Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Coetzee's Estrangement

Uploaded by

dekonstrukcijaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Coetzee's Estrangement

Uploaded by

dekonstrukcijaCopyright:

Available Formats

1 Coetzees Estrangement

David Attwell University of York

Now that it is over and done with, that life-time labour of writing, she is capable of casting a glance back over it that is cool enough, she believes, even cold enough, not to be deceived. Her books teach nothing, preach nothing; they merely spell out, as clearly as they can, how people lived in a certain time and place. (Elizabeth Costello 207)

Seen from the outside as a historical specimen, I am a late representative of the vast movement of European expansion that took place from the sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth century of the Christian era, a movement that more or less achieved its purpose of conquest and settlement in the Americas and Australasia, but failed totally in Asia and almost totally in Africa. I say that I represent this movement because my intellectual allegiances are clearly European, not African. I am also a representative of the generation in South Africa for whom apartheid was created, the generation that was meant to benefit most from it. What the correct relationship ought to be between a representative of this failed or failing colonial movement, with this history of oppression behind it, on the one hand, and the part of the world where it sought and failed to establish itself and the people of that part of the world on the other hand, is the subject of your question . My response, a dubious and hesitant one, is that it has been and may continue to be, in the time that is left to me, more productive to live out the question than to try to answer it in abstract terms. When I say I have lived out the question I mean I have lived it out not only in day to day life but in my fiction as well. (Interview, Dagens Nyeter 7 December, 2003.)

Ill begin with J.M. Coetzees Slow Man which, despite being the first of Coetzees fictions to be set wholly in Australia, carries the marks of the authors formation in South Africa. In is a prejudicial preposition, however, because I will argue in fact that this formation came about because of Coetzees estrangement from the country. In reading estrangement, I will rely on Nancy Ruttenbergs recent brilliant analysis of Fyodor Dostoevskys fictionalised memoir based on his prison experience, Notes from the House of the Dead. Estrangement is understood both in terms of place and of aesthetics, both positionality and representation. By place I do not refer to those places of Coetzees and South African fiction in general that are the subject of much critical discussion: the farm, the segregated township, or more recently, the globalized city. I mean something closer to the nation-state the way the signifier South Africa figures in Age of Iron. Nearly all of Coetzees fiction deals in one way or another with subjects who reluctantly find themselves forced to engage with a particular historical situation, and there should be no mystery about where this emphasis comes from: it comes from Coetzees own sense of having South Africanness in various forms (as a legal structure of citizenship, an historical identity, as well as the cultural edifice of being a South African writer) forced upon him. A consistent premise of Coetzees writing is that one does not choose ones history; it chooses you. A given historical situation is a bounded horizon

3 within which one exercises restricted options and longs to be able to exercise others. The source of this emphasis is partly biographical: as his memoir Youth suggests, Coetzee was on the path of emigration soon after the Sharpeville massacre and its consequences. By the late 1960s (a period not covered by the memoir) he would have succeeded, had it not been for the legal constraint of being unable to achieve permanent residence in the United States. His return to South Africa was precipitous; thereafter, South Africa, both in its own peculiarities and as the site of a world-historical denouement of European colonial modernity, became the primary historical condition with which Coetzee would find himself wrestling. Each gesture of fictive displacement, or each act of imaginative relocation, speaks of this effort in his writing to keep the country at arms length. Michael Ks efforts to remain free and unobserved in a landscape that has been completely mapped, fenced and policed, is representative of a general condition affecting Coetzees authorship especially when we consider, as several critics have done, the possibility that K himself allegorizes the practice of writing. This situation helps to explain the tripartite architecture that surfaces in much of Coetzees fiction: the subject (frequently a subject living in a body, often a body in pain, marked by the contending social forces, a body from which the subject feels alienated); history (as a field of contestations, of torsions of power, in Coetzees phrase, in which the subject never feels at home); and language (as a field of representations which are subject to processes of cultural obsolescence and renewal) This architecture is both persistent and elemental, and what it lacks in social density it gains in intensity and a capacity to speak paradigmatically of late European colonialism, or of the post-

