Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nation Branding, Loyalty Towards The Country.

Uploaded by

rotxeeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nation Branding, Loyalty Towards The Country.

Uploaded by

rotxeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Nation Branding Loyalty towards the country, the state and the service brands

Received (in revised form): 19th April, 2002

AUDHESH K. PASWAN

is Assistant Professor in the Department of Marketing and Logistics, COBA, UNT. He has a PhD (Marketing) from the University of Mississippi, an MBA from IIM, Ahmedabad, India, and a BTech in Aeronautics from IIT, Madras, India. His research has appeared in forums such as Journal of Business Research, Journal of Retaining, Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, Journal of Marketing Education, Journal of Product and Brand Management, Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, Journal of International Consumer Marketing and numerous national and international conferences. His research interests include areas such as franchising/channels, international/cross-cultural, relational norms brand management, knowledge management, technology and organisation, and social issues such as consumerism. His current teaching portfolio includes classes such as Marketing Research, Marketing Engineering (MBA) and Multivariate Statistics (PhD).

SHAILESH KULKARNI

is Assistant Professor of Management Science in the COBA at UNT. His areas of interest lie in stochastic models of supply chain management, quality control applications, service operations modelling and the marketing-manufacturing interface. He has published papers in journals such as the International Journal of Production Economics and Integrated Manufacturing Systems, among others.

GOPALA GANESH

ia a professor in the Department of Marketing and Logistics, College of Business Administration, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas. He teaches Marketing Research, Marketing Management and Applied Multivariate Methods at the undergraduate and graduate levels. He has also created a unique class for undergraduate marketing majors, called Marketing Tools, that seeks to strengthen the analytical and presentation skills of these students using mini-cases, Excel speadsheets and PowerPoint presentations. His current research interests include proling afuent consumers, online shopping by households and business, proling international students in the US and household decision making. Dr Ganesh has published papers in journals such as International Marketing Review, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Journal of Services Marketing, Journal of Marketing Education, Marketing Education Review and Journal of Global Marketing.

Abstract

This study empirically investigates the notion of brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the service provider, and investigates the relationship between the strength of loyalty towards the three country, state and service brands. In addition, contingency variables such as national origin, social class and educational level are examined. The results indicate that brand loyalty towards the country is strongest, followed by that towards the state and service provider. As regards the contingency variables, both social class and education were found to have signicant impact on the brand loyalty towards the service provider. The results for national origin indicated that loyalty towards the country, the state and the service brands does differ by country. In summary, the authors conclude that brand loyalty towards the country and the state tends to be more stable than loyalty towards the service brand.

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003 233

Audhesh K. Paswan Department of Marketing, College of Business Administration, University of North Texas, PO Box 311396, Denton, TX 76203-1396, USA Tel: 1 940 565 3121 Fax: 1 940 565 3837 E-mail: paswana@unt.edu

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

INTRODUCTION

The country of origin image as an important determinant of product or service brand image has been extensively investigated in international marketing literature.13 There seems to be a general consensus that country image and brand image are inextricably linked.46 The causal nature of this relationship is not unequivocal, however. Several countries have followed the path of rst enhancing the image of their brands in the host country and then using that to later bolster the country image. This was especially true in the post-war era for emerging economies, for example, several Asian and Latin American countries. Then there are others who have tried to position their brands as an extension of their country image, for example, Germany, Switzerland, etc. Some obvious examples may be found in the travel and tourism service industry, where promotion of the country as a brand is not uncommon. Little attention, however, has been given to the systematic investigation of nations as brands, although there are some exceptions to this.710 This study empirically investigates the notion of brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the service brands, and the interactions between them. This is crucial now, when services dominate national and international trade. In the case of the USA, over 60 per cent of its GNP and 80 per cent of its jobs are tied to the service sector.11,12 This scenario is likely to be very similar for most industrialised nations and even for developing or emerging economies.13,14 Moreover, services are distinctly different from products in terms of intangibility, heterogeneity

234

or variability, perishability of output, and inseparability of production and consumption.15 They tend to be low in search quality (no xed, temporally stable characteristics such as colour, style, shape, hardness, smell etc), and relatively high on experience and credence qualities. In other words, consumers can assess the service quality mainly during and after the consumption. Sometimes, even that is not possible, and consumers have to assess service quality based on beliefs that, in turn, may be based on factors not necessarily associated with the core service exchanged.16,17 Interestingly, these descriptors sound as though they pertain to the country or even the state as brands. The investigation reported here is particularly noteworthy since it is carried out in the context of the exchange of higher education services between US higher educational institutions and international students. This is a unique exchange that typically takes a long time to complete, consists of core and augmented services, and is delivered in several stages, with milestones along the way. Studies conducted in an educational services context have acknowledged education to be one of the most intangible exchange items.1821 Additionally, education has a different meaning for people of different cultures. It ranges from a meal ticket, to a way of elevating ones social status, to meeting self-actualisation needs. Moreover, the international student body is slowly becoming a market to reckon with, and its decision-making process involves the university and the country of location in a very complex and inextricable manner.2224 These arguments, plus the fact that

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

the international student market is a force to reckon with, make higher education an interesting setting for investigating the notion of the country, the state and the service provider as brands. To start with, the ndings of this study should enrich an understanding of the interaction between the country-brand versus brands within the nation. At a micro level, the results of this study have direct implications for the international marketing of higher education as well as any other services, especially ones whose delivery follows a similar process. Finally, service rms could gain valuable insights into the strategic and tactical aspects of marketing across cultures. This manuscript begins with a description of the higher education market to contextualise the investigation. This is followed by a discussion of brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the service brands, contingency variables, and the development of hypotheses. The methodology is then presented, followed by the results, and nally a discussion of the limitations and implications both research and managerial of this study.

US higher education institutions are losing ground to competition from other countries.2729 Based on the earlier successes of their US counterparts, universities in Canada, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Singapore and some European countries have started marketing their higher education systems to international students. Clearly, the international student markets cannot be ignored. In order to tap into this market, universities have undertaken aggressive marketing campaigns. These include bringing students to the home campus, setting up campuses in the host markets (for example, Indian Business School and INSEADs Singapore campus), and even using commercial means such as franchising, for example, the entry by Wigan and Leigh College (UK) into the Indian market.30 Added to this competitive pressure, the global higher education market has had its own ups and downs, trends and cycles based on economic, social, legal, regulatory and political happenings.3133

BRAND LOYALTY COUNTRY, STATE AND SERVICE BRANDS

The concept of the brand, and its related issues such as brand equity, brand recall, brand insistence and brand evaluation have attracted extensive research scrutiny.3436 A related body of knowledge deals with the country of origin image research stream.3742 The notion of country as brand has hardly received attention, however, except for pioneering works by authors such as Anholt43 and OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy.44 A general consensus in the country of origin literature is that country of

235

THE HIGHER EDUCATION SERVICE AND THE INTERNATIONAL MARKET

Foreign student enrolment in US universities has been growing steadily over the years.25 While foreign students account for only 3 per cent of all US higher education enrolments, their presence in graduate education is disproportionately high (11 per cent).26 They have an even greater presence in some academic elds such as engineering, business and computer science. There are, however, indications that

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

origin is often used as a cue for evaluating new products. In general, favourable country perceptions result in favourable inferences about product attributes and subsequent favourable evaluations.4547 Recent studies, however, question the weight given to country of origin in the product evaluation process.48,49 These investigations suggest that culture-specic factors tend to determine the weight assigned to the country-of-origin factor. For example, even if people from certain parts of China feel positively about Japanese products, they are less likely to buy the Japanese product because of past negative history. A similar conclusion may be drawn from studies dealing with brand extension if a country is treated as a brand.5053 While OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy have taken a cautious approach to the idea of treating the country as a brand, Anholt is more enthusiastic in suggesting the notion of provenance.54,55 Anholt further suggests that developed countries tend to have very strong provenance, and do use it in more or less the same way as rms use the notion of brand extension, for example, German automobiles, Swiss watches, Scotch whisky, etc.56 In fact, this phenomenon manifests itself very strongly in the travel and tourism industry. For example, countries like the Bahamas, Brazil, the Caribbean Islands (including Jamaica), etc, have successfully created a country brand identity and market their products and services (travel and tourism, rum and even entire lifestyles) as an extension. Other examples include products and services such as Egyptian cotton, Chinese silk, Indian hospitality, etc. Another example of country branding can be found in the context of

