Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pollan, Michael OnlyMansPresenceCanSaveNature

Uploaded by

lulugovindaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pollan, Michael OnlyMansPresenceCanSaveNature

Uploaded by

lulugovindaCopyright:

Available Formats

F o R u M

ONLY M AN'S

PRESENCE CAN

SAVE NATURE

Te ongoing public con-

versation about the environment is grounded in the

ancient dichotomy of man versus nature. So far we

have sought to resolve the argument through aseries

of truces-either sequestering large tracts of wilder-

ness in astate of imagined innocence, say, or limiting

the ways in which man can domesticate nature's

imagined savagery. A recent contribution to this

conversation suggests that we have postponed too

long atrue settlement and that man isnow talking to

himself Nature has ended.

But others say that we must radically change the

conversation and begin to talk not of man versus

nature but of man and nature. This line of thinking

suggests that we must discard what is, in fact, afalse

dichotomy and find new answers to old questions.

What do we see when we look into a quiet stand of

trees? Lumber? The planet's breathing apparatus?

The habitat of animals? Home? In order to examine

the rapidly changing metaphors that locate man's

place in the world, Harper's Magazine recently asked

five environmentalists with backgrounds in science,

political activism, or philosophy to discuss the shift,

ing definitions of nature and of ourselves.

FORUM 37

The following forum is based on a discussion held at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in New York City.

Michael Pollan served as moderator.

MI CHAEL POLLAN

is executive editor of Harper's Magazine.

DANIEL B. BOTKIN

is professor of biology and environmental studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara

and the author of Discordant Harmonies: A New Ecologyfor the Twenty-first Century, which will be

published this month by Oxford University Press.

DA VE FOREMAN

was chief lobbyist for the Wilderness Society and cofounded the environmental group Earth

First! in 1980. Heis the author of Ecodefenseand The BigOutside. His book Confessionsof an Eco-Brute

will be published by Crown this winter.

JAMES LOVELOCK

is an independent scientist who developed the Gaia theory, which regards our planet as a self-regulating system

that behaves as if it were a living organism.

FREDERICK TURNER

isFounders Professor of Arts and Humanities at the University of Texas at Dallas and the author

of the epic poem Genesis. His last piece for Harper's Magazine, about the cultivation of life on Mars,

appeared in the August 1989issue.

ROBERT D. YARO

is senior vice president of the Regional Plan Association in New York City, where he is preparing a new

regional plan to manage future growth in the New York tri-state metropolitan region.

Beyond the Wilderness

MICHAEL POLLAN: Let us saywe're in the town of

Pineville, Connecticut. On the edgeof town is

astand of virgin pine trees left to Pineville years

ago with the stipulation that it be "kept in a

state of nature." Known as the Tabernacle

Pines, this forest is extraordinary, with trees

more than 150 feet tall. A hurricane came

through recently and devastated the forest. Sev-

enty percent of the trees aredown. The place is

a mess, almost impassable. I amthe curator of

this forest, and I have to make a recommenda-

tion to the town. Do weleaveit asit is-is that

astate of nature?-or do weclear it out and re-

plant pine, so that the next generation might

enjoy some semblance of the old forest?

DAVE FOREMAN: Leave it as it is. Too often we

think that nature isasnapshot in time. I t's not.

Nature is a continually evolving process. A

largetree isoften more important after it falls.

POLLAN: I mportant in what sense?

FOREMAN: A Douglas fir may stand for 800 years

and provide various services to the lifearound

it. After it falls, it provides even more services

for the next 500 years-to beetles, termites,

and fungi.

38 HARPER'S MAGAZI NE I APRI L 1990

DANIEL BOTKIN: I t's been shown that the shape and

formof a stream and the life in it are often a

function of the trees living and fallingalong the

banks.

Forestsarenot static. They have abiography

not unlike ahuman's. Their infancy isthe open

field or devastated forest. First, "pioneer spe-

cies" begin to grow: herbs, grasses, and then

shrubs. Afterward there are several stages of

trees. These stages are dynamic and diverse.

The forest's maturity isknown asits"dimax"-

amorestable andlessdiversemixof speciesthat

will persist for some time. I n old age, a forest,

such as the Tabernacle Pines, becomes sus-

ceptible to fire or hurricane. These stages of

development, or forest succession, are quite

interconnected. Takeyour fallen trees. Certain

seeds regenerate best when they fall into the

nest of a rotting log.

FOREMAN: Often youwill seea"nurse log," with a

series of trees growing out of it. After the log

decays, you can sometimes see an archway in

the roots. A forest will rejuvenate better if it's

not replanted. When wetry to jump-start the

natural stagesof forest development by replant-

ing, weremove necessary nutrients, such asrot-

ting logs, and the forests arecrippled. Nature is

not a pretty, manicured place maintained for

human beings. It isadynamic continuum, often

a violent one.

J AMES LOVELOCK: If the land issurrounded byother

forested areas, I agree. If the Tabernacle Pines

were an island of trees, I think i~would have

been akind of garden anyway. It might bemore

proper-even natural-to replant and rebuild.

FREDERICK TURNER: Leaving the land alone is at-

tractive, bur, asJ ames Lovelock says, it might

beasnatural to do something with it. Certainly

nature isnot amanicured garden. Nature isaset

of complicated feedback sys-

tems, constantly exchanging

information. Some are self-

duplicating-preserving the

systemas it is-and they are

called homeostatic. Others

are open-ended systems, con-

stantly creating novel states

and new ecologies. In an

open-ended system, the most

crucial element is the human

species. So I would saythat if

the town is not involved in this question of

leaving the forest alone or replanting it, one

would then be violating nature, because absent

fromthis process is the quintessential element

of nature-us. Humankind ismore what nature

isthan anything else.

