Professional Documents

Culture Documents

L2 - Envelopes, Noise PDF

Uploaded by

Mrmusician010 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

41 views28 pagesThe envelope of a sound is the change during the course of time of any aspect of that sound. A sound's envelope is the change in pitch, timbral content, duration, loudness. An envelope generator is a tool that can be used to generate envelopes.

Original Description:

Original Title

L2_Envelopes, Noise.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe envelope of a sound is the change during the course of time of any aspect of that sound. A sound's envelope is the change in pitch, timbral content, duration, loudness. An envelope generator is a tool that can be used to generate envelopes.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

41 views28 pagesL2 - Envelopes, Noise PDF

Uploaded by

Mrmusician01The envelope of a sound is the change during the course of time of any aspect of that sound. A sound's envelope is the change in pitch, timbral content, duration, loudness. An envelope generator is a tool that can be used to generate envelopes.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 28

Anglia Ruskin University

Creative Music Technology

Tutor: Julio d'Escrivn

j.d'escrivan@anglia.ac.uk

01223 363271 ext 2978

Sound and Synthesis

MUB2004

Week 3

Lesson 2

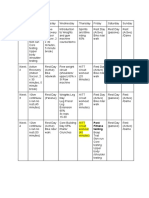

In Class we will have covered the following topics:

Envelopes, stages and Envelope Generators. Noise ugens

CAVEAT (a latin word, yes, look it up!)

The following tutorial is only meant as an accompaniment to the class delivered by

the tutor as part of the course in basic sound and synthesis, MUB2004 delivered at

Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge. It can still be of help to people who are not

taking the course, but it may not serve as a standalone tutorial to supercollider if

you are using it on its own. On the other hand if you have initiative and you use the

other supercollider tutorials available on the net, this can be a good starter into

Sound and Synthesis for newbies. It tries not to presuppose any computer

programming experience. It often explains the seemingly obvious (to advanced

users). If you are a newbie and not afraid to admit it, then WELCOME I wrote this for

us ;)

/*

SECTION I.

Envelopes

The word "envelope" comes from Old French, meaning to wrap

something up. In our time it has come to mean many things, from those

paper pockets you put letters in, to the maximum performance limits of

an aircraft. The thing is, how does it apply to sound? How can

something which brings to mind the covering or wrapping of an object

apply to intangible sound? Well, I'm afraid there is no way around it...

the more you think about it, the more it will become clear. The envelope

of a sound is almost a philosophical concept: the sonic phenomena

limited by it's physicality: its pitch, its timbral content, its duration, its

loudness. Hard work, hey? ok, here is a simpler concept, although one

harder to reconcile with the etymology ( origin! ) of the word; An

envelope of a sound is the change during the course of time of any

aspect of that sound. It may not refer us back to the everyday use of

the word, but at least we can have a clear concept.

Following this denition, the Amplitude envelope is the change in

volume of the sound while we can hear it. So if the volume of a sound

grows over time and then after reaching a certain volume it starts

getting quiet, until it dissapears, the amplitude envelope of that sound is

the story of this change. To tell this story, we use a simple drawing, one

that shows, in respect of the duration of the sound(time) how the

volume has changed. I guess if you drew the story of the sound told

above, you'd get a chinese hat ! (a triangle shape, right?).

How about if the sound grows from silence, reaches a peak and then

decays to a point where it remains for a while before dying off? To

describe the way the sound changed, we'd draw something like you

will nd in the illustration below:

the different stages of growth/decay of the sound we could call by

some commonsense names: attack, decay, sustain and release. And if

we can describe an envelope with just these four stages, then we can

call it an ADSR envelope after the initials of the word that describes

each stage..

This behaviour is a simple model of what happens in real life (which is

always far more complicated). If you are a bass player, for example

and do some Bass slapping techniques, you will know that the loudest

point of the sound comes very near the beginning (after you manage to

pull and release the string, but the loudest is when you release it and it

slaps against the ngerboard: releasing the string makes a quick sound

follwed by a loud slap), then, that the sound decays to a point where

we still hear it for a while before it starts to die away. Ok, so what use

is this to us? Well, up to now, we've been switching sounds ON and

OFF, almost literally; But this is clearly a limited way of playing a sound.

