Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vulpe Radu Columna Lui Traian

Uploaded by

Constantin IrimiaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vulpe Radu Columna Lui Traian

Uploaded by

Constantin IrimiaCopyright:

Available Formats

COLUMNA LUI TRAIAN

TRAJAN S COLUMN

www.cimec.ro

Coperta / Front Cover: Columna lui Traian / Trajans Column

Coperta / Back Cover: Alegoria victoriei / The Allegory of Victory

www.cimec.ro

RADU VUL PE

COLUMNA LUI TRAIAN

TRAJAN S COLUMN

cI MeC

2002

www.cimec.ro

Aceast publicaie apare cu sprijinul financiar al Ministerului Culturii i Cultelor

This volume is printed with the financial support of the Ministry of Culture and Religious Affairs

Ediia I (1988) ngrijit de / The first edition edited by: Ecaterina Dunreanu-Vulpe

Ediia a II-a ngrijit de / The second edition revised by: Magdalena Vulpe

Postfa / Afterword: Lucia eposu-Marinescu

Fotografii: George Dumitriu (dup mulajele Columnei lui Traian aflate n lapidarium-ul

Muzeului Naional de Istorie a Romniei)

Photos: George Dumitriu (after the casts of Trajans Column displayed in the lapidarium of

The National History Museum of Romania)

Traducere n limba englez / English version: Anca Doina Cornaciu

Copyright Alexandru Vulpe (text) i cIMeC 2002

Editori / Editors: Corina Bor, Irina Oberlnder-Trnoveanu

Redactor: Mihai Dima

Procesare de imagini, tehnoredactare i machetare / Image processing and desktop publishing: Tudor Stnic

Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naionale a Romniei

VULPE, RADU

Columna lui Traian = Trajans Column / Radu Vulpe ;

Trad.: Anca Doina Cornaciu. Bucureti : CIMEC, 2002

p. 312; cm. 23,5 x 31,5 (Restitutio)

I. Cornaciu, Anca Doina (trad.)

725.942(450 Roma)

ISBN 973-85887-6-6

cIMeC Institutul de Memorie Cultural

Piaa Presei Libere 1, C.P. 33-90, Tel/fax: (021) 224 37 42

713411 Bucureti e-mail: cimec@cimec.ro

http://www.cimec.ro

Volum tiprit de / Printed by: S.C. DAIM P.H. s.r.l.

www.cimec.ro

Roma: Columna lui Traian

foto: Mircea Victor Angelescu

Rome: Trajans Column

Roma imperial n timpul domniei lui Constantin cel Mare reconstituire (Museo della

Civilt Romana Roma); foto: Mircea Victor Angelescu

Imperial Rome during the reign of Constantine the Great reconstitution

www.cimec.ro

Roma: Columna lui Traian noaptea

foto: Mircea Victor Angelescu

Rome: Trajans Column by night

Columna lui Traian

detalii

Trajans Column

Details

www.cimec.ro

Drobeta-Turnu Severin: 1. Piciorul podului lui Traian, 2. Castrul roman, 3. Muzeul

(vedere aerian); foto: arhiva INMI

Drobeta-Turnu Severin: 1. The remains of the Trajans Bridge, 2. The Roman

camp, 3. The Museum (aerial view)

Drobeta-Turnu Severin: piciorul podului lui Traian

Drobeta-Turnu Severin: The remains of the Trajans Bridge

Podul de la Drobeta reconstituire (Museo della Civilt Romana Roma)

The Trajans Bridge from Drobeta reconstitution

www.cimec.ro

Tropaeum Traiani monumentul triumfal (reconstituire)

foto: Ioana Bogdan Ctniciu

Tropaeum Traiani the triumphal monument (reconstitution)

Sarmizegetusa Regia (vedere aerian)

foto: Eugen Pescaru

Sarmizegetusa Regia (aerial view)

www.cimec.ro

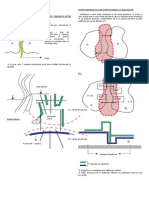

Localitile din Dacia prin care

au trecut armatele romane

n anii 101-102 i 105-106

The localities in Dacia Roman

armies passed through

in A.D. 101-102 and 105-106

www.cimec.ro

inuturile parcurse de Traian n drum spre Dacia n anul 105 / Trajans route from Rome to Dacia A.D. 105

www.cimec.ro

11

CUVNT NAI NTE

( l a edi i a I )

la identificarea Piroboridavei n staiunea geto-dac de la

Poiana (jud. Galai), apoi despre localizarea Angustiei la

Brecu (jud. Covasna), a Argedavei la Popeti (jud. Giurgiu)

etc. Tot prin aceste metode a fost atacat i problema

interpretrii valului de pmnt din sudul Moldovei i

identificarea lui cu ntriturile construite de Atanarich,

menionate n textele antice. Un alt exemplu este studiul n

care se stabilete relaia ntre strmutarea unui numr mare

de gei la sud de Dunre n primii ani ai erei noastre, eveniment

narat de Strabo, i sfritul mai multor aezri getice din

Cmpia Romn. n sfrit, trebuie amintit i interpretarea

culturii arheologice Poieneti - Lukaevka, din secolele II - I

.e.n., prin ptrunderea i aezarea bastarnilor n aria

respectiv (centrul i nordul Moldovei), printre autohtonii

daco-gei. O serie de lucrri n care autorul i-a dovedit

capacitatea de a folosi n mod judicios i cu bune rezultate

critica de text i informaia arheologic au aprut n Studia

Thracologica (Bucureti, 1976).

Dac la nclinaia, att de timpuriu manifestat, de a

cunoate direct mediul geografic implicat n cercetrile sale

adugm informaia c una din lecturile preferate ale lui Radu

Vulpe o constituiau descrierile cu amnunte strategice ale

marilor btlii ale istoriei, nelegem mai bine de ce Columna

Traian oferea un cmp ideal de realizare a calitilor,

metodelor i preocuprilor sale, dobndite dup o lung i

rodnic via de cercetare.

Convingerea de totdeauna a lui Radu Vulpe c relieful

Columnei este o nregistrare fidel a succesiunii evenimentelor

prezentate n Comentariile scrise de Traian nsui despre cele

dou rzboaie mpotriva dacilor l-a ndemnat s descifreze

printr-o parial nou interpretare mesajul acestei opere,

pierdute ca document literar, dar conservate peste veacuri ca

suit de imagini n basorelief. ncepnd din anul 1963, autorul

a consacrat reliefului Columnei mai multe studii speciale, ca

cel despre burii aliai ai lui Decebal n primul rzboi dacic

sau cel despre Cassius Dio i campania lui Traian n Moesia

Inferioar .a.

Aducerea n ar, n iunie 1967, a mulajelor reliefului

Columnei i-a dat lui Radu Vulpe posibilitatea examinrii

directe a scenelor de pe monument. Astfel s-a nscut ideea

Radu Vulpe a fost o personalitate bine cunoscut tuturor

celor interesai de istoria veche a rii nostre, fie ca specialiti

n materie, fie ca oameni de cultur cu cele mai diferite

formaii. Evocrile nsoite de date bio-bibliografice publicate

cu puini ani n urm, la dispariia sa, au dovedit-o cu

prisosin (Dacia, NS, XXVII, 1983, p. 199 i urm.; Thraco-

Dacica, IV, 1983, 1-2, p. 158 i urm.; Studii clasice, XXI,

1983, p. 199 i urm.; Studii i cercetri de istortie veche i

arheologie, 34, 1983, 1, p. 175 i urm.; vezi i Dacia, NS,

XV, 1971, p. 5 i urm). Nu este aici locul s reiau sau s

sintetizez cele scrise atunci; consider ns necesare unele

precizri, menite s arunce o lumin asupra genezei i

structurii acestei cri.

Viaa lui Radu Vulpe a fost dominat de pasiunea -

unic i statornic - pentru istorie. colar n clasele primare,

umbla pe valurile romane din Dobrogea, ncercnd s le

ptrund tainele. Elev la liceu, refugiat n timpul rzboiului

n tabra de cercetai din Moldova, a fost vzut de colegi

(Dan Alecu, O coal n aer liber, Constana, 1927) cum, fiind

de planton ntr-o noapte geroas, citea la lumina felinarului

De bello Gallico. n studenie, a parcurs, pas cu pas, malurile

apelor din Cmpia Romn, pentru a descoperi urme ale

anticelor aezri omeneti.

Colaborator al magistrului su Vasile Prvan, mai

trziu conductor a numeroase antiere arheologice, Radu

Vulpe a fost i a rmas, n primul rnd, istoric. Pentru el

arheologia era menit s suplineasc i s ntregeasc

informaia furnizat de documentele literare. mbinarea celor

dou ci de cercetare, cu metodele lor proprii, urmrea un

scop unic: reconstituirea evenimentului prin vitalizarea

datelor seci, judecate n adncime pn la descoperirea

structurii istorice. Aa a neles s abordeze probleme din

epoca neolitic pn n cea romano-bizantin.

Bun cunosctor al izvoarelor literare ale istoriei noastre

vechi i, n acelai timp, arheolog cu o ndelung experien

ctigat prin explorarea a numeroase obiective, printre care

au precumpnit cele de epoc geto-dac, Radu Vulpe a reuit,

n multe cazuri, s ofere soluii originale n tlmcirea unor

informaii fragmentare i controversate. Pentru a ilustra cele

afirmate prin cteva exemple, amintesc lucrrile referitoare

www.cimec.ro

12

Columna lui Traian

unei lucrri generale, care s cuprind att descrierea, ct

i reanalizarea imaginilor sculptate, n primul rnd din

punctul de vedere al sensului istoric. n acelai timp, el s-a

adresat i publicului larg, printr-o serie de articole aprute

n revistele Viaa Militar, Albina, Magazin istoric etc., n

care i prezenta, n parte, propriile sale interpretri. Pentru

a lmuri unele probleme legate de traseele urmate de armatele

romane n Dacia, autorul s-a deplasat n zonele unde s-au

desfurat ostilitile i a studiat la faa locului terenul, n

pofida greutilor inerente unei vrste naintate. i-a

consolidat astfel prerile prin cercetarea aprofundat a

topografiei, fapt care confer interpretrilor propuse o

temeinicie indiscutabil.

