Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Amateur and The Expert

Uploaded by

benjaminschwarz0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

111 views4 pagesBenjamin Schwarz on intellectual journalism and international affairs

Original Title

Amateur and the Expert

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentBenjamin Schwarz on intellectual journalism and international affairs

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

111 views4 pagesAmateur and The Expert

Uploaded by

benjaminschwarzBenjamin Schwarz on intellectual journalism and international affairs

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

The " Amateur" and the " Expert": Intellectual Journalism and International Affairs

Review by: Benjamin Schwarz

World Policy Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Winter, 1997/1998), pp. 97-99

Published by: The MIT Press and the World Policy Institute

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40209559 .

Accessed: 01/06/2014 18:05

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Sage Publications, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Policy

Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 107.212.213.167 on Sun, 1 Jun 2014 18:05:53 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

B##KS

Benjamin

Schwarz is executive editor

of

the World

Policy Journal

and a senior

fellow

at the World

Policy

Institute.

The "Amateur" and the

"Expert"

Intellectual

Journalism

and International Affairs

Benjamin

Schwarz

In

1956,

cultural critic

Dwight

MacDonald

surveyed

the condition of American intellec-

tual

journalism

and did not like what he

saw.

Dismissing

the commercial

magazines

as a

wasteland,

he went on to

judge

The New

Republic

and The Nation as

"clinging

to the

platitudes

of liberal

orthodoxy...

shrunken,

drearily predictable

and of little interest to

most American intellectuals." Not

surpris-

ingly, given

his

loathing

of

anything

that

smacked of

"midcult,"

MacDonald devoted

his

strongest

criticism to what he called the

"middlebrow"

journals

that tried to

pass

as

intellectual

magazines

-

The

Atlantic,

Har-

per's,

and the now-extinct

Reporter

and Satur-

day

Review

-

which,

in

trying

to reach a

general

audience, consistently

underesti-

mated their readers'

intelligence,

and thus

produced pieces

that were at once

preten-

tious and

insipid.

To

MacDonald,

Britain had what the

United States needed.

Americans,

he ar-

gued,

write as

professionals,

either as schol-

ars concerned with advancement in the

academy

-

who

produce

the

jargon-riddled,

cautious,

and

overspecialized

articles of the

academic

journals

-

or as

journalists

con-

cerned with

attracting

a

large

and

profitable

audience

-

who write the

pandering

and

slick articles of the commercial

press.

In

contrast,

intellectual

journalism

in

Britain,

he

maintained,

was imbued with the

spirit

of amateurism. Intellectuals there were nei-

ther

writing

for academic

colleagues

who

they

had to

impress

(and

not

offend)

nor for

a

general readership

to whose lowest com-

mon denominator

they

had

constantly

to

appeal.

A

Narrowing

Field

With the

periodic mourning

of the

passing

of the

"public

intellectual,"

MacDonald's in-

dictment has become familiar

(although

he

was somewhat ahead of his

time,

since he

wrote his

survey

when that breed was still

supposed

to be

walking

the

earth).

Since the

time of MacDonald's

diatribes,

the

pressures

of academic

professionalism

on the one hand

and the

marketplace

on the other have be-

come far more

intense,

further

hemming

in

intellectual

journalism.

The New Yorker

may

or

may

not be

transforming

itself into

Vanity

Fair;

it is

clearly, however,

far less interested

than it was in

publishing lengthy, complex

essays.

Even those

objects

of MacDonald's

scorn,

The

Reporter

and

Saturday Review,

which were

at least outlets for some serious

writers, long

ago

became extinct in the Darwinian world

of

for-profit magazine publishing. Moreover,

a number of the more

widely

read

quarter-

lies

-

the Yale and Antioch reviews and the

South Atlantic

Quarterly,

for instance

-

that

once

published essays

on

biographical,

his-

torical, political,

social,

and economic

topics

have become

exclusively literary publica-

tions,

and more

academically

oriented.

In at least one

way, though,

the situation

has

improved

since MacDonald's

essay.

The

Atlantic and

Harper's,

which,

for

peculiar

rea-

sons,

have been less

subject

to market

pres-

sures, long ago

shed their middlebrow

earnestness.

(Today,

the Wilson

Quarterly,

de-

scribed

by

the

leading

historian of American

publishing

as an

"upper-middlebrow

Reader's

Digest,"

is similar to what those

magazines

were in the

1950s.)

