Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Final Intrmuros TDP

Uploaded by

tinea nigraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Final Intrmuros TDP

Uploaded by

tinea nigraCopyright:

Available Formats

Arellano University School of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2600 Legarda St. Sampaloc Manila, Philippines www.arellano.edu.

ph

TOURISM DEVELOPMENT PLAN IN INTRAMUROS

A Research Presented to the Faculty Committee of the School of Hospitality and Tourism Management and School of Business and Commerce

In Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Hospitality and Tourism Management

Prepared By: Sabalboro, Michael John P. Concrenio, John Mark S. Corong, Mark Louie D. Umali, Mark Eleazar M. Lecaroz, Jimlord March 2013

I.

Issues When you look at Manila today, you will be awed by how much progress it has achieved

since the olden times. But there is a place in modern Manila that still retains its original and rich culture, and that is Intramuros which is known as the oldest district and historic core of Manila, the capital of the Philippines. Known as the Walled City, the original fortified city of Manila was the seat of the Spanish government during the Spanish colonial period. During the Spanish colonial period, Intramuros served as the center of political, military and religious power of the Spaniards. Its design was based upon a star fort and it was built to protect the seat of the Spanish government from foreign invasions and raiding Chinese sea pirates. Intramuros was actually the capital and the center of almost all major activities during the Philippine-Spanish times. That is why the Philippine government decided to preserve the community within the walled city of Intramuros to make it one of the major tourist attractions in the Philippines. But these days, Intramuros is being bombarded, not by invading armies, but problems within. Plans to restore and rehabilitate the centuries-old Walled City of Intramuros are facing three obstacles which are lack of funds, informal settlers and concerns of destruction of the 15thcentury Spanish fortress. Manilas renowned Walled City of Intramuros and Fort Santiago were also included on the list of more than 200 global heritage sites in the developing world that are facing irreversible loss and damage. But the governments struggle to restore the beauty and grandeur of Intramuros through partnership with private investors is also faced with lingering opposition from those who are concerned about the destruction of the 15th-century structures. For many years, the government has been sidetracked on its plans. Private investors are hesitant to pour in their money due to the increasing number of informal settlers who continue to discourage foreign and local tourists due to safety reasons. As it is now, most of the ruins, walls,

fortifications, monuments and plazas have been virtually turned into shelters of homeless families, beggars and solvent-sniffing boys, as well as parking lots. The cost of rehabilitation and restoration of its significant landmarks require a huge amount of funds, both for the expertise in preserving the structures and the development of the sites themselves.The governments plan to revive the grandeur and put Intramuros back in the tourism-priority platform is a noble endeavor. Intramuros is indeed a priceless treasure for a country with a rich historical past.

II.

Map Location It's hard to get hopelessly lost in Intramuros, thanks to the district's orderly street plan.

General Luna (also known by its old name, Calle Real del Palacio) is the closest thing Intramuros has to a main street and gives visitors easy access to most of the major attractions, including San Agustn Church and Manila Cathedral. Follow this street all the way to its northwestern tip and you'll find yourself in front of Fort Santiago; go the other way and you'll eventually end up in Rizal Park, which is just over the border in the nearby Ermita district. If you do lose your bearings, don't panic. Keep in mind that except for a small section near the river, the entire district is surrounded by walls - so there probably isn't much of a chance that you'll inadvertently end up in the wider city beyond. A quick look at a map (and perhaps a little help from passers-by) should easily put you back on track.

III.

History Long before the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines, communities prospered along the banks of the Pasig River. One of these was Maynilad, a colony with a palisaded fort. Ruled by Rajah Soliman, a Tagalog chieftain, the citadel was a trade center for Asian goods. Peace in the thriving community was shattered upon the arrival of the Spaniards led by Martin de Goiti and later by conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legaspi. The fort was burned twice, first by the spaniards under Goiti and later the natives themselves before it was completely left to the spanish colonizers On June 24, 1571, Legaspi founded the city of Manila on the site of the old settlement. The city became the capital and seat of Spanish sovereignty in the Orient for over three hundred years. Threats of invasion by Chinese, Japanese, Dutch and Portuguese pirates prompted the construction of defenses consisting of high stone walls, bulwarks and moats. The walls stretched to 4.5 kilometers in length, enclosing a pentagonal area of approximately 64 hectares. The area consisted of residences, churches, palaces, schools and government buildings. Entry was made possible through gates with drawbridges which were closed before midnight and opened at the break of dawn. It was in this manner that the city earned the name Intramuros- meaning within the walls. Honored by King Philip II with the title Insigne y siempre Leal Ciudad

(Distinguished and Ever Loyal City), it served as the political, cultural, educational, religious and commercial center of Spains empire in the East. The riches of Asia were

gathered in the ciudad Murada or Walled City (as Intramuros was later known), and loaded on galleons in Cavite for transport to Acapulco, Mexico. But the walls did not discourage other ambitious European powers. Dutch pirates were driven off several times from Philippine waters. The British invaded Intramuros in 1762 and ruled for almost two years before returning the country to Spain. The Spanish-American War in 1898 brought the Americans to the Philippines. Intramuros was surrendered to them after a mock battle. The Filipinos began a different lifestyle with their new colonial master. Major portions of the walls including two gates were destroyed to make way for roads to Intramuros. The Japanese occupied the Philippines at the outbreak of World War II. For three years, fear and death stalked the city. Fort Santiago became a hell house where the Japanese army tortured and killed hundreds of hapless civilians and guerillas. After surviving a number of earthquakes, typhoons, fires and wars through the centuries, Intramuros took the deathblow when the Americans liberated the Philippines from the Japanese in 1945. Artillery shells reduced the walls and buildings to ashes. Thousand died during the eight-day siege. When it was over, Intramuros was a dead city. In 1946, the United States recognized Philippine independence but the city did not spring back to life. Decades after the war, it became a vast wasteland overrun by squatters and warehouses. Trucks with container vans rumbled through streets, further damaging the ruined buildings and endangering the foundations or the century-old San Agustin Church.

On April 10, 1979, Presidential Decree 1616 created the Intramuros Administration (I.A.) to undertake the restoration and development of Intramuros as a monument to the Hispanic period in Philippine history.Intramuros Administration was attached to the Department of Tourism in 1897, and was given the additional task of promoting the Walled City as a principal tour destination. Today, efforts to preserve the Walled City and revive its illustrious past are stronger than ever. The present generations of Filipinos has come to realize its historical value. As in the days of our forefathers, Intramuros is a priceless treasure to be shared with the world.

