Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Rise and Fall of the Ancient City of Tula

Uploaded by

Juan María Jáuregui NavarroOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Rise and Fall of the Ancient City of Tula

Uploaded by

Juan María Jáuregui NavarroCopyright:

Available Formats

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115 DOI 10.

1007/s10814-011-9052-3

The Archaeology of Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico

Dan M. Healan

Published online: 12 August 2011 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011

Abstract The site of Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico, is well known for its distinctive architecture and sculpture that came to light in excavations initiated some 70 years ago. Less well known is the extensive corpus of archaeological research conducted over the past several decades, revealing a city that at its height covered an area of c. 16 km2 and incorporated a remarkably diverse landscape of hills, plains, alluvial valleys, and marsh. Its dense, urban character is evident in excavations at over 22 localities that uncovered complex arrangements of residential compounds whose nondurable architecture left relatively few surface traces. Evidence of craft production includes lithic and ceramic production loci in specic sectors of the ancient city. Tula possessed a large and densely settled hinterland that apparently encompassed the surrounding region, including most of the Basin of Mexico, and its area s Potos . of direct inuence appears to have extended to the north as far as San Lu Tula is believed to have originated as the center of a regional state that consolidated various Coyotlatelco polities and probably remnants of a previous Teotihuacancontrolled settlement system. Its pre-Aztec history exhibits notable continuity in settlement, ceramics, and monumental art and architecture. The nature of the subsequent Aztec occupation supports ethnohistorical and other archaeological evidence that Tulas ruins were what the Aztecs called Tollan. Keywords Tula Tollan Toltec Cities Urbanism Archaeology Mesoamerica

Introduction To Mesoamericanists, Tula conjures up many topics that go far beyond the archaeological site itself in southern Hidalgo. Chief among these is its long-standing

D. M. Healan (&) Department of Anthropology, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70118, USA e-mail: healan@tulane.edu

123

54

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

association with Tollan, the legendary city of the Toltecs whose accounts in contactperiod sources have fascinated and puzzled generations of scholars and still provoke controversy today. No less controversial are its architectural and artistic parallels to n Itza (Fig. 1, E), which have been cited as proof of Tulas status as Tollan Chiche n Itza s conquest by Toltecs. and the veracity of ethnohistorical accounts of Chiche While it would be difcult to focus at length on Tula without considering both of these issues, I am not directly concerned with questions surrounding its identi n Itza , for which the interested reader is cation as Tollan or its relationship to Chiche urged to consult a recent collection of papers on both subjects (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007). Instead, my primary concern is with our knowledge of Tula and the surrounding region based on archaeological investigations since Acostas pioneering work in the mid-20th century. Although the archaeological evidence indicates that Tula was indeed the site the Aztecs called Tollan, I simply refer to it as Tula in light of evidence that Tollan is a larger cultural construct whose origins may go back at least as far as Teotihuacan pez Luja n and Lo pez Austin 2009; Stuart 2000). For similar reasons, I do not use (Lo Toltec as a descriptor for Tula, despite its use as a formal time period in the Basin of Mexico. Tula is located in central Mexico (Fig. 1, A), an interior plateau with a long tradition of prehispanic (Mesoamerican) cities, beginning with Teotihuacan and n. A disproportionately large number were located within ending with Tenochtitla the 8,000-km2 lacustrine basin known as the Basin of Mexico, whose long and

Fig. 1 Mesoamerica and central Mexico (inset) showing (A) Tula and other sites and localities discussed n Itza ; F, Cerro Portezuelo; in text: B, Teotihuacan; C, D, Ucareo and Pachuca obsidian sources; E, Chiche G, Cerritos; H, Carabino; I, Villa de Reyes

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

55

vibrant urban tradition has been the subject of numerous studies (e.g., Millon 1973; Sanders et al. 1979; Wolf 1976). Tula lies c. 30 km north of the basin in an area bounded on three sides by mountain ranges and dissected by streams that provide passage into neighboring regions (Fig. 2). The site is situated on the southwest corner of a broad alluvial plain that is today productive agricultural land enhanced by irrigation systems, some of which go back at least to the colonial era. Volcanism has produced numerous prominent hills, including the centrally located Cerro Xicuco, and mesas along the eastern ank. The site core occupies an elongated northsouth upland along the Tula River that has been partially dissected to form two northsouth lobes upon which are situated three large mound/plaza complexes (Fig. 3, inset). The southernmost complex constituted Tulas political and religious center during its apogee; the northernmost is a smaller complex that appears to have been the political and religious center for Tulas earliest settlement. The overall similarity in plan between the two led Matos (1974a) to suggest that the earlier mound complex had served as the prototype for the later one; he designated the two complexes Tula Chico and Tula Grande,

Fig. 2 Topographic map of the Tula region showing Tulas urban limits (black) and other sites discussed in text: A, La Loma; B, Chingu; C, Acoculco; D, El Tesoro; E, La Mesa; F, Cerro La Ahumada (Mesa Grande)

123

56

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

Fig. 3 Topographic map of Tula (source: Yadeun 1974) showing mounds greater than 1 m in height and major monumental precincts (inset). Map appears to be oriented to magnetic north, which in 1973 was c. 8.2E

respectively. The Plaza Charnay is named for the French explorer who conducted excavations there in 1880. The three complexes occupy most of the 1.1-km2 area within the protected archaeological zone, although the site itself extends far beyond.

Previous archaeological research In many respects the rst archaeological investigations at Tula were conducted by a Cubas (1873) provided the earliest the Aztecs. In the post-conquest era, Garc accounts of the site. Charnay (1887) conducted exploratory excavations in and around Tula Grande in 1880. Although no major work was conducted until 1940,

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

57

Tula was visited periodically by various scholars, including Vaillant (1938), whose test excavations provided ceramic evidence for Tulas intermediate placement with respect to Teotihuacan and the Aztecs. a e Historia Beginning in 1940, Mexicos Instituto Nacional de Antropolog (INAH), under the direction of Jorge Acosta, conducted extensive investigations at Tula over an 18-year period that focused on Tula Grande. Although Acosta never wrote a denitive site report, he published numerous detailed interim reports and several syntheses (Acosta 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, 1956a, b, 1956 1957, 1957, 1959, 1960, 1961a, b, 1964, 1974; see Diehl 1989a for a summary). During the late 1960 and 1970s, two comprehensive archaeological projects were conducted by INAH (Matos 1974b, 1976) and the University of Missouri (Diehl 1974, 1981, 1983; Healan 1989). Both projects involved mapping, surface survey, and excavation at Tula and regional survey and excavation in the surrounding area. Their major contributions include determination of Tulas overall size, elucidation of its settlement history and that of the surrounding region, and a comprehensive ceramic chronology. INAH (e.g., Abascal 1982; Cobean 1982; Mastache 1996a) and other institutions (Healan et al. 1983) have conducted numerous additional investigations at Tula and in the Tula region.

Chronology Acosta (1945, 19561957) provided the rst ceramic typology and chronology for Tula. He recognized two distinct ceramic/cultural complexes, one associated with the Aztec and the other an earlier, pre-Aztec complex he called Tula-Mazapan. odo Antiguo The latter complex contained two phases, or periods, designated Per odo Reciente, although most of the 17 ceramic types he dened for the and Per Tula-Mazapan complex were present in both phases (Acosta 1945, pp. 5556), so that each period had but two unique types. Acostas use of the term Mazapan has little to do with the pottery type of the same name and instead follows Vaillants (1941) use of the term to refer to the larger cultural complex embracing all of preAztec Tula, in much the same way that others use Toltec. The current use of Mazapa, or Mazapan, to refer not only to specic pottery and gurine types but also to larger ceramic and cultural complexes and a chronological period is an unfortunate and unending source of confusion. The current ceramic typology and chronology for Tula and the Tula region, as formulated by Cobean (1978, 1990), consists of eight ceramic complexes (Prado Tesoro) and corresponding temporal phases (Fig. 4), the last three of which pertain ) phases plus to Aztec period occupations. Two earlier (La Mesa and Chingu ceramics associated with even earlier occupations were identied in the surrounding ndez area. More recent studies (e.g., Bey 1986; Equihua 2003; Estrada 2004; Herna et al. 1999; Moncayo 1999) have introduced new types and other modications to Cobeans ceramic typology and chronology. One particularly signicant revision (Bey 1986, pp. 307314) involves splitting the Tollan phase, originally embracing all of Tulas Early Postclassic apogee, into two phases (Early Tollan and Late Tollan) based principally on the appearance and proliferation of Jara Polished

123

58

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

Fig. 4 Chronological chart of central Mexico. Portions of the Basin of Mexico and Teotihuacan chronologies are omitted

Orange (hereafter Jara) in the latter phase. In fact, Acosta had previously recognized the importance of Jara, which he called Naranja a Brochazos, as a temporal marker, odo Reciente (Acosta 1945, pp. 56). using it to dene his Per Cobeans ceramic chronology revealed that Mazapa Red on Brown, or Wavy Line Mazapa, a type commonly regarded as diagnostic of Tulas apogee, is far less prevalent at Tula than previously thought; it peaked in popularity well before its apogee. Its previously exaggerated importance at Tula is in part the result of the initial use of Mazapa by Vaillant and others to embrace a number of largely unrelated types. For example, Vaillant (1938) reported that the predominant ceramic type encountered in exploratory excavations at Tula was what he called Mazapa Laquer on Yellow, which almost certainly refers to Jara (R. Cobean, personal communication 2009) and has no direct relationship to Mazapa Red on Brown. For whatever reason, the mischaracterization of Mazapa Red on Brown as diagnostic of Tulas apogee obscures temporal relationships between Tula and the Basin of Mexico, where Mazapa refers not only to a pottery type and a larger ceramic/ cultural complex but also a time period that many assume to be contemporaneous with Tulas apogee (e.g., Smith 2007, p. 583).

