. (2001). Body image across the life span in adult women: The role of self-objectification. Developmental Psychology, 37, 243-253. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591). Tiggemann, M., Polivy, J., & Hargreaves, D.. (2009). The processing of thin ideals in fashion magazines: A source of social comparison or fantasy? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(1), 73-93. Retrieved December 10, 2009, from ProQuest Psychology Journals. (Document ID: 1642953591).

You might also like

- Body ImageDocument3 pagesBody Imagepragatigupta14No ratings yet

- Sociology of Sport Chapter 1Document23 pagesSociology of Sport Chapter 1Fakhrul A RahmanNo ratings yet

- Wood Eagly Handbook 2010 PDFDocument39 pagesWood Eagly Handbook 2010 PDFSusana BrigasNo ratings yet

- PRARE Gender RolesDocument8 pagesPRARE Gender RolesBelle HonaNo ratings yet

- How personality and music type affect concentration: A comparison of classical and hip hop musicDocument14 pagesHow personality and music type affect concentration: A comparison of classical and hip hop musicnabila dayaniNo ratings yet

- SSQ Validation StudyDocument18 pagesSSQ Validation StudyCoco MaciNo ratings yet

- Chapter01 ReviewDocument27 pagesChapter01 ReviewEf Abdul0% (1)

- Skinny Is Not Enough A Content Analysis of Fitspiration On PinterestDocument9 pagesSkinny Is Not Enough A Content Analysis of Fitspiration On PinterestFOLKLORE BRECHÓNo ratings yet

- Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic PerspectiveDocument3 pagesSocial Cognitive Theory: An Agentic PerspectiveHope Rogen TiongcoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Women Gender Sexuality StudiesDocument133 pagesIntroduction To Women Gender Sexuality StudiesM.IMRANNo ratings yet

- Gender Representation in Ukrainian TV CommercialsDocument8 pagesGender Representation in Ukrainian TV CommercialsAnonymous pDZgYSNo ratings yet

- What Is Science in Anthropology?Document5 pagesWhat Is Science in Anthropology?ArannoHossainNo ratings yet

- Jewish and DurkheimDocument22 pagesJewish and DurkheimAl AlyaNo ratings yet

- Glee As A Pop-Culture ReflectionDocument47 pagesGlee As A Pop-Culture ReflectionNew English SkyNo ratings yet

- Body Image and The Media FinalDocument11 pagesBody Image and The Media Finalapi-429760816100% (2)

- Social Comparison and The Idealized Standards of AdvertisingDocument14 pagesSocial Comparison and The Idealized Standards of AdvertisingRaveNo ratings yet

- Redefining Roles: The Professional, Faculty, and Graduate Consultant’s Guide to Writing CentersFrom EverandRedefining Roles: The Professional, Faculty, and Graduate Consultant’s Guide to Writing CentersMegan Swihart JewellNo ratings yet

- 10 Page Essay WFCDocument12 pages10 Page Essay WFCapi-344557725No ratings yet

- (Amy Best) Representing Youth Methodological Issu (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFDocument353 pages(Amy Best) Representing Youth Methodological Issu (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFFelipe SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Bussey, Bandura. Social Cognitive Theory of Gender Dev and DiffDocument38 pagesBussey, Bandura. Social Cognitive Theory of Gender Dev and DiffKateřina Capoušková100% (2)

- Anthropology Rediscovers Sexuality-A Theoretical Comment PDFDocument10 pagesAnthropology Rediscovers Sexuality-A Theoretical Comment PDFHeyy8No ratings yet

- Cognitive Psychology SAQ Essay QuestionDocument5 pagesCognitive Psychology SAQ Essay QuestionPhoebe XieNo ratings yet

- BookDocument499 pagesBookapi-3813809100% (1)

- The Effects of Gender Role Socialization On Self-Expression of Female Students in Secondary School The Case of Fasil-DeseDocument10 pagesThe Effects of Gender Role Socialization On Self-Expression of Female Students in Secondary School The Case of Fasil-DesearcherselevatorsNo ratings yet

- Apa Final PaperDocument17 pagesApa Final Paperapi-499652905No ratings yet

- I and Thou and World? A Critical Analysis of Buberian SocialismDocument13 pagesI and Thou and World? A Critical Analysis of Buberian Socialismalim4No ratings yet

- Feminist Ways of Knowing and MethodologyDocument25 pagesFeminist Ways of Knowing and MethodologyjeremiezulaskiNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Gender in Early YearsDocument21 pagesPerceptions of Gender in Early YearsJ WestNo ratings yet