Autorul a dorit ca lucrarea de fa s se adreseze, n

primul rnd, cititorilor cu pregtiri diferite, spre a satisface

interesul mereu viu fa de acest monument de importan

primordial pentru istoria veche a patriei noastre. Nu e mai

puin adevrat c specialitii pot gsi, la rndul lor, sugestii

preioase pentru descifrarea scenelor controversate nc sau

ambigue. Radu Vulpe a procedat la descrierea i analizarea

reliefului n ordinea desfurrii scenelor. Prezentarea ampl

a primului rzboi dacic i descrierea mai succint a celui de

al doilea rzboi - aparent o disproporie - i au explicaia, n

mare parte, n grija autorului de a evita cu orice pre ipoteze

riscante i speculaii asupra evenimentelor legate de cel de

al doilea rzboi, despre care sursele antice dau puine detalii.

Se cuvine precizat ns i faptul c partea final a fost alctuit

n ultimele luni ale vieii sale, ncheierea fiind scris n mod

precipitat, chiar n noiembrie 1982, cu puine zile naintea

sfritului survenit fulgertor.

Nu ncape nici o ndoial c, dac i-ar fi fost cu putin,

Radu Vulpe ar fi procedat el nsui la o revizie a ntregului

manuscris i ar fi insistat mai mult n descrierile scenelor

celui de al doilea rzboi. Mi-a revenit mie sarcina de a revedea

tot textul, eliminnd o serie de repetiii n succesiunea

descrierilor i adugnd o list a bibliografiei utilizate de

autor n redactarea acestei lucrri; nu este deci o bibliografie

exhaustiv asupra Columnei. Am ntocmit, de asemenea, un

glosar coninnd termeni de specialitate, mai puin familiari

marelui public. Pentru ilustrarea textului de fa au fost

reproduse planele publicate de Conrad Cichorius (Die Re-

liefs der Trajanssule, Berlin - Leipzig, 1896 - 1900), la care,

datorit procedeului fotografic aplicat, s-a evitat deformarea

imaginilor provocat de curbura coloanei. Am anexat la volum

i dou hri, cu localitile citate n text, pentru o mai uoar

urmrire a itinerarelor lui Traian spre i n Dacia.

ECATERINA DUNREANU-VULPE

Cuvnt nainte

www.cimec.ro

13

COLUMNA TRAI AN I SEMNI FI CAI A SA PENTRU

I STORI A POPORULUI ROMN

mpratului, de peste 6 m nlime, turnat n bronz i poleit

cu aur. Mai trziu, urna sa funerar, de aur, avea s fie depus

n interiorul piedestalului paralelipipedic, care msura cam cte

5 1/2 m n nlime i de fiecare latur. Piedestalul era ornat n

exterior cu reliefuri reprezentnd armele luate de la daci. Pe

una din feele sale se deschidea o u prin care se ptrundea n

interior, de unde, pe o scar spiral, ntocmai ca ntr-un mina-

ret musulman de azi, se putea urca nuntrul Columnei pn n

vrf. Din loc n loc, n peretele Columnei era practicat cte o

ferestruic pentru a lsa s rzbat lumina zilei.

Pe faa principal a piedestalului, deasupra uii

menionate, se vede o inscripie din care reiese c acest monu-

ment a fost executat n intenia de-a aminti, prin lungimea sa

vertical nlimea colinei spate pentru nivelarea Forului lui

Traian. Textul inscripiei este urmtorul: Senatus Populusque

Romanus Imperatori Caesari Divi Nervae filio Nervae

Traiano Augusto Germanico, Dacico, Pontifici Maximo,

tribunicia potestate XVII, imperatori VI consuli VI, Patri

Patriae, ad declarandum quantae altitudineis mons et locus

tantis operibus sit egestus, adic Senatul i Poporul roman,

Ampratului Caesar, fiul divinului Nerva, lui Nerva Traian

Augustul, nvingtorului germanilor, nvingtorului dacilor,

marelui preot, avnd pentru a aptisprezecea oar puterea de

tribun al plebei, fiind salutat a asea oar ca imperator (cap al

armatei), deinnd a asea oar demnitatea de consul, printelui

patriei (i dedic acest monument) spre a se arta de la ce

nlime s-au excavat, cu atta trud, muntele i locul de aici.

Un martor de nivel i atta tot! Nici un cuvnt despre

glorioasele fapte de arme figurate pe relief, nici o aluzie la

vreun rol funerar destinat piedestalului. Dup titlurile

mpratului precizate n cifre, inscripia dateaz din perioada

cuprins ntre 10 decembrie 112 i 10 decembrie 113. Prin

urmare, n acel an cnd Senatul a decretat inaugurarea Forului

lui Traian, nimeni nu se gndea c mreaa Column ar putea

servi i la altceva dect ca s aminteasc nlimea de 40 m a

unui deal disprut. Celelalte semnificaii ca monument

comemorativ al rzboaielor dacice i ca monument funerar al

mpratului eponim i-au fost date ulterior, pe rnd.

La nceput, Columna, cu dimensiunile sale enorme i

cu albeaa monoton i orbitoare a marmurei din care era

Dacia fusese cucerit.

Cu imensele tezaure ale lui Decebal, mpratul Traian

a hotrt s druiasc Romei un Forum Ulpium, care s

ntreac n ntindere i n strlucire toate celelalte foruri ale

urbei. Un for era o pia unde se desfura cea mai mare parte

din viaa unui ora, cu diverse manifestri politice, adminis-

trative i judiciare, cu tranzacii comerciale, cu ntlniri

particulare de tot felul. De jur-mprejur, piaa era mpodobit

cu statui i edificii somptuoase. Din cauza creterii enorme a

populaiei din Roma, vechiul Forum Romanum din epoca

republican nu mai era suficient, aa c s-a simit nevoia s i

se adauge noi piee largi i frumoase, care, create succesiv de

Iulius Caesar, de August, de Vespasian, de Nerva, au ajuns s

acopere tot spaiul plan disponibil dintre cele apte coline.

Pentru noul su for, lui Traian nu-i mai rmnea dect soluia

de a rade un pinten de deal stncos ce se prelungea din Quirinal

spre Capitoliu. Cu mna de lucru a miilor de sclavi, n rndul

crora se numrau, desigur, i foarte muli captivi daci, aceast

munc imens a fost dus la capt. Dup calculele fcute,

peste opt sute cincizeci de mii de metri cubi de piatr i pmnt

au fost spai i transportai n alt parte a oraului. Pe terenul

astfel nivelat s-a construit, prin iscusina vestitului arhitect

Apollodor din Damasc, cel mai mare dintre forurile

imperiale, egalndu-le ca spaiu pe toate celelalte la un loc

i depindu-le mult prin bogia i amploarea cldirilor

dimprejur, printre care se impuneau ateniei, n primul rnd,

dou vaste complexe semicirculare numite exedrae, o uria

basilica avnd la extremiti cte o mare absid, dou biblioteci

(una pentru volume latine, alta pentru cele greceti) i un arc

de triumf. ntre cele dou biblioteci a fost nlat un monu-

ment de un aspect cu totul original, constnd dintr-o enorm

coloan izolat, n stil doric, sprijinit pe un piedestal

paralelipipedic i msurnd o nlime total de circa 40 m,

cu un diametru care abia trecea de 3 m n medie, ceea ce i

ddea un profil svelt.

Este Columna Traian, monument de marmur care se

pstreaz pn azi, mpodobit cu un lung relief sculptat de jur-

mprejur n form de band spiral cu scene reprezentnd

desfurarea rzboaielor dacice ale lui Traian. Deasupra

Columnei, peste capitelul su doric, se ridica statuia enorm a

www.cimec.ro

14

Columna lui Traian Columna Traian i semnificaia sa pentru istoria poporului romn

construit, va fi produs o impresie neplcut. Se simea nevoia

unui element decorativ care s nvioreze imensa suprafa

neted a fusului cilindric al coloanei. S-ar fi putut recurge,

firete, la canelurile inerente ordinului doric, dar de la nceput

au fost omise, deoarece pe o nlime att de mare aceast

repetiie de simple jgheaburi verticale paralele ar fi fost de un

efect i mai disgraios n contextul celorlalte edificii ale

Forului. Iar nlocuirea canelurilor cu motive clasice, de

inspiraie vegetal ori geometric, n-ar fi fost mai fericit. i

atunci, probabil, sirianului Apollodor din Damasc, obinuit

din patria sa oriental cu tradiia reprezentrilor istorice, i-a

venit ideea de a folosi ntinsa suprafa cilindric a Columnei

pentru sculptarea n relief a celor dou rzboaie dacice ale lui

Traian. Varietatea scenelor i a aciunilor unor nenumrate

figuri umane era de natur s dea monumentului o frumusee

atractiv, care era ntrit i prin pictur, frecvent obinuit

n sculptura antic. Culorile, fiind fcute din pulberi de pmnt

cu ap, fr nici o substan fixativ, au disprut de atunci

ncoace fr urm, dar multe particulariti ale reliefului

dovedesc c artistul le pusese la contribuie cu prisosin. O

serie de amnunte privitoare la dispoziia i execuia imaginilor

indic, dup cum a observat Giuseppe Lugli, c relieful a fost

cioplit, cel puin n parte, cu ajutorul schelelor. Se explic

astfel de ce inscripia menionat, pus pe monument nc de

la nceputul construciei este lipsit de orice aluzie la subiectul

reliefului.

i mai puin se putea prevedea, la data acelei inscripii,

n 113, c monumentul avea s capete un caracter funerar.

Dei Traian atinsese vrsta de 65 de ani, moartea sa, n vara

anului 117, departe, n Cilicia, n plin desfurare a rzboiului

partic, i-a surprins oarecum pe contemporani. Sntatea lui

att de robust pn atunci, organismul su att de oelit,

vigoarea activitii sale nu lsaser loc bnuielii despre un

sfrit apropiat. n consecin, nu se luase nici o msur pentru

eventualitatea construirii unui mausoleu special. Cnd totui

sfritul s-a produs, Senatul a gsit c locul potrivit prin

excelen pentru pstrarea urnei cu cenua Principelui celui

mai bun (Optimus Princeps) era n splendidul for pe care el

l druise Romei, n camera ncptoare de la baza Columnei.

n vecintatea imediat a acelui loc a fost cldit, doi ani mai

trziu, un templu nchinat amintirii divinizate a mpratului

defunct.