4 enlightenment subject encountering heterogeneity and difference in a previously unimagined and radical sense. Slow Man continues with this pattern. It deals with bodily frailty and fears of senescence and obsolescence. The blow catches him from the right, sharp and surprising and painful, like a bolt of electricity, lifting him up off the bicycle (1). The words are simple but their catastrophic implications define the course of the narrative, dividing Paul Rayments life into two phases, a relatively unexamined phase even, as he puts it, of frivolousness before the accident, and the phase of the narratives present tense, in which because of his vulnerabilities he will discover how deeply he is at odds with the culture in which he lives. His discoveries turn on the subject of care in a world defined both by the corporatization of what are misleadingly called the caring professions, and by transnational and transcultural migrations and their effects on families. The accident, then, leads us directly to the architecture I mentioned earlier: the subject, rendered in characteristically bodily terms; and history, which the subject encounters in a state of shock (and lets not forget the first words of Dusklands, my name is Eugene Dawn. I cannot help that. Here goes.). This history, then, smashes into the subject, in this case in the form of the car driven by the reckless Wayne Blight. Finally, language, language which Rayment does not own, because it comes to him in a state which is already culturally marked for the worse: he flies through the air with the greatest of ease, he thinks, and Like a cat roll, then spring to your feet, ready for what comes next (1), fragments of language that are completely inappropriate to the dire situation he is in. The intrusion of such inappropriate discourse raises the question of what residues of culture can be salvaged from over-use if we are to survive the history

5 which is forced upon us. The novels milieu might be Adelaide but the basic narrative situation and its inherent tensions will be familiar to many of Coetzees readers. Not that the subjects place in history is rendered terms of sweeping, epic narrative; it is presented in spaces of intense intimacy. After inappropriately confessing his love for his Croatian nurse Marijana, he anticipates a response from her which he has learned from the romantic novels his mother used to receive by mail-order from the Librairie Hachette in Paris: If there ever was which he doubts a code of looks that once mastered would allow one to read infallibly the transient motions of human lips and eyes, it has gone now, gone with the wind (77). In order to decode desire, it seems, one needs to be in possession of the right code; such codes are the products of culture and therefore historical; as such they drift into obsolescence; if we apply them anachronistically we become even more detached from our objects of desire than we normally are, leaving us with only the silent spaces between us. Finding the right code in situations of ethnographic or linguistic alterity might be doubly difficult. The final phrases of the quotation, gone now, gone with the wind, suggest redundancy of a romantic American, antebellum kind which is comic in its inappropriateness. If obsolescence is ones lot, irony might be a form of survival: Paul doubts the existence of the code that would enable him to read Marijana infallibly. Ironic self-protection as a way of surviving obsolescence: Coetzees memoirs, especially Youth, play out this solution repeatedly. Paul Rayment experiences the present as a time of thinning out, of moral and cultural impoverishment. The language of his carers is appallingly demeaning. His collection of photographs by Fauchery expresses a desire for representations of Australia

6 that have weight, distinction and pathos, and he resists digital technology which lacks these qualities. His attraction to Marijana is based in part on the fact that she comes from a corner of an old Europe which with his French childhood and his Catholicism, he imagines he has some affinity. Her slow adjustment to Australian speech is part of what makes her attractive; like her, he speaks English like a foreigner, phlegmatically, with due deliberation. He does not have a ready language of the heart and must intuit things, leaving him vulnerable to fantasy and wish-fulfilment. A more centred cultural existence would give him better resources for dealing with his physical precariousness and his longings. In all these dimensions, the exploration of Paul Rayments condition is a finely tuned historical diagnosis which plays out the architecture of subject-history-language with which I began. Then, of course, there is Elizabeth Costello. What is she doing in this novel? The novel which seems closest to Slow Man, in this respect, is Foe, where Susan Barton crafts a narrative of her experience on the island with Crusoe and Friday, then hands it to Foe (historically, Daniel Defoe) for rewriting, at which point the text turns on the question of control over the narrative. Foe constructs alternative accounts of Susans story, including an episode involving the return of a lost daughter which Coetzee takes over from another of Defoes novels, Roxana. The peculiar episode in Slow Man involving Marianna (with two ns) is rather obviously Costellos attempt to do something similar. Its artificiality, tawdriness, and sheer literariness are heavy reminders of its fictionality (not unlike the tawdry story of Roxana herself, the courtesan, whose mystique is revealed by the arrival of her daughter). But Slow Man and Foe are also very different novels, and where one might be willing to accept the metafictional play in Foe where there is a good deal of

