Professional Documents

Culture Documents

National Council of Teachers of English

Uploaded by

emysamehOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

National Council of Teachers of English

Uploaded by

emysamehCopyright:

Available Formats

Development of Taste in Literature, III: Developing Taste in Literature in the Junior High

School

Author(s): Leonabd W. Joll

Source: Elementary English, Vol. 40, No. 2 (FEBRUARY, 1963), pp. 183-188, 217-218

Published by: National Council of Teachers of English

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41385437 .

Accessed: 19/09/2013 23:32

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

National Council of Teachers of English is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Elementary English.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Leonard W.

Joll

Development

of Taste in

Literature,

III:

Developing

Taste in Literature in

the Junior

High

School

Within the last two decades there has

been a

rapid growth

in

junior high

schools

in the United States. This has come about

as the result of two situations:

(1)

recent

interest in the

program

to be

provided

for

adolescent

youth,

and

(2)

an increase in

the school

population

with fewer

dropouts

yearly.

These

points

of view are substan-

tiated

by

Dr.

James

B. Conant in his

report

on Education in the

Junior

High

School

Years.

(1)

At the

present time, many

educators be-

lieve that the

junior high

school

period

is

the most

important

one in the total devel-

opment

of the child. These are the

years

when the

pupils

are neither children nor

adults. If

they attempt

to act like

grown-

ups they

are told

they

have a lot to

learn;

if

they pursue

activities of

children, they

are

frequently

told to act their

age.

If we

expect

to

develop

a taste for literature in

this

group,

then the

following topics

are

important

for consideration.

1. Studies related to the

development

of

literary

taste in

junior high

school students.

2.

Promising practices being

used to de-

velop literary

tastes at this level.

Studies Related to the

Development

of

Literary

Taste in

Junior High

School

Students

Research in

regard

to children's interests

has been a favorite

pursuit

for

many years.

Melbro

(12) points

out in A Review

of

the

Literature on Children's Interests

reported

in the Twelfth Yearbook of the California

Elementary

School

Principal's

Association,

that the 1930's

may

well be marked as the

period

in which children's interests were

discovered.

During

the

period

of

1930-1940,

a total of 362 articles on children's interests

were

reported

in Educational Index and

Psychological

Abstracts. Studies of child-

ren's interests and summaries of such stud-

ies continue to

appear frequently.

While interest studies of children have

been

numerous,

there has been a

great

dearth of research in

regard

to the devel-

opment

of

literary

taste at the

junior high

school level. There was some interest in

this

topic

as a

subject

of

investigation

in

the 1930's and

early

1940's.

Very

little re-

search

directly

related to the

development

of taste has been conducted since that time.

The few studies

bearing

on this

topic

which

could be located are summarized below.

Two studies were concerned with the

development

of taste in and

appreciation

of

poetry. McMurry (11)

conducted a

study

with two

groups

of

pupils

who were

in the first semester of seventh

grade.

Her

purpose

was to find which of two methods

of

teaching poetry

was most effective- the

teaching

of

poetry by placing special

em-

phasis

on

poetic qualities

or the

teaching

of

poetry by

a method in which no

attempt

Dr.

Joll

is Director of

English

in

Secondary

Schools,

State

Department

of

Education,

Hart-

ford,

Connecticut. This is the third and final

article in this series. The three

articles, plus

one

concerned with taste in literature in the

high

school,

will

appear

in a Research Bulletin of the

National Conference on Research in

English.

183

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

184 Elementary English

was made to

bring

the child to a realization

of

poetic

values.

McMurry's

conclusions were as follows:

(a)

At the

beginning

of the

study

there

was little or no

appreciable

difference be-

tween the

groups

as to

ability

to

distinguish

between

good poetry

and verse which was

lacking

in

poetic values; (b)

the final test

indicated that the children who had been

taught poetry regularly

with

emphasis

on

poetic qualities

showed a

greater growth

in the

ability

to

judge poetry

than did those

who had not been

taught poetry

with a

systematic

reference to basic

poetic

values;

(c)

oral and written

expressions

of the

pupils engaging

in this

study

revealed the

fact that the

group

that studied the

poetic

principles gained

a fuller

meaning

and a

deeper appreciation

of

poetry

than did the

other class.

Woesner

(17)

also conducted a

study

having

to do with the

development

of

taste at the

junior high

school level. Her

purpose

was to ascertain if

writing

imita-

tions of

poetry

was effective in

developing

appreciation.

Students in the

experimental

group

chose their own

subjects

for

writing

imitations of

poems

to be read

by

the

group.

In order to write the imitations students

had to

study rime, rhythm, imagery, pe-

culiarities of

language,

and stanza form of

the

original poems.

The

investigator

con-

cluded that imitation used as a means of

teaching appreciation

of

poetry

is not su-

perior

to the conventional methods. In dis-

cussing

the limitations of the

study

she

makes these

very important

observations:

". . .there is a real

difficulty

in

determining

when

appreciation

has been achieved.

. . .It seems evident that more accurate and

more

comprehensive

tests for the measure-

ment of

appreciation

of

poetry

should be

devised."

Some studies have

emphasized

that those

who would

develop literary

taste should

start with the individual child's level of

development

rather than

expecting

all

children in a certain

grade

to read and en-

joy

the same books.

McCullough (10)

in

her article titled "What Is a Good Book for

a Ninth Grader?" summarized the results

of her

study

with one hundred fourteen-

year-old

students. In her conclusion this

investigator pointed

out that teachers of

English

should train their

pupils

to

recog-

nize

good

books

by starting

at the child's

level of

literary appreciation.