236

higher education services especially aimed at international students. The USA probably has the strongest country brand.57 Other countries such as Canada, Australia and the UK are not doing too badly either. Students from all over the world engage in decisions about their eld of study, the university, and the country almost simultaneously. Often, their decisions about eld of study and college/university are strongly linked to, if not inuenced by, their decision about the country. In general, the countries are more easily recognisable to international students than, say, the state where the university of interest may be located, or even the university of choice. As a result, information that could shape brand loyalty towards the country, ie the USA, is likely to be more easily accessible to students than that for the state and the service provider, ie the university. Some exceptions are universities such as Harvard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Oxford and Cambridge. Providers of these higher education brands have created a brand identity that somehow transcends the country brand image, although some spillover is inevitable. As a group, most international students tend to gravitate towards relatively well-known and reputed universities. As a result, these students are likely to be more satised with their experiences with the education they receive; the core of the exchange. Their interaction with the university at large is not, however, likely to be favourable all the time. There are likely to be instances where they encounter interactions that run contrary to their previous expectations. As a result, their brand loyalty towards the university is

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

likely to be more diffused, and not very high in comparison to brand loyalty towards the country. Similar thoughts have been alluded to in the services literature, for example, the amount of contact or interaction, and the continuum of tangible-intangible and abstractness.5861 In addition, OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy62 suggest that the brand image of a nation tends to be nebulous and complex. On the other hand, the brand image of a specic service provider is likely to be narrower in scope and more task-fullment oriented. Loyalty towards the state brand is likely to be very similar to that exhibited towards the service brand. Support for this line of thinking comes from the choice procedure typically adopted by students. For example, after deciding on the country for higher education, students select a university and/or the state. In fact, it is quite possible that the choice of state becomes more or less a default, given a decision about the university. The choice of university itself is dependent upon the eld of study, nancial aid, reputation of the university, and the students performance in required tests, for example, Graduate Record Examinations (GRE), the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) and the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL). One could also argue that a negative experience with the university brand may have a spillover effect on the state brand, since policies and activities at most state universities are linked to the states socio-economic conditions and policies. Support for this line of thinking comes from the literature on brand image and schematic memory (or

knowledge structure), which suggests that brand image is a schematic memory of a brand.6365 Relying on this literature as well as current thinking on brand extension, one could argue that a more complex knowledge structure for a country is likely to be associated with a stronger brand image and brand loyalty.66 In addition, one could speculate that the complex knowledge structure associated with the country brand is likely to shield it from extreme swings in post-experience loyalty. In comparison, because of a narrower and more task-specic orientation, the university is likely to acquire a more diffused brand image. Different people have different expectations from the university, and therefore their postexperience assessments also vary. An analogous example could be the knowledge structure associated with God, the religious institution and the priest. Irrespective of the name used, the imagery associated with the word God tends to be fairly consistent across different religious groups benevolent, protector, creator, saviour, redeemer, judge, etc. When it comes to the knowledge structure associated with the (local as well as somewhat distant) institution of religion and the priest, however, one encounters very diverse feelings and imageries. Thus the authors speculate that loyalty towards the country brand is likely to be higher in terms of magnitude, and lower in terms of dispersion, than the state and university brands. The loyalty towards the state and the university brands is, however, likely to be equal in terms of both magnitude and dispersion. H1a: Loyalty towards the country brand will be higher than loyalty towards the state brand.

237

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

H1b: Loyalty towards the country brand will be higher than loyalty towards the university brand. H1c: Loyalty towards the state brand will be equal to loyalty towards the university brand. H2a: Loyalty towards the country brand will be less diffused than loyalty towards the state brand. H2b: Loyalty towards the country brand will be less diffused than loyalty towards the university brand. H2c: Loyalty towards the state brand will be equally diffused as loyalty towards the university brand. As indicated in the literature, this notion of brand loyalty is not absolute and universal. Among the contingent factors identied, cultural and national background, social class, education and experience with the brand seem to emerge as more important ones.6769 The possible relationships are now explored between these contingent factors and the notion of brand loyalty towards the country brand, state brand and the university-of-choice brand.

National origin

National origin is a frequently encountered variable in the country of origin literature, as well as in global and international marketing literature.7073 It seems to be a commonly used independent or contingent variable and, for the most part, is presumed to capture the feelings associated with the country of origin in the international marketing of brands. National origin as a variable has also been recommended as a surrogate for cultural differences, even though scholars have

238

dened culture in multiple ways.74 80 Engel et al.81 saw it as the values, ideas, attitudes, and other meaningful symbols that help individuals communicate, interpret, and evaluate as members of society. According to Hofstede,82 culture is the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from another (p. 21). Huntington83,84 suggested that religious traditions are the foundation of culture, and divide the world into eight cultural zones western Christianity, Orthodox world, Islamic world, Confucian, Japanese, Hindu, African and Latin American. In a recent study, Inglehart and Baker85 found that economic developments change the culture of a society and shift it away from the absolute norms. The broad cultural heritage of a society, however, creates values that endure despite modernisation. Based on these arguments, the authors will use national origin as one of the contingent variables. Extant literature suggests that brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the university brands can be placed in some continuum along the levels of abstractness abstract versus concrete, high versus low levels of interaction, consistent versus nebulous, etc.86,87 Given the focus here higher education most students (international or not) come to a university for more or less the same reasons: to get higher education. The experiences of these students are, however, likely to be very different, and because of the proximal and concrete nature of the interaction, their experiences at the university are likely to inuence their loyalty towards the university. In addition, students from the same country

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

tend to share their experiences, and thus induce some homogeneity in their brand imagery about the university. Students may not, however, share their experiences with others from different countries, unless they are very close friends. Thus one could speculate that students from the same country are likely to have a more consistent brand image and hence a more consistent loyalty (measured as propensity to recommend) than students from different countries. In other words, the loyalty towards university brands is likely to differ across a range of students from different countries. Similar arguments could be used to speculate that brand loyalty towards the country and the state are also likely to be different for students from different countries. Apart from the rationale presented earlier, cross-national or cultural differences could also determine assessments of experiences and consequently the loyalty towards the country, the state and the university brands. H3a: Loyalty towards the country brand will differ across national origin. H3b: Loyalty towards the state brand will differ across national origin. H3c: Loyalty towards the university brand will differ across national origin.

Social class

In addition to the national origin, social class has been identied in the cross-culture literature as a key determinant of cultural distance.8891 Social class is often used as a surrogate for ability to buy, world awareness,

afuence, social status and power, etc. In the context of this study, the authors contend that social class is likely to have a strong inuence on the respondents comfort level with other cultures. People from the upper social class, in most societies, have access to information, travel and other similar methods of exposure to other cultures. Consequently, they are more comfortable than other classes in interacting with people from other cultures, and while they may or may not emulate the moral values of those cultures, these elites are likely to be more comfortable with different values. This means that people from the upper social strata are likely to be more aware of the minutiae of distant countries even without rsthand experience, in comparison to people from lower social classes. The knowledge could be gained through the medium of interaction (English versus vernacular) until high school, type of schools attended in the native country, international journals, magazines, friends or relatives living in different countries, lms and TV programmes. All these are often not within easy grasp of people from the lower strata. There is likely to be a more divergent brand loyalty towards the university across different social strata. Given the argument that state choice is attached to the university choice, this scenario should also hold true for brand loyalty towards the state. The countrylevel brand loyalty, however, is likely to be similar across different social strata due to the fact that people from all walks of life may identify with a single enduring value system and, despite being exposed to divergent country-level information, they may

239

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

still draw a similar conclusion.9294 The notion of patriotism, ethnic pride and maybe even ethnocentrism enter the picture, resulting in a more homogenous image of target countries as a brand, across different social strata. This leads to the next set of hypotheses: H4a: Social class will have no inuence on loyalty towards the country brand. H4b: Social class will positively inuence loyalty towards the state brand. H4c: Social class will positively inuence loyalty towards the university brand.

