Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Architecture For Children - DISSERTATION

Uploaded by

jasimmeeranOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Architecture For Children - DISSERTATION

Uploaded by

jasimmeeranCopyright:

Available Formats

1

ABSTRACT

This dissertation discusses the importance to learn on childrens architecture

based on the perception of the children. It focuses on the approach to design and

planning of built environment for young children, early to middle childhood. A

trans-disciplinary approach is introduced integrating the knowledge of

childhood development, architecture and landscape architecture. Therefore,

teaching on childrens architecture begins with the discussion on functioning of

children to the built environment. That is, how sensorial and motoric actions as

well as social activities of children are influenced by the elements of

architecture and landscape. Finally, the effects on childrens functioning are

discussed in terms of designing and planning buildings and landscape for the

children.

This also discusses other interesting features like what kind of interiors children

would like for their personal spaces, illustrated with pictures.

The idea behind doing this topic as dissertation, is to, understand the

psychology of children and to learn their considerations which would help as a

guide for design of child space in the future.

Dissertation also includes The Psychology of Abandoned children, as an

attempt to bring to light for social cause.

2

Contents

ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................... 1

LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. 5

1. DESIGN METHODOLOGY ......................................................................... 6

2. FUNCTIONING OF EARLY AND MIDDLE CHILDHOOD CHILDREN 9

3. CHILDRENS EXPERIENCE OF PLACE AND ARCHITECTURE ........ 11

4. METAPHOR OF THE HOUSE ................................................................... 14

5. DEVELOPMENT OF THREE DIMENSIONAL SPACE PERCEPTION IN

CHILDREN ........................................................................................................ 16

6. AN ENVIRONMENT THAT POSITIVELY IMPACTS YOUNG

CHILDREN. ....................................................................................................... 19

An Environment that Matches Young Children .............................................. 19

7. BRAIN DEVELOPMENT DURING THE EARLY YEARS .................. 20

7.1 WINDOWS OF OPPORTUNITY ......................................................... 21

7.2 VISUAL ENVIRONMENT ................................................................... 21

7.3 AUDITORY ENVIRONMENT ................................................................ 22

7.4 INTEGRATED ENVIRONMENT ........................................................... 22

7.5 EMOTIONAL ENVIRONMENT ............................................................. 23

7.6 INDEPENDENT LEARNERS .................................................................. 23

8. INFLUENCE OF ENVIRONMENT ON CHILDREN'S BEHAVIOURS . 24

9. CHILD-SPACE RELATIONS ..................................................................... 24

9.1 From architectural point of view ............................................................... 25

9.2 SPACE IN THE FUNCTION OF PSYCHOLOGICAL STABILITY OF A

CHILD ............................................................................................................. 27

10. DISCOVERING WHAT KIDS LIKE. ..................................................... 29

10.1 Bedroom ................................................................................................... 29

10.2 Toddler Territory ..................................................................................... 30

10.3 Choosing Colour ...................................................................................... 30

10.4 Grand School Districts ............................................................................. 31

3

10.5 The Right Mix Of Lighting. ..................................................................... 31

10.6 Pre Teens Preference ............................................................................... 32

10.7 Powering Up ............................................................................................ 32

11. EXPERIENCING DESIGN: IMPACT OF DESIGN ON CHILD

DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................................... 32

11.1 Importance of size and flexibility ............................................................ 32

11.2 Importance of inside-outside connections ............................................... 33

11.3 Importance of safety and supervision ...................................................... 33

12. IMPACT OF SPATIAL QUALITY:

SPACE, LIGHT, COLOUR, NOISE AND MATERIALS ................................ 34

13. INTERIOR DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS ............................................. 34

14. 14. ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS ........................ 36

14.1 Natural and Artificial Light ..................................................................... 37

14.1.1 Natural ............................................................................................... 37

14.1.2 Artificial ............................................................................................. 37

14.2 Window Coverings .................................................................................. 38

14.3 Hardware .................................................................................................. 38

14.4 Doors ........................................................................................................ 39

14.5 Finishes .................................................................................................... 39

14.5.1 Floor - General ................................................................................... 39

14.5.2 Carpets ............................................................................................... 40

14.5.3 Walls .................................................................................................. 41

14.5.4 Paint ................................................................................................... 41

14.6 CABINETS - GENERAL ........................................................................ 41

14.7 SAFETY AND SECURITY .................................................................... 42

14.8 FURNISHINGS ....................................................................................... 44

15. LANDSCAPE CONSIDERATIONS ........................................................ 45

16. EXTERIOR DESIGN AND PLAY ELEMENTS ....................................... 46

16.1 ACTIVE PLAY ....................................................................................... 46

16.2 PHYSICAL PLAY AREA ...................................................................... 47

4

16.3 SOCIAL PLAY AREA ............................................................................ 47

16.4 QUIET PLAY .......................................................................................... 48

16.5 NATURE PLAY ...................................................................................... 48

17. CONCLUSION ......................................................................................... 48

18. PSYCHOLOGY OF ABANDONED CHILDREN: ................................. 50

18.1 ABSTRACT ............................................................................................. 50

18.2 ABANDONED CHILD SYNDROME ................................................... 50

18.3 CAUSES .................................................................................................. 51

18.4 SYMPTOMS ........................................................................................... 51

18.5 CHILDREN DEPRIVED OF PARENTAL CARE ................................ 52

18.6 UNDERSTANDING THE PAIN OF ABANDONMENT .................... 53

18.7 PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF ABANDONMENT ON CHILDREN

............................................................................................................................. 54

Low Self-Esteem .......................................................................................... 54

Anxiety .......................................................................................................... 54

Attachment .................................................................................................... 55

Insecurity ...................................................................................................... 55

End ................................................................................................................ 55

APPENDIX 1: ENVISIONING OUR FUTURE ENVIRONMENT AND CHILDREN .. 56

APPENDIX 2 : SCHEMES AND PROGRAMMES ON CHILD PROTECTION .......... 58

REFERENCES .................................................................................................... 60

5

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Realms of childrens environmental experience.12

Figure 2: Interactive and explorative Montessori garden...14

Figure 3and 4: Space and equipment suitable for needs of a child

in certain age and architectural and ambiance values.26

Figure 5 and 6: Wavy wall line and new structures on it as dividing

element in spaces for children and simultaneously a gathering place.....27

Figure 7 and 8: Architectural expression finding place in the

child's mind and making emotional attachment..28

Figure 9: Simple bedroom with storage, study space, corner bed

and floor space29

Figure 10 and 11: Modern Toddler Room design.36

Figure 12: Psychology of abandoned child50

6

1. DESIGN METHODOLOGY

Architectural planning and designing spaces for young children is generally

based on adults perception that may not relevant to the childrens functioning.