POLLAN: Not just equal but more?

TURNER: More. Consider the fundamental tenden-

cyof evolution fromthe bigbang to the higher

animals. It isatendency towardgreater reflexiv-

ity, greater open-endedness, greater complex-

ity, and greater "encephalization"-that is, a

larger proportion of nervous tissue. Evolution in

pre-living chemical systems occurs slowly and

has no way of changing itself. Sexually repro-

ducing lifecan record itself and then reshuffle

and recombine the recordings. It can improve

itself; that isevolution. Then you have organ-

isms that thrive in societies, which is just

another, perhaps more sophisticated, way of

passing on information to another generation.

Nature has had this tendency toward increas-

ingly more complex ways of passing on infor-

mation from the big bang all the way up.

Humankind iswhat nature has been trying, all

these millennia, "to be."

BOTKIN: My problem iswith the language "a state

of nature." Nature does not exist in one state

but in many states. If nature achieved a single

natural state, then the answer to all environ-

mental problems wouldbe to let nature growto

that state. But once one knows that nature is

dynamic, with changing states and different fu-

tures-and that these states range literally from

fireto ice, with avariety of possible landscapes

in between-then the choice becomes ours,

mankind's, and that choice is "natural." So

what is the nature weprefer? If you scratched

beneath the assumptions of the average New

Englander, youwoulddiscover that the ideaof a

"THE LANDSC

ARTIFICIAL AS C

IT MAY NOT

LANDSCAPE OF

POLLAN: Are you sayingthat without man's inter-

vention, nature doesn't know what is best for

the planet?

TURNER: If one made the decision without human

beings. then the decision would be, I think,

unnatural.

'\ NECTICUT IS AS

NEW YORK CITY.

ED, BUT THE

oIS A HUMAN

"forest" iswhat the Pilgrims saw. It's asgood a

forest asany, so I would let the area growback

through the particular stages of succession that

the Pilgrims saw. This means gardening the for-

est and weeding out the exotics-those species

introduced by Europeans.

POLLAN: Y ouwould weed?

BOTKIN: Y es,the ailanthus, or treeof heaven; J apa-

nese honeysuckle; the exotics. I'd do a little

behind-the-scenes management.

ROBERTYARO: I wouldleavethe land alone, but for

a different reason. The landscape of Connecti-

cut isas artificial as Central Park in New Y ork

City. It may not be as contrived, but the land-

scapeof New England isahuman creation. Un-

likeyour England, Professor Lovelock, which is

an over-tended "garden," New England is an

under-tended garden. Early in this century,

Massachusetts conducted an inventory of scenic

landscapes and foundafewremnants of forest in

an otherwise open agricultural landscape. Fifty

years later, when I conducted a similar inven-

tory. I found that only 10percent wasagricul-

tural and most of the rest was second-growth

forest. Connecticut isquite similar. So I would

leaveTabernacle Pines alone sothat the people

could learn the natural processes that shape

their landscape. Dr. Botkin's goal of creating

the forest succession of the Pilgrimerawon't be

useful on these few acres. I would turn to the

larger canvas of the abandoned New England

landscape. There are 130,000 acres of public

FORUM 39

land in Connecticut.

Let's manage it and re-

createamassivePilgrims'

forest.

LOVELOCK: The Tabernacle

Pines were knocked

down by a hypothetical

hurricane. In fact, there

have been many real

hurricanes here, in En-

gland, and e.lsewhere.

And we're getting more

of them. I might follow

E. F.Schumacher's max-

im: Act locally, think

globally.Thus, onewon-

ders if it is sensible to

plant the same kind of

pineswhentheglobal cli-

mateischangingsomuch

now.

POLLAN: What might be a

goodalternative?

LOVELOCK: Letnatureselect

whatever would best

survive under these new

conditions.

TURNER: The point

about genetic material is

critical. What might we

want in our new forest?

For example, should our

goal be to maximize

biomass-that is, the

weight or massof living

material?Buthowdoyou '

define "living"? What

about mostof acoral reef

or heartwood, which is

dead?Should thegoal be

to maximiie the massof

livingtissueor maximize

the mass of DNA and

RNA, the carriersof he-

redity? Should we farm

theplanet forgenetic di-

versity? But one might

think, Doesn't this idea

slight other means of

passing on information

between generations-

learning, rituals, librar-

ies, this conversation,

computers? Therefore,

shouldwemaximizener-

voustissue-or the den-

sity of human culture-since that would maxi-

mizethe amount of information getting passed

on ro other generations?

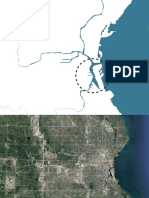

On July 10, 1989, a stand of 200- to300-year-

old trees in Connecticut called the Cathedral Pines

(top) was devastated by a tornado (bottom), pro-

voking a debate about what should be the "natu-

ral" disposition of a tract of damaged land. One

side argued that the owner, The Nature Conser-

vancy, should clear the area and replant it. An-

other side held that the forest should be left to

decompose and regrow on its own. Recently, The

Nature COTl5ervancy decided toclear the perimeter

of the Pines in order to manage any potential !ires.

The center-full of downed trees, splintered

trunks, and uprooted stumps-will remain in a

"state of nature." The hypothetical forest dis-

cussed in the opening section of this forum is based

on this cata.$trophe,

BOTKIN: But the migration

of the seedsisno longer

possible from, say, the

southern areas. So if you

want to go that route,

youwouldhave to go to

Virginia, collect the

seeds, and then plant

Virginiapineor southern

pine.

