Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Simple Procedure For Retrieval of A Cement-Retained Implant-Supported Crown: A Case Report

Uploaded by

University Malaya's Dental Sciences Research0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

48 views4 pagesRetrieval of cement-retained implant prostheses can be more demanding than retrieval of screw-retained prostheses. This case report describes a simple and predictable procedure to locate the abutment screw access openings of cementretained implant-supported crowns in cases of fractured ceramic veneer. A conventional periapical radiography image was captured using a digital camera, transferred to a computer, and manipulated using Microsoft Word document software to estimate the location of the abutment screw access.

Original Title

A simple procedure for retrieval of a cement-retained implant-supported crown: a case report

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRetrieval of cement-retained implant prostheses can be more demanding than retrieval of screw-retained prostheses. This case report describes a simple and predictable procedure to locate the abutment screw access openings of cementretained implant-supported crowns in cases of fractured ceramic veneer. A conventional periapical radiography image was captured using a digital camera, transferred to a computer, and manipulated using Microsoft Word document software to estimate the location of the abutment screw access.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

48 views4 pagesA Simple Procedure For Retrieval of A Cement-Retained Implant-Supported Crown: A Case Report

Uploaded by

University Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchRetrieval of cement-retained implant prostheses can be more demanding than retrieval of screw-retained prostheses. This case report describes a simple and predictable procedure to locate the abutment screw access openings of cementretained implant-supported crowns in cases of fractured ceramic veneer. A conventional periapical radiography image was captured using a digital camera, transferred to a computer, and manipulated using Microsoft Word document software to estimate the location of the abutment screw access.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

1

QUI NTESSENCE I NTERNATI ONAL

doi: ??.????/j.qi.a??????

A simple procedure for retrieval of a cement-retained

implant-supported crown: A case report

Muaiyed Mahmoud Buzayan, BDS, MClinDent

1

/Wan Adida Azina Binti Mahmood, BDS, MDSc

2

/

Norsiah Binti Yunus, BDS, MSc

3

Retrieval of cement-retained implant prostheses can be more

demanding than retrieval of screw-retained prostheses. This

case report describes a simple and predictable procedure to

locate the abutment screw access openings of cement-

retained implant-supported crowns in cases of fractured

ceramic veneer. A conventional periapical radiography image

was captured using a digital camera, transferred to a comput-

er, and manipulated using Microsoft Word document software

to estimate the location of the abutment screw access.

(Quintessence Int 201#;##:14; doi: ##.####/j.qi.a#####)

Key words: cement-retained, ceramic veneer fracture, implant-supported prosthesis

PROSTHODONTICS

Muaiyed Mahmoud

Buzayan

to retrieve a cement-retained prosthesis without aect-

ing the implant abutment and restoration compared to

a screw-retained implant restoration.

2,8

Unlike in natural

abutment teeth, conventional cements do not chemi-

cally adhere to metallic abutments. However, the

appropriate choice of cement should be made to pro-

vide adequate crown retention on the implant abut-

ment and at the same time allow for retrievability.

8-10

In

view of the many reports of abutment screw loosening

and ceramic veneer fracture,

11

various techniques have

been described in the literature to simplify the retrieval

of cement-retained implant crown restorations. Some

contingency plans to allow the identication of screw

access location and hence easy retrieval include incor-

porating a retrieval slot in the design

1,3

and staining the

occlusal surface of the ceramic restoration to indicate

the abutment screw location.

12

Crown sectioning at the

midfacial surface to break the cement seal before the

sectioned crown is retrieved,

13

however, involved pro-

longed chairside time. A more common method is to

locate the screw access by drilling and perforating a

section of the restoration using a bur.

14

The ability to

Implant-supported prostheses can be either screw- or

cement-retained,

1,2

and the choice of retention means

depends on the clinicians preference, the available

interridge space, esthetics, and cost.

