Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why We Draw

Uploaded by

AndrewBadleyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Why We Draw

Uploaded by

AndrewBadleyCopyright:

Available Formats

DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY

Why We Draw.

A critical analysis of why we draw as architects.

Andrew Badley BA(Hons)

5/21/2014

MArch 5013: Comprehensive Dissertation

Tutor: Ben Cowd

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of De Montfort University for

the degree of MArch Architecture. May 2014. Leicester School of Architecture

1

Statement of Originality:

I confirm that I am the sole author of the text submitted for this dissertation, and

that all quotations, summaries or extracts from published sources have been

correctly referenced. I confirm that this dissertation, in whole or in part, has not

been previously submitted for any other award at this or any other institution.

Signature:

Full name (printed):

Date submitted: 02/05/2012

Final Turnitin rating:

2

0.1 Abstract

This thesis is an exploration of architectural drawing today; it began under a presumption that for the

reasons of BIM and nature of the profession itself that the architectural drawing was at risk. The need for

Symposiums such as Is Drawing Dead? at Yale School of Architecture and research from the RIBA in 2009

entitled The Drawing is Dead Long Live Modelling by Keith Snook suggested that the drawing could

potentially be dying.

Taking a phenomenological approach to architectural drawing this thesis attempts to answer why we

draw and define a purpose for the architectural drawing.

3

0.2 Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my tutor Ben Cowd for his time and expertise through tutorials during this study.

Conversations with Ben have clearly shaped the direction of this thesis. Also to Dr John Ebohon, his lecture

series has provided me with much knowledge and entertainment over the course of this thesis.

I must also thank my dad for his continual support and reading this thesis through so many times.

Finally I must give thanks to all other members of staff and fellow students whom I have discussed this

topic with throughout the year.

4

0.3 Table of Figures

Figure 1, Cover of AD: Drawing Architecture.

Figure 2.Design for the Villa Pisani at Bagnolo, Andrea Palladio (c.1542)

Figure 3. Baldassare Peruzzi's drawing of St. Peter's Basilica

Figure 4. Leonardo Da Vincis anatomical drawing of the skull, (c.1489)

Figure 5. Frank Gehry, Preliminary sketch for the Walt Disney Concert Hall

Figure 6. Typical building construction drawing.

Figure 7. The Future of Drawing? Post graduate work, A Defensive Architecture by Nicholas Szczepaniak

Figure 8. A print screen of the website www.pinterest.com . This page continues in a similar vein for hundreds of images.

Figure 9. A closer image of one of the search results in Figure 7. Notice how little information is provided with the image.

Figure 10. Image of the Tower of living energy CRAB Studios (2010)

Figure 11. Image of the Tower of living energy CRAB Studios (2010)

Figure 12. Initial Venn Diagram of Drawing Categories, Andrew Badley (2014)

Figure 13. Peter Cook, The Plug-In City (1964)

Figure 14. Peter Cook, The Plug-In City (1964)

Figure 15. Peter Cook, The Plug-In City (1964)

Figure 16. Le Corbusiers drawings for mass production artisan dwelling from his Towards a New Architecture (1924)

Figure 17. Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, Centre Georges Pompidou (1977)

Figure 18. Giovanni Battista Piranesi , Carceri Plate VI - The Smoking Fire (1761)

Figure 19. Lebbeus Woods, Photon Kite, from the series Centricity, 1988.

Figure 20. Lebbeus Woods, Radical Reconstruction, 1997

Figure 21. Lebbeus Woods, San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City, 1995.

Figure 22. Peter Cook, Diploma Project (Unknown)

Figure 23. Zaha Hadid, Diploma Project Malevichs Tektonik (1977)

Figure 24. Pascal Bronner, New Malacovia. (2009)

Figure 25. Pascal Bronner, New Malacovia. (2009)

Figure 26. Tom Noonan, The Reforestation of the Thames Estuary (2010)

Figure 27. Tom Noonan, The Reforestation of the Thames Estuary (2010)

Figure 28. Zaha Hadid, The Peak Drawing(1982)

Figure 29. Zaha Hadid, The Peak Drawing (1982)

Figure 30. Zaha Hadid, Vitra Fire Station Drawing. (1990)

Figure 31. Zaha Hadid, Vitra Fire Station (1994)

5

Contents

0.1 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................................... 2

0.2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................... 3

0.3 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 4

1.0 Setting The Scene ...................................................................................................................................... 7

2.0 Literature Review ...................................................................................................................................... 8

2.1 Architectural Drawing in the Beginning ................................................................................................. 8

2.2 Defining Architectural Drawing ........................................................................................................... 14

2.3 Grasping for the Fifth Dimension: Reviewing the Literature ............................................................... 16