It would be nice if we could control how the sound appears and what

changes it goes through during it's existence, right?

Let's see how we can create envelopes in supercollider.

Do you remember the discussion on "nesting" in lesson1? (if you don't,

this is a really good time to open that le and go over them again,

otherwise you will understand nothing that follows :0 )

Well, we have already used a very simple kind of envelope, it was a

very simple story line... the value started high and got low over time...

still don't remember?

ok, here it is:

{SinOsc.ar(freq: XLine.kr(2000,200,5), phase: 0, mul: 0.5, add:

0)}.scope;

We nested the XLine unit generator (don't you just love that name?) or

UGen, in the 'freq' slot, so that over 5 seconds, the frequency value

would drop from 2000Hz to 200Hz. In doing that, we created a

"frequency envelope" better known in the industry as a "pitch

envelope".

Ok, so far so good (I can only hope !). But there must be lots of

different envelopes we could use, right? In the same way that

perhaps, when you were in primary school the rst thing you learn to

draw is a stright line ( or an XLine !), and then by putting lines together

you could make shapes such as a rectangle, a square or a triangle, and

then later on, you used these shapes to represent things in real life,

such as a shoe box, a TV screen or a chinese hat (!) , we will now

proceed to use a UGen that will allow us to connect lines together to

make our sounds behave in a more realistic fashion.

In order to look at envelope shapes and test them, we will use two

appropriately named messages: plot and test. The word "plot", if you

look it up on the internet in say, dictionary .com, has many related

meanings, one of them has to do with story lines which is appropriate to

our explanations, but the one that bes suits how we use this message is

"To represent graphically, as on a chart: plot a ship's course."

... and "test", which if you also look it up in the dictionary will have

many meanings but my favourite is extrapolated from those by looking

at the latin word "testis" which means someone who is a witness to the

truth of something.

So, armed with these two powerful tools, to draw and to witness, to

represent and to give account, to PLOT and to TEST, let's just do it !

Here is a new object, it is called Env.

At this point, have you noticed that all objects start with a capital letter?

i.e SinOsc, Env, XLine... and that all messages are written in lower

case? i.e. play, scope, ar, kr... this is actually a rule in Supercollider.

Ok, back to Env. It is an 'object', we can ask supercollider to give us

one of these objects by using a further message: 'new'.

Make sure both the internal and localhost server are running and then

evaluate this (highlight and press ENTER):

Env.new([0,1, 0.3, 0.8, 0], [2, 3, 1, 4],'linear').test.plot;

Can you guess what is happening?

This much seems clear:

1. We are plotting or drawing something and we are being able to

listen (test) that drawing.

2. We have an new Env object with a bunch of numbers and the word

"linear" (from "line") !

Before we actually explain what these numbers are, why don't you

spend some time evaluating in turn the following lines of code

Env.new([0.001, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0.001], [2, 3, 1,

4],'exponential').test.plot;

Env.new([0, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0], [2, 3, 1, 4],'sine').test.plot;

Env.new([0.001, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0.001],[2,3,1,4],'welch').test.plot;

Env.new([0, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0], [2, 3, 1, 4],'step').test.plot;

Env.new([0, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0], [2, 3, 1, 4], -2).test.plot;

Env.new([0, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0], [2, 3, 1, 4], 2).test.plot;

Env.new([0, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0], [2, 3, 1, 4], [0, 3, -3, -1]).test.plot;

You must've come to some conclusions by now, right? plot draws the

graph, test plays a sinewave with its volume changing in the shape of

the graph, the green word or number outside the square brackets

affects the shape of the lines giving them degrees of 'curviness', and the

bunch of numbers are somehow the values for the peaks and troughs

of the graph and the distances between these... did you come to these

conclusions? If you didn't go ahead and evaluate again the lines of

code above. We'll wait for you right here !

Glad to have you back, ok, rst lets look at the bunch of numbers. They

are called "arrays" which is geek for "an ordered bunch of things". Of

key importance here is the fact that they are ordered. Later on you will

see that it's not just numbers you can have in an array, but for now,

let's limit ourselves to numbers, ordered numbers.

