Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CASES Related Disorders

Uploaded by

Evelyn WeaverOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CASES Related Disorders

Uploaded by

Evelyn WeaverCopyright:

Available Formats

Autism Spectrum Disorders

CASE STUDY

HISTORY

Joey is a 6-year-old boy who was reported to have achieved early developmental motor milestones

within expected age ranges and his early developmental language milestones were within normal

limits as well (e.g., first words at 12 months, two word phrases at 15 months). However, his parents

reported that between 15 and 18 months he gradually stopped playing with his siblings and became

quieter. Also at this time he developed sleep difficulties and extreme tantrum behaviors including

banging his head. By 2 years of age, he was no longer talking and appeared to be "in his own little

world."

Joey began receiving speech/language therapy at age 2 years and his speech/ language therapist

suggested that he be evaluated for autism.

At the time of his diagnosis, shortly after he turned 3 years old, Joey had no speech and was not

pointing or gesturing to indicate his needs. His parents would need to hold things up and give them to

him to try to determine what he wanted or what was bothering him. Joey would not imitate actions of

others around him, nor did he engage in any pretend play or play with other children.

Joey made little eye contact and his parents reported that if they held his chin to try to force him to

look at them, he would look away. Joey did not offer comfort to others and would not accept comfort.

He had a limited range of facial expressions (smiling, scowling, and a "blank" look). Joey had no

interest in and did not respond to the approaches of other people. He would sometimes take his

mothers hand and lead her to what he wanted and put her hand on it. He used her hand as a tool in

other ways as well (e.g., when he would be upset and crying, he would use her hand to wipe his face

instead of his own).

Joey would repetitively pluck the fur off of his stuffed animals (going through two to three stuffed

animals per week) and pluck the fibers from carpets and afghans. He frequently went around the

house and collected everyones shoes and lined them up. He frequently mouthed objects and also

liked to lick windows and glass. Joey had odd hand mannerisms, twisting his hands in front of his face

and eyes. He was also frequently observed to walk on his toes while flapping his hands and spinning in

circles.

DIAGNOSIS

At the time of his initial evaluation he scored in the clinically significant range in all areas on

the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised)(ADI-R). He was also administered Module 1 of the Autism

Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) with scores consistent with Autistic Disorder as well. He was

not able to engage in standardized assessment of his intellectual ability at that time. A nonverbal

measure was attempted but rather than using the response cards to provide responses to test items,

he became fixated on them. Similarly, he became intensely interested in the spiral binding on one of

the stimulus books but was not interested in using the test materials as the examiner asked him to.

Joey was diagnosed with Autistic Disorder.

Teaching Students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder

Case #1: Melodie - Grade 1

Melodie, 6, moved into Metropolis Elementary from Los Angeles in January of her grade one

year. Her mother, a homemaker who appeared somewhat exhausted from managing

Melodie, met with Miss Fontaine, the Grade 1 teacher. She informed the teacher that

Melodie had been on Ritalin since Kindergarten and would need some special attention. She

and her husband, an engineer, were looking for any suggestions the school could provide in

managing Melodie at home as well. Miss Fontaine indicated that she would review Melodie's

file and asked Melodie's mother if she and her husband could come in to meet with her and

the school based team next week to discuss Melodie's program.

During the first week, Miss Fontaine made the following observations:

Melodie is cheerful and friendly. She seems keenly interested in pleasing the teacher

and her classmates.

Melodie appears to have a strong understanding of verbally presented information,

knows her colours and can count to 100.

Melodie's literacy skills are at the emergent stage - she cannot recall letter names

and does not appear to have any sight vocabulary.

Maintaining one to one correspondence with objects while counting is difficult for

Melodie.

Melodie completes 2 out of 20 questions when not medicated (she indicated that she

forgot to take her pill on Thursday morning); she completes entire sheet of 20

questions when she has taken her medication

During both individual and group instruction, Melodie frequently interrupts to ask

unrelated questions and change topics.