Going Beyond the Line: A Phenomenological Approach to Architectural Drawing .............................. 18

Peter Cook, Drawing: The Motive Force of Architecture ...................................................................... 23

3.0 Context: Why do we Draw? ..................................................................................................................... 27

3.1 Methodology: Ontology & Epistemology ............................................................................................ 27

3.2 Case Studies ......................................................................................................................................... 27

Communicating the ideal ...................................................................................................................... 28

Dreamers ............................................................................................................................................... 28

Seduction ............................................................................................................................................... 28

Draw to Design ...................................................................................................................................... 29

Why Do We Draw? Continued ................................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

Communicating the Ideal: Peter Cook & Archigram (1960-1975) ......................................................... 29

Drawing to Dream: Piranesi (1720-1778)/ Lebbeus (1940-2012) .......................................................... 34

Drawing to Seduce: Student Work ........................................................................................................ 38

Drawing to Design: Early Zaha Hadid (1976-1994) ................................................................................ 42

4.0 Conclusions: Why Do We Draw? ............................................................................................................. 46

5.0 Bibliography ............................................................................................................................................. 48

6

Figure 1, Cover of AD: Drawing

Architecture.

7

1.0 Setting The Scene

My journey began by exploring the field of architectural representation, quickly discovering that it is a rich

picking ground for fresh ideas on how best to represent architectural ideas. Each individual medium has its

merits, showcasing architecture in a different light with different qualities; film is a fluid medium

incorporating both vision and sound, drawing a static and precise image carefully constructing meaning

within its lines and shade and modelling able to show a proposal at various scales highlighting various

different issues with a project. It is drawing which I have decided to hone in on, analyse and criticise

An initial reading of AD: Drawing Architecture, see figure 1, which if you like has inspired me to investigate

this topic further for myself, suggests that architects should strive to add an additional dimension to their

drawing. Implying that a drawing has the potential to convey feelings and emotions or at the very least

give an additional experience above and beyond what would be considered conventional within

architectural drawing today. The issue looks at architectural drawing from a largely phenomenological

perspective, through which you experience the drawing and are able to extract a subliminal meaning,

potentially making the drawing a much more useful tool for the architect.

The field of architectural drawing itself is both broad and complex with the term drawing being

extremely vague within the digital context of today. This has given rise to a wealth of methods and

techniques that are utilised to communicate architectural form, ideals and aspirations. Focussing and

examining even a small section of this would consist of more than enough questions that are yet to be

answered. Prior to a question being decided upon it would be correct to review the field within its wider

context then perhaps narrowing down further to a more precise remit within which to work.

Upon further reading it became apparent that there was consensus that architectural drawing was at risk.

The need for Symposiums such as Is Drawing Dead? at Yale School of Architecture and research from the

RIBA in 2009 entitled The Drawing is Dead Long Live Modelling by Keith Snook suggested that the

drawing could potentially be dying. With drawing being such an integral part of the profession till now this

was puzzling and an issue which clearly required further investigation. We begin by looking at a brief

history of the humble drawing, going back to its roots, and then through to the present day. How was it

born? Who has attempted to push the architectural drawing above and beyond its place at different

moments in time?

8

2.0 Literature Review

2.1 Architectural Drawing in the Beginning

Plato

Plato speaks of two kinds of simulacra (image making), which creates a thought-provoking context where

a discussion about architectural image can take place. The first is a faithful representation, attempting to

precisely copy the original. This relates to the plans, sections, elevations and their associated non-illusory

drawings. The second image type is distorted intentionally in such a way to make it appear correct to its

viewers. This second type of image is embodied by the more romantic perspective image; used to better

communicate the qualities of light, space and material of a space making them more susceptible to this

distortion. It is of no surprise to me that images of this nature could acquire a reputation for not being

wholly honest, comparative to the technical and precise orthogonal drawings. Perspective imagery seems

to have a tendency to omit or include details to further the impact of the idea which they intend to

portray

1

. These two types of simulacra is an issue that will need to be highlighted and addressed, but first I

must look further in to the history of architectural drawing, describe the origin of a drawing standard

which has not changed much over the previous five centuries, highlight those who pushed its boundaries

or attempted to question the paradigm in architectural drawing.

The Birth of the Drawing

The beginnings of the formal architectural drawing can be accredited to Giotto (1266-1337), even though

it was ultimately refined and popularised by Alberti (1404-1472) and his contemporaries, giving the

architectural drawing its high place in the architectural profession. Previously the architect would

communicate his vision through carved models

2

, drawings used were full scale mock-ups of details to be

carved by stone masons etc. They were used as more of a tool in their own right, to carve and shape the

stone accurately, rather than to communicate a complete architectural endeavour. The position of the

planar architectural drawing was strengthened further when Raphael (1483-1520) inherited the task of

completing St Peters Basilica, Rome, from Bramante (1444-1514) due to ill health in 1513. Work had

begun, yet there was no clear set of drawings which laid out Bramantes complete vision for the Basilica.

