Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Poblome Bes WilletArchaeologicalResidueNetworks

Uploaded by

zamindarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Poblome Bes WilletArchaeologicalResidueNetworks

Uploaded by

zamindarCopyright:

Available Formats

Thoughts on the archaeological residue of

networks. A view from the East

Jeroen Poblome, Philip Bes & Rinse Willet

INTRODUCTION

O

ur paper is not focused on ancient Portus, connections between the eastern Mediterranean and

the Roman motherland, or even ports in the Roman East for that matter, but its general approach

hopefully may contribute to developing rational frameworks for approaching the issue of networks

from the perspective of Roman archaeologists. The empirical background to this paper is provided

by the ICRATES platform. ICRATES (Inventory of Crafts and Trade in the Roman East) was initiated

in 2004 and aims at (1) collecting published evidence for the output of artisans and for exchange in the

Roman East in an extensive database; (2) calibrating these data with original eldwork in the ancient

regions of Boeotia, Pisidia and Cilicia; and (3) developing innovative syntheses of the socio-cultural

impact and socio-economic positioning of craft activities in antiquity (Bes 2007; Bes and Poblome

2006; Bes and Poblome 2008; Bes and Poblome 2009).

It is common knowledge that the best inventions are conceived out of mild to extreme frustration

with the current state of affairs, and matters were no different with ICRATES. As ceramologists

working in an interdisciplinary research project in Turkey, we found it increasingly difcult to

answer the new questions posed by colleagues in other disciplines. All we had were the typo-

chronological responses provided by the traditional Roman ceramological toolbox. At the same

time, however, we are very much aware that this same tradition has made a major contribution to

our current understanding of ceramics and trade in the Roman East. ICRATES therefore consciously

links this rich tradition with new avenues of research, mostly in an attempt to introduce concepts of

material culture studies into the domain of Roman archaeology.

One of the most attractive aspects of the world of material culture studies is that nothing is simple

and straightforward any more, and, what is more, that it feels better that way. As a result, when

studying networks in the past we should start from questioning the obvious. In the online Oxford

English Dictionary (http://www.oed.com/) a network is dened as follows:

A chain or system of interconnected immaterial things, Any netlike or complex system or collection of

interrelated things, as topographical features, lines of transportation, or telecommunications routes (esp.

telephone lines), An interconnected group or chain of retailers, businesses, or other organizations and

An interconnected group of people; an organization; spec. a group of people having certain connections

(freq. as a result of attending a particular school or university) which may be exploited to gain preferment,

information, etc., esp. for professional advantage.

Clearly, the levels of analysis are dened by the system itself, its component elements (from

features to information and real people) and/or its underlying raison(s) detre and purpose(s).

Research into networks can make use of network analysis, which represents a collective set of

methodological tools developed with the aim of detecting and interpreting patterns of relationships

between the specic features (Brughmans 2010).

1

Networks can be studied also without recourse

to network analysis, however, and the current paper serves as an example of this more descriptive

and qualitative approach. Methodologically, it builds on the historical analytical concept of

connectivity as argued by Horden and Purcell (2000: 123): By this term, we understand the various

ways in which microregions cohere, both internally and also one with another in aggregates that

may range in size from small clusters to something

approaching the entire Mediterranean. In particular

we aim to apply the concept of connectivity in order

to provide historical meaning to recently collected

sets of archaeological data in much the same way as

was done recently in the eld of ancient history

(Malkin, Constantakopoulou and Panagopoulou

2009). This might seem to be a very light way of

approaching the functions of networks in the ancient

world, but the available archaeological data are not of

a sufcient quality to allow us to use anything more

than the descriptive methodologies of network analysis.

Archaeological data are, by denition, mute and in

need of well-dened metadata before they can be

used in computer-based approaches to network analy-

sis. When such metadata are not available, as is the

case with most traditional ceramic data that was not

collected with network analysis in mind, there is a

risk that the patterns produced will lead to circular

reasoning. While one technique might work, it would

not add any explanatory meaning to the archaeological

data. Consequently our paper is not just what one might

term as old wine in new bottles; it is instead an

attempt to illustrate how in some specic cases,

bridges can be built between data collected in the

traditional manner by Roman archaeologists and

descriptive analytical frameworks, such as connectivity,

and how meaning can be found in their patterning.

Apart from dening the analytical platform and

method, we also need to consider the broader context

of the data, in this case the Roman East. Recently,

Reger (2007; Elton and Reger 2007) has warned us

against the simplistic, over-geographical usage of the

concept of regions, and, considering that this paper is

built on the concept of connectivity between (micro)

regions, we should heed his words. Even ancient

authors agree on the difculty of dening regions in

antiquity, and they were in a position to know. There-

fore ICRATES considers regions more as radii of

action, with a potentially different size depending on

the kind of archaeological data under discussion, the

factor of agency in the past and/or the thematic

approach of the research. The eastern Mediterranean

was and still is complex from cultural, political, mili-

tary, religious, ethnological and linguistic points of

view, and its constituent regions therefore cannot be

expected to be uniform in denition or function.

The participants of the ICRATES project are

convinced that a focus on artisanal production is a

useful approach in this respect. Previously we have

argued that the symbiosis between a prosperous and

productive countryside and a busy town connected to

the wider world is to be regarded as the condicio sine

qua non for providing a sustainable basis for the devel-

opment of craft production and ensuring the presence of

its produce on long-distance markets (Poblome 2006).

When looking for connectivity, we can also approach

matters the other way round: from crafts to regions,

whilst making sure to avoid looking at only one

product, and concentrating on regional portfolios.

Modelling regional artisanal production should help

develop our understanding of the strengths and weak-

nesses of certain kinds of material produced. We

should also focus less on lines of production, but

much more on how these were integrated into the

economy of a region.

CASE-STUDIES

BOEOTIA

The region of Boeotia, representing one of the three

regions in which ICRATES is involved in eldwork,

provides a rst and clear example of the role of

networks in the eld of production from the perspective

of descriptive analysis. As with Rome and Portus in the

early Empire, the establishment of Constantinople

started to provide a new and clear focus in the eastern

Mediterranean from the fourth century AD onwards.

The place in Boeotia where we feel this effect most

clearly is the ancient town of Tanagra and its territory.

Within most sectors of the ancient town, as well as on

several of the rural sites in its territory, a striking pro-

portion of the ceramic assemblage consisted of Late

Roman 2 amphora fragments (Poblome, Ceulemans

and De Craen 2008: 568) (Table 21.1), for the most

part represented by one main fabric range. In our

view, the quantities of these oil amphorae, the fact

that other products such as jugs, lekanai and beehives

were made in the same fabric range, and the general

compatibility of the fabric with the regional clay raw

materials and geology, are strong indicators that a

series of Late Roman 2 amphorae was manufactured

in this study area. Partial conrmation of this hypoth-

esis came from recent Greek excavations at ancient

Delion, the port of Tanagra, where the remains of at

least one Late Roman 2 amphora workshop with a

kiln were excavated (as yet unpublished). So far, no

archaeometrical analysis has been performed in order

to conrm this further or establish possible links with

the material found at Tanagra. However, as a prelimi-

nary working hypothesis, we expect other production

394 POBLOME, BES & WILLET

sites to be found within the facies geographique of

Tanagra, not least because of their similarity to the

organization of other more widely distributed amphora

types (Bonifay 2004: 944).