Education and experience

The last contingent variable, the level of education, has been posited to be one of the most inuential demographic variables.95,96 It can also be seen as a measure of experience with the brand at the service-provider, ie the university, level. Literature suggests that education hopefully enhances ones awareness about the world in general. It also typically results in a more favourable opinion towards foreign products, and a reduction in ethnocentrism.9799 In addition, education also captures the notions of maturity, awareness and the passage of time and hence more experience with the service under investigation. As regards the university, international students, whether they seek undergraduate or graduate education, are likely to be driven by similar motivations. In addition, their experiences with the university are likely to be uniform across academic levels. In other words, a university with

240

a mediocre educational programme would be perceived as such by everyone. Therefore, the authors propose that the academic level of a respondent is not likely to have any inuence on brand loyalty towards the university. The level of education is, however, likely to be related to loyalty towards the country and state brands. For most international students, their tenure of stay in the country and the state is likely to coincide with their stay at their university, and there should be a high level of congruence between the three. As international students stay on longer in the country they are likely to experience more of that countrys society, both the good and the bad. It may erode some of their preconceived notions and euphoria, and subsequently lead to lowering of brand loyalty towards the state and the country as brands. Literature on acculturation suggests similar stages of experience among expatriates and people who travel.100 These arguments form the basis for the last set of hypotheses relating to respondents educational levels and brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the university: H5a: Level of education (seen as more intimate experience with the environment) will be negatively associated with loyalty towards the country brand. H5b: Level of education (seen as more intimate experience with the environment) will be negatively associated with loyalty towards the state brand. H5c: Level of education will not be associated with loyalty towards the university brand.

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

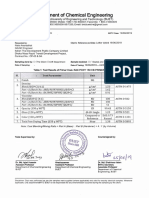

Table 1 Propensity to recommend (loyalty to) the country, the state and the university: Pair-wise comparison results means and variance Paired Samples Statistics Propensity to Recommend Mean Pair 1 Pair 2 Study in the USA Study in Texas Study in the USA Study at the current university Study in Texas Study at the current university 2.401 3.286 2.401 3.327 3.288 3.327

N 1261 1261 1259 1259 1259 1259

SD 1.574 1.957 1.574 2.065 1.958 2.065

t-stats 16.689 15.896

sig (2-tail) F-stats sig (1-tail) Corr. 1.04E-22 1.04E-22 1.546 1.721 0.00 0.00 0.448 0.380

Pair 3

0.8386

0.401829

1.113

0.03

0.666

Bartlett's test: M = 331.11; C = 1; M/C = 330.99; P-value = 0.00. SD: Standard deviation. Scale range: 1 = definite yes and 9 = definite no.

The following section details the methodology used for testing these hypotheses.

METHODOLOGY

The respondents for this study were international students currently enroled at four Texas universities with comprehensive programmes ranging from undergraduate to doctorate, and enrolments ranging from 25,000 to nearly 50,000. The sampling frame consists of around 8,000 international students (about 25 per cent of all international students on Texas campuses). The mailing list was generated with the help of the international student ofce at each university. The survey questionnaire was mailed out to a stratied disproportionate random sample of 4,000 international students (ie 1 out of every 2), 1,000 from each university. A notication letter plus the single mailing resulted in 1,400 responses (a response rate of 35 per cent). The brand loyalty towards the country (USA), the state (Texas) and the university was measured by

students willingness to advocate these as a place for higher education. The authors used a nine-point scale anchored by denitely yes (1) and denitely no (9). Extant studies have suggested word of mouth and willingness to be an advocate as acceptable measures.101104 In addition, students were also asked about their home country social class (upper class, upper middle class, middle class and lower middle class), academic classication (undergraduate (freshman/sophomore/undergraduate junior and senior), masters and PhD), and their nationality.

ANALYSES AND RESULTS

The data were rst tested for nonresponse error by matching the prole of the respondents with the known prole characteristics of the population of nearly 4,000 international students. There were no signicant differences. The scale items measuring brand loyalty were rst subjected to a test for internal consistency using Chronbachs Alpha. The substantive

241

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

Table 2

ANOVA results: Propensity to recommend versus national origin USA Mean 2.411 2.798 2.786 1.905 2.543 3.089 1.904 2.442 2.733 2.140 1.846 2.435 Texas Mean 3.032 3.640 3.589 2.809 4.114 3.842 2.692 3.346 3.261 3.124 3.128 3.305 Current university N Mean SD 185 3.443 89 3.798 55 3.982 94 2.915 70 3.800 101 3.832 52 2.404 52 3.173 45 3.111 113 3.239 39 3.077 895 3.393 Stats 1.955 2.007 1.748 1.987 2.096 2.069 2.041 2.121 1.584 2.122 2.107 2.034 Sig

Country/Recommendation 1.00 People's Republic of China 2.00 Taiwan 3.00 Hong Kong 4.00 India 5.00 Japan 6.00 Korea 7.00 Mexico 8.00 MalaysiaIndonesia 9.00 Thailand 15.00 Western Europe 16.00 Eastern Europe Total

N 185 89 56 95 70 101 52 52 45 114 39 898 Stats

SD 1.576 1.707 1.681 1.238 1.621 1.850 1.418 1.526 1.436 1.275 1.329 1.577

N 185 89 56 94 70 101 52 52 46 113 39 897 Stats

SD 1.635 1.848 1.766 1.902 2.313 1.810 2.119 2.177 1.625 1.847 2.250 1.923 Sig

Sig

Homogeneity of variance (Levene's test) ANOVA (F-test)

2.45 5.556

0.01 0.00

2.5 4.232

0.01 0.00

0.939 3.743

0.496 0.00

Homogenous subsets: bold high loyalty; italics low loyalty; others average loyalty. SD: Standard deviation. Scale range: 1 = definite yes and 9 = definite no.

relationships captured by the proposed hypotheses were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Table 1 presents the ndings of pair-wise comparison between the mean and variance estimates of brand loyalties towards the country (USA), the state (Texas) and the service provider (students current university). The Bartletts test, F-test and t-test provide support for H1a, H1b, H1c, H2a and H2b, but not for H2c. In other words, loyalty towards the country brand is highest, followed by the state and the university brands. Loyalty towards the state and the university brands is equal. In addition, the variance in loyalty towards the university brand is highest, followed by the state brand, and nally by the country brand. Table 2 presents the ANOVA results for the national origin of the student

242

as a contingent variable. It suggests that the brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the university differ across national origin. The homogeneity of variance test (Levenes test), however, indicates that although variance in brand loyalty towards the country and the state are not homogenous, the brand loyalty towards the university as a brand is homogenous. This provides clear support for H3a and H3b, but only partial support for H3c. Using only the frequency counts of respondents who indicated high brand loyalty (below 5), the authors then tested for independence (chi square) between brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the university, and country of origin. The results (Table 3) indicate that brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the university are independent of country of origin.