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

59

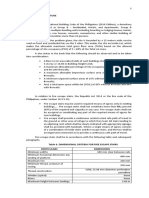

Table 1 Radiocarbon dates for samples recovered from various excavation localities at Tula and other sites in the region discussed in text Lab/no. a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w UAZ/5399 UAZ/5038 UAZ/5396 UAZ/5040 UAZ/5398 UAZ/5039 UAZ/5856 UAZ/5855 UAZ/5852 UAZ/5853 INAH/1989 INAH/1990 QL/132 QL/1020 QL/1021 QL/130 INAH/1773 UAZ/5402 UAZ/5401 UAZ/5404 UAZ/5405 INAH/317 INAH/1174 bp 1490 1300 1320 1250 1040 1490 1260 1245 1265 1240 1164 1092 1130 1110 1070 1020 1021 1530 1040 1050 830 739 710 Sigma 50 100 70 50 60 50 130 55 30 35 25 16 70 40 70 50 54 60 70 55 50 32 30 Site La Mesa La Mesa La Mesa La Mesa La Mesa Tula Chico Tula Chico Tula Chico Tula Chico Tula Chico Tula Grande Tula Grande Canal Canal Canal Canal Vivero Tepetitlan Tepetitlan Tepetitlan Tepetitlan Vivero Vivero Source Healan and Cobean (2009, g. 21) Healan and Cobean (2009, g. 21) Healan and Cobean (2009, g. 21) Healan and Cobean (2009, g. 21) Healan and Cobean (2009, g. 21) Mastache et al. (2009, g. 316) Mastache et al. (2009, g. 316) Mastache et al. (2009, g. 316) Mastache et al. (2009, g. 316) Mastache et al. (2009, g. 316) Sterpone (2006a, tabla 5) Sterpone (20002001, p. 50) Diehl (1981, p. 281) Diehl (1981, p. 281) Diehl (1981, p. 281) Diehl (1981, p. 281) ndez (1994, p. 54) Ferna Cobean and Mastache (1999, p. 72) Cobean and Mastache (1999, p. 72) Cobean and Mastache (1999, p. 72) Cobean and Mastache (1999, p. 72) ndez (1994, p. 54) Ferna ndez (1994, p. 54) Ferna

There are 23 published radiocarbon dates with adequately documented contextual information for the Tula region (Table 1, Fig. 5), a relatively small number considering the nearly 900-year span of prehispanic occupation. This does not include some additional 24 dates (Paredes 2005, g. 3) from several gico Tula (Abascal Mac as 1982), localities excavated by the Proyecto Arqueolo although little contextual or other information is currently available for these samples.

The monumental center: Tula Grande Until recently, virtually all that was known archaeologically about Tula came from Acostas investigations at Tula Grande that recovered a wealth of sculpture and monumental architecture that for better or worse came to embody the entire city. Indeed, for various reasons Tula Grande is the only part of the ancient city of which most modern visitors to the site are aware.

123

60

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

Fig. 5 Two-sigma ranges of calibrated radiocarbon dates for samples recovered from various excavation localities at Tula and other sites in the region discussed in text (full information on each sample is listed in Table 1). Calibration was performed using CALIB5.1 software (Stuiver and Reimer 1993)

Architectural characteristics Tula Grandes main plaza measures c. 130 m 9 150 m and is anked by various monumental constructions (Fig. 6). Although there are numerous large pyramidal structures in the area surrounding Tula Grande (Fig. 3), there are few such structures within Tula Grande itself, but these include the two largest pyramids at the site. Designated Pyramids B and C, their placement and orientation are reminiscent of the Sun and Moon Pyramids at Teotihuacan; Pyramid C, at least 10 m high, is similar in form to the Sun Pyramid, including an abutting platform (cuerpo adosado) supporting its stairway. The only other temple/pyramid at Tula Grande is Building K on the south side of the main plaza, where ongoing excavations (Getino 2000; Mastache et al. 2002, pp. 113114) encountered portions of its superstructure containing a single colonnade anking an elongated columned gallery (Fig. 6). Although excavation encountered a stairway on the south side of Building K, subsequent investigations have revealed that this is part of a later Aztec structure and that the original stairway, of which only traces remain, was on the north (plaza) side (R. Cobean, personal communication 2009). Remains of a similar structure, designated Building J, were encountered atop a low platform immediately to the east that was likewise heavily damaged. A common architectural form at Tula Grande consists of a large building containing two or more prominent columned halls, each with a centrally located unroofed and often sunken patio or atrium (Fig. 6, Buildings 1, 3, and 4). The largest is Building 3, the so-called Palacio Quemado, which contains three contiguous columned halls lined with benches decorated with painted friezes. Each hall is unconnected to the others and enjoys its own access to the outside. Building 1, the partially excavated Palace of Quetzalcoatl, contains at least two columned halls anked by smaller rooms. Only a small portion of Building 4 was excavated by

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

61

Fig. 6 Plan of Tula Grande monumental precinct

Acosta, who nonetheless also interpreted it as a palace based on its size and grand (9 m wide) entranceway. Subsequent excavations (Mastache et al. 2009, pp. 301304) have exposed over half of Building 4, which measures c. 45 m northsouth and 60 m eastwest and contains two columned halls and smaller anking rooms. Some scholars have challenged Acostas interpretation of Buildings 1, 3, and 4 as palaces, chiey because the combination of large central halls and small peripheral rooms and their lack of interconnectivity make them poorly designed for residential life. The spacious columned halls suggest more public activities, likewise suggested by reliefs along benches in Buildings 3 and 4 that depict processions involving

123

62

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

numerous individuals. An unusual cache of c. 200 vessels grouped by type was encountered beneath a fallen roof at the east end of the vestibule on the north side (Acosta 1945, pp. 3437). These included serving vessels and braziers, censers, and tobacco pipes, suggesting activities involving groups of people. More recently, excavation beneath the oor of Building 3 encountered an elaborate offering containing marine fauna, a pyrite mirror, and a garment made of hundreds of nely carved shell plaques (Cobean and Mastache 2003; Mastache et al. 2009, g. 18). While Mastache and Cobean suggest that the plan of the excavated portion of Building 4 resembles that of Aztec palaces (Mastache et al. 2009, pp. 303304), a closer Aztec analog, as noted by Molina (1987), is the Temple of the Eagles at n. Both are located on the east side of an L-shaped colonnaded vestibule Tenochtitla and contain porticos with an altar along the interior wall at the main entrance anked by benches with procession scenes carved in relief; each contains at least one columned hall. Klein (1987, p. 307) suggests that the Temple of the Eagles was the scene of autosacrice and other activities associated with warfare. Two broken ollas encountered on the oor of a small room in Building 4 may have been associated with group activity. There is, therefore, no compelling evidence that any of the structures inside Tula Grande were residential in function. Rather, palaces and other elite residences may have been located elsewhere, perhaps in the surrounding Monumental Precinct, as noted below. Remains of c. 375 columns appear in various congurations at Tula Grande, including colonnades. Most columns were square and constructed of stone masonry, m. XV; Getino 2000, g. 3.24), leaving often with a timber core (Acosta 1960, la few intact remains other than a base or scar in the oor where they once stood. In fact, all of the extant masonry columns at Tula Grande were reconstructed in full by Acosta (1961a, p. 43) who intentionally gave them, in his own words, un aspecto ruinoso para no desentonar con el resto del edicio. Acostas artistic license in this regard has been rightly criticized by Molina (1982), who asserts that Acosta deliberately created them to enhance the resemblance between Tula and n Itza . However, Acosta provides abundant documentation, including Chiche m. XV), that his reconstructed photographic evidence (Acosta 1945, g. 18, 1960, la columns were erected where prehispanic columns had once stood and are an accurate reection of their size, shape, and mode of construction (Healan 2001). Tula Grandes columns include monolithic anthropomorphic and zoomorphic forms, including the so-called Atlanteans, warrior columns, and serpent columns atop Pyramid B. These were encountered disarticulated in the ruins of the pyramid, and their present location atop Pyramid B reects Acostas belief that they had been columns for its superstructure. The colossal (4.6 m) Atlanteans are among the best-known prehispanic sculptures in Mesoamerica, but parts of at least four other Atlanteans also have been found at Tula (de la Fuente et al. 1988, gs. 2023), including one illustrated by Charnay (1887, p. 94). Their original provenience is unknown, although Acosta (1944, p. 146) suggests they may have been atop Pyramid C. Tulas monumental construction utilized a variety of building materials, and in distinctive ways. A signature element is the use of small-stone veneer, or tabular pieces of stone laid in courses, mortared with lime or mud, and often covered with

