Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hodina9 Strathern M The Gender of The Gift Problems With Women and Problems With Society in Melanesia - University of California Press 1988

Uploaded by

Les Yeux OuvertsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hodina9 Strathern M The Gender of The Gift Problems With Women and Problems With Society in Melanesia - University of California Press 1988

Uploaded by

Les Yeux OuvertsCopyright:

Available Formats

title: author: publisher: isbn10 | asin: print isbn13: ebook isbn13: language: subject publication date: lcc: ddc:

subject:

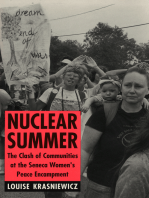

The Gender of the Gift : Problems With Women and Problems With Society in Melanesia Studies in Melanesian Anthropology ; 6 Strathern, Marilyn !ni"ersity of #alifornia Press $%&'()''%)')) $%&'(&(*'&)$) +nglish Melanesians,,Social life and customs, Women,,Melanesia,, Social conditions, -eminism, Se. role,,Melanesia *$&& G/66& S6$ *$&&eb 0'( 12'$$0 Melanesians,,Social life and customs, Women,,Melanesia,, Social conditions, -eminism, Se. role,,Melanesia co"er Page i

The Gender of the Gift page3i Page ii Studies 4n Melanesian Anthropology General Editors 5onald - Tu6in Gilbert 7 7erdt 8ena 9ederman * Michael :oung, Magicians of Manumanua: Living Myth in Kalauna ) Gilbert 7 7erdt, ed , Ritualized Homosexuality in Melanesia 0 ;ruce M <nauft, Good Company and iolence: !orcery and !ocial "ction in a Lo#land $e# Guinea !ociety

1 <enneth + 8ead, Return to the High alley: Coming %ull Circle ( =ames - Weiner, &he Heart of the 'earl !hell: &he Mythological (imension of %oi !ociety 6 Marilyn Strathern, &he Gender of the Gift: 'ro)lems #ith *omen and 'ro)lems #ith !ociety in Melanesia % =ames G #arrier and Achsah 7 #arrier, *age+ &rade+ and Exchange in Melanesia: " Manus !ociety in the Modern !tate & #hristopher 7ealey, Maring Hunters and &raders: 'roduction and Exchange in the 'apua $e# Guinea Highlands $ A 9 +pstein, ,n the Midst of Life: "ffect and ,deation in the *orld of the &olai *' =ames G #arrier, ed , History and &radition in Melanesian "nthropology ** <aren = ;rison, -ust &al.: Gossip+ Meetings+ and 'o#er in a 'apua $e# Guinea illage *) Terence + 7ays, ed , Ethnographic 'resents: 'ioneering "nthropologists in the 'apua $e# Guinea Highlands *0 Michele Stephen, "/aisa/s Gifts: " !tudy of Magic and the !elf page3ii Page iii

The Gender of the Gift Problems >ith Women and Problems >ith Society in Melanesia Marilyn Strathern !/4?+8S4T: @- #A94-@8/4A P8+SS ;erAeley B 9os Angeles B 9ondon page3iii Page i" !ni"ersity of #alifornia Press ;erAeley and 9os Angeles, #alifornia !ni"ersity of #alifornia Press, 9td 9ondon, +ngland #opyright C *$&& by The 8egents of the !ni"ersity of #alifornia -irst PaperbacA Printing *$$' 9ibrary of #ongress #ataloging in Publication 5ata Strathern, Marilyn The gender of the gift 2 Marilyn Strathern p cm DStudies in Melanesian anthropologyE ;ibliography : p 4ncludes inde. 4S;/ '()''%)')) DalA paperE * MelanesiansSocial life and customs ) WomenMelanesia Social conditions 0 -eminism 4 Title 44 Series 5!1$' S%$ *$&& 0'( 1F'$$0 &&*1)6%

Printed in the !nited States of America )01(6%&$ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum reGuirements of American /ational Standard for 4nformation SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed 9ibrary Materials, A/S4 H0$ 1&*$&1 page3i" Page "

%or 01 H1 M1+ H1 &1 and "1 L1 page3" Page "i Woman is a social being, created >ithin and by a specific society As societies differ, so too do >omen 4t is easy to forget this and to see F>omanF as a timeless, changeless category Woman in ancient Greece is seen to be the same as >oman today; only their circumstances differ -rom this "ie> emerges an ahistorical sense of the meaning of being a >oman, and of the simple continuity of our oppression An anti,>oman Guotation from Ienophon sits comfortably beside one from St Augustine, and both chime in >ith those of 8ousseau, 7egel and /orman Mailer Woman, man and misogyny become constants, despite the >orld around them turning upside do>n 4 >ould argue instead that >omen and men and the nature of misogyny and oppression are all Gualitati"ely different in different times and places The sense of similarity, of easily dra>n parallels, is illusory Women themsel"es change 4t is precisely the differences in circumstances that is crucial to the meaning and sense of becoming a >oman We must therefore understand the particularity of our o>n circumstances in order to understand oursel"es =ill =ulius Matthe>s Good and Mad *omen *$&1 The unit of in"estigation is the social life of some particular region of the earth during a certain period of time A 8 8adcliffe,;ro>n !tructure and %unction in 'rimitive !ociety *$() The future of Western society lies in its ability to create social forms that >ill maAe e.plicit distinctions bet>een classes and segments of society, so that these distinctions do not come of themsel"es as implicit racism, discrimination, corruption, crises, riots, necessary FcheatingF and FfinanglingF and so on The future of anthropology lies in its ability to e.orcise FdifferenceF and maAe it conscious and e.plicit 8oy Wagner &he ,nvention of Culture *$%( page3"i Page "ii

#@/T+/TS Preface AcAno>ledgments i. .iii

4ntroduction * Anthropological Strategies ) A Place in the -eminist 5ebate Part @ne 0 Groups: Se.ual Antagonism in the /e> Guinea 7ighlands 1 5omains: Male and -emale Models ( Po>er: #laims and #ounterclaims 6 WorA: +.ploitation at 4ssue Part T>o % Some 5efinitions & 8elations >hich Separate page3"ii Page "iii $ -orms >hich Propagate *' #ause and +ffect #onclusion ** 5omination *) #omparison /otes ;ibliography Author 4nde. SubJect 4nde. page3"iii Page i. 0'$ 01' 01( 0&( 1'$ 1*0 ))( )6& *%* *$* 10 66 $& *00 0 ))

P8+-A#+ 4t >as an early hope that feminist,inspired scholarship >ithin anthropology >ould change not Just >ays of >riting about >omen or about >omen and men but >ould change >ays of >riting about culture and society That hope has been reali6ed to some e.tent through e.perimentation >ith narrati"e modes The present e.ercise is an e.periment that e.ploits orthodo. anthropological analysis as itself a literary form of sorts 4ts style is argumentati"e Although part of the impetus for this e.ercise comes from outside anthropology, there is also an internal necessity to it: 4 am concerned >ith an area of the >orld, the islands of Melanesia, >here genderK symbolism plays a maJor part in peopleFs conceptuali6ations of social life -e> ethnographers can a"oid the issues of gender relations -e> to date ha"e thought it necessary to de"elop anything one might call a theory of gender ;y FgenderF 4 mean those categori6ations of persons, artifacts, e"ents, seGuences, and so on >hich dra> upon se.ual imageryupon the >ays in >hich the distincti"eness of male and female characteristics