Dintre toate monumentele Forului lui Traian, Columna

este singurul care s-a conservat intact. N-au disprut, n

ntunericul veacurilor medievale, dect urna de aur i statuia

de bronz aurit a mpratului. Restul a ajuns n ntregime pn

n zilele noastre. Aceast rar cruare se datoreaz faptului c

monumentul a fost inclus n construcia unei vechi biserici

cretine. Dup drmarea lcaului ocrotitor, la nceputul

Renaterii, decis de papi tocmai pentru a scoate Columna la

vedere, aceasta n-a ncetat nici o clip de a fi n atenia general

a lumii intelectuale i sub protecia autoritilor locale. Atunci

a fost pus deasupra sa, pe locul chipului de altdat al lui

Traian, statuia de bronz a Sfntului Petru, aa cum se vede

azi, ca semn c monumentul fusese adoptat de Biseric. Ceea

ce atrgea admiraia i interesul tuturor era relieful su, cu

abundena i dinamismul scenelor reprezentate, cu nsuirile

artistice ale concepiei i ale execuiei, care preau pe atunci

exemplare. Nu exist artist al Renaterii, corifeu sau anonim,

care s nu se fi format prin studiul pasionat al imaginilor de

pe Columna Traian. n faa lor un Michelangelo sau un Rafael

rmneau n extaz, neavnd alt ambiie dect s le egaleze

virtuozitatea, fr a-i da seama c, n genialele lor producii

proprii, aveau s ntreac aceste modele, suind pn la culmi

nebnuite ale artei. n aceeai vreme, n secolul al XVI-lea, a

aprut i prima ncercare erudit de a descifra miezul istoric

al episoadelor de pe Column, prin opera clugrului spaniol

Alfonso Chcon (Ciaconus), urmat, un veac mai trziu de

o savant monografie a monumentului datorat ministrului

papal Raffaello Fabretti i de un album complet de gravuri

dup relieful ei fcut de P. Santo Bartoli.

Dup cum se vede, din cele trei semnificaii antice ale

Columnei Traiane, singura care s-a impus posteritii, mergnd

pn la eclipsarea total a celorlalte dou, a fost tocmai aceea

de comemorare a rzboaielor dacice, care, n intenia

contemporanilor lui Traian, nu avusese dect rolul secundar

de paleativ la un inconvenient de ordin arhitectonic. Interesul

pentru relieful Columnei a continuat s creasc de la Renatere

ncoace, dar nu att pentru calitile sale artistice, care sunt

departe de a mai fi privite azi cu admiraia nemrginit de

altdat, ct pentru valoarea lor documentar, fiind vorba de

un izvor de prim importan pentru studiul unei pagini mree

din istoria Imperiului Roman. Pentru noi, aceast istorie

figurat a unor evenimente capitale de la originile poporului

romn constituie unul dintre cele mai preioase tezaure de

amintiri strvechi, care, pe bun dreptate, a adus Columnei

Traiane calificativul de act de natere al neamului nostru.

Studiile referitoare la Column, ncepute n veacurile

Renaterii, au fost reluate cu mult struin n epoca modern.

Fundamentale monografii au fost scrise asupra acestui monu-

ment, ca i asupra reliefului su istoric, de W. Froehner, J.H.

Pollen, S. Reinach, E. Petersen, C. Cichorius, K. Lehmann-

Hartleben, fr a mai vorbi de nenumrate studii consacrate

problemelor sale pariale.

n Romnia, dup cum era firesc, Columna Traian a

ocupat un loc de frunte n toate lucrrile despre Dacia roman

i despre originile poporului romn. Chiar la bibliografia

special a acestui monument i a rzboaielor dacice pe care le

figureaz sculptura sa, cercettorii romni au avut contribuii

adesea remarcabile. Menionm astfel cartea Victoriei

Vaschide despre istoria cuceririi Daciei, apoi monografia lui

Teohari Antonescu despre nsi Columna Traian i studiul

lui Mihail Macrea despre o important copie pictural din

Modena. Constantin Daicoviciu i Hadrian Daicoviciu au

publicat, n 1968, o brour despre Column, iar ultimul dintre

autorii citai a tratat, mai de curnd, o serie de probleme pariale

ale reliefului. O monografie despre Column a aprut, n 1969,

n limba german. n ce ne privete personal, am cutat s

lmurim problemele reliefului, sub prisma unor noi interpretri

cu special referire la desfurarea primului rzboi dacic

n cteva lucrri de strict specialitate.

Rmas singurul element de atracie al Columnei, greu

de semnificaii i de probleme, relieful historiat al acestui

monument necesit o considerare mai insistent. Apollodor

www.cimec.ro

15

Columna Traian i semnificaia sa pentru istoria poporului romn Columna lui Traian

l-a conceput ca o istorie continu, figurat pe o band lat n

medie de un metru, care se nfura n spiral, prin 23 de

spire, de jur-mprejur pe fusul Columnei, ntocmai ca pelicula

unui film de azi pe care l-am rsuci ascendent n jurul unui

baston. Din cauza oblicitii sale continue, banda prezint

extremiti triunghiulare ascuite. Relieful nsumeaz o

lungime de circa 200 m. Coninnd peste 2500 de figuri

umane, este cea mai mare sculptur n relief din toat

antichitatea. mpratul Traian apare printre aceste figuri de

60 de ori, iar chipul demnului su adversar, Decebal, de vreo

8 ori. Studiind minuios desfurarea aciunilor reprezentate,

nvatul german Conrad Cichorius, autorul celei mai

dezvoltate monografii a acestui relief (18961900), care este

i excelent ilustrat, a distins n total 154 de scene sau episoade,

cte 77 pentru fiecare din cele dou rzboaie, plus o scen

alegoric ntre ele, reprezentnd-o pe zeia Victoria. Diviziunile

stabilite de Cichorius au rmas clasice, fiind curent folosite

n toate studiile tiinifice.

Din punct de vedere artistic, relieful Columnei Traiane

reprezint apariia unui gen original n arta antic. Executat

de sculptori greci din Siria condui de Apollodor din Damasc,

dar dup indicaii primite din partea oficialitilor din Roma,

grandioasa band sculptat n spiral exprim o mbinare a

gustului oriental pentru decor bogat, pentru reprezentri

ncrcate, cu concepia realist specific roman. Calitile

reprezentrilor sunt eminente: vivacitatea i dramatismul

aciunilor, agitaia maselor, nobleea figurilor, acurateea

execuiei, armonizarea gesturilor i atitudinilor. Dar aceste

trsturi principale nu pot ascunde unele defecte care denot

un nceput de decaden a artei antice. E vorba de stngcii n

reprezentarea peisajelor, a aspectelor urbane, a cetilor, de

erori de perspectiv i de proporii, de frecventa nlocuire a

unor detalii sculpturale prin elemente specifice picturii.

O calitate artistic demn de relevat este abilitatea de a

sintetiza episoadele povestite. Sintetizarea era impus de

dimensiunile limitate ale spaiului destinat reliefului. Artitii

s-au achitat cu mult ingeniozitate de aceast ndatorire,

ajutndu-se de trucuri diverse: iluzia maselor numeroase

reprezentate de fapt numai prin civa indivizi, selectarea

elementelor celor mai caracteristice ale unui episod,

concentrarea de subiecte n cte o singur scen, exprimarea

de stri psihologice prin gesturi convenionale dar elocvente,

utilizarea de simboluri pentru noiuni abstracte i aa mai

departe. Dar dac artitii s-au lsat att de covritor dominai

de nevoia economiei de spaiu e fiindc se aflau sub servitutea

altei obligaii: aceea de a reda o succesiune complet a

episoadelor i de a le nfia cu coninutul lor real. Este evi-

dent c aveau de reprodus, cu toat rigoarea, un text dat, care

nu putea fi dect acela al Comentariilor scrise de nsui

mpratul Traian despre rzboaiele sale. Acest text, intitulat

Dacica, s-a pierdut n ntregime, totui se tie sigur c a existat

i c a servit de baz tuturor scrierilor din vechime despre

Rzboaiele dacice. Din nefericire, nici aceste scrieri nu s-au

pstrat, dei au fost foarte numeroase. Chiar tirile de la

Cassius Dio, singurele ceva mai consistente de care dispunem

cu privire la acest subiect, nu reprezint direct textul istoricului

respectiv, ci un biet rezumat, srac i ncurcat, fcut de

clugrul bizantin Xiphilinus, n secolul al XI-lea.

n aceast disperat situaie a izvoarelor scrise, relieful

Columnei, echivalent cu o oper literar complet, reflectnd

nsi relatarea competent a aceluia care a condus i a svrit

faptele povestite n scenele sculptate, capt o valoare

documentar de nepreuit. Obieciunea pe care au formulat-o

unii cercettori (de ex. Eugenia Strong i K. Lehmann-

Hartleben) i care nc i mai face drum, c semnificaia real

a reliefului ar fi diminuat printr-o subordonare fa de niscaiva

exigene estetice care ar fi denaturat ordinea i sensul

evenimentelor, nu constituie dect o absolut eroare. Nici un

exemplu, de pe toat Columna, nu poate fi invocat serios n

sprijinul unei asemenea subordonri. n succesiunea scenelor

de pe relief nu se constat dect respectul pentru adevr, fr

nici o alt preocupare, mergndu-se pn la repetarea scenelor

cu subiecte similare, fiindc aa se repetau n realitate, iar,

uneori, riscndu-se chiar monotonia, att de antinomic

veleitilor estetice. O rnduire a episoadelor dup libera

fantezie estetic a artistului ar fi fost cu desvrire absurd,

contrazicnd nsi esena realist a genului. Dac exist o

subordonare, aceasta este exact invers. Dup cum am vzut,

artitii Columnei erau tot timpul ncorsetai de necesitatea de

a exprima numai adevrul, fr nici o posibilitate de iniiativ

proprie. De altfel, care edil al Romei le-ar fi permis o

intervenie inovatoare n schiele stabilite pe baza

Comentariilor imperiale? Iar ca nsi oficialitatea s fi

conceput o derogare de la textul acestor Comentarii ar fi fost

cu totul fr rost. nfiarea normal a desfurrii unui rzboi

victorios nu aducea nici un prejudiciu orgoliului roman, ci

dimpotriv. De fapt, scrupulul realitii apare att de riguros

pe relieful Columnei, nct sunt nfiate fr nici o reticen

chiar episoade de natur s ating susceptibilitile acestui

orgoliu, cum e cazul cu scenele n care se vd rnii romani

ori prizonieri romani torturai, nici mcar de brbai, ci de

femei dace. Pe de alt parte, relieful i prezint pe daci cinstit,

n atitudini demne i chiar sublime, fr vreo ncercare de a

le pune virtuile rzboinice i figurile n inferioritate fa de

ale romanilor. Este un spirit nou, de realism obiectiv, pe

care nu-l cunoscuser nici arta egiptean, nici artele vechiului

Orient, nici arta elen clasic, i care face onoare superioritii

morale a civilizaiei romane.