IV.

Tourism Mapping Built 1.Fort Santiago One of the oldest fortifications in Manila. Built in

1571, on the site of the native settlement of Rajah Soliman. First fort was palisaded structure of logs and earth. Destroyed in the Limahong attack in 1574. Stone fort built between 1589 and 1592. Damaged in the 1645 earthquake. Repaired and strengthened from 1658 to 1663. Became the headquarters of the British occupation army from 1762 to 1764. Repaired and renovated in 1778. Former headquarters of the Philippine Division of the U.S. Army. Occupied by the Japanese Military in 1942. Where hundreds of civilians and guerillas were imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Destroyed in the Battle of Manila in 1945. Used as depot of the U.S. Transportation Corps before turnover to the Philippine Government in 1946. Declared Shrine of Freedom in 1950. Restoration and maintenance of the fort began in 1951 under the National Parks Development Committee. Management was turnover to the Intramuros Administration in 1992.

2. Palacio Del Gobernador State residence of the Governor General of the Philippines. First palace or Palacio Real constructed in 1599 near Plaza De Armas in Fort Santiago. Destroyed in 1645 earthquake. Moved to present site. Became GovernorGenerals residence and office as well as the Real Audiencia (Supreme Court). Reconstructed in 1733 and 1747. Damaged in the 1771 earthquake. Spanish-type faade added in 1850. Destroyed in 1863 earthquake. Abandoned when Governor-General moved to Malacaang. Used as an air-raid shelter during World War II where 80 male civilians were massacred in 1945. Present building constructed in 1976 to house government offices.

3. Postigo Del Palacio Built in 1662, Led to the palaces of the GovernorGeneral and the Archbishop of Manila. Original gate located several meters to the left. Renovated in 1782. National hero Jose Rizal passed through this gate from Fort Santiago to his execution site at Bagumbayan in 1896. Damaged during Battle of Manila in 1945. Restored in 1968. Bridge excavated and restored from 1982 to 1983.

4. Puerta de Sta. Lucia Built in 1603, this was one of the original entrances to the Walled City. Underwent improvements in the late 18th century. Favored route to Malecon Drive outside walls. Destroyed during Battle of Manila in 1945. Side chambers restored in 1968 and gate in 1982.

5. ECJ Building The Casa Nueva or the Provincial House of the Augustinian Order. Built in 1895 and connected to San Agustin convent by an ornate covered walkway over Calle Real. Destroyed by fire in 1932. Two-story building constructed to house Adamson University in 1939. School funded in 1932 by George and Lucas Adamson as a technological school in Sta. Cruz Manila. Used as army barracks during the Japanese occupation. Destroyed in 1945. ECJ Building erected in the 1980s with a faade patterned after the Provincial House.

6. Baluartillo de San Jose A tunnel-like passage built in with a drainage canal emptying out into the moat, its primary use was to transport ammunitions to Reducto de San Pedro. The site was known as No. 1 Victoria St., when it served as Gen. Douglas MacArthurs headquarters in 1941.

7. Reducto de San Pedro This is an independent pentagonal structure built outside the walls. It had its own stockpile of cannon balls deposited in recessed ledged at the entrance.

8. Bagumbayan Light and Sound Museum The centerpiece project of the Visit Philippines 2003campaign. This lot was the former site of the convent of the nuns of the Beatro de la Compaa de Jesus now the Religious of the Virgin Mary. Considered as a major tourist attraction being the first of its kind in Asia. The Museum showcases Philippine

history in a nutshell focusing on Rizals heroism and martyrdom. 9. Baluarte de San Diego Designed and built by Jesuit priest Antonio Sedeo from 1586 to 1587. It is one of the oldest stone fortifications in Intramuros. Began as a circular fort called Nuestra Seora de Guia, renovated in 1593 to join the walls of the city. Fort fell in disrepair. New baluarte completed between 1643 and 1663.

Resembling an ace of spades, it housed a foundry during the 18th century. Breached by British forces with cannon fire in 1762. Restored after the British occupation but damaged during the earthquake of 1863. It was then condemned by the Spaniards. Totally destroyed during the Battle of Manila in 1945. Restored from 1979 to 1992. 10. Puerta Real Built in 1663. Used exclusively by the Governor General for state occasions. Original gate at right side of the Baluarte de San Andres and faced the village of Bagumbayan. Destroyed during the British Invasion in 1762. Old gate walled in and chambers converted into powder magazines. Present Puerta Real and ravelin contrasted in 1780.

11. Revelin de Real de Bagumbayan Ravelin converted into Manila Aquarium during the American period. Used as prison cells and barracks during Japanese occupation. Damage in the Battle of Manila in 1945. Restore in 1969 and additional worked made in 1989. Ravelin bridge excavated and restored in 1982. The Manila Aquarium was revived after the war and maintained until in 1983.

12. Baluarte de San Andres Built in 1603. Designed to protect the old Puerta Real and reinforce southeastern part of Intramuros. Reconstructed in 1733 with the addition of s bombproof arsenal for gunpowder, a watchtower (garita) and soldiers barracks. Also called Baluarte de San Nicolas or Carranza. Destroyed during British siege of Manila in 1762.

Rebuilt and modified after the British occupation. Damaged during the Battle of Manila in 2945. Restored in 1987. 13. Revellin de Recoletos Built in 1771. Named after the Recoletos Church nearby. Also known as Revellin de Dilao. Built to

strengthen the defense of the curtain wall between Baluarte de Dilao and Baluarte de San Andres. Original entrance closed when revelin was converted into a garden in 1940. Named Aurora Gardens honor of the wife of Commonwealth President Manuel L. Quezon. Damaged during the Battle of Manila in 1945. Restored in 1969 and again in 1986. 14. Baluarte de Dilao Built in 1592 as part of the original fortifications. Also known as San Lorenzo, San Francisco, San