So, let's take it apart:

Env.new([0.001, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0.001], [2, 3, 1,

4],'exponential').test.plot;

There are two arrays inside our Env.new:

Env.new([0.001, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0.001], [2, 3, 1, 4],'linear').test.plot;

The rst array is made up by the amplitude peaks and troughs of the

envelope: starting at a volume level(amplitude) of 0.001, which is very

quite, the volume grows to 1, then decays to 0.3, then grows again to

0.8 and then decays back to 0.001.

The second array is made up of the times it takes to go between the

peaks and troughs described in the rst array so if we look closely this

is what happens:

Starting at a volume level(amplitude) of 0.001, the volume grows to 1

(which from the graph, we can tell is the loudest volume possible) over

the course of 2 seconds, then decays during 3 seconds to 0.3, then

grows again during 1 second to 0.8 and then decays back to 0.001

over the course of 4 seconds.

Notice that there are 5 values in the rst array and only 4 values in the

second. It is rather like making a hotel reservation for the holidays, if

you are staying 3 days, it means you will stay for 2 nights ! think

about it...

Run through the code examples above again and this time see how the

numbers make sense.

We can control the way the the volume grows by telling the Env object

what kind of line we want, compare these two:

Env.new([0.001, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0.001], [2, 3, 1,

4],'exponential').test.plot;

and

Env.new([0.001, 1, 0.3, 0.8, 0.001], [2, 3, 1, 4],'linear').test.plot;

in the code which says 'linear', the lines are straight. In the code which

says "exponential" the lines are curvy. Exponential comes from

exponential mathematical functions, but for us all it means is that the

curve is gradual to begin with and then gets really steep quite soon.

You can explore the other types of curves in the examples I gave you

before, it is good to know them as they will come in handy later on.

Notice that in our plots, the loudest volume is the value 1. The lowest

volume is the value 0.

Every peak or trough in the plot is called a "node". This is a good word

to know. We can designate nodes for two special roles:

1. looping: so that a section of our graph can be designated to repeat

2. releasing: so that we can stay at that value untill Env receives a

release command.

these last two possibilities we will examine later, for now let's make

some noises...

Here is a simple envelope, before we use it lest test and plot it:

Env.new([0, 1, 0],[1.0, 1.0], 'sine').test.plot;

Ok, now, since we know all about nesting, lets nest it inside a SinOsc

ugen, to do this we need a "wrapper" to make the Env send values we

can use. This wrapper is EnvGen. It is short for "Envelope Generator"

or a thing that generates, creates and envelope. We give it the recipe

with our Env.new and then it proceeds to generate the envelope from

this recipe.

Here we go, instead of playing, we will scope it in order to be able to

see what is happening:

(

{SinOsc.ar(

freq: 440,

phase: 0,

mul: EnvGen.kr(Env.new([0, 1, 0],[1.0, 1.0], 'sine'))

)

}.scope

)

we can make this look even clearer if we break up the lines like so:

(

{SinOsc.ar(

freq: 440,

phase: 0,

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.new([0, 1, 0],[1.0, 1.0], 'sine')

)

)

}.scope

)

before we go any further, I need you to try plugging this envelope into

Pulse and Saw. You will probably miss a coma or a parenthesis here

and there and supercollider won't run untill you type it perfectly, so this

is good practice for you and it will allow you to let the knowledge sink

in a bit more, so go ahead. Never be afraid to try the obvious.

Notice that EnvGen is being sent the message "kr". Try it with "ar", can

you hear any difference?

Also, did you see how it is quite convenient that the values that 'mul'

expects are between 0 and 1, because our EnvGen will only output

values between 0 and 1 anyway?

Ok, so how could we make this work for frequency? Could we just plug

our EnvGen into freq?

What range of values does frequency expect? (hint: what is the range

of human hearing?)

if you can answer these questions then you will understand why, in the

example below, we are multiplying our EnvGen by the number 500.

Two things: rst, yes we can multiply UGens by numbers in

Supercollider because UGens produce numbers anyway. Second, 500

is a number from the range of possible values that freq expects to have.