Dar dac recunoatem fr rezerve valoarea

documentar a reliefului de pe Column n ce privete

succesiunea real a episoadelor i autenticitatea aciunilor pe

care le sintetizeaz fiecare, nu putem avea aceeai atitudine

fa de reprezentrile amnuntelor de peisaj, de topografie,

de construcii, care inevitabil erau convenionale. Chiar tipurile

etnice, costumele i armele, dac nu li se poate pune la ndoial

realitatea, trebuie s se admit c reprezentau generalizri ale

ctorva modele selectate. Artitii lui Apollodor nu cunoteau

din proprie experien tot ceea ce trebuiau s sculpteze. Figurau

ceea ce textul literar le impunea, recurgnd la chipurile

captivilor pe care i vedeau la Roma i la armele lor capturate,

iar n rest se cluzeau dup ceea ce li se spunea de ctre alii

sau numai dup imaginaie. Agenii oficiali care le controlau

schiele nu erau mai buni cunosctori ai amnuntelor i, de

altfel, nici nu exista n antichitate prea mult exigen n

www.cimec.ro

16

Columna lui Traian Columna Traian i semnificaia sa pentru istoria poporului romn

aceast privin. n consecin, cei care mping preuirea forei

documentare a Columnei pn la preciziuni de aspecte

topografice (mai toi cercettorii din trecut, dar mai cu seam

T. Antonescu i G. A. Davies) se nal tot att de mult ca i

cei care i pun n dubiu orice valoare.

S ne mulumim cu ceea ce acest monument ne poate

oferi ca date sigure de o primordial importan: sensul

evenimentelor, realitatea lor, succesiunea lor complet i

precis, adic ceea ce ne-ar fi oferit n esen i Comentariile

lui Traian dac s-ar fi pstrat. Relieful Columnei poate fi privit

ca albumul de ilustraii al acestui text scris (C. Daicoviciu),

dar i mai exact e de considerat ca nsi traducerea sistematic

i scrupuloas a acestui text n imagini. Este o imens comoar

de tiri, dar o comoar cu taine i cu cheie, cci pentru a o

descifra este nevoie s se refac drumul invers, al traducerii

imaginilor n idei i n cuvinte, ceea ce, n lipsa originalului

scris i n extrema srcie a altor izvoare, reprezint o operaie

infinit mai grea dect osteneala artistului care a transpus ideile

n figuri.

De aceea, lectura acestor scene, n cele patru secole

scurse de la Ciaconus pn azi, a fcut progrese foarte lente.

Abia n epoca de dezvoltare a activitii tiinifice i a spiritului

critic din ultimul veac, s-a ajuns la mai mult lumin, discuiile

tiinifice duse de pe poziii diverse de concepie i de metod

soldndu-se, din etap n etap, cu ncheieri unanim acceptate.

Sunt nc prea puine ncheierile de acest fel, dar continua lor

sporire dovedete c cercetrile i dezbaterile de opinii nu

sunt zadarnice i c dac, pentru multe din problemele

reliefului, soluiile definitive rmn pe seama viitorului, exist

ferme sperane c acest viitor va putea fi considerabil scurtat.

n aceast privin, tiinei istorice romneti i revine

o datorie de onoare, pe care acum, cnd dispune de fidele

reproduceri dup relieful Columnei, i-o va putea ndeplini

cu i mai mult eficacitate dect n trecut. S ne felicitm c

avem la noi n ar aceste reproduceri, c oricine va putea s

le vad pe ndelete, s le studieze, s mediteze asupra

adevrului pe care l ascund. Ceea ce nainte eram nevoii s

cutm numai n ilustraiile imperfecte ale crilor, adesea

greu accesibile, de acum nainte ne va aprea direct n faa

ochilor, ngduindu-ne s nlm gndurile i simirile cu

mai mult avnt i cu o mai limpede nelegere, pn la

vremurile ndeprtate ale originilor noastre naionale, crora

aceste imagini sculpturale le sunt nemijlocite mrturii.

Dac pentru contemporani imaginile erau uor de

neles, fiindc era vorba de fapte general cunoscute pe atunci

i de un text de baz, care se afla la ndemna oricui n

bibliotecile publice i particulare, pentru noi cei de azi, care

nu mai dispunem de acea scriere oficial i nici mcar de

lucrrile ulterioare inspirate de slova ei, coninutul acelor

reprezentri figurate rmne n bun parte enigmatic.

Este adevrat c vreo cteva tiri scrise, rare i rzlee,

care s-au salvat prizrite pe la unii autori mai trzii, ne pot

ajuta s nelegem sensul general al aciunilor reproduse pe

relieful Columnei i s identificm semnificaia unor scene,

dar i aceste tiri, prin extremul lor laconism, prin lipsa lor de

claritate i de continuitate i, adesea, prin modul defectuos n

care au fost transmise, ridic unele probleme dificile. Este

ceea ce explic att ncetineala progreselor nregistrate pn

acum n descifrarea reliefului, ct i frecventele dezacorduri

dintre cercettori asupra metodelor de cercetare i interpretare.

Pe de alt parte, frnturile de tiri scrise care s-au pstrat

despre cele dou rzboaie dacice ale lui Traian nu aduc lumini

pentru fiecare n aceeai proporie. Pe cnd, de bine de ru,

despre primul rzboi (101102 e.n.) aceste tiri ofer destule

indicaii pentru a nlesni o interpretare continu i concludent

a reliefului respectiv, despre cel de-al doilea (l05106 e.n.)

sunt extrem de avare, abia permindu-ne s aflm cum a

nceput acest rzboi i care i-a fost sfritul, n rest lsndu-

ne s ne descurcm fr nici o sugestie ajuttoare n faa

complicatelor episoade de pe Column care l reprezint.

De altfel, mai toate aceste crmpeie de tiri scrise provin

de la un singur autor: Cassius Dio, un nsemnat personaj din

epoca Severilor, senator i fost consul, guvernator al provinciei

Pannonia Inferioar, care, cu o documentare contiincioas, a

scris, la mai bine de un secol dup Traian, o Istorie Roman n

80 de cri. Dintre aceste cri, mai mult de jumtate s-au pierdut,

nesalvndu-se din coninutul lor dect buci sporadice citate

de ali autori sau, mai ales rezumate, ntr-o vreme trzie, de

clugrul Xiphilinus, secretarul mpratului bizantin Mihail VII

Ducas Parapinakes (10671078). Din nefericire, cartea 68 din

Cassius Dio, care trata despre domnia lui Traian, cade tocmai

n acest lot prescurtat, care mai prezint i cusurul de a nu

constitui ceea ce se nelege printr-un rezumat propriu-zis, adic

o condensare raional a unui text fr sacrificarea precizrilor

eseniale, ci const doar dintr-o nirare de pasaje desprinse din

textul original, printr-o selecie arbitrar, i apoi puse cap la

cap. Desigur, pasajele rzlee sunt, fiecare n parte, de o fidel

autenticitate, dar procedeul juxtapunerii lor mecanice, departe

de a fi inofensiv, atrage dup sine primejdia de a-l induce n

eroare pe cititor, dndu-i impresia de relatare a unei aciuni

unitare i continue, cnd, n realitate, este vorba de fapte diferite

i fr legtur ntre ele. Capitolul referitor la rzboaiele dacice

ale lui Traian transmis de Xiphilinus, extrem de scurt, este

tocmai unul dintre cele mai grav viciate prin acest procedeu,

mprejurare de care nu s-a prea inut seama n interpretrile

ncercate pn acum, precum vom avea prileju1 s artm mai

departe, la locul cuvenit. Se nelege c o confruntare a istoriei

figurate de pe Column cu ceea ce ne-a pstrat Xiphilinus din

Cassius Dio despre aceleai evenimente nu prezint coincidene

de fapte dect la foarte mari distane, numeroase scene de pe

cuprinsul intermediar al reliefului rmnnd fr corespondent

n izvorul scris. Sensul lor poate fi lmurit numai prin deducie,

n funcie de rarele scene sigur identificate ntre care sunt

cuprinse, innd seama c episoadele reproduse pe Column

corespund unei nlnuiri logice de fapte reale.

n cele ce urmeaz, pim la o lectur a reliefului

Columnei pe baza criteriilor amintite, avnd ferma convingere

c niciodat nu se va putea ajunge la o just nelegere a acestui

preios monument historiat dac nu se vor avea n vedere

urmtoarele premise: caracterul documentar de proces-ver-

bal autentic i oficial al scenelor reprezentate, ca traducere

riguroas n imagini a textului Comentariilor imperiale,

succesiunea exact i complet a episoadelor, aa cum erau

menionate n acest text, fr nici o subordonare fa de

www.cimec.ro

17

Columna Traian i semnificaia sa pentru istoria poporului romn Columna lui Traian

cerinele unei compoziii artistice; veracitatea scrupuloas a

subiectelor reprezentate; precderea acordat aciunilor la care

a participat mpratul i, prin urmare, raritatea sau absena

altor fapte; caracterul sintetic al scenelor n care artistul a

cutat s sugereze elementele eseniale ale aciunilor, prin

trucuri convenionale, iar nu s prezinte instantanee

fotografice; imperfeciunea amnuntelor cu privire la costume,

peisaje, ceti, arme, tipuri etc., ca urmare a acestei preocupri

sintetizante i a insuficienei cunotinelor de care dispunea

artistul; absena oricrui gest lipsit de semnificaie;

superioritatea categoric a reliefului Columnei ca document

istoric fa de orice mrturie scris, att n ce privete ordinea

cronologic a episoadelor, ct i subiectul lor; prioritatea de

principiu a reliefului n eventuale contradicii cu mrturiile

scrise, care, din capul locului, se cer privite cu precauie critic,

din cauza modului indirect, sporadic, fragmentar i defectuos

n care au fost transmise; atenie la procedeul lui Xiphilinus

de a alctui rezumatul operei lui Cassius Dio printr-o

amgitoare alturare de excerpte disparate.