7 pastiche and a more obviously allegorical narrative structure, the preponderance of ostensibly realist techniques in Slow Man makes it more difficult to accept. The function of the metafictional elements in Slow Man would seem to be that they turn the novel into an exploration of the relationship between authorship and its creations. Paul Rayment is being written into being by Elizabeth Costello, but he also resists her; in fact, her insistence that he take responsibility for the action, by acting on his desires and by pushing the mortal envelope, as she puts it, would seem to allegorize the kind of negative capability on which a successful narrative would depend. Elizabeth is both predator and parasite, but she insists on Pauls taking charge. Costello is not fully rounded, remaining insubstantial and shadowy, and the reason for this would be Coetzees insistence that writing depends on listening to the counter-voices and relinquishing control. However, if Pauls existence depends on his being written into being by Elizabeth, there is a reciprocal dependency on Elizabeths part. If he has tried to buy himself into the Platonic companionship of the Jokic family as a way of resolving what she calls his unsuitable passion for Marijana, equally she needs Paul to help her cope with her own infirmity and increasingly ugly mortality. The authorial self and the self which is written are subject, it seems, to similar vulnerabilities of need, and the novel wants to undo any mystery there might be around these two roles and present them both in terms that are ordinary and unflattering. By the end, Elizabeths obscure authority is re-contained and she is shown to be subject to impulses much like Pauls, such that in ways so obscure, so labyrinthine that the mind baulks at exploring them, the need to be loved and the storytelling, that is to say the mess of papers on the table, are connected (238).

8 The metafictional dimensions of Coetzees prose have frequently been a way of enacting the conditions of authorship under which he writes. In this respect, the metafiction has been a continuation of the inquiry into the relationship between the subject and history that preoccupies much of the writing it is the same question, taken into the self-reflexivity of art. A fine-tuned understanding of the brutalities of life under colonialism and apartheid, together with a self-consciousness that articulates the prevailing cultural rules and conditions and therefore the codes of its own practice, have made Coetzee the writer he is. In Slow Man, the wider historical resonance of this mode is less in evidence; instead, the colloquies between Paul and Elizabeth seem to reveal an author searching for the substance of his lifes work and wondering whether it lies in the intimate processes of authorship or in the creations which have their existence in the public domain. Whatever the answer, these functions and the personae they entail are stripped of mystique and re-positioned within the rather ordinary world of unexceptional human desires and the moral dilemmas into which they can lead us. Even here, one can discern an attempt to appease the angry gods of history.

II

Let me turn at this point to estrangement. I am alluding here to Nancy Ruttenbergs analysis of Dostoevskys fictionalized autobiography, Notes from the House of the Dead. Ruttenbergs essay was produced as part of a comprehensive revaluation of Victor Shklovskys concept of estrangement or defamiliarization undertaken by the Porter Institute in a recent issue of Poetics Today. Ostranenie, alternatively translated as

9 defamiliarization or estrangement, is given its classic formulation in Shklovskys essay of 1917, Art as Technique. It quickly became recognized as a manifesto of Russian Formalism and subsequently, became established in Western European and American criticism via structuralism and semiotics where it tended to be subsumed into the idea and the critical programme of literariness-as-system. The more recent readings of Shklovsky recontextualize him in terms of what Michael Holquist and Ilya Kliger call a historical poetics; they place Shklovsky alongside his contemporaries in Russian politics and in the cultural movements of Formalism and Futurism, including Bakhtin; they consider the philosophical import of estrangement beginning with Kant; and they consider Shklovskys ideas in relation to those of later writers on the connections between poetics and politics, including and most especially, Hannah Arendt. Ruttenbergs essay participates in this wide-ranging revision, exploring Dostoevskys text as a related but distinct exercise in several kinds of estrangement. The source of Dostoyevskys defamiliarizing narration in House of the Dead is the collapse of his revolutionary assumptions about the peasantry prior to his arrest in 1849 an event involving a bizarre but sadistically faked execution by Czar Nicholas I and subsequent confinement in a Siberian hard-labour camp where he rubbed shoulders day-in and dayout with representatives of the class which until then had largely been the object of his benevolent moral gaze. In the narration of the fictional Gorianchikov, the text stages three levels of estrangement: the shock of encounter with the peasant-convicts who resist his habitual expectations of and beliefs about them; secondly, the narrators hard-won conviction that the abyss dividing the elite from the common classes can only be bridged if the

