Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Supply Chain Revolution

Uploaded by

Kea Plamiano AlvarezOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Supply Chain Revolution

Uploaded by

Kea Plamiano AlvarezCopyright:

Available Formats

The Supply Chain Revolution

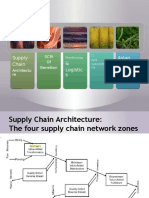

What managers are experiencing today we choose to describe as the supply chain revolution and a related logistical renaissance. These two massive shifts in expectation and practice concerning best-practice performance of business operations are highly interrelated. However, supply chain and logistics are significantly different aspects of contemporary management. Supply chain management consists of multiple firms collaborating to leverage strategic positioning and to improve operating efficiency. For each firm involved, the supply chain relationship reflects a strategic choice. A supply chain strategy is a channel and business organizational arrangement based on acknowledged dependency and collaboration. Supply chain operations require managerial processes that span traditional functional areas within individual firms and link suppliers, trading partners, and customers across business boundaries. Within a firms supply chain management, logistics is the work required to move and geographically position inventory. As such, logistics is a subset of and occurs within the broader framework of a supply chain. Logistics is the process that creates value by timing and positioning inventory. Logistics is the combination of a firms order management, inventory, transportation, warehousing, materials handling, and packaging as integrated throughout a facility network. Integrated logistics serves to link and synchronize the overall supply chain as a continuous process and is essential for effective supply chain connectivity. While the purpose of logistical work has remained essentially the same over the decades, the way the work is performed continues to radically change. The fundamental focus of this book is integrated logistics management. However, to study logistics, a reader must have a basic understanding of supply chain management. Supply chain strategy establishes the operating framework within which logistics is performed. As will be reviewed shortly, dramatic change continues to evolve in supply chain practice. Accordingly, logistics best practice, as described in this book, is presented as a work in progress, subject to continuous change based on the evolving nature of supply chain structure and strategy. Chapter 2, Logistics, examines the renaissance taking place in logistics best practice and sets the stage for chapters that follow. At first glance, supply chain management may appear to be a vague concept. A great deal has been written on the subject without much concern for basic definition, structure, or common vocabulary. Confusion exists concerning the appropriate scope of what constitutes a supply chain, to what extent it involves integration with other companies as contrasted to integrating a firms internal operations, and how to best implement a strategy concerning competitive practices and legal constraints. For most managers, the supply chain concept has intrinsic appeal because it envisions new business arrangements offering the potential to improve competitiveness. The concept also implies a highly effective network business relationships that serve to improve efficiency by eliminating duplicate and nonproductive work. Understanding more specifically what constitutes the supply chain revolution starts with a review of traditional distribution channel practice.

To overcome challenges of commercial trading, firms developed business relationships with other product and service companies to jointly perform essential activities. Such acknowledged dependency was necessary to achieve benefits of specialization. Managers, following the early years of the industrial revolution, began to strategically plan core competency, specialization, and economy of scale. The result was realization that working closely with other businesses was essential for continued success. This understanding that no firm could be totally self-sufficient contrasted to some earlier notions of vertical integration.2 Acknowledged dependence between business firms created the study of what became known as distribution or marketing channels. Because of the high visibility of different types of businesses, the early study of channel arrangements was characterized by classification based on specific roles performed during the distribution process. For example, a firm may have been created to perform the value-added services called wholesaling. Firms doing business with a wholesaler had expectations concerning what services they would receive and the compensation they would be expected to pay. In-depth study of specific activities quickly identified the necessity for leadership, a degree of commitment to cooperation among all channel members, and means to resolve conflict. Scholars who conduct research in channel structure and strategy developed typologies to classify observable practice ranging from a single transaction to highly formalized continuous business relationships. The bonding feature of channel integration was a rather vague concept that all involved would enjoy benefits as a result of cooperating. However, primarily due to a lack of high-quality information, the overall channel structure was postured on an adversarial foundation. When push came to shove, each firm in the channel would first and foremost focus on achieving its individual goals. Thus, in final analysis, channel dynamics were more often than not characterized by a dog-eat-dog competitive environment. During the last decade of the 20th century, channel strategy and structure began to shift radically. Traditional distribution channel arrangements moved toward more integration and collaboration. Prior to reviewing the generalized supply chain model, it is important to understand why integration creates value.