POLLAN: SOaren't wereally

talking about gardening our state of nature, not

leavingit alone?

FOREMAN: To adegree. First, weneed to recognize

that your Tabernacle Pines are tied not only to

Connecticut and New England but to Central

American rain forests. The songbird popula-

tion-which needs all these habitats-is crash-

ingright nowbecauseof thedestruction of these

forests.

Second, there is the opportunity for wilder-

ness restoration on a grand scale in New En-

gland. One of the largest uninhabited areas in

America isin northern Maine, 10 million acres

without year-round inhabitants that stretch

down to northern Vermont, New Hampshire,

and the Adirondacks. Within my lifetime we

could have a preserve in New England-with

wolf, caribou, moose, and eastern panther-ri-

valing those inAlaska. Wemust usethe ideasof

42 HARPER'S MAGAZINE / APRIL 1990

conservation biology:

core wildernessreserves,

surrounded by buffer

areas in which steadily

decreasinghuman useis

allowed as weget closer

tothecore, withbiologi-

cal corridors connecting

thecorepreservesfor the

transmission of genetic

material and wildness.

'.

BOTKIN: The idea that we should find a single

quantity tomaximize isintellectual baggagefrom

the nineteenth century. It isessentially the me-

chanical ideal, the metaphor of the engine with

one peak of humming power. This metaphor co-

alesced with the ancient notion of adivine or-

der-s-that nature was perfect. This union of

ideas yielded the falseviewof nature asasingle

pristine state-undisturbed and without man;

There is no such nature. Ecological systems

have values other than "peak performance."

The relationship between human beings and

these natural systems is much more complex

and more organic than the machine metaphor

allows usto see. When weseeourselves aspart

of this dynamism of nature, wewill have amore

accurate metaphor and view of the world.

TURNER: Exactly mypoint. We're going to have to

strive for all of these goals simultaneously.

POLLAN: I'mabit alarmed that each of youiswill-

ingto interfere and makethese decisions for na-

ture. What isthe measureof our actions? What

is too much, too little?

FOREMAN: It'ssomething we'regoingtobelearning

for the next thousand years. It's important to

distinguish between native diversity-the life

that has historical ties to apiece of land-and

natural diversity-the lifethat will move onto

a piece of land. Generally, those species that

come in are "weed" species. We're finding out

now, for example, that in the ancient forestsof

the Pacific Northwest, the marbled murrelet

and the red-backed vole and the flyingsquirrel

are losing habitat to the species adapted to

disturbed ecosystems. For example, the white-

tailed deer, in theNorth at least, isaweedspe-

cies that has expanded its range as humans

disrupt the environment, replacing caribou and

moose.

LOVELOCK: I'm fascinated to hear Dave Foreman

usethe wordweed! It's adreadful word, isn't it?

TURNER: Isn't aweed aweedprecisely because it's

good at spreading itself around, and wouldn't it

be unnatural to stop it from doing so? Why

should weprivilege the genetically lessrobust?

Maybeweeds have a lot going for them.

BOTKIN: Maybeweshould clarifywhat aweedis. A

weed is to plants as dirt is to soil. A weed is a

plant out of place. So aredwoodtree inthe des-

ert isaweed. European weedsspread very well.

They cameover on the hosts of European ships,

with cattle and hay. The most troublesome

weeds arrive in the early stages of forest suc-

cession. If not weeded, for example, J apanese

honeysuckle can overwhelm asturdy hardwood

stand in eastern North America.

FOREMAN: Spotted knapweed inMontana, tumble-

weed in the Southwest, kudzu in the South-

east-ali areweeds. But look at why they exist.

I spent eight years locating the large roadless

areas inthe United States, and I foundonly 368

areas of more than 100,000 acres apiece in the

West and 50,000 inthe East. Inother words, 92

percent of the lower forty-eight states has been

developed. So wecould try to reclaim some of

the 92 percent. For example, the 10 million

acres inMaine that I mentioned areowned bya

few paper companies. The government could

buy that land today for the price of acouple of

Stealth bombers.

YARO: Dave, consider that the lfl-rnillion-acre for-

est in Maine is one of the last places in the

Northeast where we have a resource-based

economy. People work in the forest cutting

treesandwork inthe millsturning the trees into

paper-all of which relates to the people who

pick upthe New York Times inthe morning. We

shouldn't throw out the people and the econ-

omy to "save" the forest. Saveboth. A goodex-

ample of this problem occurred in Cades Cove

in the Smokies. The National Park Service

came in sixty years agoto "preserve the Smok-

ies" and threw out the local Appalachian peo-

ple. Topleasethe tourists, they havenow hired

costumed actors posing as Appalachians. We

can introduce human use that isn't in conflict

with preserving an intact ecosystem.

POLLAN: A preserve that includes Homo sapiens?

YARO: Yes. Last year I made trips to two similar

landscapes-the Alps and Mount Rainier. In

the Alps, I found beautiful landscapes that in-

cluded villages, farms, factories, agriculture,

and eventually wilderness. There was no na-

tional park and no artificial boundary between

the natural and humanized areas. Then, Mount

Rainier. There's alineon the map. On one side

of it, we'vekicked out the local people. It's well

kept insidethepark but dull incomparison to its

Swisscounterpart. Once youcross the line, all

hell breaks loose. It's as though two alien cul-

tures met at the national-park boundary. Out-

sideof it areticky-tacky signs, ski areas, and fast

food. Now why can't wemove the line of the

park out but allow for certain human activity

that reinforces what's there?

POLLAN: Let's return to Tabernacle Pines. There

arehouses bordering it. Forestryexperts tell me

that if I leavethe drying, rotting logs, I can ex-

pect amajor firethat would threaten the town,

especially the property on the border.