- Toxic Masculinty and Homophobia ProposalDocument12 pagesToxic Masculinty and Homophobia ProposalKara WaltersdorffNo ratings yet

- Bandura A. (2004)Document23 pagesBandura A. (2004)crpanaNo ratings yet

- A Conception of Adult DevelopmentDocument11 pagesA Conception of Adult DevelopmentJosue Claudio DantasNo ratings yet

- Subliminal PerceptionDocument9 pagesSubliminal PerceptiontmmtNo ratings yet

- Understanding PsychologyDocument5 pagesUnderstanding PsychologyKibria UtshobNo ratings yet

- Multiple Exposure To Appearance Focused Real Accounts On Instagram Effects On Body Image Among Both GendersDocument10 pagesMultiple Exposure To Appearance Focused Real Accounts On Instagram Effects On Body Image Among Both GendersghgjhNo ratings yet

- Cultural Capital - Elliot B WeiningerDocument5 pagesCultural Capital - Elliot B Weiningerapi-102693643No ratings yet

- The Brain's Default Network: Anatomy, Function, and Relevance To DiseaseDocument38 pagesThe Brain's Default Network: Anatomy, Function, and Relevance To DiseaseMarkoff ChaneyNo ratings yet

- Walker 1989Document28 pagesWalker 1989Joaquín Edgardo Reyes RomeroNo ratings yet

- Through A Student' S Psyche: Retracing Stereotype and PrejudiceDocument32 pagesThrough A Student' S Psyche: Retracing Stereotype and PrejudiceJoseph Mary MercadoNo ratings yet

- Operant Conditioning Edward ThorndikeDocument5 pagesOperant Conditioning Edward ThorndikeSajid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Tok Presentation Arts StereotypesDocument5 pagesTok Presentation Arts StereotypesLa ReinaNo ratings yet

- Women in AdvertisingDocument9 pagesWomen in Advertisingapi-465344430No ratings yet

- Albert Bandura:: Social Cognitive TheoryDocument12 pagesAlbert Bandura:: Social Cognitive TheoryGabby Man EENo ratings yet

- Rachel Karrer Research Paper EngDocument7 pagesRachel Karrer Research Paper Engapi-242079438No ratings yet

- Aro Village SystemDocument5 pagesAro Village SystemObehi EromoseleNo ratings yet

- Gender Stereotyping of Women in Contemporary Magazine Advertisements by Pariya Sripakdeevong (Will) (M.I.T. Psychology of Gender and Race)Document26 pagesGender Stereotyping of Women in Contemporary Magazine Advertisements by Pariya Sripakdeevong (Will) (M.I.T. Psychology of Gender and Race)weillyNo ratings yet

- Represntation SemioticsDocument24 pagesRepresntation SemioticsDivya RavichandranNo ratings yet

- Queer Theory Group 5Document16 pagesQueer Theory Group 5Joshua Gabriel QuizonNo ratings yet

- Human Agency in Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1989)Document10 pagesHuman Agency in Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1989)Pickle_Pumpkin100% (1)

- Adolescent Romantic Relationships and Delinquency InvolvementDocument34 pagesAdolescent Romantic Relationships and Delinquency Involvementklr1835No ratings yet

- The Problem and Its Setting Background of The StudyDocument20 pagesThe Problem and Its Setting Background of The StudyDimple ElpmidNo ratings yet

- Eating Disorders and Sociocultural InfluencesDocument15 pagesEating Disorders and Sociocultural InfluencesNana YotinwatcharaNo ratings yet

- Blowers Et AlDocument16 pagesBlowers Et Alnanamixx100% (1)

- Pluralistic Ignorance, Social Comparison, and Body SatisfactionDocument46 pagesPluralistic Ignorance, Social Comparison, and Body SatisfactionNikka LaborteNo ratings yet

- Theories On Eating Disorders and Its Correlations With Certain Personality TraitsDocument7 pagesTheories On Eating Disorders and Its Correlations With Certain Personality TraitsBlack LettuceNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 KIMDocument2 pagesChapter 2 KIMKatrina FernandezNo ratings yet

- Society's Influence and Perception of Body Image and Appearance 1Document12 pagesSociety's Influence and Perception of Body Image and Appearance 1clrgrillotNo ratings yet