When interacting with peers, Melodie constantly changes topics and commonly

leaves an activity or game while others continue to play.

Information from Melodie's file indicated that she had received a psychological assessment

and had been identified as having AD/HD as well as learning disabilities. She had been

placed on a wait list for a special class placement in Los Angeles.

Miss Fontaine brought Melodie's case forward to the school based team meeting so that

planning could take place immediately. Mr. and Mrs. Marshall were invited and were able to

meet with the team on Thursday of the second week Melodie had been enrolled at the new

school.

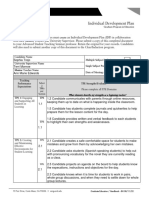

At the meeting, the team agreed that acquiring literacy skills and helping Melodie to focus

on the topic at hand were the most important goals to begin with. The following plan was

developed.

Anderson: Excitement and Joy Through Pictures and Speech

by Sylvia Diehl

Anderson is a 3-year-old boy with ASD who was referred to a university speech and hearing center

by a local school district. He attended a morning preschool at the university center for one year in

addition to his school placement.

History

Birth and Development

Anderson was a full-term baby delivered with no complications. Anderson's mother reported that as

a baby and toddler, he was healthy and his motor development was within normal limits for the major

milestones of sitting, standing, and walking. At age 3 he was described as low tone with awkward

motor skills and inconsistent imitation skills. His communication development was delayed; he began

using vocalizations at 3 months of age but had developed no words by 3 years.

Communication Profile at Baseline

Anderson communicated through nonverbal means and used communication solely for behavioral

regulation. He communicated requests primarily by reaching for the communication partner's hand

and placing it on the desired object. When cued, he used an approximation of the "more" sign when

grabbing the hand along with a verbal production of /m/.

He knew about 10 approximate signs when asked to label, but these were not used in a

communicative fashion. Protests were demonstrated most often through pushing hands. Anderson

played functionally with toys when seated and used eye gaze appropriately during cause-and-effect

play, but otherwise eye gaze was absent. He often appeared to be non-engaged and responded

inconsistently to his name.

Assessment

The Communication Symbolic and Behavior Scales Developmental Profile (CSBS DP; Wetherby &

Prizant, 1993) was used to determine communicative competence. This norm-referenced instrument

for children 624 months old is characterized by outstanding psychometric data (i.e.,

sensitivity=89.4%94.4%; specificity=89.4%). Although Anderson was 36 months old, this tool was

chosen because it provides salient information about social communication development for children

from 6 months to 6 years old.

Intervention

Anderson's team and family members developed communication goals that included spontaneously

using a consistent communication system for a variety of communicative functions and initiating and

responding to bids for joint attention. Research suggests that joint attention is essential to the

development of social, cognitive, and verbal abilities (Mundy & Neal, 2001).

Because Anderson could not meet his needs through verbal communication, AAC was considered.

He had been taught some signs but did not use them communicatively. More importantly, his motor

imitation skills were so poor that it was difficult to differentiate his signs. His communication partners

would need to learn not only standard signs, but Anderson's idiosyncratic signs. Therefore, the

Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS; Bondy & Frost, 1994) was chosen to provide him

with a consistent communication system. Additionally, a visual schedule was used at home and

school to aid in transitions and to increase his symbolization.

Incidental teaching methods including choices and incomplete activities were embedded in home

and preschool routines. In addition, a variety of joint activity routines (e.g., singing and moving to

"Ring Around the Rosie" or "Row Your Boat" while holding hands) that were socially pleasing to

Anderson were identified. These were infused throughout his day in various settings and with

various people. Picture representations of these play routines also were represented in his PECS

book.

Research

Several evidence-based strategies were chosen to support intervention, including PECS (Carr &

Felce, 2007; Ganz & Simpson, 2004; Temple, 2007), visual supports (Bryan & Gast 2000; Krantz,

MacDuff, & McClannahan, 1993), and incidental teaching (Cowan & Allen, 2007; Miranda-Linne &

Melin, 1992).