BOTKIN: Tell them to go to Hartford and get fire

insurance.

YARO: Insurance isanative industry in Connecti-

cut, and weshould respect it!

LOVELOCK: Without forest fires, youwouldn't have

long-termoxygen regulation in the atmosphere.

So if westop all fires, wemayharmourselves in

the long run.

POLLAN: Will you come with me and explain that

to the fellowwhose house is in danger?

LOVELOCK: Hard cases make bad law, don't they?

Still, it's the only way, and sornebody'sgoing to

be hurt.

FOREMAN: Why does nature alwayshave to make

the adjustment instead of people?

TURNER: Nature versuspeople again. I simplydon't

buy it. I want to register aprotest about this and

FORUM 43

the 92 to 8 percent distinction. It is artificial.

The Indians-the people who came across the

Bering Land Bridge-changed the ecology of

North America totally. And beforethat, the ice

agesdrastically altered these lands.

POLLAN: Isthere adistinction between thechanges

wrought by humanity and the changes wrought

by the ice ages?

BOTKIN: Yes. Essentially, the differences are the

rate of change and man's introduction of novel

actions. Trees migrate, but over thousands of

years. In Michigan, Paul Bunyan's country, 19

million acres of white pine were logged in less

than ahundred years. Plowingisanovel action,

and we should avoid too much of it. Many

chemicals are totally novel, soweshould avoid

them aswell. Again, weshouldn't treat nature

as if it's a machine-take it apart, rebuild it,

and substitute new parts. The rule should be:

Change nature at nature's rates and in nature's

ways.

YARO: Our problem stems froma wilderness ethic

that puts lines on maps and fences on the

ground and says, "Keep your hands off." This

ethic finds its complement in our land ethic,

which says, "Take the money and run." This

must end. We must manage our continent.

LOVELOCK: And that problem is made worse by

agribusiness. Wehave plowedup somuch more

than weneed. England isspending billions just

to store its surplus grain. At one time, butter

frommy part of Britain wasactually burned in

German power stations.

POLLAN: Dave, areyousanguine when youhear all

this optimistic talk about reconciling the inter-

ests of man and nature?

FOREMAN: No, I'mnot. In studying evolution, we

learn that the worst thing aspeciescan beistoo

successful. That's the stagewe're in. But weare

living in afool's paradise. We've ended agiddy

drunk, and anasty hangover awaitsus. It might

beAIDS, it might be something else. I want to

make sure that wedon't take everything with

us. Believingthis isthe only thing that givesmy

lifemeaning.

Our problemisaspiritual crisis. The Puritans

brought with them a theology that sawthe wil-

derness of North America as a haunt of Satan,

with savagesashis disciples and wildanimals as

hisdemons-all of which had tobecleared, de-

feated, tamed, or killed. Opening up the dark

forests became a spiritual mission: to flush evil

out of hiding. If we are going to survive in

North America, we have to go back, meta-

phorically, to that pilgrim shore again. Let's

seek to learn fromthe land this time. I do be-

lieve that people are tied into nature. I don't

44 HARPER'S MAGAZINE I APRIL 1990

want to separate humans fromnature, But we

must discover our proper place inthat dynamic.

Consider that Phoenix, Arizona, has one of the

highest per capita water uses in the United

States! People in Denver, Colorado, all have

lawns requiring eleven inches of rain a week,

just like English lords.

POLLAN: Are wethreatening ourselves, the planet,

or both?

FOREMAN: All of it. Ecologist Paul Ehrlich saysthat

killing off species is analogous to taking rivets

out of an airplane: J ust one rivet, wecan get by;

but at somepoint, theairplane isno longer safe.

LOVELOCK: Paul Ehrlich propagates this notion of a

fragileEarth. It's not Earth that's fragile; it's we

who arefragile. Nature has withstood catastro-

phes far worse than what we've delivered.

Nothing wedo will destroy nature. But wecan

easily destroy ourselves.

Dave, weprobably will experience a sudden

drop in population, and comparatively soon. It

won't happen here, of course, but inthe tropical

regions, where the sustaining forests are more

gravely threatened. The humid, tropical forest

regions house about a billion people. Once

we'vecleared 70 percent of the forests-which

wearewell on the wayto doing-the remainder

won't be able to sustain the region's climate.

Without the rain, the trees will die. Wemaysee

this asearly as2000. And when that happens, a

billion people will be facing death and starva-

tion. Wewill have arefugeeproblem and apo-

litical crisis as bad as a thermonuclear war.

FOREMAN: The naturalist Aida Leopold said there

are those who can livewithout wild things and

those who cannot. I amone of those who can-

not. I'maproduct of the Pleistocene epoch, the

ageof largemammals. I ama large mammal. I

like large mammals. I do not want to live in a

worldwithout jaguars and great bluewhales and

redwoods and rain forests, because this is my

geological era, this ismyfamily, this ismycon-

text. I only have meaning in situ, in the age I

livein, the latePleistocene. I donot want to be

the cause of a transition into a new era.

Designing Nature

POLLAN: Becauseof mv brilliant disposition of the

issue of Tabernacle Pines-suffice it to say I .

took your advice-I waselected mayor of neigh-

boring Oakdale. Recently, an old woman died

and left a square mile of land on the edge of

town toOakdale. Her will stipulates that weuse

this land "for the benefit of Oakdaleans." The

parcel has a moderate-size farm surrounded by

second-growth oak forest. There's abluff over-

looking the farm and

the famousTreaty Oak,

where the Indians first

made friends with the

settlers. The bluff is

wherefivegenerationsof

Oakdaleans have come

to court; it has its own

history. Now I am em-

powered to decide what

happens to this land. I

ran on a solid environ-

mental ticket, and yet I

alsofacea15percent un-

employment rate among

the working class; pres-

sureisbuildingto devel-

oponthisland. What do

I do?