Form, shape, colour and function are the parameters applied in designing and

articulating the spaces inside and outside the architecture. The design approach

is somewhat not consistent with the literature on childrens functioning in

indoor and outdoor spaces, which suggests that the value of a place is

determined by its function rather than form and colour. In other words, adults

perceive space more on form, function and aesthetic whereas children see the

space more on its functions rather than aesthetic. As such, architects perceive a

pediatric ward of a hospital as a space that accommodates beds, aisle for

movement, toilets and bathrooms, a nurse station, a doctor room and a dressing

room. For play, a playroom is attached to the ward which housed toys and

television and a floor for rest. Studies in pediatric nursing suggest that such

setting leads to boredom, anxiety, and stress to hospitalized children. Among

the reasons that lead children to behave regressively are the healthcare setting

are: (i) strange place to stay, (ii) no sense of control, and (iii) little choice and

lack of things to manipulate. That is, hospital indoor environment limits

children to practice different motoric and sensorial activities. Thus studies in

landscape architecture suggest incorporating garden with the ward for children

to be away from the stress. Moreover, buildings designed by architectural

students are final, that is, leaving little room for children to change or

manipulate the architecture. According to the theory of childhood cognitive

development and literature on childrens perceptual psychology, such

architecture may not generate sense of place attachment. Consequently, the

children could not develop sense of favourite place to the architecture. As a

result children feel bore to go to school or feel fear to stay in hospital. In other

words, the architecture fails to stimulate the childrens cognitive functioning,

affords insufficient space for physical functioning on the childrens terms, and

7

allows little opportunities for the children to socialize in their own choice and

control. The domination of adults on design and planning of childrens space

can be seen in kindergarten. The practice most likely confines the young

children inside the building and occasionally allows the children to engage with

outdoor space such as garden and lawn area. In the indoor, the children may

experience with a variety of furniture and plastic toys in a controlled micro-

climate where temperature, lighting and humidity are similar throughout the

duration of they stay in the building. In other words, much of the childrens

cognitive development is the result of routine experience in a confined space.

Eventually, the children understand the architecture is an element that affords

little changes.

On the other hand, the outdoor space is spacious and open towards the

surrounding that affords the children to move more freely than inside the

building. It is a space that their senses are readily stimulated by greenery and

animals. Its microclimate is natural and dynamic; changes in temperature and

wind and the presence of rain or snow. Such environment affords the children to

understanding the facts that nature is not man-made, it is dynamic and timeless.

In as much, outdoor experience allows the children to interpret and extrapolate

the differences of features and phenomena from the indoor experience.

Cognitively, therefore, the children will deduce that the architecture developed

by adults without their participation as two parts: building and outdoor space.

They can clearly understand the architecture is man-made and the landscape is

natural. In short, they perceive that architecture is not integrated with the

landscape.

In summary, even though we know that experience of childhood in built and

natural environments are diverse, but are often characterized by adult control,

restriction and helplessness. And, the design of spaces for children follows the

8

standard requirement by the design authority or institutional agency. Such

practices did not allow the views of children to be part of the design process of

the architecture. Therefore, children participation in the design and planning of

their built environment is ignored. In other words, children have little voice in

the environment that shapes them and they are expected to obey the rules as

defined by adults. It also means that they has little sense of control and less

opportunity to loco mote themselves freely in space in the built environment

designed solely by adults. Inasmuch, the environment limits them to assume

different body postures, to create their own boundaries and to manifest power

and fulfil their potentials.

This paper presents a review of literature on the importance of teaching

architecture in designing childrens environment by trans-disciplinary approach

that is, integrating the knowledge of childhood development, architecture and

landscape architecture. The discussion focuses on designing architecture and its

outdoor space for the learning and growth development of early and middle

childhood children. It emphasizes the importance to teach the theory of

childrens cognitive developmenthow children perceive spatial and attributes

of place as well its meaningin designing and planning architecture and its

landscape.

9

2. FUNCTIONING OF EARLY AND MIDDLE CHILDHOOD

CHILDREN

In the perspective of child development, posit that early childhood is a period of

incredible fantasy, wonder, and play. They learnt the world as a forum for

imagination and drama that is they reinvent the world, try on new roles, and

struggle to play their parts in harmony. Through sensorial and motoric activities

with peers and adults the children rapidly develop their language and

communication skills. Their physical movement is much influenced by the

functions of the features that they get in contact including furniture and toys in

the indoors and plants and animals in the outdoors.

Their responses to the environments are immediate and inseparable from the

sources of stimulation around them .For example, an empirical study found

that hospitalized children recognized the unfamiliar conditions of their ward,

thus they reacted regressively. Consequently, when they played in the wards

garden, they much aware to the presence of animals such as birds and insects

suggesting their cognitive functioning has improved.

In middle childhood, children are genetically programmed for exploration of the

world and bonding with nature. That is, they learnt on how the world works in

evocative way, their logical reasoning only about concrete objects that are

readily observed. As such the children are active in grasping and understanding

the natural world through play. The play stimulates their cognitive faculties of

sight, touch, taste, audio and olfactory. The children are emotionally affected to

outdoor settings through direct, literal, or tactile contacts. The cognition enables

the children to be active constructors of their own knowledge, leading them to

discover certain logical truths about objects and concepts of the environment.

Therefore, active experience with the environment affords the children to form

logical thought and able to draw logical inferences from the facts that they are

given. Direct contacts with the features and factors of the environment permit

10

the children to explore, imagine and discover. The experience involves the

process of developing and refining fundamental movement skills in a wide

variety of stability, locomotors and manipulative movements.

Therefore, the design of children spaces must conform to their physical,

cognitive and social functioning and development. Physical functioning is the

motoric actions such as fluid rolling, jumping, tumbling, running, and skipping.

Physical development is the patterns of bodily growth and maturation of

children interacting with the surroundings, indoor and outdoor spaces and their

features. Cognitive functioning is the perceptual responses of the children with

the spaces and features. Visual, audio and tactile perceptions contribute much

on the development of the childrens cognitive development. The cognitive

development examines the systematic changes in childrens reasoning,

concepts, memory, and language. Social functioning is the transaction of

children with peers and adults that affords them to assimilate and accommodate

the actions of others. And, social development explores the changes in

childrens feelings, ways of coping and relationships with peers. It is clear that

the functioning and development of the children are shaped by the children

interaction and transaction in the physical features and people. Inasmuch,

children shape their environment and the environment shaped them.

Understanding of these knowledge enable architects and landscape architects to

design and plan a setting, building and landscape, that affords to harness the

three functioning, physical, cognitive and social.

11

3. CHILDRENS EXPERIENCE OF PLACE AND ARCHITECTURE

Children physical movement, cognitive scanning and social transaction in a

space directly influenced by the spatial and properties of the environment.

These interactions involve complex sensorial and motoric actions. Perceptual

responses (sight, tactile, audio, smell and taste) and mobility in an environment

reveal a lot of significant information. In other words, perception is an active

experience, in which a child finds information through mobility. We must

perceive to be able to move around, and we must move around to be able to

perceive. This is an ecological perceptual psychology framework which

recognized by a few environmental psychologists. Since children contact with

architecture involves perception and movement, it is appropriate to teach

architecture using this framework. Therefore, studio project on childrens

architecture should begin with the introduction of how children perceive the

spatial and properties of the environment.