maAe concrete peopleFs ideas about the nature of social relationships TaAen simply to be FaboutF men and >omen, such categori6ations ha"e K 4n this >orA, FgenderF as an unGualified noun refers to a type of category differentiation 4 do not mean gender identity unless 4 say so Whether or not the se.ing of a personFs body or psyche is regarded as innate, the apprehension of difference bet>een Fthe se.esF in"ariably taAes a categorical form, and it is this to >hich gender refers The forms FmaleF and FfemaleF indicate gender constructs in this account page3i. Page . often appeared tautologous 4ndeed, their in"enti"e possibilities cannot be appreciated until attention is paid to the >ay in >hich relationships are construed through them !nderstanding ho> Melanesians present gender relations to themsel"es is not to be separated from understanding ho> they so present sociality To taAe gender as a theoretically distinct subJect, then, >ill reGuire one to address the principles upon >hich such categori6ations are based and to asA about their generality across the societies of this region /o such attempt could ignore the origin of this interest in issues raised by Western feminist scholarship Part * of this booA tacAs bacA and forth bet>een certain anthropological and certain feminist,deri"ed Guestions pertinent to the >riting of Melanesian ethnographies o"er the last t>o decades My initial intention >as to document the influence that feminist theory might ha"e had on the anthropology of the region: >hether there >ere ne> facts and themes originating from the ne> feminism that emerged in Western +urope and /orth America o"er the later *$6's and early *$%'s, also a period of e.panding anthropological field>orA in Melanesia 4n the end, 4 did not accomplish that historical accounting 4t seems that it is easier to taAe on board ne> ideas as a matter for discussion and debate than to adopt them as precepts for ethnographic practice +arly e.ceptions include the >orA of Annette Weiner and 5aryl -eil @n the >hole, ho>e"er, the flood of general discussion on the Fanthropology of >omenF or on Fgender relationsF has not been matched by feminist, informed descriptions of entire societies +"en >here there ha"e been apparent shifts, the connections may be left to inference -e> Melanesian ethnographers refer directly to their >orA as feminist; some admit it as a conte.t for their anthropology, >hile others on >hom 4 dra> >ould esche> the label 4t may >ell be that my intention >as premature, for in the mid,*$&'s >e are in the midst of a burgeoning Fsecond >a"eF of Melanesian studies, including recently published monographs by ;renda #lay, 5eborah Ge>ert6, 9isette =osephides, Miriam <ahn, 8ena 9ederman, /ancy Munn, and 9orraine Se.ton, to mention only >omen anthropologists and only some of them 7o>e"er, e"en the limited range of earlier material that 4 did scrutini6e raised Gueries as eGually against feminist as against anthropological assumptions :et these >ere not to be conflated The one mode >as not simply to be subsumed under the other, hence the alternations Part ) is a synthesis of sorts 4t describes certain techniGues or page3. Page .i strategies in the conceptuali6ation of social relations that appear common to a range of Melanesian cultures, both those of a FpatrilinealF and of a FmatrilinealF cast The synthesis is necessarily a product of the alternations tra"ersed in Part * And these techniGues necessarily embody and are thus our e"idence for the principles to >hich 4 referred :et, really, one should dismantle this conflation in turn and grasp the cultures at staAe by a further alternation: bet>een elucidating the manner in >hich these techniGues seem to >orA for the actors in"ol"ed and the only >ay in >hich the anthropologist can maAe them >orA for him or herby laying them out as though they embodied principles of organi6ation These are in fact Guite different Ainds of productions Anthropological analysis achie"es its pro.imity to and replication of its subJectsF comprehensions through a form of comprehension, of Ano>ledge, that belongs distincti"ely to itself The opening t>o chapters, >hich introduce issues in the relationship bet>een anthropological and feminist approaches, can also be read as an ethnography of Western Ano>ledge practices 4f the body of the booA is an e.position of >hat 4 thinA of instead as Melanesian Ano>ledge practices, the conclusions reconsider strictly feminist Dmale dominationE and anthropological Dcross,cultural comparisonE Guestions in its light

The concept of Fthe giftF has long been one of anthropologyFs entry points into the study of Melanesian societies and cultures 4ndeed, it pro"ides a springboard for general theori6ing: the reciprocities and debts created by the e.change of gifts are seen to comprise a form of sociality and a mode of societal integration 4n Melanesia, gift e.changes regularly accompany the celebration of life,cycle e"ents and are, most notably, instruments of political competition @ften gifts subsume persons themsel"es, especially under patrilineal regimes >here >omen mo"e in marriage from one set of men to another, although this is not the only conte.t in >hich obJects, as they pass from donor to recipient, appear to be categori6ed as male or female 7o>e"er, one cannot read such gender ascriptions off in ad"ance, not e"en >hen >omen appear to be the "ery items >hich are gifted 4t does not follo> that F>omenF only carry >ith them a FfemaleF identity The basis for classification does not inhere in the obJects themsel"es but in ho> they are transacted and to >hat ends The action is the gendered acti"ity This is no Guibble 4n the con"entional anthropological "ie>, gift e.change is taAen as a self,e"ident act, a transaction that happens to deploy items of "arious Ainds, including male or female ones, as assets or page3.i Page .ii resources at the transactorFs disposal The beha"ior is assumed to be categorically neutral >ith po>er residing in the control of the e"ent and of the assets, as in the manner in >hich FmenF control F>omenF ;ut in Melanesian culture, such beha"ior is not construed as gender neutral: it itself is gendered, and menFs and >omenFs ability to transact >ith this or that item stems from the po>er this gendering gi"es some persons at the e.pense of others, as does the necessity and burden of carrying through transactions To asA about the gender of the gift, then, is to asA about the situation of gift e.change in relation to the form that domination taAes in these societies 4t is also to asA about the FgenderF of analytical concepts, the >orlds that particular assumptions sustain +.ploring the manner in >hich gender imagery structures concepts and relations is among feminismFs proJects; ho>e"er, my assessment of e.plicit feminist >riting remains focused on one or t>o of the debates that ha"e defined the self,described Ffeminist anthropologyF of the last decade Many of the concepts and assumptions that inform these debates prompt self,inGuiry :et the feminist mo"ement has roots so clearly in Western society that it is also imperati"e to conte.tuali6e its o>n presuppositions The moti"e is a proper one, since feminist thought itself seeAs to dislodge assumptions and preJudgments 4 taAe this endea"or seriously, through Guestioning the premises of its assault on anthropological ones At the same time, 4 ha"e >anted to document >ays in >hich anthropology might respond to feminist debate, in anthropologyFs conte.t This reGuires reference bacA to the social and cultural data D"i6 ethnographyE through >hich anthropology creates itself @nly thus can one taAe anthropology as seriously as feminism and not simply picA at >hat tidbits taAe oneFs polemical or theoretical fancy 4t is also important that there remain more data than my particular interests address, in order to preser"e a sense of a partial Job +thnographies are the analytical constructions of scholars; the peoples they study are not 4t is part of the anthropological e.ercise to acAno>ledge ho> much larger is their creati"ity than any particular analysis can encompass ;y the same toAen, although it is necessary to present arguments through an historically and geographically specific range of material, and the cultures and societies of Melanesia pro"ide this range, this booA is not only about Melanesia 4t is also about the Ainds of claims to comprehension that anthropology can and cannot maAe page3.ii Page .iii

A#</@W9+5GM+/TS The cause and origin of this booA ha"e separate sources 4ts cause >as an in"itation from the 5epartment of Anthropology in the !ni"ersity of #alifornia at ;erAeley to gi"e a series of general lectures in *$&1 4ts origin belongs to The Australian /ational !ni"ersity in #anberra, >here 4 spent *$&0*$&1 as a member of a 8esearch Group in the 5epartment of Anthropology The Group addressed itself to FFGender 8elations in the South>estern Pacific: 4deology, Politics, and Production,L and 4 borro>ed this title for my lectures