2

Predictable

retrievability of implant-retained restorations is another

factor to be considered as a part of patient care,

2,3

where for maintenance purposes, the prosthesis may

need to be retrieved on many occasions. Screw reten-

tion allows easier retrievability; however, the range of

benets of cement-retained prostheses includes better

seating of the superstructure/framework,

4

less screw

loosening,

5

fewer problems related to occlusal screw

holes,

6

and fewer problems with ceramic strength

issues.

7

In terms of retrievability, it is more demanding

1

Lecturer, Department of Prosthodontics, Dental Faculty, University Of Tripoli,

Tripoli, Libya.

2

Associate Professor, Department of Prosthetic Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry,

University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

3

Professor, Department of Prosthetic Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of

Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Correspondence: Dr Muaiyed Mahmoud Buzayan, Department of Pros-

thodontics, Dental Faculty, University Of Tripoli, Tripoli, Libya. Email:

muaiyed_zyan@hotmail.com

2

QUI NTESSENCE I NTERNATI ONAL

Buzayan et al

doi: ??.????/j.qi.a??????

identify the approximate location of the screw access

opening in cement-retained implant-supported crowns

may eliminate laborious intraoral crown sectioning.

The purpose of this article is to describe a simple

and undemanding procedure making use of readily

available conventional periapical radiography to locate

the screw access opening of ceramic implant-sup-

ported crowns with fractured ceramic veneer. The

image was loaded onto a computer, and using readily

available software, the abutment screw location was

estimated by measuring the mesiodistal dimension of

the crown in relation to the adjacent teeth.

CLINICAL CASE

A 21-year-old female patient presented to the Depart-

ment of Prosthetic Dentistry, 3 months after a metal-

ceramic implant-supported crown was cemented,

replacing the mandibular right second premolar. She

was concerned with the crown restoration, which was

gradually chipping o, and had no other associated

symptoms (Fig 1). The patients dental record indicated

that a 4.5-mm diameter (bone level; SuperLine, Implan-

tium) implant had been inserted in the mandibular

right second premolar edentulous area. The metal-

ceramic crown was cemented using provisional

cement (TempBond, Kerr). A straight abutment was

used in this case. The most likely cause for the ceramic

veneer fracture in the present case was unsupported

ceramic as a result of an undercontoured and poorly

designed metal coping. The treatment plan included

replacement of the damaged crown and recementa-

tion of a new metal-ceramic crown on the existing

implant abutment (Fig 1).

Fig 2 Periapical radiograph of the implant-abutment junction

and the cemented metal ceramic-crown before editing.

Fig 3 With the help of the ruler, the image was enlarged such

that the implant shoulder measured 4.5 cm on the screen.

Fig 1 Partial veneer fracture of implant crown replacing the

mandibular right second premolar with an exposed metal coping.

3

QUI NTESSENCE I NTERNATI ONAL

Buzayan et al

doi: ??.????/j.qi.a??????

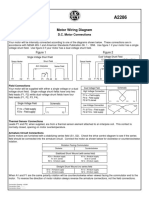

The location of the abutment screw was estimated

using a conventional intraoral periapical radiograph of

the implant taken post-cementation. A digital camera

(Canon EOS Digital Rebel; Canon) was used to capture

the image of the periapical radiograph with ash o/

autofocus settings. The image was loaded onto a com-

puter as a JPEG image and later imported into a Micro-

soft Word document le. The image was edited and

enlarged so that the radiographic image was approxi-

mately 4.5 cm wide at the implant shoulder (represent-

ing the actual 4.5-mm implant diameter) (Fig 2). On-

screen ruler software (Version 2.2, Kummailil J) was

used for this purpose (Fig 3).

In the same Word document le, a ready-made cyl-

inder shape was inserted and superimposed on the

radiographic image of the abutment screw. A similar

enlarging procedure was performed where the mesio-

distal length of the cylinder was enlarged to approxi-

mately 2.3 cm, representing the 2.3-mm diameter of

the abutment screw according to the manufacturer.

Once this length was established, the mesial and distal

lengths to the proximal surfaces of the respective ante-

rior and posterior adjacent teeth were established.