Norvell

(13) reported

the results of a

controlled

experiment

concerned with wide

individual

reading compared

with the tra-

ditional

plan

of

studying

literature. His

data showed

advantages

of a vitalized

pro-

gram

of wide

reading

of literature with

adaptations

to individual differences as

contrasted with the traditional

plan

of

having

all members of a class

study

des-

ignated

selections.

Herman

(6)

made a

questionnaire study

of over 1900 adolescents which led to this

conclusion: "the course of

study

in

reading

for

pleasure

and

appreciation

in the

junior

high

school must be based on the nature

of the child himself rather than on what

he

may

be in the future."

It is

generally

conceded that the first

step

in

developing

taste in literature is to

find out where the individual is and to

proceed

from that

point.

In this connection

a word

might

be said in

regard

to the

danger

of

applying

broad

generalizations

resulting

from studies of children's inter-

ests. Melbro

(12)

in consideration of in-

dividual differences concluded at the end

of his review

that,

on the

whole,

the numer-

ous studies which

attempt

to locate

pupil

interests in terms of

subject preferences

are

unproductive.

The writer

(8)

concluded as

a result of

using

the forced-choice interest

inventory technique,

that the

employment

of an interest

inventory

would

probably

prove unsatisfactory

in

determining

the

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Developing Taste in Literature in the

Junior

High School 185

areas of interest in literature for

junior

high

students.

The

difficulty

of

literary

selections as

related to the

development

of taste has

been the

subject

of some studies. These

studies are

especially significant,

for

surely

we cannot

expect junior high

school stu-

dents to

develop

taste for literature which

is too difficult for them to read.

Figurei (3)

estimated the

difficulty

of

certain classics used in ninth

grade

litera-

ture classes and

compared

them with

grade

scores in

reading

of 168

ninth-grade pupils.

He found that

many

of the selections were

much too difficult for a

surprisingly large

proportion

of the

pupils.

His conclusion

emphasized

the fact that "custom and tra-

dition are not in themselves

necessarily

good

criteria for

determining

the

grade

allocation of

reading

material."

Jackman (7)

conducted a

study resulting

in evidence to the effect that there are

many

factors other than

vocabulary

and

sentence structure which determine the

maturity

of the content of a

selection,

such

as

"plot complexity,

number of

characters,

fineness of character

delineation, philo-

sophical concepts presented

or

implied,

use of

figurative expressions,

and a

gen-

erally

distinctive

style/'

This

investigator

is sound in

maintaining

that the

maturity

level of material cannot be

satisfactorily

measured

through

structural items

only.

Some studies have been conducted with

junior high

students in

regard

to the de-

velopment

of taste in

magazine reading.

La Brant and Heller's

Study (9)

in an

experimental

school resulted in a

very

con-

structive conclusion. This conclusion was

that the solution of the

"problem

of teach-

ing pupils

to read

good magazines

lies in

making

the

magazines

available in

quan-

tity,

in

providing

situations where

they

can

be read

profitably,

and in

allowing

leisure

for their use."

Williams

(16)

conducted a

study

of

magazine reading

in schools in

England.

Other studies have shown that the

reading

interests and tastes of

junior high

school

students in

England

are

very

similar to

those of American children at this

level,

so Williams' conclusions are

pertinent

to

the discussion. This

investigator

stated that

(

1

)

"the

young

adolescent who reads at all

may

read

anything

which comes his or her

way,

and

(2)

"that

literary

taste has not

fully

matured when the school

leaving age

is reached." In addition Williams drew two

other conclusions which are

significant

from the

standpoint

of

developing

tastes.

These conclusions were:

First,

it does not

appear

that schools and educationists are

making

"the fullest use of

opportunities

for

introducing

the adolescent to worthwhile

reading

matter . .

.; second,

a

great

re-

serve of

reading energy

remains

untapped

which could be used to raise the cultural

level of children who are

approaching

the

age

at which

(for many

of

them)

their

formal education is about to close."

Unfortunately

this is about all that can

be

presented

in the

way

of research re-

views on

developing literary

tastes in

junior

high

school students. The remainder of this

account will be devoted to

empirical

dis-

cussion based on the

experiences

of suc-

cessful teachers of literature.

Promising

Practices in

Developing Literary

Tastes in the

Junior High

School

Did

you

ever see a

group

of children

who did not

enjoy listening

to a

good

story?

Children at all

ages

like to have

stories read to them

provided

the material

is suitable and well read. Teachers at

every

level should read to their students. These

readings

should be

supplemented by good

recordings,

if

possible,

and then followed

by lively

class discussion.

Junior high

school teachers

might

well take a lesson

from

kindergarten

and

first-grade

teachers.

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

186 Elementary English

Not

only

do children in the

grades

en-

joy discussing

a

story

but

they frequently

like to act out

parts

of the

story.

On several

occasions the writer has observed

Phyllis

Fenner demonstrate with children whom

she had never seen. First she reads or tells

them a

story

and then she has the

story

acted out. Once into the

story

the children

are

always

most reluctant to

stop discussing

or

enacting

it. Several teachers have used

this

plan successfully

with

junior high

school students.

Poetry

often

presents

a

challenge

to

junior high

teachers and is

apt

to

bring

forth

groans

from the

pupils.

Harvi Fiari

(4) reports

an

interesting procedure.