TURNER: Allow limitedde-

velopment, but balance

that by planting, witlUn

the town limits, indig-

enous species, thus ex-

tending their range.

Erase the boundary be-

tweentheurbanizedarea

and nature. You might

alsoofferproperty-taxex-

emptions for thenumber

ofspeciesbeingpreserved

on your land. Losespe-

ciesandyou'dpayahigh-

er tax.

YARO: He's assuming, Mr. Mayor, that you don't

want to get reelected!

BOTKIN: I'd start with the Treaty Oak. That ishis-

tory, soI'dleaveit. I'dalsotakeanacorn fromit

and plant it besidethe oldoak, sothat there isa

replacement. Wealwaysassumethat trees, like

nature, are permanent, and, of course, they're

not. I would leave the farmalone and urgeyou

to risk a push for conservation.

FOREMAN: I would tum it into an environmental

education sitefor the town school system, basi-

cally maintain it as a natural area with trails,

centers, environmental education. Youcould

make the farmthe headquarters, and youcould

employ some people that way.

YARO: Realize, right off, that this isasacred land-

scape. How many Oakdaleans were conceived

in the backseats of Mustangs parked on that

bluff? There are primal memories here. This

place is a shrine. It will be very easy to muck

things up if wearen't careful. Youmust keep the

farm, because that's the vista seen from the

bluff. You've got to manage it. To generate

somemoney and jobs, I

would consider limited

development on the

southend, built inatight

duster tucked into the

woods. It should look

and feel like Oakdale

insteadof sprawl. Then,

adopt new regulations

that requiresimilar land-

conserving patterns of

development throughout

theOakdaleregion.

BOTKIN: If you want to

conserve it, I would

avoid the pitfall that

Central Park smartly

avoided: letting people

develop a little around

the edges. Youmight try

tradingthesouthernland

for additional northern

land, especiallythe land

upriver. Then you can

make a statement about

protecting the forestand

the floodplainupriver.

LOVELOCK: If this were

in Europe, one might

consider "in-filling." In

other words, all develop-

ment wouldhappenw ith-

in the town; the town's

populationdensitywould

be increased in order to spare the wilderness.

POLLAN: But I have to go to atown council meet-

ing tomorrow night and I have to defend my

decision. .

OAKDALE

(URBAN AREA)

YARO: Then you might want to keep your car en-

gine running.

POLLAN: Exactly. So what do I say to the unem-

ployedcarpenter who will askmehowthis deci-

sion will help get him ajob?

FOREMAN: I don't really care what yousayto him.

Because I amgoing to organize people-bird-

watchers, hikers, environmentalists, others-

in such awaythat you will fear them far more

than an unemployed carpenter.

BOTKIN: Dave, don't giveupcompletely on thecar-

penter and hissenseof values. Forexample, the

last uncut stand of virginoak and hickory wood-

lands inNewJ ersey-the Hutcheson Memorial

Forest-was purchased and saved with funds

from the carpenters' union, and it was named

for a former president of the union. Youcan

appeal to higher values, and the carpenters,

FORUM 45

among others, will respond.

POLLAN: Well, I have decided that you guyshave

your heads in the clouds. I amgoing to develop

the entire square mileby selling five-acreplots.

You'vetried to stop me, but everything-peti-

tions, lawsuits, protests-has failed. The politi-

cal process isover. It'sAmerica. It's democracy.

Do you go home now?

FOREMAN: I never go home.

POLLAN: What do you do?

FOREMAN: Conservationists have a fully equipped

toolshed and usethe proper tool for the proper

job at the proper time.

" B y2000, WARME

STATELY OLD T

THEM VULNERA!

HIKERS WILL FIN

AM

FOREMAN: Let's talk.

LOVELOCK: See, if I really felt strongly about this

issue, I would be obliged to act-even at the

risk of losing credibility.

POLLAN: Is there a limit to what you'd do?

FOREMAN: There arecertain issuesI feel sostrongly

about that I will plant my spear in the ground

and stand there, regardless. For example, during

the demonstrations in Oregon to save old-

growth forests, I wasrun down and pushed for a

hundred yards by a truck full of loggers. They

were trying to kill me and I knew it, but I

couldn't get out of the waybecauseI had madea

commitment that I wasgoing

to stand there. My larger

commitment isthat I'mgoing

to be nonviolent toward liv-

ingthings. I amwilling to die

forwhat I believe in. I amnot

willing to k i l l for what I be-

lieve in-although if I were

an Indian in Amazonian Peru

and my land wasbeing invad-

ed by oil companies, I might

use my blowgun or my bow

and arrow. B ut this is a real problem I contin-

uallyrun into with the yippietypewho believes

inrevolution for the hell of it. I'mavery reluc-

tant radical.

URES WILL CAUSE

CKANDMAKE

AND B LIGHTS.

INCREASINGLY

YARO:Are hatchets in your toolshed?

FOREMAN: Lots of things are in there!

POLLAN: And after politics are exhausted?

FOREMAN: Oh, youmight start bypulling upsurvey

stakes. And you might want to engage in some

paper monkey-wrenching, to slowthings down.

YARO: Paper can beone of the most effectivetools.

Youknow, this society can't do things very

quickly, but it is brilliant at slowing things

down.

POLLAN: Suppose Davecalled youthe night before

the bulldozersshowedup. He's planning to pour

something in the gastanks. Will youhelp him?