Francisco de Dilao or simply Dilao. Named after the Japanese suburb it faced across the city. Enlarged in 1662 following threats invasion by Chinese

pirates. Damaged after the British attack on Manila in 1762. Repaired and strengthened in 1773. Damaged during the Battle of Manila in 1945. Restored in 1984. 15. Puerta del Parian Named after Parian de arroceros across the city where Chinese merchants lived. Built in 1593. One of the earliest entrances to Intramuros. Became official entrances of the Governor General in 1764, after destruction of Puerta Real during the British invasion. 16. Revellin del Parian Ravelin built in 1603 following Chines uprising. Used as defense line between the curtain walls of Baluarte de San Andres and the Parian Gate. Vaulted chambers built in 1739 to house soldiers supplies. Entire defense work completed in 1782. Gate and ravelin severely damged in 1945. Restoration begun in 1967 and completed in 1982. 17. Baluarte de San Gabriel Built in 1593, this was the walled citys most important defense on the north that protected

the riverside. Rampart cannons overlooked the parian in Binondo. Site of the first parian in manila and former site of the hospital de San Gabriel. Hospital founded in 157 by the Dominican Fathers for Chinese populace. Destroyed by fire government for security reasons. Moved to binondo. Closed in 1774. Baluarte de San Gabriel underwent renovations in the 18th century. Destroyed in 1945 during the batlle of manila. Restored in 1989 18. Puerta de Isabel II Opened in 1861. The last gate to be built in intramuros. Part of route of tranvia (streetcar) in the 19th century. Damaged during battle of manila in 1945. Restored in 1966. Statue of Queen Isabel II originally unveiled at plaza arroceros. Removed and stored in 1868. Place in front of malate church from 1896 until 1970. Moved to present site in 1975. Chambers built in 1837 extending from Baluarte De santo Domingo to baluarte de San Gabriel. Used as military medical quarters and store house. Sections demolished by American engineers in 1903. Damaged during battle of Manila in 1945, only 15 chambers remain intact. 19. Adauna (Customer House) Designed by tomas cortes and built from 1823 to 1829. Damaged in the 1863

earthquake Demolished in 1872.New building erected from 1874 to 1876. Housed the Customs offices, the Intendencia General de Hacienda (Central Administration), the Treasury, as well as the new Casa de Moneda (Mint). Building left to the Intendencia and the Treasury after the Customs moved to Port Area. Damaged by Japanese bombs in 1941 and American artillery in 1945. Became offices of the Central Bank of the Philippines, the National Treasury and the Commission on Elections successively. Destroyed by fire in 1979. Faade restored by National Archives in 1978. 20. Plaza de Sto. Tomas Lot originally purchased by the Dominican Order in 1627 for their cemetery and garden. Bought by city government in 1861 as a public plaza. Given to the University of Santo Tomas in 1879. Bronze statue of U.S.T. founder Archbishop Miguel Benavides erected in 1891. Original monument transferred to present campus along Espana Street after the war. Replica installed in 2002. 21. Ayuntamiento (Casas Consistoriales) Seat of City Council of Manila, first structure built from 1599 to 1607. Severely

damaged in the earthquakes of 1645 and 1658, demolished to make way for a new building. Second building constructed in 1735. Destroyed in 1863 earthquake. Reconstruction by military Engineer Eduardo Lopez Navarro begun in 1879 and completed in 1884. Became headquarters of the 8th U.S. Army Corps in 1901, site of sessions of the first Philippine Assembly in 1907 and Philippine Legislation in 1935. Housed the offices of the Bureau of Justice and Supreme Court during the American and Commonwealth Period. Destroyed in the Battle of Manila in 1945. Reconstruction to house Bureau of Treasury Underway. 22. Plaza de Roma Formerly called as Plaza Mayor. Converted into a park in 1979. Renamed Plaza Mckinley after U.S President William Mckinley in 1901. Renamed Plaza de Roma in 1961 to honor Sacred College of Cardinals in Rome following elevation of first Filipino cardinal, Rufino J. Santos.Bronze monument to Carlos IV of Spain erected in 1824 as a tribute for the introduction of smallpox vaccine in the Philippines. Fountain built in 1886, statue replaced by Gomburza monument in the 1960s. Statue returned in 1981. 23. Manila Metropolitan Cathedral

This is the eight structure to rise on this site. The first cathedral was built on nipa in 1571 and was razed by fire in 1571. The second was made of stone and mortar in 1951 but was destroyed by earthquakes in 1599 to 1600. The third was built in 1614 and was again wiped out

by earthquakes in 1621 and 1645. The fourth was constructed from 1654 to 1681, damaged by the typhoons and earthquakes, and subsequently demolished in 1751. The fifth was inaugurated in 1760 and destroyed by the earthquake in 1863. The seventh was inaugurated in 1879, damaged by the 1880 earthquake and totally destroyed in the 1945 Battle in Manila. The present cathedral completed in 1958 was elevated to the rank of Pope John Paul II in 1983. It is officially named basilica of the Immaculate Conception. 24. Bahay Tsinoy (Kaisa Heritage Center) A museum that showcases the tangible imprints and lasting influence of the Chinese whose presence in the Philippines dates back long before the European sought alternate routes to the Moluccas.The museum holds lifelike dioramas depicting the lives of the early Chinese maps and annals. Interesting items on display are trade wares brought by the Chinese, rare coins and ceramics unearthed from archeological excavations in the Philippines, antique religious, images, furniture, farm implacements, household items and a replica of a sampan(Chinese sailboat). 25. Plazuela De Santa Isabel

Made part of Santa Isabel College which lacked an open space characteristic of Spanish buildings. Empty lot called Sampalucan along Calle Anda joined to enlarge plazuela in the 18th century.Restored in 1983. Monument dedicated to the non-combatant victims of the last war erected in 1995 by Memorare Manila 1945. 26. San Agustin Church and Convent San Agustin Church is the oldest church in the Philippines. Known as the Church of Saint Paul, the first church of the Augustinian order was built in 1571. Destroyed by Chinese pirates in 1574. Rebuilt a year later. Venue of the First Diocesan Synod in 1581. Burned in 1583. Third church destroyed by fire in 1586. Fourth church made of stone was designed by Juan Macias and built from 1587 to 1604. Looted during the British invasion in 1762. Terms of surrender of Manila to the Americans were discussed in the vestry in 1898.Damage in the battle of Manila in 1945. Repaired after the war. Became the site of the first Philippine Plenary Council in 1953. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. 27. Plaza San Luis Complex Named after one of the barrios of old Intramuros, this is a cultural-cum-commercial complex of nine houses representing designs of Philippine-Hispanic architecture.Aside from gift and specialty shops, a fine dining restaurant and a hotel, the complex features Casa Manila, a museum showing the affluent lifestyle at