To give an example, found that architectural projects involving childrens

participation facilitate architects to create innovative design in accord with the

childrens perception and affection to space and building.

Notwithstanding, the architecture and its landscape should be designed both to

support function and to nourish the childs sensory and aesthetic sensibilities.

For example, a hospital ward functions as a place to recover health and its

garden for play and rest.

A built environment that affords a child to be cognitively alert to the external

stimuli through movement and social actions will encourage him or her to

affiliate or create bonding with it. According to Moore and Young, the bonding

is called as inner space (Figure1) created by children through three types of

sensual experiences: cognitive, affective and evaluative. Cognitive experience is

12

the formation of thinking and problem-solving skills; affective experience is the

emerging of emotional and feeling capacities; and evaluative experience is the

creation of values, belief and perspectives to the environment. For example,

after experiencing more than two days in a hospital garden, ill children

established sense of attachment to the garden that is intending to come back to

the hospital if they get ill again.

Figure 1: Realms of childrens environmental experience

Referring to Figure 1, an architecture and its landscape is understood by

children as physiographic space affording a child to show his physical strength

and dexterity to make contacts, both perceptual and physical, with the elements

and climatic forces of the place, either routinely or occasionally. In other words,

the space is where childrens senses are stimulated through sensual and motoric

activities. Old posits that movement in play such as in playroom stimulates a

child senses in a rhythmic patterns of predictable sameness. However, the

playroom should also allow gradual change or moderate diversity that would

trigger fascination and satisfaction. In childhood psychology, the phenomenon

is known as difference-within-sameness that affords a child to develop a mental

construct that the architecture is a structure, and structure develops. Such

development occurs frequently in the natural world. For example, in a forest

setting, Fjorfort discovered that middle childhood Finnish children recognise the

13

forest as a place affording them functional and construction plays, and these

plays improved their motor abilities. And, in hospital setting, 2006 found that

hospitalized children increased their locomotion and dexterity in experiencing

hospital garden. Moreover, childrens physical participation with the

architectural features and natural landscape elements extend to satisfaction and

the experience stay in their memory. And, memory is a derivative of place

attachment. Positive emotions to a place of play permit a multitude of affective

opportunities for engagement, discovery, creativity, revelation, and adventure

surprise. In turn, the affection allows the children to evaluate the place with

values. Therefore, experiencing the environment is an essential, critical and

irreplaceable dimension in the growth and functioning of children. The

empirical studies implicate that kindergarten or hospital ward should be

integrated with the outdoor spaces especially greenery. The architecture not

only a milieu for learning or health recovery but also a physical setting that

triggers the positive behavioural responses such as place attachment and place

identity.

Figure 2 illustrates a design of a kindergarten by an undergraduate student. The

design begins with rigorously understanding of childhood cognitive

development. And, the design views the building and outdoor landscape as

holistic entity to for young children to learn and grow. The design anticipates

the children are attached to a place. Place attachment is when they show

happiness at being in it and regret or distress at leaving it, and they value it not

only for satisfaction of physical needs but for its intrinsic qualities. It will not

surprise to find children longing to come back to school after leaving for home

or going back to hospital after being discharged.

14

Finally the architecture and its landscape is also a social space where children

play with peers or adults and create friendship, acquaintanceship, reduced social

regressions and reduced social withdrawals. These are progressive responses of

childrens social development. This is because during social play children

expand their cognition of the place by assimilating the actions of others

particularly peer. Assimilation is a process of dealing with a feature or event

consistent with an existing schema. Overtime, through repetitive encounter,

children accommodate their actions creating a new schema which is an

expansion from the previous one. Thus, interaction in a social space such as

communication and turn taking offers more stimulations and feedbacks to the

children. Therefore, the childrens cognitive faculties including schema to the

place is expanded.

4. METAPHOR OF THE HOUSE

Any contemporary discussion of Architecture must coalesce, not only the

perceptual systems that produce buildings, but the human emotions connected

to our body image and the buildings we know as home. The house can be said

to be an extension of our bodies. Being vertical, the house rises upward like the

human body from the cellar to the attic. The attic provides a roof that gives

shelter from the rain, snow or sun. The cellar is said to contain our deepest

15

fears. The concept of the house is considered to be much more than a building

that can be described by its appearance or simply as a space that is-inhabited.

All of the houses that we have lived in hold memories for us and bring forth

images that shape themselves in a continuous life long process. Our memories

of houses can provide us with the inner feelings of protection and intimacy that

provide a sense of stability.

The entrance of a house holds an important meaning since it is the boundary

that separates our private life from our public life in the community. The front

or facade of the house can be compared to the front of our bodies standing

symmetrically facing the world. Windows can permit a view in, out or shut out

the community. The backs of homes, not always symmetrical, exhibit the

private life of people. Boundaries are usually defined in backyards in order to

discourage interference from the outside. The interior of the house complements

the exterior with a vertical directionality moving up and down by means of

stairways. Stairs leading up may direct us to rooms that provide us with privacy

or separateness, while concealed stairs leading down to the basement may

exemplify the idea of a cave. Rooms within a house can either be those that are

utilized for group activities or those that provide individuals with seclusion.3

In order to further develop the incorporation of awareness of body image in

architectural design, research done in the area of proxemics can be

helpful. Proxemics studies the cultural influences of how we experience space.

As people throughout the world have developed their cultures uniquely and

distinctly from one another problems can and do arise when cultural groups

attempt to communicate with one another. For the purposes of this paper human

space perception is emphasized, while it needs to be remembered that we

interact with all of our perceptual systems. Research shows that people oriental

themselves in space according to the culture that they were reared in. Each of us

sense other people as close or distant. Four distance zones affect how we react:

16

intimate distance, personal distance, social distance and public distance. These

distance zones greatly affect how people use their senses to distinguish between

the relationships of others, their feelings and what activity they are involved in.

What may be considered intimate in one culture might be public or personal in

another culture. Without going into detail describing the distance zones, the

awareness of these territorial spaces is particularly valuable when designing

urban environments. Crowding human beings into vertical buildings without

considering the negative effects of crowding upon the human needs within

different relationships is harmful. The result becomes evident when we observe

the stress found in many urban dwellers. Contemporary Americans have need

for urban environments that provide a variety of spatial experiences.

5. DEVELOPMENT OF THREE DIMENSIONAL SPACE

PERCEPTION IN CHILDREN

The study of space perception can be defined as the process by which we

acquire knowledge through the senses of the position of objects and their

relations in space to each other, their general surroundings and the perceiver.