The mesiodistal distance between the mesial sur-

face of the cylinder and the proximal surface of the

adjacent rst premolar measured 2.6 cm, while the

distance between the distal surface of the cylinder to

the proximal surfaces of the rst molar was 3.4 cm

(Fig 4).

The estimated position of the screw access opening

was marked occlusally using a metal ruler. With a sharp

transmetal bur (Dentspy Maillefer), the metal coping

was penetrated to expose the sealer over the screw

head. A hand driver was used to unscrew the abut-

Fig 4 Cylinder shape outline of the estimated mesiodistal abut-

ment screw location.

Fig 5 The abutment screw was exposed.

Fig 6a Retrieved abutment-

crown assembly.

Fig 6b Metal coping sepa-

rated from the abutment.

2.3

3.4 2.6

4.5

4

QUI NTESSENCE I NTERNATI ONAL

Buzayan et al

doi: ??.????/j.qi.a??????

ment-crown assembly, which was easily separated

once out of the mouth (Figs 5 and 6). A new crown res-

toration was fabricated and cemented in place.

DISCUSSION

One advantage of this radiographic technique over

other methods that utilize a photographic image

15,16

is

that the intraoral periapical radiograph can be made

available even after cementation. With the technique of

Figueras-Alvarez et al,

15

two digital photographs of the

denitive cast precementation are required, indicating

that the procedure needs to be performed routinely

before the prosthesis is cemented. With the technique

of Daher and Morgano,

16

taking digital photographs of

the patient is time-consuming for both the patient and

the dental o ce sta, and it needs to be performed

routinely precementation. The present technique also

requires information on the implant system used,

which can easily be obtained from the website or prod-

uct catalogue.

The two-dimensional approach with this technique,

however, may provide limited information as to the

buccolingual position of the screw access opening.

While a three-dimensional radiographic imaging would

provide such information, such equipment is not read-

ily available in all dental clinics.

CONCLUSION

A simple and undemanding procedure for locating the

abutment screw access to allow abutment retrieval was

described using readily available information on the

implant system and the postcementation periapical

radiograph. The implant abutment radiographic image

was captured on a digital camera and the image was

manipulated using Word document software to esti-

mate the screw access location on the crown. This

technique can be performed by anyone with a com-

puter, without the need for special equipment or soft-

ware.

REFERENCES

1. Prestpino V, Ingber A, Kravitz J, Whitehead GM. A practical approach for

retrieving cement-retained, implant-supported restorations. Quintessence

Dent Technol 2001;24:182187.

2. Misch CE. Contemporary Implant Dentistry. St Louis: Mosby 1993:651685.

3. Schweitzer DM, Berg RW, Mancia GO. A technique for retrieval of cement-

retained implant-supported prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 2011;106:134138.

4. Pietrabissa R, Gionso L, Quaglini V, Di Martino E, Simion M. An in vitro study

on compensation of mismatch of screw versus cement-retained implant sup-

ported xed prostheses. Clin Oral Implants Res 2000;11:448457.

5. Wood MR, Vermilyea SG; Committee on research in xed prosthodontics of

the Academy of Fixed Prosthodontics. A review of selected dental literature

on evidence-based treatment planning for dental implants: report of the

Committee on research in xed prosthodontics of the Academy of Fixed Pros-

thodontics. J Prosthet Dent 2004;92:447462.

6. Taylor TD, Agar JR. Twenty years of progress in implant prosthodontics. J

Prosthet Dent 2002;88:8995.

7. Torrado E, Ercoli C, Al Mardini M, et al. A comparison of the porcelain fracture

resistance of screw-retained and cement-retained implant-supported metal-

ceramic crowns. J Prosthet Dent 2004;91:532537.

8. Hebel KS, Gajjar RC. Cement-retained versus screw-retained implant restor-

ations: achieving optimal occlusion and esthetics in implant dentistry. J

Prosthet Dent 1997;77:2835.

9. Breeding LC, Dixon DL, Bogacki MT, Tietge JD. Use of luting agents with an

implant system: part I. J Prosthet Dent 1992;68:737741.