He

believes that teachers shouldn't

just

throw

poetry

at students but that

they

should first

get

them into the mood. He used

laughter

to

get

his students started on the road to a

greater understanding

of what the

poets

of humorous

poems

were

trying

to com-

municate. He

concluded,

"Once the stu-

dents are on that

road,

I find it easier to

move into more difficult

poetry

and to deal

with the

techniques

of the

poet."

Not

long ago

the writer visited a fresh-

man

English

class at the

High

School in

Wayland,

Massachusetts. Students in the

class were asked to

prepare

to read

any

poems they

desired. Each student

might

select one or several

poems

to read and he

might

also choose an

appropriate

musical

background

to

accompany

his

reading.

The

students

voluntary

comments indicate their

reactions to this

activity:

"We never

thought

poetry

could be so much fun." "It

helps

a

lot to feel the

rhythm

of the

poem

when

you

read it to music." "I never

thought

poetry

could be such

enjoyable reading."

A teacher in a

seventh-grade

class at the

Hatton School in

Southington,

Connecticut

made a

daily practice

of

reading

a short

poem

to the class as

part

of the

morning

exercises. One

morning

he omitted the

poem.

Several members of the class asked

if he had

forgotten

it. His

reply

was that

he was

running

out of

poems

and needed

some

help.

The next

day many

contribu-

tions were

brought

in and read

by

mem-

bers of the class. These

readings

were

taped.

The students listened to their own

recordings

and then asked if

they might

record

again

after

they

had had time to

make better

preparation. Poetry

came alive

in this class!

Did

you

ever

try

to teach

poetry

to a

group

of

boys

in a vocational

program?

"Poetry

for the Reluctant" as

reported by

Snouff er and Rinehard

(

15

)

offers food for

thought.

To

paraphrase

the authors of this

article,

"God must have loved the reluctant

student,

as it

appears

he made so

many

of

them." In the situation described

by

these

authors careful

planning

had been done.

An attractive theme was selected: "A

Typical

American Scene." The bulletin

board was

put

to extensive use. As

poems

were

read,

the

boys

in the class volunteered

appropriate

titles and

greatly vying

with

one another to see whose title was most

closely

akin to that of the author. The

writing

of

poems

was a real

challenge

and

one that

paid

off. The

development

of a

collection of

original poems

entitled,

"Ran-

dom

Thoughts"

was the final

activity.

Not

only

did these

boys

read

poetry

and

enjoy

it,

but

they

also wrote

poems. Probably

many

of them will continue to read

poetry

the rest of their lives.

Norvell

(14)

has made these observa-

tions; (1)

to "read with ease" does not im-

ply capacity

to read the

recondite; (2)

children do not read

widely enough

to

transform a chore into true

recreation;

and

(3)

too often children's well wishers set

up

blocks

by insisting "only

the best of the

best." Norvell further

points

out that it is

not

enough

to know that a book has a

satisfactory rating by

authorities but to

know also how it is rated

by boys

and

girls.

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Developing Taste in Literature in the

Junior

High School 187

A careful examination of

many

courses

of

study

in

English

for

grade

seven

through

nine indicates that a certain amount of

stress is

placed

in

making

book

reports.

There is

nothing wrong

with book

reports,

the harm seems to come in the

way

in

which

they

are handled. The writer has

talked with excellent students who have

bragged

that

they always

handed in their

book

reports

on time but had never read

a book.

They

had

carefully gone

over the

content on the

jackets

of the books. From

these sources

they

had obtained

enough

information to

prepare

their book

reports

with never a failure.

In contrast to

this,

the writer would like

to mention an incident that took

place

in

a classroom visited two

years ago.

In this

class no book

reports

were

required.

Be-

fore the discussion started the teacher

asked the members of the class what

they

had been

reading.

After

noting

several

titles

given by

each

student,

the discussion

began.

Before

long

one

boy

raised his hand.

"I do not

agree

with the statements of the

speaker,"

he said.

"What are

your

reasons for

disagree-

ment?" asked the teacher. The reaction

was obvious. The

boy

had read the books

he had listed and

many

more which had

not been mentioned

previously.

Not

only

had he read these books but he knew them

so well that he could call

upon

their con-

tent to back

up

his reasons for

disagree-

ment. This is an

example

of a more func-

tional

way

of

giving

book

reports.

Mrs.

Kathryn

Roberts at the Woodstock

Academy

in

Woodstock,

Connecticut in-

troduces a

newspaper

unit

along

with the

literature unit. Various characters are in-

jected

into

daily

news columns as if the

story

were

taking place currently.

The

results of this

practice

is that the

pupils

are

far more critical of the entire

story

and

are

greatly

aided in their own

interpreta-

tions,

Symposia

and

panel

discussions often

help

to liven

up

interest in

good

literature.

In one

seventh-grade

class where the read-

ing program

is

individualized,

there is a

preferred

list. This is made

up

of books

that have been

reported orally

to the class.

The

presentations

are so well done that

many

of the students wish to read these

stories,

and therefore the books must be

reserved and a time limit

put

on the

length

of time that

pupil

can

keep

them.

A teacher in one ninth

grade frequently

opens

the literature

period

with a conver-

sation. She will address a member of the

class as if he were a character in a book

that has been read. Th student then re-

sponds

as the character

might

have

done;

then if he

wishes,

he

may

address other

members of the class as other characters

in the same

story. Frequently

the student

may

be called

upon

to initiate a conversa-

tion. This

activity

has

proved

to be most

enjoyable

and is

just

another situation in

which literature is made to live.

Charles M. DeWitt

(2) reports

that in

his classes he has a "Hit Parade of Books."