Within broad limits

The "Amateur" and the

"Expert"

97

This content downloaded from 107.212.213.167 on Sun, 1 Jun 2014 18:05:53 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

they

are

quite open

to

ground-breaking, pro-

vocative,

and "difficult" articles.

But the

primary purpose

of The Atlantic

and

Harper's

is not to serve as a forum for

original thinkers; rather,

it is to

report

exist-

ing

trends

-

to

serve,

as

Harper's

editor Lewis

Lapham says,

as "a

monthly

review of the

trend of events and the tendencies of the

public

mind." Still less is this the function of

the

opinion

weeklies. MacDonald bemoaned

the absence of an American New Statesmen or

Spectator,

but for all their

verve,

the contents

of these

journals was,

and

is,

pretty

thin.

Two thousand

words,

the

upper

limit for

the

length

of most articles

in,

say,

The Nation

or The New

Republic,

is

just enough

to

express

a

point

of view on some

topical subject;

it is

not

enough

to

present

and

argue

an unortho-

dox idea. At their

best,

such

pieces

can be

provocative,

but that

length

often seems to

encourage

a snide and

glib style

and articles

that

are,

perforce,

little more than extended

opinion pieces.

This

type

of article

hardly

advances intellectual life.

The American Tradition

Rather than extol the mid-twentieth-cen-

tury

British

weeklies,

MacDonald should

have

championed

the British intellectual

quarterlies

of the nineteenth

century,

the Ed-

inburgh

and Westminster

reviews,

which

pub-

lished

long, well-written,

and

widely

read

theoretical and

practical essays.

In

fact,

the

United States need not look across the Atlan-

tic for models because America had a tradi-

tion of intellectual

journalism

as

impressive

as

Britain's, dating

from the nineteenth cen-

tury's Atlantic, Harper's,

The

Century,

and

North American Review and

flourishing

well

into the twentieth

century.

As Lewis Mum-

ford remembered

nostalgically:

"Until the

Great

Depression

there was a

sufficiently

wide

variety

of weeklies and

monthlies,

some like The Dial and The American Mer-

cury paying

a modest two cents a

word,

some like

Harper's

and Scribner's

paying

more,

so that I never was

compelled

to un-

dertake a

project

that did

not,

in some

way,

further

my purposes....

It would seem almost

sadistic to

give

the

present generation

of

writers an account of the liberated state of

publishing

then." MacDonald could have

looked back at a

time,

before he started writ-

ing,

when a far

greater

number of

magazines

published lively, serious,

and

well-developed

articles for an

intelligent general

audience,

for in addition to

Scribner's,

The

Dial,

and

The American

Mercury,

The

Century,

The Out-

look,

The World's

Work,

The

Forum,

The

Masses,

and Review

of

Reviews had

long

since

passed

from the scene.

Even when MacDonald was

writing,

The

New Yorker and the more

general quarterlies

such as the

Yale, Antioch,

South

Atlantic,

Par-

tisan,

and

Virginia Quarterly

reviews contin-

ued to

publish long,

ambitious,

nonacademic

pieces.

While these intellectual

quarterlies

always paid

little and had small

circulations,

they

mattered. In the

1930s,

Yale Review

published John Maynard Keynes's

literate,

accessible,

and heterodox

essays

on the world

economy.

In the

1940s,

Antioch Review

pub-

lished

Carey

McWilliams's and

Ralph

El-

lison's

pioneering essays

on race in America.

In the

1950s,

I am

told,

there were

young

account executives and

lawyers

in New York

who

eagerly

awaited the next

Kenyon

Review.

Virginia Quarterly

Review

-

which continues

to offer

fiction, poetry,

and

literary

criticism

as well as social criticism and

essays

on

poli-

tics and even economics

-

played

a

promi-

nent role in the

country's

intellectual and

cultural life.

Indeed,

from

Henry

Adams,

Frederick

Jackson

Turner,

and Mark Twain to Waldo

Frank, Mumford, Randolph

Bourne,

H. L.

Mencken,

Edmund

Wilson,

C.

Wright

Mills,

and C. Vann

Woodward,

American

intellectual

journalism's highest

achieve-

ment

was,

and

remains,

the

lively yet

seri-

ous

essay

written with

lucidity, style,

and

what Allen Tate called "leisured

thought"

and "considered

depth."