10 nobleman practices a conscientious self-estrangement; and finally, a level at which the narrator is other to himself, where the object of estrangement is that part of Gorianchikovs consciousness which eludes his own critical regard and remains complicit with non-seeing (721). Underscoring this final, unresolved and confessional aspect of the text is an unintegrated self, what Ruttenberg calls an unconsummated image arising from the unconsummated conversion of the prison experience, one in which despite his best intentions and efforts to do so, Dostoevsky was unable to reform himself (on the model of a religious conversion) as being in possession of an invigorated moral consciousness. In this respect, Ruttenberg reads the prison conversion against accepted biographical accounts, arguing that the yawning gap between Dostoevsky and the peasantry which was opened up during his excruciating imprisonment remains the primary object of inquiry in the text: It is the source of its complex investigation of the psychological, epistemological, political, and spiritual problem of estrangement and the matrix of all unconsummated images (748). I find this analysis suggestive in relation to Coetzee no one who has read Waiting for the Barbarians carefully will fail to be struck by the resonance with that novel of Ruttenbergs notion of the failure of unconsummated images. I need to introduce a few qualifiers, however: there was no prior history in Coetzees case of a revolutionary commitment that went sour, much less of a single watershed experience or passage of his life which ushered in a mature phrase of writing as seems to have been the case with Dostoevsky. I would suggest, though, that we recognize how important it is that Coetzees relationship with South Africa was not one he would have chosen. On the contrary, from the moment he left the country soon after Sharpeville, pursuing, as Youth

11 recounts, a metropolitan dream, he was on the path of emigration until at least the late sixties when his position in the United States became legally untenable. The conditions surrounding his return in 1971 involved his being overwhelmed by circumstance (his failure to achieve permanent residence following an arrest in an anti-war protest); subsequently, South Africa became the unchosen but inescapable milieu in which he would practice his art. We can conclude that there was a Dostoevskian shock of encounter of sorts with South Africa, less with the people, perhaps, than with the whole politico-legal environment, which would leave its mark on Coetzees sense of what the people could and could not achieve. A pattern seems to have been established in 1971 which would remain with him for the next three decades, namely, that he would have to live out (as he puts it in the interview with Dagens Nyeter) his life and work largely in a country with its particular legal, ethical and aesthetic superstructures from which he had sought and failed to escape. This tension is the basis of Coetzeean estrangement, and he has made productive use of it, needless to say. Place in Coetzee, then, is seldom just home, nor is there the process of refamiliarization that one finds in so much postcolonial writing answering metropolitan representations of colonial space. Place for Coetzee is, indeed, a site of Kantian epistemological dualisms, of self-other relationships, of incommensurate orders of knowledge, and of aesthetic destruction (too much truth for art to hold, is the expression [Doubling the Point 99]). All this pushes the subject into a kind of last horizon, which is the space of ironic, reflexive, and metafictional self-scrutiny. Coetzee could not be further from the kind of project which is undertaken by some of the contributors to the recently published A City Imagined, where the specificities of Cape

12 Town are conjured into more comforting representations. The very absence of anything like a Habermasian rational community in Coetzees sense of place, as an intrinsic feature of his postcolony, contributes to the proliferation of what Ruttenberg calls unconsummated images, which in Coetzee are representations which use social incongruity as their point of departure.

III

Let me illustrate some of Coetzees practices of estrangement in the Shklovskian sense, mainly from the early fiction. Famously, there are passages like the following in Dusklands which connect the idea of place with a profound sense of nonbeing: Coetzee glanced neither right nor left as he passed through the defiles of the Khamies mountains. At night the thermometer fell below freezing point. There was snow on the peaks. In the morning the cattle, their joints frozen, had to be lifted to their feet with a pole passed lengthwise under chest and belly. At one of their halts (August 18) the expedition left behind: he ashes of the night fire, combustion complete, a feature of dry climates; faeces dotted in mounds over a broad area, herbivore in the open, carnivore behind rocks; urine stains with minute traces of copper salts; tea leaves; the leg-bones of a springbok; five inches of braided oxhide rope; tobacco ash; and a musket ball. The faeces dried in the course of the day. Rope and bones were eaten by a hyena on August 22. A storm on November 2 scattered all else. The musket ball was not there on August 18, 1933. (126)

This is deixis repeated and overburdened to the point where it loses its deictic function. The effect of such a reversal in the poetics of place is to draw attention to the subjectposition informing the practice the fragile imperial subject; indeed, Coetzee frequently manipulates the poetics of reference in order to foreground a volatile subjectivity. Shklovsky delineates a similar practice in Tolstoy, where the withholding of the referent

13 equally, the pretence that one is seeing the referent for the first time produces the main desired effect. One of Shklovskys examples is drawn from Tolstoys story Shame, where the idea of flogging is treated in this way: to strip people who have broken the law, to hurl them to the floor, to rap on their bottoms with switches, to lash about on the naked buttocks, followed by the dry remark, Just why precisely this stupid, savage means of causing pain and not any other - why not prick the shoulders or any part of the body with needles, squeeze the hands or the feet in a vise [sic], or anything like that? Or in another example, Shklovsky cites the story Kholstomer, where the narrator is a horse, and the horse's point of view makes the content of the story unfamiliar. Here is the horse on the institution of private property:

I understand well what they said about whipping and Christianity. But then I was absolutely in the dark. What's the meaning of his own, his colt? From these phrases I saw that people thought there was some sort of connection between me and the stable. At the time I simply could not understand the connection. Only much later, when they separated me from the other horses, did I begin to understand. But even then I simply could not see what it meant when they called me mans property. The words my horse referred to me, a living horse, and seemed as strange to me as the words my land, my air, my water. But the words made a strong impression on me. I thought about them constantly, and only after the most diverse experiences with people did I understand, finally, what they meant. They meant this: In life people are guided by words, not by deeds. Its not so much that they love the possibility of doing or not doing something as it is the possibility of speaking with words, agreed on among themselves, about various topics. Such are the words my and mine, which they apply to different things, creatures, objects, and even to land, people, and horses. They agree that only one may say mine about this, that, or the other thing. And the one who says mine about the greatest number of things is, according to the game which theyre agreed to among themselves, the one they consider the most happy. (In Victor Shklovsky, Art as Technique.)

Coetzee uses the practice of withholding the obvious referent and/or pretending to encounter it for the first time in the first paragraph of Waiting for the Barbarians:

14

I have never seen anything like it: two little discs of glass suspended in front of his eyes in loops of wire. Is he blind? I could understand it if he wanted to hide blind eyes. But he is not blind. The discs are dark, they look opaque from the outside, but he can see through them. He tells me they are a new invention. They protect ones eyes against the glare of the sun, he says. You would find them useful out here in the desert. They save one from squinting all the time. One has fewer headaches. Look. He touches the corners of his eyes lightly. No wrinkles. He replaces the glasses. It is true. He has the skin of a younger man. At home everyone wears them. (1)

Colonel Jolls personal vanity and dark glasses are, of course, clichs of the security officer familiar with interrogation and torture. Coetzee defamiliarizes the clichs simply by having a narrator who seems to be unfamiliar with them. By the time the magistrate speaks of dark glasses (in the third paragraph) it is as if he had invented the term himself. The object, the glasses, are freed from their conventionalized meanings (habituation is of course Shklovskys term for this) and then recontextualized, such that, in this case, the glasses some to signify the relationship between province and metropolis at home everyone wears them and it is this relationship that will overwhelm the magistrate during the course of the novel and re-introduce the time of Empire as a reign of terror. There would many examples of this practice in Coetzee of withholding common knowledge in order to produce estrangement. In Life and Times of Michael K, the kind of naivety we find in Tolstoys horse is put into the consciousness of K himself, whose simplicity and detachment become the main vehicle for that novels nightmarish representation of late apartheid. Holquist and Kliger, taking the longer philosophical view, show that Shklovskys defamiliarization seeks to overcome the primary Kantian division between ourselves and the meaning or meaningfulness of objects. Coetzees practices of estrangement have the

15 same philosophical pedigree. Both the drama of epistemological separation and the capacity of art to restore newness to objects are explicitly captured in the Postscript to Elizabeth Costello, where writing in the voice of Lady Chandos, wife of Lord Chandos in Hugo van Hoffmannsthals Letter of Lord Chandos to Lord Bacon (1902), Costello says, All is allegory, says my Philip. Each creature is key to all other creatures. A dog sitting in a patch of sun licking himself, says he, is at one moment a dog and at the next a vessel of revelation. And perhaps he speaks the truth, perhaps in the mind of our Creator (our Creator, I say) where we whirl about as if in a millrace we interpenetrate and are interpenetrated by fellow creatures by the thousand. But how I ask you can I live with rats and dogs and beetles crawling through me day and night, drowning and gasping, scratching at me, tugging me, urging me deeper and deeper into revelation how? We are not made for revelation, I want to cry out, not I nor you, my Philip, revelation that sears the eye like staring into the sun. (Elizabeth Costello 229).

Here, Costello is seeking to renounce the intensity of defamiliarization, suggesting that the literary life itself is beginning to pall for her; however, her cries articulate some of the philosophical reaches of Coetzees practice where there is always an undercurrent of anxiety about being denied contact with the world and where the subject has to improvise representational or linguistic solutions to overcome the separation.