In a letter to the Pope Raphael expressed strongly that architectural drawings should consist of the plan,

the section and the elevation. Previous methods had proved inadequate, something needed to change.

Following this drawings were produced of the new design and upon Raphaels death in 1520, St Peters

was completed by Antonio da Sangallo the younger (1485-1546) using the drawings of Raphaels vision.

Finally Palladio (1508-1580) then cemented the place of the orthogonal architectural drawing as a

professional standard with his four books of architecture, which found many imitators, see figure 2.

1

(Powell & Leatherbarrow, 1983, p. 53)

2

(Carpo, 2013)

9

Figure 2.Design for the Villa

Pisani at Bagnolo

Andrea Palladio (c.1542)

10

The architectural drawing had become indispensable in the realisation of an architectural building, taking

the form from the mind of the architect into our reality through a series of unambiguous, precise

drawings. Over approximately one hundred years we see the birth of the drawing and its development

into an essential part of the profession. This move by Alberti, and his contemporaries that followed,

changed the role of the architect from a maker of buildings to a maker of drawings. Previously an

architect, or master builder, would have been on site directing the work as he saw fit from the design in

his mind. Since the architect remains the conceiver of the idea, but uses the drawing as a medium through

which they communicate their design.

Drawing in this way was born, as I see it, out of Albertis desire to communicate his ideal of the true

measure of a building. The planar orthogonal drawing proved the perfect tool, its language not distorted

by perspective, communicating precisely the principles of Vitruvian proportion so important to Alberti.

Following this birth through desire, the plan, section and elevation was then realised fully as a method to

communicate an idea unambiguously. The act of drawing a building precisely in a combination of plan

section and elevation is the point at which an idea leaves the mind of the designer and becomes

something physical, something buildable by someone other than its conceiver. Once it is drawn in these

planes it becomes unambiguous, no longer open to interpretation, it is in its self a complete idea. This is

an issue I will explore further at later point in this thesis.

This is not to say that this paradigm of architectural drawing was not challenged both during and since its

establishment. In the renaissance during its rise and other points in the history of drawing there have

been those who pushed its boundaries and played with its conventions. Around the time of the formation

of these standards within architectural drawing it was creative minds such as Giuliano da Sangallo (1445-

1516) and Baldassare Peruzzi (1481-1536) that were providing a counterpoint to the orthogonal drawing

as it began to grab hold of the profession. Both were experimenting with alternate methods of

representing building through drawing, whilst inevitably practicing orthogonal techniques.

Ideas seen beginning to surface in the work of Peruzzi and Sangallo include the passage of time, qualities

of light and the movement through space.

3

These characteristic are most evident in the work of Peruzzis

work. Peruzzi was an accomplished architect painter and scenographer. He was a master of both the

perspective and orthogonal drawing, these skills can be seen in his highly accurate orthogonal section of

the Pantheon in Rome and in his perspective as part of his scenography work. Therefore we can assume

that as Peruzzi bends and breaks and experiments with the rules it is clear he is searching for something

that neither perspective nor orthogonal drawing expresses individually, it is an attempt to create new

drawings beyond orthogonal (plan, elevation and section) and the perspective.

3

(Brothers, 2012)

11

This experimentation/ ingenuity can be seen in Peruzzis representation of his own design for St. Peters

Basilica, which mimics the qualities of anatomical drawing.

4

Anatomical drawings could allow us to

speculate the reasoning behind Peruzzis choice. Drawings in anatomy are not bound by the same

pressures and constrains of an architectural drawing. They serve only as a means through which to

understand the body. Through this we can read that Peruzzis drawing of St. Peters Basilica to be fulfilling

the same role. The drawing is highly complex combining perspective view sitting atop a plan. This drawing

shows:

1. The conception of the building, in the plan.

2. The construction of the building, the half built piers.

3. The completed building, at the back.

The drawing suggesting temporal ideas of the design in different stages of construction, combining ideas

that the plan or the perspective would struggle to communicate as well in isolation. This drawing shows an

innovative way to represent the space using the axonometric view, which in itself an impossible view and

an abstraction of space. The fact that Peruzzi was a painter and scenographer is reflected clearly in his

choice of representation, Peruzzi much more concerned with the qualities of inhabited space than the

quantifiable co-ordinates of Cartesian space.

5

However, these drawing efforts were not imitated like the orthogonal drawings Palladio. Perhaps due to a

lesser need for the qualities which they attempted to better express? Maybe it was because there simply

was not a clearly defined need for drawings of this type? Whatever it was these drawing seem to fade into

the background, used occasionally when an architect felt like displaying a little bit of flair. So the history of

architectural drawing continues, after the diversity of Peruzzi and Sangallo, along the path of the

orthogonal drawing with its clear purpose supplemented by the perspective view.