4 o>e special thanAs to the then chair of the 5epartment at ;erAeley, /elson Graburn, and to +li6abeth #olson, >hose last teaching year it >as, for maAing me so >elcome 4 also o>e much to the interest of a class of students >ho made sure 4 did not get a>ay >ith too many liberties=eanne ;ergman, /icole #onstable, 8oger 9ancaster, /ancy 9ut6, <amala ?is>es>aran Gayle 8ubin and Marilyn Gelber both made substantial comments Gail <ligman, Amal 8assam, and <irim /arayan >ill Ano> >hy 4 might >ish to remember them here, as >ill Paul 8abino> The #alifornian stimulus has since been sustained through the e.tensi"e and critical appraisal that this >orA recei"ed from the editors of the Melanesian Studies series 4 ha"e been fortunate in continuing to be pro"oAed by student interest, including those students of the 5epartment of Social Anthropology in Manchester on >hom 4 ha6arded my ideas in *$&6*$&% #olleagues in the 5epartment ha"e all, intellectu, page3.iii Page .i" ally and other>ise, assisted in this enterprise, and 4 do thanA them 7o>e"er, it >as during the inter"ening year at Trinity #ollege in #ambridge that the first draft >as >ritten, and the interlude >as in"aluable The A / ! 8esearch Group >as con"ened by 8oger <eesing, Marie 8eay, and Michael :oung +lse>here 4 ha"e Joined >ith members of the group in publication: here 4 acAno>ledge my debt to their support 4 am grateful to =ames Weiner for his apt criticism of an earlier draft, to 5a"id Schneider and 9isette =osephides for their comments, and to Margaret =olly for furnishing me >ith both material and ideas #hristina Toren >ill recogni6e, 4 hope, the effect of her ad"ice With unstinting generosity the 7ead and staff of the 5epartment of Anthropology at A / ! assisted >ith the preparation of this manuscript some time after 4 had left their company: my thanAs here are a "ery inadeGuate return, as they are to the sAill and help of =ean Ashton in Manchester The ;erAeley lectures >ere an occasion for bringing together topics treated in other conte.ts They postdate but also dra> upon se"eral years of cooperation >ith Andre> Strathern 4 am, in addition, grateful to the editors and publishers of the follo>ing articles for allo>ing me to maAe use of them here: LSubJect or obJectM Women and the circulation of "aluables in 7ighlands /e> Guinea L 4n 8 7irschon, ed *omen and 'roperty+ *omen as 'roperty 9ondon: #room 7elm *$&1 L5omesticity and the denigration of >omen L 4n 5 @F;rien and S Tiffany, eds Rethin.ing *omen/s Roles: 'erspectives from the 'acific ;erAeley, 9os Angeles, 9ondon: !ni"ersity of #alifornia Press *$&1 L<no>ing po>er and being eGui"ocal L 4n 8 -ardon, ed 'o#er and Kno#ledge: "nthropological and !ociological "pproaches +dinburgh: Scottish Academic Press *$&( A special obligation must be acAno>ledged to Gilbert 7erdt The booA could not ha"e been >ritten >ithout the sharpness >ith >hich he brings into focus certain analytical approaches to the study of ritual Although it taAes the form of complementary rather than symmetrical schismogenesis, my response is to be read as positi"e rather than negati"e There is a different Aind of debt to those >hose >orA has been absorbed to become part of oneFs o>n 4n my mind, they stand as figures other than myself, but it >ould be false to thanA them separately from the use 4 maAe of their ideas hereand as ridiculous as e.pressing page3.i" Page ." gratitude for being born 4 must o>n to ha"ing cheated in one respect, ho>e"er My account represents the bibliographical limits on this e.ercise as it >as in *$&(, though 4 ha"e, of course, been influenced by >orA >hich has appeared since Without doubt, 8oy WagnerFs most recent >ritings ha"e been by far the most significant 4 ha"e not thanAed at all my other sources, >hich are the accounts of themsel"es that so many hospitalbe Melanesians ha"e gi"en to intruding anthropologists of one persuasion or another and, for myself, people from 7agen and Pangia 4t is not they >ho need this booA or >ho >ould need to >rite one liAe it ;ut if any should care to read it, 4 hope the present tense and the use of F>eF to mean F>e WesternersF >ill not pro"e too much of an irritant The problem >ith tense is that neither past nor present >ill really dothe latter suggesting timeless issues, fro6en in the ethnographic record, the former that they belong to a "anished and no longer rele"ant era /either, of course, con"eys the truth since ideas are not so mobile nor so immobile as any such

attempt to locate them suggests 4t is a pity that one is tied to the grammatical choice And it is a pity that +nglish does not ha"e a dual, for then one could also use F>eF in the sense of F>e t>oF, an inclusion that >ould not obliterate separateness 4ndeed, the >orA can be read both as an apology and an apologia for a language and a culture that does not maAe that particular possibility of central concern to the >ay it imagines itself T84/4T: #@99+G+, #AM;845G+, *$&( !/4?+8S4T: @- MA/#7+ST+8, *$&% MA849:/ ST8AT7+8 page3." Page *

4/T8@5!#T4@/ page3* Page 0

* Anthropological Strategies 4t might sound absurd for a social anthropologist to suggest he or she could imagine people ha"ing no society :et the argument of this booA is that ho>e"er useful the concept of society may be to analysis, >e are not going to Justify its use by appealing to indigenous counterparts 4ndeed, anthropologists should be the last to contemplate such a Justification Scholars trained in the Western tradition cannot really e.pect to find others sol"ing the metaphysical problems of Western thought +Gually absurd, if one thinAs about it, to imagine that those not of this tradition >ill someho> focus their philosophical energies onto issues such as Fthe relationshipF bet>een it and the indi"idual This has, nonetheless, been among the assumptions to ha"e dogged anthropological approaches to the peoples and cultures of Melanesia @ne may thinA of the Aind of attention that has been paid to their rich ceremonial and ritual life, and in some areas as rich a political life @bser"ers ha"e taAen initiation rites, for e.ample, as essentially a Fsociali6ationF process that transforms the products of nature into culturally molded creations And this process is understood from the actorFs point of "ie>: in the case of male initiation, it has been argued that men complete culturally Dthe gro>th of boys and their acGuisition of adult rolesE >hat >omen begin, and may e"en accomplish for themsel"es, naturally +Gually, it has been argued that political acti"ity is prompted by a need for cohesion, resulting in social structures of areal integration that o"ercome the refractory centrifugal inclinations of indi, page30 Page 1 "iduals Thus social control, the integration of groups, and the promotion of sociability itself ha"e all been read into peopleFs engagement in ceremonial e.change -ar from thro>ing out such frame>orAs for understanding, ho>e"er, 4 argue instead that >e should acAno>ledge the interests from >hich they come They endorse a "ie> of society that is bound up >ith the "ery impetus of anthropological study ;ut the impetus itself deri"es from Western >ays of creating the >orld We cannot e.pect to find Justification for that in the >orlds that e"eryone creates -or many purposes of study, this reflection may not be significant ;ut it must be highly significant for the >ay >e approach peopleFs creations @ne of the ethnographic interests of this booA >ill be ritual of a Aind often regarded as Guintessentially constituted through FsymbolicF beha"ior 4n the process, 4 propose that political acti"ity be apprehended in similar terms 4t becomes important that >e approach all such action through an appreciation of the culture of Western social science and its endorsement of certain interests in the description of social life That affords a "antage from >hich it >ill be possible to imagine the Ainds of interests that may be at staAe as far as Melanesians are concerned There is, moreo"er, a particular significance in Aeeping these interests separate -or much symbolic acti"ity in this region deploys gender

imagery Since the same is true of Western metaphysics, there is a double danger of maAing cultural blunders in the interpretation of male,female relations The danger stems not Just from the particular "alues that Western gender imagery puts upon this or that acti"ity but from underlying assumptions about the nature of society, and ho> that nature is made an obJect of Ano>ledge @nly by upturning those assumptions, through deliberate choice, can F>eF glimpse >hat FotherF assumptions might looA liAe The conseGuent >e2they a.is along >hich this booA is >ritten is a deliberate attempt to achie"e such a glimpse through an internal dialogue >ithin the confines of its o>n language There is nothing condescending in my intentions The #omparati"e Method /o doubt it is an e.aggeration to say that the comparati"e method has failed in Melanesia, though there is a special poignancy about the suggestion, for the region as a >hole, and especially the 7ighlands of Papua /e> Guinea, has long been regarded as an e.perimental par, page31 Page ( adise The close Ju.taposition of numerous di"erse societies, it >as thought, could register the changing effect of "ariables as a gradation of adaptations :et fe> >riters ha"e indi"idually attempted systematic comparison beyond the scope of a handful of cases /otable e.ceptions include ;ro>n D*$%&E, >ho addresses the interconnections bet>een social, cultural, and ecological systems in the 7ighlands, and 8ubel and 8osmanFs study D*$%&E of structural models of e.change relations as systemic transformations of one another Gregory D*$&)E subsumes the comparison of economic and Ainship systems under a general specification of a political economy type: each "ariant established as a member of a general class or type also "alidates the utility of the classification All three >orAs deal >ith Papua /e> Guinea The only general attempt to co"er Melanesia remains #ho>ningFs D*$%%E ethnographic o"er"ie> 4sland Melanesia, beyond Papua /e> Guinea, has been treated comparati"ely by Allen D*$&*; *$&1E through a focus on political associations and leadership 7is procedure o"erlaps >ith the more usual strategy of taAing up indi"idual themes for in"estigation, such as Ainship terminologies, male initiation, rituali6ed homose.uality, trade and e.change, and the institution of .ula e.change * #ollected essays ha"e appeared on all these topics D#ooA and @F;rien, eds *$&'; 7erdt, ed *$&)c; *$&1a; Specht and White, eds *$%&; 9each and 9each, eds *$&0E ) 7ere, stretches of ethnography are laid side by side, analytical categories being in part deri"ed from and modified by the e.amination of each case This no> freGuent practice in"ites contributions from separate authors: the collected,essay format allo>s each uniGue case to be presented through the "ision of a uniGue ethnographer 4f there is a failure in all this, it lies in the holism of the original ethnographies These comparati"e e.ercises necessarily dra> upon particular ethnographic monographs, and one reason, 4 thinA, for their paucity is faintheartedness at both the richness and the totality of these primary sources Melanesia is blessed >ith much good >orA, not a lacA of it The situation is almost liAe the one that faced 9essingFs perpetrators of &he !irian Experiments: the ends of inGuiry are already Ano>n and >hat must be found are the reasons for pursuing it 0 We ha"e considerable information about the distincti"eness of these particular cultures and societies but much less idea >hy >e acGuired it -or the holism of the monograph rests on its internal coherence, >hich creates a sense of autonomous Ano>ledge and of its o>n Justification #onseGuently, the page3( Page 6 terms >ithin >hich indi"idual monographs are >ritten >ill not necessarily pro"ide the terms for a comparati"e e.ercise 4t is of interest, in fact, that Melanesianists are currently turning to the possibilities of historical accounts, for history connects e"ents and social forms >hile simultaneously preser"ing their indi"iduality Perhaps historical understanding >ill yield a plot to fi. the relations bet>een phenomena This last phrase comes from ;eerFs D*$&0E dual in"estigation of, on the one hand, 5ar>inFs narration of the connections he percei"ed among life forms and, on the other, the contri"ance of nineteenth,century no"elists to maAe fiction, as deliberately concei"ed narrati"e, a commentary on life and gro>th She >rites of 5ar>inFs desire to specify comple.ity >ithout attempting to simplify it 7e conser"ed, in the profusion and