Outcomes

By the end of the year, a video taken at preschool showed that Anderson was spontaneously using

PECS for requests and protests. He was using speech along with his PECS requests in the "I want"

format. He also used speech alone for one-word requests and for automatic routines such as

counting or "ready, set, go." He shared excitement and joy in several joint activity routines with

various people and referred to their facial expressions for approval and reassurance.

Sylvia Diehl, PhD, CCC-SLP, is an assistant professor in the Communication Sciences and

Disorders Department of the University of South Florida, where she teaches courses in

augmentative and alternative communication, language disorders, autism, and developmental

disabilities. Contact her atdiehl@cas.usf.edu.

Tait: Communicating Emotions

by Jane Wegner

Tait is a 12-year-old boy who was diagnosed with ASD at age 2. Tait is generally healthy although

he has recently been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and is sensitive to pain. He has difficulty

with small spaces and "bottlenecks" where many people are congregated. Tait participates in special

education at a local elementary school. His strengths include being curious, social, and visually

astute. His challenges include communication, impulsivity, and behavior that may include tantrums,

aggression, and property destruction. These challenges have made it difficult for Tait to participate in

activities with peers.

Communication Profile

Tait has a positive-behavior support team and receives speech-language intervention at the

Schiefelbusch Speech-Language-Hearing Clinic. He is a multimodal communicator whose verbal

communication is not understood by most people. He uses a Palm 3 (Dynavox Technologies),

pictures, idiosyncratic signs, gestures, and some words to communicate.

Assessment

Tait's communication was assessed with the SCERTS Assessment Process (SAP; Prizant,

Wetherby, Rubin, Laurent, & Rydell, 2006) in spring 2007. As a criterion-referenced, curriculum-

based tool, the SAP determines a child's profile of strengths and needs based on his or her

developmental stage in the domains of social communication and emotional regulation. Tait was in

the Language Partner stage of communication. We collected data in three contexts: school, home,

and an intervention session in the Schiefelbusch clinic.

Social Communication

Tait's strengths in the area of social communication included engaging in reciprocal interactions,

sharing attention to regulate the behavior of others, and using several modes of communication. His

needs in social communication included sharing a range of emotions with symbols and sharing

intentions for joint attention by commenting on objects, actions, events, or requesting information

across partners and contexts.

Emotional Regulation

Tait's emotional regulation strengths included responding to assistance from a familiar partner that

he trusted, recovering from extreme dysregulation with support from a familiar partner, and using a

behavior strategy (holding a block of wood) to remain focused and calm in some familiar

environments. His needs in the area of emotional regulation were seeking assistance with emotional

regulation from others, responding to assistance across contexts, and responding to the use of

language strategies across environments.

Transactional Support

Transactional support was strong in some areas. For example, all of Tait's partners wanted him to

learn and communicate more conventionally and he had consistent, responsive communication

partners at home. Tait needed the same responsive style across all partners and the consistent use

of visual and organizational supports as well as his AAC system to enhance learning and

comprehension of language and behavior.

Intervention

Goals included:

Increased use of emotion words on the AAC device.

Commenting on objects, actions, or events.

Choosing what he needs to calm himself from choices offered (from an adaptation of the 5-

point scale by Buron and Curtis, 2003).

Transactional goals included:

Using augmented input (Romski & Sevcik, 2003) with redirection, expansion, and modeling

by Tait's partners.

Providing a binder with a schedule and social stories (Gray, 1995) for preparation for

activities.

Making an AAC device always available and using an interactive diary developed by his

mother.

These supports were implemented in activities of interest to Tait such as holidays, his life in photo

albums, tools, and events at home.