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

Table 3 Test of independence: Brand loyalty versus national origin Hong Kong 49 43 34 126 MalaysiaWestern Indonesia Thailand Europe 45 40 39 124 39 36 34 109 108 88 86 282 Eastern Europe Total 35 29 29 93 791 684 640 2,115

Observed Country State University Total

China 162 155 134 451

Taiwan 77 62 58 197

India 93 80 73 246

Japan 58 42 44 144

Korea 78 67 65 210

Mexico 47 42 44 133

1 Brand loyalty towards Chi sq calc. 3.622 Chi sq test 31.41 2 Brand loyalty towards Chi sq calc. 2.083 Chi sq test 18.31 3 Brand loyalty towards Chi sq calc. 1.558 Chi sq test 18.31 4 Brand loyalty towards Chi sq calc. 1.787 Chi sq test 18.31

the country-state-university versus national origin:

the country-state versus national origin:

the country-university versus national origin:

the state-university versus national origin

Table 4

ANOVA results: Propensity to recommend versus social class Homogeneity of variance Levene stats Sig 1.690 0.167

Propensity to Recommend Study in the USA Upper class Upper middle class Middle class Lower middle class Total Upper class Upper middle class Middle class Lower middle class Total Upper class Upper middle class Middle class Lower middle class Total

N 98 500 515 118 1,231 97 499 516 118 1,230 97 498 515 118 1,228

Descriptive Mean SD 2.500 2.292 2.468 2.390 2.391 3.113 3.132 3.434 3.542 3.297 2.938 3.245 3.423 3.729 3.342 1.812 1.520 1.572 1.558 1.571 2.184 1.870 1.943 2.190 1.964 2.135 1.992 2.095 2.155 2.068

ANOVA results F-stats Sig 1.232 0.297

Study in Texas

2.920

0.033

2.668

0.046

Study at the current university

3.256

0.021

2.077

0.101

SD: Standard deviation. Bartletts test for loyalty towards the country, state and service brands resulted in significant p-value. Scale range: 1 = definite yes and 9 = definite no.

The means of the brand loyalty scores across country of origin were then examined to see if these are homogenous subsets. For brand loyalty towards the country, eastern Europe, Mexico and India seem to form one cluster with very high brand loyalty,

with Korea at the other end of the scale, with very low brand loyalty. Countries like those in western Europe, China, Malaysia-Indonesia, Japan, Thailand, Hong Kong and Taiwan seem to form the middle group. As regards brand loyalty

243

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

Table 5 ANOVA results: Propensity to recommend versus educational level Homogeneity of variance Levene stats Sig

Propensity to Recommend Study in the USA

N Undergraduate freshman, sophomore 120 Undergraduate junior, senior 284 Master's 432 PhD 385 Total 1,221 Undergraduate freshman, sophomore 120 Undergraduate junior, senior 284 Master's 432 PhD 385 Total 1221 Undergraduate freshman, sophomore 120 Undergraduate junior, senior 283 Master's 432 PhD 384 Total 1,219

Descriptive Mean SD

ANOVA results F -stats Sig

2.217 2.546 2.299 2.530 2.421 3.325 3.419 3.051 3.439 3.286 3.333 3.463 3.241 3.354 3.337

1.502 1.776 1.485 1.529 1.576 1.954 2.152 1.849 1.878 1.948 2.243 2.124 2.067 1.968 2.067

2.759

0.041

2.601

0.051

Study in Texas

3.364

0.018

3.932

0.008

Study at the current university

0.671

0.570

1.343

0.259

SD: Standard deviation. Bartletts test for loyalty towards the country, state and service brands resulted in significant p-value. Scale range: 1 = definite yes and 9 = definite no.

towards the state, Mexico seems to have the highest brand loyalty, Japan the lowest, with India, China, West and East Europe, Thailand, Malaysia Indonesia, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Korea forming the middle group. When it came to brand loyalty towards the university as a brand, students from Mexico again scored very high, students from Hong Kong very low, with students from other countries in the middle. Table 4 presents the ANOVA results for social class as a contingent variable. The results indicate that the mean score for brand loyalty towards the country does not vary across social strata, whereas brand loyalty towards the state and the university does vary

244

across social class, with higher social classes exhibiting higher loyalty (this supports H4a, H4b and H4c). Further tests were performed for distribution of brand loyalty across social class by using Bartletts test for unequal variance. The results indicate that the distribution of brand loyalty towards the country, the state and the university differs across social class. The variance in brand loyalty towards the country increases with an increase in social class. Brand loyalty towards the state and the university seems to be more diverse within the upper social class and lower middle social class than within the upper-middle class and the middle class. Table 5 presents the ANOVA results

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

for the educational levels as the contingent variable. The results provide clear support for H5a and H5b. Brand loyalty scores do vary across educational level. For the country and state brands, the undergraduates (freshman and sophomore) and masters students exhibit higher levels of brand loyalty than the undergraduates (senior and junior) and PhD students. The brand loyalty towards the university does not change across academic levels (H5c also supported). Further analysis of variance (Bartletts test) suggests that variance in loyalty does differ across academic classication for all the country, state and the university as brands.

DISCUSSION

This study presented the results of empirical investigation of brand loyalty towards the country, state and service provider (in this case, the university), and the interrelationships between these and contingency variables such as national origin, social class and educational level. The support for hypotheses 1 and 2 suggests that brand loyalty towards the country brand is more stable than the brand loyalty towards the state and the service provider (ie university). Brand loyalty is also the highest in the context of the focal country USA. Clearly, the brand concept of the nation is much more complex than the brand concept of the service brand. It can be argued that, because of this, the nation brand is likely to be more deeply rooted than the state or the service brand. As a result, the stability of the country brand should not come as a surprise. Support for this line of thinking comes from assertions made by both Anholt

and OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy.105107 Extant literature on schematic memory (or knowledge structure) also corroborates the ndings of this study, and the rationale about the strength of the country brand versus the service brand.108110 Possible explanations for the differences in brand loyalty across national origin (H3) may lie in the language, cultural and maybe even historical differences. The fact that students from Europe, Mexico and India exhibit higher levels of loyalty towards the country brand could be attributed to their language and/or ethnic proximity towards substantial numbers of mainstream US students and the population at large. Even geographical proximity, in the case of Mexican students, could be a possible explanation for high levels of brand loyalty. Another possible explanation could be the similarities and differences between US society and other societies investigated here.111 It must, however, be kept in mind that this paper is investigating students who have ventured beyond their normal limits and are generally more cosmopolitan than the peers they have left behind. It may be difcult to explain the behaviour and attitudes by any one single factor. Most country of origin studies have focused on the national origin and found it to be a signicant inuencing factor. This brings one to the hypotheses (H4) regarding social class. The results clearly indicate that people from upper social strata exhibit higher levels of brand loyalty towards the state and the university. They are more comfortable in the alien environment, which results in higher levels of loyalty towards service brands. The social class

245

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

does not, however, seem to have any inuence on the country brand. This indicates that while consumers from different social classes may have similar views towards a particular country, they may be very divergent in their views about products and brands from that country. Typically, people from upper strata have had access to so-called foreign cultures and have even taken pride in using that to differentiate themselves from the masses. This comfort with social interaction does not, however, trickle down to comfort with the country as a brand, which is more enduring and stable across social classes. A similar idea seems to be captured by the brand community concept proposed by Muniz and OGuinn.112 Finally, the result for educational level suggests that brand loyalty levels get weaker with experience, and this weakening process seems to be signicant for country and state brands and not for service brands. In other words, for both country and state brands, students tend to start out with high levels of brand loyalty, which diminishes with experience (see the loyalty scores for freshman/sophomore versus junior/senior undergraduate students, and for masters versus PhD students). A possible explanation may come from the notion of acculturation.113 Brand loyalty towards a specic service provider brand does not, however, seem to vary signicantly with experience. Could it be that a more-focused brand image remains relatively untainted with experience? Having decided on a service provider for a specic task, the post-purchase experience either fulls a consumers expectation or it does not. It is conceivable that a simpler brand image

246

(or schematic memory of a brand) is less sensitive to negative experiences. On the other hand, a complex brand image consisting of a complex schematic structure and network, while initially resulting in a stronger brand image, is also open to dilution of these schematic linkages as a result of unexpected post-purchase experience.

LIMITATIONS

A key limitation of this study is the sampling frame, which consists exclusively of international students attending four large universities in Texas. Given the focal service context, however, the authors believe that this is not too inappropriate. An obvious research implication would be to investigate this phenomenon in a different market and in different product contexts. For example, future research attention should be directed towards testing whether country brand loyalty remains stable across different target nations developed versus developing, US versus European, or Asian countries, etc. Research should also be conducted in a context that involves product brand as against service brand.