the turn of the 20th century. Displayed are unique and valuable artifacts from the Intramuros Administration Museum Collection. V. Statement of Significance The plans of the Intramuros Administration is to redevelop Manilas tourism gem. With their new approach to involve the stakeholders especially informal settlers even in the planning stages. What the researchers think is lacking a campaign for people to really appreciate the significance of Intramuros. If you ask people, even those living in Manila, on how they see Intramuros, a lot of them would sadly tell you that it is just an old place inhabited by a lot of ghosts who died in the war. The youth, on the other hand, find it irrelevant in their lives simply because they were not prodded to go beyond the idea of it being just a staple part of their field trip itineraries. That explains why they dont treat it well. If only they realize how amazing it is to still have a historical district that can still be revived, they will respect it more and help in its renaissance. Intramuros Administration should partner with advertisers or marketers to develop a campaign that can certainly make people realize the significance of the place. This should be done in parallel with their reconstruction efforts so that by the time they finish it, there will be a market ready to enjoy and fight for this great heritage. We are thinking that this campaign should be able to do what Its More Fun in the Philippines campaign did to Filipinos: by providing them with the single best answer why Intramuros should be saved and cherished. This paper also intends to explore the downsides and benefits of the place to clearly show and critically analyze the development that has been formed with the peoples effort in developing the walled city.

VI. SWOT Analysis A. Narrative of existing tourism program Squatters Another option which may be taken in the event that squatters could not be relocated interim period that the tourism zone is being developed, would be to conduct massive community organizing and awareness-rising schemes which would seek to integrate these residents into activities, both social and economic, that the zone will generate. In so doing, these residents would realize the value of such development in their area and would assume some responsibility for ensuring that the grounds and facilities are well-maintained. Training programs, value formation centers and skills development will be made available to educate and develop the skills of the squatters. The Samahang Maralita ng Intramuros, Samahang Mahihirap na Magkakapatid and Kapitbahayang Samahan are the existing organization that can helped formulate the order of policies for the squatters residing the Intramuros. These dialogues will serve as sources of guidelines and basis for the selection of qualified beneficiaries. Those who do not qualify maybe relocated to government relocation sites. Coordination with government agencies such as the NHA,PCUP and PEA maybe obtained in the realization of this endeavor.

B. SWOT Analysis STRENGTHS Because of its old structure tourist want to see the old manila.

WEAKNESSES Some of the structure inside are very old it is prone to danger. Lack of fund to restore and

Famous because it is a place for the heritage in manila.

rehabilitate the centuries-old Walled city.

OPPORTUNITIES Restoration of the heritage sites might help boost the tourist visits in the area. Constructing of Art galleries and high tech museums that will help promote the historical significance of Intramuros.

THREATS Modernization: Although much of the modern development that has changed the face of Manila has occurred outside the walls of Intramuros, several major chains have opened outlets inside the fortress walls, including Starbucks and

McDonalds. Additionally, the old moats that originally surrounded Intramuros have since been filled and converted into a golf course. There is rampant speculation that the city wishes to capitalize on Intramuros real estate potential, replacing the heritage and history with high rises and malls.

Concerns have been voiced over the years about the appearance of Intramuros; the interior has often looked shabby or in poor condition, with poor lighting in many dark areas of the city. As a result, administration is worried that tourists will steer clear of the heritage site due to safety concerns. If nothing is done to properly assert Intramuros right to preserve its rich heritage, there is a strong likelihood that it will be soon overrun by rampant commercialism. If indeed this happens, the efforts to rebuild this jewel of Manila after its destruction in World War II will have been in vain.

C. Evaluation of Tourism

As part of the efforts to generate tourist interest in Intramuros, and as an Integral part of community-building through the promotion of social interaction among Intramuros residents, the Intramuros Administration, in collaboration with the barangay councils, local organizations and educational institutions within the district, should endeavor to revive religious/cultural events that have in the past been staple fare of Intramuros community life. These include processions, visita iglesia, santacuzan, and novenas. In addition are other activities which can be regularly conducted through the sponsorship of government agencies and private corporations including street plays, concerts and cultural shows. VII. Guiding Principles General Policies Section 1. General Policies. The administration hereby adopts the following policies to govern the exercise of its planning, restoration and regulatory functions in Intramuros . 1. Planning and Development efforts of the government and the private sectors shall be synchronized with the promotion of archeological and restoration objectives, and they shall conform to the approved Development Plan for Intramuros and these Rules . 2. All efforts at planning and restoration shall be directed toward insuring that the general appearance and architecture of buildings and structures with in Intramuros shall conform to the Philippine colonial Architecture of the 1890s. for this purpose, development shall be undertaken in accordance with provisions of these rules affecting, among others, the height, bulk an architectural design of buildings. 3. Development of properties by private individuals and entities and Government agencies shall be undertaken only after a development clearance has been issued by the Administration.

4. In implementing the Intramuros Plan and in enforcing these rules, the Administration shall respect personal and property rights. Thus, shall resort to expropriation only for specifically approved projects. For this purpose, it shall exert all efforts toward arriving at negotiated purchases and encouraging donation by the private sectors of their properties which would be needed for Government-approved projects in Intramuros. 5. The Administration shall give full encouragement and support to the development of private properties by extending technical and other forms of assistance, including incentives and financial grants.

VIII. Tourism Development Plan Objectives Intramuros Administration, the government agency given the authority to oversee the historic district, has formulated objectives which reflect their desired preservation and restoration framework. These objectives are the following: The urban life of the 1800s particularly in the Old Manila which was Intramuros must be reflected and experienced in the ambience, building envelopes and landscape of the district. The activities and functions of the building interiors must respond to the most technologically appropriate and contemporary physical ambience in urban functions and social communications. The implementation and administration of the area shall operate not as an autonomous zone but one with a special mandate with cooperative and

necessary linkages with the local government and Metro Manila Authority. Proposals of the urban development and infrastructure shall take into consideration the programs and activities of the restoration architects in Intramuros. The relevance of most objectives outlined above has not changed. However, present conditions require a much wider perspective and more flexible approach in the urban planning approach to Intramuros so as to be responsive to existing conditions and emerging trends. As articulated by the present Intramuros Administration, their major concerns are: To bring back people who will reside, work and delight in the old city center. To make Intramuros as a major tourist destination, representative of the Philippine culture and history. To preserve and enhance local culture, art, monuments and other natural and man-made tourist resources and protect them from overcommercialization and over-exploitation.