(To

appreciate

these

last

characteristics, compare Henry

Adams's

annual reviews of

politics,

"The

Session,"

published

in the North American

Review,

98 WORLD POLICY

JOURNAL

This content downloaded from 107.212.213.167 on Sun, 1 Jun 2014 18:05:53 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

which

brought

events in

Washington

into

the

perspectives

of

history

and

philosophical

statesmanship,

to,

say,

The New Yorkers

"Letter from

Washington,"

which has be-

come

merely high-level Washington gossip.)

These

pieces, dealing

with

history, poli-

tics, foreign affairs,

and cultural criticism

display

a

depth

of

knowledge

and an infor-

mal and

personal style

that

emerges

when

the writer is

trying

neither to

appease

nor

impress

the

reader,

but

regards

him or her as

an intellectual

equal.

For this kind of writ-

ing

to

thrive,

the writer must

recognize

the

reader to be "the cultivated

layman

who felt

...that the

high places

of literature were not

beyond

his reach: he saw himself and the

author in a communion of

understanding

in

which the communicants were

necessary

to

each

other,"

as Tate described the ideal.

This tradition is almost

entirely

dead.

Only

The American

Scholar, Virginia Quarterly

Review,

The

Atlantic,

and

Harper's

occasional-

ly

offer such

pieces.

And,

with the

exception

of those in The Atlantic and

Harper's, hardly

anyone

reads them. In

fact,

it is often

impos-

sible to find the former

journals

in even the

most

highbrow

bookstores or newsstands.

The

Myopia of

the

Expert

This dearth of outlets for serious and sus-

tained

essays

on culture and

public

affairs

has had a

particularly unhappy

effect on the

intellectual discourse

concerning foreign pol-

icy.

The

"public

intellectuals" of the

past,

by

definition,

wrote and commented

upon

subjects

with which

they

were not

profes-

sionally

involved

-

Mumford on architec-

ture,

Woodward on America's

self-righteous

approach

to the

world,

and Edmund Wilson

on the Dead Sea Scrolls and on the literature

of the Civil

War,

for instance.

Jane Jacobs

could write in a

startling

new

way

about cit-

ies

precisely

because she was not

trapped

in

the orthodoxies of the urban

planning pro-

fessionals; ideally, public

intellectuals

bring

to their

subject

of

inquiry

a breadth of

knowledge

and

imagination unhampered by

"professionalization.

"

Today, however,

discussion of

foreign

af-

fairs is left to the

professionals. Harper's

al-

most never and The Atlantic

only rarely

publish pieces

on

foreign affairs,

believing

that the

foreign policy periodicals

-

Foreign

Affairs, Foreign Policy,

The National

Interest,

and the World

Policy Journal

-

cover that

beat. But this is like

neglecting pieces

on

crime or race because those

topics

are ad-

dressed in the American

Journal of Sociology,

The

foreign policy magazines

are

really

professional journals;

their contributors

(and,

to a lesser

degree,

their

readership)

are

drawn

by

and

large

from the

"policy

com-

munity"-

-current and former

government

officials and the academics and think tank

analysts.

As these contributors recirculate

the same views and

"debates,"

more often

than not a stale consensus tends to take hold.

Now that

foreign policy

has become the

exclusive

province

of the

experts,

on the rare

occasion that the

general

intellectual

maga-

zines choose to run a

piece

on

foreign policy,

they simply

round

up

the usual

suspects.

During

the Vietnam

War,

when the New

York Review

of

Books was in its "radical"

phase,

it

published

articles on American

pol-

icy by

Gore

Vidal; now,

it turns to

Stanley

Hoffmann

(as

does

Dissent)

and to former

State

Department

officials.

Thus,

when the educated

public

seeks in-

tellectual discussion of

foreign policy

-

dis-

cussion of America's

place

in the

world,

and

an

attempt

to

put

that

conception

in broader

philosophical, cultural,

or historical contexts

-

by

writers whose horizons extend

beyond

Foggy

Bottom and the Council on

Foreign

Relations,

it

really

has nowhere to turn. At

a time

when,

as we are

constantly reminded,

the United States must reexamine funda-

mentally

its role in the world and when

American

society

faces

global pressures

that

it is less and less able to

manage,

let alone

control,

American intellectual

journalism

should revive its tradition of amateurism and

"considered

depth."