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

63

lime plaster. Small-stone veneer was commonly applied to benches, columns, altars, and even whole pyramids (e.g., Acosta 1974, gs. 24). It also is encountered in domestic architecture, often on structures interpreted as domestic altars, for which an interesting variant involved courses of pottery sherds instead of tabular stone (e.g., Healan 1989, g. 12.17). Substructure platforms were constructed of ll enclosed by stone masonry, a common technique in Mesoamerica, but in some cases the ll involved courses of boulders, cobbles, and soil rather than unconsolidated rubble. Walls were commonly constructed of stone cobbles laid in courses, but at least Buildings 3 and 4 contain adobe-block walls. Adobe-block construction is also quite common in Tulas domestic architecture, but its use in monumental construction is more elaborate, involving walls up to a meter thick faced with mud or lime plaster, paint, smallstone veneer, or some combination of these. Particularly surprising is the widespread use of mud rather than lime as mortar in walls of stone construction, despite the abundance of lime and its widespread use as a decorative plaster. Tula Grandes use of mud-mortared stone or adobe-block walls covered with decorative facades prompted Covarrubiass (1957, p. 273) oft-cited dictum that these buildings were meant to impress, but not to last. The preference for adobe blocks and mud mortar at Tula Grande may be less a reection of hucksterism than an architectural tradition whose roots may be embedded in the cultural milieu of Tula Grandes builders. At the same time, Covarrubias is accurate in his assessment of the poor long-term durability of Tulas architecture. Compared to Teotihuacan, where structures constructed of stone and concrete have left ubiquitous, easily discernible surface remains, very few of Tulas structures, particularly domestic structures, are directly visible today. However, even adobe cities such as Tula leave surface traces, although a variety of methods are required to discern them. Probable skull rack During exploration of Ballcourt 2 in the 1960s, remains of a rectangular platform and an adjacent smaller one were encountered immediately to the east and appear to be a skull rack, or tzompantli, to judge from the numerous fragments of human teeth and crania that were found on top. Beyond what is mentioned in the ofcial INAH guidebook and in printed information at the archaeological zone, there is little published information about the structure other than a brief description (Matos 1972, p. 115). The extant platform is unreconstructed beyond consolidation of its outer wall, a single talud or sloping body faced with small-stone veneer with traces of lime plaster. Inside the platform Matos encountered what he described as an offering box containing a large blade or knife (my translations), terms that until recently usually referred to bifaces rather than prismatic or percussion blades. According to Matos, associated ceramics suggest the structure is Aztec, but the use of small-stone veneer, while highly characteristic of Tulas monumental construction, is not a feature of Aztec construction at Tula. As described below, numerous Aztec offerings have been encountered in the ruins of Tula Grande, including bifaces inside stone boxes or other containers. More precise dating of this structure

123

64

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

is important in order to determine whether the famous tzompantli at Tenochtitlan was copied from Tula, or vice versa. Monumental art Acosta recovered numerous sculptures that exhibit a corpus of distinctive artistic and stylistic traits often labeled Toltec, which I describe here only briey; there are two encyclopedic treatments of Tulas sculpture (de la Fuente et al. 1988; nez Garcia 1998) and several studies of more specic aspects (Kristan-Graham Jime 1989, 1993, 2007; Mastache et al. 2002). Tulas sculpture generally is made of volcanic rock, presumably of local manufacture, given at least one rural site with evidence of such (Mastache et al. 2002, g. 10.7). Some is free-standing, in-theround sculpture, including the colossal Atlanteans and serpent columns atop Pyramid B and the equally well-known chacmools, or reclining human gures. Most of Tulas sculpture, however, is bas relief, made on panels of soft volcanic rock that is easily carved and, unfortunately, easily weathered. Tulas monumental art stresses repetition, including the numerous reclininggure bas relief panels depicting elaborately attired humans in a supine pose typically clutching staffs or weapons (Mastache et al. 2009, g. 14). A large number of panels were recovered from the columned halls in Building 3, at least 20 from one hall alone, where they appear to have lined the open ceilings of the interior patios. The most dramatic forms of repetitive art include (1) painted reliefs in and around Building 3 depicting processions of elaborately attired individuals with paraphernalia that suggest merchants, rulers, or warriors (Kristan-Graham 1993; Mastache et al. 2009, pp. 300, 303); (2) processions of canines, felines, and raptoral birds along Pyramid B; and (3) processions of serpents engorging or disgorging human skeletons along the coatepantli, or serpent wall. Aside from the painted friezes, we have little other evidence of painting or murals at Tula Grande, although this is to some extent a result of poor preservation. Many of the mud or lime-plaster wall coatings retained traces of paint, including broad horizontal bands of red, yellow, and black in Building 3; portions of a mural depicting a procession of at least two individuals was encountered in Building 1 m. XVIa, XVIb). (Acosta 1964, la Acostas explorations documented a remarkably high degree of similarity in the n Itza . The use of columns in colonnades, art and architecture of Tula and Chiche atop pyramids, and inside columned halls and galleries and the use of benches constitute the most salient similarities between the two sites. Similarities in sculpture involve not only the same media and modes of human and animal representation but also highly specic details of costume and accoutrements. The nature of these similarities and who had them rst have been subject to debate among Mesoamerican archaeologists and art historians for more than a century. The debate has grown more complex with the discovery of colonnades, columned halls, and skull racks at sites in northern Mexico (Hers 1989; Kelley 1978; Nelson 1997) n Itza (Aveni et al. 1982). that may be older than those at either Tula or Chiche Although the Tula Grande mound/plaza complex is perhaps the most prominent feature, it is but one component of a larger zone of mounds and plazas that form a

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

65

larger monumental precinct covering most of the surrounding hilltop (Fig. 3). Excavations of three large mounds in this area (Fig. 7, a, b, k) encountered large, well-constructed buildings that appear to have been residential (Acosta 1944, p. 156; Charnay 1887), suggesting that palaces and other residences of Tulas ruling class were situated in the surrounding area.

Fig. 7 Planimetric map of Tula (source: Stoutamire 1975) showing urban limits as dened by Mastache et al. (2002) and excavation localities discussed in text: a, Toltec Palace (Charnay 1887); b, Building 2 guez 1976); d, Museo Acosta (Paredes 1992); e, Corral (Healan a and Rodr (Acosta 1944); c, Daini (Pen ndez 1994); g, Canal (Healan 1989); h, Cruz (Healan et al. 1982); i, El Corral 1989); f, Vivero (Ferna culo 1 (Paredes (Acosta 1974); j, La Nopalera (Paredes 1990); k, Toltec House (Charnay 1887); l, Mont ndez Reyes et al. 1999); o, Colonia Pemex 1990); m, U27-28 (Mastache et al. 2002); n, U98 (Herna (Matos 1976); p, Viaducto (Paredes 1990); q, Zapata II (Paredes 1990); r, Pozo 16 (Paredes 1990); s, Mormon Church (Mastache et al. 2002); t, Canadia School (Mastache et al. 2002); u, Zona Urbana Norte (Getino n.d.); v, Unnamed (Excelsior 1 December 2009)