Outcomes

In the past two years, Tait has made many communication gains. His AAC device has more than

200 pages of icons, which he accesses independently to express feelings. He has told us when he is

angry, happy, sad, frustrated, and sick, and he engages in reciprocal exchanges, commenting on the

shared object or event of interest. He has started to mark tense when he comments by using the

"later" and "past" icons on his device to clarify his message. He is able to indicate to his partner what

he needs to calm himself when choices are offered. In addition, he has more communication

partners who are responsive and able to provide him with the learning supports he needs.

Find Out More

View an article and video about Tait.

J ane Wegner, PhD, CCC-SLP, is a clinical professor and director of the Schiefelbusch Speech-

Language-Hearing Clinic at the University of Kansas. She teaches courses in AAC and autism

spectrum disorders and directs the "Communication, Autism, and Technology" and "Augmentative

and Alternative Communication in the Schools: Access and Leadership" projects. Contact her

atjwegner@ku.edu.

Sam: From Gestures to Symbols

by Emily Rubin

Sam is a 16-year-old young man with ASD and significant cognitive delays. As part of professional

development training for his educational team, this speech-language pathology consultant followed

him for 12 months. Sam now attends a public school special day class that offers frequent instruction

in varied settings to foster independence in the community.

History

Birth and Development

Sam was born six weeks premature following his mother's hospitalization for pre-term labor. His birth

history was significant for low birth weight (2 lbs., 10 oz), respiratory distress, intraventricular

hemorrhage, and a neonatal hospital stay of six weeks. He began receiving intervention services at

12 months of age to address speech, language, social-emotional, and cognitive delays. To date,

evaluations yield developmental age equivalents up to the 24-month level. Since birth, Sam's history

is unremarkable for significant medical concerns and he is in good health. He has passed hearing

screenings and wears corrective glasses.

Communication Profile at Baseline

At 14 years, 8 months of age, Sam spontaneously shared his intentions through nonverbal means,

which included facial expressions (e.g., looking toward staff to request a snack), physical gestures

(e.g., pulling his teacher's hands to his head to request a head massage), and more conventional

gestures (e.g., pointing to request and a head shake to reject). He also used unconventional

nonverbal signals that included biting his hand to share positive and negative emotions and pinching

to protest. Sam occasionally used a few verbal word approximations (e.g., "no," "yes," "more," and

"balloon"), the sign for "help," and picture symbols on a voice output device. However, he typically

used these symbols passively, most often in response to a direct verbal prompt from his social

partner (e.g., "Do you want more?").

Assessment

At baseline, the SAP was administered to gather information about functional abilities in daily

activities through observation and a comprehensive caregiver questionnaire. Given his baseline

presentation, the SAP placed him at the Social Partner Stage, a stage that is relevant for individuals

using pre-symbolic communication. With this profile, functional educational goals based upon parent

priorities and evidence-based supports were determined.

Research

The SAP was derived from longitudinal descriptive group research. It enables providers to select

educational objectives that are predictive of gains in language acquisition and social adaptive

functioning (Prizant et al., 2005). Sam's educational team selected objectives shown to predict an

individual's symbolic growth, such as increasing his rate of spontaneous communication and his

range of communicative functions. The team worked to move him beyond requesting objects to

requesting specific people and actions. The SAP also facilitated the selection of evidence-based

supports such as AAC when developing educational accommodations to address these objectives.

Intervention

Sam's Individualized Education Program objectives shifted from those for passive responses (e.g.,

responding to questions such as "Where did you go?") to initiating communication using AAC (e.g.,

requesting help or other actions, expressing emotions, and making choices of coping strategies).

Throughout the day, Sam accessed an emotion necklace of laminated cards. On the front of each

card was a graphic symbol representing an emotional state (e.g., happy, angry, and sad). On the

back were symbols representing words Sam could use to request actions from others (e.g., "high

five" for happy). This support fostered symbolic requests for communicative functions that Sam

already exhibited spontaneously using nonverbal means at baseline (e.g., expressing emotion by

biting his hand and looking toward staff).