The ancient authors tell us that the region of Tanagra

was involved in the production of wine and probably

also olive (oil?).

2

As regards networks, it reacted to

direct or indirect stimuli provided by the central

Roman authorities in the late Imperial period, in order

to supply olive oil to newly-established Constantinople

and/or Roman troops along the Danube (Karagiorgou

2001). At least some of the landholders in the region

of Tanagra were well placed to respond to these

needs and convert their agricultural products, or at

least to produce them more intensively. The resultant

well-being this brought for the community at Tanagra

is epitomized by the ranges of imported table- and

cooking-wares and amphorae (Table 21.2). In this

way, we see the emergence of a uid pattern of

exchange in response to the demands of empire at the

supra-regional level.

It is interesting to note that the results of our pre-

liminary comparisons between Tanagra and two other

contemporary Boeotian towns, Thespiae and Koroneia,

do not indicate similar types and proportions of

imported pottery: furthermore, in the case of Koroneia

Late Roman 2 amphorae played a relatively minor role

(Table 21.3). We consider this to be an important

observation that warns us against making excessively

generalized regional conclusions. The presence of

amphorae shows that networks can function, as was

the case with Boeotian Tanagra. At the same time,

however, the fact that they could also be absent at

sites c. 30 km distant with different material culture

assemblages, hints at limits to supply networks.

SAGALASSOS

The workings of networks can be more subtle, how-

ever. In the case of ancient Sagalassos, the Pisidian

town at which members of the ICRATES project also

undertake ceramological analysis, no amphorae seem

to have been produced at or near the site before the

middle of the fourth century AD. At some point in the

third quarter of that century, however, one or more

landholders in the territory of Sagalassos decided to

start packaging part of their agricultural produce in

amphorae (Poblome et al. 2008).

Amphorae usually were produced in regions that

disposed of a marketable agricultural surplus destined

for wide distribution. In the case of Sagalassos, they

were not widely produced since the town is located

within the Taurus mountain range and is relatively

distant from the Mediterranean or navigable rivers

the ideal environments for the production of amphorae.

Thus the fact that amphorae were manufactured in a

Pisidian context at all is something that needs to be

explained. In our opinion, the landholders who took

the initiative to produce local amphorae were faced

with a sequence of conscious decisions while posses-

sing sufcient capital to be able to initiate and maintain

their production. We have suggested previously that

they would have chosen to produce the containers

only with specic aims in mind, possibly in response

to changing conditions in either the generation of

their agricultural produce (supply) or the level of

interest in their produce (demand), or perhaps both.

In this respect, the fact that amphorae were chosen at

all as containers for their surplus production is impor-

tant in that this is a functional category of pottery that

traditionally was conceived for distribution, and the

TABLE 21.1. The absolute and relative quantities of Late Roman 2 amphorae, other late Roman amphorae and late Roman red

slip wares for urban Tanagra and four rural sites.

URBAN

(no. 13,464)

TS2

(no. 1,158)

TS3

(no. 4,848)

TS4

(no. 1,626)

% of sherds assigned to the late

Roman period

31.21 (no. 4,202) 8.89 (no. 103) 10.46 (no. 507) 10.09 (no. 164)

% of Late Roman 2 fragments (of

the late Roman total)

34.91 (no. 1,467) 29.13 (no. 30) 16.17 (no. 82) 26.22 (no. 43)

% of all other late Roman

amphorae sherds (of the late

Roman total)

39.79 (no. 1,672) 41.75 (no. 43) 43.20 (no. 219) 59.15 (no. 97)

% of late Roman red slip ware

sherds (of the late Roman total)

4.66 (no. 196) 7.89 (no. 40) 4.88 (no. 8)

THOUGHTS ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESIDUE OF NETWORKS 395

landholders must have been aware of this. Thus the late

Roman amphorae from the region of Sagalassos could

represent tentative evidence for the rationalization of

parts of the agricultural matrix of the study area,

possibly coupled to an intensication of production.

Furthermore, the typological resemblance of the early

series of Sagalassos amphorae to the initial phase of

Late Roman 1 wine amphorae suggests that they were

cultivating vines. We consider it to be more than a

coincidence that the same period saw the beginning

of the production of typical relief decorated oinophoroi

in the potters quarter in the eastern suburb of

TABLE 21.2. The range of functionalities for local/regional, imported and uncertain fabrics for Tanagra. (Updated from Poblome,

Ceulemans and De Craen 2008: 567, table 4.)

Food consumption

Local/regional production Imported Uncertain

Tanagra/Boeotian fabric(s): plain-wares African and Phocaean red

slip wares

Red slip, table-wares

Food processing & preparation

Local/regional production Imported Uncertain

Buff fabric: plain-wares Aegean: casseroles or

amphorae

Black Sea fabric?: amphorae

and plain-wares

Casserole fabrics: casseroles Late Roman 2: plain-wares Grog fabric, plain-wares

Orange micaceous: plain-wares

Orange sandy: plain-wares

Tanagra/Boeotian fabric(s): plain-wares

White-grey clayey fabric: plain-wares

Agricultural production

Local/regional production Imported Uncertain

Brown sandy: amphorae Black Sea fabric: amphorae Red slip: amphorae

Buff fabric: amphorae Late Roman 1: amphorae

Casserole fabric(s): amphorae and beehives Late Roman 2: amphorae,

(amphorae) stands and

beehives

Orange micaceous: amphorae Late Roman 3: amphorae

Orange sandy: amphorae and beehives Late Roman 4: amphorae

Tanagra/Boeotian fabric(s): amphorae and beehives Late Roman 5: amphorae

White-grey clayey fabric: amphorae

TABLE 21.3. The absolute and relative quantities of late Roman pottery and Late Roman 2 amphorae at Koroneia (not yet fully

studied) and Thespiae.

Koroneia Thespiae

Total 10,443 Total 8,701

% late Roman of total 3.31% (no. 346) % late Roman of total 4.90% (no. 408)

% Late Roman 2 of late Roman total 16.18% (no. 56) % Late Roman 2 of late Roman total 39.22% (no. 160)

396 POBLOME, BES & WILLET

Sagalassos (Talloen and Poblome 2005; Murphy and

Poblome 2011).

Once again, the emergence of Constantinople as the

major pole of attraction or node in network terms

within the context of broader regional connections in

the Roman East, and the contingent civil and military

opportunities that it offered, may have tempted some

landholders in the area of Sagalassos to specialize

and intensify part of their agricultural production. The

not so straightforward results of the residue analysis

performed on the Sagalassos amphorae, albeit based

on an early Byzantine sample series (Romanus et al.