Once

every

two weeks a

poll

is taken of

the books read

by

the class. The ten books

having

the

highest

number of readers are

placed

on the "Hit Parade." A certain

number of books that received a substantial

number of votes but not a sufficient num-

ber to make them "hit"

books,

are listed

as "Books to Be Boosted." DeWitt finds

that

by using

this

program,

and

by sup-

plementing

it with a

variety

of lesser

library activities,

the entire class reads

and

enjoys

more

good

books.

All of the

practices

described in this

article have involved students in their ac-

tive use of books.

They

have been sur-

rounded with as

many good

books as

possible. They

have shared their

experi-

ences with each other.

They

have read

more and better books because

they

were

available,

and because

they

were

presented

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

188 Elementary English

to them

by

enthusiastic teachers and

espe-

cially by

their fellow classmates.

Teachers and

pupils

mentioned in this

discussion did not have the benefit of much

research in

developing

taste in literature

for

very

little research has been done on

this

subject.

Nevertheless the methods

described

appear

to be sound and it is

reasonable to assume that

through

such

activities students learn to

enjoy

literature

and to discriminate between the best in

literature and

poorly

written material with

which

many

of them are surrounded. Such

experiences

should result in the

develop-

ment and refinement of

literary

taste. It

would be

good, however,

if the

promising

procedures being

used

by many

of our

fine teachers of literature

might

be sub-

jected

to

experimental study.

Then we

would know for sure which ones are effec-

tive,

and which ones are not.

Summary

1.

Junior high

school students are in a

formative

age.

It is

particularly important

that teachers should

guide

their

reading

tastes to

higher

levels

during

this

period.

2. A

study

of the level of tastes at which

each individual has arrived is the first

step

for a teacher to take in

helping

a student

to reach the next

"rung

on the ladder."

3.

Many promising practices

are

being

used

currently by junior high

school teach-

ers in

developing

tastes in literature.

4. There is a

regrettable paucity

of re-

search in

regard

to the

development

of

literary

taste at the

junior high

school level.

5. It is

urgently suggested

that teachers

and

many

others interested in research

direct their

energies

in the near future

toward

conducting

scientific studies in this

much

neglected

but

extremely significant

area of

development

during

the adolescent

years,

Bibliography

1.

Conant, James .,

Education in the

Junior

High

School Years.

Princeton,

N.

J.:

Edu-

cational

Testing Service,

1960.

2.

DeWitt,

Charles

M., "Stimulating

Leisure

Reading," Elementary English ,

30

(Decem-

ber, 1953),

514-515.

3.

Figurei, J. Allen,

"Relative

Difficulty

of Read-

ing

Material for Ninth Grade

Literature,"

Pittsburgh

Schools

,

16

( January-Februarv,

1942),

125-138.

4.

Firari, Harvey,

"Out of Chaos

-

Learning/'

English Journal , 48, (May, 1959),

262-265.

5.

Hermans,

Mable

C., "Utilizing

Adolescent

Interests,"

Los

Angeles

Educational Re-

search Bulletin

,

10

(May-June, 1931),

2-29.

6.

Hockett, John A.,

"Variations in

Reading

In-

terests in Different School

Grades,"

Chil-

dren's

Interests,

95-100.

Twelfth

Yearbook

of

the

California Elementary

School

Principals'

Association

, Oakland,

California: California

Elementary

School

Principals' Association,

1940.

7.

Jackman,

Mabel

E.,

"The Relation Between

Maturity

of Content and

Simplicity

of

Style

in Selected Books of

Fiction," Library

Quarterly ,

11

(July, 1941),

302-327.

8.

Joll,

Leonard

W.,

Connecticut Interest In-

ventory.

Part of Doctoral

Study. Temple

University, Philadelphia,

1953.

9. La

Brant,

Lou

L.,

and Freida M.

Heller,

Magazine Reading

in an

Experimental

School," Library Journal ,

41

(March 15,

1936),

213-217.

10.

McCullough, Constance,

"What Is a Good

Book to a Ninth Grader?"

English Journal ,

25

(May, 1936),

381-387.

11.

McMurry, Malissa,

Contrasted

Techniques

in

the

Teaching of

Poetic Values in the Junior

High

School.

Unpublished

Master of Arts

Thesis,

Colorado State

College

of

Education,

Greeley, Colorado,

1926.

12.

Melbro, Irving R.,

"A Review of the Litera-

ture on Children's

Interests," Twelfth

Year-

book

of

the

California Elementary

School

Principals

'

Association

,

12

(1940),

95-100.

13.

Norvell, George W.,

"Wide Individual Read-

ing Compared

with the Traditional Plan of

Studying Literature,"

School Review

,

49

(October, 1941),

603-613.

14.

Norvell, George W.,

The

Reading

Interests

of Young People.

Boston: D. C. Heath

Co.,

1950, pp.

30-39.

15.

Snouffer, Mary

S. and Patricia

Rinehard,

"Poetry

for the

Reluctant," English Journal ,

70

(January, 1961),

44-46.

(Continued

on

page 217)

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Books for Children 217

gestion

that the whole

thing

is the result

of machine translation.

One statement can be made with con-

siderable

certainty-

no American

juvenile

editor

got

his hands on either the finished

manuscript

or the

layout.

If he

had,

the

results would be seen in a better book.

The

only tragedy

of this book is that so

many

children will be

disappointed.

For

the

buyers

of books are

adults,

and adults

tend to

buy picture-books

after consider-

ing only

the title and the illustrations. No

one can

dispute

the fact that the title

promises important

content,

nor can

they

fault the beautiful illustrations.