Though this is a complex process; occurs in children gradually from birth. The

developmental growth in space perception for the child initiates with what is

known as Mouth Space. Mouth Space occurs during the first three or four

months of the infants life and is connected to sucking. During this time infants

look at objects that emit sounds, and appear to realize that they belong

together. Tactile Space is developed through the infant touching his or her own

body. In Visual Space the infant follows moving objects with its eyes. At about

four months the infant will look at an object held in front of him/her and reach

and grasp for it. The visual and the tactile impressions begin to combine at this

age towards an understanding of what shape is. Gradually the infant begins to

learn that the same object may appear differently when it is seen from a variety

of views at different distances. Throughout this process the infant sees that the

17

shape he/she is looking at visually corresponds to the shape that he/she feels

with his/her hands. The infant is approximately two before he/she begins to

understand that objects have their own identity even when they are moved in

space. Young children begin to name concepts of space such as in, out, above

and below when they are about three. Yet, the objects are not yet perceived, as

wholes since the child is experiencing the object(s) haptically. This can be

interpreted to mean that the very young child remains almost passive when he

has to identify objects from touch. The childs grasping and handling is rather

haphazard.

Between the ages of 4 through 7 the tactile experiences with an object can be

translated visually. This happens when the child attempts to draw from tactile

perceptions. The childs drawing will reflect his/her ability to explore objects

and recognize shapes from tactile experience. Initially rounded shapes are

drawn followed by those shapes drawn with straight lines. One must be aware

that this process develops quite slowly in the child. In addition children can

match shapes more easily than they can draw them.

By the ages of 8 and 9 the child becomes aware of the bodys orientation to the

horizontal and vertical coordinates of space. Objects such as buildings and trees

can be perceived as upright forms as well as our bodies, due to the pull of

gravity. Our ears contain the mechanisms that indicate when our head is not

parallel to gravitational pull. It appears that the more active motor experience

the child has the greater awareness he/she has of the horizontal and vertical

condition of the environment. Active participation in such activities as walking,

bicycling and other sports can develop this skill when contrasted with passive

movement such as bus riding. The child is moving through a world that contains

objects scaled generally for adults. This observation suggests that playgrounds

need to be designed with the childs sense of scale; a scale that provides spatial

18

learning activities between the levels of toy playing and the larger adult scaled

environment.

As the child of 8 to 9 is becoming more aware of depth and distance in space,

he/she is also developing perceptions of body image, as attitudes towards their

bodies and the bodies of other people. Research in the area of how children

perceive the size of their bodies appears to show that children will overestimate

or underestimate the size of their bodies in relation to what is culturally

desirable. Many variables influence how the child perceives his/her body: sex

differences, personality types, and emotional feelings of self-importance,

success and power. Generally, the child, as well as the adult, functions within

three dimensional boundaries that surround our bodies. For the child these

boundaries are not fixed since their growth processes are not complete.

8

Children develop their awareness of distance and depth very slowly. Judgment

of distance becomes clearer as the child has more experience with actually

traversing the distance themselves. The child will gradually perceive the

changes in; the appearances or objects as they move towards them or away from

them. Older children through maturation, experience and training can usually

perceive that objects gradually recede into the distance. The focusing of both

eyes in what is known as binocular vision is necessary for accuracy in depth

perception. Changes in the size of objects will cause them to appear smaller as

they recede into the background. The texture of the surfaces of objects becomes

denser the further they are away from the viewer. As the older child becomes

less self-cantered and more aware of other viewpoints, what is known as linear

perspective (parallel lines converging to a vanishing point at the horizon) can be

understood. The horizon is relative to ones point of view and the surrounding

environment (urban, flat rural land, ocean, hills, mountains, etc.). Generally we

look up towards objects that are distant, and down at near objects. Movement

and the speed at which an object moves convey depth. Objects which are closer

19

appear to move more and faster than similar objects at greater distances.

Shadows created as a result of a light source contribute to the impression of an

object being in three dimensional spaces.

In any discussion of developmental growth in children it must be remembered

that there are a multitude of variables affecting the learning process. The

perception of spatial relationships is a complex learning process that does not

complete itself in childhood; nor can it be isolated from other learning

processes. It is discussed here for the purpose of guiding one in planning art

activities that can improve the childs awareness of space. This awareness of

space is connected directly to our thoughts, feelings and imagination as we

experience buildings in our environment.

6. AN ENVIRONMENT THAT POSITIVELY IMPACTS YOUNG

CHILDREN.

An Environment that Matches Young Children

The first step in creating an appropriate environment for infants, toddlers, and

preschool children is to examine how young children learn and develop. Each

stage of development has unique characteristics that influence how a child will

experience his or her environment.

For example, infants and toddlers learn about their world by acting on objects

and materials in their environment. As the toddler feels the texture of a beach

ball, pushes the air filled object, and rolls it across the carpeted floor, he

constructs an understanding of the ball. Because infants and toddlers learn by

interacting with the environment, their space must be designed with many

opportunities for physically exploring real materials. Varied materials are stored

where the child can easily select them. Other items are placed where they are

not visible but can be retrieved when a specific activity or individual need

20

occurs. Pre-schoolers are active learners who continue to examine materials

while beginning to use objects in more complex combinations. They are

developing symbolic representation as they take on roles and participate in

socio-dramatic play. Their language explodes during this period as they try to

find "labels" for the objects and people in their world. Language gives young

children the power to question and find answers. Learning centres are effective

ways to organize and support these developing abilities. The center areas clearly

communicate to pre-schoolers what activity occurs in this area and the available

materials that will stimulate their play. Traditional centers as well as unique

centers encourage language interactions, socio-dramatic play, and the

construction of experiences based on their level of understanding. By adding

literacy materials including books, paper and writing tools, this construction

will include "reading and writing" opportunities.

7. BRAIN DEVELOPMENT DURING THE EARLY YEARS

Early childhood educators and neurologists agree that the first eight years are a

critical time of brain development. Infants come into the world with a brain

waiting to be woven into the complex fabric of the mind. Some neurons in the

brain are wired before birth, but many are waiting to be programmed by early

experiences. The early environment where young children live will help

determine the direction of their brain development. Children who have severely

limited opportunities for appropriate experiences will be delayed; this may

permanently affect their learning. But, children who have the opportunity to

develop in an organized and appropriate environment are challenged to think

and use materials in new ways.

21

7.1 WINDOWS OF OPPORTUNITY

New brain research indicates that there are important "windows of opportunity"

that exist during the early years. These are considered the "prime" times for

these areas to be developed. Experts have identified several areas that are

particularly critical during the early years these include: language, logical

thinking, music, vision, and emotion. Appropriate and interesting experiences,

during the early years, in these specific areas can have a positive impact on the

child's current development as well brain connections that will last a lifetime.

7.2 VISUAL ENVIRONMENT

During the first eight years, children are developing their visual acuity. Their

perceptions of objects, movement, and print are expanded as they have

opportunities for experiencing interesting visual images. Changes and variations

of design intrigue children and cause them to visually attend to the unusual. The

young child's environment that includes interesting visual aspects draws them to

examine a painting on the wall or recognize a drawing that they have

completed. Displays and panels provide visually interesting content to examine

as children move about in the classroom space. In the past, many early

childhood classrooms were so filled with commercial decorations, materials

and, "stuff" that young children were visually overwhelmed. Today, we are

working to have less clutter and a more organized display of materials and

work, so young children can visually attend to and enjoy the important features

of the environment.

