Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EN

Uploaded by

reacharunkOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EN

Uploaded by

reacharunkCopyright:

Available Formats

PREFACE.

ix

lu

all matters of importance, in which the works of previous writers have

been

used, the sources have been indicated, so that reference to the originals

may be made. Upon the celebrated work of Eondelet above mentioned, on

many learned articles in the Encyclopedie Methodique, and on the works o<

Durand and other esteemed authors, large contributions have been levied;

but these citations, it will be observed, appear for the first time in an

EngUsh dress. In that part of the work which treats of the doctrine of arches,

the chief materials, it will be seen, have been borrowed from Eondelet, whose

views the author has adopted in preference to those he himself gave to the

world many years ago, in a work which passed through several editions.

Again, in the section on shadows, the author has not used his oAvn treatise

on Sciography. In the one case, he is not ashamed to confess his inferiority

in so important a branch of the architect's studies; and in the other, he

trusts that matured experience has enabled him to treat the subject in a form

likely to be more extensively useful than that of treading in his former steps.

The sciences of which an architect should be cognisant are enumerated by

Vitruvius at some length in the opening chapter of his first book. They are,

jjerhaps, a little too much swelled, though the Koman in some measure

qualifies the extent to which he would have them carried.

*'

For," he ob-

serves,

"

in such a variety of matters " (the different arts and sciences)

"

it

cannot be supposed that the same person can aixive at excellence in each."

And again :

"

That architect is sufficiently educated Avhose general knowledge

enables him to give his opinion on any branch when required to do so. Those

unto whom nature hath been so bountiful that they are at once geometricians,

astronomers, musicians, and skilled in many other arts, go beyond what is

required by the architect, and may be properly called mathematicians in the

extended sense of that word." Pythius, the architect of the temple of INIinerva

at Priene, differed, however, from the Augustan architect, inasmuch as he

considered it absolutely requisite for an architect to have as accurate a know-

ledge of all the arts and sciences as is I'arely acqmred even by a professor devoted

exclusively to one.

In a work whose object is to compress within a comparatively

restricted

space so vast a body of information as is implied in an account of what is

known of historical, theoretical, and practical architecture, it is of the highest

importance to preserve a distinct and precise arrangement of the subjects, so

that they may be presented to the reader in consistent order and imity.

Without order and method, indeed, the work, though filled with a large and

valuable stock of information, would be but an useless mass of knowledge.

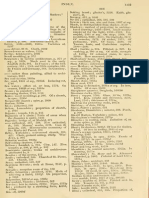

In treating the subjects in detail, the alphabet has not been made to perform

the function of an index, except in the glossary of the technical terms, which

partly serves at the same time the purpose of a dictionary, and that of an

index to the principal subjects noticed in the work. The following is a

synoptical view of its contents, exhibiting its different parts, and the mode in

whi(!h they arise from and are dependent on each other.

[-4

List of the Conteiita teas here inserted.'\

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- React NativeDocument100 pagesReact NativeMohammed Zeeshan0% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Handy Man's Plywood ProjectsDocument148 pagesHandy Man's Plywood Projectsironicsmurf100% (7)

- 2310-How To Build An Efficient SAP Application Landscape Based On Your Business RequirementDocument50 pages2310-How To Build An Efficient SAP Application Landscape Based On Your Business RequirementkrismmmmNo ratings yet

- 2-BAIRD George Criticality and Its DiscontentsDocument6 pages2-BAIRD George Criticality and Its Discontentsreza56mNo ratings yet

- Cholistan Desert Architecture SynpsisDocument5 pagesCholistan Desert Architecture SynpsisAbdulwahab WahabNo ratings yet