123

66

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

Beyond Tula Grande: The Tollan phase city Since Acostas pioneering work at Tula Grande, three separate investigations (Healan and Stoutamire 1989; Mastache and Crespo 1982; Yadeun 1974, 1975) have focused on the larger city, including determination of its overall size. Although utilizing different approaches (Healan 2009a, pp. 6970), these investigations reveal that at its height Tula covered an area of about 16 km2, with a maximum north south length of c. 6 km and a maximum width of c. 4 km, encompassing a remarkably diverse landscape of hills, plains, alluvial valleys, and even brackish marsh (Figs. 3 and 7). INAHs photogrammetric mapping project (Yadeun 1974, 1975) identied over 1,000 mounds a meter or more in height whose distribution forms distinct clusters of varying size and density (Fig. 3). While a direct correlation between mound and occupation density might be assumed, this does not appear to be the case given that some of the highest densities of Tollan complex pottery from the Missouri project survey occur in areas where few mounds were identied. In addition, the photogrammetric map does not include mounds under a meter in height, which are the vast majority identied on the photogrammetric images (Yadeun 1975, p. 15), and likely represent residential structures. The paucity of visible structural remains has hampered efforts to estimate Tulas population at its height. Healan and Cobean (Healan 1989, p. 245) suggest a minimal population of 60,000 persons, a gure initially proposed by Stoutamire (1975) based on Tulas overall size, then estimated at 12 km2, and Sanders and Prices (1967) minimum urban density gure of 5,000 persons/km2. Other estimates, including Yadeuns (1975, p. 24) gure of 19,00035,000 and Diehls (1981, p. 284) gure of 32,00037,000, assume a smaller settlement and lower density than the survey data suggest. Residential life Residential structures have been encountered in excavations in at least 22 different localities within the ancient city (Fig. 7) and are the subject of several relatively detailed studies (Healan 1989, 1993, 2009a; Paredes 1990). Construction utilized the same methods and materials seen at Tula Grande but with greater use of adobe, featuring exterior walls of mud-mortared stone foundations overlain by courses of adobe blocks. Residential structures exhibit considerable variability in quality of construction, spaciousness, and use of plaster, paint, and other decorative elements that may reect differential status. Most of the 22 localities show clustered arrangements of rooms or whole buildings interpreted to be residential compounds that housed multiple families (Healan 2009a), some examples of which are shown in Fig. 8. I have previously characterized these as two distinct types: house compounds, or house groups, in which each component family occupied a separate building or house, and apartment compounds, in which each occupied a portion of a single building. In retrospect this distinction is probably of limited value, in part because the two are often not easy to distinguish, particularly with limited exposure. The clearest examples of apartment

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

67

Fig. 8 Plans of selected residential structures from various localities excavated at Tula. Letters refer to localities listed in Fig. 7

compounds at Tula are spacious, well-built structures with plaster-covered and possibly painted oors and walls that suggest elite residences, three of which are located within the monumental precinct (e.g., Figs. 7 and 8, a, b). House compounds, of which the best examples include three juxtaposed compounds exposed in the canal locality (Fig. 8, g), show considerable variability in form and quality, even among structures within individual compounds. A common feature in both house and apartment compounds is a centrally located interior or exterior courtyard that apparently served as common space and the focus of activity involving the entire compound. That these 22 localities were residential in function is indicated by associated artifacts and features that include utilitarian pottery, metates, hearths, and in situ braziers. In the canal locality, ve houses denitely contained hearths, while

123

68

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

possible food preparation areas, identied by whole metates and associated pottery vessels, were generally located in and around exterior courtyards (Healan 2009a, g. 4.5). The spatial and contextual segregation of possible cooking versus food preparation areas suggests that cooking and presumably eating were largely familyspecic activities while some food preparation was commonly performed outdoors, seemingly in the company of other families engaged in the same activity. Braziers, censers, and human gurines suggest household-level ritual activity, while ritual activity at a higher level is indicated by structures interpreted as altars in the courtyards of many residential compounds. Their central prominent location suggests activities that involved all member households, and at least three altars containing human burials suggest veneration of a common ancestor and the likelihood that the component families were related. A temple/pyramid in the canal locality may indicate ritual activity at the local neighborhood level. Economy and subsistence The most detailed information on diet and subsistence comes from rural sites in Tulas hinterland (see below), but maize and amaranth were encountered at several lez and Montufar 1980). localities within the city (Diehl 1981, p. 287; Gonza Metates recovered from many of Tulas excavated residential compounds suggest grinding of maize prepared by nixtamalization, probably the chief form in which maize was consumed in prehispanic Mesoamerica. The consumption of nixtamal at Tula and the Tula region is indicated by remains of pozol (i.e., balls of maize lez 1999, p. 147; Mastache et al. 2002, kernels), pozole, and possibly tamales (Gonza pp. 242243). Surprisingly, ceramic griddles (comales) used in the preparation of tortillas from ground nixtamal are infrequent in both the city and the hinterland compared to their relatively high frequency at contemporaneous sites in the Basin of Mexico. This led Mastache et al. (2002, pp. 234, 243) to suggest that cazuelas or some other vessel may have been used for this purpose, or, more intriguingly, that tortillas were not the principal form in which maize was consumed at Tula. It is reasonable to assume that some portion of Tulas residents were farmers, although the large basalt and rhyolite tools found at rural sites that may have been used in agricultural activity do not appear to have been part of the urban household assemblage. As discussed below, however, it is unlikely that the compounds in these 22 localities are a representative sample of Tulas households. Craft production Evidence for craft production consists largely of by-products of manufacture recovered in both excavation and survey. The most abundant evidence involves two utilitarian craft activities, obsidian core/blade and ceramic vessel production. Obsidian core/blade production Obsidian artifacts are second only to pottery sherds in abundance at Tula, and the vast majority, perhaps 9599%, consists of segments of prismatic blades

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

69

intentionally broken for uses that probably involved hafting (Healan 1992a, p. 451). Tulas earliest (Prado/Corral) settlement obtained most of its obsidian from the cuaro (Michoaca n) source c. 150 km to the west (Fig. 1, C). Over Ucareo-Zinape time Tula came to rely increasingly on the Pachuca (Hidalgo) source c. 70 km to the east (Fig. 1, D), constituting 8095% of Tulas obsidian by the Late Tollan phase. Probable obsidian production loci at Tula came to light when a surface survey encountered several anomalous concentrations of core/blade debitage in the eastern portion of the city (Fig. 7). A more systematic survey (Pastrana 1977) revealed numerous localized hot spots presumed to mark individual production loci, which subsequent excavations exposed at two localities within the larger surface concentrations. Excavations at the Cruz locality (Fig. 7, H) partially exposed a workshop that contained distinct living, working, and refuse dumping areas (Healan 1986; Healan et al. 1983) and produced prismatic cores and blades from imported polyhedral (percussion) cores (Healan 2002, 2003). Obsidian residue indicate that the actual core/blade reduction loci were located outdoors (Healan 1997), although core platform grinding appears to have taken place inside the residential compound (Healan 2009b). Both the residential compound and the outdoor work area were relatively free of production waste, most of which was encountered in a peripheral refuse dump underlying the highest surface obsidian densities in the locality. This suggests that surface hot spots generally mark dumps rather than actual work sites, although the two were probably not very far apart (Healan 1992b). A second core/ ndez 1986, 1994) was excavated at the Vivero locality to the blade workshop (Ferna north (Figs. 7 and 8, f). Unlike the Cruz locality, the Vivero work areas appear to have been located inside rooms and patios of the residential compound. Pottery production No evidence of pottery production loci was encountered in either the Missouri project or the Proyecto Tula urban surveys. However, during systematic reexamination of the sites boundaries, Mastache and Crespo (1982; Crespo and Mastache 1973; Mastache et al. 2002, pp. 167169) encountered overred and warped sherds and other wasters over an area of about 2.5 km2 along the extreme eastern edge of the site (Fig. 7), which they interpreted as a potters barrio. Highway salvage excavations in the U98 locality near the north end (Fig. 7, n) partially exposed a residential compound containing numerous wasters and other kiln furniture. This included a partially intact updraft kiln and loose, vitried adobe blocks presumed to ndez Reyes et al. 1999). have been parts of other kilns destroyed by plowing (Herna Of particular interest was the recovery of numerous fragments of red ceramic molds apparently used to make shallow bowls and dishes that form a major component of the Tollan phase ceramic assemblage. Associated wasters indicate that the U98 locality produced at least seven major Tollan phase ceramic types. While these are mostly various forms of plates and bowls, they embrace a wide variety of styles, forms, and pastes, including representatives of three different ceramic wares dened by Cobean. The locality apparently also engaged in limited manufacture of ceramic gurines, spindle whorls, and architectural decorative elements.