multi"ocality of his language, the di"ersity and multiple character of phenomena -or, as she puts it, his theory Ldeconstructs any formulation >hich interprets the natural >orld as commensurate >ith manFs understanding of itL D*$&0:*'%E The comple.ity of interrelation is another reason >hy he N5ar>inO needs the metaphoric and needs also at times to emphasise its transposed, metaphorical statusits imprecise innumerate relation and application to the phenomenological order it represents The representation is deliberately limited to that of Fcon"enienceF and does not attempt to present itself as a Just, or full, eGui"alent D*$&0:*'*E 4t is not to history that 4 myself looA, then, but to the >ay that one might hold analysis as a Aind of con"enient or controlled fiction 7o>e"er pro"isional and tentati"e anthropologists are about their findings, the systematic form that analysis other>ise taAes is its o>n enemy: We apply the con"entional orders and regularities of our science to the phenomenal >orld DFnatureFE in order to rationali6e and understand it, and in the process our science becomes more speciali6ed and irrational Simplifying nature, #e taAe on its comple.ity, and this comple.ity, appears as an internal resistance to our intention DWagner *$%(:(1, original emphasisE This is especially true >hen the phenomena are human subJects Analytical language appears to create itself as increasingly more comple. and increasingly remo"ed from the FrealitiesF of the >orlds it attempts to delineate, and not least from the languages in >hich people themsel"es describe them MaAing out ho> di"erse and comple. those >orlds are then seems to be an in"ention of the analysis, the creation of more data to gi"e it more >orA There is thus an inbuilt sense of artificiality to page36 Page % the >hole anthropological e.ercise>hich prompts the apparent solution that >hat one should be doing is aiming to simplify, to restore the clarity of direct comprehension ;ut this returns us to the "ery issue that in his narration of the de"elopment of life forms ;eer suggests 5ar>in >as trying to a"oid The organicist fiction in its nineteenth,century mode >as strong because it operated as Lboth a holistic and an analytical metaphor 4t permitted e.ploration of totalities, and of their elements, >ithout denying either, or gi"ing primacy to eitherL D;eer *$&0:*'&E There are other metaphors today on >hich the anthropologist dra>s: communicational field, ecosystem, social formation, e"en structure, all of >hich construct global conte.ts for the interconnection of e"ents and relations Their danger lies in maAing the system appear to be the subJect under scrutiny rather than the method of scrutiny The phenomena come to appear contained or encompassed by the systemics, and thus themsel"es systemic So >e get entangled in >orld systems and deep structures and >orry about the Fle"elF at >hich they e.ist in the phenomena themsel"es 7ere 4 resort to another mode by >hich to re"eal the comple.ities of social life @ne could sho> ho> they pro"oAe or elicit an analytical form that >ould not pretend to be commensurate to them but that >ould, nonetheless, indicate an analogous degree of comple.ity 4t is to this fictional end that 4 contri"e to gi"e the language of analysis an internal dialogue This is attempted in t>o >ays -irst, 4 sustain a running argument >ith >hat 4 identify as the premises on >hich much >riting on Melanesia Dthough not of course restricted to itE has been based These premises belong to a particular cultural mode of Ano>ledge and e.planation Second, 4 do not imagine, ho>e"er, 4 can e.tract myself from this mode: 4 can only maAe its >orAings "isible To this end, 4 e.ploit its o>n refle.i"e potential Thus my narrati"e >orAs through "arious relations or oppositions; to the >e2they a.is 4 add gift2commodity and anthropological2feminist "ie>points 9et me spell this out The difference bet>een Western and Melanesian D>e2theyE sociality means that one cannot simply e.tend Western feminist insights to the Melanesian case; the difference bet>een anthropological2feminist "ie>points means that the Ano>ledge anthropologists construct of Melanesia is not to be taAen for granted; the difference bet>een gift2commodity is e.panded as a metaphorical base on >hich difference itself may be apprehended and put to use for both anthropological and feminist purposes, yet remains rooted in Western metaphysics While all three are fictions, that page3%

Page & is, the oppositions >orA strictly >ithin the confines of the plot, the cultural reasons for choosing them lie beyond the e.ercise, since the e.ercise itself is no more conte.t,free than its subJect matter #omparati"e procedure, in"estigating "ariables across societies, normally de,conte.tuali6es local constructs in order to >orA >ith conte.t,bound analytic ones The study of symbolic systems presents a different problematic 4f theoretical interest becomes directed to the manner in >hich ideas, images, and "alues are locally conte.tuali6ed, de,conte.tuali6ation >ill not >orA Analytic generalities must be acGuired by other means The tasA is not to imagine one can replace e.ogenous concepts by indigenous counterparts; rather the tasA is to con"ey the comple.ity of the indigenous concepts in reference to the particular conte.t in >hich they are produced 7ence, 4 choose to sho> the conte.tuali6ed nature of indigenous constructs by e.posing the conte.tuali6ed nature of analytical ones This reGuires that the analytical constructs themsel"es be located in the society that produced them -or members of that society, of course, such a laying bare of assumptions >ill entail a laying bare of purpose or interest To taAe the third of the fictions: one possibility of acGuiring distance on anthropological constructs lies in critiGues of the Aind afforded by feminist scholarship Such critiGues incorporate clearly defined social interests, and thereby pro"ide an indirect commentary on the conte.ts of anthropologistsF ideas and on their interests These comprise both the accepted premises of social science inGuiry and the peculiar constraints of scholarly practice itself, including its literary form 4t is as a constant reminder of such Western academic interests that 4 Ju.tapose anthropological concepts >ith ideas and constructs dra>n from a domain of a scholarly discourse >ith >hich it both o"erlaps and is at odds The difference bet>een them is sustained as a fiction if only because 4 separate and obJectify distincti"ely FfeministF and distincti"ely FanthropologicalF "oices A rather limited range of material is presented on both sides ;ut that limitation is partly determined by the attempt to pro"ide some Aind of history of the >ay anthropological and feminist ideas are intert>ined, although there is nothing linear here 4n the crossings,o"er and blocAages bet>een ideas, >e shall encounter repetitions and contradictions of all sorts that emulate not only social life but also our hapha6ard methods for describing it 4n addition, their pro.imity is also sustained as a fiction >ithin the narrati"e form DFanalysisFE of this account A strong feminist tradition, especially on the page3& Page $ #ontinent De g , MarAs and de #ourtri"on *$&(E, >ould see this as sub"erting feminist >ritingFs distincti"e aims Dsee also +lshtain *$&)E 4ndeed, although many a.ioms of feminist scholarship appear to ha"e continuities >ith anthropological ones, its different aims indicate the different purposes that moti"ate inGuiry in the first place 4ts debates are not grounded in anthropological termsmaAing them at once a>A>ard and interesting Thus the significance of feminism is the relati"e autonomy of its premises as far as anthropology is concerned: each pro"ides a critical distance on the other 4deally, one >ould e.ploit the e.tent to >hich each talAs past the other 4deally one >ould do the same for the cross,cultural e.ercise, for it cannot be assumed that FtheirF conte.ts and FoursF >ill be recogni6ably eGui"alent What has to be analy6ed are precisely FtheirF conte.ts for social action This is the subJect matter of those holistic monographs >hich present such self,contained, self,referential >orlds To go beyond them is to proceed in the only >ay possible, to open up FourF o>n self,referencing strategies -or much anthropology, including that of a 8adcliffe,;ro>nian Aind, symbolic systems are intelligible >ithin conte.ts apprehended as a social order or society 8adcliffe,;ro>n himself separated FDsocialE structureFthe roles and positions that maAe up a societyfrom FcultureF, the toAens and signals by >hich its members Ano> about themsel"es Gellner suggests that 8adcliffe,;ro>nFs particular formulation allo>s one FFto asA >hat Aind of structure it is >hich does, and does not, lead to a self,conscious >orship of cultureL D*$&):*&%E @ne may asA the same Guestion of FsocietyF as a conceptuali6ed >hole 4n >hat Ainds of cultural conte.ts do peopleFs self,descriptions include a representation of themsel"es as a societyM :et the Guestion is absurd if one assumes that the obJect of study is Lall that is inscribed in the relationship of familiarity >ith the familiar en"ironment, the unGuestioning apprehension of the social >orld >hich, by definition, does not reflect on itselfL D;ourdieu *$%%:0, emphasis remo"edE 4t >ould be liAe reGuiring characters linAed by an authorFs plot to entertain the idea of that plot What becomes remarAable, then, is its taAen,for,granted status in much anthropological inGuiry into symbolic forms, the ease >ith >hich it is argued that people represent FsocietyF to themsel"es This assumption on behalf of others is, of course, an assumption on behalf of the obser"ers >ho FAno>F they belong to a society 8unciman underlines the parado. After all, it is the characteristic