22

7.3 AUDITORY ENVIRONMENT

Music and sound patterns stimulate several portions of the young child's brain.

A variety of music and instruments can expand the sound world of young

children, while developing musical enjoyment. Singing in circle time and during

transitions encourages the children to discriminate sounds and identify familiar

patterns. Making music with simple rhythm instruments provides opportunities

for children to connect the object with the sound that it produces and to control

the production. Recordings of vocals, instrumentals, and folk instruments

provide another listening experience that expands the auditory environment for

young children. Providing a special area for group participation, as well as a

center where sounds can be explored individually, can add to the auditory

possibilities of the classroom.

7.4 INTEGRATED ENVIRONMENT

Young children make many connections when they participate in meaningful

activities. Integrated activities that connect several types of learning are

particularly effective for preschool children. These experiences provide

stimulation for several portions of the brain and make additional connections

that extend learning. Some of the experiences that are particularly powerful for

integrated learning and building connections are learning centers, thematic

episodes, and projects. To support integrated learning, materials must be readily

accessible to the play areas and stored so that they can be selected and included

in the play. To encourage the continuation of projects, there must be places to

carefully store objects while the work is in progress.

23

7.5 EMOTIONAL ENVIRONMENT

It has been suggested that the emotions of children are strongly influenced by

the responsiveness of the caregiver during the first years of life. If the child's joy

is reflected by the caregiver and the emotion is reciprocated, the child's security

is strengthened. If the child's emotion is interpreted as annoying by the

caregiver, the circuits become confused. A caring and responsive caregiver

provides a positive climate for young children that will impact not only

emotional security but also many aspects of cognitive development. Children

who feel secure and supported will experiment, try new things, and express their

ideas. The appropriate emotional environment also respects young children,

while understanding individual differences. This means that each child has a

place to collect "valuable" thingstheir pictures andwork are displayed in the

classroom. There is a place where the child can retreat when things get too busy,

or when he becomes tired.

7.6 INDEPENDENT LEARNERS

An independent learner is able to make personal choices and carry out an

appropriate plan of action. Beginning in infancy and toddlerhood and

continuing throughout childhood, there is the growing need to become an

independent person. Children want to do things for themselves and in their own

way. Pre-schoolers become increasingly competent in making choices, creating

a plan, and following through with a project or experience. If children's ideas

are valued and their interest followed they will work on projects for long

periods of time. This process is supported in an environment where children are

able to revisit and reflect on their plans, while using their knowledge in ways

that are meaningful for them.

24

An effective environment is designed so even the youngest of children can

become independent. There are many opportunities for them to be successful as

they work to do things for themselves. They are not dependent on the teacher

and constantly asking for every material they need. An orderly display of

accessible materials grouped together will help children understand that they are

capable of making decisions. The environment will communicate to them, "you

can make the selection, you have good ideas, and you can carry out the plan for

yourself."

8. INFLUENCE OF ENVIRONMENT ON CHILDREN'S BEHAVIOURS

The environment in which young children live tells them how to act and

respond. A large open space in the center of the classroom clearly invites young

children to run across the area. If few materials are available to use, children

will create interesting happenings, including conflict. If the procedures for using

learning centers are not predictable and easily understood, the children will

wander in and out of the areas with little involvement in play. The arrangement

and materials in the environment will determine the areas where children focus

their work. It will also influence the number of conflicts that occur or the way

the group works together. If the materials are hard plastic, the children are

invited to be rough with the objects with little concern for their treatment. If a

beautiful flower arrangement is on the table, they will learn to visually examine

the flowers and gently handle the delicate blooms. Children learn to be

respectful of their environment if they have opportunities to care for beautiful

objects and materials.

9. CHILD-SPACE RELATIONS

There are various concepts of the child-space relation. A widely accepted

concept is the "awareness of the place", which characterizes a larger scope and

25

higher synthetic level because it includes other concepts describing human

relationship towards the space. The most cited concepts of this type are:

Binding to a place in space

Identification and

Belonging to a place

Trying to define a place that a child is attached to, it is often said that it is the

space in which a child is happy, and regrets leaving it and feels dissatisfied

when it has to go. However, the real reason for a child's bonding to a certain

place in space is that such place has some special attributes.

9.1 From architectural point of view, a certain space and its arrangement as

the structures with physical characteristics and measurable material attributes

are primarily suitable for physical needs of children. However, it is just one

aspect of child-space relation. The next and higher level of this relation is the

child's feeling of attachment to a certain architectural unit in space, as a

psychological connotation. Thus, the certain ambiance in which a child dwells

with its architectural attributes is not only an answer to child's physical needs

but has some essential qualities, primarily for psycho-social development

(fig. 3). Regarding those facts, it is considered that during latent years of mid

childhood the strong connection with family base gradually weakens and

decreases in the child's experience, and a physical surrounding becomes more

significant through bonding to those places that are architecturally designed in a

certain way.

26

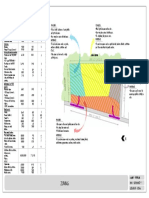

Fig. 3 and 4 Space and equipment suitable for needs of a child in certain age

and architectural and ambiance values (Kindergarten "Nido Stelia" in Modena

Italy, 2004.)

When talking about the concept of identification with some place in space, it is

considered that kind of identification represents a "factor in the substructure of

personal identity, which in a larger context consists also from the knowledge of

physical world in which the person lives. Such knowledge consists of

memories, ideas, attitudes, values, preferences, meanings and concepts of

behaviours and experiences which refer to the wide complex of physical

environment and defines, day in day out, existence of every human being". In

the essence of such relation with physical environment is the knowledge of

some architectural space (Fig. 4) in the form of the person's past, experienced in

a certain environment and ambiance. In that way, the past of the person

becomes the part of some place, and architectural space with what constitutes it

and what is set inside of it and makes it an architectural unit, becomes an

instrument that fulfils biological, social and cultural needs of the person using it.

27

9.2 SPACE IN THE FUNCTION OF PSYCHOLOGICAL STABILITY

OF A CHILD

Fig. 5 and 6 Wavy wall line and new structures on it as dividing element in

spaces for children and simultaneously a gathering place (The basis of ground

and upper level of kindergarten "The Little School", San Francisco, Mark

Horton, 2005.)

The most of knowledge about identification with certain environment suggests

that dwelling in the environment that children attach pleasant feelings to, causes

reduction of anxiety and helps them in daily social relations when certain

psychological "stresses" should be sustained and when a child needs a help in

self-preservation. Thus, a degree of attachment to certain architectural

environment and feelings that a child may develop for it, suggest that those

factors contribute in development of key aspects of persons identity, especially

regarding self-respect and self-pity. This model of person's identity holds

potential for understanding of phenomenon that formation of a personal identity

of a child is also achieved through development of certain feelings for some

architectural ambiances and building specific relations with them.