Logistics Management vs. Supply Chain Management: The difference

There seems to be some confusion about the meaning of Supply Chain Management and Logistics Management. Some people use both terms interchangeably to refer to the same activity, while others know there is a difference, but cant quite explain it.

There are many definitions for both terms, depending on which source you listen to. In North America, Logistics is often associated with transportation or distribution only. In Europe, Logistics involves the entire supply chain. For those who look for clarification on this topic, here is one explanation of the difference between the two terms that we at Logistics Advice stand behind. Logistics Management is the management of the flow of goods, information and other resources, including energy and people, between the point of origin and the point of consumption in order to meet the requirements of consumers at the lowest cost possible. Supply chain management involves coordinating and integrating Logistics Management (as described above) within and among companies. Our view on these definitions is that Logistics Management involves the entire supply chain (from point of origin to point of consumption) but is often practiced at a local level (within an individual company) where Supply Chain Management specifically focuses on optimizing the flow of goods throughout the entire chain (within and among companies).

Transportation, logistics, supply chain management, materials handling, and inventory control continue to evolve. This evolution has created cross-fertilization among these functions, driven by factors both conceptualmatching demand to supplyand technologicalan enhanced ability to communicate and collaborate. This cross-fertilization has also blurred the definition of some terms. For example, is logistics the same thing as supply chain management? People working in different functional areas of logistics often define supply chain management (SCM) as it relates to what they do. A recent survey of Inbound Logistics readers supports this. Some respondents say SCM is the same old thing with a new handle, while others note it is more encompassing than logistics. Many logistics veterans believe we have progressed from transportation to physical distribution to logistics to supply chain management. By contrast, purchasing managers have evolved their thinking from purchasing management to procurement and now to supply management (SM). Some couch supply management as SCM. Others don't want to give up the term purchasing, and now refer to this functional area as purchasing and supply management. Manufacturing professionals hold yet another perception of SCM: as the task of allocating and committing resources for obtaining necessary supplies and capacity, handling, and positioning products to meet customer demands. MRP and ERP systems now address resource commitments that go beyond manufacturing to include other enterprise and supplier resources, ultimately directed to satisfying customer demands with limited and efficient use of resources.

Other departments in the company also wonder about SCM and its orientation. In marketingas well as the broader functionality that includes business and consumer research, promotions, and salesSCM addresses the needs and market potential of not only immediate customers and consumers who buy products and services, but also end users. Naturally, market research analyses of end product usage are extremely important. Many professionals perceive SCM in terms of a conceptual flow model, with goods flowing from the beginning source of raw materials to their end use. Within this context, my peers and I define SCM as "the integration of processes composed of materials, services, information, and cash within a company and in a network of companies or organizations that manufacture and deliver products and services from initial sources to end users." By its nature, SCM encapsulates inter-enterprise, cross-functional processes that target end users of products and services. It requires integrated teams who are open and trustful in their value engineering and activities analysis. Initially, logistics practitioners focus on supply chain applications that interface with immediate customers, suppliers, and intermediaries. Economic functional "activity" tradeoffs are analyzed in terms of who can best perform functions that are for the good of all trading partners. The longterm vision is inter-enterprise teams working seamlessly across all functions and activities to meet end user needs. Getting to the Core of SCM How then does SCM differ from logistics processes? Simply, SCM comprises cross-functional and inter-enterprise logistics processes. Here's how these unique processes overlap and intertwine: Demand planning and sales forecasting. Who is responsible for forecasting the needs of the supply chain? Where does demand/usage begin? These are just two questions supply chain professionals might ask when focusing on the end user or consumer. Without shared and readily available information on end user sales and demands, all other trading partnersand those within a company not directly related to end user demandare working off "derived demand" from supply chain individual enterprise sales. Within each echelon, several forecasts are alive but often without the consensus of all parties in a company, much less the entire supply chain. A company develops business forecasts and goals, as well as product/market forecasts, to achieve broad long-term financial development benchmarks. These forecasts provide a basis for resource planning, which ultimately leads to shorter-term, monthly forecasts aimed at deriving the "numbers" that drive earnings for the year. Sales and operations planning next addresses resource loading to meet two- to six-month plans for capacity use and supply planning. Finally, short-term production forecasts are needed to set production, operations, and sales schedules.