- Types of Urban DesignDocument12 pagesTypes of Urban DesignSumitNo ratings yet

- Greenhouse Structures and Design (Kacira) 2012Document9 pagesGreenhouse Structures and Design (Kacira) 2012dindev_gmailNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocument65 pagesSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1463)Document1 pageEn (1463)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Emergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014Document2 pagesEmergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocument65 pagesSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1461)Document1 pageEn (1461)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- PZU EDUKACJA INSURANCE TERMSDocument19 pagesPZU EDUKACJA INSURANCE TERMSreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1464)Document1 pageEn (1464)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- NameDocument2 pagesNamereacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1462)Document1 pageEn (1462)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1457)Document1 pageEn (1457)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1459)Document1 pageEn (1459)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1458)Document1 pageEn (1458)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocument1 pageAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1460)Document1 pageEn (1460)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1454)Document1 pageEn (1454)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1455)Document1 pageEn (1455)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1456)Document1 pageEn (1456)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocument1 pageMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1390)Document1 pageEn (1390)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1453)Document1 pageEn (1453)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1452)Document1 pageEn (1452)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1450)Document1 pageEn (1450)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1451)Document1 pageEn (1451)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1389)Document1 pageEn (1389)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1387)Document1 pageEn (1387)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1388)Document1 pageEn (1388)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- MRTS25 Steel Reinforced Precast Concrete PipesDocument23 pagesMRTS25 Steel Reinforced Precast Concrete Pipeswhutton11No ratings yet

- Ba WW Deluxe Excellent Prestige Premium Landhaus 2012 en PDFDocument157 pagesBa WW Deluxe Excellent Prestige Premium Landhaus 2012 en PDFCatalin BejanNo ratings yet

- WRF InstallationDocument4 pagesWRF InstallationiperivNo ratings yet

- Charles CorreaDocument43 pagesCharles CorreaPrashant ChavanNo ratings yet

- Gym - Yangon - Ac Design - 17TH July 2020Document2 pagesGym - Yangon - Ac Design - 17TH July 2020Hnin PwintNo ratings yet

- 1925 BBS ContentsDocument3 pages1925 BBS ContentsAnnaNo ratings yet

- QW757 Repaint KitDocument13 pagesQW757 Repaint KitLuís Pedro MelimNo ratings yet

- CCNA Security v2 Chapter - 3Document6 pagesCCNA Security v2 Chapter - 3Frikisito80No ratings yet

- How To Submit JCL From CICS ProgramDocument3 pagesHow To Submit JCL From CICS ProgramMainframe for everyone100% (2)

- Living in A Network Centric WorldDocument10 pagesLiving in A Network Centric WorldAngel FelixNo ratings yet

- p013668 - Why Are Customers Choosing Power Systems Instead of x86Document50 pagesp013668 - Why Are Customers Choosing Power Systems Instead of x86Bewqetu SewMehoneNo ratings yet

- CCOON N S TSRTU R C TUI OCNT I O N USING AT89C52 TEMPERATURE INDICATORDocument6 pagesCCOON N S TSRTU R C TUI OCNT I O N USING AT89C52 TEMPERATURE INDICATORVipan Sharma100% (2)

- The Leela PalaceDocument22 pagesThe Leela Palaceajji josyulaNo ratings yet

- IT 205 Chapter 1: Introduction to Integrative Programming and TechnologiesDocument42 pagesIT 205 Chapter 1: Introduction to Integrative Programming and TechnologiesAaron Jude Pael100% (2)

- THE BOOK OF Lumber Slied Construction - by MET L. SALEYDocument184 pagesTHE BOOK OF Lumber Slied Construction - by MET L. SALEYxumontyNo ratings yet

- C.9. Design Considerations For Economical FormworkDocument10 pagesC.9. Design Considerations For Economical FormworkRsjBugtongNo ratings yet

- Conf2015 MGough MalwareArchaelogy SecurityCompliance FindingAdvnacedAttacksAnd PDFDocument62 pagesConf2015 MGough MalwareArchaelogy SecurityCompliance FindingAdvnacedAttacksAnd PDFVangelis MitakidisNo ratings yet

- The Sloop's Log Spring 2011Document20 pagesThe Sloop's Log Spring 2011Chebeague Island Historical SocietyNo ratings yet

- Atf 16 V 8Document19 pagesAtf 16 V 8Mauricio RosasNo ratings yet

- At Mega 8535Document275 pagesAt Mega 8535itmyNo ratings yet

- PP Vivo 2009 ENDocument12 pagesPP Vivo 2009 ENSara TaraNo ratings yet

- K8M8Ms: Cpu 800Mhz FSB /agp 8X /serial Ata /Ddr400 /6-Ch Audio SolutionDocument1 pageK8M8Ms: Cpu 800Mhz FSB /agp 8X /serial Ata /Ddr400 /6-Ch Audio SolutionMaria MassanetNo ratings yet

- DSR Vol. 1-1Document234 pagesDSR Vol. 1-1Charan Electricals100% (2)