28

Fig. 7 and 8 Architectural expression finding place in the child's mind and

making emotional attachment (The ground level layout and characteristic look

of kindergarten in Caesarea in Israel, T.Klimor and D.Knafo, 2006.)

The concept of phenomenon of a belonging feeling to a certain environment is

related to certain advantages of an architectural ambiance and potential to

achieve certain aims of behaviour. That concept gives an answer to the question

why a given specific environment is more suitable for something that someone

likes doing than the others. This principle is defined as a possibility of

belonging to a certain place in space and arises as a result of the way the quality

of relationship to a certain place is experienced. The belonging to a space is

different from attachment to a certain environment in two ways: May have a

negative connotation when a given space limits achieving a value as a result and

Strong impression of experiences in a certain environment can be less based

upon fulfilment of specific goals of behaviour than on feelings. Attachment to a

certain architectural space, identification with it, and possibility of regulating

privacy and recovering of environment results in appearance of favourite place

phenomenon. A place with such attributes has the role of regulating the relation

between personal and emotional in a person, after some sudden and conflict

situation. It is the place that allows an individual to amortize the negative and to

reactivate positive emotions. Sometimes there occurs an anthropomorphic

phenomenon when the favourite space is given a nickname. Thus, positive

29

forms of relation to a certain place in the favourable space fulfil emotional

needs of a child and help in developing and maintaining identity.

10. DISCOVERING WHAT KIDS LIKE.

10.1 Bedroom

The best kids bedrooms are shaped around functions like sleep, play, be with

friends or spend solo time and around the kids themselves their ages, interests,

personalities, and imaginations.

The younger the child, the more simple the room should be. A toddler is happy

with a few open toy bins at floor level, while most preteens need ample shelving

and drawer space. A small childs room should have zones readied for crafts,

games, and reading, as well as generous floor space for active play. Older

children dont need such compartmentalized areas, but their rooms should still

have at least three zones: for homework, for sitting with friends, and for

sleeping.

Every child welcomes a place to relax or decompress. Reserve the quietest,

cosiest corner for the retreat, then structure the rest of the room around it.

Platforms, two-sided cabinetry, and archways help define different zones, while

lofts, nooks, pass-through and secret hide-away add intrigue.

Fig 9 . Simple bedroom with

storage, study space, corner

bed and floor space

30

10.2 Toddler Territory

Whether rollicking on the floor, rolling a toy truck, or rapt in a storybook,

toddlers are keenly engaged in every experience. A toddlers room should not

only be a cheerful, enabling environment, but it should also be part of the

adventure. Stow toys where they are easy for toddlers to see and reach, using a

dynamic mix of colourful shelves and open bins. Add a storage/play structure

shaped like a car, horse or train or something.

Cover low walls with chalkboard or magnetic paint. Cluster colouring books,

puzzles, and skill-building games alongside a kid-size table and seats.

Reserve plenty of open floor space. Toddlers need room to run around, play

with big toys, or stretch out on the rug. Just as important: a soft-surfaced,

enveloping corner where kids can curl up and rest.

10.3 Choosing Colour

What colours are best for a childs room? The answer depends partly on the

room and partly on the childs nature.

Light colours expand space and darks lend intimacy. Cool colours such as blues

and greens are soothing, while warm reds, oranges and yellows are stimulating.

By age three or four, children have favourite colours. Use these colours to give

their rooms a personal flavour. To find a winning palette, let the child to choose

their favourite from primary and secondary colours. Next, ask for a second and

third choice. Sort through and refine the choices but a variety of selections.

The least intense shade probably is best as the dominant room colour. Use

another favourite colour for a third of the rooms finishes, such as on molding

31

or cabinetry. Top off the scheme with accents in the third tone. Ensure the

colours stay true and appealing throughout the day and under different lighting.

10.4 Grand School Districts

Life is big and bold for grade school children. They are making new friends,

discovering new interests and activities, embracing the latest fads, and

delighting in make-believe. Thats why bold ideas are just right for school

childs bedroom. Go ahead with the vibrant colours, canopy beds etc. Kids this

age love surroundings drenched with atmosphere.

They also invest energy and enthusiasm in the sports and hobbies theyve

developed an interest in. Set up part of the room as a dedicated space for sports

equipment, model plane projects, jewellery making etc. Incorporate shelves and

display walls around the room for handiwork, collections, posters, and prizes.

10.5 The Right Mix Of Lighting.

With good lighting, a child room is safer and more pleasant to use. The room

needs both overall ambient lighting and channelled task lighting. Decorative

accent lights are icing on the cake.

Ceiling fixtures should illuminate the whole room, leaving no shadowy corners.

Adjustable track lighting can provide either ambient or task lighting, and they

can be repositioned easily if the room is reorganized.

Nonglare task lighting should evenly illuminate the entire work or play area.

For full coverage, ceiling lights for a desk should be as far behind as the desk

18 in. behind an 18 in. desk, for instance. Reading lights should beam over the

readers shoulder.

32

Do not forget natural light. If windows are skimpy or absent, consider adding a

skylight.

10.6 Pre Teens Preference

Preteens want to express who they are, but they also want to be like their

friends. The result is a room that should make two statements: This is me, and

Im cool. Girls may prefer feminine themes while boys may go extreme themes,

featuring sports, science or outer space. Expansive storage space would be

required. Prominent display around the room defining as a source of

encouragement.

10.7 Powering Up

As kids grow up, so do their electrical needs. They steadily accumulate

electronic equipment, from computers and phones to audio systems, DVD

players, accent lights, hair irons etc. Plan ahead for this surge of power usage by

installing ample wiring and outlets.

11. EXPERIENCING DESIGN: IMPACT OF DESIGN ON CHILD

DEVELOPMENT

Three main elements of the physical environment are viewed as the key

contributors to a quality physical environment: size and flexibility, inside-

outside connections, and safety.

11.1 Importance of size and flexibility

Size is the primary consideration for all, describing how space and a feeling

of space were critical to quality. Concurrently, the flexibility of that space is

seen as an important contributor to quality. Educators describe how large space

33

give children room to work, dilute the noise and make visual supervision easier.

Flexibility means a room could be easily changed to keep up with childrens

imaginations and ensure they were not bored.

11.2 Importance of inside-outside connections

The connections between the inside-outside is extremely important and having

a large and interesting natural outdoor space is critical for childrens learning.

They valued spaces that were light and airy, with large windows and

connections to the outdoors - one centre had a large veranda which was utilised

often and highly valued.

When questioned about how they would spend money to improve childrens

learning outcomes, a common response was to enhance the outdoor experience,

especially providing gardens that would grow food, were colourful and scented,

and incorporated wind chimes and stepping stones for exploration. Educators

also desired more outdoor access, natural spaces and obstacle equiptment (e.g.