Pe de alt parte, dei ar trebui s se neleag de la sine,

este bine s insistm, din cauza frecventelor abateri de pn acum,

asupra principiului tiinific elementar ca acel ce atac problema

rzboaielor dacice relatate n scenele Columnei Traiane s se

elibereze cu desvrire de obsesia oricror prejudeci motenite

de la interpretrile greite din trecut, precum i de orice tentaie a

fanteziei de a se substitui concordanei dintre mrturiile izvoarelor.

Nu trebuie s se uite c interpretarea cea mai apropiat de adevr

este aceea n care nu rmne loc pentru nici un semn de ntrebare

i n care toate indicaiile documentare i gsesc corespondena

lor fireasc, fr ca vreuna s rmn suspendat n aer. Desigur,

insuficiena datelor concrete l oblig mereu pe cercettor s

recurg la ipoteze, dar datoria sa este s se mrgineasc la ipoteze

bazate pe deducii n acord cu restul faptelor, ferindu-se de

simplele presupuneri gratuite, lipsite de orice contact cu indicaiile

documentare. De asemenea, cercettorul Columnei trebuie s

aib mereu n vedere mprejurrile istorice generale i situaia

politic i strategic a beligeranilor de la o faz a rzboaielor

la alta.

www.cimec.ro

18

PRI MUL RZBOI DACI C AL LUI TRAI AN

Cele 77 de scene din jumtatea reliefului referitoare la

primul rzboi se grupeaz n trei campanii diferite, care au

fost duse pe diverse teatre de lupt. Aceste campanii, distinse

mai nti de W. Froehner, dar interpretate just numai ulterior

(C. Cichorius, E. Petersen, T. Antonescu, R. Paribeni etc.)

sunt urmtoarele: I. Campania din Dacia, n vara i toamna

anului 101 (scenele IXXX); II. Campania din Moesia

Inferioar, n iarna i primvara anului l02 (scenele XXXI

XLVI); III. Campania ulterioar din Dacia, n vara i toamna

anului 102 (scenele XLVIILXXVII). Pentru al doilea rzboi,

aciunile reprezentate fiind mai complexe i mai puin ajutate

de indicaiile izvoarelor literare, nc nu s-a ajuns la o diviziune

tot att de clar pe campanii. Fapt este c toate aciunile acestui

rzboi s-au petrecut n cuprinsul Daciei Carpatice, la nord de

Dunre.

Conflictul n-a fost un eveniment izolat, ivit abia n

vremea lui Traian i a lui Decebal, ci nfruntarea acestor mari

personaliti a reprezentat doar etapa suprem a unui proces

nceput cu secole mai nainte, de la primele contacte dintre

puterea Romei i neamul geto-dac. Att mpratul roman, ct

i regele dac n-au fost dect exponenii popoarelor pe care le

crmuiau i ale cror eluri vitale le slujeau, ntocmai ca toi

predecesorii lor, pe linia unei necesiti istorice de nenlturat,

mai presus de orice cuget i de orice voin omeneasc. nc

de la sfritul secolului al III-lea .e.n., unificnd Italia i

trebuind s-o apere de pirateriile ilirice i de atacurile

cartagineze i elenistice, romanii s-au vzut silii s treac

Adriatica i, dup ce s-au asigurat de stpnirea Mediteranei,

s-i statorniceasc puterea n Peninsula Balcanic prin

transformarea Macedoniei i a Greciei n provincii. Chiar de

pe atunci s-ar fi putut prevedea c expansiunea lor n-avea s-

i gseasc o limit n aceast direcie dect la Dunre, singurul

obstacol important, lung i continuu, pe care natura l oferea

ntinsului lor domeniu. Totui, aceast int nu le-a devenit

clar dect mai trziu, dup ce le-a fost impus de aprigele

atacuri asupra provinciei lor din Macedonia din partea

diverselor triburi ilirice, celtice i trace vecine, sprijinite de

populaiile transdanubiene i, n primul rnd, de geto-daci,

care, de la nceput, au luat o atitudine potrivnic fa de

instalarea unei puteri occidentale n preajma spaiului lor. Abia

n al doilea sfert al secolului I .e.n., trupele romane au atins

pentru prima oar Dunrea, prin dou aciuni divergente, una

n dreptul Banatului, la 74 .e.n., cnd proconsulul Caius

Scribonius Curio, dup o campanie victorioas mpotriva

dardanilor, i-a mpins naintarea pn la Porile de Fier, fr

a cuteza ns s nfrunte desimea codrilor daci de pe malul

cellalt, i alta la gurile fluviului, doi ani mai trziu, cnd

Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus, dup ce a nfrnt rezistena

tracilor din Balcani i a geilor din Dobrogea, a supus toate

oraele greceti de pe litoralul de vest al Pontului Euxin.

Aciunea lui Curio spre Porile de Fier n-a fost dect o simpl

demonstraie, dar aceea a lui Varro Lucullus urmrea o afirmare

statornic. Numai c, n anul 61 .e.n., unul dintre urmaii

si, C. Antonius Hybrida, avea s fie nvins de o rscoal a

cetilor pontice, susinut de gei, iar forele romane au trebuit

s prseasc aceste regiuni, care, curnd, vor intra n aria

impuntoarei puteri a lui Burebista.

Aceast ilustr personalitate getic izbutise tocmai

atunci, cu ajutorul dacului Deceneu, s conving toate uniunile

regionale ale triburilor daco-getice de primejdia iminent a

expansiunii romane i de trebuina de-a adera la conducerea

lui, izbutind astfel s ntemeieze, ntr-un larg spaiu carpato-

danubian din sud-estul Europei, o formidabil unitate politic

i militar. Aceast putere devenise deosebit de amenintoare

pentru Roma, care tocmai atunci se afla n toiul rzboiului

civil dintre Iulius Caesar i Pompeius. Regele get n-a scpat

ocazia de a contribui la slbirea puterii dumane, intervenind

n acest conflict de partea lui Pompeius, care, reprezentnd

provinciile romane din Orient, putea s-i garanteze mai sigur

interesele. Btlia de la Pharsalos ns a hotrt soarta

rzboiului prin nfrngerea lui Pompeius nainte ca

importantul contingent promis de Burebista s fi putut ajunge

pe teatrul de lupt. nvingtorul, Caesar, n-a uitat gravitatea

ameninrii getice de care reuise s scape i tocmai era gata

de a ntreprinde o mare expediie destinat s suprime puterea

lui Burebista, n momentul cnd, la idele lui martie din anul

44 .e.n., a fost asasinat de dumanii si din Senatul roman.

Expediia n-a mai avut loc, dar curnd a disprut i regele

get, rpus, de asemenea, de o conspiraie, urzit de efii de

triburi din subordinea sa, care, neputnd accepta tendinele

www.cimec.ro

19

Columna lui Traian Primul rzboi dacic al lui Traian

sale de centralizare statal, antinomic tradiiilor nc vii de

autonomie tribal, s-au desprit n patru formaii diferite.

Unele dintre aceste formaii au continuat, n ariile lor mai

restrnse, evoluia statal indicat de Burebista, ceea ce,

ndeosebi dacilor din Carpai, condui odinioar de Deceneu,

avea s le asigure o for mereu n progres, pn la aspectele

remarcabile din vremea lui Decebal.

n mprejurrile celuilalt rzboi civil, dintre Octavianus

i Marcus Antonius, aceeai atitudine a lui Burebista a fost

manifestat de urmaul su din inuturile getice, Dicomes,

care a luat partea lui Antonius, beligerantul sprijinit pe Ori-

ent; dar i de data aceasta victoria s-a decis n favoarea

adversarului occidental, prin victoria naval a acestuia de la

Actium, din 31 .e.n., fr ca greutatea ajutorului getic s se

fi putut face nici acum simit. nvingtorul, Octavianus, care

avea s devin curnd mprat sub numele de Augustus, a

luat hotrrea de a fixa definitiv frontiera imperiului su pe

Dunre. Generalul su M. Licinius Crassus, dup ce a nimicit

o invazie bastarn n Tracia, n 2928 .e.n., a cucerit ntreaga

Dobroge (Scythia Minor) pn n Delt, nvingnd rezistena

geilor locali de sub conducerea regilor Dapyx i Zyraxes.

Acest teritoriu dintre Dunre i Mare a fost alipit la Imperiu,

dar, deocamdat, ntr-o form indirect, fiind pus sub mandatul

regilor odrisi ai Traciei, devenii clieni ai Romei.

Regiunile ilirice dintre Adriatica i Sava, a cror

cucerire Octavianus o ncepuse nc nainte de Actium, au

fost supuse complet, adugndu-li-se i Pannonia pn la

Dunre, precum i Noricul i Vindelicia. n sfrit, dup

cucerirea acestor ri i mai ales dup potolirea ultimei mari

rscoale iliro-panonice din 69 e.n., ntregul curs al Dunrii,

pe toat lungimea sa enorm, de la izvoarele din Vindelicia

pn la Marea Neagr, devenise frontiera Imperiului Roman,

care, prelungit n vest pn la Marea Nordului prin linia

Rinului, constituia un reazem temeinic al lumii mediteraneene

n faa vastelor ntinderi din nordul i rsritul Europei.