page3$ Page *' of sociological e.planation Dhe arguesE that Lit reGuires the in"ocation of theoretical terms una"ailable to those to >hose beha"iour they are to be appliedL D*$&0:(0E -or instance, NtOo understand in the tertiary sense the social theory of the >riters of ancient 8ome, it is necessary to be a>are that they themsel"es >ere not a>are of the need to describe the society in >hich they li"ed from any other than >hat >e >ould no> regard as a limited and unrepresentati"e point of "ie> D*$&0:(0, original emphasisE 8unciman in"erts the accepted priorities by >hich social scientists often imply that the end of their endea"ors is e.planation After reportage and e.planation comes description This is >hat he means by understanding in the tertiary sense: con"eying as much as can be con"eyed about an e"ent to gi"e a sense of >hat it >as liAe for those in"ol"ed in it 4ndeed, in his "ie>, the distincti"e problems of social science are precisely those of description, not e.planation Good descriptions in turn ha"e to be grounded in theory, Lthat is, some underlying body of ideas >hich furnishes a reason for both readers of them and ri"al obser"ers of >hat they describe to accept themL D*$&0:))&E This is the reason >hy Lthe concepts in >hich descriptions are grounded are unliAely to be those used by the agents >hose beha"iour is being describedL D*$&0:))&E :et that Ano>ledge of unliAeliness has itself to be contri"ed in order to be con"eyed Tertiary understanding includes its o>n sense of difference from its obJects 4f my aims are the synthetic aims of an adeGuate description, my analysis must deploy deliberate fictions to that end 4 am concerned, then, not to elucidate specific local conte.ts for e"ents and beha"ior, but to elucidate a general conte.t for those conte.ts themsel"es: the distincti"e nature of Melanesian sociality TaAen for granted by Melanesians, this general conte.t can only be of interest to Foursel"esF +"idence must rest >ith the specificities, but the use of them is synthetic This being the case, the comparati"e procedure of laying out the relations bet>een different social systems cannot be an end in itself At the same time, it >ould be ob"iously self,defeating to turn aside from greater systematisation into greater ethnographic detail 8ather, 4 hope that the e.ogenous inter"ention of feminist,inspired scholarship >ill contribute to>ards an understanding of general Melanesian ideas about interaction and relationships >hich >ill be e"idently not reducible to those of Western social science These conte.ts are to be contrasted, not conflated At the least, confronting the premises of page3*' Page ** feminist scholarship should pre"ent us from apprehending those in any a.iomatic >ay All that can be offered initially is a prescription: one cure to the present impasse in the comparati"e anthropology of Melanesia might be to indulge less in our o>n representational strategiesto stop oursel"es thinAing about the >orld in certain >ays Which >ays >ill pro"e profitable >ill depend on our purpose Simply because it itself, as a metaphor for organi6ation, organi6es so much of the >ay anthropologists thinA, the idea of FsocietyF seems a good starting point /egati"ities: 8edescribing Melanesian Society This is no ne> strategy 4n recent years, 4 ha"e made an easy li"ing through setting up negati"ities, sho>ing that this or that set of concepts does not apply to the ethnographic material 4 Ano> best, from 7agen in the Western 7ighlands Pro"ince of Papua /e> Guinea @ne set centers on the unusual status 7agen enJoys "is,P,"is other 7ighlands societies 4t is among the fe> that do not define the se.es through general initiation into cults or through puberty rituals 1 4n reflecting on this absence, 4 >as led into other absences: for instance, that 7ageners do not imagine anything comparable to >hat >e >ould call the relation bet>een nature and culture This is a negati"ity of a different order The former case dra>s on a comparison >ith other Melanesian societies >here initiation ritual e.ists; the latter on a comparison >ith constructs of Western society,( for the circumstances >here the categories seem applicable ha"e to be defined by e.ogenous criteria /o> >hen 9each D*$(%:*01E remarAed of Malino>sAi that he >ould Lneed to maintain that, for the Trobrianders themsel"es, FTrobriand culture as a >holeF does not e.ist 4t is not something that can be reported on by Trobrianders, it is something that has to be disco"ered and constructed by the ethnographer,L his sarcasm >as directed at the e.tent to >hich

Malino>sAi underplayed the ideological significance of >hat the Trobrianders did say and report upon L7e appears to ha"e regarded the ideal construct of the nati"e informant as simply an amusing fiction, >hich could at best ser"e to pro"ide a fe> clues about the significance of obser"ed beha"iourL D*$(%:*0(E ;ut my intentions >ere the oppositenot to fill in the terms that indigenous conceptuali6ations lacAed but to create spaces that the e.ogenous analysis lacAed 4t is not that Melanesians ha"e no images of unities or >hole entities but that page3** Page *) >e obscure them in our analyses The hope here, then, is for something more comprehensi"e than simply demonstrating the inapplicability of this or that particular Western concept 6 4t is important to sho> that inapplicability is not Just a result of poor translation @ur o>n metaphors reflect a deeply rooted metaphysics >ith manifestations that surface in all Ainds of analyses The Guestion is ho> to displace them most effecti"ely 4 approach the artifacts and imagesthe culturesof Melanesian societies through a particular displacement We must stop thinAing that at the heart of these cultures is an antinomy bet>een FsocietyF and Fthe indi"idualF There is nothing ne> about this admonition The history of anthropology is littered >ith cautions to the effect that >e should not reify the concept of society, that the indi"idual is a cultural construct and an embodiment of social relations, and so on They deri"e, by and large, from refle.i"e scrutiny of Western categories of Ano>ledge and from radical positions on their ideological character 4ndeed, one of my intentions in introducing feminist debate is to point to a contemporary critiGue autochthonous to Western culture 7o>e"er, of all the "arious cultural propositions that one could upturn, 4 choose this displacement for three reasons -irst is the tenacity of its persistent appearance as a set of assumptions underlying a >hole range of approaches in anthropological thinAing about Melanesia Second is its usefulness as a focus for organi6ing ho> one might thinA about Melanesian ideas of sociality 4 >ish to dra> out a certain set of ideas about the nature of social life in Melanesia by pitting them against ideas presented as Western orthodo.y My account does not reGuire that the latter are orthodo. among all Western thinAers; the place they hold is as a strategic position internal to the structure of the present account -inally, it is germane that the proposition is framed as a relationship bet>een terms Society and indi"idual are an intriguing pair of terms because they in"ite us to imagine that sociality is a Guestion of collecti"ity, that it is generali6ing because collecti"e life is intrinsically plural in character FSocietyF is seen to be >hat connects indi"iduals to one another, the relationships bet>een them We thus concei"e of society as an ordering and classifying, and in this sense a unifying force that gathers persons >ho present themsel"es as other>ise irreducibly uniGue Persons recei"e the imprint of society or, in turn, may be regarded as changing and altering the character of those connections and relations ;ut as indi, page3*) Page *0 "iduals, they are imagined as conceptually distinct from the relations that bring them together While it >ill be useful to retain the concept of sociality to refer to the creating and maintaining of relationships, for conte.tuali6ing MelanesiansF "ie>s >e shall reGuire a "ocabulary that >ill allo> us to talA about sociality in the singular as >ell as the plural -ar from being regarded as uniGue entities, Melanesian persons are as di"idually % as they are indi"idually concei"ed They contain a generali6ed sociality >ithin 4ndeed, persons are freGuently constructed as the plural and composite site of the relationships that produced them The singular person can be imagined as a social microcosm This premise is particularly significant for the attention gi"en to images of relations contained >ithin the maternal body ;y contrast, the Ainds of collecti"e action that might be identified by an outside obser"er in a male cult performance or group organi6ation, in"ol"ing numbers of persons, often presents an image of unity This image is created out of internal homogeneity, a process of de,plurali6ation, manifested less as the reali6ation of generali6ed and integrati"e principles of organi6ation itself and more as the reali6ation of particular identities called into play through uniGue e"ents and indi"idual accomplishments 4t is not enough, ho>e"er, to substitute one antinomy for another, to conclude that Melanesians symboli6e collecti"e life as a unity, >hile singular persons are composite Such a distinction implies that the relation bet>een them might remain comparable to that bet>een society and indi"idual And the problem >ith that as a relationship is the Western corollary: despite the difference bet>een society and indi"idual, indeed