A. Organizational Structure of Tourism Responsibility Center

The organizational structure of the Intramuros Administration is directed by the Board of Administrators whose members are comprised of the Secretary of the Department of Tourism, Mayor of the City of Manila, the Eexecutive Director of the National Historical Intsitute, the Administrator and such persons that the President may

designate. At present, the Intramuros Administrator recommended the General Manager of the Philippine Tourism Authority to be part of the Board of Administrators. The executive officer of the Intramuros is the Intramuros Administrator who have the same qualifications, privileges, and rank of a Deputy Secretary. The Board of Administrators are responsible for the policies and activities of the Administration. The Administrator reports to the Board and be delegated such authority as the Board may decide. The Bids and awards committee review and recommend action on bids or proposals submitted regarding construction or restoration work contracts, labor or service contracts, supply of construction materials, office supply and equipment and other related matters. The present Intramuros Administration is composed of seven divisions whose functions are as follows: A. Urban Planning Division The Urban Planning Division is Responsible for the preparation, updating and implementation of the Intramuros Urban Development Plan including the formulation of policies, guidelines and regulations covering zoning, land use, construction and renovation; issuance of construction and building permits; inspection and monitoring of construction projects and renovation of work; determination of allowable uses of land and buildings; planning of traffic, water, sewerage, power and other utilities and the extension of general architectural assistance to private parties applying for permits to construct and renovate.

B. Walls and Fortifications The Walls and Fortifications Division plans and undertakes actual restoration, construction, landscaping and maintenance work related to the walls, moat, ravelins and other components of the Intramuros fortifications, the plazas and open spaces and other assigned projects. It undertakes and is

guided by archaeological findings, documentary research, and other pertinent work. Its responsibility covers street repair, maintenance and illumination of the walls and its fortifications. The Division is likewise responsible for contract administration, including preparation of bid documents, work schedules, inspection, acceptance of work and preparation of recommendations for payment of work undertaken and supervised by the Division. C. Museum Division The Museum Division is responsible for the organization of museum exhibits whether it be temporary or permanent. It coordinates with the National Historical Institute with respect to Fort Santiago and the Rizal Shrine. As part of its basic functions, the Division is responsible for the conservation, accession and cataloguing of exhibit items, and maintenance of security of the exhibits and exhibit halls. D. Festivals and Events Division The Festivals and Events Division is responsible for the public relations and information program, the preparation and implementation of performing arts activities in Intramuros particularly the Puerta Real Performing Arts Season, the design and implementation of campaigns for donations and general support to Intramuros projects and the design implementation of guided tours. E. Business Division The preparation and evaluation of commercial feasibility and administration of commercial activities undertaken by or under the auspices of the Intramuros Aministrationshall be under the jurisdiction of the Business Division. F. Research and Publication Division The research and Publication Division, undertakes research work on architectural, historical, cultural, military and other areas that may be of use to the other Divisions. It is responsible for the Intramuros

Publication Program and coordinates research work with the National Archives, the National Library and other scholarly institutions.

G. Administrative Division The Administrative Division is responsible for the Internal Administrative functions of the Intramuros Administration, including property, records, personnel, and general services. Provision of general financial support services, including budgeting, accounting, cash management and procurement are also their function.

B. Programs Side Car/ Kalesa Every side car and kalesa should have their particular station that can be easily access by the tourist so that it will never be hard for them to travel within the vicinity of Intramuros. Art Exhibit Art exhibit should be conducted every weekend so that the tourist and even the residence can see the art work. Specific shop for vendors All vendors should have one particular shop in order to promote the products that they sell so that the tourists know where to buy the souvenir items of Intramuros. Livelihood program for the informal settlers that resides in the Intramuros. Informal settlers should be the producer of the products for the historical places and the kids should have an intermission number so the tourist will be entertain.

Signages and maps for every historical landmarks. Directory and maps in every historical landmark so that tourist can easily identify where they are and where to go. Campaigns and promotion to boost the tourist visits in Intramuros Intramuros Administration should coordinate to the school near the vicinity of Intramuros like Mapua, Lyceum, PLM, Letran, PNTC in order to educate the students the historical significance of Intramuros that are now being taken for granted.

IX. Conclusion & Recommendation Intramuros, among the sites singled out by the Global Heritage Fkabund, requires assistance for it to take full advantage of its unique heritage qualities as a resource for national and community development. However, Intramuros exists on various levels, therefore the assistance it needs goes beyond financial. It is a national monument, symbol of the Filipinos Spanish-colonial heritage; it is also a tourism and educational destination, and an urban center where people study, live and work. Intramuros Administration has done admirably. It has restored and rehabilitated Fort Santiago; completely reconstructed the fortifications damaged by World War II; faithfully reproduced early 19th-century colonial architecture at Plaza San Luis; and has enforced building regulations to maintain the period ambiance of Intramuros. Other government agencies have contributed to Intramuros as well. Soon to finish is the reconstruction of the Spanish-colonial building, the Intendencia, which will serve as the offices for the Department of Finance. Soon to start is the reconstruction of the Aduana to be the future National Archives. Restoration and rebuilding Intramuros as a historic monument, already

achieved by the Intramuros Administration, provides the building envelope, or the hardware that is incomplete without the software that gives it life. Intramuros should live again. Software will make that happen. Heritage should come alive. Intramuros should reclaim its forgotten

significance to the Filipino nation. Visiting the Walled City should be a fun learning experience. A balance should be arrived at among the heritage, tourism, education, community and development aspects of Intramuros. Students, businessmen and office workers, the handful of permanent residents, and the informal residents who form the fragmented Intramuros community are yet to realize the significance of Intramuros and to fully participate in its renaissance which will bring them not only economic benefit but pride of place. The Intramuros renaissance has begun. The Intramuros Development Plan, supported by the Department of Tourism, has pointed out interrelationships among parallel activities that must take place: tourism, heritage conservation, education, community and economic development. What the development plan takes is a holistic view of Intramuros, developing both hardware and software together. For hardware, it looks in detail at how to rebuild Intramuros to achieve maximum benefit for its landowners or to attract the appropriate commercial development while rigorously maintaining the districts special heritage qualities.For software, it establishes community participation in tourism, heritage and economic programs, as well as educational and public-awareness programs and special events. For informal-settler community development, Intramuros Administration has partnered with Gawad Kalinga.Global Heritage Fund, headquartered in Palo Alto, California, is looking forward to participating in the Intramuros renaissance, to be part of the concerted effort to bring Intramuros back to life through assisting in the planning process, streetscape development, community programs and partnering with Gawad Kalinga for community development.With funds raised from international donors, Global Heritage Fund provides