(

{SinOsc.ar(

freq: 500*EnvGen.kr(

Env.new([0, 1, 0],[1.0, 1.0], 'sine')

),

phase: 0,

mul: 0.5

)

}.scope

)

Let's do a brief recap. Envelopes are the change during the course of

time of any aspect of a sound. We create envelopes by dening these

changes with two arrays of numbers, the rst array tells us the values to

change to, and the second array lists the times it will take to change

between these values. A key word such as 'linear' or 'exponential' tells

us how fast values will change between points, These points are called

nodes. Envelopes are like recipes which must be carried out at audio or

control rate (ar or kr, but we can't seem to tell the difference when we

listen to them, actually). In order for these recipes to be carried out, a

ugen appropriately called EnvGen must receive the recipe. EnvGen

can be plugged in to 'mul' directly because mul expects numbers

between 0 and 1, and it so happens that this is what EnvGen does, it

generates numbers between 0 and 1, according to the Env recipe. Env

generator must be 'scaled' (rst time I use this word, but it is quite

important) which means, to be brought into an audible range if we want

to use it to create a pitch envelope. One way we can do this, is by

multiplying the EnvGen by a number between 20 and 20.000 because

then the result will be in the range of audible frequencies.

***factoid: in commercial synthesizers you will nd that envelopes

have maybe four or ve available stages at most, Attack-Decay-Sustain-

Release, or Attack-Hold-Decay-Sustain-Release, or some variation of

this, but in supercollider your envelopes have as many stages as you

want!***

For now, let's look at some more amplitude envelopes. In real life, there

are only two types of envelopes, those that when triggered have a set

duration and those whose duration we can control. The former are

called Fixed envelopes and the latter are called Sustained envelopes.

Think about this for a moment and see if you can nd some examples...

If you hit a snare drum, the sound will grow in volume so quickly that it

will sound instantaneous. But you have no control over how fast it dies

away. It just dissapears as fast as it came ! That would be a sharp-

attack fast-release amplitude envelope. Now, if you play a violin, the

sound will be sustained for as long as you bow... you are in control of

the 'release node' ! when you stop bowing, the sound stops. The snare

drum has a xed envelope. The violin has a sustained envelope,

meaning we can sustain it for as long as we want (or can !).

There are some preset envelopes that can be made with the Env object.

We used Env.new to make them from scratch, but the following xed

envelopes are also available, let's try them out:

Env.triangle(1, 1).test.plot;

and if we plug it in to mul:

(

{SinOsc.ar(

freq: 440,

phase: 0,

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.triangle(1, 1)

)

)

}.scope

)

or in a Pulse wave... (can you remember which parameters Pulse

takes?)

(

{Pulse.ar(

freq: 440,

width: 0.5,

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.triangle(1, 1)

)

)

}.scope

)

Change the values for the triangle preset and see what they do... if you

give up you can always check the help le (this is a good time to

remember how that's done!).

Here's another one:

Env.linen(1, 2, 3, 0.6, 'sine').test.plot;

try changing the values above to nd out what they do.

now plug it in to a sawtooth wave and you can observe the effect:

(

{Saw.ar(

freq: 440,

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.linen(1, 2, 1, 0.6, 'sine')

)

)

}.scope

)

Here's yet another one:

Env.sine(1,1).test.plot;

Test it to see what the values do and then... you guessed it, plug it in!

(

{Saw.ar(

freq: 440,

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.sine(1,1)

)

)

}.scope

)

And another one:

Env.perc(0.05, 1, 1, -4).test.plot;

don't dismiss this last one too quickly, the help le shows some

interesting settings, but rst do nd out what they do for yourself.

to showcase this one, let's plug it into a new ugen... WhiteNoise.

(

{WhiteNoise.ar(

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.perc(0.05, 1, 1, -4)

)

)

}.scope

)

isn't it ideal for checking out this envelope? White noise only wants to

know what amplitude you want so we plug in right there in 'mul' and it

works great...

I like the following settings:

(

{WhiteNoise.ar(

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.perc(0.5, 0.01, 1, 4)

)

)

}.scope

)

And now for something completely different ! Well not that different, in

fact: Sustained envelopes. The thing here is that we need to send some

kind of signal to the envelope so it knows how long to sustain for !!