123

70

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

The localitys ceramic assemblage provides support for the proposed Early Tollan/Late Tollan phase division based on production rather than consumption. In the lowest levels, ceramic production involved mainly two types, Proa and Joroba, both of which are diagnostic Early Tollan types. In the upper levels, production involved principally other Tollan phase types, including Jara, the single most diagnostic Late Tollan type. Other craft production Possible production areas for mold-made ceramic (Mazapan) human gurines are indicated by surface concentrations of gurine fragments, including one gurine mold fragment in the northeastern portion of the city. Nearby is a surface concentration of obsidian unifaces (scrapers) that given the absence of debitage, suggests activities involving use rather than manufacture (Pastrana 1977). Evidence of possible tecali (travertine) vessel manufacture at Tula was previously reported by Castillo (1970). Additional evidence in the form of cylindrical drill plugs of tecali, a by-product of the drilling-out stage of vessel manufacture, was recovered in the Missouri project survey and in excavation at the canal locality (Diehl and Stroh 1978). The relatively small number (19) recovered in the latter locality and the absence of nished or unnished vessels suggest that the plugs were obtained elsewhere and reused in some fashion. On the other hand, 13 of 17 tecali plugs recovered in surface survey came from the monumental precinct north and west of Tula Grande, suggesting that this may have been an area where tecali vessel manufacture occurred. As noted above, elite residences may have been located in this area, tecali vessel manufacture may have been an activity associated with elite households, similar to high craft activities recently identied at Aguateca, Guatemala (Aoyama 2007; Inomata 2001) and Teotihuacan (Manzanilla 2006). Alternatively, tecali vessels may have been produced by nonelite craft specialists who were tethered to elite households, or perhaps these drill plugs are reused objects as was suggested for those in the canal locality. Nine of 36 spindle whorls recovered in the Missouri project survey are likewise clustered in the monumental precinct, suggesting cloth production, which was an important activity among the Aztec elite classes (Evans 2001). Evidence for other utilitarian craft activities at Tula include salt making, as indicated by salt-pan fragments recovered from around El Salitre marsh (Yadeun 1975, p. 29, g. 57) and the discovery of what appears to be a kiln where ceramic tubes used to drain or transport water were red (Healan 1989, pp. 254259). Discussion The relatively high quality of many of the residential compounds excavated to date, along with other indicators of afuence, including a cache of Tohil plumbate and Central American polychrome vessels in the canal locality (Diehl et al. 1974), suggest they were of relatively high status. It must not be assumed, however, that these 22 localities are representative of Tulas households because a disproportionately large number of them are from the central portion of the city (Fig. 7). None are from the fringe where lower-status individuals may have lived. Moreover,

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

71

in many localities, excavators intentionally selected prominent surface mounds that are likely associated with more substantial architectural remains of higher-status households. Thus the sample of localities excavated to date is probably biased towards relatively afuent households. This may explain Sanders and Santleys assertion (1983, p. 268) that Tulas populace appears to have been mostly nonfood producers, which I believe is unlikely. Craft production appears to have occurred generally in a domestic setting, which agrees with other evidence that household-based craft production was the norm in Mesoamerica (Feinman and Nicholas 2000). While some was probably nonspecialized activity engaged in by most households for their own consumption, ceramic and lithic production was more specialized and involved relatively few of Tulas households. This embodies the concept of workshop as the term has come to be used and is well illustrated by refuse dumps in the Cruz locality that show individual deposits containing mixed core/blade debitage and domestic refuse (Healan 2009b, g. 5). Surprisingly, it appears that the Cruz locality obsidian workshop engaged in a low volume of production, estimated at less than one core reduced per day (Healan 1992a, p. 453). Its location in one of the densest hot spots within the larger obsidian surface concentration suggests that a low volume was characteristic of the entire production zone. Similarly, low output was indicated for three core/blade workshops recently excavated at Xochicalco (Hirth 2006, table 8.5). This also may be true of Tulas ceramic workshops given the small size and small number of kilns in the U98 locality; it seems unlikely that the larger ceramic production zone would have escaped detection in two previous surveys had there been more substantial surface evidence. While the prospect of numerous workshops, each engaged in a low volume of production, seems counterintuitive, there is evidence that both ceramic and lithic workshops engaged in multiple craft activities, or multicrafting (Feinman and Nicholas 2000, p. 136; Hirth 2006, p. 276), apparently a common practice in prehispanic Mesoamerica (Hirth 2009). The Cruz locality obsidian workshop also contained evidence of the manufacture of shell and bone objects and various items made from prismatic blades, most notably trilobal eccentrics (Stocker and Spence 1973), while the U98 ceramic workshop also manufactured gurines, spindle whorls, and architectural decorative elements. Other possible evidence of multicrafting includes the surface concentration of obsidian unifaces in the same general area where there is evidence of gurine production. It is likely that evidence for other craft production at Tula went undetected, just as pottery production did, at least initially. Noting the small volume of extant craft production, however, it appears unlikely to have been a major source of wealth for the city. On the contrary, Tula was probably dependent upon its hinterland for much of what it consumed, as detailed below.

History of settlement of Tula and the Tula region Knowledge of Tulas settlement history comes from excavation at Tula and other sites and from regional survey. Of particular importance is Mastaches (1996a;

123

72

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

Mastache et al. 2002) intensive survey of the immediate region around Tula that grew out of a preliminary survey conducted as part of the Proyecto Tula (Mastache and Crespo 1974, 1982). Mastaches intensive survey covered the area within a 17-km radius of the ancient city, hereafter referred to as the survey area. Earliest settlement The earliest evidence of settlement consists of Early/Middle Formative pottery recovered from construction sites in downtown Tula de Allende in 1977 and 2008 (L. Gamboa, personal communication 2008; Mastache and Crespo 1982, pp. 1317). These remains, including a burial, suggest an Early/Middle Formative period settlement of unknown size. The earliest well-dened settlements are Late Formative, with four sites containing predominantly Ticoman III ceramics (Mastache et al. 2002, p. 44). Three of the four sites are small settlements, while the other, designated La Loma, covers c. 15 ha of a mesa at the south end of the survey area (Fig. 2, A). Exploratory excavations in La Lomas ceremonial center (Cook de Leonard et al. 1956) cuaro tradition of southern encountered burials with ceramics of the Chup cuaro Guanajuato. Subsequent excavations (Cobean 1974) revealed that Chup ceramics are not limited to burials and in fact constitute as much as 5% of the decorated pottery at the site (R. Cobean, personal communication 2006). If La Loma were a regional center, its sustaining area must have included more than the three small sites identied in survey; additional settlements may lie beneath alluvium or some of the later Classic period settlements. However, given its location, La Lomas supporting area may be the northern part of the Basin of Mexico immediately to the south (Fig. 1), where there are other sites with both cuaro ceramics (McBride 1969, 1974). Its location at the apex of Ticoman and Chup an area of major settlement to the south is consistent with that for gateway communities as dened by Hirth (1978). Classic period settlement phase, substantial settlement appeared in the During the Classic period Chingu survey area, exhibiting diagnostic Tzacualli through Metepec phase ceramics of Classic Teotihuacan located less than 70 km to the southeast (Fig. 1, B). The vast majority of settlements are what Mastache (1996a) calls dispersed sites, i.e., surface scatters that may represent homesteads, temporary camps, or other small sites. There also are 12 large, nucleated sites with dense surface artifact cover and , covers an area of over monumental architecture, the largest of which, Chingu 2 2.5 km (Fig. 2, B). phase sites suggests a The variability in size and complexity among the Chingu at the top. The latter site has possible four-tiered settlement hierarchy, with Chingu been heavily damaged but not before it was systematically investigated by INAHs az 1980). Numerous rectangular stone fragments suggest the use Proyecto Tula (D of the distinctive talud-tablero facade characteristic of Teotihuacan monumental architecture. The site contained c. 475 visible mounds, some of which are