2009), as well as the fact that so far we have not been

able to characterize the distribution pattern of these

amphorae, suggest that we shall probably never under-

stand the economic calculations made by the ancient

landowners. Nevertheless, we should like to suggest

that they took networking into account in order to

ensure that their produce circulated.

A major challenge that hinders our understanding of

how connectivity worked in the Roman East is the fact

that our picture is still very incomplete. There are still,

for example, many hidden landscapes of production.

Thus, when working at Tanagra, Thespiae and Koro-

neia, not only do we come across the usual variety of

sigillata and red slip wares, but the survey pottery

assemblages also include different and presumably

town-specic lines of table-ware production, together

with a range of fabrics that we consider to be Greek

in character and that do not seem to correspond to the

production centres of table-wares attested at Athens

(Rotroff 1997a; 1997b), Corinth (Wright 1980; Slane

2003) or Patras (Hubner 1996; 2003). Furthermore,

new discoveries are bound to make our picture more

complex. Before 1987 nobody had ever heard of

Sagalassos red slip ware (Poblome 1999), yet this

class of pottery clearly represents a high-quality type

of table-ware that is comparable to any of the main

types circulating in the Roman East, and in its late

Roman phase of production formed part of the wider

Late Roman D tradition (Poblome and Frat 2011).

NETWORKS AND DISTRIBUTIONS

So far we have attempted to use the concept of con-

nectivity to explain phenomena from an artisanal pro-

duction point of view. In the second part of this

paper, we should like to present some considerations

as to how successful networking could provide also

for knock-on effects in distribution patterns. As in

the previous part, we propose an obvious example, a

more subtle one, and discuss some problems that

arise from all of them.

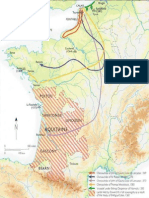

Plate 21.1 shows the distribution patterns of the

major types of table-ware in circulation in the late

Roman East, and is based on the published evidence

archived in the ICRATES database. African and

Phocaean red slip wares can be considered to be in a

league of their own, with other wares such as Cypriot

and Egyptian red slip wares representing more region-

ally focused patterns of distribution. From a network

point of view it is important to consider that Roman

pottery specialists agree that table-wares were not

traded for their own sake, but were assimilated into

existing ows of exchange. In this way, table-wares

become a strategic part of the exchange package,

although their patterns of distribution will never have

come about because of them. Ceramics of this kind

are, in other words, integral to the exchange patterns

of which they form a part, combining parasitic and at

the same time supportive roles within these patterns.

Often, this type of pottery represents the only archaeo-

logical trace of such networked exchanges.

In the next step pulling forces that is to say

economic, social, political, religious and cultural

forms of demand need to be taken into account in

order to explain the attested ows of exchange. These

forces are abstract notions that represent explicit or

implicit policies of different manifestations of auth-

ority. In the case of our example, Constantinople was

an obvious pulling force, which helps to explain the

higher presence of African red slip ware along the

route connecting it to the producing region. Obviously

many more factors including variable transport

infrastructure, levels of information and patterns of

demand need to be taken into account when

explaining specic ceramic assemblages in each of

these communities. In terms of networks, however,

Constantinople at least represented the potential of

association with this ow of exchange, which, to be

sure, did not come about simply as a result of table-

wares. It would be beyond the scope of this paper to

try and explain why a number of ows of exchange

were concentrated in Constantinople (Rickman 1980:

1989; Bonifay 2003: 11516, 11921, 1278;

Bonifay 2004: 479; Bonifay 2005: 5767; Pieri 2005:

148), and so we therefore propose to dene this role

in abstract terms by coining the eastern capital as a

framework of exchange. Such frameworks are

network nodes emitting sustainable pulling forces

with demonstrable archaeological effects. Other (and

mostly smaller) urban centres can be considered to

THOUGHTS ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESIDUE OF NETWORKS 397

have emulated this role, creating other frameworks of

exchange. These frameworks are all but static and

perform in both the geographical and chronological

sense. In the case of our example, we do not consider

the fairly high presence of African red slip ware in

the second half of the fourth century AD as well as

the contemporary arrival of Phocaean and Cypriot red

slip wares as coincidental, but that they resulted instead

from the initial brokering force of the Constantino-

politan node, in the wake of its foundation as a new

imperial capital. The fairly high presence of Phocaean

red slip ware in the northern Levant, on the other

hand, can be considered to have resulted from an

interplay between different frameworks of exchange.

Constantinople was tapping into the agricultural

potential of this region, possibly for its own supplies

but also for ensuring that the Danubian limes was

supplied. This region was functioning in what one

might term as a stable way, a situation attested by the

levels of production and distribution of the Late Roman

1 amphorae. Thus the high presence of Phocaean red

slip ware, followed by African red slip ware, in the

northern Levant did not originate fromdirect connections

between the regions of production and consumption, but

was brokered through the integrated functioning of

different frameworks of exchange, with Constantinople

as the main pulling and pushing force. In this sense the

presence of Phocaean and African red slip wares in the

northern Levant can be considered as a knock-on

effect of networking. Considering the scope of this

paper, other aspects represented in Plate 21.1 are left

undiscussed.

Other examples may not be as clear-cut as this, but

actually represent the majority of cases. When consid-

ering the situation of early Imperial table-wares in

Greece, for instance, the role played by Italian sigillata

at the colonia of Corinth nds no parallel (Slane 2004)

in the Roman East. This port, with its two harbours,

acted as an emporium where transshipment took

place, and thus, in terms of the regional distribution

of goods, it unsurprisingly nds itself at the apex of

the pyramid. When comparing the potters stamps on

Italian sigillata in Corinth, Argos, Athens, Kenchreai

and Olympia (Bes and Poblome 2006: 1567, table 4,

nos. 356), ICRATES looked for such patterns of

dependency. Clearly, Corinth stands out in having

most Italian sigillata and receiving it earlier than

anywhere else in Greece. For the other Greek sites,

an important proportion of the stamped pieces also

occurred at Corinth, which, together with similarities

in types and provenances of their table-ware, could

hint at some pattern of dependency on Corinth or

some distributive function for the latter. However this

is only part of the story and at each of the sites studied

Italian sigillata arrived by means of other routes; this is

especially true of Olympia, which, together with

Corinth (Slane 2004: n. 26), stands out with a particu-

larly large amount of late Italian sigillata (Martin 2006:

175, g. 1). In more general terms, we need to be aware

of the fact that in many cases we sense or suspect that

networking could be at play, but it is still difcult to

prove with good archaeological evidence.

In this sense, the principles of material culture

studies should protect us from providing excessively

positivistic answers when it comes to reconstructing

past networks. Some time ago, it was proposed that

a multi-layered exchange pattern existed between

Sagalassos and Egypt, involving goods, people and

ideas (Poblome and Waelkens 2003). Phrased in

network-terms, Sagalassos can be considered as a satel-

lite of the Alexandrian network, and it is very clear

which party beneted most from this relationship.