Soft fall outside and a play fort). Interestingly, while one educator desired a

natural backyard and grass, she felt that as so many children now have grass

allergies that might be impractical.

11.3 Importance of safety and supervision

Safety and supervision were overarching issues associated with judgements of

quality about the physical environment. At a more abstract level, educators

explained how as this was childrens first time away from their families,

everyone needed to feel happy to leave mum and know that theyll be safe and

theyre capable and theyll enjoy being in this environment. Good design

enabled this transition giving children and parents a feeling of confidence and

enabling educators to focus on teaching, rather than on always monitoring

potential hazards. Educators commented that while safety was predominantly

for the child, the physical environment needed to be safe and usable by the

34

teachers. They emphasised windows between rooms for active and easy

monitoring and the elimination of design hazards, such as stairs and cords, so

the children would feel and be safe in the space.

12. IMPACT OF SPATIAL QUALITY:

SPACE, LIGHT, COLOUR, NOISE AND MATERIALS

Best practice design guidelines for early childhood centres emphasise how

specific elements of spatial quality (space, light, colour, noise and materials)

impact on childrens learning and development. Specifically, the best layout of

a learning environment is modified open-plan facilities, retaining the best of

open and closed plan facilities. Research has explored vertical space (i.e.,

height), found that continuous bland ceilings had a negative impact on a childs

cooperative behaviour whereas differentiated ceiling height have a positive

impact, creating different experiences and social exchange. Lighting should be

selected to suit the activity and the space, providing flexibility in natural and

artificial light to meet various tasks and mood requirements, whilst colour can

create a sense of place, communicate information, create landmarks for spatial

orientation and encourage cooperative behaviour through variation. Exposure to

uncontrollable noise has a negative impact on childrens cognitive development,

reducing memory, language and reading skills.

The sensory world is also a rich source of information, with the materials and

finishes used offering a good source of variety and tactile sensory stimulation.

13. INTERIOR DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

Spaces should be designed to ensure safety, provide clear supervision and

contain a range of program areas that are age appropriate and support

35

development. The space should be designed, finished and furnished to

encourage children to be engaged in a safe and comfortable environment.

The space should include a variety of open spaces along with smaller more

intimate spaces. The space should be designed to be flexible and support a

variety of activities such as quiet and active play, creative play, resting, and

eating. The finishes, colours, layout, furnishings and staff amenities need to be

carefully considered to support these various activities. The design should

encourage children to both explore the room, engage in different activities while

providing the clues and the design elements that allow other activities to occur

simultaneously.

Planning for and providing ample storage for both materials and equipment is

important. Anticipating the areas in which cots will be stored must be

considered. If stored in the playroom, cots are counted as an obstruction and

cannot be included as part of the calculation for capacity. Well designed and

adequate storage contributes to the organization and accessibility to things

needed for each program and group of children. Keeping the space uncluttered

improves the flow of movement from one activity space to another and

minimizes children interrupting the play of others.

Toddler Room Considerations

A toddler room should be designed to encourage and support independence,

while strengthening social skills. Materials and developmentally-appropriate

toys should be easily accessible on open shelves. Child-sized furnishings and

equipment, designated areas with concrete guidance cues (i.e. quiet area,

cognitive area, and book corner) and the flow of the room must also be

considered.

36

Toddlers are busy children, so they need open spaces to move and experiment

with a variety of toys and equipment. Room colour, natural lighting, a space to

move and develop growing muscles, and a variety of textures must be factored

into an inclusive physical environment for toddlers. Areas for small group

activities with multiple toys that promote parallel and social play, will help the

toddler develop decision making skill

14.

Fig 10 and 11 Modern

Toddler Room design

37

14. ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

The following should be considered in the design of a child space.

14.1 Natural and Artificial Light

14.1.1 Natural

Natural light and views are a high priority. Operable windows are preferred

even when building is air conditioned. Window openings should be at a higher

level, out of childrens reach.

Exterior windows promote engagement with the outside world.

Windows that open into corridors or between rooms help children to see

themselves as part of a larger community. They also permit visual surveillance

by staff from adjoining rooms.

Each room must have clear window glass that is the equivalent of 10% of the

floor space to ensure natural light. Light can be shared from one room to the

next by enlarging existing windows or cutting out windows between rooms,

however, it will not be counted in the calculation of direct light.

14.1.2 Artificial

Florescent lighting is the most efficient and cost effective form of artificial

lighting. If they are to be used, it is recommended that bulbs are selected that

provide the most natural colour mix. Fixture covers can lessen the glare of

florescent lighting. Whenever possible florescent lighting should be

supplemented with incandescent or halogen lights and sconces installed on a

separate light switch.

A range of lighting will provide program areas with the light needed for

specific tasks or atmosphere.

38

Dimmer switches should be provided in sleep and/or quiet areas.

Each room should have its own light switch. Windows

Windows shall be provided with a regulator preventing them from opening

more than 100 mm (4 in.) where it is possible for a child to access the window

or for all windows located above the first floor.

Consider making the upper portion of the window a minimum 1000 mm (3)

above the floor.

Select high performance windows and screens to reduce operating costs and to

reduce drafts.

14.2 Window Coverings

Easily cleaned or vacuumed window treatments, such as shades should be

used. Curtains can cause health concerns.

Cords should be eliminated or secured in a manner that it they are kept out of

reach of children.

In sleep areas window coverings should effectively block the light, be

accessible to staff and easy to use.

Use of PVC mini-blinds can be hazardous to the health of children and should

not be used.

14.3 Hardware

Install lever door hardware throughout.

Consider accessibility, i.e. level of hardware etc.

All doors must be operable from the interior without the use of a key.

39

Building code requirements can conflict with program and security

requirements; therefore consider security and exiting issues early in the design

process.

Check with local fire and building departments regarding use of magnetic

locks and electronic hold open devices for doors.

Door closures should be slow-release as they close.

Analyse different keying and access systems. Options include proximity

readers, card system, numeric pads, and keys. Ensure selected system is

compatible with auto door opener and security system.

Install locks on all storage, closet, and cabinet doors.

14.4 Doors

At room entrance dutch doors with glazed top and bottom panels are

recommended.

Provide solid core doors with double glazed vision panels when sound

transmission is a concern. Provided sound seal gasket and impact bumpers to

further reduce noise.41

Sleep Room (if provided) and Play Activity Room doors should be wide

enough to allow easy manoeuvring and evacuation of cribs in case of

emergency. Consider 1000 mm (3 ft 4 in) wide doors.

14.5 Finishes

14.5.1 Floor - General

Consideration should be given to the existing floor temperature in infant and

toddler areas. For example, if the floor is a concrete slab over an unheated space

40

consideration may be given to selecting a floor material or a floor system to

mitigate this problem.

Select floors that are durable, easy to clean, and maintain.

Consider installing sheet flooring material and vinyl tile in various colours and

patterns.