IMPLICATIONS

The ndings of this study have important managerial implications for international marketing of 114,115 services. The authors conclude that brand loyalty towards the country (USA) seems to be more stable, and higher, than brand loyalty towards the state (Texas) and the service provider (ie university). Marketers need to be cognisant of this phenomenon since it can be easily exploited for

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

a more favourable product/brand positioning.116 A counter-argument could be that countries can enlist the private sector to enhance country brand equity.117 More specically, the ndings of this study have interesting managerial implications for services where completion takes a long time and is composed of several stages and subtasks, for example, higher education, turnkey projects, civic amenities contracts, once-in-a-lifetime services such as extended and risky medical treatments, and social services such as family planning or projects to bring about changes in social behaviour such as drug abuse. Because services tend to be highly intangible, it is not unreasonable to speculate that consumers are likely to use other cues for assessing their quality. It is quite possible that the country brand is just one such cue. Another managerial implication is in the area of segmentation and targeting of services. It is a fact that in every society there will be people who are more worldly-wise and will welcome things being different, somewhat vindicating the notion of global marketing.118 It is possible to market standardised services across the globe. The key is to nd people who are more attuned to, and are acculturated into, the service providers sociocultural milieu. The other option is to understand the socio-cultural mores and values of the target market and align ones offering. The relationship between the country brand and service or the product brand could be a very good tool for segmentation and market size estimation. At an operational level, the ndings of this study have interesting implications for brands and branding.119,120

This is especially crucial when product or service brands are marketed in a host country.121,122 It is not uncommon for the brand position of the product or service to interact with the brand image of the home country.123,124 How will a German rm position its range of cosmetics given its current image of robust technology-oriented products such as its automobiles? Given its strong brand equity, can the USA expect all its products to have the same strong image in every country? The answer, most would agree, is no. In India, US cars are not perceived to be of as high a quality as German cars or, for that matter, Japanese cars, even if all these brands of cars are made in India. It is not unreasonable to speculate that the process of branding a service or a product must take into account the brand equity of the home country. To complicate matters even more, the brand image of a country is dynamic and is determined by factors often not related to the brand image of the specic service or product. For example, the current events triggered by the September 11th incident are bound to have an impact on the brand image of the USA. It would be interesting to investigate what impact it will have on brands marketed by US companies. Based on the ndings here, there is one saving grace loyalty towards a specic service brand seems to be less sensitive to experiential disappointments and related shifts in loyalty towards the country brand. It seems that it is possible for a service brand to survive on its own merit, probably because of its narrow and task-oriented positioning. So long as a service brand

247

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

fulls its promise, often relatively narrowly dened, the brand image can remain relatively unscathed by shifts in the country brand image. In contrast, country brands are more complex and hence are more susceptible to inuences from a larger domain of factors. By the same token, the complexity of the knowledge structure associated with the country brand may actually protect it from extreme uctuations. Research on brand association provides some corroboration for these arguments.125 Finally, the ndings of this study have implications for immigrationrelated public policies dealing with, and impacting, the future of US higher education. A related area of public policy would be labour policy, especially pertaining to the highly educated international labour market. Recent ups and downs in the high technology labour markets due to the upheavals in technology-based industries more than highlight the point discussed here. At an institutional level, the ndings have implications for methods and procedures for marketing of higher educational institutions, especially to the international education market. There is also the notion of ethics: should only students from certain countries and social strata be allowed, with standardised offerings to t their needs? This may make life a little easier for service providers including universities. The other option is more difcult invite everyone from everywhere to study in the USA, and maybe some of them will add to the so-called melting pot. A related public policy implication lies in the domain of governments seeking the help of the private sector, or requiring the private sector to enhance

248

country brand equity. The authors hope that questions such as these attract the attention of their academic colleagues, managers as well as policy makers. Clearly, the area of investigation encompassing country brand versus service or product brand is an uncharted one and holds unlimited surprises in terms of knowledge to be discovered.

References

(1) Al-Sulaiti, K. I. and Baker, M. J. (1998) Country of origin effects: A literature review, Marketing Intelligence and Planning, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 150199. (2) Li, Z. G. and Murray, W. L. (2000) Global sourcing, multiple country-of-origin facets, and consumer reactions, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 47, Issue 2, pp. 121144. (3) Zhang, Y. (1997) Country-of-origin effect: The moderating function of individual difference in information processing, International Marketing Review, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 266287. (4) dAstous, A. and Ahmed, S. A. (1999) The importance of country images in the formation of consumer product perceptions, International Marketing Review, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 108125. (5) Batra, R., Venkatram, R., Alden, D. L., Jan-Benedict, S. E. M. Steenkamp, E. M. and Ramachandran, S. (2001) Effects of brand local and nonlocal origin on consumer attitudes in developing countries, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 8396. (6) Kim, C. K. and Chung, J. Y. (2001) Brand popularity, country image and market share: An empirical study, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 361387. (7) Anholt, S. (2000) Another One Bites the Grass Making Sense of International Advertising, John Wiley and Sons Inc., New York. (8) Anholt, S. (2000) The nation as brand, Across the Board, Nov/Dec, pp. 2227. (9) Anholt, S. (1998) Brazil should follow lead of brand USA., Advertising Age International, September, Vol. 12. (10) OShaughnessy, J. and OShaughnessy, N. J. (2000) Treating the nation as a brand: Some neglected issues, Journal of Macromarketing, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 5664. (11) Brady, M. K. and Robertson, C. J. (2001)

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

(12)

(13)

(14)

(15) (16) (17)

(18)

(19)

(20) (21)

(22)

(23)

(24)

(25)

Searching for consensus on the antecedent role of service quality and satisfaction: An exploratory cross-national study, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 51, No. 1, pp. 5360. Shugan, S. M. (1994) Explanations for the growth of services, in Rust, R. T. and Oliver, R. L. (Eds) Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 7294. Kapur, D. and Ramamurti, R. (2001) Indias emerging competitive advantage in services, Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 2033. Riddle, D. I. (1986) Service-led Growth. The Role of the Service Sector in World Development, Praeger, New York. Lovelock, C. H. (1996) Services Marketing, 3rd edn, Prentice Hall, New Jersey. Lovelock, ref. 15 above. Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L. and Parasuraman, A. (1993) The nature and determination of customer expectation of service, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 112. Boulding, W., Kalra, A., Staelin, R. and Zeithaml, V. A. (1993) A dynamic process model of service quality: From exceptions to behavioral intentions, Journal of Marketing Research, February, pp. 727. Boulding, W., Kalra, A., Staelin, R. and Zeithaml, V. A. (1992) Conceptualizing and testing a dynamic process model of service quality, Marketing Science Institute, technical working paper, Report No. 92121, August. Lovelock, ref. 15 above. Zeithaml, V. A. (1981) How consumer evaluation processes differ between goods and services, The Marketing of Services, Proceedings of the 1981 National Services Conference, Donnelly, J. (Ed) AMA, Chicago, pp. 186190. Desruisseaux, P. (1999) Foreign students continue to ock to the US, Chronicle of Higher Education, Vol. 16, No. 6, pp. A5659. Desruisseaux, P. (1998) Intense competition for foreign students sparks concern about US standing, Chronicle of Higher Education, Vol. 45, No. 7, pp. A5557. Tomovick, C., Jones, S. I., Al-Khatib, J. and Baradwaj, B. G. (1996) An assessment of the service quality provided to foreign students at US business schools, Journal of Education for Business, Vol. 71, No. 3, pp. 130135. Bourke, A. (2000) A model of the determinants of international trade in higher

(26)

(27) (28) (29)

(30)

(31) (32) (33) (34)

(35)

(36)

(37) (38) (39)

(40) (41)

(42)

(43) (44) (45)