Recently, when looking at the inner Anatolian distri-

bution pattern of Sagalassos red slip ware and how

this correlated in general terms to the provenance of

some of the coins, sh and marble found in the town,

we started to think in terms of characterizing another

pattern of exchange. We started to have doubts, how-

ever. Indeed, the detail of the evidence calls for caution.

When looking at the numismatic evidence, for

example, most of the small change at Sagalassos

came from the local mint, demonstrating the existence

of a healthy economy or one in which economic

activity was maintained with a period of coin issue

(Poblome 2008). Coins from neighbouring Selge, and

from the second century AD onwards Pamphylian

Perge, added to the balance. Most other imported

coins are single issues from Pisidia and Pamphylia,

and a range of Phrygian sites. The latter do not

necessarily form a cluster, nor do they form part of an

intelligible exchange pattern, but they do indicate that

Sagalassos was not only oriented southwards but that

it was connected into the inner Anatolian road network

as well. While a detailed consideration of the marble,

pottery and sh (Van Neer et al. 2004) lies beyond

the scope of this paper, close inspection of the evidence

suggests that, like the coins, it has the potential to make

an important contribution to reconstructing operational

networks.

This kind of evidence is important, and raises the

question as to whether the seemingly lucky coincidence

of more than one category of material evidence is

398 POBLOME, BES & WILLET

sufcient for us to start thinking in terms of connec-

tivity. Clearly there will have been much exchange in

antiquity for non-systematic and sometimes even

coincidental reasons. Although we are convinced that

such relationships need to be studied and that in aggre-

gate they will mean something on the balance sheet of

the ancient economy, meaningful patterns of sustain-

able economic growth can come about only when

haphazard relationships are transformed into systematic

and interdependent networks. At the same time,

material culture specialists should be aware of the

inherent danger that the signicance of their simple

artisanal evidence can be exaggerated by third parties.

In this respect, there is also an urgent need to start docu-

menting the ipside of the coin, namely things that did

not function by network. It is thus important to consider

cases of deciency as well as success, because this

makes the ancient socio-economic balance sheet more

real.

ICRATES is involved also in processing ceramics

from the Hellenistic layers of Kinet Hoyuk or ancient

Issos. This town was booming in the late Hellenistic

period, amongst others, on account of Delos, and can

be considered to have been located in the core of the

Eastern sigillata A production region (Lund, Maltana

and Poblome 2006). Clearly, any port in this part of

Cilicia was potentially in a position to prot from this

increased level of activity, and Issos actually had two

ports (Gates 1998: 260). Our preliminary evidence

indicates, however, that Issos was ourishing in the

early days of Eastern sigillata A production but that,

for reasons as yet unknown, the site entered into a

period of decline in the rst quarter of the rst

century BC, resulting in its abandonment. This little

story indicates that although there can be a lot of

obvious archaeological criteria to indicate why and

where things went well, our limited capacity to under-

stand agency in antiquity should make us very careful

in interpreting such patterns. Nor should we forget

that things may not have gone well for the community

for much of the time, but that this is not readily gleaned

from archaeological literature or by archaeological

reasoning.

CONCLUSION

We should like to suggest that relating the study of

artefact distributions much more closely to evidence

for production is a very important clue to unravelling

networks in the Mediterranean. As things normally go

in classical archaeology, the most representative

ranges of artefacts with extensive distribution patterns

(for example the set of Late Roman amphorae, African

red slip ware, Italian sigillata and also Eastern sigillata

A) have received most academic attention. Without

wishing to play down the importance of these classes

of pottery, it seems worth considering the ways that

such wares have acted as an index against which to

judge the success of other artisanal products and

whether this comparative exercise does justice to

typical ancient modes of production.

Although ancient pottery production centres in the

Roman East are known very poorly, the available

evidence does support the notion that sizeable

manufacturing output was achieved by multiplying

small-scale production units rather than enlarging

existing facilities (McCormick 2001: 58). Such

processes of horizontal multiplication took place

within attested production centres, and we would like

to suggest that the widely distributed wares mentioned

above were the result of such processes of horizontal

multiplication involving many small-scale production

units within one or other region. They would have

resulted in so-called production conglomerates that

are typically associated with one or other framework

of exchange. In other words, the archaeology of

production units indicates that small-scale production

units geared towards their own regional markets are

to be regarded as the norm in antiquity. Obviously

this conclusion should cause us to change our focus

on distribution patterns, shifting it away from putting

more dots on the map, which seems to be the predomi-

nant interest of modern scholars, and concentrating

more upon understanding which markets artisanal

entrepreneurs had in mind, and what risks they were

prepared to take. Considering the fact that even the

highly successful types of table-ware in the Roman

East tended to be dominant in their own regions of

production indicates that entrepreneurs were reluctant

to take risks and that they mainly preferred the markets

they knew within their own regional radius or network.

It is only when conglomerates of production are present

that further markets are reached through the functioning

of frameworks of exchange. However, these conditions

are perhaps more exceptional than their representation

in the archaeological literature would seem to suggest.

The wide distribution patterns of these cases should

actually be considered as an aggregate of a patchwork

of outputs comprising many regional production centres,

with pulling forces that were not necessarily purely

commercial in nature, but possibly tied to larger

mechanisms instigated, implicitly or explicitly, by

THOUGHTS ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESIDUE OF NETWORKS 399

central authorities, such as the annona. In sum, a

production-linked focus on distribution patterns holds

great potential for approaching the contribution that

the artisanal sector made to ancient society, and part-

icularly to understanding past networks. Clearly, each

generation gets the classical archaeology it deserves,

and ours seems to be increasingly intricate.

Acknowledgements

The ICRATES Project is supported by the Fund for

Scientic Research, Flanders-Belgium (G.0.788.09).

Research at Sagalassos is funded by the Belgian

Programme on Interuniversity Poles of Attraction

(IAP 7/09), the Research Fund of the University of

Leuven (GOA 13/04), Project G.0562.11 of the Fund

for Scientic Research, Flanders-Belgium (FWO), the

Hercules Foundation (AKUL/09/16) and a Methusalem

Grant from the Flemish Ministry for Science Policy.

NOT E S

1. Networks are also discussed by Earl and his colleagues in

Chapter 23.

2. See Snodgrass (1987: 8990) for the third-century BC author

and traveller Herakleides.

RE F E R E NC E S

Bes, P.M. (2007) A Geographical and Chronological Study of the

Distribution and Consumption of Tablewares in the Roman

East. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Ph.D. thesis,.

Bes, P.M. and Poblome, J. (2006) A new look at old data: the

ICRATES platform. In D. Maltana, J. Poblome and J. Lund

(eds), Old Pottery in a New Century. Innovating Perspectives

on Roman Pottery Studies. Atti del convegno internazionale di

studi. Catania, 2224 aprile 2004 (Monograe dellIstituto

per i Beni Archeologici e Monumentali (IBAM) 1): 14165.