To make things simpler, to begin with, let's just use the 'test' message,

because it has a nice little feature that allows us to send a sustain time...

there are three of these sustained envelopes, i will give you the

parameters this time:

Here it is from the help le:

Env.adsr(attackTime, decayTime, sustainLevel, releaseTime, peakLevel,

curve)

Creates a new envelope specication which is shaped like

traditional analog attack-decay-sustain-release (adsr)

envelopes.

attackTime - the duration of the attack portion.

decayTime - the duration of the decay portion.

sustainLevel - the level of the sustain portion as a ratio of the

peak level.

releaseTime - the duration of the release portion.

peakLevel - the peak level of the envelope.

curve - the curvature of the envelope.

Env.adsr(0.02, 0.2, 0.25, 1, 1, -10).test(2).plot; //sustains for 2 secs

Env.adsr(0.001, 0.2, 0.25, 1, 1, -4).test(2).plot; //sustains for 2 secs

Env.adsr(0.001, 0.2, 0.25, 1, 1, -1).test(0.45).plot; //sustains for

0.45 secs

experiment with different values for the curve of the envelope as this

may seem like the least obvious of the values presented.

And now, let's do a plug-in:

(

{WhiteNoise.ar(

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.adsr(0.02, 0.2, 0.25, 1, 1,

-10), MouseX.kr(-0.1, 0.1)

)

)

}.scope

)

Did you notice something different in the code? I happened to write

something new inside the EnvGen: the trigger.

Try moving the mouse from left to right and back again, accros the

center of the screen and see what happens. Now change the values of

the ADSR envelope and see what happens.

The trigger is the signal that EnvGen is waiting for to activate the

envelope. It is very simple. If the value at that slot is greater than zero,

then, the Envelope gets started. If the value falls to zero or below zero

then the release portion of the envelope gets underway and the

envelope dies out at whatever duration you set. Try it again. Remember

that until you turn off the the Ugen with a 'command+dot' the mouse

will keep triggering the sound ! -it can get on your nerves pretty quickly-

In the example above, the mouse's horizontal range is set to go

between -0.1 and 0.1, for this reason each time we cross the screen

from left to right, the mouse sends out a value above zero, a positive

value. Everytime the mouse crosses the center of the screen from right

to left, the mouse falls below zero. Consequently, mousing to the right

starts the sound and it sustains while you are on the right side and

when you mouse back to the left, the sound is stopped (but the

synthesizer keeps running!!! it's like you may not be playing it but it is

still switched on.)

Here is another envelope with sustain:

Env.asr(attackTime, sustainLevel, releaseTime, peakLevel, curve)

Creates a new envelope specication which is shaped like

traditional analog attack-sustain-release (asr) envelopes.

attackTime - the duration of the attack portion.

sustainLevel - the level of the sustain portion as a ratio of the

peak level.

releaseTime - the duration of the release portion.

peakLevel - the peak level of the envelope.

curve - the curvature of the envelope.

Env.asr(0.02, 0.5, 1, 1, -4).test(2).plot;

Env.asr(0.001, 0.5, 1, 1, -4).test(2).plot; // sharper attack

Env.asr(0.02, 0.5, 1, 1, 'linear').test(2).plot; // linear segments

let's plug it in and use the same mouse trigger thing:

(

{WhiteNoise.ar(

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.asr(0.02, 0.5, 1, 1, -4),

MouseX.kr(-0.1, 0.1)

)

)

}.scope

)

and... the last envelope, I priomise (for now at least):

Env.cutoff(releaseTime, level, curve)

Creates a new envelope specication which has no attack

segment. It simply sustains at the peak level until released.

Useful if you only need a fadeout, and more versatile than

Line.

releaseTime - the duration of the release portion.

level - the peak level of the envelope.

curve - the curvature of the envelope.

Env.cutoff(1, 1).test(2).plot;

Env.cutoff(1, 1, 4).test(2).plot;

Env.cutoff(1, 1, 'sine').test(2).plot;

and we can plug it in:

(

{WhiteNoise.ar(

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.cutoff(1, 1, 'sine'), MouseX.kr

(-0.1, 0.1)

)

)

}.scope

)

and now for some cool trigger ideas.

How about pluging in a ugen that sets off triggers on its own? Here's a

couple of candidates:

{Impulse.ar(4, mul:0.5)}.play; //constant clicks are heard... at the rate

set by the rst number

{Dust.ar(5)}.play; //the density of clicks per second is the only value

you give this one

ok, so electronica enthusiasts should be salivating by now ! ;)

let's plug this in to one of our examples from above: (but for variety I

will use another noise ugen:

(check out the help le for it, it's pretty basic). Also, and please note,

instead of audio rate or 'ar' which I used to test these triggering ugens

above, we should use 'kr', in this case it does make a difference. Follow

this rule: if you are using the ugen to make a sound wave directly then

use '.ar', if you are using the ugen to control or trigger something, then

use '.kr'.