During language art centers, Sam engaged in activities designed to elicit more sophisticated

requests for preferred actions. Rather than identifying pictures, he could choose a preferred sensory

activity, such as a head massage, a back rub, or tickling. Color-coded symbols paired with sentence

templates allowed Sam to create his own sentences for functions already exhibited spontaneously

using nonverbal means at baseline (e.g., requesting comfort by pulling his teacher's hands toward

his head).

Outcomes

Sam's first quarterly review occurred around his 15th birthday. Observations and videos revealed a

higher rate of spontaneous bids for communication and the emergence of symbols to express

emotion (e.g., "happy" and "mad"), request coping strategies (e.g., "head squeezes" and "high

fives"), and form simple sentence structures (e.g., "Jim squeeze head" and "Karen rub back"). By six

months post-intervention, Sam began to take turns, requesting interaction using subject + verb

sentences and then responding to interaction. His teacher might request that "Sam rub back" and

Sam would oblige. At 12 months post-intervention, Sam continues to expand his symbolic language

skills and recently began to generalize his sentences to include names of his peers.

Emily Rubin, MS, CCC-SLP, is director of Communication Crossroads, a private practice in Carmel,

Calif. She is an adjunct faculty member at Yale University, where she has served as a member of its

Autism and Developmental Disabilities Clinic. She is a co-author of the clinical manual for the

SCERTS Model, a comprehensive educational approach for children with autism spectrum

disorders. Contact her at Emily@CommXRoads.com.

Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee

ASHA Provides Input to Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee

by Ann-Mari Pierotti

The Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC) was established in accordance with the

Combating Autism Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-416.) The committee coordinates all efforts within the

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) concerning autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The

IACC includes both members representing federal agencies and the public to ensure that

perspectives and ideas are represented and discussed in a public forum.

The IACC mission is to:

Advise the Secretary of Health and Human Services regarding federal activities related to

ASD.

Facilitate the exchange of information and coordination of activities related to ASD among

the member agencies and organizations.

Increase public understanding of the member agencies' activities, programs, policies, and

research by providing a public forum for discussions related to ASD research and services.

ASHA staff has been attending the IACC's meetings, which include presentations and discussions

on a variety of topics such as activities and projects of the IACC, recent advances in science, and

autism policy issues. Catherine Gottfred, 2008 ASHA president, submitted comments to the IACC on

Dec. 12, 2008 emphasizing the critical role of the speech-language pathologists with respect to

assessment and treatment of ASD. During this comment period, ASHA informed the committee of

ASHA's policy documents related to the role of the SLP with respect to autism. These documents

include a position statement, technical report, guidelines, and a knowIedge and skills statement and

are available online.

Additionally, ASHA staff provided input to the IACC as the agency developed its 2010 Strategic Plan

for Autism Spectrum Disorder Research. ASHA's comments focused on the need for:

Screeners with high sensitivity and specificity that identify early signs of behavioral,

cognitive, and communication impairments that are critical to accurate and early diagnosis.

Evidence-based comparative effectiveness research that identifies effective treatments.

Research that will provide clear indications regarding which services and support strategies

or combinations are most effective.

Research to assess the efficacy of behavioral treatment approaches to determine which

intervention(s) yield clinically significant improvements in speech, language, and social

communication.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Midterm Project Guidelines and RubricsDocument3 pagesMidterm Project Guidelines and RubricsRenz Gabriel GarduqueNo ratings yet

- Examples of Interference in Daily LifeDocument7 pagesExamples of Interference in Daily LifeDiah Ayu PratiwiNo ratings yet

- 201172-HUAWEI HG655b Home Gateway Quick Start (V100R001 - 01, General, English)Document12 pages201172-HUAWEI HG655b Home Gateway Quick Start (V100R001 - 01, General, English)rgabiNo ratings yet