For most businesses, a key question is whether they have consensus for forecasts to drive the company. Forecasts are often based on different assumptions and metricsdollars, units, and shipments, for example. Extend this thinking to supply chain forecasting among trading partners, and a similar question arises. Is there consensus-based communication among trading partners? Often, forecasts and schedules are not shared, leading to the bullwhip effect that Dr. Jay Forrester and his MIT colleagues first discussed in the late 1950s. SCM manufacturing and operations strategies. Forecasting leads to supply chain manufacturing strategies that go beyond an individual business. Product Life Cycle Management strategies come into play when SCM addresses integrated research and process design targeted at getting products manufactured and to market as fast as possible. Processes dealing with postponement become extremely important in deciding where in the supply chain manufacturing and operations functionality are performed. Instead of taking 20 years to achieve significant market share globally, companies now establish supply chains that get product from design to key world markets in one year or less. Otherwise, ROI payback is lost. Purchasing and supply management. Suppliers need to be linked to production schedules and aware of demand throughout the supply chain. Purchasing and supply management occur at all stages of the supply chain. At each level, logisticians exercise their responsibilities to order and replenish products for their businesses from select suppliers to meet demand. Disjointed supply functions can occur anywhere in the supply chain when there is a fracture in communication. Too often, purchasing professionals order products and supplies when they know there are excessive supplies of product already in the supply chain Purchasing goes well beyond getting the best price for the product from a supplier. It's knowing where and how much inventory already exists. Supply chain logistics. Rationalizing the nodes in the supply chain and going beyond interpreting a company's assembly, manufacturing, and distribution nodal points is the ultimate vision of supply chain logistics professionals. For example, many businesses now work with their customers to justify the number of nodes for deploying inventories. They find that their customers have as much inventory in their systems as the manufacturing company, its suppliers, and intermediaries. Inventories in transit and at "dwell" points in supply chains need to be analyzed to streamline supply chain logistics. As a result, visibility of orders, supplies, inventories, and shipments is critical to supply chain planning. Reverse business and supply chain systems. An often-overlooked area in supply chain applications is reverse logistics. The recycling of automobile batteries, for example, illustrates the role of reverse business systems and supply chains that are multi-echelon and interenterprise.

An end user orientation for auto batteries has both environmental and economical advantages, increasing reusability of materials while keeping the cost of batteries low. The end result is that approximately 95 percent of the lead used in new batteries is from recycled materials. End User Metrics Businesses today need to develop and manage metrics so that they can measure order fill rates and meet managed usage. A retail store manager, for example, indicated that his inventory performance was +98 percent meaning that he gets the product he orders nearly 100 percent of the time. Yet, consumers were walking out the door with short fills on needs, returning home empty-handed or with 80 percent fill rates on the items they came to buy. Why? The store was measuring the wrong metrics. The retail merchant needs to solve consumer problems, build good relationships, and achieve high customer retention through high fill rates, low prices, and minimal end user supply chain costs. The store also needs easy in-and-out shopping with rapid payment, and fewer returns through more sophisticated consumer profiling. Supply chain management, in all its varying constructions and perceptions, is made possible by new relationships among business partners, advancements in technology, and value analysis and reengineering. These innovations continually alter the perception of SCM, especially as it relates to different logistics functions and supply chain partners.