counterpart funding to the existing budget allocated by the Department of Tourism, Intramuros Administration, Department of Public Works, and Public-Private Partnership projects, to achieve sustainable conservation of Intramuros as a vibrant urban-heritage area. When working with heritage, there is always a sense of urgency, because once heritage vanishes, it is gone forever. With the element of urgency always above the heritage professionals head, all sites are seen as endangered.

X. Reference Philippines Department of Tourism. 2008. Available: www.tourism .gov.ph/ Santiago, Asteya M. 2003. The Restoration of Historic Intramuros A Case Study in Plan Implementation. Quezon City: School of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Philippines, and Planning and Development Research Foundation, Inc. (PLANADES). Steinberg, Florian. 2007. Sector Note: Revitalization of Historic Inner-City Areas in Asia. Manila: Asian Development Bank. Task Force on Human Settlements. Project Profile. 1974. The Vision of a New Society. Quezon City: Task Force on Human Settlements. Task Force on Human Settlements. Project Profile. 1975. Quezon City: Task Force on Human Settlements. Torres, Jose Victor Z. 2005. Ciudad Murada: A Walk Through Historic Intramuros. Manila: Intramuros Administration and Vibal Publishing House, Inc. Villadolid, Alice Colet.2000. Filipinos - A Century Back and Forward. Manila: Paragon Printing Corp. Zaragoza, Ramon Ma. 1990. Old Manila. New York: Oxford University Press.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT The researchers wishes to express their deepest sense of gratitude and sincere appreciation to all those people who contributed to the completion of this research. First and foremost, to the Lord Almighty for giving us the knowledge, strength, courage, patience and providing us the spiritual grace to carry on working with this study. To our beloved parents, no words of gratitude can be considered sufficient to express their love and respect who not just only gave their love, understanding and patience but also their moral and financial support. Lastly, to Ms. Sandra Barbara for her exemplary guidance, monitoring and constant encouragement throughout the course of this research. The blessing, help and guidance given by her time to time shall carry us a long way in the journey of life on which we are about to embark.

You might also like

- Puerto Princesa SWOT Analysis - Top Eco City PhilippinesDocument11 pagesPuerto Princesa SWOT Analysis - Top Eco City PhilippinesAbe BenitoNo ratings yet

- Swot 1Document3 pagesSwot 1Clyde SalvaNo ratings yet

- Casimiro's Marketing PlanDocument22 pagesCasimiro's Marketing PlanGina BallNo ratings yet

- Impacts of The Newly Established Sky Ranch Pampanga To TheDocument2 pagesImpacts of The Newly Established Sky Ranch Pampanga To TheLhay de OcampoNo ratings yet

- Tourism in Caraga Region: An Economic DriverDocument150 pagesTourism in Caraga Region: An Economic DriverRhea CarampatanaNo ratings yet

- Research FinalDocument59 pagesResearch FinalKaren Joy Torres100% (1)

- Case StudyDocument17 pagesCase StudyShanaia BualNo ratings yet

- El Hogar Filipino Historical ResearchDocument15 pagesEl Hogar Filipino Historical ResearchVinson Pacheco Serrano33% (3)

- Importance of Rizal Park, Calle Crisologo and Leyte Landing MonumentDocument4 pagesImportance of Rizal Park, Calle Crisologo and Leyte Landing Monumentgrace garciaNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez Rizal TourismDocument5 pagesRodriguez Rizal TourismSharmaine Lizsil Reformina GarciaNo ratings yet

- Thesis CathyDocument6 pagesThesis CathyEclipse Cruz0% (1)

- Report (Lesson 5)Document6 pagesReport (Lesson 5)Sheila Rose Estampador100% (1)

- PR Plan On Rizal ParkDocument6 pagesPR Plan On Rizal ParkLawrence Tanquilut50% (2)

- Segmenting Tourist Motivation in Rizal Park-A Factor AnalysisDocument13 pagesSegmenting Tourist Motivation in Rizal Park-A Factor AnalysisGemae MatibagNo ratings yet

- A. Introduction On Best and Hidden Tourist Attraction 1. Brief BackgroundDocument8 pagesA. Introduction On Best and Hidden Tourist Attraction 1. Brief BackgroundGeojanni Pangibitan100% (1)

- Gelvez, Nuelle S. THESIS 1 - FINAL REQT.Document146 pagesGelvez, Nuelle S. THESIS 1 - FINAL REQT.Ellie San Jose Gelvez100% (2)

- PRESERVING HISTORY AND CULTUREDocument17 pagesPRESERVING HISTORY AND CULTUREElisha XDNo ratings yet

- Within The Walled CityDocument21 pagesWithin The Walled CityArrei LopezNo ratings yet

- PintoDocument8 pagesPintoblader johnNo ratings yet

- The La Mesa Eco ParkDocument3 pagesThe La Mesa Eco ParkJan DrakeNo ratings yet

- Agree Tourism ThesisDocument57 pagesAgree Tourism Thesisnathan brionesNo ratings yet

- ArRM - El Hogar Filipino BuildingDocument27 pagesArRM - El Hogar Filipino BuildingEddielyn Ogdang0% (1)

- Manalaysay JPT Thesis With Approval PDFDocument103 pagesManalaysay JPT Thesis With Approval PDFTheresa Marie PrestoNo ratings yet

- Exploration StageDocument4 pagesExploration StageLaarni ObatNo ratings yet

- Improving PH MaritimeDocument7 pagesImproving PH MaritimeHonie CastanedaNo ratings yet

- Solaire Manila Final OutputDocument28 pagesSolaire Manila Final OutputRoy CabarlesNo ratings yet

- Case Study Villa Escudero FinalDocument13 pagesCase Study Villa Escudero Finaljhessy capurihanNo ratings yet