Rome, LErma di Bretschneider.

Bes, P.M. and Poblome, J. (2008) (Not) see the wood for the trees?

19,700 sherds of sigillata and what we can do with them. Rei

Cretariae Romanae Fautores Acta 40: 50514.

Bes, P.M. and Poblome, J. (2009) African red slip ware on the

move: the effect of Bonifays E

tudes for the Roman East. In

J.H. Humphrey (ed.), Studies on Roman Pottery of the

Provinces of Africa Proconsularis and Byzacena (Tunisia)

(Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 76):

7391. Portsmouth (RI), Journal of Roman Archaeology.

Bonifay, M. (2003) La ceramique africaine, un indice du developpe-

ment economique? Antiquite Tardive 11: 11328.

Bonifay, M. (2004) E

tudes sur la ceramique romaine tardive

dAfrique (British Archaeological Reports, International

Series 1,301). Oxford, Archaeopress.

Bonifay, M. (2005) Observations sur la diffusion des ceramiques

africaines en Mediterranee orientale durant lantiquite tardive.

In F. Baratte, V. Deroche, C. Jolivet-Levy and B. Pitarakis

(eds), Melanges Jean-Pierre Sodini (Travaux et memoires

15): 56881. Paris, Colle`ge de France.

Brughmans, T. (2010) Connecting the dots: towards archaeological

network analysis. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 29: 277

303.

Elton, H. and Reger, G. (2007) (eds) Regionalism in Hellenistic

and Roman Asia Minor (Ausonius etudes 20). Paris, De

Boccard.

Gates, M.H. (1998) 1997 Archaeological Excavations at Kinet

Hoyuk (Yesil-Dortyol, Hatay): XX. Kaz Sonuclar Toplants, I.

Cilt. 2428 mays 1998: 25981. Ankara, Kultur Bakanlg

Milli Kutuphane Basmevi.

Horden, P. and Purcell, N. (2000) The Corrupting Sea. A Study of

Mediterranean History. Oxford, Blackwell.

Hubner, G. (1996) Die Romische Keramik von Patras: Vorausset-

zungen und Moglichkeiten der Annaherung im Rahmen der

Stadtgeschichte. In M. Herford-Koch, U. Mandel and U.

Schadler (eds), Hellenistische und Kaiserzeitliche Keramik

des O

stlichen Mittelmeergebietes. Kolloquium Frankfurt

400 POBLOME, BES & WILLET

2425 April 1995: 15. Frankfurt, Archaologisches Institut der

Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universitat.

Hubner, G. (2003) Patras: Kreuzweg zwischen Ost und West. Die

Sigillatawaren aus dem Fundgut w 14, Korinthou 288/

Kanari. Rei Cretariae Romanae Fautores Acta 38: 25764.

Karagiorgou, O. (2001) LR2: a container for the military annona on

the Danubian border? In S. Kingsley and M. Decker (eds),

Economy and Exchange in the East Mediterranean during

Late Antiquity: 12966. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Lund, J., Maltana, D. and Poblome, J. (2006) Rhosica vasa

mandavi (Cic., Att. 6.1.13). Towards the identication of a

major tableware industry of the eastern Mediterranean: eastern

Sigillata A. Archeologia Classica 57: 491507.

Malkin, I., Constantakopoulou, C. and Panagopoulou, K. (2009)

Greek and Roman Networks in the Mediterranean. London,

Routledge.

Martin, A. (2006) Italian sigillata in the east: two different models

of supply (Ephesos and Olympia). In D. Maltana, J. Poblome

and J. Lund (eds), Old Pottery in a New Century. Innovating

Perspectives on Roman Pottery Studies. Atti del convegno

internazionale di studi. Catania, 2224 aprile 2004 (Mono-

grae dellIstituto per i Beni Archeologici e Monumentali

(IBAM) 1): 17587. Rome LErma di Bretschneider.

McCormick, M. (2001) Origins of the European Economy. Com-

munications and Commerce AD 300900. Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press.

Murphy, E. and Poblome, J. (2011) Producing pottery vs. producing

models: interpreting workshop organization at the potters

quarter of Sagalassos. In M.L. Lawall and J. Lund (eds),

Pottery in the Archaeological Record: Greece and Beyond

(Gosta Enbom Monograph 1): 306. Aarhus, Aarhus Univer-

sity Press.

Pieri, D. (2005) Le commerce du vin oriental a` lepoque byzantine

(V

e

VII

e

sie`cle). Le temoignage des amphores en Gaule

(Bibliothe`que archeologique et dhistorique 174). Paris,

Institut Francais du Proche-Orient.

Poblome, J. (1999) Sagalassos Red Slip Ware. Typology and

Chronology (Studies in Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology

2). Turnhout, Brepols Publishers.

Poblome, J. (2006) Made in Sagalassos. Modelling regional

potential and constraints. In S. Menchelli and M. Paquinucci

(eds), Territorio e produzioni ceramiche: paesaggi, economia

e societa` in eta` romana (Instrumenta 2): 35563, 4201. Pisa,

Edizione Plus/Pisa University Press.

Poblome, J. (2008) Sherds and coins from a place under the sun.

Further thoughts from Sagalassos. Facta. A Journal of

Roman Material Culture Studies 2: 191213.

Poblome, J. and Frat, N. (2011) Late Roman D. A matter of

open(ing) or closed horizons? In M.A. Cau, P. Reynolds and

M. Bonifay (eds), LRFW 1. Late Roman Fine Wares: Solving

the Problems of Typology and Chronology (Roman and

Late Antique Mediterranean Pottery 1): 4955. Oxford,

Archaeopress.

Poblome, J. and Waelkens, M. (2003) Sagalassos and Alexandria.

Exchange in the eastern Mediterranean. In C. Abadie-Reynal

(ed.), Les ceramiques en Anatolie aux epoques hellenistique

et romaine (Varia Anatolica 15): 17991. Paris, De Boccard.

Poblome, J., Ceulemans, A. and De Craen, K. (2008) The late

Hellenistic to late Roman ceramic spectrum of Tanagra.

Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique (20042005): 128

9, 56177.

Poblome, J., Corremans, M., Bes, P.M., Romanus, K. and Degryse,

P. (2008) It is never too late . . . the late Roman initiation of

amphora production in the territory of Sagalassos. In I.

Delemen, S. Cokay-Kepce, A. O

zdibay and O

. Turak (eds),

Euergetes. Festschrift fur Prof. Dr. Haluk Abbasoglu zum

65. Geburtstag: 1,0012. Antalya, Suna

_

I Inan Krac Research

Institute on Mediterranean Civilizations.

Reger, G. (2007) Regions revisited. Identifying regions in a Greco-

Roman Mediterranean context. Facta. A Journal of Roman

Material Culture Studies 1: 6574.

Rickman, G.E. (1980) The Corn Supply of Ancient Rome. Oxford,

Clarendon Press.