IV

Holquist and Kliger dwell on the role of Von Humboldt in approaching Kants phenomenological dualism via the question of language. Von Humboldts great work, they argue, was to overcome Kantian alienation by positing representation through

16 signs as the means by which humans could simultaneously experience and think the world:

He sought to solve the riddle of the I think by transposing the problem into an investigation of the I speak. He began by supposing, together with Kant, that the gap between the categories that ruled perception in the mind, on the one hand, and the existence of the world outside the mind, on the other hand, could not be overcome absolutely. But by negotiating the simultaneity of sign and signified in language, something very like a parallel negotiation mind and world could be accomplished. (emphasis in original; 623)

Coetzees intellectual formation via linguistics at a time when linguistic theory (structuralism, especially, and to a lesser extent generative grammar) seemed to figure centrally in the humanities positioned him in a way that enabled him to enact Von Humboldts solution to Kantian dualism. Every novel foregrounds a particular mode of address in which this parallel negotiation of mind and world is undertaken in a selfconsciously significatory language. Our being drawn, as readers, into the precarious space of the inner speech of the subject, where we are given little else but signs to negotiate a decidedly hostile milieu, accounts in large measure for the sense of compulsion that typically drives us through the Coetzee text. The epistemological drama is in part a drama of survival, where the language of the subject is framed by what Costello calls the mortal envelope. It is this situation, or plight, we might say, that makes Coetzees work resonate so frequently with the fortunes of Crusoe: outside of ordinary social conventions, language is reinvented to ensure the survival and the agency of the subject. But what I wish to emphasize is that this drama is developed not only out of linguistic self-consciousness; it is also as an effect of place, or estranged place. To the Kantian legacy we must add the effects of history: in Coetzees writing, the postcolony is

17 an epistemologically divided space, a space of incommensurability where the subject is forced by circumstance into living out an historical end-game. The question being addressed in the first novel, Dusklands both The Vietnam Project and The Narrative of Jacobus Coetzee - is how does this subject survive, as the heir of the Enlightenment certainly but now on the point of superannuation as the representative of imperialisms last fling: My name is Eugene Dawn. I cannot help that. Here goes. It would be difficult to separate the philosophical from the historical forms of estrangement that develop from this point of entry in the oeuvre. Consider Magda in In the Heart of the Country, offering to the servant, Klein-Anna, what she calls colonial philosophy:

My eye falls idly on objects, odd stones, pretty flowers, strange insects: I pick them up, bear them home, store them away. I am heir to a space of natal earth which my ancestors found good and fenced about. To the spur of desire we have only one response: to capture, to enclose, to hold. But how real is our possession? The flowers turn to dust, the land knows nothing of fences, the stones will be here when I have crumbled away, the very food I devour passes through me. I am not one of the heroes of desire . (114)

In Shklovsky, defamiliarization brought out what he called the stoneness of stones, therefore what Magda offers to Klein-Anna is a kind of Shklovskian lament, in which objects fail to become renewed though she defamiliarizes them by taking them into new contexts, and they fail the test of renewal because her ancestors and what they represent have corrupted the impulse for renewal at its core. In other words, there is no renewal of vision outside of history and historical relationships. The colonial provenance of desire ensures that our Kantian alienation from the meaningfulness of objects is always passed through the Hegelian dualism of master and slave. This point is driven home poignantly by the rhetorical context of Magdas speech, which is addressed to Klein-Anna as an

18 appeal for understanding but in the clear knowledge that such comfort will not be forthcoming. Famously, to Klein-Anna die Mies is die Mies. Age of Iron begins with the following two sentences: There is an alley down the side of the garage, you may remember it, you and your friends would sometimes play there. Now it is a dead place, waste, without use, where windblown leaves pile up and rot (1). In the next few paragraphs, we learn that Vercueil has taken up residence in this alley on the day that Mrs Curren learns about her terminal condition. The alley is a featureless place which in the past was rendered meaningful by the play of the daughter and her friends; now it is a space of waste, a dead place, where windblown leaves pile up and rot. This, too, is a renewal of sorts, a renewal of representation in which meaningfulness returns in an unexpected if unwelcome way; the interruption which causes the estrangement in this instance is the presence of death the news of Mrs Currens cancer, the appearance of Vercueil, and the absence of the daughter. It is against this dark background of morbidity that Cape Town in the mid-1980s will be reassessed; a defamiliarization of place so complete that a re-examination of social relationships including the possibility of love between Mrs Curren and her daughter, and between Mrs Curren and the uncompromising young men who will inherit the new social order can be explored de novo.

Works Cited

Svetlana Boym, Poetics and Politics of Estrangement: Victor Shklovsky and Hannah Arendt, Poetics Today 26, 4 (Winter 2005): 581-611.