(

{PinkNoise.ar(

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.perc(0.05, 1, 1, -4), Dust.kr(5)

)

)

}.scope

)

and this one:

(

{PinkNoise.ar(

mul: EnvGen.ar(

Env.perc(0.05, 1, 1, -4), Impulse.kr

(5)

)

)

}.scope

)

At the end of this section you should be

able to:

1. Explain in your own words the following concepts:

-Envelopes

-Nesting

-Linear

-Exponential

-Arrays

-Triggering

2. Create lines of code using the following UGens:

-Env

-EnvGen

-WhiteNoise

-PinkNoise

-Impulse

-Dust

3. Competently use the following messages/methods:

( a method is the way that the messages we send to the ugens are

implemented, it is the activity they do when they receive a message)

-plot

-test

-new

-triangle

-linen

-sine

-perc

-adsr

-asr

-cutoff

Exercises for you to do:

1. Create a line of code for each ugen and method you have learnt.

2. try layering different soundwaves with different envelopes, see if you

can make some interesting sounds. Record anything that seems

promising, you may want to use it later...

3. set off more than one noise at different Impulse rates to get rhythmic

patterns going

SECTION II

Noise

Noise is a very interesting form of sound. It is what we call sound that is

apparently random, that we can nd no pattern in. Of course, we also

use it to mean sounds that are unpleasant to us, in fact maybe because

of their apparent randomness? Some people, when they don't like a

piece of music, they refer to it as noise... this is what a lot of

Beethoven's contemporaries thought of his 9th Symphony and it is what

some think of Ligeti's "Atmospheres". When sound makes no sense to

us, we call it noise. Perhaps precisely because of this, we must have a

closer look... (As perhaps the things we don't like tell us more about

ourselves than the things we like! )

In Supercollider there are a few unit generators that can be used to

create noise, here is one:

{ WhiteNoise.ar(0.2) }.scope(1); //what does it sound like?

Think about it for a moment, what does it sound like? fast sandpaper

scraping? the surf part of a wave at the seaside? Your TV after

programming ends or tuned to a nonexistent channel?(actually the

latter may be an old-school experience exclusively, but nevermind! )

Have a look at the Stethoscope window, can you see any patterns?

Compare to this:

{ Saw.ar(261)}.scope; //a sawtoothwave.

Now that's more like it, no? A proper predictable soundwave that

draws a nice clear patter on the screen ! (just kidding !) the difference

is quite clear, the one called "white noise" is putting out a pattern which

never repeats in the same way, this means it is APERIODIC meaning

that it has no period or predictable repeating portion. Sounds like the

Sawtooth wave above are PERIODIC because they repeat in a

predictable way. Let's look at this white noise in greater detail:

{ WhiteNoise.ar(mul: 0.2) }.scope(1); //play it again just for a laugh!

ok, white noise is dened as a kind of noise (seemingly random

waveform) that generates all frequencies possible and all at the same

loudness or amplitude. No particular area of the frequency spectrum is

emphasized. Did I say Spectrum? This is an important word for

electronic musicians, I think the most general meaning is:

"A broad sequence or range of related qualities, ideas, or activities: the

whole spectrum of 20th-century thought." (the whole spectrum of my

wardrobe, for example?)

and in physics it means:

"The distribution of a characteristic of a physical system or

phenomenon"

Dictionary.com

Easier: of all the available frequencies that the human ear can perceive

(the spectrum of audible frequencies) in "White Noise" we hear them

all at the same volume. There is no emphasis on low frequencies, for

example. It is a kind of democratic noise, don't you think so?

It is easy to remember how play it in supercollider because it only takes

two parameters, amplitude and offset or, to start speaking the lingo,

"mul" and "add".

The format for this UGen is:

WhiteNoise.ar(mul, add)

Remember the way supercollider looks at the parameters for UGens

(let's call them arguments from now on):

-if an argument appears like so, on its own, lonely like a dog:

{ WhiteNoise.ar(0.2) }.scope(1);

Supercollider (SC to its friends) knows that it is the argument for 'mul'.