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

73

rectangular in form and whose orientation approximates the 15300 east of north az 1980, g. 3). These mounds include two orientation of Teotihuacan (D rectangular enclosures, the largest of which, La Campana, is comparable in form to Teotihuacans Ciudadela, although smaller, and includes a prominent interior azs map suggests that mound like the Ciudadelas Feathered Serpent Pyramid. D structures were arranged along northsouth and eastwest axes that intersect in front of La Campana, as do the northsouth and eastwest avenues in front of the Ciudadela at Teotihuacan. Notable differences between the two sites include the of counterparts of Teotihuacans Sun and Moon Pyramids, which absence at Chingu may underscore their construction and perhaps greater importance before Teotihuacan became the center of a macroregional empire. Conversely, a second Ciudadela-like compound immediately east of La Campana has no obvious counterpart at Teotihuacan. phase settlement hierarchy includes three sites, The second level of the Chingu each about 80 ha, located north of Tula, at least one of which also exhibits evidence of talud/tablero architecture and a Ciudadela-like enclosure. The third level includes eight smaller nucleated sites of about 1015 ha, some of which contain monumental architecture. All eight are situated in the southern and eastern periphery of the survey area and include two sites with a strong Oaxacan afliation, as described below. The fourth level includes the numerous dispersed sites already noted. phase occupation at the There is currently no evidence for any signicant Chingu site of Tula itself, despite its favorable location at the conuence of two rivers and the relatively high density of settlement in the immediate vicinity, including a level 2 site less than 2 km to the north. phase settlement was under the control There seems little doubt that the Chingu of Teotihuacan. Indeed, its sheer magnitude compared to the previous Late Formative settlement suggests outright colonization by those with close ties to Teotihuacan. Similar instances of intrusive settlement systems attributed to Teotihuacan have been documented in Morelos (Angulo and Hirth 1981; Hirth a Cook 1981), and the Toluca Valley (Sugiura and Angulo 1981), Puebla (Garc appear to have been made in the image of 1993), although many aspects of Chingu Teotihuacan. Given the extensive calcareous deposits in the immediate region and the considerable volume of lime used at Teotihuacan (Barba and Frunz 1999), Mastache et al. (2002, p. 59) suggest that lime exploitation was a major activity of phase settlement in the region. This was conrmed by recent X-ray the Chingu uorescence (XRF) analysis that identied these deposits as the source of lime for at least one Teotihuacan apartment compound (Barba et al. 2009). Likewise, the agriculturally productive alluvial plain may have been an important resource, phase sites are situated along two irrigation particularly as a number of Chingu canals that are at least as old as the colonial period (Mastache and Crespo 1974; itself is situated at the terminus of Mastache et al. 2002, pp. 35, 59). Indeed, Chingu one of these canals (Mastache et al. 2002, g. 4.2). Thus it is reasonable to suggest phase settlement was the exploitation of lime and that a major activity of the Chingu agricultural resources, presumably for the Teotihuacan state.

123

74

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

Numerous sites with Teotihuacan ceramics also are present in the southern portion of the Valle del Mezquital along Tulas northern ank (Fournier 2007, pez Aguilar 1994; Lo pez Aguilar et al. 1998, pp. 3032) and are pp. 9396; Lo likewise interpreted as outright colonization by Teotihuacan, possibly for stone and forest products (Polgar 1998, pp. 4445). This region includes the Pachuca obsidian source (Fig. 1, D), which various authors have suggested was under Teotihuacans pez Aguilar et al. (1998) suggest that these sites, some of which control. Lo phase contained low frequencies of Oaxacan ceramics, were an extension of Chingu settlement from the Tula region, a reasonable assumption given the size of Chingu and its intermediate location. The Teotihuacan-related occupation is conned to the southern portion of the Valle del Mezquital, which may indicate the northern limits of rainfall agriculture. There is evidence, however, of preexisting settlements to the pez Aguilar et al. 1998, north that may have restricted Teotihuacan expansion (Lo pp. 2931). These settlements contain ceramics of the Xajay tradition, associated o that span the Classic and Epiclassic periods (Nalda with sites in the eastern Baj 1975, 1991). Teotihuacan and the Zapotec diaspora in the Tula region phase sites contain ceramics of Oaxacan afliation in addition to Many Chingu , where they are 7% of decorated diagnostic Teotihuacan ceramics including Chingu az 1981, p. 109). Oaxacan pottery constitutes 5060% of identiable ceramics (D ceramics at two level 3 sites, Acoculco and El Tesoro, which occupy nonadjacent o Tula near the southern limits of the region hilltops along a tributary of the R n II and IIIa (Fig. 2, C, D). Identiable Oaxacan ceramics are diagnostic Monte Alba types (Caso et al. 1967), and some appear to be locally made (Crespo and Mastache 1981, p. 102; Mastache et al. 2002, p. 57). At least two Zapotec-style tombs have been identied at El Tesoro, one of which was excavated, yielding skeletal remains and grave goods that included a variety of ndez 1994). The tomb was a narrow, slab-lined trench Oaxacan ceramics (Herna n II tombs, with steps at one end and a slab roof and similar in form to Monte Alba oor. Two other possible tombs were encountered in the wake of a recent housing development at El Tesoro (R. Cobean, personal communication 2009). El Tesoro and Acoculco may have been Zapotec enclaves given their predominantly Zapotec ceramic assemblage and funerary architecture. Mastache et al. (2002, pp. 5759) suggest that the Zapotec presence in the Tula region is likely linked to Teotihuacan, given the well-known Zapotec enclave there (Millon 1973; Spence 1992). This may explain the location of these two sites at the northern threshold of the Basin of Mexico, although there are other possible explanations for their location, noted below. The Tula region thus provides additional evidence of systematic interaction between central Mexico and the Valley of Oaxaca, although the reasons for what Spence (2005) has termed a Zapotec diaspora in central Mexico are not known. Sanders (personal communication 1976, cited in Crespo and Mastache 1981, p. 103) suggests that at least some of these immigrants may have been specialists in the production of lime, a craft that in Oaxaca goes back to the Early Formative period (Flannery and Marcus 1994). In this regard, the location of

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

75

El Tesoro and Acoculco may be explained by their proximity to the calcareous deposits in the southern portion of the survey area. Classic to Epiclassic The Classic/Epiclassic period transition in central Mexico is marked by two events: (1) the demise of Teotihuacan by the end of the Metepec phase and (2) the appearance of a distinctive ceramic complex known as Coyotlatelco throughout much of central Mexico. It was also during this time that initial settlement occurred at Tula. The demise of Teotihuacan was felt throughout Mesoamerica (Diehl and Berlo 1989) and is the dening event of the Classic/Epiclassic boundary (Diehl and Berlo nez Moreno 1959; Webb 1978). Although evidence of burning and other 1989; Jime destruction along the Street of the Dead suggests a sudden, rather violent end (Millon 1996), Teotihuacan may already have been in a state of decline by the pez Perez et al. 2006; Rattray 1996, p. 216). Until recently, the Xolalpan phase (Lo end of Metepec phase Teotihuacan was dated to c. A.D. 750 (Millon 1973, g. 12), but over a decade ago at least two researchers (Cowgill 1996; Rattray 1996, 2001) proposed pushing this date back at least a century (Fig. 4). Recent evidence (Manzanilla 2003, p. 94; Rattray 2006, p. 208) that at least some of the widespread burning occurred at the end of the Xolalpan phase provides additional support for an earlier end date. This revision appears to have gained general acceptance with relatively little fanfare or controversy, despite its profound impact on the timing of and relationships among various developments in the Classic and Epiclassic periods (Diehl and Berlo 1989; Manzanilla 2005; Mountjoy and Brockington 1987; Solar 2006). Despite its demise, there was occupation at Teotihuacan during the Epiclassic period that, like many other sites in the Basin of Mexico, is associated with Coyotlatelco ceramics. The size and nature of the Epiclassic occupation, however, still spark disagreement. Some investigators (e.g., Cowgill 1996, p. 330; Diehl 1989b, p. 12; Sanders 1986; Sanders et al. 1979, p. 129; Sugiura 2006, p. 148) believe that Epiclassic Teotihuacan not only functioned as a coherent settlement but a Cha vez et al. 2006; was still the largest settlement in the basin. Others (Garc Gomez and Cabrera 2006; Rattray 1996, pp. 216217, 2006, p. 206) argue that Teotihuacan was a discontinuous landscape of hamlets or villages with no central organization and large unoccupied zones in between (Rattray 1996, p. 217). Proponents of a substantial settlement appear to base their opinion on the surface distribution of Coyotlatelco ceramics, interpreted as evidence of relatively dense but less extensive occupation. On the other hand, opponents base their opinion on excavations at various localities that show either a lack of Epiclassic occupation or one involving insubstantial construction or reoccupation of Classic structures. First identied in excavations near Atzcapotzalco in the basin (Tozzer 1921), Coyotlatelcos Epiclassic dating is based largely on its occurrence in post-Metepec contexts at Teotihuacan (e.g., Armillas 1950, p. 56; Sejourne 1956) and in stratigraphically early contexts at Tula (Acosta 1945, pp. 5356). Rattray (1966) provided the rst denitive study of Coyotlatelco pottery, while more recent