because of it, the one is regarded as modifying or someho> controlling the other At the heart of the antinomy is a supposed relation of domination Das in our contrasting ideas about society >orAing upon indi"iduals and indi"iduals shaping societyE Whate"er they are concerned >ith, Aey transformations of Melanesian cultures are not concerned >ith this relation While collecti"e e"ents do, indeed, bring together disparate persons, it is not to FmaAeF them into social beings @n the contrary, it may e"en be argued that such de,plurali6ed, collecti"e e"ents ha"e as much an amoral, antisocial character to them as do autonomous persons >ho go their o>n >ay & The relations at issue in"ol"e homologies and analogies rather than hierarchy 4n one sense, the plural and the singular are Fthe sameF They are homologues of one another That is, the bringing together of many page3*0 Page *1 persons is Just liAe the bringing together of one the unity of a number of persons conceptuali6ed as a group or set is achie"ed through eliminating >hat differentiates them, and this is e.actly >hat happens >hen a person is also indi"iduali6ed The causes of internal differentiation are suppressed or discarded 4ndeed, the one holistic condition may elicit the other Thus a group of men or a group of >omen >ill concei"e of their indi"idual members as replicating in singular form DFone manF, Fone >omanFE >hat they ha"e created in collecti"e form DFone menFs houseF, Fone matrilineageFE 4n other >ords, a plurality of indi"iduals as indi"iduals DFmanyFE is eGual to their unity DFoneFE $ The suppression of internal differentiation occurs, ho>e"er, in a plurali6ed conte.t of sorts This is the plurality that taAes the specific form of a differentiated pair or duo FManyF and FoneF may be homologous, but neither is to be eGuated >ith a pair When either a singular person or a collecti"e group comes into relation >ith another, that relation is sustained to the e.tent that each party is irreducibly differentiated from the other +ach is a unity >ith respect to or by analogy >ith the other The tie or alliance bet>een them cannot be subsumed under a further collecti"ity, for the dyad is a unity only by "irtue of its internal di"ision #onseGuently, paired entities cannot be brought together, as >e might be tempted to suggest, under the integrating rubric of Fa >ider societyF Single, composite persons do not reproduce Although it is only in a unitary state that one can, in fact, Join >ith another to form a pair, it is dyadically concei"ed relationships that are the source and outcome of action The products of relationsincluding the persons they createine"itably ha"e dual origins and are thus internally differentiated This internal, dualistic differentiation must in turn be eliminated to produce the unitary indi"idual Social life consists in a constant mo"ement from one state to another, from one type of sociality to another, from a unity Dmanifested collecti"ely or singlyE to that unity split or paired >ith respect to another This alternation is replicated throughout numerous cultural forms, from the manner in >hich crops are regarded as gro>ing in the soil to a dichotomy bet>een political and domestic domains Gender is a principal form through >hich the alternation is conceptuali6ed ;eing FmaleF or being FfemaleF emerges as a holistic unitary state under particular circumstances 4n the one,is,many mode, each male or female form may be regarded as containing >ithin it a suppressed composite identity; it is acti"ated as androgyny transformed 4n the dual mode, a male or page3*1 Page *( female can only encounter its opposite if it has already discarded the reasons for its o>n internal differentiation: thus a di"idual androgyne is rendered an indi"idual in relation to a counterpart indi"idual An internal duality is e.ternali6ed or elicited in the presence of a partner: >hat >as FhalfF a person becomes FoneF of a pair As there are t>o forms of plurality Dthe composite and the dualE, so there are t>o forms of the androgyne or, >e might say, t>o forms of the singular To say that the singular person is imagined as a microcosm is not simply to dra> attention, as obser"ers repeatedly do, to the e.tensi"e physical imagery in Melanesian thought that gi"es so much significance to the body 4t is to percei"e that the body is a social microcosm to the extent that it taAes a singular form This form presents an image of an entity both as a >hole and as holistic, for it contains >ithin it di"erse and plural relations The holistic body is composed in reference to these relationships, >hich are in turn dependent for their "isibility on it The t>o modes to >hich 4 ha"e

referred may thus also be described as stages in body process To be indi"iduated, plural relations are first reconceptuali6ed as dual and then the dually concei"ed entity, able to detach a part of itself, is di"ided The eliciting cause is the presence of a different other The singular person, then, regarded as a deri"ati"e of multiple identities, may be transformed into the di"idual composed of distinct male and female elements ;ut there is a difference bet>een the t>o constructions or modes 4n the first, plurality can be eliminated through difference being encompassed or eclipsed, >hile in the second case, elimination is achie"ed through detachment These operations are basic to the >ay in >hich relationships and the producti"ity of social life are "isuali6ed ;ecause gender pro"ides a form through >hich these "isions are reali6ed, it is also formed by them 4f >e must stop thinAing that at the heart of Melanesian culture is a hierarchical relation bet>een society and the indi"idual, >e must also stop thinAing that an opposition bet>een male and female must be about the control of men and >omen o"er each other 8ealising this ought to create fresh grounds for analy6ing the nature of that opposition and of interse.ual domination in these societies ;eyond /egation We do not, of course, ha"e to imagine that these ideas e.ist as a set of ground rules or a Aind of template for e"erything that Melanesians page3*( Page *6 do or say 8ather, as in the manner in >hich Westerners may thinA about the relationship bet>een indi"idual and society, they occur at moments >hen Melanesians d>ell on the reason or causes for actions They are the DculturalE form that their thoughts taAetantamount to a theory of social action As an implemented or acted upon theory, >e might eGually >ell call it a practice of social action 4ndeed, these constructs become "isible on occasions >hen people do not simply >ish to reflect on the causes of action but to create the conditions for fresh actions Actions are Ano>n by their effects and outcomes These constructs are thus also a theory and practice of production 4 return to the point that one Aind of producti"e acti"ity Dthe Western anthropological analysis found in this booAE is being used to e"oAe another Aind of producti"e acti"ity Dho> the people 4 call Melanesians conceptuali6e the causes and outcomes of actionE +"en if commensurability >ere desirable, ho>e"er close the attempt to represent the one in terms of the other, the aims of the t>o acti"ities are Guite disparate 4t is ob"iously shortsighted merely to be disparaging, to say that FourF ideas are FethnocentricF and that >e should looA at FtheirF ideas 4nstead, as 4 ha"e argued, >e need to be conscious of the form that our o>n thoughts taAe, for >e need to be conscious of our o>n interests in the matter Din this case, the interests of Western anthropologists in the analysis of other societiesE An appreciation of the interested nature of all producti"e acti"ity, academic or other>ise, is one thing The fact that our thoughts come already formed, that >e thinA through images, presents an interesting problem for literary production itself Their ideas must be made to appear through the shapes >e gi"e to our ideas +.ploiting the semantics of negation Dthe I or : ha"e Fno societyFE is to pursue the mirror,image possibility of suggesting that one type of social life is the in"erse of another This is the fiction of the us2them di"ide The intention is not an ontological statement to the effect that there e.ists a type of social life based on premises in an in"erse relation to our o>n 8ather, it is to utili6e the language that belongs to our o>n in order to create a contrast internal to it #onseGuently, the strategy of an us2them di"ide is not meant to suggest that Melanesian societies can be presented in a timeless, monolithic >ay, nor to assume some fi.ity in their state,of,being >hich renders them obJects of Ano>ledge And there is more to it than their entry into anthropological accounts as figments of the Western imagination The intention is to maAe e.plicit the practice of anthropological description itself, >hich creates its o>n conte.t in page3*6 Page *% >hich ideas dra>n from different social origins are Aept distinct by reference to those origins #reating a Aind of mirror,imagery gi"es a form to our thoughts about the differences The strategy of negation can contribute to a larger strategy To say the I do not ha"e this or that is a statement highly dependent on the character of >hat this or that is for those >ho do ha"e it 4t can thus be seen simultaneously as a displacement of meaning and as an e.tension of it 4 displace >hat F>eF thinA society is by a set of different constructs, promoted in opposition to order to suggest an analogy >ith FtheirF