-if the arguments appear like so

{ WhiteNoise.ar(0.2,0) }.scope(1);

SC knows that the rst value is for 'mul' and the second for 'add'

-if the arguments appear with keywords, like we explained in

StudyNotes-1, then it doesn't even matter what order we put them in,

as they have their neat little labels anyway !

{ WhiteNoise.ar(mul: 0.2, add: 0) }.scope(1);

Try this, change the add value above to the value of 1. Can you predict

what will happen in the scope? Now change it to -1, can you predict

what will happen now?

There are other avours of noise, which have colour associations ( I

don't know who invented the colour labels but would be interested if

anyone does...). Let's look at some:

PinkNoise.ar(mul, add)

{ PinkNoise.ar(0.4) }.scope(1);

Again, the format is similar to WhiteNoise... so everything above

applies... the difference is that the higher frequencies are dampened or

attenuated(look up this word, you will need it!)

at the rate of 3db per octave... what? db? octave? this last sentence

merits an explanation.

rst 'db' is short for decibel. A decibel is a unit of sound intensity. From a

mathematical point of view it is said to be logarithmic, but to be quite

honest, this is not really important for a musician... HOWEVER you must

understand that it is not linear, i.e. a sound that is 2db louder than

another is not twice as loud! in fact in decibels, 3db means twice as

loud, or twice as quiet. Ah, did I mention it is a relative unit? so it is used

to measure the difference in intensity between two sounds, relative to

each other. As a muso, even if you are an electro-muso, that's as much

as you need to know, the rest you will nd out by experimenting with

ugens that take dbs or when observing the signal level on your

recording software or in your fantastically expensive audio

compressors :)) of course if you happen to have a scientic

background, knowing more won't hurt.

Second, an octave is the difference between a frequency and it's

doubled value above or below, so for example if you take the

frequency for the middle C of the piano, which is 261.62556530114

and you double that to 523.25113060083, this last resulting

frequency corresponds exactly to the next note C immediately above

middle C... If middle C is C3 then the octave above is C4. The concept

of the octave is used to measure accross the sound spectrum, so, if we

go up in octaves from the lowest sound we can hear which is 20hz, we

get this:

20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, 1280, 2560, 5120, 10240, 20480

that last frequency you will be able to hear only if you are a dog... :)

So, if we make noise that gets its frequencies attenuated by 3db every

octave, it follows that the high frequencies are going to end up very low

in volume. This is what denes PinkNoise and it is why it sounds soft or

mufed in comparison to WhiteNoise.

Another type of noise is:

BrownNoise.ar(mul, add)

{ BrownNoise.ar(0.2) }.scope(1);

This one falls in power or intensity by 6db per octave, thanks to the

explanation above, you should now understand what that means.

and nally, for now at least:

GrayNoise.ar(mul, add)

{ GrayNoise.ar(0.2) }.scope(1);

If you read the help le explanation, unless you are an audio engineer

you will be dumbfounded... All you need to know is that it is a bit

crackly and that The spectrum is emphasized towards lower

frequencies.

At the end of this section you should be

able to:

1. Explain in your own words the following concepts:

Noise, periodic, aperiodic.

2. Create lines of code using the following UGens:

WhiteNoise, PinkNoise, GreyNoise, BrownNoise.

3. Competently use the following messages/methods:

( a method is the way that the messages we send to the ugens are

implemented, it is the activity they do when they receive a message):

scope.

Exercises for you to do:

1. Get together with a friend and see if you can recoginze these

different noises without looking at the computer screen at all, you will

also be quizzed on this. A self respecting electronic musician knows his

noise !

2. Also, now that you know all these noise forms, why not use them to

practice your amplitude envelopes, as explained above:

a. Make 3 percussive noise envelopes with different types of noise

b. Using noise make an envelope which mimics the sound of the sea.

3. if you are really adventurous, then try plugin a noise ugen into the

freq part of a soundwave, remember the example where we did that

with the envelope and had to multiply by 500 to get some sound... just

explore that.