123

76

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

comprehensive studies include those of Cobean (1990), Nichols and McCullough (1986), and Solar (2006). There is considerable debate over what is Coyotlatelco (e.g., Gaxiola 2006). Its chief characteristics include red-painted geometric and other designs applied to the interior and/or exterior of natural or cream-slipped hemispherical and at bottom bowls. Painted vessels are typically highly burnished and often have tripodal conical supports. Coyotlatelco assemblages also include undecorated monochrome vessels, comales, pipes, and censers. There is currently a lively debate regarding the origins of Coyotlatelco ceramics, and since the Tula region plays a signicant role in the debate, this is discussed below after the following section. Epiclassic settlement in the Tula region phase sites in the survey area were abandoned by the end of Virtually all Chingu Teotihuacans Metepec phase, although abandonment had apparently been underway since the Xolalpan phase (Mastache and Cobean 1989, p. 51). Abandonment of Teotihuacan-associated sites also occurred in the Valle del Mezquital (Cervantes and Torres 1991; Fournier 2007, p. 96; Polgar 1998, pp. 4548; Torres et al. 1999, p. 82). As in the Basin of Mexico, Epiclassic settlement in the Tula region is associated with the Coyotlatelco ceramic complex. The majority are dispersed sites, plus nine large, nucleated settlements, including Tula Chico. The Epiclassic and preceding phase settlement systems are notably different, with the latter Classic period Chingu occupying the center of the survey area while the ten Epiclassic nucleated settlements are situated on hilltops or elevated terrain mostly along the periphery. Although both Classic and Epiclassic dispersed sites were encountered on the alluvial plain, few sites exhibit both components (Mastache et al. 2002, p. 45). This mutually exclusive distribution suggests wholesale discontinuity between the Classic and Epiclassic settlement systems, perhaps reecting the breakup of the Teotihuacan political system. It also could indicate that the two settlement systems overlapped in time, as discussed below. In a systematic study over several decades (Cobean 1978, 1982, 1990; Cobean and Mastache 1989; Cobean et al. 1981; Mastache and Cobean 1989, 1990; Mastache et al. 2002), Cobean and Mastache divided the Coyotlatelco occupation in the Tula region into three successive (La Mesa, Prado, and Corral) phases (Fig. 4), of which the earliest (La Mesa) phase is believed to include all nine nucleated hilltop settlements except Tula Chico. These settlements include the site of La Mesa itself (Fig. 2, E), which covered an area of about 1 km2 (Bonl 2005; Mastache and Cobean 1989). La Mesa contains three distinct monumental centers anked by terraces containing both rectangular and circular structures, the latter uncommon in central Mexico. Many of the other La Mesa phase settlements exhibit monumental architecture and evidence of terracing, although none, including La Mesa, appear to have been densely occupied. Another nucleated Coyotlatelco hilltop settlement, known variously as Cerro la Ahumada and Mesa Grande (Fig. 2, F) was encountered during the Zumpango region survey immediately to the south

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

77

(Parsons 2008, pp. 174184; Sanders et al. 1979, p. 131), and may be the tenth and southernmost La Mesa phase hilltop settlement. The earlier dating of the La Mesa phase is based on ceramics whose painted motifs were perceived as simpler in form and execution than those of the subsequent Prado and Corral phases and of Coyotlatelco sites in the Basin of Mexico, thus interpreted as developmentally and temporally earlier (Cobean et al. 1981, p. 193; Mastache and Cobean 1989, p. 56). Although the La Mesa phase includes all ten nucleated hilltop settlements except Tula Chico, only two others, Cerro Magoni (Mastache and Cobean 1990, Mastache et al. 2002, p. 68) and Cerro Elefante nez 1994), have been explored by excavation. Surface pottery from all nine (Mart La Mesa phase sites apparently exhibit notable differences in form and decoration, including unique types that constitute at least 20% of the ceramics at each site (R. Cobean, personal communication 2008). Differences also are seen in site layout, architectural characteristics, and lithic assemblages (Mastache et al. 2002, p. 69; Rees 1990). Mastache and Cobean interpret the La Mesa phase settlement as a series of largely independent polities rather than a single integrated system, a pattern reminiscent of the Tezoyuca phase hilltop centers and surrounding settlements on the periphery of the Teotihuacan Valley during the Terminal Formative period (Sanders et al. 1979, pp. 104105). Excavation suggests that at least two hilltop settlements, La Mesa and Cerro Magoni, were single component sites, and Mastache and Cobean proposed from surface ceramics that the other La Mesa phase hilltop sites were as well. Thus the two subsequent Coyotlatelco-related (Prado and Corral) phases are restricted to Tula Chico and presumably the dispersed sites in the surrounding area. Epiclassic/Coyotlatelco settlement at Tula Chico Coyotlatelco ceramics were rst identied at Tula by Acosta (1945) in excavations at Tula Grande and apparently near Tula Chico. In both the Missouri and Proyecto Tula surface surveys, Coyotlatelco surface ceramics clustered around Tula Chico (Healan and Stoutamire 1989, g. 13.6; Yadeun 1975, g. 19), leading investigators to interpret it as the monumental center for the earliest settlement. Additional investigations have been conducted at Tula Chico in recent decades, virtually all by rez 1989; Mastache et al. Cobean and Mastache (Cobean 1982; Cobean and Sua 2009). Tula Chico contains a central plaza measuring c. 75 m eastwest and is anked by several pyramids, two ball courts, and large platforms comparable to those of Tula Grande (Fig. 3; see also Mastache et al. 2009, g. 19). Despite their similarity in layout, Tula Chico and Tula Grande differ in several ways, including the approximate northsouth orientation of the former versus the c. 17 east of north orientation of the latter. Equally distinctive is that Tula Chicos two principal pyramids are situated side by side at the north end, an unusual arrangement somewhat like the twin-temple/pyramidal complex of Tenochtitlans Templo Mayor. According to Mastache and Cobean, Tula Chicos ceramics resemble those described for Coyotlatelco sites in the Basin of Mexico (Blanton and Parsons 1971;

123

78

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

Nichols and McCollough 1986; Rattray 1966; Tozzer 1921) more than they do the La Mesa complex, sufciently so to merit their denition as a separate complex that they believe postdates the La Mesa phase. Two such complexes and phases (Prado and Corral) were dened, although most of Tulas Epiclassic settlement pertains to the Corral phase, with Prado as an earlier variant. The bulk of the ceramics used to dene these two phases came from four exploratory pits excavated by INAH at Tula Chico, three of which were located within Tula Chico and another located c. 180 m to the southeast (Cobean 1982, g. 2). In all three pits inside Tula Chico, Coyotlatelco ceramics predominated throughout, with small quantities of Tollan phase ceramics limited to the uppermost levels (gs. 79). This agrees with the relatively small quantity of Tollan complex ceramics recovered from Tula Chico in surface survey, suggesting the monumental center was unoccupied during the Tollan phase. In all four pits, Cobean identied a distinctive subassemblage co-occurring with Coyotlatelco ceramics that was most common in the lowest levels. This subassemblage, consisting of decorated serving vessels with no examples of utilitarian vessel forms (Cervantes and Fournier 1994, p. 110; Cobean 1982, p. 64), was used to dene an earlier ceramic complex. Designated the Prado complex and phase, this appeared to stratigraphically precede the full-blown Coyotlatelco manifestation during the Corral phase (Cobean and Mastache 1989, p. 42). Cobean (1990, p. 44) subsequently identied Prado in the lowest levels of two exploratory pits previously excavated by INAH at Tula Chico (Matos 1974a, gs. 8, 10) that had been described as Teotihuacanoid. It must be emphasized that the Prado complex consists of the above subassemblage, hereafter referred to as Prado ceramics, plus the suite of Coyotlatelco ceramic types that dene the Corral complex. Even in levels where Prado ceramics are at peak popularity, Coyotlatelco ceramics are still more numerous, and while Prado ceramics sharply decline in frequency in subsequent levels, small amounts were present even in the highest levels. Thus the distinction between the Prado and Corral phases is one of relative frequency and therefore somewhat arbitrary. This problem might be resolved if a larger study of Prado and Corral ceramics permitted the subdivision of one or more existing types into early and late variants by which the two complexes could be differentiated. Failing this, it may be preferable to consider Prado and Corral as early and late subphases, respectively, of a single (Corral) phase. Outside Tula Chico, Prado vessels were recovered from burials in salvage excavations by INAH near the Museo locality (Paredes 2005, pp. 211214). Few Prado ceramics were encountered in surface survey inside the city (Healan and Stoutamire 1989, g. 13.7) and few were encountered in regional survey (Cobean 1982, p. 66). Recently, however, Prado ceramics were identied at Chapantongo os 2007), an Epiclassic site about 2.5 km2 (Fournier 2007; Fournier and Bolan located c. 27 km northwest of Tula, whose ceramic assemblage includes most of Tulas Corral and Prado phase ceramic types. Unlike Tula Chico, Prado ceramics at Chapantongo show no variation in relative frequency over time (Cervantes and Fournier 1994, p. 108), which could indicate a relatively brief temporal duration.