It could stand fewer

pol-

icy experts,

but it needs its

Adamses,

Twains, Wilsons,

and Woodwards.*

The "Amateur" and the

"Expert"

99

This content downloaded from 107.212.213.167 on Sun, 1 Jun 2014 18:05:53 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Bowling Alone: Revised and Updated: The Collapse and Revival of American CommunityFrom EverandBowling Alone: Revised and Updated: The Collapse and Revival of American CommunityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (296)

- KeirSey Score SheetDocument1 pageKeirSey Score Sheetpratik9No ratings yet

- Peterson - Magazines 20th CenturyDocument480 pagesPeterson - Magazines 20th CenturyhehrlicherNo ratings yet

- Tony MacAlpine - Autumn LordsDocument11 pagesTony MacAlpine - Autumn LordsJules MartzNo ratings yet

- Difference Between A Press Release and A Press ReportDocument1 pageDifference Between A Press Release and A Press ReportPitamber Rohtan67% (3)

- To Lead the Free World: American Nationalism and the Cultural Roots of the Cold WarFrom EverandTo Lead the Free World: American Nationalism and the Cultural Roots of the Cold WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Talents and Technicians - John AldridgeDocument161 pagesTalents and Technicians - John AldridgeVernon SullivanNo ratings yet

- Accounting for Capitalism: The World the Clerk MadeFrom EverandAccounting for Capitalism: The World the Clerk MadeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Author in Chief: The Untold Story of Our Presidents and the Books They WroteFrom EverandAuthor in Chief: The Untold Story of Our Presidents and the Books They WroteRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Wall Streeters: The Creators and Corruptors of American FinanceFrom EverandWall Streeters: The Creators and Corruptors of American FinanceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- MM - June 2016Document72 pagesMM - June 2016Dennis ShongiNo ratings yet

- Architectural Digest Mexico - 02 2019Document147 pagesArchitectural Digest Mexico - 02 2019Anonymous v2MqAXI100% (3)

- Roggenkamp - Narrating The News New Journalism and Literary Genre in Late Nineteenth-Century American Newspapers and FictionDocument220 pagesRoggenkamp - Narrating The News New Journalism and Literary Genre in Late Nineteenth-Century American Newspapers and FictionMartínNo ratings yet

- Critical Americans: Victorian Intellectuals and Transatlantic Liberal ReformFrom EverandCritical Americans: Victorian Intellectuals and Transatlantic Liberal ReformNo ratings yet

- Moderates: The Vital Center of American Politics, from the Founding to TodayFrom EverandModerates: The Vital Center of American Politics, from the Founding to TodayRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Patriotism Is Not Enough: Harry Jaffa, Walter Berns, and the Arguments that Redefined American ConservatismFrom EverandPatriotism Is Not Enough: Harry Jaffa, Walter Berns, and the Arguments that Redefined American ConservatismNo ratings yet

- Free People, Free Markets: How the Wall Street Journal Opinion Pages Shaped AmericaFrom EverandFree People, Free Markets: How the Wall Street Journal Opinion Pages Shaped AmericaNo ratings yet

- Popularizing the Past: Historians, Publishers, and Readers in Postwar AmericaFrom EverandPopularizing the Past: Historians, Publishers, and Readers in Postwar AmericaNo ratings yet

- NATO ExpansionDocument8 pagesNATO ExpansionbenjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Newspapers AxisDocument433 pagesNewspapers AxisMaks imilijan100% (1)

- Self-Exposure: Human-Interest Journalism and the Emergence of Celebrity in America, 1890-1940From EverandSelf-Exposure: Human-Interest Journalism and the Emergence of Celebrity in America, 1890-1940No ratings yet

- Action Plan in Campus JournalismDocument4 pagesAction Plan in Campus JournalismThelma Ruiz SacsacNo ratings yet

- Classic Detective Stories SummaryDocument51 pagesClassic Detective Stories SummaryVelmira Dimova IvanovaNo ratings yet

- Upper Case Lower CaseDocument84 pagesUpper Case Lower CaseaBlaqSerifNo ratings yet

- How To Write Special Feature Articles by Willard Grosvenor BleyerFrom EverandHow To Write Special Feature Articles by Willard Grosvenor BleyerNo ratings yet