- Eco-Cultural Historical Tourism in Mintal, Davao CityDocument41 pagesEco-Cultural Historical Tourism in Mintal, Davao CityRoxzen Valera ColladoNo ratings yet

- Vision MandateDocument7 pagesVision MandateJade Sanico BaculantaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Palay Festival On Income of Local Businesses FOR PRINTDocument39 pagesImpact of Palay Festival On Income of Local Businesses FOR PRINTDarwin AniarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document10 pagesChapter 1enaNo ratings yet

- Political: Chapter 2 External AnalysisDocument5 pagesPolitical: Chapter 2 External AnalysisDaniel SumalinogNo ratings yet

- RRL 2Document20 pagesRRL 2Reigneth VillenaNo ratings yet

- Local Residents' Views on Tourism Development in Tanay RizalDocument16 pagesLocal Residents' Views on Tourism Development in Tanay RizalMhicaella padrigaNo ratings yet

- Final Defense - Singkaban FestivalDocument67 pagesFinal Defense - Singkaban FestivalSillano Eina MAeNo ratings yet

- Shakuntala Activity (Creating Speech Balloons) PDFDocument8 pagesShakuntala Activity (Creating Speech Balloons) PDFAngela GlitterNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Tourism Impact Case StudyDocument6 pagesIndigenous Tourism Impact Case StudyLaurenceCruanGonzalesNo ratings yet

- Background of the Study on Canigao Island Resort RedevelopmentDocument5 pagesBackground of the Study on Canigao Island Resort RedevelopmentAlvin Yutangco0% (1)

- Palawan MuseumDocument9 pagesPalawan MuseumKia BaluyutNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-3 Basco Batanes AirportDocument44 pagesChapter 1-3 Basco Batanes AirportLance Alviso100% (1)

- Industry Paper On The Activities of Amusement Parks and Theme Parks in The PhilippinesDocument14 pagesIndustry Paper On The Activities of Amusement Parks and Theme Parks in The PhilippinesHeina LyllanNo ratings yet

- QCMC Case StudyDocument30 pagesQCMC Case StudyJanna Marie Pajo25% (4)

- Souvenir Shop RealDocument167 pagesSouvenir Shop RealJoanne TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Thesis FULLDocument81 pagesThesis FULLMark Jhones Licardo100% (2)

- SplashIsland ResearchDocument19 pagesSplashIsland ResearchRussel TalastasNo ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis Municipality of Liloan, CebuDocument9 pagesSWOT Analysis Municipality of Liloan, CebuSEREN TADUYONo ratings yet

- Star City MARKSEVDocument53 pagesStar City MARKSEVDarwyn Mendoza100% (3)

- A Study On Resident's Perception For Conservation On The Historic Structure in Malolos, Bulacan: The Barasoian ChurchDocument27 pagesA Study On Resident's Perception For Conservation On The Historic Structure in Malolos, Bulacan: The Barasoian ChurchDanicamae EbdaneNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of The Ecotourism Sector in The Municipality of OcampoDocument9 pagesAn Assessment of The Ecotourism Sector in The Municipality of OcampoNerwin IbarrientosNo ratings yet

- Philippines Sports Tourism Strategy 2007Document68 pagesPhilippines Sports Tourism Strategy 2007Beeyong Sison75% (4)

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument5 pagesReview of Related LiteratureRobilyn Ann BurielNo ratings yet

- Is Our Contemporary Architecture More Western or FilipinoDocument3 pagesIs Our Contemporary Architecture More Western or FilipinoMarianne Sheena Sarah SablanNo ratings yet

- Malolos Public MarketDocument2 pagesMalolos Public MarketJeonAsistinNo ratings yet

- Agri Siituational Analysis of ZambalesDocument33 pagesAgri Siituational Analysis of ZambalesCatherine ManaloNo ratings yet

- Pasalubong Center Business Plan: Haven't Found The Relevant Content? Hire A Subject Expert To Help You With PasalubongDocument22 pagesPasalubong Center Business Plan: Haven't Found The Relevant Content? Hire A Subject Expert To Help You With PasalubongEGUIA, MARY SHENIETH M.No ratings yet

- Bonifacio Global City Case StudyDocument5 pagesBonifacio Global City Case StudyRinzie Luyao0% (2)

- Swot AnalysisDocument5 pagesSwot AnalysisHoneyNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of IntramurosDocument3 pagesA Brief History of IntramurosKarla EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Brief Introduction: British OccupationDocument2 pagesBrief Introduction: British OccupationgabbieseguiranNo ratings yet

- BiotechDocument14 pagesBiotechjasmelsieNo ratings yet

- TS Circ02 2015 PDFDocument22 pagesTS Circ02 2015 PDFAnonymous 9NlQ4n2oNo ratings yet

- Action PlanDocument7 pagesAction Plantinea nigra100% (2)

- Application Letter To NDP 2016Document2 pagesApplication Letter To NDP 2016tinea nigra50% (2)

- Schedule NG MR - TDDocument4 pagesSchedule NG MR - TDtinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Road Map AgnagaDocument2 pagesRoad Map Agnagatinea nigraNo ratings yet

- BHB ListDocument7 pagesBHB Listtinea nigraNo ratings yet

- AmoebiasisDocument11 pagesAmoebiasistinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Millennium Development GoalsDocument5 pagesMillennium Development Goalstinea nigraNo ratings yet

- 01 - Introduction To MLGP PDFDocument29 pages01 - Introduction To MLGP PDFtinea nigraNo ratings yet

- IHSS101 PartII PDFDocument100 pagesIHSS101 PartII PDFtinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Smadav 2016 KeyDocument1 pageSmadav 2016 Keytinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Smadav 2016 KeyDocument28 pagesSmadav 2016 Keytinea nigraNo ratings yet

- The Imci StrategyDocument7 pagesThe Imci StrategyJeanette OchonNo ratings yet

- BHW Schedule MacalasDocument1 pageBHW Schedule Macalastinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Daily Dispensing Record Book Compack MedsDocument1 pageDaily Dispensing Record Book Compack Medstinea nigraNo ratings yet

- 2 Rev CHT Guidebook 102411Document90 pages2 Rev CHT Guidebook 102411Sangkula Laja50% (2)

- Women and Heart DiseaseDocument6 pagesWomen and Heart Diseasetinea nigraNo ratings yet