TURNER:Peopledo what they arebest equipped to

do. I'mnot a politician. My inclination would

be to use art, theater, poetry, and song. The

power of agoodsong, likethe coal miners' strike

songs, is terrific.

B OTKIN: I agreewith Fred. What I bring to the en-

vironmental arena ismyreputation asan objec-

tive scientist who can evaluate the land. To

pour something in a gas tank-

FOREMAN: -grinding compound-

B OTKIN:-would destroy my credibility. We all

must play different roles.

LOVELOCK: Dave, it just so happens that my main

line of work is as an inventor. I can think of a

lot of things I could do to those bulldozers.

46 HARPER'S MAGAZINE I APRIL 1990

YARD: Sometimes, though, wehave to loseaplace

in order to galvanize public attention. Some-

times the most effective way of preventing fu-

ture damage is to let the damage occur. And

record it, publicizeit. The Glen Canyon Damis

one of the most horrible things to occur on this

continent. It's what's known as a cash-register

dam-built for no good reason except to fi-

nance even more pork-barrel programs. Now it

is a symbol and has inspired a conservation

movement across the country.

Speaking for Wolf

POLLAN:B ecause of my brilliant management of

this problem, I have moved on to higher office.

I amPresident of the United States. I amarea l

environmental president, and I want to do

something dramatic. What actions-both po-

litical and symbolic-would you advise me to

take in order to motivate the nation?

TURNER:As I mentioned earlier, I would reform

the tax systemto penalize species loss and en-

courage ecological diversity. And, since the

U.S. Forest Service has done such a rotten job

with the land, it wouldbebetter tosell it to pri-

vate owners with the kind of tax structure that

would encourage them, pridefully and profit-

ably, to care for the land. State control of the

economic systemfailed in Eastern Europe. Why

should state control of the ecosystemwork any

better than private ownership here?

BOTKIN: As long as we thought nature was "one

state," wedidn't need to monitor it. Now that

we know that nature is always changing, we

must track its conditions. We need global-

research institutes-one research center per

continent-to study the atmosphere and the

dynamics of Earth. I would revise the national

park systemsothat the parkswereconnected in

such awaythat natural migrations might occur.

As asymbolic action, I would honor the treaty

with the Sioux, return the Black Hills to them

to run buffalo and manage the ecology. You

could get alot of pressfor this; you'd bethe next

Teddy Roosevelt.

FOREMAN: Let's recognize that 1992 is the SOOth

anniversary of the European economic discov-

ery of America and then seek a new covenant

with the land. As President, you should invite

the leaders of native peoples to the White

House to apologizefor what we've done and to

seek their advice on how to live on Turtle Is-

land. I, too, wouldreturn the Dakota prairie to

the Sioux. Use 1992 as a symbolic time to

launch these initiatives.

To manage the human population, offer ev-

ery woman in the world free access to family

planning, abortion, and sterilization-at home

and abroad. Don't imposeit, just offer it. Final-

ly, announce national goalstocut by50percent

America's consumption of paper, wood, miner-

als, energy, and water by the year 2000.

YARO: I would start by having you roll out of bed

one morning at Pennsylvania Avenue and walk

to Union Station and hop on the Metroliner to

Philadelphia-one of America's first planned

cities. There youwouldannounce a2S-cents-a-

gallon increase intheoil-import duty foreach of

the next ten years. This will bring U.S. oil

prices in line with the rest of the world. With

the revenue you can retire a big chunk of the

national debt and announce anational program

to rebuild the metropolitan transportation

systems.

LOVELOCK: Weare in asimilar position to that of

Europe in 1938. In those daysone knew that a

war waslooming, but nobody had the slightest

ideawhat todo about it. One groupwassaying,

Fight Nazism; another was saying, Disarm.

There wereafewsensible people who prepared

for the war. Well, weareinfor the equivalent of

awar in the next fiveor ten years, and it would

be sensible to prepare people's minds for that.

The destruction of the tropical rain forests

and the greenhouse effect are so serious-

they're not just the doomstories of scientists-

that the consequences will be upon us within

fiveto ten years. They will come in the formof

surprises: storms of vastly greater severity than

anything we'veever experienced before, disrup-

tions in the ozone layer, events for which no

amount of expensive computer simulation could

possibly prepare us. As is the essence of sur-

prises, we can't know what they will be. We

have an enemy out there, and it will play some

dirty tricks and hit uswith some new weapons.

POLLAN: Do wehave to wait for aPearl Harbor be-

fore wecan act?

LOVELOCK: That gets to my suggestion. As Presi-

dent, you should go to Pearl Harbor and give

anationwide televised speech to prepare the

people.

BOTKIN: J im is right. Our projections on global

warming suggest that by the year 2000, wewill

begin to see rapid changes over vast areas. In

parts of the North, weexpect to seestately old

trees beginning to die back. The warmer tem-

perature will make many trees vulnerable to in-

sect attacks and different blights. Hikers will

increasingly find themselves among dead trees.

Loggers will have to choose between harvest-

ing the dead timber and glutting the lumber

and paper industries. And the diebacks will

affect water supply and erosion rates. It's really

overwhelming.

So your policies to curb global warming

should beyoked to symbolic actions in order to

motivate people. For example, I might have the

president create an environmental trail begin-

ning at the front door of the White House, go-

ing out of President's Park, down to the Mall,

into Rock Creek Park, on to the Appalachian

Trail, all the wayto the BlueRidgeMountains.

I've checked this out. It can be done.