You might also like

- Literature Review: II. Supply Chain Management Concept DefinitionDocument10 pagesLiterature Review: II. Supply Chain Management Concept DefinitionDeep SanghaviNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument11 pagesSupply Chain ManagementrahilkatariaNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument10 pagesSupply Chain ManagementAnnie CaserNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument76 pagesSupply Chain Managementsreejith_eimt13No ratings yet

- Strategic Supply Chain Management and Logistics-120626131827-Phpapp01Document15 pagesStrategic Supply Chain Management and Logistics-120626131827-Phpapp01awais04100% (1)

- SCORDocument25 pagesSCORmicuentascribd1100% (1)

- Chapter 6 - Supply Chain Technology, Managing Information FlowsDocument26 pagesChapter 6 - Supply Chain Technology, Managing Information FlowsArman100% (1)

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument8 pagesSupply Chain Managementaryan_hrsNo ratings yet

- A Framework of Supply Chain Management LiteratureDocument10 pagesA Framework of Supply Chain Management LiteratureimjaysoncNo ratings yet

- What Is Logistics - LogisticsDocument20 pagesWhat Is Logistics - Logisticsvedantpatil88No ratings yet

- Global View of Supply Chain ManagementDocument7 pagesGlobal View of Supply Chain ManagementVinay IyerNo ratings yet

- Project MangmentDocument31 pagesProject MangmentKashif Niaz MeoNo ratings yet

- Agile SC Strategy Agile Vs LeanDocument14 pagesAgile SC Strategy Agile Vs LeanChiara TrentinNo ratings yet

- Assignment Supply Chain Management BY Virupaksha Reddy.T ROLL NUMBER: 510916226 OM0003 SET-1Document12 pagesAssignment Supply Chain Management BY Virupaksha Reddy.T ROLL NUMBER: 510916226 OM0003 SET-1virupaksha12No ratings yet

- Unit 14 - Strategic Supply Chain Management and LogisticsDocument8 pagesUnit 14 - Strategic Supply Chain Management and Logisticsanis_kasmani98800% (1)

- Research ProjectDocument31 pagesResearch Projectakash sharmaNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management (Cont.) (Discussed by Video) Basic SC For A ProductDocument11 pagesSupply Chain Management (Cont.) (Discussed by Video) Basic SC For A ProductJulia ChinyunaNo ratings yet

- SCM Unit 1Document43 pagesSCM Unit 1rpulgam09No ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument25 pagesSupply Chain ManagementRizwan BukhariNo ratings yet

- Information Sharing in Supply Chain ManagementDocument6 pagesInformation Sharing in Supply Chain ManagementZahra Lotfi100% (1)

- Digital Technology Enablers and Their Implications For Supply Chain ManagementDocument16 pagesDigital Technology Enablers and Their Implications For Supply Chain Management7dk6495zjgNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Green Supply Chain Management Practices On Firm Performance: The Role of Collaborative CapabilityDocument47 pagesThe Impact of Green Supply Chain Management Practices On Firm Performance: The Role of Collaborative Capabilityadyatma taufiqNo ratings yet

- A Project On The Supply Chain Management of Newspapers and MagazinesDocument39 pagesA Project On The Supply Chain Management of Newspapers and MagazinesHector MoodyNo ratings yet

- POMDocument14 pagesPOMKiran ThapaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Digital Supply Chain of The Future - Technolog PDFDocument3 pagesIntroduction To The Digital Supply Chain of The Future - Technolog PDFCindy Christine NoveraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Role of Logistics in Supply Chains Learning ObjectivesDocument13 pagesChapter 2 Role of Logistics in Supply Chains Learning ObjectivesAshik AlahiNo ratings yet

- The Power Matrix of Supplier-Buyer RelationshipDocument32 pagesThe Power Matrix of Supplier-Buyer Relationshipselas_381983No ratings yet

- 31 Singh Mony SCM at WalmartDocument18 pages31 Singh Mony SCM at WalmartabhishekkumarweNo ratings yet