10. Mehl C, Harder S, Wolfart M, Kern M, Wolfart S. Retrievability of implant-retained

crowns following cementation. Clin Oral Implants Res 2008;19:13041311.

11. Goodacre CJ, Bernal G, Rungcharassaeng K, Kan JY. Clinical complications

with implants and implant prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 2003;90:121132.

12. Schwedhelm ER, Raigrodski AJ. A technique for locating implant abutment

screws of posterior cement-retained metal-ceramic restorations with ceramic

occlusal surfaces. J Prosthet Dent 2006;95:165167.

13. Rajeev Gupta P, Verma R. A simple technique for removing cement retained

implant prosthesis in case of abutment screw loosening: a case report. Indian

J Dent Sci 2009;1:3841.

14. Doerr J. Simplied technique for retrieving cemented implant restorations. J

Prosthet Dent 2002;88:352353.

15. Figueras-Alvarez O, Cedeo R, Cano-Batalla J, Cabratosa-Termes J. A method

for registering the abutment screw position of cement-retained implant res-

torations. J Prosthet Dent 2010;104:6062.

16. Daher T, Morgano SM. The use of digital photographs to locate implant abut-

ment screws for implant-supported cement-retained restorations. J Prosthet

Dent 2008;100:238239.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- (Razavi) Design of Analog Cmos Integrated CircuitsDocument21 pages(Razavi) Design of Analog Cmos Integrated CircuitsNiveditha Nivi100% (1)

- Effective Time ManagementDocument61 pagesEffective Time ManagementTafadzwa94% (16)

- Multi-Unit Implant Impression Accuracy: A Review of The LiteratureDocument1 pageMulti-Unit Implant Impression Accuracy: A Review of The LiteratureUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Level and Determinants of Knowledge of Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis Among Railway Workers in MalaysiaDocument10 pagesLevel and Determinants of Knowledge of Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis Among Railway Workers in MalaysiaUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- StaphyloBase: A Specialized Genomic Resource For The Staphylococcal Research CommunityDocument9 pagesStaphyloBase: A Specialized Genomic Resource For The Staphylococcal Research CommunityUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Effect of Cassia Surattensis Burm. F., Flower Methanolic Extract On The Growth and Morphology of Aspergillus NigerDocument7 pagesEvaluation of The Effect of Cassia Surattensis Burm. F., Flower Methanolic Extract On The Growth and Morphology of Aspergillus NigerUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Growth Inhibitory Response and Ultrastructural Modification of Oral-Associated Candidal Reference Strains (ATCC) by Piper Betle L. ExtractDocument7 pagesGrowth Inhibitory Response and Ultrastructural Modification of Oral-Associated Candidal Reference Strains (ATCC) by Piper Betle L. ExtractUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Enhanced Post Crown Retention in Resin Composite-Reinforced, Compromised, Root-Filled Teeth: A Case ReportDocument6 pagesEnhanced Post Crown Retention in Resin Composite-Reinforced, Compromised, Root-Filled Teeth: A Case ReportUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Influence of Object Location in Different FOVs On Trabecular Bone Microstructure Measurements of Human MandibleDocument1 pageInfluence of Object Location in Different FOVs On Trabecular Bone Microstructure Measurements of Human MandibleUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Global Search For Right Cell Type As A Treatment Modality For Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument1 pageGlobal Search For Right Cell Type As A Treatment Modality For Cardiovascular DiseaseUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Genomic Reconnaissance of Clinical Isolates of Emerging Human Pathogen Mycobacterium Abscessus Reveals High Evolutionary PotentialDocument10 pagesGenomic Reconnaissance of Clinical Isolates of Emerging Human Pathogen Mycobacterium Abscessus Reveals High Evolutionary PotentialUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Reusable Heat-Sensitive Phantom For Precise Estimation of Thermal Profile in Hyperthermia ApplicationDocument2 pagesReusable Heat-Sensitive Phantom For Precise Estimation of Thermal Profile in Hyperthermia ApplicationUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Prosthetic Management of Mid-Facial Defect With Magnet-Retained Silicone ProsthesisDocument2 pagesProsthetic Management of Mid-Facial Defect With Magnet-Retained Silicone ProsthesisUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- University of Malaya Dental Students' Attitudes Towards Communication Skills Learning: Implications For Dental EducationDocument9 pagesUniversity of Malaya Dental Students' Attitudes Towards Communication Skills Learning: Implications For Dental EducationUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Patients' Level of Satisfaction With Cleft Treatment Using The Cleft Evaluation ProfileDocument12 pagesAssessment of Patients' Level of Satisfaction With Cleft Treatment Using The Cleft Evaluation ProfileUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Transient Loss of Power of Accommodation in 1 Eye Following Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block: Report of 2 CasesDocument5 pagesTransient Loss of Power of Accommodation in 1 Eye Following Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block: Report of 2 CasesUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Translating The Research Diagnostic Criteria For Temporomandibular Disorders Into Malay: Evaluation of Content and ProcessDocument0 pagesTranslating The Research Diagnostic Criteria For Temporomandibular Disorders Into Malay: Evaluation of Content and ProcessUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Tooth Size Discrepancies in An Orthodontic PopulationDocument7 pagesTooth Size Discrepancies in An Orthodontic PopulationUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Treatment of A Maxillary Dento-Alveolar Defect Using An Immediately Loaded Definitive Zygoma Implant-Retained Prosthesis With 11-Month Follow-Up: A Clinical ReportDocument5 pagesTreatment of A Maxillary Dento-Alveolar Defect Using An Immediately Loaded Definitive Zygoma Implant-Retained Prosthesis With 11-Month Follow-Up: A Clinical ReportUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences Research100% (1)