TURNER: I ambothered by the model of war. I am

not a scientist, but I gather that there is much

scientific data to the effect that the changes

wrought by human beings in the ecosphere are

still within the rangeof changes that have been

going on anyway. Isn't the climate of the world

on a kind of random wave into which these

changes fit comfortably? I think the war model,

bywhich wetry to get everybody anxious, leads

todespair and toapoint wherepeople act out of

guilt and fear. The motivations of guilt and fear

are asdamaging to one's capacity for creativity

asthey are to sex: If you're in an acute state of

guilt andfear, youwill not beverygoodat sexor

at coming up with good ideas.

I would look for waysto use hope, expecta-

tion, adventure, and curiosity as motivators. I

want to see the destruction of the rain forests

FORUM 47

and theozonelayer and the greenhouse effect as

occasions for international cooperation. Weare

at the beginning of the greatest periodof human

history. Tomotivate usin apositive way, I have

two suggestions.

First, let usrecognizethat nature isaprocess

of reproduction, of inaccurate self-copying-a

seriesof "flaws" that account for evolution. And

that human reproductions of nature arenot sub-

stitutes for authentic nature but are authentic

nature. Humankind's efforts areacontinuation

and extension of that reproduction, evolution,

and improvement. Since only about 5 percent

of the genetic material of any species is ex-

pressed, the other 95 percent is an archive of

evolutionary history. Thus wemaybeable tore-

construct lost species. Weshould do so, and we

should think of these efforts aspositive accom-

plishments. We are promoting nature because

weare nature. Wearethe leading edge, the sen-

sitive tip, the cambium of nature. And weare

charged with its promotion.

Second, this world, this universe, isachaot-

ic, self-organizing, dissipative systemthat never

repeats itself. If webelieve that wemust main-

tain nature at a particular point of arcadian or

pastoral perfection, then we are doomed. We

must see ourselves as part of a universe whose

divine drama has only begun. So let us recover

our ritual senseof evolution. I wouldestablish a

Presidential Prairie and create two festival days

in the year. The first would be seed-collecting

day for the president, his family, kids, the Girl

Scouts-all of us-to goto oldgraveyards, rail-

road rights-of-way, and the likeand collect the

seedsto beplanted inthe prairie. Since prairies

have to beburned, the second festival wouldbe

in the spring, and there would be agreat burn-

ing. It would be a ritual performance, and TV

would be there. Youwould see it. It would be

photogenic. It would begreat footage. It would

be a beautiful thing.

LOVELOCK: Fred, I just want to return to my war-

time language. I remember 1938 very clearly,

andit wasnot atimeof despair at all. The threat

of war stirs a feeling of adventure. If you had

lived in London then, you wouldhave found it

was a very pleasant place. The threat of war

didn't cause misery or a lack of creativity. Art

and writing flourished in those heady times. Far

more paralyzing than the threat of war is the

foolish suburban contentment in which many

people now languish.

YARO: Since this is the decade of turning ICBMs

into plowshares, I propose two post-Cold War

initiatives for the president. Make "America

the Beautiful" the nation's anthem. Instead of

contemplating the "rockets' red glare," let's

reflect on "thine alabaster cities" and "purple

48 HARPER'S MAGAZINE iAPRIL 1990

mountain majesties." Then let's reclaim that

song's images and vistas by bringing home the

300,000 soldiers from Europe and dedicating

the resulting savings to repairing our lands and

cities.

BOTKIN: And let's tum our coastal military bases

into maritime research centers and convert our

land bases into environmental stations.

LOVELOCK: As we make these changes, we

shouldn't neglect technological advances. Shell

Oil in Europe, for example, has a scheme for

burning coal inpureoxygenthat eliminates pol-

lution. I amnot one of those environmentalists

who sayweshould goback to the land and bum

candles to light our homes. It's like passengers

on a ship deciding they loathe ironware tech-

nologyandjumping off the ship to swimthe rest

of the way.

POLLAN: Dave, areyouasconfident about our abi4i-

ty to solve our problems?

FOREMAN: I guess I disagree with everybody. We

are foolish to believe that all our problems are

solvable, especially by technology or sociology.

The technological fix often creates twice as

many problems asit solves. Weneed fewer solu-

tions and more humility. Our environmental

problems originate in the hubris of imagining

ourselves as the central nervous systemor the

brain of nature. We're not the brain, weare a

cancer on nature.

The Oneida Indians tell an old story about

the tribe discovering anew, perfect place. After

they moved, they found that the area had many

wolves. They considered slaughtering the

wolvesbut then thought, What kind of people

would we become if we killed them? They

stayed, but, to deal with this problem in the fu-

ture, they appointed one man to attend the

council meetings and "speak for wolf" Wemust

overcome our hubris and learn to speak for wolf

TURNER: There may be limits to technology, but

I've seen blackened and polluted sections' of

England made rich with life. Technology isnot

necessarily bad, andneither arewe. I deeply ob-

ject to the metaphor of humankind asacancer.

My parable, Dave, is that early on, when life

first appeared, the crystals and chemical organ-

ismsmust havethought, What isthis thing that

keeps reproducing itself? It keeps on changing.

It's messing up the atmosphere. It keeps trans-

forming itself. It's full of hubris, life. For what is

lifebut acancer upon the purity of the inorgan-

ic? If weare acancer, if lifeis acancer, then I

amfor it. The nervous systemisaglorious can-

cer that has evolved, and I stand with it. I am

that cancer.