(46)

education, Service Industries Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1. Open Doors (19992000) Institute of International Education, New York, http://www.opendoors.web.org. Desruisseaux, ref. 22 above. Desruisseaux, ref. 23 above. Desruisseaux, P. (1996) US is less hospitable nowadays, foreign students and scholars nd, Chronicle of Higher Education, Vol. 43, No. 14, p. A45. USDOC (2000) India Franchising Scenario, International Trade Administration, IMI20000313. Desruisseaux, ref. 22 above. Desruisseaux, ref. 23 above. Tomovick et al., ref. 24 above. Muniz, A. M. and OGuinn, T. C. (2001) Brand community, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 27, March, pp. 412432. Schultz, D. E. (2000) Understanding and measuring brand equity, Marketing Management, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 89. Yoo, B. and Donthu, N. (2001) Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 123. Al-Sulaiti and Baker, ref. 1 above. dAstous and Ahmed, ref. 4 above. Kim, C. K. (1995) Brand popularity and country image in global competition: Managerial implications, Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 4, No. 5, pp. 2133. Kim and Chung, ref. 6 above. Lee, D. and Ganesh, G. (1999) Effects of partitioned country image in the context of brand image and familiarity, International Marketing Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 1839. Voss, K. E. and Patriya, T. (1999) A consumer perspective on foreign market entry: Building grands through brand alliances, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 3958. Anholt, ref. 8 above. OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy, ref. 10 above. Gurhan-Canli, Z. and Maheswaran, D. (2000) Cultural variations in country of origin effects, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 309318. Hong, S. and Wyer, R. S. (1990) Determinants of product evaluation: Effects of the time interval between knowledge of a products country of origin and information about its specic attributes,

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

249

PASWAN, KULKARNI AND GANESH

(47)

(48)

(49)

(50)

(51)

(52) (53) (54) (55) (56) (57) (58)

(59) (60)

(61) (62) (63)

(64)

(65)

Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 17, December, pp. 277288. Lecrec, F., Schmitt, B. and Dube, L. (1994) Foreign branding and its effects on product perception and attitudes, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 31, May, pp. 263270. Bozell-Gallup (1996) The Second Annual Bozell-Gallup Worldwide Quality poll, Bozell Worldwide, New York. Klein, J. G., Ettenson, R. and Morris, M. D. (1998) The animosity of model of foreign product purchase: An empirical test in the Peoples Republic of China, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 62, January, pp. 89100. Bhat, S. and Reddy, S. K. (2001) The impact of parent brand attribute associations and affect on brand extension evaluation, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 53, No. 3, pp. 111122. Sheinin, D. A. (2000) The effects of experience with brand extension on parent brand knowledge, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 4750. Anholt, ref. 8 above. OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy, ref. 10 above. Anholt, ref. 8 above. OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy, ref. 10 above. Anholt, ref. 8 above. Anholt, ref. 7 above. Albers-Miller, N. D. and Stafford, M. A. (1999) International services advertising: An examination of variation in appeal use for experiential and utilitarian services, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 13, No. 4/5, pp. 390406. Brady and Robertson, ref. 11 above. Parasuraman, A., Berry, L. A. and Zeithaml, V. A. (1991) Renement and reassessment of the SER VQUAL scale, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 67, No. 4, pp. 420450. Lovelock, ref. 15 above. OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy, ref. 10 above. Smith, R. A., Houston, M. J. and Childers, T. L. (1985) The effects of schematic memory on imaginal information processing, Psychology and Marketing, Spring, pp. 1329. Park, C. W., Jaworski, B. J. and MacInnis, D. J. (1986) Strategic brand concept-image management, Journal of Marketing, October, pp. 135145. Barich, A. and Kotler, P. (1991) A framework for marketing image management, Sloan Management Review, Winter, pp. 94104.

(66) Sheinin, ref. 51 above. (67) Gurhan-Canli and Maheswaran, ref. 45 above. (68) Al-Sulaiti and Baker, ref. 1 above. (69) Sheinin, ref. 51 above. (70) Al-Sulaiti and Baker, ref. 1 above. (71) Hofstede, G. (1991) Cultures and Organizations Software of the Minds, McGraw-Hill Book Company, London. (72) Hofstede, G. (1980) Cultures Consequences: International Differences in Work Related Values, Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA. (73) Samiee, S. (1999) The internationalization of services: Trends, obstacles, and issues, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 13, No. 4/5, pp. 319328. (74) Hofstede, ref. 71 above. (75) Hofstede, ref. 72 above. (76) Huntington, S. P. (1996) The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, Simon and Schuster, New York. (77) Huntington, S. P. (1993) The clash of civilizations? Foreign Affairs, Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 2249. (78) Inglehart, R. and Baker, W. E. (2000) Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values, American Sociological Review, Vol. 65, February, pp. 1951. (79) Samiee, ref. 73 above. (80) Trompenaars, F. (1994) Riding the Waves of Culture, Irwin, New York. (81) Engel, J. F., Blackwell, R. D. and Miniard, P. W. (1995) Consumer Behavior, 8th edn, p. 144, The Dryden Press, Orlando, FL. (82) Hofstede, ref. 72 above. (83) Huntington, ref. 76 above. (84) Huntington, ref. 77 above. (85) Inglehart and Baker, ref. 78 above. (86) Albers-Miller and Stafford, ref. 58 above. (87) OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy, ref. 10 above. (88) Al-Sulaiti and Baker, ref. 1 above. (89) Hofstede, ref. 71 above. (90) Inglehart and Baker, ref. 78 above. (91) Levitt, T. (1983) The globalization of markets, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 61, No. 3, pp. 92102. (92) Hofstede, ref. 71 above. (93) Hofstede, ref. 72 above. (94) Inglehart and Baker, ref. 78 above. (95) Al-Sulaiti and Baker, ref. 1 above. (96) Festervand, T., Lumpkin, J. and Lundstrom, W. (1985) Consumers perception of imports: An update and extension, Akron Business and Economic Review, Vol. 16, Spring, pp. 3136. (97) Good, L. K. and Huddleston, P. (1995)

250

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

LOYALTY TOWARDS THE COUNTRY, THE STATE AND THE SERVICE BRANDS

(98)

(99)

(100) (101) (102) (103) (104) (105) (106) (107) (108) (109) (110) (111) (112) (113) (114)

Ethnocentrism of Polish and Russian consumers: Are feelings and intentions related? International Marketing Review, Vol. 12, No. 5, pp. 3548. Sharma, S., Shimp, T. and Shin, J. (1995) Consumer ethnocentrism: A test of antecedents and moderators, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 2637. Bailey, W. and Pineres, S. (1997) Country of origin attitudes in Mexico: The Malinchismo effect, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 2541. Hofstede, ref. 72 above. Boulding et al., ref. 18 above. Boulding et al., ref. 19 above. Bourke, ref. 25 above. Tomovick et al., ref. 24 above. Anholt, ref. 7 above. Anholt, ref. 8 above. OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy, ref. 10 above. Smith et al. ref., 63 above. Park et al. ref., 64 above. Barich and Kotler, ref. 65 above. Hofstede, ref. 71 above. Muniz and OGuinn, ref. 34 above. Hofstede, ref. 71 above. Douglas, S. P., Craig, C. S. and Nijssen, E. J. (1999) Executive insights: Integrating

(115) (116) (117)

(118) (119)

(120) (121)

(122)

(123) (124) (125)

branding strategy across markets: Building international brand architecture, Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 97114. Samiee, ref. 73 above. Anholt, ref. 7 above. Anonymous (2000) Private sector urged to promote countrys image, Business Times, 21st June. Levitt, ref. 91 above. dHauteserre, A. (2001) Destination branding in a hostile environment, Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 39, February, pp. 300307. Park et al. ref., 64 above. Agarwal, J. and Wagner, A. K. (1999) Country of origin: A competitive advantage, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 16, pp. 255267. Ha ubl, G. and Elrod, T. (1999) The impact of congruity between brand name and country of production on consumers product quality judgments, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 16, pp. 199215. dAstous and Ahmed, ref. 4 above. Kim, ref. 39 above. Low, G. S. and Lamb, C. W. (2000) The measurement and dimensionality of brand associations, Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 9, No. 6, pp. 350368.

HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1350-231X BRAND MANAGEMENT VOL. 10, NO. 3, 233251 FEBRUARY 2003

251

Copyright of Journal of Brand Management is the property of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Public No More: A New Path to Excellence for America’s Public UniversitiesFrom EverandPublic No More: A New Path to Excellence for America’s Public UniversitiesNo ratings yet

- International Marketing Dissertation ExamplesDocument6 pagesInternational Marketing Dissertation ExamplesWebsiteThatWillWriteAPaperForYouSavannah100% (1)

- Values and Perceptions of Graduate SchoolsDocument21 pagesValues and Perceptions of Graduate SchoolsKevin TameNo ratings yet

- Branding Higher Education The Case of MalaysianDocument19 pagesBranding Higher Education The Case of MalaysianKinying ChengNo ratings yet

- How To Connect With Your Best Student Prospects: Saying The Right Things, To The Right Students, in The Right MediaDocument21 pagesHow To Connect With Your Best Student Prospects: Saying The Right Things, To The Right Students, in The Right MediapedropauloNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Methods in International Sales Research: Cross-Cultural ConsiderationsDocument16 pagesQualitative Methods in International Sales Research: Cross-Cultural ConsiderationsNurrohmah 'Hhabibah' OzoraNo ratings yet

- Thesis Report On Marketing MixDocument6 pagesThesis Report On Marketing MixPayForAPaperYonkers100% (2)

- Dissertation Topics On SmesDocument5 pagesDissertation Topics On SmesPayingSomeoneToWriteAPaperUK100% (1)

- Educational Marketing Strategies On The Market of Higher Education ServicesDocument11 pagesEducational Marketing Strategies On The Market of Higher Education ServicesGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Marketing Thesis PDFDocument7 pagesMarketing Thesis PDFjuliegonzalezpaterson100% (1)

- Creating Brand Value in Higher EducationDocument7 pagesCreating Brand Value in Higher EducationcrisseveroNo ratings yet

- Interpret Market Trends and Developments TASK 2Document11 pagesInterpret Market Trends and Developments TASK 2Raí Silveira100% (1)

- Research Paper On Advertising and ConsumerismDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Advertising and Consumerismgz9p83dd100% (1)

- Cross Cultural Marketing ThesisDocument6 pagesCross Cultural Marketing Thesisallisonschadedesmoines100% (2)

- U of California - DavisDocument6 pagesU of California - DavisMichaelNo ratings yet

- Zainudin Awang Utm Dr. K PDFDocument16 pagesZainudin Awang Utm Dr. K PDFNazaniah Badrun0% (1)

- Marketing Literature Review ExampleDocument4 pagesMarketing Literature Review Exampleafmzodjhpxembt100% (1)

- Factors Influencing The Choice of Higher EducationDocument5 pagesFactors Influencing The Choice of Higher EducationMruthunjayaNo ratings yet

- 2017 Strategic Brand MGMT For Higher Education Institutions With Graduate Degree Programs Marketing MixDocument22 pages2017 Strategic Brand MGMT For Higher Education Institutions With Graduate Degree Programs Marketing MixViolet SkcNo ratings yet

- Sales Performance ThesisDocument7 pagesSales Performance ThesisWhereToBuyResumePaperLosAngeles100% (2)

- Understanding Generation Y and Their Use of Social Media A Review and Research AgendaDocument42 pagesUnderstanding Generation Y and Their Use of Social Media A Review and Research AgendaKiahJepunNo ratings yet

- Lsbu Coursework Cover SheetDocument8 pagesLsbu Coursework Cover Sheetafjwduenevzdaa100% (2)

- Literature Review On Country of Origin EffectDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Country of Origin Effectaflspfdov100% (1)

- Word of Mouth Master ThesisDocument5 pagesWord of Mouth Master Thesisfbzgmpm3100% (2)

- Marketing Communications Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesMarketing Communications Literature Reviewafmzmajcevielt100% (1)

- Dissertation Marketing InternationalDocument8 pagesDissertation Marketing InternationalCustomPaperWritingServicesSingapore100% (1)

- Thesis Marketing PDFDocument5 pagesThesis Marketing PDFiapesmiig100% (3)

- Impact of Advertising On Consumer Buying Behaviour Research PaperDocument6 pagesImpact of Advertising On Consumer Buying Behaviour Research PaperafedtkjdzNo ratings yet

- Marketing Master Thesis TopicsDocument5 pagesMarketing Master Thesis Topicsnicolewilliamslittlerock100% (2)

- Thesis Country of OriginDocument6 pagesThesis Country of Originlesliedanielstallahassee100% (1)

- Cross Cultural Competence Master ThesisDocument5 pagesCross Cultural Competence Master Thesiscarolinalewiswashington100% (2)

- Erasmus Marketing Thesis AwardDocument6 pagesErasmus Marketing Thesis Awarddwt5trfn100% (2)

- An Empirical and Qualitative Study of The Strategic Planning Process of A Higher Education InstitutionDocument12 pagesAn Empirical and Qualitative Study of The Strategic Planning Process of A Higher Education Institutionpolaris2184No ratings yet

- The National Basketball Association: A Case in International Marketing Kyle Richard Moon & John J. Lawrence (Faculty Supervisor) University of IdahoDocument11 pagesThe National Basketball Association: A Case in International Marketing Kyle Richard Moon & John J. Lawrence (Faculty Supervisor) University of IdahoMuzahid KhanNo ratings yet

- Social Media Ties Strategy in International Branding An Application of Resource-Based TheoryDocument26 pagesSocial Media Ties Strategy in International Branding An Application of Resource-Based Theoryxueliyan777No ratings yet

- Master Dissertation TopicsDocument7 pagesMaster Dissertation TopicsHelpWithPaperErie100% (1)

- Cardiff University Dissertation ProposalDocument6 pagesCardiff University Dissertation ProposalCustomHandwritingPaperLittleRock100% (1)

- Public Relations Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesPublic Relations Literature Reviewafmzweybsyajeq100% (1)

- Logos, Ethos, Pathos and The Marketing of Higher EducationDocument20 pagesLogos, Ethos, Pathos and The Marketing of Higher Educationcr19020No ratings yet

- Dissertation Structure University of BedfordshireDocument6 pagesDissertation Structure University of BedfordshireWhereToBuyCollegePapersUK100% (1)

- Master Thesis On Marketing ManagementDocument5 pagesMaster Thesis On Marketing Managementafjrooeyv100% (2)

- The Impact of Marketing Strategies and Satisfaction On Student Loyalty: A Structural Equation Model ApproachDocument11 pagesThe Impact of Marketing Strategies and Satisfaction On Student Loyalty: A Structural Equation Model ApproachRosh ElleNo ratings yet

- As of September 2010 Revision: A. Application For Admission To The UST GraduateDocument2 pagesAs of September 2010 Revision: A. Application For Admission To The UST GraduateTristan Bill AbadNo ratings yet

- Advertising ThesisDocument6 pagesAdvertising Thesisgj84st7d100% (2)

- 07 Ijmres 10032020Document12 pages07 Ijmres 10032020International Journal of Management Research and Emerging SciencesNo ratings yet

- Social media marketing and consumer behavior studyDocument6 pagesSocial media marketing and consumer behavior studynastaeenbaig1No ratings yet

- Literature Review On Marketing Strategy PDFDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Marketing Strategy PDFfuhukuheseg2100% (1)

- PhD Handbook Lindner College BusinessDocument22 pagesPhD Handbook Lindner College BusinessNasimNo ratings yet

- Executive Summaries: S U F M KDocument5 pagesExecutive Summaries: S U F M KTeodora VintilaNo ratings yet

- Marketing Sustinability ProposalDocument9 pagesMarketing Sustinability ProposaljasmirsinghNo ratings yet