- Strategic Relation Supply Chain and Product Life Cycle: January 2014Document9 pagesStrategic Relation Supply Chain and Product Life Cycle: January 2014Tanvir HossainNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument6 pagesSupply Chain ManagementZehra Abbas rizviNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Supply Chain ManagementDocument12 pagesEthics in Supply Chain ManagementMahfoz KazolNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain & Logistic S AsianDocument9 pagesSupply Chain & Logistic S AsianAmit SinghNo ratings yet

- Role of Infarmation Technology in WalDocument12 pagesRole of Infarmation Technology in WalMukesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Class Slides - CH 7 SC MappingDocument30 pagesClass Slides - CH 7 SC MappingRafi HyderNo ratings yet

- Quality Management in Supply ChainDocument14 pagesQuality Management in Supply ChainrnaganirmitaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Supply Chain MGTDocument10 pagesStrategic Supply Chain MGTmike100% (1)

- Rfid Technology For Supply Chain OptimizationDocument2 pagesRfid Technology For Supply Chain Optimizationkoolme18No ratings yet

- Evolution of Supply Chain ManagementDocument7 pagesEvolution of Supply Chain ManagementBryanNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management: A Presentation by A.V. VedpuriswarDocument54 pagesSupply Chain Management: A Presentation by A.V. VedpuriswarSatish Kumar SatishNo ratings yet

- Careers in Logistics: What Is Logistics About?Document8 pagesCareers in Logistics: What Is Logistics About?Cidália FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Postponement Strategy From A Supply Chain Perspective: Cases From ChinaDocument26 pagesPostponement Strategy From A Supply Chain Perspective: Cases From ChinaRaajKumarNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Performance Measurement: A Case Study About Applicability of SCOR Model in Automotive Industry FirmDocument8 pagesSupply Chain Performance Measurement: A Case Study About Applicability of SCOR Model in Automotive Industry FirmMehak KhanNo ratings yet

- 5th Ed Chapter 04Document22 pages5th Ed Chapter 04Soh Herry100% (1)

- The General Principles of Value Chain ManagementDocument8 pagesThe General Principles of Value Chain ManagementAamir Khan SwatiNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain in Post COVID-19 WorldDocument1 pageSupply Chain in Post COVID-19 WorldNeeraj GargNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain System Strategy A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionFrom EverandSupply Chain System Strategy A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNo ratings yet

- W Hy Logistics ? History of Logistics:: Type of Logistics: How To Improve Your Logistics Network FlowDocument10 pagesW Hy Logistics ? History of Logistics:: Type of Logistics: How To Improve Your Logistics Network FlowAnas BouchikhiNo ratings yet

- Wal-Mart's Supply Chain Management PracticeDocument11 pagesWal-Mart's Supply Chain Management PracticeSushant Saxena100% (1)

- Impact of CSR in Supply ChainDocument13 pagesImpact of CSR in Supply ChainKesharbani NeerajNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument27 pagesSupply Chain Managementmushtaque61No ratings yet

- 5443 Global Supply Chain ManagementDocument22 pages5443 Global Supply Chain Managementdouglas gacheru ngatiiaNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain MGMT Final-105Document40 pagesSupply Chain MGMT Final-105Nilesh JetaniNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Rigor of Case Study Research in Supply Chain ManagementDocument10 pagesAssessing The Rigor of Case Study Research in Supply Chain ManagementllanojairoNo ratings yet

- Subject: Logistic Management: Course: Attempt Any Five Questions (16 Marks Each)Document11 pagesSubject: Logistic Management: Course: Attempt Any Five Questions (16 Marks Each)Sailpoint CourseNo ratings yet

- SCOR Framework 2.1 PDFDocument72 pagesSCOR Framework 2.1 PDFNurfiana Dwi AstutiNo ratings yet

- Analytics in Supply Chain ManagementDocument1 pageAnalytics in Supply Chain ManagementTushar PrasadNo ratings yet

- (201207) (TDS) Ig4848Document2 pages(201207) (TDS) Ig4848Abdelrahman AwadallahNo ratings yet