I-

FOREMAN: And I amthe antibody.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- (And Themed Math Games) : Habitats With STEM ActivitiesDocument28 pages(And Themed Math Games) : Habitats With STEM ActivitiesLydia HouNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Medicinal Plants of BalochistanDocument39 pagesMedicinal Plants of Balochistanfatmanscooby86% (7)

- Urban Nature and Human DesignDocument20 pagesUrban Nature and Human DesignlulugovindaNo ratings yet

- San Lorenzo Ruiz Clup VolonethreeDocument269 pagesSan Lorenzo Ruiz Clup VolonethreearvinNo ratings yet

- Sarkis, Hashim TheWorldAccordingToArchitectureDocument8 pagesSarkis, Hashim TheWorldAccordingToArchitecturelulugovindaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae Charles WaldheimDocument6 pagesCurriculum Vitae Charles WaldheimlulugovindaNo ratings yet

- Spatial Variability in Palustrine WetlandsDocument9 pagesSpatial Variability in Palustrine WetlandslulugovindaNo ratings yet

- Olin, Laurie. Trees and The Getty What The Trees TryDocument8 pagesOlin, Laurie. Trees and The Getty What The Trees TrylulugovindaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument53 pagesUntitledlulugovindaNo ratings yet

- Instructor: Lance M. Neckar, Professor: Istory of Andscape RchitectureDocument18 pagesInstructor: Lance M. Neckar, Professor: Istory of Andscape RchitecturelulugovindaNo ratings yet

- Darwin and The World'S First Ecological ExperimentDocument2 pagesDarwin and The World'S First Ecological ExperimentlulugovindaNo ratings yet

- Take2HoursOfPine&CallMeInTheMorning OutsideMagazineDocument9 pagesTake2HoursOfPine&CallMeInTheMorning OutsideMagazinelulugovindaNo ratings yet

- Epifitas Da Pedra AzulDocument13 pagesEpifitas Da Pedra AzulAndre AssisNo ratings yet

- Silviculture of Indian TreesDocument86 pagesSilviculture of Indian Treessneha0% (1)

- Forest EcosystemDocument16 pagesForest EcosystemThavakka PnmNo ratings yet

- All Tests in This Single FileDocument1,944 pagesAll Tests in This Single FileMohammed ShukkurNo ratings yet

- 12 - Future of Mangrove Ecosystems To 2025 Pp. 172-187Document17 pages12 - Future of Mangrove Ecosystems To 2025 Pp. 172-187Soma GhoshNo ratings yet

- (Bongers 1988) Structure and Floristic Composition of The Lowland Rain Forest of Los Tuxtlas, MexicoDocument26 pages(Bongers 1988) Structure and Floristic Composition of The Lowland Rain Forest of Los Tuxtlas, MexicoMarcelo MenezesNo ratings yet

- SOAL PAS B. Inggris Kls X Ganjil 2020Document14 pagesSOAL PAS B. Inggris Kls X Ganjil 2020taufan Adi SaputroNo ratings yet

- Bus 378 Business Environment: Group 5Document16 pagesBus 378 Business Environment: Group 5Phùng Gia NgọcNo ratings yet

- 2018 Climate-Smart Sustainable Agriculture in Low-To - Intermediate Shade AgroforestsDocument6 pages2018 Climate-Smart Sustainable Agriculture in Low-To - Intermediate Shade AgroforestsmiguelNo ratings yet

- Pixel - and Site-Based Calibration and Validation Methods For Evaluating Supervides Classification of Remote Sensed Data PDFDocument10 pagesPixel - and Site-Based Calibration and Validation Methods For Evaluating Supervides Classification of Remote Sensed Data PDFjorgederas82No ratings yet

- FINAL Biodiversity Baseline KNI-Pomalaa - 06!03!2023Document88 pagesFINAL Biodiversity Baseline KNI-Pomalaa - 06!03!2023lee alexphoneNo ratings yet

- Alberdi2017 PBDocument9 pagesAlberdi2017 PBTiara NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Types of ForestsDocument5 pagesTypes of ForestsNamitNo ratings yet

- Ecology and Human Organization On The Great PlainsDocument223 pagesEcology and Human Organization On The Great PlainsFederico PérezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Review QuestionDocument2 pagesChapter 6 Review QuestionThithi24No ratings yet

- Protective Function of Forest Resources Background Paper To The Kotka V Expert ConsultationDocument8 pagesProtective Function of Forest Resources Background Paper To The Kotka V Expert ConsultationHima BinduNo ratings yet

- Final Report Machaze WildlifeDocument78 pagesFinal Report Machaze WildlifeandreaghiurghiNo ratings yet

- Forest EcologyDocument17 pagesForest EcologyHamed MemarianNo ratings yet

- 3dea2029ed9eb115091e9ea026cbba8fDocument3 pages3dea2029ed9eb115091e9ea026cbba8fJamie Cea100% (1)

- Type of Outdoor EnvironmentDocument2 pagesType of Outdoor Environmentapi-518916033No ratings yet

- WHO Guidelines Vegetation Fires 1999 Background PapersDocument481 pagesWHO Guidelines Vegetation Fires 1999 Background PapersridaagustinaaNo ratings yet

- Forestry Syllabus Decoded Rev 2Document1 pageForestry Syllabus Decoded Rev 2Sagar PawarNo ratings yet

- Habtamu Kenea MSC ThesisDocument89 pagesHabtamu Kenea MSC Thesismuzayan abdeNo ratings yet

- Forestry ARD NotesDocument14 pagesForestry ARD Notessankalp agrawal0% (1)

- Integrated Flood Analysis System (IFAS) Integrated Flood Analysis System (IFAS)Document21 pagesIntegrated Flood Analysis System (IFAS) Integrated Flood Analysis System (IFAS)Dio PermanaNo ratings yet

- Environmental ScienceDocument9 pagesEnvironmental ScienceRaphael Leandro GuillermoNo ratings yet