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

79

While the extent of Tulas Prado phase settlement is unknown, the subsequent Corral phase settlement has been estimated as between 3 and 6 km2 (Cobean 1982; Mastache and Crespo 1982, p. 23; Yadeun 1975, p. 22). Outside Tula Chico, Corral phase occupation at Tula has been identied in excavations at the El Corral locality (Cobean 1990, p. 141) and the Museo and Cerro Malinche localities (Paredes 2005, pp. 209213). It is reasonable to assume that Corral phase settlement extended into Tulas monumental precinct, possibly including the area later occupied by Tula Grande given its commanding location. Various authors (Mastache and Crespo 1982, pp. 2324; Mastache et al. 2002, pp. 72, 129) have speculated on the existence of a Corral phase monumental center at Tula Grande given the recovery of Coyotlatelco ceramics from the lowest levels of several excavations there (Acosta 1945, p. 53; Mastache et al. 2002, p. 129). As discussed below, however, the earliest construction levels in which Coyotlatelco ceramics have been encountered at Tula Grande appear to date to the Terminal Corral rather than Corral phase, and it appears that the two monumental centers did not overlap in time. Recent investigations at Tula Chico During 2002 and 2003, Cobean and Mastache conducted excavations on the south facade and superstructure of the largest pyramid on the north side of Tula Chico. The superstructure, which had been burned in prehispanic times, was dated to the rez et al. Corral phase based on associated ceramics (Mastache et al. 2009; Sua 2007). Associated sculpture includes a relief panel depicting a reclining gure (Mastache et al 2009, g. 20), essentially identical in style, dress, and accoutrements to those from Building 3 at Tula Grande, thus extending one of Tula Grandes signature monumental art forms back into the Corral phase. Evidence of additional iconographic continuity between Tula Chico and Tula Grande was encountered in excavations in the southwest corner of Tula Chicos plaza, where sculptural fragments and architectural remains associated with Prado complex ceramics were encountered beneath more than a meter of rock ll that underlay the plaza (Mastache et al. 2009, g. 22). This included a relief panel fragment showing the foot and lower leg of a reclining personage, thereby extending this art form back into the Prado phase. Chronological issues According to Mastache and Cobean, Epiclassic settlement in the Tula region evolved from a landscape of small, competing polities to a single integrated system centered around Tula Chico, with an accompanying shift from largely peripheral, hilltop settlements to the alluvial plain. The proposed earlier dating of the La Mesa ` vis both the Prado/Corral phases and Coyotlatelco assemblages in the phase vis a Basin of Mexico raises the possibility that the former may have overlapped in time phase, Teotihuacan-associated settlement system. This also is with the Chingu suggested by the strikingly complementary distribution of the La Mesa and Chingu phase settlements that may explain why the former settlement system surrounds the area rather than occupying it (Mastache et al. 2002, p. 302). Overlap between

123

80

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

the two settlement systems would have obvious implications for the debate surrounding the origins of Coyotlatelco ceramics, discussed below. However, recently obtained radiocarbon dates for both La Mesa and Tula Chico (Fig. 5, aj) provide mixed results with respect to this issue. On the one hand, the two-sigma ranges for four of the ve samples from each of the two sites are os (2007, p. 511) strikingly similar, with almost total overlap. As Fournier and Bolan note, this provides no support for the premise that La Mesa and presumably the other La Mesa phase hilltop sites predate Tula Chico. At the same time, both sites have one date whose two-sigma range falls almost completely within the Classic period (Fig. 5, a, f). For Tula Chico, this date has stratigraphic integrity since it comes from ll beneath the plaza oor underlying the Ballcourt, while the other four dates are from stratigraphically later contexts associated with a later platform. Too few dates are involved, however, for overlap between Classic and Epiclassic settlement to be more than an interesting possibility. Tula and the origin of Coyotlatelco ceramics Although the debate regarding where, when, and how Coyotlatelco ceramics originated involves numerous points of discussion, it is often and somewhat inaccurately characterized as a dichotomy involving those who favor a nonlocal versus a local origin. Proponents of a nonlocal origin, originally proposed by nez Moreno (1959), Braniff (1972), and Rattray (1966), trace Coyotlatelco to Jime one or more red-on-buff ceramic traditions to the north and west as far away as the o region of Chalchihuites region of Zacatecas and Jalisco, or as near as the Baj taro (Fig. 1). Mastache and Cobean (1989, p. 65, southern Guanajuato and Quere 1990, p. 22; see also Cobean 1990, p. 500; Mastache 1996a, pp. 4750) favor a nonlocal origin, specically the Chalchihuites region given similarities in ceramics as well as architecture, settlement, and lithic assemblages. The primary reason given by Mastache for believing that the Chalchihuites region was the most likely source involves the disparity between the supposed abundance of Blanco Levantado o during the Epiclassic versus its absence in both the pottery in the Baj Chalchihiutes and Tula regions prior to the Early Postclassic period (Mastache et al. 2002, p. 71). However, several authors have recently noted that Blanco o (e.g., Levantado is likewise absent in much of the southern portion of the Baj Brambila and Crespo 2005, pp. 165167; C. Hernandez, personal communication 2009). The view that La Mesa phase sites were settled by immigrants from the Chalchihuites region has been soundly criticized by various authors (e.g., Fournier nez Betts 2006). Jime nez Betts notes that revised dating of et al. 2006; Jime Chalchihuites ceramic phases has made them contemporaries of the Coyotlatelco complex rather than earlier complexes from which the latter could have derived. os 2007, pp. 505509) question the validity Other authors (e.g., Fournier and Bolan of supposed architectural and other material ties between La Mesa phase and Chalchihiutes sites. In retrospect, the notion that the appearance of Coyotlatelco signals the arrival of peoples from over 500 km away seems unlikely, for these and

123

J Archaeol Res (2012) 20:53115

81

other reasons. At the same time, however, the settlement data strongly suggest that the Coyotlatelco settlements in the survey area were intrusive, as is discussed below. With respect to the other side of the debate, there are relatively few proponents of a purely local origin for Coyotlatelco (e.g., Dumond and Muller 1972, p. 1214; Sanders 2006, p. 190), who see its origins in red-on-buff ceramics at Teotihuacan or earlier traditions in the Basin of Mexico. Instead, there appears to be an emerging middle ground (e.g., Beekman and Christensen 2003; Fournier 2006, pp. 438439; pez Perez et al. 2006; Manzanilla 2005, p. 269; Sugiura 2006) that Gaxiola 2006; Lo sees Coyotlatelco as a fusion, hybridization, or syncretism of the preexisting Teotihuacan ceramic tradition with a nonlocal tradition possibly introduced by migrating populations, although more indirect forms of interaction also could have o is the most likely been responsible. As most of these authors note, the eastern Baj region of origin given its proximity (Fig. 1) and growing evidence of a rich and cuaro) widespread red-on-buff tradition that goes back to Late Formative (Chup o, particularly to the Tula region, times. Moreover, the proximity of the eastern Baj would facilitate regular interaction without necessarily involving migration or, if so, minimal population displacement. Prado and Corral ceramics have been recently taro by Saint-Charles and identied in burials at Cerro la Cruz in southern Quere quez (2006), who assert that one of the principal Prado ceramic types, Ana Enr a, is identical to Rojo Sobre Bayo El Mogote, a previously dened type Mar taro (Nalda 1975). common in southern Quere In addition, Coyotlatelco sites characteristically exhibit a lithic assemblage dominated by obsidian from the Ucareo obsidian source (Fig. 1, C) on the o (Healan 1997, table 1). Recent excavation of southeastern ank of the Baj habitation sites around the source (Healan 1997; Hernandez and Healan 2000) has documented a long-lived red-on-buff ceramic tradition (Hernandez 2000) whose origins go back to the Early/Classic period, as determined by recent chronometric dating (Hernandez and Healan n.d.). Post-Corral phase developments Abandonment and destruction of Tula Chico Survey and excavation reveal an absence of later construction or other occupation at Tula Chico itself, suggesting it was abandoned some time after the Corral phase. Recent exploration of structures on the north and east sides of Tula Chico rez encountered evidence of burning and intentional destruction (Cobean and Sua 1989). The discovery of a Terminal Corral ceramic assemblage on the oor of a burned structure atop the East Platform suggests the destruction occurred during the Terminal Corral phase. The destruction and abandonment appears to have been conned to Tula Chico itself given the presence of Tollan phase structures and ceramics in the immediate surrounding area. The apparent destruction and burning of Tula Chico was undoubtedly a major event, although continuity in ceramics and other traits suggests largely internal processes were involved. That Tula Chico remained in ruins as it was surrounded by the growing city, a situation not unlike the Acropolis surrounded by modern

123

82