- BZ090Document3 pagesBZ090ImronNo ratings yet

- Micro Ug4 ApplicationsDocument6 pagesMicro Ug4 ApplicationsSrijita GhoshNo ratings yet

- Quality Manual: Organization ChartDocument2 pagesQuality Manual: Organization ChartmuthuselvanNo ratings yet

- Black and Decker Robotic Vacuums CaseDocument14 pagesBlack and Decker Robotic Vacuums CaseTharun ReddyNo ratings yet

- M5Document14 pagesM5Elaine Antonette RositaNo ratings yet

- PDF Strategic and Tactical Tools For e Business Supply Chain Management e Procurement - CompressDocument32 pagesPDF Strategic and Tactical Tools For e Business Supply Chain Management e Procurement - CompressDennMark CasillaNo ratings yet

- Module 1. Prelims Workshop Theory and Practice 1ADocument7 pagesModule 1. Prelims Workshop Theory and Practice 1AmanuelNo ratings yet

- OTPL - Introduction PDFDocument31 pagesOTPL - Introduction PDFAnil Kumar H CNo ratings yet

- Compiled Business PlanDocument17 pagesCompiled Business PlanClarence Abainza BalmeoNo ratings yet

- Administering Planning ModulesDocument197 pagesAdministering Planning ModulesRasel moreNo ratings yet

- Application of Porter 5 Forces To The Banking Industry by Anthony Tapiwa MazikanaDocument8 pagesApplication of Porter 5 Forces To The Banking Industry by Anthony Tapiwa MazikanaVishant KumarNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Analysis, MCQsDocument6 pagesPharmaceutical Analysis, MCQsDr. Aditi100% (1)

- Case Study BBCDocument16 pagesCase Study BBCkochanparambil abdul33% (3)

- Amazon Fulfillment ProcessDocument1 pageAmazon Fulfillment ProcessRAHUL RNAIRNo ratings yet

- Marketing Myopia by Theodore LevittDocument37 pagesMarketing Myopia by Theodore LevittFurqan HaiderNo ratings yet

- Ameya Virkud 2020PGP191Document5 pagesAmeya Virkud 2020PGP191Ameya VirkudNo ratings yet

- Adidas Marketing ExperimentDocument2 pagesAdidas Marketing ExperimentNivedkrishna ThavarayilNo ratings yet

- E3. Sample Notification of Inspection (Noi) NOI No. VLV-NOI-381 Rev. 0Document1 pageE3. Sample Notification of Inspection (Noi) NOI No. VLV-NOI-381 Rev. 0Isaac EdusahNo ratings yet

- Robotics Process Automation September 2015 v17-1Document164 pagesRobotics Process Automation September 2015 v17-1Meena Karthikeyan91% (11)

- BPM Cbok 4.0 PDF - pdf-201-250Document50 pagesBPM Cbok 4.0 PDF - pdf-201-250Eder Morales Cano100% (1)

- Chapter 6Document13 pagesChapter 6Saharin Islam ShakibNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain DriversDocument26 pagesSupply Chain DriversHaris AlviNo ratings yet

- Metal CastingDocument93 pagesMetal CastinghashimtkmceNo ratings yet

- 2.008 Metal Casting: Reading: Kalpakjian Pp. 239-316Document42 pages2.008 Metal Casting: Reading: Kalpakjian Pp. 239-316Kamal ThummarNo ratings yet

- Business Consultancy - Lecture 1Document5 pagesBusiness Consultancy - Lecture 1Daniel KerandiNo ratings yet

- Naukri MadhavBapat (26y 0m)Document3 pagesNaukri MadhavBapat (26y 0m)Amit SinhaNo ratings yet

- KPI For Operations ManagerDocument4 pagesKPI For Operations ManagerTemitope BamideleNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management - 1: End Term Project ReportDocument16 pagesMarketing Management - 1: End Term Project ReportManan GuptaNo ratings yet

- S6 - Manufacturing Engineering Design Stamping PDFDocument27 pagesS6 - Manufacturing Engineering Design Stamping PDFbrighton chapfuwaNo ratings yet