19 J.M. Coetzee. Age of Iron. London: Secker and Warburg, 1990. Dusklands. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1974. Elizabeth Costello: Eight Lessons. London: Secker and Warburg, 2003. In the Heart of the Country. London: Secker and Warburg, 1977. Waiting for the Barbarians. London: Secker and Warburg, 1980. Michael Holquist and Ilya Kliger, Minding the Gap: Towards a Historical Poetics of Estrangement, Poetics Today 26, 4 (Winter 2005): 613-636. Nancy Ruttenberg, Dostoevskys Estrangement, Poetics Today 26, 4 (Winter 2005): 719-751.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Myth at Heart of BrandDocument12 pagesMyth at Heart of Branddekonstrukcija100% (1)

- Albert Memmi - Decolonization and The DecolonizedDocument7 pagesAlbert Memmi - Decolonization and The DecolonizeddekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Celtic Settlement in North-Western Thrace During The Late Fourth and Third Centuries BC Some Archaeological and Historical Notes - Nikola TeodossievDocument15 pagesCeltic Settlement in North-Western Thrace During The Late Fourth and Third Centuries BC Some Archaeological and Historical Notes - Nikola TeodossievEvsNo ratings yet

- Celtic Settlement in North-Western Thrace During The Late Fourth and Third Centuries BC Some Archaeological and Historical Notes - Nikola TeodossievDocument15 pagesCeltic Settlement in North-Western Thrace During The Late Fourth and Third Centuries BC Some Archaeological and Historical Notes - Nikola TeodossievEvsNo ratings yet

- Maspok Komunisti I NacionalizamDocument21 pagesMaspok Komunisti I NacionalizamdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Narayan - Native AnthropologistDocument17 pagesNarayan - Native AnthropologistdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Dystopian Cinderellas - I Follow Him Into The DarkDocument321 pagesDystopian Cinderellas - I Follow Him Into The DarkdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Hellenophilia Vs History of ScienceDocument11 pagesHellenophilia Vs History of Sciencedekonstrukcija100% (1)

- Chatman - Story and DiscourseDocument285 pagesChatman - Story and Discoursevruiz_206811100% (8)

- A.dundes, Binary Opposition in Myth - Propp-Levi StrosDocument13 pagesA.dundes, Binary Opposition in Myth - Propp-Levi StrosdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- J.G.cawelti, Concept of Formula in Study of Popular LiteraturDocument10 pagesJ.G.cawelti, Concept of Formula in Study of Popular LiteraturdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Snow Falling on Cedars as a Historical Crime NovelDocument17 pagesSnow Falling on Cedars as a Historical Crime NoveldekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of Murder: Mystery, Detective, and Crime FictionDocument21 pagesAnatomy of Murder: Mystery, Detective, and Crime Fictiondekonstrukcija100% (2)

- Isaac1978 - Protohuman HominidsDocument16 pagesIsaac1978 - Protohuman HominidsdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- C.P.kottak, Rituals at McDonald's, V.1.No.2.1978Document7 pagesC.P.kottak, Rituals at McDonald's, V.1.No.2.1978dekonstrukcija100% (1)

- A.dundes, Binary Opposition in Myth - Propp-Levi StrosDocument13 pagesA.dundes, Binary Opposition in Myth - Propp-Levi StrosdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Bertrand Russell - Why I Am Not A ChristianDocument15 pagesBertrand Russell - Why I Am Not A ChristianDan GlinskiNo ratings yet

- Bowlin Stromberg - Representation Reality Study of CultureDocument13 pagesBowlin Stromberg - Representation Reality Study of CulturedekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- 39 Qualitative Research Issues and MethodsDocument28 pages39 Qualitative Research Issues and MethodsdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Creating Culture Through Choosing HeritageDocument15 pagesCreating Culture Through Choosing HeritagedekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Museums and IdentitiesDocument16 pagesMuseums and IdentitiesdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Displaying Nationality As Traditional Culture in The Belgrade Ethnographic MuseumDocument14 pagesDisplaying Nationality As Traditional Culture in The Belgrade Ethnographic MuseumdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Quarantelli - The Studies of Desaster MoviesDocument30 pagesQuarantelli - The Studies of Desaster Moviesdekonstrukcija0% (1)

- Ethnographic Content Analysis 1987Document13 pagesEthnographic Content Analysis 1987Bigolo1960No ratings yet

- Belk Possessions Sense of PastDocument9 pagesBelk Possessions Sense of PastdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- Slobodan Naumovic - Romanticists or Double InsidersDocument21 pagesSlobodan Naumovic - Romanticists or Double InsidersdekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- White PrivilegeDocument21 pagesWhite Privilegedekonstrukcija33% (3)