Life Story.

Written and illustrated

by

Virginia

Lee Burton.

Houghton Mifflin,

1962.

$5.00.

(6-12)

Five dollars is a lot to

pay

for a

picture-

story

book? Not for this one!

Who,

beside

Robert

McCloskey

and Marcia Brown can

win a second Caldecott Medal?

Virginia

Lee Burton should!

Life Story

is an abso-

lutely exquisite

book. It bears the indelible

touch of a

truly gifted

author-illustyator.

Its

handsome black cover with its

gjold

em-

bossed

sun,

its solid black front

endpapers

and its solid

yellow concluding end-papers

symbolize

the darkness from whence the

earth came and the

light

toward which all

mankind

fervently hopes

it is headed. Be-

tween these

end-papers

lies the

story

of

life,

from the earth's

beginning

to

today's

tick of the clock.

Burton has chosen to set her illustrated

account under a

proscenium

arch. Each

of the

thirty-five

scenes,

as set forth in

the

playbill

introduction,

is narrated

by

one of six

people:

"An

Astronomer,

a

Geologist,

a

Paleontologist,

a

Historian,

a

Grandmother and VIRGINIA LEE BUR-

TON. It is little short of a miracle that so

vast and

complicated

a

subject

could

pos-

sibly

be

presented

with skill

enough

to

make it understandable to the reader. But

Burton has done it.

No amount of

scholarly

research could

pay

such handsome dividends without be-

ing

based

upon

a

seemingly

innate

feeling

for the vastness of time and the

importance

of life. Nor could such a work be ac-

complished

without

mastery

of written

word and

painted

line.

Every

child who reads this book will be

richer for

having

had the

experience.

He

will be enfolded in Burton's

sweeping

arcs

and

descending spirals.

He will come

away

from the

reading feeling

the

meaning

of

Miss Burton's

lyric

account of her life.

(Continued from page 188)

16.

Williams,

A.

R.,

"The

Magazine Reading

of

Secondary

School

Children,"

British

Journal

of

Educational

Psychology,

21

(November,

1951),

186-198.

17.

Woesner,

Inez

Estelle,

A

Study of

the

Ef-

fectiveness of

Imitation as a Means

of

De-

veloping Appreciation

in

Poetry , Unpublished

Master of Arts

Thesis, University

of

Washing-

ton, Seattle, Washington,

1936.

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ATTENTION

EDUCATORS

Let us

help you plan

the most

economical vacation or

study

program possible.

As fellow educators we un-

derstand

your problems

and in-

terests.

wi SeiiUaeA. 91&

VACATION PLANNING

Low cost travel

arrangements

here

and abroad.

HOME LEASING-

EXCHANGE

Exchange

or lease homes with

fellow educators in other locales for

vacation or

study purposes.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE-

VISITS

Stay

in the homes of

foreign

edu-

cators on

your

next

trip

abroad.

MoHtf

Uteb Seuice.

Send for our brochure

today.

Address:

HOMEX

Enterprises

Box 582 MPO

Niagara Falls,

N. Y.

Please send information about the

HOMEX Services.

Name

Address

City

State

218

(Continued from page 182)

sponse.

Unskilled

handling

of children's

feelings

can be

dangerous.

Learning

is a

feeling

as well as a mental

process.

When the "six" is

helped

to under-

stand the

stirrings

within

himself,

and

grad-

ually

masters his

"growing up"

fears and

impulses,

he can stride some

v

days

like a

giant-

both at home and at school.

(Continued from page 193)

smell,

touch and taste have to be

smuggled

in the back

way,

because

they

don't fit

the master

plan.

Non-verbal communication has been

generally ignored

or

rejected

in American

education. It should not be

taught

as a

separate subject

or

skill,

like

reading

or

speaking.

But,

it should be

explored

as a

fifth area of

language

arts. It should be

sufficiently

understood so that teachers

will

accept

its

unique

values and sensitive

relations to

personality development.

It

should be understood as an area where

much

creativity

can be

developed.

It

should be

recognized

for its close ties to

the social and natural

experiences

of chil-

dren. It should be

respected

for the emo-

tional tones it

imparts

to the whole area

of

language

arts. It should be understood

as a source of

learning

in this

developing

era of audio-visual

techniques.

Non-verbal

communication is the

"sensing"

level for

speaking

and

listening,

for

reading

and

writing.

In that role it

helps

to

unify

the

language

arts.

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 23:32:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Grammar and Vocabulary Test for Unit 1Document3 pagesGrammar and Vocabulary Test for Unit 1sara82% (33)

- Vocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test ADocument5 pagesVocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test Aemysameh100% (5)

- Grammar and Vocabulary TestDocument4 pagesGrammar and Vocabulary Testemysameh100% (2)

- Vocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test BDocument5 pagesVocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test Bemysameh50% (4)

- Additional ProblemDocument3 pagesAdditional ProblemthanhvanngocphamNo ratings yet

- A Stranger in Strange LandsDocument34 pagesA Stranger in Strange LandsCjbrhetNo ratings yet

- Workbook Unit 4Document1 pageWorkbook Unit 4BridgethNo ratings yet

- Are Comics Effective Materials For Teaching EllsDocument12 pagesAre Comics Effective Materials For Teaching Ellsjavier_meaNo ratings yet

- Materi Introduction To LiteratureDocument7 pagesMateri Introduction To LiteratureYundayana RNNo ratings yet

- 3 Reading Needs Assessment and Survey 810Document11 pages3 Reading Needs Assessment and Survey 810elaineshelburneNo ratings yet