Totui, frontiera de pe cele dou fluvii era departe de

eficacitatea ideal pe care prea s-o ofere. Pe lng faptul c

iarna apele acestor fluvii nghea, pierzndu-i temporar

valoarea de obstacol, mai prezentau i cusurul c linia lor era

lipsit de un traseu continuu rectiliniar. Cel mai grav dintre

inconvenientele acestui traseu l reprezenta enorma sinuozitate

pe care cursul Dunrii o descrie n jurul Daciei, ntre cotul

su panonic de la Aquincum (Budapesta), i cealalt flexiune

brusc, din nordul Dobrogei, de la Dinogeia (Garvn), peste

drum de Galai, lsnd n mijloc formidabila coroan de muni

a Transilvaniei, care, stpnit de o putere solid organizat ca

aceea a dacilor de dup Burebista, domina i amenina pn

la zdrnicire ntregul dispozitiv al aprrii romane dintre

Adriatica i Pontul Euxin.

nlturarea acestui neajuns capital se impunea

Imperiului Roman ca o necesitate de prim ordin. Singura

soluie consta n suprimarea puterii dace i anexarea masivului

carpatic. Dar era o soluie extrem de anevoioas, pentru

realizarea creia va mai fi nevoie de uriae strduine, cu att

mai grele, cu ct dacii, dndu-i seama, la rndu-le, de

importana strategic pe care o avea patria lor i de nverunata

primejdie roman pe care puterea lor o stimula, i vor lua

mereu msuri de ntrire i de rezisten. Chiar de la nceputul

instalrii frontierei romane pe Dunre, luptele dintre geto-

daci i romani, de cele mai multe ori iniiate prin incursiuni

getice i dace n dreapta fluviului, au ajuns endemice.

mpratul Augustus a ripostat, printre altele, prin expediia

generalului su Sextus Aelius Catus, de prin anii 911 e.n.,

care i-a nvins pe geii din esul Munteniei, a deportat 50 000

dintre ei n dreapta fluviului, i-a silit pe ceilali s-i prseasc

cetile i, nimicind astfel uniunea triburilor getice care fusese

odinioar temelia puterii lui Burebista, a creat, n faa graniei

de la Dunrea de Jos, o larg zon de acoperire aproape

depopulat. Ulterior, dup desfiinarea regatului odris, n 45

e.n., i dup extinderea provinciei Moesia, cu garnizoanele

sale, de-a lungul ntregii poriuni respective a fluviului pn

la Mare, forele romane au strns i mai mult cercul n jurul

Daciei, instalnd, sub mpraii din dinastia Flaviilor, castre

permanente n zona de dealuri a Munteniei i Olteniei, n

dreptul pasurilor carpatice. Grelele lupte purtate n vremea

rzboiului civil de dup moartea lui Nero pn la Vespasian,

pe de o parte n Dobrogea, mpotriva sarmailor roxolani i

pe de alta, concomitent, n restul Moesiei, mpotriva

incursiunilor dace, au artat ct de precar rmnea situaia

strategic la Dunrea de Jos, atta vreme ct dacii nu erau

inui n fru. Pn la urm, Vespasian a restabilit ordinea, nu

numai prin victoriile obinute, ci i prin plata unor subsidii

acordate dacilor, aparent ca daruri ctre nite supui, dar, de

fapt, ca pre al pcii. Firete, eficacitatea unui asemenea mijloc

nu putea fi durabil, depinznd mereu de starea echilibrului

de fore.

Este exact ceea ce avea s se dovedeasc sub Domiian,

care, n timp ce era ocupat cu grele rzboaie pe frontiera

Rinului i a Dunrii panonice, s-a vzut ntmpinat de daci

cu cererea de urcare a subsidiilor. Cum mpratul nu era dispus

s la fac pe plac, ei au atacat pe neateptate Moesia, n anul

85 e.n., distrugnd o armat roman i omorndu-l n lupt

pe nsui guvernatorul provinciei, Oppius Sabinus. Problema

dac intra astfel ntr-o faz extrem de acut. Domiian a

reacionat prompt, dispunnd msurile de rigoare, n urma

crora agresorii au fost respini peste Dunre. Provincia

Moesia, mult prea lung pentru sarcinile ei militare din ce in

ce mai complexe, fu mprit, n anul 86, n Moesia Supe-

rior, la apus de rul Ciabrus (Tibria), i Moesia Inferior, la

rsrit, pn la Gurile Dunrii. Apoi, o armat imperial, pus

sub ordinele lui Cornelius Fuscus, prefectul pretoriului, a luat

contraofensiva, trecnd fluviul, desigur prin Banat, pentru ca,

pe drumul cel mai scurt, s ajung ct mai repede n centrul

rii inamice. n faa primejdiei, regele dacilor Duras (sau

Diurpaneus), simindu-se prea btrn pentru a-i face fa,

abdic n favoarea nepotului su de frate, Decebalus, dotat cu

extraordinare nsuiri militare i politice. Cassius Dio (LXVII,

6) l caracterizeaz astfel: era foarte priceput n planuri de

rzboi i iscusit n ndeplinirea lor, tiind s aleag momentul

cel mai potrivit pentru a-l ataca pe duman sau pentru a se

retrage; dibaci n a ntinde curse, era un destoinic lupttor i

se pricepea s trag depline foloase dintr-o biruin, dar i s

ias cu bine dintr-o nfrngere; din aceast pricin, mult vreme

a fost un adversar de temut pentru romani. Decebal avea s

www.cimec.ro

20

Columna lui Traian Primul rzboi dacic a lui Traian

se dovedeasc la nlimea mprejurrilor, ncepndu-i

domnia cu un act de abilitate tactic ncununat de o rsuntoare

biruin. n cursa pe care ia ntins-o comandantului roman, la

o strmtoare, acesta i-a gsit moartea, mpreun cu toat

oastea sa, ntr-o nfrngere dezastruoas. Decebal nu s-a grbit

s-i exploateze succesul printr-o nou invazie n Moesia, unde

ar fi riscat s-i compromit prestigiul cptat, ci, nelept, a

cutat s profite de acest prestigiu pentru a-i ntri autoritatea

n interior i a-i atrage aliai din afar.

n replica sa, Domiian a procedat i de data aceasta cu

o energic operativitate, concentrnd o armat i mai

important, pe care acum a ncredinat-o consularului Tettius

Iulianus, un general destoinic i cu experien, care, trecnd

Dunrea i lund i el drumul Banatului, a reuit s evite

insidiile dacilor i s-i bat la Tapae. n aceast mprejurare

potrivnic i-a dovedit Decebal calitile tactice mai mult chiar

dect n cazul unei biruine, izbutind s limiteze efectele nfrn-

gerii i s ntrzie urmrirea inamic. Pn la urm, ns,

trupele romane s-au apropiat de munii Sarmizegetusei Regia,

ceea ce l-a determinat pe Decebal s cear pace. Domiian era

pe cale s-o refuze, spernd ntr-o izbnd radical a generalului

su, dar fiindc, ntre timp, n Pannonia, unde se afla, suferise

o grea nfrngere din partea marcomanilor i a quazilor, s-a

vzut nevoit s primeasc cererea dac, ncheind, n 89, o

pace de compromis, prin care Decebal intra n relaii clientelare

cu Imperiul, recunoscndu-se supus mpratului. Actul

nchinrii a fost ndeplinit nu de el personal, ci de fratele su,

Diegis, totui n mod valabil, cci acesta era motenitorul

designat al tronului dac. n schimb, lui Decebal i se rennoia

stipendiul, dar fr spor, i i se asigurau ajutoare n meteri

pentru construcii de ceti i de maini de rzboi, spre a se

prezenta bine narmat n faa eventualilor dumani ai Romei,

care acum erau considerai i ai lui.

ncheiat n asemenea condiii echivoce, pacea din anul

89 a nemulumit profund clasa senatorial din Roma, cu care

Domiian, caracter orgolios, despotic i lipsit de tact personal,

se afla ntr-un aprig conflict. Posteritatea n-a nregistrat dect

aprecierile defavorabile ale acestei clase, din care se recrutau

i istoricii timpului. Totui, pacea nu era chiar att de rea

pentru romani. Decebal pierduse mult din independena sa i

se afla strict legat de interesele Imperiului. Este incontestabil

c el a respectat pactul cu credin n tot timpul domniei lui

Domiian i a lui Nerva, pn la rzboiul din 101, izbucnit

exclusiv din iniiativa lui Traian. Desigur, fidelitatea regelui

dac nu se explic numai prin satisfacia pe care i-o ddeau

subveniile i ajutoarele primite regulat (chiar de la Traian

pn la 101), ci, mai ales, prin garaniile militare pe care

romanii i le luaser de la nceput. Autoritatea statului dac

fusese pretutindeni ndeprtat de la Dunre i ngrdit n

cercul de muni al Transilvaniei. Ca i Muntenia i Moldova,

Oltenia i Banatul deveniser zone de acoperire ale frontierei

romane de pe fluviu. Dar dac, deocamdat, Decebal prea

docil, nu e mai puin adevrat c prosperitatea rapid a statului

dac i consolidarea forelor sale inspirau romanilor temeri

serioase pentru viitor. Considerabilul sistem de fortificaii de

tehnic superioar din munii Sarmizegetusei, creat cu

ajutoare romane, putea servi nu numai mpotriva inamicilor

Romei, dar i mpotriva Romei nsi, n cazul unei ruperi,

oricnd posibile, a echilibrului de la baza pactului. De aceea,

Traian, n acord cu sentimentul unanim al opiniei publice

romane, de ndat ce a venit la tron, i-a fcut un principal

punct de program din suprimarea acestui focar de

ngrijortoare perspective.

Traian, soldat de carier, care i dduse dovezile de

capacitate militar pe frontiera Rinului nc nainte de a deveni

mprat, mprtea cu profund convingere aspiraiile

rzboinice ale romanilor. De ndat ce a primit purpura

imperial, dup moartea lui Nerva, n anul 98, el a nceput

vaste i minuioase pregtiri n vederea unei expediii decisive,

care trebuia s duc la nimicirea puterii lui Decebal i la trans-

formarea Daciei n provincie roman. Bineneles, nici

perspectiva capturrii uriaelor tezaure acumulate de regii daci,

n multe secole de neatins independen, nu era strin de

scopurile expediiei proiectate.

Cnd pregtirile au fost puse la punct, Traian a pornit

rzboiul, care a fost declarat solemn la Roma, prin rituri

tradiionale, la 25 martie, anul 101. Apoi a plecat spre Dunre,

unde, probabil prin luna mai, a nceput ostilitile n fruntea

unor fore impuntoare, care, dup calcule destul de moder-

ate, trebuie s fi totalizat cam 100 000 de oameni. O asemenea

mas de soldai, enorm pentru acele timpuri, era necesar

pentru obinerea unui rezultat categoric ntr-un timp scurt.

Copleit de fore mult superioare att cantitativ, ct i calitativ,

Decebal putea fi considerat de la nceput pierdut. Era de

ateptat din partea sa o rezisten nverunat, dar fr sperana

nlturrii unei nfrngeri desvrite. Traian, care pornise

rzboiul la momentul voit de el i n direcia aleas de el, se

putea crede stpn deplin al iniiativei operaiilor. Dar

desfurarea ulterioar a evenimentelor avea s-i arate ct de

mult se nela i ct de imprudent subestima resursele

adversarului su. E ceea ce vom vedea mai departe.

Deocamdat, trebuie s lmurim o chestiune principal.