"ie> At the same time, that "ery analogy grasped as a comparison, treating both sets of ideas as formulae for social action, *' then e.tends for us the original meaning of the concept The idea of FanalysisF is integral to the argument Much of the material of this booA rests on symbolic e.egesis, that is, on the elucidation of >hat an earlier anthropology >ould call peopleFs representations of themsel"es, in their "alues and e.pectations and in the significances they gi"e to artifacts and e"ents The analytical procedure thus appears to be that of a decoding type ;ut it is important to be clear >hat the obJect of the e.ercise is @ne is not follo>ing through a decoding procedure that Melanesians >ould also follo> through if they >ished to bring to the surface a total map of their construction of meanings As >e Ano>, indigenous e.egetical acti"ity consists in the creation of further symbols and images, for >hich further decoding on the obser"erFs part then becomes necessary Sperber puts it: Le.egesis is not an interpretation but rather an e.tension of the symbol and must itself be interpretedL D*$%(:01E 4ndigenous decoding, so to speaA, taAes the form of transformation or symbolic inno"ation The necessity to inno"ate is characteristic of all cultural acti"ity 4t amounts to the cultural necessity to attribute meaning to e"ery successi"e act, e"ent, and element, and to formulate that meaning in terms of already Ano>n referents or conte.ts The metaphor may be one that has been repeated millions of times before, or it may be a completely original creation, but in either case it achie"es its e.pressi"e force through the contrast that it presents and the analogy that this contrast elicits DWagner *$%):&E This can be no less true of e.ogenous decoding procedures, of the relations that anthropologists lay out and the imitations or analogies they stri"e to create Anthropological e.egesis must be taAen for >hat it is: an effort to create a >orld parallel to the percei"ed >orld in an e.pressi"e medium D>ritingE that sets do>n its o>n conditions of intelligibility The creati", page3*% Page *& ity of the >ritten language is thus both resource and limitation ;y language, 4 include here the arts of narration, the structuring of te.ts and plots, and the manner in >hich >hat is thus e.pressed al>ays arri"es in a finished or completed DholisticE state, already formed, already a composition of sorts 5ecomposing these forms can only be done through deploying different forms, other compositions As a style of narration, analysis itself is a mode some>hat underrated in the current debates on ethnographic >riting :et one might see analysis as a trope for the representation of Ano>ledge, La >ay of speaAing relati"e to the purposes of a discourseL DTyler *$&1:0)&E -ascinating literary issues lie in the manner in >hich >e do indeed decompose e"ents, acts, significations in order to interpret FmeaningsF or theori6e about the relationship bet>een "ariables 4 thus find interest in the categories of analysis that ha"e been applied to the elucidation of social systems in Melanesia, most prominently perhaps that of Fthe giftF They are all heuristics And it is in this sense that 4 taAe gift e.change as a heuristic As >ith the other t>o fictions, the po>er of gift e.change as an idea lies in the contri"ance of an internal dialogue of sorts 7ere, the dialogue belongs strictly to discourse >ithin anthropology The contrast sustained in this booA bet>een commodity systems and gift systems of e.change is taAen directly from GregoryFs D*$&)E >orA Gregory himself insists that the t>o types of e.change are found together #ertainly this is true for contemporary Melanesian societies for as long as they ha"e been studied by Westerners, and his o>n account is embedded in a study of change and the coe.istence of both forms in colonial and postcolonial Melanesia /e"ertheless, insofar as he grounds the predominance of gift e.change in a Fclan,basedF as opposed to a Fclass,basedF society, he does suggest that the character of the predominant form of e.change has distincti"e social correlates 4t is important to the >ay 4 proceed that the forms so contrasted are different in social origin, e"en though the manner in >hich they are e.pressed must belong commensurately >ithin a single DWesternE discourse Thus a culture dominated by ideas about property o>nership can only imagine the absence of such ideas in specific >ays 4n addition, it sets up its o>n internal contrasts This is especially true for the contrast bet>een commodities and gifts: the terms form a single cultural pair >ithin Western political,economy discourse, though they can be used to typify differences bet>een economies that are not party to the discourse, for e.ample non,Western economies that may beha"e according to a particular page3*&

Page *$ political,economy theory >ithout themsel"es ha"ing a political,economy theory The metaphor of the FgiftF, then, holds a particular place >ithin Western formulations, and that placement is one 4 e.ploit in delineating its relation to its implied counterpart FcommodityF 4magining that one might characteri6e a >hole economy in terms of the pre"alence of gift e.change as opposed to one dominated by commodity e.change opens up conceptual possibilities for the language that concei"es of a contrast bet>een them Thus one can manipulate recei"ed usages of terms such as FpersonsF and FthingsF or FsubJectsF and FobJectsF And thus one can contri"e an analysis >hich, to follo> TylerFs musings about discourse as trope, in being FFNnOeither fully coherent >ithin itself nor gi"en specious consistency through referential correspondence >ith a >orld e.ternal to itself, announces brief coherences and enacts momentary Fas ifF correspondences relati"e to our purposes, interests, and interpreti"e abilitiesL D*$&1:0)$E The internal dialogue is formed from the multiple >ays in >hich >e might organi6e our Ano>ledge of Melanesian societies through a single language of analysis That analysis, one might add, is of course at its o>n historical point in time When Mauss D*$(1:chap 1E >as defending his use of the term FgiftF to refer to economies based on gift e.change, he then had in mind a contrast >ith the principles of the Fso called natural economyF or FutilitarianismF The idea of FcommoditiesF allo>s us to organi6e a different range of data -or the moment, 4 merely assert the ad"antage of the contrast To talA about the gift constantly e"oAes the possibility that the description >ould looA "ery different if one >ere talAing instead about commodities -inally, then, if our cultural productions depend on inno"ation, it is no surprise that much anthropological >riting is polemical The arrangements of analytical categories are o"erthro>n ;ut displacement can only come from a pre"ious position 4t thus e.tends that pre"ious position rather than refutes it This acti"ity is the hallmarA of social science Too often >e disparage the mo"ement from one position to another as relati"ity The disparagement hides the cumulati"e achie"ement of social science, >hich is constantly to build up the conditions from >hich the >orld can be apprehended ane> ** That regenerati"e capacity constitutes the ability to e.tend meanings, to occupy different "ie>points More than mimesissocial science imitating its subJect matterit maAes a distincti"e contribution to a >orld that in so many other conte.ts dra>s on tech, page3*$ Page )' nology for its models for inno"ation The metaphoric e.pansions of technology are persuasi"ely self,referential and self,"alidating There appears to be a natural transformation of ideas into engines that >orA and thus e"ince the ideas at >orA The process images a special Aind of cumulati"e Ano>ledge: it celebrates the possibility of maAing the entire uni"erse F>orAF, that is, of pro"ing that our ideas about the uni"erse >orA Technological Ano>ledge builds up to this end, but not so the Ano>ledge accumulated through social science At staAe here are >ays to create the conditions for ne> thoughts Meyer -ortes >as fond of pointing out that the force of food taboos lay in the Ano>ledge that a person can eat only for him or herself; it is not an acti"ity someone can do for another The same is true of thinAing Thoughts e.ist only as Fne>ly thoughtF, by this or that person As Wagner obser"es: 7uman actions are additi"e, serial, and cumulati"e; each indi"idual act stands in a particular relationship to the life of the indi"idual or the group, and it also FaddsF something, in a literal or figurati"e sense, to these continuities and to the situation itself Thus e"ery act, ho>e"er habitual or repetitious, extends the culture of the actor in a certain sense D*$%):&, original emphasisE 4f this is true of human action in general, >e succumb it to an interesting di"ision of labor Western technology assumes the constant production of ne> and different things, an indi"iduating obsession Sahlins D*$%6E attributed to the culture of bourgeois society ;ut in the bourgeois "ie>, social life consists in the constant rearrangement of the same things DpersonsE 4t follo>s from this "ie> that social arrangements can ne"er >orA out in any finished sense, if only because our apprehension of them not only shifts but must be made to shift :et >hat is freshly grasped each time is the possibility of a holistic description #reating the grounds for ne> thoughts emerges as a Aind of deliberate counterproduction The necessity to concei"e each ne> understanding as at once totali6ing and incomplete is intrinsic to Western culture, as it >ould ha"e to be >ith that cultureFs e"er incomplete proJect Social science seeAs to maAe that proJect an obJect of Ano>ledge 4ts preoccupation is the totali6ing FrelationshipF bet>een the indi"idual and society, bet>een culture and nature The terms are apprehended as irreducible; the transformation of one into the other as partial 4 am a>are as 4 >rite that dichotomy belongs to a DmodernistE

phase already culturally superseded /e"ertheless, it still has po>er as a collecti"i6ing obsession page3)' Page )* defining a culture that defines itself as less than the uni"erse ;y definition, it can ne"er >orA completely The Western "ie> of Western culture, then, liAe its "ie> of social science, is that it is perpetually unfinished The autonomy of the indi"idual and the recalcitrance of nature seem to pro"e the point The e.tent to >hich >e also percei"e the scope of humanAindFs domination o"er the >orld merely pro"ides alternati"e proof, for >e regard that relationship as both open to constant modification and based on an ultimate difference, as indeed >e do that bet>een men and >omen page3)* Page ))