- The Safety Zone For Mini-Implant Maxillary Anchorage in MongoloidsDocument5 pagesThe Safety Zone For Mini-Implant Maxillary Anchorage in MongoloidsUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Psidium Guajava and Piper Betle Extracts On The Morphology of Dental Plaque BacteriaDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Psidium Guajava and Piper Betle Extracts On The Morphology of Dental Plaque BacteriaUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Stress and Its Relief Among Undergraduate Dental Students in MalaysiaDocument9 pagesStress and Its Relief Among Undergraduate Dental Students in MalaysiaJacky TangNo ratings yet

- The Antimicrobial Efficacy of Elaeis Guineensis: Characterization, in Vitro and in Vivo StudiesDocument18 pagesThe Antimicrobial Efficacy of Elaeis Guineensis: Characterization, in Vitro and in Vivo StudiesUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Scanning Electron Microscopic Study of Piper Betle L. Leaves Extract Effect Against Streptococcus Mutans ATCC 25175Document10 pagesScanning Electron Microscopic Study of Piper Betle L. Leaves Extract Effect Against Streptococcus Mutans ATCC 25175University Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Talon Cusp Affecting Primary Dentition in Two Siblings: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesTalon Cusp Affecting Primary Dentition in Two Siblings: A Case ReportUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Strawberry Gingivitis As The First Presenting Sign of Wegener's Granulomatosis: Report of A CaseDocument4 pagesStrawberry Gingivitis As The First Presenting Sign of Wegener's Granulomatosis: Report of A CaseUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Practices and Beliefs Among Malaysian Dentists and Periodontists Towards Smoking Cessation InterventionDocument7 pagesPractices and Beliefs Among Malaysian Dentists and Periodontists Towards Smoking Cessation InterventionUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Structured Student-Generated Videos For First-Year Students at A Dental School in MalaysiaDocument8 pagesStructured Student-Generated Videos For First-Year Students at A Dental School in MalaysiaUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Reliability of Voxel Gray Values in Cone Beam Computed Tomography For Preoperative Implant Planning AssessmentDocument1 pageReliability of Voxel Gray Values in Cone Beam Computed Tomography For Preoperative Implant Planning AssessmentUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Promoting Oral Cancer Awareness and Early Detection Using A Mass Media ApproachDocument8 pagesPromoting Oral Cancer Awareness and Early Detection Using A Mass Media ApproachUniversity Malaya's Dental Sciences ResearchNo ratings yet