- TotalSDI Strengths-Based AssessmentsDocument1 pageTotalSDI Strengths-Based AssessmentsostanescusNo ratings yet

- Worksheets PresentationFundamentalsDocument11 pagesWorksheets PresentationFundamentalssandithnavgathiNo ratings yet

- Avaya Communication Manager Survivable SIP Gateway Solution Using The AudioCodes MP-114 in A Centralized Trunking ConfigurationDocument59 pagesAvaya Communication Manager Survivable SIP Gateway Solution Using The AudioCodes MP-114 in A Centralized Trunking ConfigurationCarlos CashortNo ratings yet

- Cumbak Case StudyDocument10 pagesCumbak Case StudyShriyans MalviyaNo ratings yet

- Individual Development Plan 22-23 1Document4 pagesIndividual Development Plan 22-23 1api-549376775No ratings yet

- Popart Printmaking LessonDocument3 pagesPopart Printmaking Lessonapi-242017134No ratings yet

- Netnographic Analysis: Understanding Culture Through Social Media DataDocument16 pagesNetnographic Analysis: Understanding Culture Through Social Media DataShweta AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Research DocumentDocument11 pagesResearch Documentapi-321028992No ratings yet

- 11.2.1 Packet Tracer - Configure and Verify eBGP - ILM TraducidoDocument4 pages11.2.1 Packet Tracer - Configure and Verify eBGP - ILM TraducidoCrisgamerGDNo ratings yet

- Friendship With Foreigners - A2+Document4 pagesFriendship With Foreigners - A2+Юліана РевенкоNo ratings yet

- Newspaper Report WorksheetDocument13 pagesNewspaper Report WorksheetIdam SupianaNo ratings yet

- DLL Perdev 2Document6 pagesDLL Perdev 2Precious Del mundo100% (1)

- Graph 120 Ol - Fall 2018 - Greg KammerDocument4 pagesGraph 120 Ol - Fall 2018 - Greg Kammerdocs4me_nowNo ratings yet

- NFC Digital Protocol Technical SpecificationDocument194 pagesNFC Digital Protocol Technical Specificationtomathivanan100% (1)

- ED123 - Unit 3 - Lesson 3 1Document9 pagesED123 - Unit 3 - Lesson 3 1James Arnold TapiaNo ratings yet

- Formulir Astra 1st 2012Document7 pagesFormulir Astra 1st 2012Annisa Rahayu PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Efficient mobile cloud computing communicationDocument1 pageEfficient mobile cloud computing communicationRamu gNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 TestDocument11 pagesGrade 8 TestMichael Manipon SegundoNo ratings yet

- Communication StrategyDocument21 pagesCommunication Strategydanica dimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Company Profile CV - Wakatobi Indonesia - EmailDocument26 pagesCompany Profile CV - Wakatobi Indonesia - EmailMohamad RopikNo ratings yet

- Social Media Use and Preferences of Bahir Dar University StudentsDocument43 pagesSocial Media Use and Preferences of Bahir Dar University Studentsmubarek oumerNo ratings yet

- Research Analysis CoGameDocument31 pagesResearch Analysis CoGamesarok8No ratings yet

- 9 MnemonicsDocument2 pages9 Mnemonicsapi-396767767No ratings yet

- Software Is A Set of InstructionsDocument6 pagesSoftware Is A Set of InstructionsAbdul RafayNo ratings yet

- Empowerment Technologie S: Prepared By: Paul Jerome S. RicablancaDocument71 pagesEmpowerment Technologie S: Prepared By: Paul Jerome S. RicablancaJhon Juvan EdezaNo ratings yet

- LKS Ujian Praktek B. Inggris 2018Document3 pagesLKS Ujian Praktek B. Inggris 2018yulianaNo ratings yet

- Eg8145v5 DatasheetDocument4 pagesEg8145v5 DatasheetGabriel BenalcázarNo ratings yet