- Improving Reading Attitudes in High School StudentsDocument25 pagesImproving Reading Attitudes in High School StudentsRIVAYNE ChannelNo ratings yet

- HeablerDocument5 pagesHeablerMaria Ronalyn Deguinion AcangNo ratings yet

- Running Header: Graphic Novels To Build ComprehensionDocument12 pagesRunning Header: Graphic Novels To Build Comprehensionapi-288613356No ratings yet

- Using Young Adult Literature to Increase Student Success and Teach MulticulturalismDocument59 pagesUsing Young Adult Literature to Increase Student Success and Teach MulticulturalismSmite GraNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago Press The Elementary School JournalDocument25 pagesThe University of Chicago Press The Elementary School JournalNun-Qi YashinuyNo ratings yet

- Towards Effective Values of Teaching Literature ToDocument6 pagesTowards Effective Values of Teaching Literature ToCherise SpiteriNo ratings yet

- Encouraging Critical LiteracyDocument12 pagesEncouraging Critical LiteracyBadaruddin SappaNo ratings yet

- Writing Annotated BibliographiesDocument2 pagesWriting Annotated BibliographiesNancy M. BaileyNo ratings yet

- Teaching English As A Foreign Language Through Friendly Literature For Young LearnersDocument9 pagesTeaching English As A Foreign Language Through Friendly Literature For Young LearnersAustin Macauley Publishers Ltd.No ratings yet

- MMSD Classroom Action Research Vol. 2010 Adolescent Literacy InterventionsDocument28 pagesMMSD Classroom Action Research Vol. 2010 Adolescent Literacy InterventionsAulia DhichadherNo ratings yet

- Bilingual in Early Literacy PDFDocument10 pagesBilingual in Early Literacy PDFsavemydaysNo ratings yet

- Viability of Poetry in Acquiring Reading SkillsDocument7 pagesViability of Poetry in Acquiring Reading SkillsGiselle MelendresNo ratings yet

- A Coorelational Study On How Reading 1Document50 pagesA Coorelational Study On How Reading 1mariposa rosaNo ratings yet

- Wright - Assignment 5 - Research On Visual and Media LiteracyDocument8 pagesWright - Assignment 5 - Research On Visual and Media Literacyapi-306943296No ratings yet

- Understanding Poetry: Perceived Difficulties and Strategies of CTE Language Major StudentsDocument49 pagesUnderstanding Poetry: Perceived Difficulties and Strategies of CTE Language Major StudentsZinnia Jane FabreNo ratings yet

- Litaphndbk 2Document66 pagesLitaphndbk 2Uditha Melan100% (2)

- Literature Circles: Acquiring Language Through CollaborationDocument13 pagesLiterature Circles: Acquiring Language Through CollaborationkevinmmaherNo ratings yet

- Mental. Many Learners Wish To Acquire Integrate Themselves Into The Culture of The New LanDocument13 pagesMental. Many Learners Wish To Acquire Integrate Themselves Into The Culture of The New LanNada AbdulRedhaaNo ratings yet

- Children LiteratureDocument14 pagesChildren LiteratureHafiezul HassanNo ratings yet

- Using Comic Strip Stories to Teach VocabularyDocument12 pagesUsing Comic Strip Stories to Teach VocabularySandy RodriguezNo ratings yet

- jennie-research (1)Document22 pagesjennie-research (1)Jennifer B. Alfaro-TalidongNo ratings yet

- Thesis Is Real FinalDocument33 pagesThesis Is Real FinalVincent ParungaoNo ratings yet

- Final ThesisDocument101 pagesFinal ThesisHazel Sabado DelrosarioNo ratings yet

- Poetry LessonDocument17 pagesPoetry Lessonapi-416181000No ratings yet

- The Importance of Teaching English Literature to ChildrenDocument56 pagesThe Importance of Teaching English Literature to ChildrenHector PetersenNo ratings yet

- Wddim EditedDocument10 pagesWddim Editedapi-355733870No ratings yet

- Litaphndbk1 PDFDocument72 pagesLitaphndbk1 PDFpdkprabhath_66619207No ratings yet

- Specification 2nd Sem Lit 202Document7 pagesSpecification 2nd Sem Lit 202Richard BañezNo ratings yet

- Jac Harris Assignment 7 Article 1 SummaryDocument3 pagesJac Harris Assignment 7 Article 1 Summaryapi-335579446No ratings yet

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument12 pagesInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelNo ratings yet

- Approaches to Comparative Mother-Tongue Education (CMEDocument18 pagesApproaches to Comparative Mother-Tongue Education (CMERoxana GhiațăuNo ratings yet

- Literature in Teaching English As A Second LanguageDocument27 pagesLiterature in Teaching English As A Second LanguageRidawati LimpuNo ratings yet

- Pleasure Reading Impact on Student PerformanceDocument9 pagesPleasure Reading Impact on Student PerformanceNELSONNo ratings yet

- A ReiterDocument10 pagesA ReiterEsteban VélihNo ratings yet

- Factors Militating Against Proper Teaching and Learning of Literature in English in Senior Secondary SchoolsDocument7 pagesFactors Militating Against Proper Teaching and Learning of Literature in English in Senior Secondary SchoolsDaniel ObasiNo ratings yet

- Teaching of GrammarDocument11 pagesTeaching of GrammarMilly Hafizah Mohd Kanafia100% (1)

- Storytelling As A Tool For English Classes With Young Learners: A Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesStorytelling As A Tool For English Classes With Young Learners: A Literature ReviewGenoveva Sagurie SeguelNo ratings yet