Pe unde a trecut Traian Dunrea i pe ce drum a ptruns n

Dacia? ntrebarea ar rmne n negur dac rspunsul nu ni

l-ar da singurele cinci cuvinte care s-au salvat din Comentariile

lui Traian: inde Berzobim deinde Aizim processimus (de acolo

am naintat la Berzobis i pe urm la Aizis), citate de

gramaticul Priscianus din secolul al V-lea, ca exemplu de stil

sec, cazon, lipsit de caliti literare. Desigur, aceast dezolant

ariditate stilistic explic de ce scrierea imperial, nefiind

destul de atractiv pentru a fi recopiat de generaiile mai

trzii, s-a pierdut cu totul, lipsindu-ne astfel de cel mai preios

document scris asupra rzboaielor dacice. Cel puin, ns, cele

cinci cuvinte, citate din partea de nceput a lucrrii imperiale

(n primo Dacicorum), ne ofer cheia problemei pe care ne-

am pus-o, cci localitile pe care le precizeaz sunt cunoscute

din itinerarele de mai trziu: Berzobis se afla n Banat, pe

locul satului actual Berzovia (fost Jidovin), iar Aizis ceva

mai la nord, la Frliug, lng Pogni. Era vorba, deci, de

drumul dintre Lederata i Tibiscum, menionat n Tabula

Peutingeriana cu urmtoarele staii: Lederata (Rama n

dreapta Dunrii, n Serbia), Apus Flumen (rul Cara, probabil

la confluena cu prul Vicinic, n Banatul iugoslav), Arcidava

(Vrdia, la nord-est de Oravia), Centum Putei (O sut de

www.cimec.ro

21

Columna lui Traian Primul rzboi dacic al lui Traian

puuri, la Surducul Mare), Berzobis (sau Berzovia), Aizis

(sau Azizis), Caput Bubali (Capul Boului, lng Delineti),

Tibiscum (Jupa, lng Caransebe). Acest itinerar reprezint

calea cea mai dreapt pe care o armat venit dinspre

provinciile occidentale ale Imperiului putea ptrunde n

direcia Sarmizegetusei, continund de la Caransebe, spre

est, prin valea Bistrei i prin ara Haegului. Dup cum vom

vedea imediat, Dunrea a fost trecut n acelai timp i de o a

doua armat a lui Traian, pe la Drobeta, naintnd pe un alt

drum, care ducea tot la Tibiscum.

De acum nainte, dm cuvntul imaginilor de pe

Column. n descrierea care urmeaz, am pstrat mprirea

n scene numerotate cu cifre romane, fcut de Conrad

Cichorius. Pentru o mai uoar identificare a lor pe mulajele

expuse la Muzeul Naional de Istorie a Romniei, am notat

numrul acestora cu cifre arabe.

www.cimec.ro

22

PRI MA CAMPANI E: ANUL 101 N DACI A

Cele trei scene descrise pn aci, pe lng rolul de a

umple un spaiu mort de la extremitatea ascuit a bandei

spirale, au i semnificaia unei atmosfere de via agitat a

trupelor de pe frontier n ajunul unui rzboi. Aciunile

rzboiului nsui abia de aci nainte ncep.

ARMATELE ROMANE TREC DUNREA

(SCENELE IV-V = 4-5, foto p. 117)

Aciunea din scena IV, la care privete zeul Danuvius,

este trecerea fluviului de ctre armata roman. Din oraul

figurat n scena precedent, pe o poart a zidurilor lui crenelate,

se vd ieind n mar soldai care pesc pe un pod de vase.

Navele sunt unite solid prin brne groase. Sunt soldai din

legiuni, uor de recunoscut dup scutul mare semicilindric

(scutum) i dup platoa lor confecionat din fii de piele

(lorica segmentata), n inut de mar, cu capul neacoperit,

coiful purtndu-l atrnat pe umr; n mna stng in o suli,

de vrful creia sunt prinse bagajele elementare: sacul cu

alimente, gamelele, ustensilele de buctrie. Dup o mod

care ncepe s devin frecvent n vremea lui Traian, soldaii

din legiuni poart barb scurt. Din loc n loc, cu privirea

ntoars napoi, spre trup, apare cte un ofier, naintea lor,

n dreapta, merg purttorii steagurilor, unii ducnd un prapur

de pnz (vexillum), iar alii semnele distinctive ale diferitelor

uniti (signa, aquilae, phalerae, imagines). n fruntea

coloanei este artat un ofier superior.

n scena V apare un segment dintr-un al doilea pod de

vase, construit n acelai mod i situat n al doilea plan. Pe

acest pod se vd trecnd stegarii (signiferi) care, avnd capul

acoperit cu cte o blan de animal, de semnificaie sacr, poart

n mini acelai fel de nsemne ca i n imaginea precedent,

iar n fruntea lor se vede, de asemenea, un ofier superior.

nsemnele prezint detalii proprii cohortelor pretoriene.

Cum izvoarele scrise nu ne dau nici o indicaie asupra

modului cum a fost trecut Dunrea de ctre armata roman,

dublul pod artat pe Column a dat loc la nedumeriri. Ideea

c cele dou segmente ar aparine unuia i aceluiai pod

PE FRONTIER

(SCENELE I-III = 1-4, foto p. 115-116)

Istoria rzboaielor dacice reprezentate pe Column se

citete de la stnga la dreapta, ca o scriere, dar, contrar scrierii,

pornete de jos, imediat de deasupra bazei, pentru a se termina

sus, sub capitel. Extremitatea de jos, de la nceput, are forma

unui larg triunghi culcat, care, lrgindu-se treptat, abia dup ce

formeaz o spir n jurul Columnei face loc limii normale a

benzii sculptate. Pe aceast parte triunghiular se afl scenele

I-III, care reprezint malul drept al Dunrii, din Moesia

Superioar, din dreptul Banatului, prin urmare sunt nchipuite

ca vzute de la nord spre sud. Sub linia malului sunt reproduse

valurile fluviului, iar deasupra, n scena I, se vd nirate mai

nti dou turnuri romane simple de zid, pentru paz, nconjurate

cu palisade, apoi o stiv de lemne (brne depozitate spre a servi

la construcii militare), pe urm dou stoguri de fn conice,

formate, ca i azi, n jurul cte unui par. Erau proviziile unei

trupe de cavalerie. Dup aceea, apar trei turnuri nalte de paz

i de semnalizare, cu cte dou caturi, nconjurate cu cte o

palisad i avnd, pe balconul superior, cte o fclie. Distribuii

printre aceste turnuri, se vd patru soldai romani din trupele

auxiliare, narmai, n poziie de veghe.

Dup al treilea turn i dup ultimul din aceti soldai,

vine scena II, n care ondulaiile nchipuind apa Dunrii ocup

o lime mai mare, iar deasupra lor plutesc trei luntrii mari, n

dreptul unui castru de pe mal, nconjurat cu o palisad i avnd

n interior patru cldiri de zid, dintre care una are o faad cu

coloane. De pe una din nave soldaii descarc butoaie, coninnd

desigur vin i ulei. Pe alta se vd saci cu provizii, probabil gru

sau fin. Luntrele sunt prevzute cu cte o ram la pup.

Scena III arat, pe o nlime a malului, n fund, n

continuarea castrului din scena precedent, cldirile variate

i pitoreti ale unui ora. Printre case apar i arbori. n planul

nti, se vede ridicndu-se din valurile Dunrii trunchiul pe

jumtate nud al unui btrn cu barba i cu pletele ude, cu

capul ncununat de frunze de trestie. Este figura alegoric a

divinitii fluviului, zeul Danuvius, care, artat din profil,

privete spre importantul episod din scena urmtoare.

www.cimec.ro

23

Columna lui Traian Primul rzboi dacic al lui Traian

ntrerupt de un ostrov nu poate fi meninut, deoarece sunt

artate pe planuri diferite, iar ntre ele se vede apa Dunrii

curgnd. De altfel, un detaliu topografic lipsit de nsemntate,

ca interpunerea unui mic ostrov, nu putea s-l preocupe pe

artist, care cuta s comprime ct mai mult din ideile

exprimate.

Pe de alt parte, nu merit insisten nici eventuala

presupunere c armata roman ar fi trecut fluviul n acelai

moment i n acelai loc pe dou poduri alturate. Ar fi fost o

cheltuial considerabil de fore i de mijloace tehnice prin nimic

justificat care, chiar n cazul unei urgene extreme, n-ar fi dus

dect la un ctig de timp cu totul nensemnat. Dar aci nu era

deloc vorba de o atare urgen. Scenele urmtoare ne vor arta

c ptrunderea lui Traian n Dacia nu s-a fcut precipitat, ci,

dimpotriv, metodic i pe ndelete, cu frecvente solemniti

religioase, construcii de ceti, de drumuri, de poduri. Ct

vreme va strbate Banatul, dacii nu-l vor neliniti. Nu rmne

dect o singur explicaie a imaginii: sintetizarea trecerii

concomitente a Dunrii de ctre dou armate romane, la o

mare distan una de alta. Aceast interpretare, dat mai nti

de C. Cichorius i acceptat de majoritatea cercettorilor de

autoritate, corespunde excelent condiiilor strategice ale

primului rzboi dacic al lui Traian.

n adevr, dup cum dovedesc tirile epigrafice

referitoare la unitile care au participat la acest rzboi, forele

romane proveneau att din provinciile occidentale, ct i din

cele orientale. Ele au fost concentrate la Dunre n dou armate,

una n vest, condus de Q. Glitius Agricola, guvernatorul

Pannoniei, alta n est, pus sub comanda lui Manius Laberius

Maximus, guvernatorul Moesiei Inferioare. Ambele au naintat

spre locul de ntlnire, din direcii contrare, de-a lungul

Dunrii, trupele mergnd pe oselele de pe malul drept, iar

proviziile, bagajele i toate materialele grele fiind transportate

cu corbiile. Locul de ntlnire, ns, nu putea fi pe fluviu, ci

n interiorul Daciei deoarece cataractele de la Porile de Fier

i defileul Cazanelor mpiedicau circulaia. Printre stncile

cataractelor, navigaia unor nave ncrcate era imposibil, iar

pe oseaua din defileul Cazane, marul unei armate numeroase

ar fi fost riscant. Aceast osea, terminat cu un an mai nainte

(dup cum precizeaz Tabula Traiana pstrat pn azi la

faa locului), fusese construit n stnca pripor a malului drept,

cu o parte din limea sa spat n peretele muntelui, iar cu

cealalt adus, printr-un pod de lemn susinut cu brne oblice

prinse dedesubt, n acelai perete, deasupra apei. Urmele n

stnc ale acestui admirabil monument al hrniciei romane

puteau fi vzute nainte de formarea lacului de acumulare al

Sistemului hidroenergetic i de navigaie Porile de Fier.