Romanus, K., Baeten, J., Poblome, J., Accardo, S., Degryse, P.,

Jacobs, P., Waelkens, M. and DeVos, D. (2009) Wine and

olive oil permeation in pitched and non-pitched ceramics:

relation with results from archaeological amphorae from Saga-

lassos, Turkey. Journal of Archaeological Science 39: 9009.

Rotroff, S.I. (1997a) Hellenistic Pottery. Athenian and Imported

Wheelmade Table Ware and Related Material. Part 1: Text

(The Athenian Agora XXIX). Princeton, Princeton University

Press.

Rotroff, S.I. (1997b) From Greek to Roman in Athenian ceramics.

In M.C. Hoff and S.I. Rotroff (eds), The Romanization of

Athens. Proceedings of an International Conference Held at

Lincoln, Nebraska (April 1996) (Oxbow Monographs 94):

97116. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Slane, K.W. (2003) Corinths Roman pottery. Quantication and

meaning. In C.K. Williams II and N. Bookidis (eds), Corinth.

The Centenary 18961996 (Corinth XX): 32135. Princeton,

Princeton University Press.

Slane, K.W. (2004) Corinth: Italian sigillata and other Italian

imports to the early colony. In J. Poblome, P. Talloen, R.

Brulet and M. Waelkens (eds), Early Italian Sigillata. The

Chronological Framework and Trade Patterns (BABesch

Supplement 10): 3142. Leuven, Peeters.

Snodgrass, A. (1987) An Archaeology of Greece. The Present State

and Future Scope of a Discipline. Berkeley/Los Angeles,

University of California Press.

Talloen, P. and Poblome, J. (2005) What were they thinking of?

Relief decorated pottery of Sagalassos. A cognitive approach.

Melanges de lE

cole Francaise de Rome. Antiquite 117: 5581.

Van Neer, W., Lernau, O., Friedman, R., Mumford, G., Poblome, J.

and Waelkens, M. (2004) Fish remains from archaeological

sites as indicators of former trade connections in the eastern

Mediterranean. Paleorient 30: 10148.

Wright, K.S. (1980) A Tiberian pottery deposit from Corinth.

Hesperia 49: 13577.

THOUGHTS ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESIDUE OF NETWORKS 401

You might also like

- The Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in EgyptFrom EverandThe Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in EgyptHarco WillemsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Network Models and Archaeological SpacesDocument23 pagesNetwork Models and Archaeological SpacesKarin ScharringhausenNo ratings yet

- Data Descripction and The Integrated Study of Ancient Near Eastern WorksDocument29 pagesData Descripction and The Integrated Study of Ancient Near Eastern WorksMARÍA CRESPO MARTÍNNo ratings yet

- The Connected PastDocument1 pageThe Connected PastMartin AdrianNo ratings yet

- ExperimentalDocument11 pagesExperimentalMai OshoNo ratings yet

- The Seeds of Commerce: A Network Analysis-Based Approach To The Romano-British Transport SystemDocument15 pagesThe Seeds of Commerce: A Network Analysis-Based Approach To The Romano-British Transport SystemCyrus BanikazemiNo ratings yet

- Archaeometry43 (2001)Document32 pagesArchaeometry43 (2001)pamant2No ratings yet

- Web Science Industry Forum Poster Session 2013Document35 pagesWeb Science Industry Forum Poster Session 2013Leslie CarrNo ratings yet

- Zoldfoldi Et Al CeramisDocument14 pagesZoldfoldi Et Al CeramisSzegedi Régészeti KlubNo ratings yet

- Evaluating authenticity of historic buildings using the Nara GridDocument8 pagesEvaluating authenticity of historic buildings using the Nara GridEmanuela Leite FragosoNo ratings yet

- 2008 09 12 - PerformingArtsDocument10 pages2008 09 12 - PerformingArtsMariel MoralesNo ratings yet

- CAA ReillyDocument7 pagesCAA ReillySamuel Lopez-LagoNo ratings yet

- Review of I. Malkin 2011. A Small Greek World. Networks in The Ancient Mediterranean. The Classical Review 63Document3 pagesReview of I. Malkin 2011. A Small Greek World. Networks in The Ancient Mediterranean. The Classical Review 63tom.brughmans8209No ratings yet

- Connected Histories: The Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500-1100 BCDocument32 pagesConnected Histories: The Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500-1100 BCJonNo ratings yet

- Cartas Portulanas PDFDocument28 pagesCartas Portulanas PDFArquivia ChinNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Visualization: Towards An Archaeological Information Science (Aisc)Document31 pagesArchaeological Visualization: Towards An Archaeological Information Science (Aisc)Lucas TheriaultNo ratings yet

- Network Art Practices and Positions Intr PDFDocument11 pagesNetwork Art Practices and Positions Intr PDFMosor VladNo ratings yet

- Past, Present and Future of Historical Information Science: Onno Boonstra, Leen Breure and Peter DoornDocument129 pagesPast, Present and Future of Historical Information Science: Onno Boonstra, Leen Breure and Peter DoornJitesh SahNo ratings yet

- More Than Meets The Eyes Archaeology Under Water Technology and InterpretationDocument16 pagesMore Than Meets The Eyes Archaeology Under Water Technology and InterpretationFilippo MatucciNo ratings yet

- Barberena Et Al 2017. Archaeological Discontinuities inDocument11 pagesBarberena Et Al 2017. Archaeological Discontinuities inLaurentidaSaNo ratings yet

- Research Article Fanet Göttlich, Aaron Schmitt, Andrea Kilian, Helen Gries, Kamal BadreshanyDocument17 pagesResearch Article Fanet Göttlich, Aaron Schmitt, Andrea Kilian, Helen Gries, Kamal Badreshanyjoaquin anaiz vasquez hernandezNo ratings yet

- Ceramics Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesCeramics Research Paper Topicsgw1w9reg100% (3)

- Seals Final Sept2014-Libre PDFDocument32 pagesSeals Final Sept2014-Libre PDFSimone Silva da SilvaNo ratings yet

- The Use of Prehistoric Big Data For Mapping Early Human Cultural NetworksDocument13 pagesThe Use of Prehistoric Big Data For Mapping Early Human Cultural NetworksRocio HerreraNo ratings yet

- (22134522 - Late Antique Archaeology) Artisans and Traders in The Early Byzantine City - Exploring The Limits of Archaeological EvidenceDocument41 pages(22134522 - Late Antique Archaeology) Artisans and Traders in The Early Byzantine City - Exploring The Limits of Archaeological EvidenceЈелена Ј.No ratings yet

- Rogers, 2013 - Social Archaeological Approaches in Port and Harbour StudiesDocument16 pagesRogers, 2013 - Social Archaeological Approaches in Port and Harbour StudiesGabriel Cabral BernardoNo ratings yet

- Roux ChaineOp OxfordDocument18 pagesRoux ChaineOp OxfordDaniel Davila ManriqueNo ratings yet