*/

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- KDL46W5100Document109 pagesKDL46W5100Tim KochNo ratings yet

- Column Design - at Design OfficeDocument56 pagesColumn Design - at Design OfficeShamen AmarasekaraNo ratings yet

- TitanicDocument6 pagesTitanicTeem ChakphetNo ratings yet

- London Pass ListDocument7 pagesLondon Pass ListkamikazelyNo ratings yet

- Donna Fletcher - Book ListDocument1 pageDonna Fletcher - Book Listjosephine20010% (1)

- Randall Platinum PlanDocument18 pagesRandall Platinum PlanNikal PoudelNo ratings yet

- FEI WDC Elementary TestDocument3 pagesFEI WDC Elementary TestPuertoRicoEcuestreNo ratings yet

- Ts 2014 07 11Document96 pagesTs 2014 07 11jorina807No ratings yet

- In Between Dreams: 4 Charts 5 Certifications 6 Sheet MusicDocument3 pagesIn Between Dreams: 4 Charts 5 Certifications 6 Sheet MusicAndrea Guachalla AlarconNo ratings yet

- Magstripe and Chip Encoding With Edisecure Connect® (V2.3/2.4) SDKDocument2 pagesMagstripe and Chip Encoding With Edisecure Connect® (V2.3/2.4) SDKPedro FrancoNo ratings yet

- Cpar Study GuideDocument10 pagesCpar Study GuideChelsey RotorNo ratings yet

- I Arrive For My Interview With Chloe Kelling and IDocument7 pagesI Arrive For My Interview With Chloe Kelling and IKellyNo ratings yet

- SLR Fitness ProgramDocument5 pagesSLR Fitness ProgramKevin ZuddNo ratings yet

- Vargas Museum Study GuideDocument12 pagesVargas Museum Study GuideRovin James CanjaNo ratings yet

- Trix Nh2017 enDocument124 pagesTrix Nh2017 enacuarelito100% (1)

- Internship Report On Marketing Mix of FODocument34 pagesInternship Report On Marketing Mix of FORiyad HossenNo ratings yet

- 25eff E973Document9 pages25eff E973api-233604231No ratings yet

- HOPE 3 Lesson 1 Elements of DanceDocument29 pagesHOPE 3 Lesson 1 Elements of DanceJay El Taypin OrdanezaNo ratings yet

- Chicken BiriyaniDocument3 pagesChicken BiriyaniTanmay RayNo ratings yet

- The Complete Guide To Creative Landscapes - Designing, Building and Decorating Your Outdoor Home (PDFDrive)Document324 pagesThe Complete Guide To Creative Landscapes - Designing, Building and Decorating Your Outdoor Home (PDFDrive)One Architect100% (1)

- Gaspar Sanz - Matachin - Guitar Pro TabDocument1 pageGaspar Sanz - Matachin - Guitar Pro Tabalexhong155No ratings yet

- Legends, Myth A Guide To Text TypesDocument32 pagesLegends, Myth A Guide To Text TypesAnnyNo ratings yet

- USB Device List For PSR-S650 PDFDocument3 pagesUSB Device List For PSR-S650 PDFmlarangeira7622No ratings yet

- Christina MJ Kim: Sequence of Repertoire - ViolinDocument9 pagesChristina MJ Kim: Sequence of Repertoire - ViolinMiguel VazNo ratings yet

- Transitioning From Outbound To RTM MarketingDocument51 pagesTransitioning From Outbound To RTM MarketingMagicMoviesNo ratings yet

- RH6.5 ProspektDocument14 pagesRH6.5 ProspektEslam FaroukNo ratings yet

- Ennio Morricone-Heres To YouDocument1 pageEnnio Morricone-Heres To YouJorge CamposNo ratings yet

- Recipe # Cream of Tomato (Crème de Tomate)Document3 pagesRecipe # Cream of Tomato (Crème de Tomate)गौ रव कृष्णNo ratings yet

- Polyfab Shade Sail Edge Webbing: Item # Average Breaking Strength Color Color # Put Up WidthDocument6 pagesPolyfab Shade Sail Edge Webbing: Item # Average Breaking Strength Color Color # Put Up WidthTanveer AhmedNo ratings yet

- Daftar Game N-Gage 1.0Document2 pagesDaftar Game N-Gage 1.0mynameisfebNo ratings yet