) A Place in the -eminist 5ebate -eminist debate lies beyond the social sciences in another sense 4ts premises are not those of an incomplete proJect, an openness to the di"ersity of social e.perience that presents itself for description 4ts openness is of a different Aind, its community of scholars differently constituted After all, the idea of an incomplete proJect suggests that completion might be possible; feminist debate is a radical one to the e.tent that it must share >ith other radicalisms the premise that completion is undesirable The aim is not an adeGuate description but the e.posing of interests that inform the acti"ity of description as such 4 e.aggerate the contrast -eminist scholarship and social science share a similar structure in that their o"ert premises are not the a.iomatic apprehensions of the >orld that inform paradigms in a natural science mode They are competiti"ely based 4t is as common to find "ie>points being held openly in relation to one another as to find one superseding another To a much lesser e.tent, ho>e"er, has feminist inGuiry an interest in the relati"ity of "ie>points -or it does not, 4 thinA, seeA for constantly fresh conceptuali6ations of social life: it seeAs for only one 4t seeAs for all the >ays in >hich it >ould maAe a difference to the >orlds >e Ano> to acAno>ledge >omenFs as >ell as menFs perspecti"es <no>ledge is thus dually concei"ed and to that e.tent mirrors perpetual conflict 4t is a distincti"e characteristic of social science that it can accommodate such a "ie> among its many positions :et at the same time, a page3)) Page )0 conflict "ie> of Ano>ledge must displace all other positions @ne cannot be a half,hearted radical The conseGuences are interesting The changing perspecti"es of social science, its promotion of multiple "ie>points, each contributing its part to the >hole, yield a sense of perspecti"e itself, at least in its modernist phase 5escriptions are framed by different perspecti"es on a subJect matter @ne mo"es from one to another 4ndeed, the subJect matter, so to speaA, may also ha"e its o>n Fperspecti"eF #reating a distance bet>een scholar and obJect of Ano>ledge thereby establishes e.actly that Aind of tertiary understanding that empathi6es >ith its subJects in a distincti"e form not a"ailable to the subJects themsel"es -eminist scholarship also appears full of perspecti"es The multiple base to its debates is created through its deliberate interdisciplinary openness and the competiti"eness bet>een its o>n internal approaches 4ndeed, the self,conscious labelling of its positions are illuminating here 9iberal, 8adical, Mar.ist, Socialist feminists talA in relation to one another @ne position e"oAes others :et the manner in >hich these multiple positions are constantly recalled has a further effect They do not come together as parts of a >hole but are held as coe"al presences >ithin discussion +ach bears its o>n pro.imity to e.perience The optical illusion of holding among oursel"es many perspecti"es all at once simultaneously achie"es a sense of no perspecti"e And thus the constitution of our discourse, the internal pluralism, in fact endorses feminismFs chief aim At staAe for feminist as opposed to other scholars is the promotion of >omenFs interests, that is, the promotion of a single perspecti"e 4n the end, the FinterestsF are not so much those internal to the construction of

Ano>ledgethe canons of an adeGuate descriptionas ones e.ternal to it They come from the social >orld of >hich >e are also part Precisely because >omenFs perspecti"e is concei"ed in resistance to or in conflict >ith menFs, feminists occupy only one of these t>o positions The creation of the other happens outside us -rom the internal standpoint of our o>n position, then, to ha"e FoneF perspecti"e means to ha"e no Fperspecti"eF @ne inhabits the >orld as one finds it 7a"ing no perspecti"e is diacritic of the postmodern epoch The >ay in >hich feminist scholarship organi6es Ano>ledge challenges the manner in >hich much social science, including anthropology, also organi6es Ano>ledge 4ne"itably, among other things, it taAes apart the concept of FsocietyFthere is no such transcendental entity in the feminist "ie> that is not the ideological artifact of a category of persons >ho are rather less than the society upon >hose behalf they claim to speaA page3)0 Page )1 @rgani6ing <no>ledge F-eminismF cannot be spoAen of as a unitary phenomenon ;ut rather than here replicate the comple.ity and range of >riting that goes under its name, 4 offer a brief comment on that comple.ity itself There is an emphatic styli6ation to our self,described differences While many feminists assume that >omen e"ery>here occupy positions comparable to one another Din one >ay or another oppressedE, in terms of their o>n scholarly practice they sustain a differentiation of positions 4f at base these are eGui"alent Done can comprehend >omenFs oppression through a 8adical position on >omenFs separateness, or through a Socialist position that gi"es eGual >eight to se.ism and capitalism in accounting for se.ual ineGuality, and so onE, then only through theoretical >orA are the "ie>s Aept differentiated The possibility of feminists differing Las to >hether there are any real theoretical differences bet>een them at allL DSayers *$&):*%*E thus lies in the con"entional or artificial character of the differentiation The positions are created as dependent upon one another Theoretical differences contribute, then, to a debate constituted and sustained by cross,reference 4n our self,representations, feminists are in constant dialogue, an interlocution that maintains internal connections 4t looAs as though there is an impossible array of positions, but the positions are openly held in relation to one another They comprise La self,referential body of thoughtL D+isenstein *$&1:.i.E Much feminist >riting is conseGuently concerned >ith maAing e.plicit one "ie>point >ith respect to others De g , ;arrett *$&'; +lshtain *$&*; Sayers *$&)E 4n the +nglish,speaAing >orld, for instance, to >hich my remarAs largely refer, Mar.ist2Socialist feminism places itself in relation to both 8adical and 9iberal feminism The strategy of separatism or the arguments of biological essentialism ha"e to be countered ;ut these other "ie>points are ne"er dispatched /o "ie>point alone is self,reproducti"e: all the positions in the debate comprise the theoretical base of any one 4n other >ords, the "ast number of internal debates Dcriticism; counter,criticism and commentary; >riters talAing about one another; a fragmentation at the le"el of the indi"idual argumentsE together create a field of sorts, a discourse -eminism lies in the debate itself 4f, in the tradition of radical criticism, feminist inGuiry e.poses assumptions about the ine"itability of pre"ailing conditions, it does so through a counterpart "ision of society that taAes a plural rather than a holistic form Thus feminist organi6ations, sensiti"e to the particular page3)1 Page )( interests of >omen, are also sensiti"e to the interests of ethnic minorities and to the ethnici6ation of attributes such as se.uality A definiti"e attribute comes to denote a political position, or a theoretical one in critiGues of society * -or the potential for all positions to be FethnicallyF concei"ed is the political2theoretical face of the aesthetics of plural style The Lmodernist aestheticL that pro"ided a perspecti"e on the >orld >as LlinAed to the conception of a uniGue self and pri"ate identityL D=ameson *$&(:**1E 4f nobody no> has a uniGue, pri"ate >orld to e.press, then it remains only for stylesattributesto speaA to one another This thro>s light on a notable debate bet>een Mar.ist2Socialist and 8adical feminism: >hether primacy should be accorded to class or to gender di"isions 4t comes, 4 thinA, from our pluralist, ethnicist "ision that is intrinsically at odds >ith the systemic, structured modelling of society upon >hich class analysis must rest ) ;arrett states that the Lideas of N8Oadical feminism are for the most part incompatible >ith, >hen not e.plicitly hostile to, those of Mar.ism and indeed one of its political proJects has been to sho> ho> >omen ha"e been betrayed by socialists and socialismL D*$&':1E She endorses <uhn and WolpeFs obser"ation, Lthat