- Eating DisorderDocument18 pagesEating DisordernNo ratings yet

- Bodyimageinthecontextof Eatingdisorders: Siân A. Mclean,, Susan J. PaxtonDocument12 pagesBodyimageinthecontextof Eatingdisorders: Siân A. Mclean,, Susan J. PaxtonStrejaru TeodoraNo ratings yet

- Being Highly SensitiveDocument3 pagesBeing Highly Sensitivearhodes777No ratings yet

- CaseStudy 3 PaperDocument9 pagesCaseStudy 3 Paperarhodes777No ratings yet

- CaseStudy 1 PaperDocument8 pagesCaseStudy 1 Paperarhodes777No ratings yet

- APA Website Journals by SubjectDocument2 pagesAPA Website Journals by Subjectarhodes777No ratings yet

- Psychosocial Risk Factors For Future Adolescent Suicide AttemptsDocument18 pagesPsychosocial Risk Factors For Future Adolescent Suicide Attemptsarhodes777No ratings yet

- CaseStudy 2 PaperDocument9 pagesCaseStudy 2 Paperarhodes777No ratings yet

- App Holster LLC Financial AnalysisDocument7 pagesApp Holster LLC Financial AnalysisHAMMADHRNo ratings yet

- Collective Unconscious: Transpersonal InterpersonalDocument1 pageCollective Unconscious: Transpersonal Interpersonalarhodes777No ratings yet

- Critical Literature ReviewDocument26 pagesCritical Literature Reviewarhodes777No ratings yet

- Psy 7411 U04d2 Information Processing M-SR ModelDocument1 pagePsy 7411 U04d2 Information Processing M-SR Modelarhodes777No ratings yet

- Critical Literature ReviewDocument26 pagesCritical Literature Reviewarhodes777No ratings yet

- Adolescent Suicide Myths in The United StatesDocument14 pagesAdolescent Suicide Myths in The United Statesarhodes777No ratings yet

- Unit 9 - Discriminant Analysis Theory and LogicDocument2 pagesUnit 9 - Discriminant Analysis Theory and Logicarhodes777No ratings yet

- U07a1 Literature Evaluation PaperDocument11 pagesU07a1 Literature Evaluation Paperarhodes777100% (1)

- Common Risk Factors in Adolescent Suicide Attempters RevisitedDocument11 pagesCommon Risk Factors in Adolescent Suicide Attempters Revisitedarhodes777No ratings yet

- U08d2 Creativity: Response GuidelinesDocument5 pagesU08d2 Creativity: Response Guidelinesarhodes777No ratings yet

- Empirical Support For An Evolutionary Model of SelfDocument15 pagesEmpirical Support For An Evolutionary Model of Selfarhodes777No ratings yet

- An Examination of Training Model Outcomes in Clinical Psychology Programs - HighlightedDocument14 pagesAn Examination of Training Model Outcomes in Clinical Psychology Programs - Highlightedarhodes777No ratings yet

- Unit 5 - Logistic Regression - Theory and LogicDocument2 pagesUnit 5 - Logistic Regression - Theory and Logicarhodes777No ratings yet

- U03a1 Practitioner-Scholar PaperDocument5 pagesU03a1 Practitioner-Scholar Paperarhodes777No ratings yet

- U09d2 Classification in Discriminant AnalysisDocument2 pagesU09d2 Classification in Discriminant Analysisarhodes777No ratings yet

- U03a1 Practitioner-Scholar PaperDocument5 pagesU03a1 Practitioner-Scholar Paperarhodes777No ratings yet

- Logistic Regression Theory & MethodsDocument2 pagesLogistic Regression Theory & Methodsarhodes777No ratings yet

- U05d2 Types of Logistic RegressionDocument2 pagesU05d2 Types of Logistic Regressionarhodes777No ratings yet

- U05d2 Types of Logistic RegressionDocument2 pagesU05d2 Types of Logistic Regressionarhodes777No ratings yet

- U06d2 An Integrated Theory of The MindDocument3 pagesU06d2 An Integrated Theory of The Mindarhodes777No ratings yet

- U05d1 Interpretation of OddsDocument2 pagesU05d1 Interpretation of Oddsarhodes777No ratings yet

- Nature vs Nurture Debate in Language AcquisitionDocument4 pagesNature vs Nurture Debate in Language Acquisitionarhodes777No ratings yet

- U08d1 The Development of ExpertiseDocument3 pagesU08d1 The Development of Expertisearhodes777No ratings yet

- U07d2 Language and The Human ExperienceDocument3 pagesU07d2 Language and The Human Experiencearhodes777100% (1)