Azi, ele sunt sub ap, iar Tabula Traiana a fost ridicat mai

sus, n acelai loc. Textul acestei inscripii ne spune:

Imp(erator) Caesar divi Nervae f(ilius),

Nerva Traianus Aug(ustus) Germ(anicus),

pontif(ex) maximus, trib(unicia) pot(estate) IIII,

pater patriae, co(n)s(ul) III,

montibus excisi[s] anco[ni]bus

sublatis via[m] f[ecit].

Adic: mpratul Caesar, fiu al divinului Nerva, Nerva

Traianus Germanicul, mare preot, avnd pentru a patra oar

puterea de tribun, printe al patriei, consul pentru a treia oar,

a fcut drumul, dup ce a tiat munii i a fixat console (H.

Dessau, Inscriptiones latinae selectae, 5863). Orict de iscusit

ar fi fost construit, un asemenea drum suspendat, care nc

nu-i fcuse ndeajuns proba soliditii, nu putea fi avut n

vedere n cadrul unei mari aciuni strategice. De aceea, se

impunea trecerea celor dou armate prin puncte diferite, pe la

extremitile acestei zone impracticabile. i astfel, pe la Lede-

rata a trecut numai armata din vest, pe care a luat-o sub

comanda sa nsui mpratul Traian, venit acolo de la Roma

cu cohortele pretoriene i cu garda personal de equites sing-

ulares. Cealalt armat, din est, a trebuit s treac fluviul puin

mai n aval de cataracte, la localitatea numit pe atunci Pontes

(puni), azi Kladovo, peste drum de Drobeta, azi Drobeta

Turnu Severin, adic pe locul unde civa ani mai trziu avea

s fie zidit celebrul pod statornic al lui Apollodor din Damasc.

Dup trecerea fluviului, aceast coloan a luat drumul

Banatului prin Dierna (Orova) i Ad Mediam (Mehadia),

continund prin pasul Damanei i pe la Cheile Teregovei,

spre a ajunge la Tibiscum (Caransebe), unde s-a ntlnit cu

coloana principal. Abia acolo, la intrarea n defileul Bistrei,

Traian i va avea n mn toate trupele pregtite pentru atacul

mpotriva lui Decebal.

n continuarea coloanei din vest, printre trupele care

au ajuns pe uscat, pe rmul dac al fluviului, se vd doi corniti

(cornicines) care sufl din trompete mari, curbe, i care poart

pe cap blnuri de animale, ca i stegarii, iar naintea lor merg

mai muli soldai narmai uor, dintre care unii duc cte un

cal de cpstru. Acetia sunt, fr ndoial, equites singulares.

Ofierul care se vede n fruntea lor i a crui figur nu mai

poate fi desluit, marmura fiind n acel loc spart, trebuie s

fie nsui Traian. Silueta, atitudinea i gestul personajului

corespund perfect reprezentrilor lui Traian din celelalte scene

ale reliefului. Chiar situarea sa n fruntea ntregii armate

pledeaz pentru aceast identificare. De altfel, mpratul, care

neaprat trebuia s figureze pe reprezentarea unui eveniment

att de important ca trecerea Dunrii, nu apare nicieri n alt

loc al scenei. Prezena lui este obligatoriu postulat i de

indicaiile referitoare la pretorieni i la equites singulares, i

unii i alii fcnd parte din garda care l nsoea pretutindeni.

O dat stabilit semnificaia dublului pod din scena V,

ea simboliznd trecerea a dou coloane de trupe la o mare

distan una de alta, se pune chestiunea precizrii celor dou

poduri diferite. Care e cel de la Lederata i care e cel de la

Pontes-Drobeta? Artnd trupe care trec Dunrea de la sud spre

nord, cu sudul n faa privitorului i cu estul la stnga sa,

imaginea ne oblig s situm primul pod n aval, deci la Pon-

tes-Drobeta, urmnd s identificm oraul de pe malul de sud,

din scena III, de pe poarta cruia ies trupele, cu Pontes. De

altfel, ar fi inutil de cutat vreo confirmare a acestei identificri

n cldirile reprezentate n scena III, deoarece pe Column

asemenea detalii sunt, din principiu, pur convenionale. Podul

de la Lederata e cel din al doilea plan, pe care trec signiferii

trupelor pretoriene, n continuarea clreilor desclecai care

l urmeaz pe Traian. Pentru ca nici o ndoial s nu mai ncap

www.cimec.ro

24

Columna lui Traian Primul rzboi dacic al lui Traian

n privina acestei continuiti, artistul a avut grij s-l arate pe

un ofier din coloan cu un picior pe pod, dar cu cellalt pe

uscat. Faptul c podul principal, pe care a trecut nsui mpratul,

este reprezentat n al doilea plan, nu nseamn dect o concesie

adus realitii geografice. Pentru ca scena s fie vzut din

fa nu era alt mijloc de a indica poziiile corelative ale celor

dou poduri. n schimb, pe cnd podul din primul plan, de la

Pontes-Drobeta, se oprete brusc, cellalt, de la Lederata, este

reprezentat pn la malul stng al fluviului, iar coloana care l

trece continu marul mai departe pe uscat, sugerndu-ne astfel

caracterul ei de element principal al povestirii din scenele

ulterioare. Lipsa Lederatei, ca i a legiunilor din aceast coloan,

care urmau dup pretorieni, constituie efectul unei economii

de spaiu, pe care analogia cu reprezentarea primei coloane o

compenseaz perfect. n definitiv, e vorba de acelai fel de

soldai i de o cetate similar, pe care dac artistul ar fi

reprezentat-o, cu risip de imagini, tot la detalii convenionale

ar fi recurs. Aceeai imagine de cetate e valabil pentru ambele

poduri i aceeai trup de soldai din legiuni e de neles pentru

ambele coloane. Trucul artistului de a fi comprimat dou

episoade analoge i concomitente ntr-o singur scen, fr a le

fi anulat diferena de poziie, se dovedete foarte ingenios,

constituind i un prim exemplu al limbajului lui ideografic.

Imaginea deteriorat a mpratului Traian, din fruntea

coloanei de la Lederata, care a trecut podul din al doilea plan,

se afl n dreptul unei tribune de zid, deasupra creia ade tot

Traian. Este o trecere pe nesimite la scena VI, cu alt subiect.

CONSI LI UL DE RZBOI

(SCENA VI = 6, foto p. 118)

Dup trecerea Dunrii pe la Lederata, coloana de vest

a armatei romane, comandat direct de mpratul Traian, i-a

strns rndurile pe malul stng al fluviului, n Banat, cantonnd

ntr-un castru cldit n prealabil, ca un cap de pod. Urmele

acestui castru au fost constatate la Palanca, ntre gura Caraului

i a Nerei. l amintete i numele localitii actuale, termenul

palanc nsemnnd ,,mprejmuire de cetate. Aci Traian a

inut un sfat cu statul su major, pentru a pune la punct planul

aciunilor urmtoare. Este episodul pe care l nfieaz scena

VI, venind imediat dup episodul trecerii Dunrii.

Deasupra unei tribune de zid, care trebuie presupus n

interiorul castrului menionat, se vede mpratul eznd pe o

sella curulis (scaun pliant rezervat nalilor magistrai ai

statului roman), ntre doi generali, care, de asemenea, sunt

aezai: cel din stnga mpratului, pe un scaun asemntor,

iar cellalt, din primul plan, pe un col proeminent din zidul

tribunei. Toate cele trei personaje sunt mbrcate n inut de

campanie, cu plato terminat pe umeri i pe poale prin fii

de piele. Personajul din dreapta lui Traian, aezat pe colul de

zid, trebuie s fie Claudius Livianus, comandantul grzii

pretoriene (praefectus praetorii), iar cellalt, care ade, ca i

mpratul, pe un scaun de suprem cinste, trebuie s fie un

fost consul, ceea ce s-ar potrivi att pentru Lucius Licinius

Sura, sfetnic intim al mpratului, ct i pentru Quintus Glitius

Agricola, guvernatorul consular al Pannoniei, comandantul

trupelor care l-au ateptat pe Traian la Lederata. Ultima

eventualitate pare mai potrivit cu semnificaia pur tehnic-

militar a episodului. n jurul lor stau n picioare numeroi

ofieri superiori, purtnd o pelerin (sagum) nnodat deasupra

pieptului. Printre ei, n spatele mpratului, se afl un lictor,

uor de recunoscut dup securea cu fascii pe care o ine pe

umr. E reprezentat unul singur, pentru economie de spaiu;

de fapt, n ocaziile solemne, tovria acestor personaje

tradiionale marca autoritatea magistrailor supremi ai

statului roman. Aici e vorba numai de autoritatea mpratului,

care, de altfel, era i consul, reales pentru a patra oar n

aceast demnitate de origine republican, tocmai n acel an,

la 1 ianuarie 101.

Care vor fi fost ncheierile consiliului de rzboi nu e

greu de bnuit. Ni le spun episoadele urmtoare: naintare pe

calea cea mai scurt pn la Tibiscum, unde se va face

jonciunea cu coloana plecat de la Drobeta, sub comanda

consularului Manius Laberius Maximus, guvernatorul Moesiei

Inferioare; apoi, cu totalitatea armatei, forarea defileului

Bistrei i a poziiei de la Tapae (Poarta de Fier a Transilvaniei)

i o ptrundere fulgertoare n masivul munilor Sarmi-

zegetusei, unde se va da forelor dace lovitura hotrtoare.

Tot n acest consiliu s-au luat msuri amnunite pentru

concretizarea itinerarului ce va fi parcurs de-a lungul vilor

Caraului i Cernovului i peste vile Brzavei i

Pogniului, pn la Timi, pe marginea de vest a munilor

Banatului, prin construirea sistematic, a unui drum militar

solid, pietruit, prevzut cu poduri, iar, din Ioc n loc, la etape

de cte o zi de mar, cam de 18 km, ntrit cu castre, care s

ofere trupelor adpost, odihn i provizii. Fiind vorba de calea

urmat de mprat, scenele Columnei se vor referi numai la

acest itinerar, dar nu e nici o ndoial c i coloana de est,

comandat de Laberius Maximus, a naintat concomitent, n

acelai mod, pe vile Cernei, Belarecii i Timiului,