- "I Always Need A Translation To Read": Malay-English Bilingual Children's Reading PreferencesDocument22 pages"I Always Need A Translation To Read": Malay-English Bilingual Children's Reading PreferencesNur AmaniNo ratings yet

- What Do Our 17-Year-Olds Know: A Report on the First National Assessment of History and LiteratureFrom EverandWhat Do Our 17-Year-Olds Know: A Report on the First National Assessment of History and LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Critical Literacy Strategies Through The Use of MusDocument82 pagesIncorporating Critical Literacy Strategies Through The Use of MusAbdul AjizNo ratings yet

- Dexis and WritingDocument15 pagesDexis and WritingSara EldalyNo ratings yet

- Criteria for Selecting Literary Texts in ELTDocument14 pagesCriteria for Selecting Literary Texts in ELTLita Trii LestariNo ratings yet

- Arjen de Korte Literature and Language Learning PDFDocument5 pagesArjen de Korte Literature and Language Learning PDFdexcrsNo ratings yet

- Literature in Language Teaching and LearningDocument6 pagesLiterature in Language Teaching and LearningecoNo ratings yet

- Clandfield - Literature in The ClassroomDocument4 pagesClandfield - Literature in The Classroompamela vietriNo ratings yet

- Title - Male Students' Declining Interest in English Literature-PowepointDocument41 pagesTitle - Male Students' Declining Interest in English Literature-PowepointRichardoBrandonNo ratings yet

- EFL Students' Attitudes toward Literature and Instructional MethodsDocument14 pagesEFL Students' Attitudes toward Literature and Instructional Methods013AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Three Articles That Pertain To Graphic Novels in The ClassroomDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Three Articles That Pertain To Graphic Novels in The Classroomapi-354545316No ratings yet

- The Advantages of Literature To LearnersDocument7 pagesThe Advantages of Literature To LearnersNicole RapaNo ratings yet

- Full ArtikelDocument10 pagesFull ArtikelMohd Zahren ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Poetry in An EFL - ESL Class - An Integrative and Communicative ApproachDocument10 pagesTeaching Poetry in An EFL - ESL Class - An Integrative and Communicative ApproachIndah Mala HikmaNo ratings yet

- Research Review 3Document15 pagesResearch Review 3Dianne BartolomeNo ratings yet

- 26-67-5-PBDocument14 pages26-67-5-PBCumi PayaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Wa Educ 5281Document4 pagesUnit 2 Wa Educ 5281TomNo ratings yet

- How Short Stories Can Boost Junior High Reading SkillsDocument7 pagesHow Short Stories Can Boost Junior High Reading Skillsmdc_fastNo ratings yet

- 1840-Article Text-5281-1-10-20150122Document11 pages1840-Article Text-5281-1-10-20150122emysamehNo ratings yet

- New ENGLISH PLACEMENT SAMPLE QUESTIONS PDFDocument4 pagesNew ENGLISH PLACEMENT SAMPLE QUESTIONS PDFIsaac CordovaNo ratings yet

- Engagement Inventory Teacher RecordDocument1 pageEngagement Inventory Teacher Recordapi-369324244No ratings yet

- Relationship Between Narrative and EngagementDocument54 pagesRelationship Between Narrative and EngagementemysamehNo ratings yet

- Nutrition BookDocument5 pagesNutrition Bookemysameh100% (1)

- Using Narrative Distance To Invite Transformative Learning ExperiencesDocument18 pagesUsing Narrative Distance To Invite Transformative Learning ExperiencesemysamehNo ratings yet

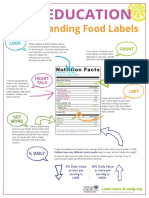

- Label ReadingDocument4 pagesLabel ReadingemysamehNo ratings yet

- Nutrition LabelDocument2 pagesNutrition LabelemysamehNo ratings yet

- Test - Infotech English For Computer Users Work Book - Unit 4 - QuizletDocument4 pagesTest - Infotech English For Computer Users Work Book - Unit 4 - QuizletemysamehNo ratings yet

- Understanding nutrition labels and daily valuesDocument2 pagesUnderstanding nutrition labels and daily valuesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Authorizing Readers Resistance and Respect in Teaching Literary Reading ComprehensionDocument2 pagesAuthorizing Readers Resistance and Respect in Teaching Literary Reading ComprehensionemysamehNo ratings yet

- Norman Holland Willing Suspension of DisbeliefDocument12 pagesNorman Holland Willing Suspension of DisbeliefemysamehNo ratings yet

- Using Narrative Distance To Invite Transformative Learning ExperiencesDocument18 pagesUsing Narrative Distance To Invite Transformative Learning ExperiencesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Advances in Language and Literary Studies: Article InfoDocument5 pagesAdvances in Language and Literary Studies: Article Infosave tony stark from spaceNo ratings yet

- Revision Exercises Relative ClausesDocument3 pagesRevision Exercises Relative ClausesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Question Tags - Test: A - Which Sentences Are Correct?Document3 pagesQuestion Tags - Test: A - Which Sentences Are Correct?mimisiraNo ratings yet

- Unit 23 I Wish - If Only PDFDocument11 pagesUnit 23 I Wish - If Only PDFAnais Espinosa MartinezNo ratings yet

- Using Wikis To Develop Writing Performance Among PDFDocument9 pagesUsing Wikis To Develop Writing Performance Among PDFemysamehNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Skills Test Units 1–5 Test B Skills ReviewDocument5 pagesCumulative Skills Test Units 1–5 Test B Skills ReviewemysamehNo ratings yet