- Citizen Reporters: S.S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine That Rewrote AmericaFrom EverandCitizen Reporters: S.S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine That Rewrote AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Cultural Cold War: ReviewsDocument5 pagesCultural Cold War: ReviewsAhmet KaplanNo ratings yet

- The Idea of the Journalistic Report in Late 19th Century AmericaDocument30 pagesThe Idea of the Journalistic Report in Late 19th Century AmericaBTKGORDONo ratings yet

- Jonathan Auerbach - Male Call - Becoming Jack London PDFDocument303 pagesJonathan Auerbach - Male Call - Becoming Jack London PDFligiaNo ratings yet

- R. McParland - Books & Readings (2011)Document3 pagesR. McParland - Books & Readings (2011)xadarshjhaNo ratings yet

- Voices of Revolution: The Dissident Press in AmericaFrom EverandVoices of Revolution: The Dissident Press in AmericaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Novels, Readers, and Reviewers: Responses to Fiction in Antebellum AmericaFrom EverandNovels, Readers, and Reviewers: Responses to Fiction in Antebellum AmericaNo ratings yet

- Ways of Writing: The Practice and Politics of Text-Making in Seventeenth-Century New EnglandFrom EverandWays of Writing: The Practice and Politics of Text-Making in Seventeenth-Century New EnglandNo ratings yet

- Writings in the United Amateur, 1915-1922From EverandWritings in the United Amateur, 1915-1922No ratings yet

- "A Thousand Little Things" The Dangers of Seriality in The Spectator and Moll Flanders - Lee KahanDocument20 pages"A Thousand Little Things" The Dangers of Seriality in The Spectator and Moll Flanders - Lee KahanfaktesNo ratings yet

- Foundations of Political Economy: Some Early Tudor Views on State and SocietyFrom EverandFoundations of Political Economy: Some Early Tudor Views on State and SocietyNo ratings yet

- Literature and Insurgency (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Ten Studies in Racial EvolutionFrom EverandLiterature and Insurgency (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Ten Studies in Racial EvolutionNo ratings yet

- Republic of Detours: How the New Deal Paid Broke Writers to Rediscover AmericaFrom EverandRepublic of Detours: How the New Deal Paid Broke Writers to Rediscover AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Lepore New Economy of LetterDocument3 pagesLepore New Economy of LetternanadadaNo ratings yet

- Just the Facts: How "Objectivity" Came to Define American JournalismFrom EverandJust the Facts: How "Objectivity" Came to Define American JournalismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- The Intellectual Versus The City: From Thomas Jefferson To Frank Lloyd WrightFrom EverandThe Intellectual Versus The City: From Thomas Jefferson To Frank Lloyd WrightNo ratings yet

- Reitz DetectingDocument55 pagesReitz DetectingMatea GrgurinovicNo ratings yet

- GRAFTON, A. The History of Ideas - Precept and PracticeDocument32 pagesGRAFTON, A. The History of Ideas - Precept and PracticeVanessa CarnieloNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurs of Ideology: Neoconservative Publishers in Germany, 1890-1933From EverandEntrepreneurs of Ideology: Neoconservative Publishers in Germany, 1890-1933No ratings yet

- Roberts-Firing The CanonDocument14 pagesRoberts-Firing The CanongiselleingridNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis American LiteratureDocument8 pagesPHD Thesis American Literaturekellylindemannmadison100% (2)

- Big Fiction How Conglomeration Changed The Publishing Industry and American Literature (Dan Sinykin) (Z-Library)Document328 pagesBig Fiction How Conglomeration Changed The Publishing Industry and American Literature (Dan Sinykin) (Z-Library)anónimo anónimoNo ratings yet