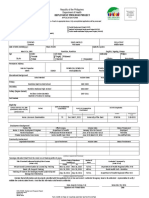

- Republic of The Phillippines: Provincial Doh Extension Office Romblon Brgy - Liwanag RPH Compound Odiongan, RomblonDocument2 pagesRepublic of The Phillippines: Provincial Doh Extension Office Romblon Brgy - Liwanag RPH Compound Odiongan, Romblontinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Specifications: What's in The BoxDocument1 pageSpecifications: What's in The Boxtinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Intravenouse Therapy Nurse: Colloid Osmotic PressureDocument2 pagesIntravenouse Therapy Nurse: Colloid Osmotic Pressuretinea nigraNo ratings yet

- ICATT Leaflet FinalDocument6 pagesICATT Leaflet Finaltinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Weight Loss TrackerDocument364 pagesWeight Loss Trackertinea nigraNo ratings yet

- MNCHN RNHealsDocument58 pagesMNCHN RNHealstinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Barangay BagacayDocument1 pageBarangay Bagacaytinea nigraNo ratings yet

- DengueDocument13 pagesDenguetinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Media 109798 enDocument13 pagesMedia 109798 entinea nigraNo ratings yet

- ICATT Presentation, Basel 22.04.2008 v1Document16 pagesICATT Presentation, Basel 22.04.2008 v1tinea nigraNo ratings yet

- Dengue FeverDocument22 pagesDengue Fevertinea nigraNo ratings yet

- DOH Nurse Deployment Project 2014 Application FormDocument1 pageDOH Nurse Deployment Project 2014 Application FormjamieboyRNNo ratings yet

- NDP Monthly Journal March 2014 RombDocument2 pagesNDP Monthly Journal March 2014 Rombtinea nigra75% (4)

- 1 292583745 Bill For Current Month 1Document2 pages1 292583745 Bill For Current Month 1Shrotriya AnamikaNo ratings yet

- FinTech BoguraDocument22 pagesFinTech BoguraMeraj TalukderNo ratings yet

- Agreement For Consulting Services Template SampleDocument6 pagesAgreement For Consulting Services Template SampleLegal ZebraNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in The Popular Sector Traditional Medicine in Sri LankaDocument10 pagesCurrent Trends in The Popular Sector Traditional Medicine in Sri Lankammarikar27No ratings yet

- How a Dwarf Archers' Cunning Saved the KingdomDocument3 pagesHow a Dwarf Archers' Cunning Saved the KingdomKamlakar DhulekarNo ratings yet

- Cristina Gallardo CV - English - WebDocument2 pagesCristina Gallardo CV - English - Webcgallardo88No ratings yet

- 4-7. FLP Enterprises v. Dela Cruz (198093) PDFDocument8 pages4-7. FLP Enterprises v. Dela Cruz (198093) PDFKath LeenNo ratings yet

- LTD NotesDocument2 pagesLTD NotesDenis Andrew T. FloresNo ratings yet

- Schneider ACB 2500 amp MVS25 N - Get Best Price from Mehta Enterprise AhmedabadDocument7 pagesSchneider ACB 2500 amp MVS25 N - Get Best Price from Mehta Enterprise AhmedabadahmedcoNo ratings yet

- NBA Live Mobile Lineup with Jeremy Lin, LeBron James, Dirk NowitzkiDocument41 pagesNBA Live Mobile Lineup with Jeremy Lin, LeBron James, Dirk NowitzkiCCMbasketNo ratings yet

- Daddy's ChairDocument29 pagesDaddy's Chairambrosial_nectarNo ratings yet

- Handout 2Document2 pagesHandout 2Manel AbdeljelilNo ratings yet

- Final Exam 2012 EntryDocument2 pagesFinal Exam 2012 EntryYonatanNo ratings yet

- Exam Notes PDFDocument17 pagesExam Notes PDFmmeiring1234No ratings yet

- Intermediate Algebra For College Students 7th Edition Blitzer Test BankDocument19 pagesIntermediate Algebra For College Students 7th Edition Blitzer Test Bankdireful.trunnionmnwf5100% (30)

- Chua v. CFI DigestDocument1 pageChua v. CFI DigestMae Ann Sarte AchaNo ratings yet

- Network Marketing - Money and Reward BrochureDocument24 pagesNetwork Marketing - Money and Reward BrochureMunkhbold ShagdarNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Fundamentals of Modern Manufacturing 6Th Edition by Groover Isbn 1119128692 9781119128694 Full Chapter PDFDocument24 pagesSolution Manual For Fundamentals of Modern Manufacturing 6Th Edition by Groover Isbn 1119128692 9781119128694 Full Chapter PDFsusan.lemke155100% (11)

- History-Complete Study NoteDocument48 pagesHistory-Complete Study NoteRahul PandeyNo ratings yet

- 0500 w16 Ms 13Document9 pages0500 w16 Ms 13Mohammed MaGdyNo ratings yet

- Ciac Revised Rules of ProcedureDocument16 pagesCiac Revised Rules of ProcedurebidanNo ratings yet

- Analyze Author's Bias and Identify Propaganda TechniquesDocument14 pagesAnalyze Author's Bias and Identify Propaganda TechniquesWinden SulioNo ratings yet

- Entrance English Test for Graduate Management StudiesDocument6 pagesEntrance English Test for Graduate Management StudiesPhương Linh TrươngNo ratings yet

- Cartagena PresentationDocument20 pagesCartagena PresentationPaula SimóNo ratings yet

- Building Security in Maturity Model: (Bsimm)Document2 pagesBuilding Security in Maturity Model: (Bsimm)cristiano.vs6661No ratings yet

- MG6863 - ENGINEERING ECONOMICS - Question BankDocument19 pagesMG6863 - ENGINEERING ECONOMICS - Question BankSRMBALAANo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. OrsalDocument17 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. OrsalKTNo ratings yet

- National Dairy Authority BrochureDocument62 pagesNational Dairy Authority BrochureRIKKA JELLEANNA SUMAGANG PALASANNo ratings yet

- Pudri RekpungDocument1 pagePudri Rekpungpz.pzzzzNo ratings yet

- European Gunnery's Impact on Artillery in 16th Century IndiaDocument9 pagesEuropean Gunnery's Impact on Artillery in 16th Century Indiaharry3196No ratings yet