- Costis Dallas (1992) Information Systems and Cultural Knowledge: The Benaki Museum CaseDocument12 pagesCostis Dallas (1992) Information Systems and Cultural Knowledge: The Benaki Museum CaseCostis DallasNo ratings yet

- TEI and Cultural Heritage Ontologies Exchange of IDocument15 pagesTEI and Cultural Heritage Ontologies Exchange of Ibogdan alexandruNo ratings yet

- 7 Assassi and Mebarki 2112 PDFDocument15 pages7 Assassi and Mebarki 2112 PDFali khodja mehdiNo ratings yet

- AJA95MPSPDocument22 pagesAJA95MPSPxanthieNo ratings yet

- FHLLM 20190702Document71 pagesFHLLM 20190702Diego FirminoNo ratings yet

- Christine Hine - Virtual EthnographyDocument25 pagesChristine Hine - Virtual Ethnographylightmana100% (1)

- Studies 1 CH 5Document28 pagesStudies 1 CH 5bao ngan le nguyenNo ratings yet

- Baron 2014-Metapragmatics Interpreting Classic Maya Patron DeityDocument36 pagesBaron 2014-Metapragmatics Interpreting Classic Maya Patron DeityMoRi Kirni KirniNo ratings yet

- 2013 Museum Networks in The Mediterranean Area Real and Virtual Opportunities 2Document3 pages2013 Museum Networks in The Mediterranean Area Real and Virtual Opportunities 2Micaela Arratia IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Analysing Pottery Processing - Classification - Publication - Barbara Horejs - Reinhard Jung - Peter PavúkDocument33 pagesAnalysing Pottery Processing - Classification - Publication - Barbara Horejs - Reinhard Jung - Peter PavúkJovanovski Vladimir100% (1)

- Ali, N. 2010Document24 pagesAli, N. 2010María IsabellaNo ratings yet

- Restoring and Attributing Ancient Texts Using Deep Neural NetworksDocument22 pagesRestoring and Attributing Ancient Texts Using Deep Neural NetworksAkhilesh YadavNo ratings yet

- Capturing the Historical Research Methodology: An Experimental ApproachDocument11 pagesCapturing the Historical Research Methodology: An Experimental Approachkhuram pashaNo ratings yet

- ProQuestDocuments 2023 03 08 PDFDocument3 pagesProQuestDocuments 2023 03 08 PDFKat W (Tinkar)No ratings yet

- Research On Data Integration of Overseas Discrete Archives From The Perspective of Digital HumanitiesDocument13 pagesResearch On Data Integration of Overseas Discrete Archives From The Perspective of Digital HumanitiesijwestNo ratings yet

- Harbours and Maritime Networks As Comple PDFDocument1 pageHarbours and Maritime Networks As Comple PDFIdea HistNo ratings yet

- Landscapes of The MediterraneanDocument28 pagesLandscapes of The MediterraneanChad WhiteheadNo ratings yet

- Leshtakov09 Thassos2009Document34 pagesLeshtakov09 Thassos2009Ashok PavelNo ratings yet

- Archaeology: Spatial Analysis in Archaeology. Ian Hodder and Clive OrtonDocument3 pagesArchaeology: Spatial Analysis in Archaeology. Ian Hodder and Clive OrtonjackNo ratings yet

- Semantic Technologies For Historical ResearchDocument27 pagesSemantic Technologies For Historical Researchiis.afriyanti26No ratings yet

- A Future For Archaeology in Defense of An IntellecDocument10 pagesA Future For Archaeology in Defense of An IntellecPatricia OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Bernard Knapp - The Archaeology of Community On Bronze Age Cyprus Politiko Phorades in ContextDocument23 pagesBernard Knapp - The Archaeology of Community On Bronze Age Cyprus Politiko Phorades in ContextfmatijevNo ratings yet

- Research On Data Integration of Overseas Discrete Archives From The Perspective of Digital HumanitiesDocument14 pagesResearch On Data Integration of Overseas Discrete Archives From The Perspective of Digital HumanitiesijwestNo ratings yet

- Chase Et Al Geoespacial Mesoamerica 2012Document6 pagesChase Et Al Geoespacial Mesoamerica 2012Catalina VenegasNo ratings yet

- A Database For Archaeological Data Recording and Analysis: Anichini F., Fabiani F., Gattiglia G., Gualandi M.LDocument18 pagesA Database For Archaeological Data Recording and Analysis: Anichini F., Fabiani F., Gattiglia G., Gualandi M.LyamiyxopNo ratings yet

- Ten Years On: The Community Archaeology Project Quseir, EgyptDocument17 pagesTen Years On: The Community Archaeology Project Quseir, EgyptAdam T. AshcroftNo ratings yet

- Texto 10 - 2020, Archaeology and Spatial Analysis - CAPDocument17 pagesTexto 10 - 2020, Archaeology and Spatial Analysis - CAPAna FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Kin Tigh 2015Document15 pagesKin Tigh 2015Renan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Ethnoarchaeology: A Non Historical Science of Reference Necessary For Interpreting The PastDocument27 pagesEthnoarchaeology: A Non Historical Science of Reference Necessary For Interpreting The PastMorriganRodriNo ratings yet

- Prehistory Newsletter: Lectures, Books and MoreDocument18 pagesPrehistory Newsletter: Lectures, Books and MoremsugermanNo ratings yet

- Political and Economic Interaction on the Edge of Early EmpiresDocument15 pagesPolitical and Economic Interaction on the Edge of Early EmpiresAngel JordánNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Archaeological JournalDocument20 pagesCambridge Archaeological Journalhenrialbert510No ratings yet

- Analogy in Archaeological Interpretation. AscherDocument10 pagesAnalogy in Archaeological Interpretation. AscherPaula TralmaNo ratings yet

- 01-02 Bd. I. 1-2 (Aal-Apollokrates)Document736 pages01-02 Bd. I. 1-2 (Aal-Apollokrates)zamindarNo ratings yet

- The Treaty of Brétigny/Calais (1360) and The Campaigns of The Second Phase of The WarDocument1 pageThe Treaty of Brétigny/Calais (1360) and The Campaigns of The Second Phase of The WarzamindarNo ratings yet

- Amedroz Margoliouth IIIDocument470 pagesAmedroz Margoliouth IIIzamindarNo ratings yet

- Qalanisi - Amedroz - History of DamascusDocument460 pagesQalanisi - Amedroz - History of DamascuszamindarNo ratings yet

- Tractatus de Locis Sancte TerreDocument11 pagesTractatus de Locis Sancte TerrezamindarNo ratings yet

- The Laws of Croatia-LibreDocument85 pagesThe Laws of Croatia-Librezamindar100% (1)

- Saladdin LIfe of Saladdin Life of SaladinDocument471 pagesSaladdin LIfe of Saladdin Life of SaladinzamindarNo ratings yet

- Albert Us Magni ViiDocument807 pagesAlbert Us Magni ViizamindarNo ratings yet

- Aass - Acta+Sctorm September IIIDocument1,061 pagesAass - Acta+Sctorm September IIIzamindarNo ratings yet