- Dubious Anniversary: Kosovo One Year Later, Cato Policy Analysis No. 373Document14 pagesDubious Anniversary: Kosovo One Year Later, Cato Policy Analysis No. 373Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Doomed16062014Document1 pageCapitalism Doomed16062014benjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Judge Ginsburg16062014Document1 pageJudge Ginsburg16062014benjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Of Course We Knew16062014Document1 pageOf Course We Knew16062014benjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- AMerican Inequality17062014Document2 pagesAMerican Inequality17062014benjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Loser17062014Document3 pagesRenaissance Loser17062014benjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Angry White Rural Men17062014Document3 pagesAngry White Rural Men17062014benjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- NATO at The CrossroadsDocument6 pagesNATO at The CrossroadsbenjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Exporting The Myth of A Liberal AmericaDocument10 pagesExporting The Myth of A Liberal AmericabenjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Strategic IndependenceDocument148 pagesStrategic IndependencebenjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- The Long and The Short of ItDocument8 pagesThe Long and The Short of ItbenjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Wiley Royal Institute of International AffairsDocument2 pagesWiley Royal Institute of International AffairsbenjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- The Vision ThingDocument22 pagesThe Vision ThingbenjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- Faley Memo of LawDocument43 pagesFaley Memo of LawbenjaminschwarzNo ratings yet

- GQ USA The 2023 Men of The Year IssueDocument178 pagesGQ USA The 2023 Men of The Year IssueGermán CubillosNo ratings yet

- GCF and LCM Word ProblemsDocument2 pagesGCF and LCM Word Problemsallan_apduaNo ratings yet

- Daily News Montreal 18 February 2009Document60 pagesDaily News Montreal 18 February 2009dailynewsmontreal100% (8)

- SMC Dance Concert ReportDocument2 pagesSMC Dance Concert ReportRicardoNazal100% (1)

- Liaquat 150TPD Finished Kraft QuotationDocument39 pagesLiaquat 150TPD Finished Kraft QuotationloveboydkNo ratings yet

- ATHF FiascoDocument5 pagesATHF FiascoJames John-EdwardNo ratings yet

- Template Yuridika (En)Document3 pagesTemplate Yuridika (En)SuwartonoYogyakartaNo ratings yet

- Gem News InternationalDocument16 pagesGem News Internationaljoniman9No ratings yet

- Barriers in CommunicationDocument21 pagesBarriers in CommunicationObaid ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- FFF EULA License Ver2.1 PDFDocument2 pagesFFF EULA License Ver2.1 PDFdododudux didoNo ratings yet

- Evaluating WebsitesDocument15 pagesEvaluating Websitesapi-298063936No ratings yet

- Thi thử tốt nghiệp THPT Quốc Gia 2024 - Liên trường THPT Huyện Cẩm Xuyên Hà TĩnhDocument6 pagesThi thử tốt nghiệp THPT Quốc Gia 2024 - Liên trường THPT Huyện Cẩm Xuyên Hà TĩnhdieplammacNo ratings yet

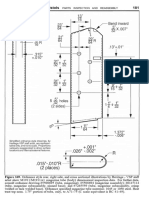

- The U.S. M1911 M1911A1 Pistols and Commercial M1911 Type Pistols - A Shop Manual (PDFDrive) - Unlocked-13Document15 pagesThe U.S. M1911 M1911A1 Pistols and Commercial M1911 Type Pistols - A Shop Manual (PDFDrive) - Unlocked-13Violeta Sosa rosarioNo ratings yet

- Joe Azaria and MidnightDocument3 pagesJoe Azaria and MidnightTommy BakerNo ratings yet

- Depeche Mode Are An English Electronic Music Band Which Formed in 1980, in BasildonDocument2 pagesDepeche Mode Are An English Electronic Music Band Which Formed in 1980, in BasildonndjokbestNo ratings yet

- Man Involved in Standoff Not Criminally Responsible: Sounds of The SeasonDocument16 pagesMan Involved in Standoff Not Criminally Responsible: Sounds of The SeasonAnonymous KMKk9Msn5No ratings yet

- "One Letter at A Time: Nancy Nicholson Joline," by Marilynn HuretDocument4 pages"One Letter at A Time: Nancy Nicholson Joline," by Marilynn HuretpspuzzlesNo ratings yet

- Crossword PuzzleDocument3 pagesCrossword PuzzleMarizCaniculaCimanesNo ratings yet

- EIHC Vol 7Document306 pagesEIHC Vol 7gibson150100% (1)

- APA For Students - Wilmington University College of Arts and SciencesDocument15 pagesAPA For Students - Wilmington University College of Arts and SciencesWilmington University - College of Arts and Sciences0% (1)

- Extemp Speech StructureDocument2 pagesExtemp Speech StructureChristine Megan Young0% (1)

- Weretiger (Human Lycanthrope) Fighter 2Document1 pageWeretiger (Human Lycanthrope) Fighter 2Xan CamposNo ratings yet