- Canon imageFORMULA DR-X10CDocument208 pagesCanon imageFORMULA DR-X10CYury KobzarNo ratings yet

- PC3 The Sea PeopleDocument100 pagesPC3 The Sea PeoplePJ100% (4)

- Flexibility Personal ProjectDocument34 pagesFlexibility Personal Projectapi-267428952100% (1)

- 1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDDocument81 pages1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDJerome Samuel100% (1)

- Diia Specification: Dali Part 252 - Energy ReportingDocument15 pagesDiia Specification: Dali Part 252 - Energy Reportingtufta tuftaNo ratings yet

- 11bg USB AdapterDocument30 pages11bg USB AdapterruddyhackerNo ratings yet

- Lathe - Trainer ScriptDocument20 pagesLathe - Trainer ScriptGulane, Patrick Eufran G.No ratings yet

- Certificate Testing ResultsDocument1 pageCertificate Testing ResultsNisarg PandyaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Honda Bikes in CoimbatoreDocument43 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Honda Bikes in Coimbatorenkputhoor62% (13)

- Pitch Manual SpecializedDocument20 pagesPitch Manual SpecializedRoberto Gomez100% (1)

- Who will buy electric vehicles Segmenting the young Indian buyers using cluster analysisDocument12 pagesWho will buy electric vehicles Segmenting the young Indian buyers using cluster analysisbhasker sharmaNo ratings yet

- Chap 2 Debussy - LifejacketsDocument7 pagesChap 2 Debussy - LifejacketsMc LiviuNo ratings yet

- Metal Framing SystemDocument56 pagesMetal Framing SystemNal MénNo ratings yet

- Advanced Ultrasonic Flaw Detectors With Phased Array ImagingDocument16 pagesAdvanced Ultrasonic Flaw Detectors With Phased Array ImagingDebye101No ratings yet

- Daftar Spesifikasi Teknis Pembangunan Gedung Kantor BPN BojonegoroDocument6 pagesDaftar Spesifikasi Teknis Pembangunan Gedung Kantor BPN BojonegoroIrwin DarmansyahNo ratings yet

- ADDRESSABLE 51.HI 60854 G Contoller GuideDocument76 pagesADDRESSABLE 51.HI 60854 G Contoller Guidemohinfo88No ratings yet

- g4 - Stress Analysis of Operating Gas Pipeline Installed by HorizontalDocument144 pagesg4 - Stress Analysis of Operating Gas Pipeline Installed by HorizontalDevin DickenNo ratings yet

- Concept Page - Using Vagrant On Your Personal Computer - Holberton Intranet PDFDocument7 pagesConcept Page - Using Vagrant On Your Personal Computer - Holberton Intranet PDFJeffery James DoeNo ratings yet

- Motor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor ConnectionsDocument1 pageMotor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor Connectionsczds6594No ratings yet

- Introduction To Finite Element Methods (2001) (En) (489s)Document489 pagesIntroduction To Finite Element Methods (2001) (En) (489s)green77parkNo ratings yet

- The CongoDocument3 pagesThe CongoJoseph SuperableNo ratings yet

- 07.03.09 Chest Physiotherapy PDFDocument9 pages07.03.09 Chest Physiotherapy PDFRakesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Elements of ClimateDocument18 pagesElements of Climateእኔ እስጥፍNo ratings yet

- DNB Paper - IDocument7 pagesDNB Paper - Isushil chaudhari100% (7)

- Hyperbaric WeldingDocument17 pagesHyperbaric WeldingRam KasturiNo ratings yet

- O2 Orthodontic Lab Catalog PDFDocument20 pagesO2 Orthodontic Lab Catalog PDFplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Aacra Draft Preliminary Report PDFDocument385 pagesAacra Draft Preliminary Report PDFBeselam SeyedNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonic Weld Examination ProcedureDocument16 pagesUltrasonic Weld Examination ProcedureramalingamNo ratings yet