The surfaces of ramps, landings and stair treads shall have a finish that is slip

resistant and have either a colour contrast or a distinctive pattern to demarcate

the leading edge of the stair tread, landing, as well as, the beginning and end of

ramp.

In rooms where: food and/or drink are prepared, stored, or served, and in

washrooms, floors and floor coverings shall be tight, smooth and non-absorbent.

A coved base should be installed.

It is recommended the entry vestibule floors should be non-slip with coved

base.

14.5.2 Carpets

If carpet is desirable, consider carpet tiles.

Choose non-abrasive materials with a non-slip backing.

Care should be taken that carpet edges are bound and flat to avoid tripping.

Secure area rugs to prevent tripping hazards.

In sleeping areas, carpet should be dense and low pile, glue down type for ease

of crib movement.

Conducive to high frequency of clean/washing.

41

14.5.3 Walls

Install abuse-resistant gypsum board.

Install cement board in all wet areas.

Install wall protectors and corner guards on the lower half of the wall in high

use areas.

Consider materials such as vinyl wall covering for durability and ease of

maintenance, Vinyl provides a tackable surface from floor to ceiling.

14.5.4 Paint

Choose high-quality, washable paint.

Carefully consider the various paint sheens available and the appropriateness

for each area and surface.

14.6 CABINETS - GENERAL

Counters to have post-formed, coved back-splash. Counters to be surfaced

with impervious material that is easy to maintain.

Provide solid edging in either vinyl or wood on all cabinet doors and shelves.

It is recommended that all millwork be constructed with durable and easily

cleanable surface such as plastic laminate or melamine (including the interior of

the cabinets).

Provide locks on door and drawers where required.

Use heavy duty 110 degree hinges and full extension drawer slides.

42

14.6.1 SIZE AND DESIGN

Cabinets designed to store equipment or personal belongings intended to be

accessible to children should be low to promote childrens independence.

The design of moveable storage units contributes to program flexibility.

Refer to specific program areas for recommended dimensions.

14.7 SAFETY AND SECURITY

14.7.1 GLAZING

Interior and exterior glazing: provide protective firm, laminated and or

tempered glass in areas that glass could be broken. Laminated glass and safety

film provides a higher level of security than tempered glass. Refer to OBC for

additional requirements.

Interior doors should have a view window 100mm x 610 mm (4 x 25) so

that all spaces in the building can be supervised. Provide interior windows to

improve sight lines.

14.7.2 ATTACHMENT OF EQUIPMENT/MATERIALS

Provide solid blocking in walls. Attach cabinets, book cases, grab bars, hand

rails, guards, etc. through wall board and into blocking or other approved

fastening device.

14.7.3 PLUMBING

Provide gooseneck, single lever faucets with high limit temperature control for

all hand basins.

14.7.4 ELECTRICAL

Locate electrical outlets in sufficient number to prevent unnecessary extension

of cords for equipment and fixtures.

43

Install safety coverings on all electrical outlets not in use.

Ensure safety of children when specifying electric baseboard heaters.

Consider location of lighting in relation to security cameras.

Establish location for security monitor and recording device. Remote latches,

auto door openers, and intercom must also be coordinated with each other as

part of the entire system.

Consider use of sound monitoring devices in areas such as the sleep

room/area. Fire

Ensure heat detectors, smoke alarms, and carbon monoxide detectors are

installed in locations as required by OBC and local Fire Department. If

sprinklers are required ensure that adequate coverage is provided to all areas,

including storage rooms and closets.

Supply and install fire extinguishers.

Prepare and post a fire safety and emergency plan.

Safety plan to be submitted to Local Fire Department for approval.

The approved Fire Safety Plan must be used to prepare and post a fire safety

and emergency plan.

Ensure areas for posters, artwork, etc. do not exceed permitted wall area for

combustible materials. Consult with local Fire Department.

14.7.5 PROJECTIONS AND FURNITURE PLACEMENT

Controls of casement type windows tend to be at childrens eye level and may

cause injury.

Avoid window projections into room and outer playground. 44

44

Avoid protruding window sills with square edges.

All fire exists must remain accessible in the case of an emergency, this is a

Fire Code Requirement. Design entrance ways, corridors and all required exits

large enough to ensure furnishings, equipment, strollers etc. that are used in the

day-to-day activities of the centre have adequate space.

Ensure furnishings do not obstruct barrier free path of travel.

Secure furniture such as book cases or other items that could topple directly

off the wall.

Select place and design furnishings in a manner that dont create a hazard for

children. For example, do not have openings of a size where a child may get

their head stuck.

Carefully consider location of bulletin boards, dispensers or other objects that

have materials or contents that may spill, become detached or grabbed by

children.

14.8 FURNISHINGS

Indicate furniture layout on concept drawings. Selected equipment and

furnishings to be

co-coordinated with respect to electrical locations requirements, phone outlets

and data wiring. Furnishings and equipment should fit into proposed space.

When designing or purchasing moveable furnishings, ensure they are sturdy

and not prone to toppling.

Consider floor space and storage requirements for furnishings that are to be

stored or folded away.

45

15. LANDSCAPE CONSIDERATIONS

Landscaping is a vital part of an outdoor play environment and is

complementary to all types of play activities. Landscape design should consider

the:

Topography.

A variety of colours, textures, and surfaces.

Protection from the sun, wind, and noise.

Select plants that are responsive to the changing seasons. Design proper

drainage of all surfaces.

Rocks and Debris

During the construction of a play area, remove all rocks and debris larger than

100mm (4 in.) to a depth of 300 mm (1 ft).

Drainage

Slope grade of playground away from the building.

Provide either concrete curbs, logs, or timbers around sand areas to seal in

water and impede drainage. Avoid locating sandboxes below ground level as

this creates the potential for a child to fall in.

Avoid crossing play areas with drainage swales which might cause children to

fall.

Provide a drainage system so that the playground is not greatly affected by wet

weather.

Drainage is important in sand play areas as well as the ground under the swings

and slides as these areas tend to become the lowest points.

46

Recommended Surface Slopes for Drainage are:

0 to 2% slope for resilient surfacing, provided with under drainage.

2% minimum slope and cross-slope for asphalt surfaces.

1% minimum slope for concrete surfaces.

2% minimum slope for open lawn areas.

Maximum 5% longitudinal slope for paved areas.

Grass Hills and Slopes

If space permits, provide a grassy hill, natural or constructed, as part of each

play area.

Typical earth-form slopes should not exceed:

3:1for movable grass areas.

2:1 for cut of fill slopes with erosion-control matting and special non-movable

ground covers.

16. EXTERIOR DESIGN AND PLAY ELEMENTS

16.1 ACTIVE PLAY

The active play area of a playground should consist of both a physical play area

and a social play area. This will allow children to have the opportunity to

develop gross motor skills and to socialize with other children.

The equipment in the physical play area should provide challenges which

promote childrens overall development without creating hazards. The design of

this area should allow for sequential movement from activity to activity.

47

16.2 PHYSICAL PLAY AREA