- Bringing Poetry in Language Classes Can Make LanguageDocument5 pagesBringing Poetry in Language Classes Can Make LanguageemysamehNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Skills Test Units 1-5 Test ADocument5 pagesCumulative Skills Test Units 1-5 Test AemysamehNo ratings yet

- 41 - YILDIZ - GENCAn Investigation On Strategies of Reading in First and Second LanguagesDocument9 pages41 - YILDIZ - GENCAn Investigation On Strategies of Reading in First and Second LanguagesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Vocabulary & Grammar Test Units 1-5 Test A PDFDocument3 pagesCumulative Vocabulary & Grammar Test Units 1-5 Test A PDFMarija SazoņenkoNo ratings yet

- Enlivening The Classroom Some Activities For Motivating Students inDocument10 pagesEnlivening The Classroom Some Activities For Motivating Students inemysamehNo ratings yet

- The Power of LiteratureDocument12 pagesThe Power of LiteratureDana HuţanuNo ratings yet

- An Investigation On Approaches Used To Teach Literature in The ESL ClassroomDocument7 pagesAn Investigation On Approaches Used To Teach Literature in The ESL ClassroomOthman Najib100% (1)

- ISKCON Desire Tree - Voice Newsletter 06 Sept-07Document5 pagesISKCON Desire Tree - Voice Newsletter 06 Sept-07ISKCON desire treeNo ratings yet

- Sri Ramachandra University Application-09Document5 pagesSri Ramachandra University Application-09Mohammed RaziNo ratings yet

- Job Vacancies - SUZADocument3 pagesJob Vacancies - SUZARashid BumarwaNo ratings yet

- Ipoh International Secondary School Checkpoint Exam PreparationDocument22 pagesIpoh International Secondary School Checkpoint Exam PreparationTharrshiny Selvaraj100% (2)

- Science 10 9.4 The Lens EquationDocument31 pagesScience 10 9.4 The Lens Equationjeane san cel arciagaNo ratings yet

- Residential Comprehensive 2015 Leaflet PDFDocument7 pagesResidential Comprehensive 2015 Leaflet PDFmsatpathy2003No ratings yet

- ISAD - HW 2 Information Gathering Unobtrusive Methods Review QuestionsDocument3 pagesISAD - HW 2 Information Gathering Unobtrusive Methods Review QuestionsKathleen AgustinNo ratings yet

- WhizCard CLF C01 06 09 2022Document111 pagesWhizCard CLF C01 06 09 2022sridhiyaNo ratings yet

- Moving Up Guest Speaker Message EnglishDocument2 pagesMoving Up Guest Speaker Message EnglishClarence CarreonNo ratings yet

- The Australian Curriculum: Science Overview for Years 1-2Document14 pagesThe Australian Curriculum: Science Overview for Years 1-2Josiel Nasc'mentoNo ratings yet

- Mechanical CADD CourseDocument8 pagesMechanical CADD CourseCadd CentreNo ratings yet

- List of Cognitive Biases - WikipediaDocument1 pageList of Cognitive Biases - WikipediaKukuh Napaki MuttaqinNo ratings yet

- Blacklight Dress Rehearsal and Tentative Final PerformanceDocument5 pagesBlacklight Dress Rehearsal and Tentative Final Performanceapi-496802644No ratings yet

- Software Engineering Spiral ModelDocument19 pagesSoftware Engineering Spiral ModelJay ZacariasNo ratings yet

- Mechanisms of Change in PsychoDocument14 pagesMechanisms of Change in PsychoConstanza Toledo DonosoNo ratings yet

- Guide - Developing Assessment Tools, Updated 1 April 2015 Page 1 of 11Document11 pagesGuide - Developing Assessment Tools, Updated 1 April 2015 Page 1 of 11Ericka AngolluanNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH PAPER WRITING (Intro)Document39 pagesRESEARCH PAPER WRITING (Intro)Annie EdralinNo ratings yet

- Databaseplan 1Document3 pagesDatabaseplan 1api-689126137No ratings yet

- Prototype Lesson Plan Using Trimodal Delivery PlatformDocument5 pagesPrototype Lesson Plan Using Trimodal Delivery PlatformJEAN P DE PERALTANo ratings yet

- Avoid the 10 biggest mistakes in process modelingDocument9 pagesAvoid the 10 biggest mistakes in process modelingOrlando Marino Taboada OvejeroNo ratings yet

- HG Las Q1 W3 Hawking RamosDocument4 pagesHG Las Q1 W3 Hawking RamosSecond SubscriberNo ratings yet

- Principles of Management: Cpm/PertDocument19 pagesPrinciples of Management: Cpm/PertPushpjit MalikNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Strategic Human ResourceDocument12 pagesThe Effectiveness of Strategic Human ResourceMohamed HamodaNo ratings yet

- Modal verbs board gameDocument1 pageModal verbs board gameEmmaBordetNo ratings yet

- Association of Dietary Fatty Acids With Coronary RiskDocument17 pagesAssociation of Dietary Fatty Acids With Coronary Riskubiktrash1492No ratings yet

- Passport ProjectDocument5 pagesPassport Projectapi-284301306No ratings yet

- Article Swales Cars-Model PDFDocument2 pagesArticle Swales Cars-Model PDFWilliams D CHNo ratings yet

- Unit 5: Geometry: Bridges in Mathematics Grade 1Document4 pagesUnit 5: Geometry: Bridges in Mathematics Grade 1api-242603187No ratings yet