- Jma 20121 ADocument15 pagesJma 20121 AIsmael SotoNo ratings yet

- Thesis DHLDocument4 pagesThesis DHLSomeoneWriteMyPaperWashington100% (4)

- Branding CollegeDocument2 pagesBranding CollegePuneet BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Consumer-Brand Relationship: Foundation and State-Of-The-ArtDocument21 pagesConsumer-Brand Relationship: Foundation and State-Of-The-ArtMarium AslamNo ratings yet

- Tourism Destination ThesisDocument6 pagesTourism Destination ThesisCollegePaperWritingServicesMilwaukee100% (2)

- Literature Review of Consumer Buying BehaviourDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Consumer Buying Behaviourafmznqfsclmgbe100% (1)

- Arm Doc 1Document12 pagesArm Doc 1Sapna RohitNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Branding TopicDocument4 pagesDissertation Branding TopicBuyWritingPaperElgin100% (1)

- Dissertation On Marketing MixDocument7 pagesDissertation On Marketing MixPaySomeoneToWritePaperCanada100% (1)

- Review of Literature On Consumer Brand PreferenceDocument5 pagesReview of Literature On Consumer Brand PreferenceafduaciufNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship Project-NishantDocument80 pagesSummer Internship Project-Nishantnishant singhNo ratings yet

- Bethany Getz ResumeDocument2 pagesBethany Getz Resumeapi-256325830No ratings yet

- Estwani ISO CodesDocument9 pagesEstwani ISO Codesनिपुण कुमारNo ratings yet

- My16-Td My16-AtDocument6 pagesMy16-Td My16-AtRodrigo ChavesNo ratings yet

- Homo Sapiens ActivityDocument8 pagesHomo Sapiens ActivityJhon Leamarch BaliguatNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 - Mock Test - English - Feb - 2023Document12 pagesGrade 10 - Mock Test - English - Feb - 2023rohanNo ratings yet

- Java MCQ QuestionsDocument11 pagesJava MCQ QuestionsPineappleNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 CMADocument10 pagesLesson 5 CMAAssma SabriNo ratings yet

- Trimble Oem Gnss Bro Usl 0422Document3 pagesTrimble Oem Gnss Bro Usl 0422rafaelNo ratings yet

- Castel - From Dangerousness To RiskDocument10 pagesCastel - From Dangerousness To Riskregmatar100% (2)

- Hotel Design Planning and DevelopmentDocument30 pagesHotel Design Planning and DevelopmentTio Yogatma Yudha14% (7)

- Product Catalog 2016Document84 pagesProduct Catalog 2016Sauro GordiniNo ratings yet

- Rakpoxy 150 HB PrimerDocument1 pageRakpoxy 150 HB Primernate anantathatNo ratings yet

- The Graduation Commencement Speech You Will Never HearDocument4 pagesThe Graduation Commencement Speech You Will Never HearBernie Lutchman Jr.No ratings yet

- HU675FE ManualDocument44 pagesHU675FE ManualMar VeroNo ratings yet

- 7 Tactical Advantages of Explainer VideosDocument23 pages7 Tactical Advantages of Explainer Videos4ktazekahveNo ratings yet

- PowerhouseDocument10 pagesPowerhouseRanjan DhungelNo ratings yet

- Aircraft ChecksDocument10 pagesAircraft ChecksAshirbad RathaNo ratings yet

- Galvanometer: Project Prepared By:-Name - Pragati Singh Class - Xii A AcknowledgementDocument11 pagesGalvanometer: Project Prepared By:-Name - Pragati Singh Class - Xii A AcknowledgementANURAG SINGHNo ratings yet

- Khaton Prayer BookDocument47 pagesKhaton Prayer BookKarma TsheringNo ratings yet

- 9AKK101130D1664 OISxx Evolution PresentationDocument16 pages9AKK101130D1664 OISxx Evolution PresentationfxvNo ratings yet

- DNT Audit Cash CountDocument2 pagesDNT Audit Cash CountAnonymous Pu7TnbCFC0No ratings yet

- Practical LPM-122Document31 pagesPractical LPM-122anon_251667476No ratings yet

- K Series Parts List - 091228Document25 pagesK Series Parts List - 091228AstraluxNo ratings yet

- Strain Gauge Sensor PDFDocument12 pagesStrain Gauge Sensor PDFMario Eduardo Santos MartinsNo ratings yet

- A.2.3. Passive Transport Systems MCQsDocument3 pagesA.2.3. Passive Transport Systems MCQsPalanisamy SelvamaniNo ratings yet

- Impact of Recruitment & Selection on Employee RetentionDocument39 pagesImpact of Recruitment & Selection on Employee RetentiongizawNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis of Algorithms Prof. Madhavan Mukund Chennai Mathematical Institute Week - 01 Module - 01 Lecture - 01Document8 pagesDesign and Analysis of Algorithms Prof. Madhavan Mukund Chennai Mathematical Institute Week - 01 Module - 01 Lecture - 01SwatiNo ratings yet

- ChE 135 Peer Evaluation PagulongDocument3 pagesChE 135 Peer Evaluation PagulongJoshua Emmanuel PagulongNo ratings yet

- What Is Rack Chock SystemDocument7 pagesWhat Is Rack Chock SystemSarah Perez100% (1)

- Defensive Cyber Mastery: Expert Strategies for Unbeatable Personal and Business SecurityFrom EverandDefensive Cyber Mastery: Expert Strategies for Unbeatable Personal and Business SecurityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Python for Beginners: The 1 Day Crash Course For Python Programming In The Real WorldFrom EverandPython for Beginners: The 1 Day Crash Course For Python Programming In The Real WorldNo ratings yet

- Ultimate Guide to LinkedIn for Business: Access more than 500 million people in 10 minutesFrom EverandUltimate Guide to LinkedIn for Business: Access more than 500 million people in 10 minutesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- So You Want to Start a Podcast: Finding Your Voice, Telling Your Story, and Building a Community that Will ListenFrom EverandSo You Want to Start a Podcast: Finding Your Voice, Telling Your Story, and Building a Community that Will ListenRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (35)

- The Digital Marketing Handbook: A Step-By-Step Guide to Creating Websites That SellFrom EverandThe Digital Marketing Handbook: A Step-By-Step Guide to Creating Websites That SellRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- How to Be Fine: What We Learned by Living by the Rules of 50 Self-Help BooksFrom EverandHow to Be Fine: What We Learned by Living by the Rules of 50 Self-Help BooksRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (48)

- How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention EconomyFrom EverandHow to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention EconomyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (421)

- Content Rules: How to Create Killer Blogs, Podcasts, Videos, Ebooks, Webinars (and More) That Engage Customers and Ignite Your BusinessFrom EverandContent Rules: How to Create Killer Blogs, Podcasts, Videos, Ebooks, Webinars (and More) That Engage Customers and Ignite Your BusinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- The Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for PowerFrom EverandThe Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- Nine Algorithms That Changed the Future: The Ingenious Ideas That Drive Today's ComputersFrom EverandNine Algorithms That Changed the Future: The Ingenious Ideas That Drive Today's ComputersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Ultimate Guide to YouTube for BusinessFrom EverandUltimate Guide to YouTube for BusinessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- SEO: The Ultimate Guide to Optimize Your Website. Learn Effective Techniques to Reach the First Page and Finally Improve Your Organic Traffic.From EverandSEO: The Ultimate Guide to Optimize Your Website. Learn Effective Techniques to Reach the First Page and Finally Improve Your Organic Traffic.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Facing Cyber Threats Head On: Protecting Yourself and Your BusinessFrom EverandFacing Cyber Threats Head On: Protecting Yourself and Your BusinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (27)

- The $1,000,000 Web Designer Guide: A Practical Guide for Wealth and Freedom as an Online FreelancerFrom EverandThe $1,000,000 Web Designer Guide: A Practical Guide for Wealth and Freedom as an Online FreelancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- Monitored: Business and Surveillance in a Time of Big DataFrom EverandMonitored: Business and Surveillance in a Time of Big DataRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)