- Personal Development ReviewerDocument1 pagePersonal Development Reviewergoboj12957No ratings yet

- Relationship Between Personality Factors and Level of Forgiveness Among College StudentsDocument16 pagesRelationship Between Personality Factors and Level of Forgiveness Among College StudentsGenela RamirezNo ratings yet

- The Short-Form Revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ-S)Document9 pagesThe Short-Form Revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ-S)nesumaNo ratings yet

- BprsDocument7 pagesBprsamyljf100% (1)

- Online Rules and Regulations: QR-ACA-CAE04-002Document51 pagesOnline Rules and Regulations: QR-ACA-CAE04-002Loren Marie Lemana AceboNo ratings yet

- The Hand Test FinalDocument22 pagesThe Hand Test Finaltaylor alison swiftNo ratings yet

- The Nonlinear Association Between Grandiose and Vulnerable NarcissismDocument14 pagesThe Nonlinear Association Between Grandiose and Vulnerable NarcissismTing Hin WongNo ratings yet

- IPIP-NEO ReportDocument7 pagesIPIP-NEO ReportTommy JengaNo ratings yet

- Childhood Abuse Affects Family Ties Later in LifeDocument12 pagesChildhood Abuse Affects Family Ties Later in LifeNurul rizki IsnaeniNo ratings yet

- Understand Myself - The Big Five Aspects ScaleDocument15 pagesUnderstand Myself - The Big Five Aspects ScaleRaphael LimaNo ratings yet

- BPIDocument40 pagesBPILara Patricia TamsiNo ratings yet

- The Role of Extraversion in Phishing Victimisation A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesThe Role of Extraversion in Phishing Victimisation A Systematic Literature ReviewTourjana SuptiNo ratings yet

- The Big Five Personality TheoryDocument20 pagesThe Big Five Personality TheoryCtmanis Nyer100% (1)

- Human Relations Interpersonal Job Oriented Skills Canadian 4th Edition DuBrin Geerinck 013310530X Test BankDocument6 pagesHuman Relations Interpersonal Job Oriented Skills Canadian 4th Edition DuBrin Geerinck 013310530X Test Bankrose100% (21)

- MODULE COMPILATION in EED 15Document76 pagesMODULE COMPILATION in EED 15Carla Angela AngwasNo ratings yet

- Personality Traits (1617289345)Document232 pagesPersonality Traits (1617289345)Ana Ivanova Tamakarova100% (5)

- Chapter 14 EysenckDocument7 pagesChapter 14 EysenckBeatriz RoaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Childhood Psychological TraumaDocument23 pagesEffect of Childhood Psychological TraumaSea SaltNo ratings yet

- VA-11 Grammar 2 With SolutionsDocument9 pagesVA-11 Grammar 2 With SolutionsSOURAV LOHIANo ratings yet

- Theories of Personality 849KB PDFDocument208 pagesTheories of Personality 849KB PDFCha GuillermoNo ratings yet

- StateData Code BookDocument2 pagesStateData Code BookeshobhaNo ratings yet

- Trait Reappraisal Predicts Affective Reactivity To Daily Positive and Negative EventsDocument9 pagesTrait Reappraisal Predicts Affective Reactivity To Daily Positive and Negative EventsGulNo ratings yet

- UNIT 3 Personality JohariDocument15 pagesUNIT 3 Personality Joharipullarao kotaNo ratings yet

- Women Online Shopping: A Critical Review of Literature: SSRN Electronic Journal January 2014Document10 pagesWomen Online Shopping: A Critical Review of Literature: SSRN Electronic Journal January 2014Rémàñ RáçérNo ratings yet

- Ob Unit 2Document34 pagesOb Unit 2Dr umamaheswari.sNo ratings yet

- Individual Difference Personality Traits and Gender Personality TraitsDocument2 pagesIndividual Difference Personality Traits and Gender Personality TraitsSaad MajeedNo ratings yet

- DAPT InterpretationDocument18 pagesDAPT InterpretationSAMANTHA LACABANo ratings yet

- COMM 151 Organizational BehaviourDocument61 pagesCOMM 151 Organizational BehaviourKanak NageeNo ratings yet

- Icid Short VersionDocument6 pagesIcid Short VersionJelena DebeljakNo ratings yet

- Rachel Yehuda Cortisol PTSD Policía BomberosDocument14 pagesRachel Yehuda Cortisol PTSD Policía BomberosPaulo GermanottaNo ratings yet