- Ma Us Sant Ball Fat Complete StoriesDocument1,027 pagesMa Us Sant Ball Fat Complete StorieszamindarNo ratings yet

- Zuravlev LightingEquipmentRomanLateRomanPeriodDocument29 pagesZuravlev LightingEquipmentRomanLateRomanPeriodzamindarNo ratings yet

- Google Book Search ProjectDocument425 pagesGoogle Book Search ProjectzamindarNo ratings yet

- Update Florida Do Not Call Registration DetailsDocument1 pageUpdate Florida Do Not Call Registration DetailszamindarNo ratings yet

- Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)Document935 pagesVuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)krca100% (2)

- Magazine Edinburgh Scotland Ninettenth CntrysaDocument1,019 pagesMagazine Edinburgh Scotland Ninettenth CntrysazamindarNo ratings yet

- Ashburner FarmersLawIDocument25 pagesAshburner FarmersLawIzamindarNo ratings yet

- Absorption Chillers HVACDocument75 pagesAbsorption Chillers HVACzamindarNo ratings yet

- The Only Desalination That Pays For Itself!Document10 pagesThe Only Desalination That Pays For Itself!zamindarNo ratings yet

- 2011 Kentucky Derby EasyformDocument4 pages2011 Kentucky Derby Easyformzamindar100% (1)

- Al FakhriDocument557 pagesAl FakhrizamindarNo ratings yet

- BGAVIIIDocument564 pagesBGAVIIIzamindarNo ratings yet

- BNCATANTIQUEDocument661 pagesBNCATANTIQUEzamindarNo ratings yet

- 01-02 Bd. I. 1-2 (Aal-Apollokrates)Document736 pages01-02 Bd. I. 1-2 (Aal-Apollokrates)zamindarNo ratings yet

- Scarborough HerbsFieldDocument13 pagesScarborough HerbsFieldzamindarNo ratings yet

- EpistolaeMoguntinae Monumenta MoguntinaDocument774 pagesEpistolaeMoguntinae Monumenta MoguntinazamindarNo ratings yet

- Inbaa Ghomr 03Document611 pagesInbaa Ghomr 03zamindarNo ratings yet

- Inbaa Ghomr 00Document1 pageInbaa Ghomr 00zamindarNo ratings yet

- Inbaa Ghomr 01Document585 pagesInbaa Ghomr 01zamindarNo ratings yet

- Inbaa Ghomr 02Document584 pagesInbaa Ghomr 02zamindarNo ratings yet

- Visions of The Apocalypse - Beatus Manuscripts and 13th Century Apocalypse ManuscripsDocument15 pagesVisions of The Apocalypse - Beatus Manuscripts and 13th Century Apocalypse Manuscripsalice85aliceNo ratings yet

- Material Price CIDB 2019Document18 pagesMaterial Price CIDB 2019Nur Aishah YNYNo ratings yet

- A Project On Nagarjuna DamDocument3 pagesA Project On Nagarjuna Damapi-19889358No ratings yet

- Secondary Unit: Teacher GuideDocument30 pagesSecondary Unit: Teacher Guideapi-406109711No ratings yet

- Hei2017directory PDFDocument316 pagesHei2017directory PDFRishab WahalNo ratings yet

- 7 Grade Internet Safety Project - Skit Rubric: Category 5 4 3 2 1Document2 pages7 Grade Internet Safety Project - Skit Rubric: Category 5 4 3 2 1adni_wgNo ratings yet

- Gadpayle & Associates: Plannerengineervalueristructural DesignerDocument6 pagesGadpayle & Associates: Plannerengineervalueristructural DesignerraviNo ratings yet

- Design and Technology: Paper 6043/01 Paper 1Document7 pagesDesign and Technology: Paper 6043/01 Paper 1mstudy123456No ratings yet

- Music Theory CHP 5Document9 pagesMusic Theory CHP 5Caleb NihiraNo ratings yet

- BrassDocument1 pageBrassapi-312756467No ratings yet

- Euphonic Sounds22 PDFDocument3 pagesEuphonic Sounds22 PDFAngie0% (1)

- Vol. 10 Morgan C. Attic Fine Pottery of Archaic Tic Periods in PhanagoriaDocument310 pagesVol. 10 Morgan C. Attic Fine Pottery of Archaic Tic Periods in Phanagoriabart19870% (1)

- Cursive Handwriting Practice Grids PDFDocument55 pagesCursive Handwriting Practice Grids PDFJuan Carlos Mazzarello UrzuaNo ratings yet

- Four Contemporary Poems in TranslationDocument28 pagesFour Contemporary Poems in TranslationJunley L. LazagaNo ratings yet

- No Fines Concrete:: A Practical GuideDocument2 pagesNo Fines Concrete:: A Practical GuideAdhil RamsurupNo ratings yet

- Design Elements Typography Fundamentals PDFDocument161 pagesDesign Elements Typography Fundamentals PDFDinh Dung100% (2)

- Music10 - q3 - Mod1 - Musika Natin Ito Contemporary Philippine MusicDocument16 pagesMusic10 - q3 - Mod1 - Musika Natin Ito Contemporary Philippine MusicMark GutangNo ratings yet

- Designing A Dining RoomDocument7 pagesDesigning A Dining RoomArjun BSNo ratings yet

- Good Christian Friends Rejoice PDFDocument1 pageGood Christian Friends Rejoice PDFHousi WongNo ratings yet

- How To Cut With Silhouette CameoDocument12 pagesHow To Cut With Silhouette CameomixemeyartNo ratings yet

- Salon Artist and The Rise of The Indian PublicDocument29 pagesSalon Artist and The Rise of The Indian PublicvivekNo ratings yet

- Pearl Sweater: Mrs - Deer.KnitsDocument6 pagesPearl Sweater: Mrs - Deer.KnitsSophie Cimon100% (1)

- Blurring Architecture by Toyo ItoDocument10 pagesBlurring Architecture by Toyo Itopiki_tunningNo ratings yet

- Crochet Headband With A Twist - Free Pattern - Croby PatternsDocument10 pagesCrochet Headband With A Twist - Free Pattern - Croby PatternsalexandraNo ratings yet

- Indice de Los BoletinesDocument78 pagesIndice de Los BoletinesrodolfoNo ratings yet

- Torrent Description (READ Me)Document2 pagesTorrent Description (READ Me)Ben DavidsonNo ratings yet

- Architecture Student Portfolio - Namira 2021Document43 pagesArchitecture Student Portfolio - Namira 2021Namira JmlNo ratings yet

- Standing Chancery - A Series of Training DrillsDocument11 pagesStanding Chancery - A Series of Training DrillsAChom100% (1)

- Checklist For Curtain Wall & Glazing InstallationDocument1 pageChecklist For Curtain Wall & Glazing InstallationChristos Loutrakis100% (1)

- MusicDocument278 pagesMusicGandhi WasuvitchayagitNo ratings yet