- Influence of Oxygen in Copper - 2010Document1 pageInfluence of Oxygen in Copper - 2010brunoNo ratings yet

- Giraffe Juice GamesDocument32 pagesGiraffe Juice Gamesgwyn022100% (3)

- Guimaras State CollegeDocument5 pagesGuimaras State CollegeBabarianCocBermejoNo ratings yet

- Sea Cities British English Teacher Ver2Document6 pagesSea Cities British English Teacher Ver2Kati T.No ratings yet

- Tithi PRAVESHADocument38 pagesTithi PRAVESHAdbbircs100% (1)

- SEW Motor Brake BMGDocument52 pagesSEW Motor Brake BMGPruthvi ModiNo ratings yet

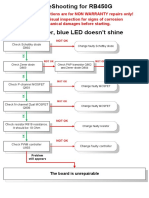

- RB450G Trouble ShootingDocument9 pagesRB450G Trouble Shootingjocimar1000No ratings yet

- Alaris 8210 and 8220 SpO2 Module Service ManualDocument63 pagesAlaris 8210 and 8220 SpO2 Module Service ManualNaveen Kumar TiwaryNo ratings yet

- G String v5 User ManualDocument53 pagesG String v5 User ManualFarid MawardiNo ratings yet

- Kuliah 1 - Konservasi GeologiDocument5 pagesKuliah 1 - Konservasi GeologiFerdianNo ratings yet

- Cygnus 4plus Operating ManualDocument141 pagesCygnus 4plus Operating Manualdzul effendiNo ratings yet

- Engine Controls (Powertrain Management) - ALLDATA RepairDocument5 pagesEngine Controls (Powertrain Management) - ALLDATA RepairXavier AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Language Culture and ThoughtDocument24 pagesLanguage Culture and ThoughtLý Hiển NhiênNo ratings yet

- Brake System PDFDocument9 pagesBrake System PDFdiego diaz100% (1)

- Final Term Quiz 2 On Cost of Production Report - Average CostingDocument4 pagesFinal Term Quiz 2 On Cost of Production Report - Average CostingYhenuel Josh LucasNo ratings yet

- Laser Module 5Document25 pagesLaser Module 5Luis Enrique B GNo ratings yet

- Objective QuestionsDocument19 pagesObjective QuestionsDeepak SharmaNo ratings yet

- Column and Thin Layer ChromatographyDocument5 pagesColumn and Thin Layer Chromatographymarilujane80% (5)

- The Critical Need For Software Engineering EducationDocument5 pagesThe Critical Need For Software Engineering EducationGaurang TandonNo ratings yet

- 123 The Roots of International Law and The Teachings of Francisco de Vitoria As A FounDocument23 pages123 The Roots of International Law and The Teachings of Francisco de Vitoria As A FounAki LacanlalayNo ratings yet

- Rules For Assigning Activity Points: Apj Abdul Kalam Technological UniversityDocument6 pagesRules For Assigning Activity Points: Apj Abdul Kalam Technological UniversityAnonymous KyLhn6No ratings yet

- Schwarzschild Metric and Black Hole HorizonsDocument39 pagesSchwarzschild Metric and Black Hole Horizonsসায়ন চক্রবর্তীNo ratings yet

- Demand Performa For Annual DemandDocument10 pagesDemand Performa For Annual DemandpushpNo ratings yet

- 2VAA001695 en S Control NTCS04 Controller Station Termination UnitDocument43 pages2VAA001695 en S Control NTCS04 Controller Station Termination UnitanbarasanNo ratings yet

- Ancon Channel & Bolt FixingsDocument20 pagesAncon Channel & Bolt FixingsatiattiNo ratings yet

- Gentle Classical Nature Sample - Units1 and 2Document129 pagesGentle Classical Nature Sample - Units1 and 2Carita HemsleyNo ratings yet

- Fort St. John - Tender Awards - RCMP Building ConstructionDocument35 pagesFort St. John - Tender Awards - RCMP Building ConstructionAlaskaHighwayNewsNo ratings yet

- Sci9 Q4 Mod8.2Document24 pagesSci9 Q4 Mod8.2John Christian RamosNo ratings yet

- Vega Plus 69Document3 pagesVega Plus 69yashNo ratings yet

- The UFO Book Encyclopedia of The Extraterrestrial (PDFDrive)Document756 pagesThe UFO Book Encyclopedia of The Extraterrestrial (PDFDrive)James Lee Fallin100% (2)