Drawing the ideal

It is clear from Architectural drawing in practice today that it has remained much the same since its

conception. Arguably the most influential change on drawing, at least for those who draw to build, was

the promotion of the architectural drawing to a contract document in the nineteenth century. With this

additional legal weight on the drawing it is reinforced as a communicative tool to build resulting in a

growing profusion of working drawings.

6

This is opposed to a drawing that explicitly expresses

architectural ideas. As a result, from this point this history will focus on those who had something to say

and explicitly communicated it through drawing, rather than those who draw to build. Comparisons will

never the less have to be made between the two, this will ground the ideas of those constructing in the

reality of the paper in the reality we all share.

4

(Brothers, 2012)

5

(Powell & Leatherbarrow, 1983, p. 19)

6

(Powell & Leatherbarrow, 1983, p. 50)

12

Figure 3. Baldassare

Peruzzi's drawing of St.

Peter's Basilica

Figure 4. Leonardo Da

Vincis anatomical

drawing of the skull,

(c.1489)

13

Conclusion

The stagnant nature of the field of architectural drawing, within the vast majority of the building

profession, has left architectural drawing as just a contract drawing; it is unambiguous and lifeless. Now

that the digital is almost ubiquitous within the profession, the seamless production of these lifeless

contract drawings is becoming a reality. This is through the development of software such as Revit,

competing with the traditional drawing method, encouraging the use of the 3D, from which contract

drawings would be generated by the software. If this were true it would release architectural drawing

from constrains over five centuries old. Freed from these constrains, what would architectural drawing

become? How would it evolve? Are the answers found in visionaries who have fallen by the wayside? Or in

the contemporary critics and champions of architectural drawing today?

Cammy Brothers presents an alternate history of architectural drawing

7

, which proceeds on the basis that

the functional elements of architectural drawing are relaxed. It is pointed out the since the conception of

the plan section and elevation architectural drawing in the 15

th

century, many of the qualities architectural

drawing have changed very little. Brothers drawn upon a comparison with the world of contemporary art,

which by contrast has seen its techniques, subject matter etc. progress and change drastically over the

same time period.

Brothers outlines a potential alternate history of the architectural drawing, suggesting that it was at the

margins of the 15

th

and 16

th

century, whilst the conventions were being formed that the future of the

drawing lies

8

. Rather than focussing on the conventional history of drawing, Brothers looks for

alternatives. Citing the work of Sangallo and Peruzzi, discussed earlier, who were challenging the drawing

conventions before they were set. She suggest with the art of drawing seemingly at risk it needs to find a

new niche, that its in the aspirations of creative such as Peruzzi and Sangallo, aspirations still not fully

satisfied today, that the future of the drawing lies. The question begs, what would this niche be? And what

is drawings purpose? Essentially, why do we draw?

7

(Brothers, 2012)

8

(Brothers, 2012)

14

2.2 Defining Architectural Drawing

Drawing could mean so many different techniques and types of drawings which themselves have many

different uses. This section aims to define the specific area of drawing this thesis will be directing its

attention towards.

Beginning with the sketch; a versatile rapid technique which can be used to understand, to explain or as a

form of notation. It is a very personal form of drawing integral to an individual architect and could aid in

helping to define them. This can be seen in the work of Louis Kahn as his sketching style developed during

his trips abroad to the ancient world so too did his architectural style. Kahn once said he was

intellectually, emotionally and physically interacting with the sketch. Immersed in the making, he had

rubbed out, crossed out and drawn over many aspects of the sketch as if it spoke to him

9

One must hold

the opinion that the sketch is not and will never be at risk. This is a technique unlike any other integral to

the architects design process, the part of the role of an architect which will never change.

Next, the construction drawing; this has; as we have seen, risen to prominence following the introduction

of the plan, section and elevation. This is a drawing which varies from architect to architect but uses what

is fundamentally the same language. The construction drawing has evolved out of the orthogonal drawing

introduced as means of communicating the true measure of a building, its humanist qualities otherwise

distorted by the perspective in the real world, it has become the drawing which instead much like the

sketch is a tool.

So where does that leave the architectural drawing? If BIM is to free the architect from the production of

the construction drawing, what does the architectural drawing become? We know from today that often

drawings are the only pieces left which show what a building was once like or what it could have been,

whether it was demolished, never reached construction or were never intended to be built. Thus the

architectural drawing provides us with the means of understanding the architecture its self. This is an

issue that need exploring further.

So to conclude the sketch is a design tool used by the architect to resolve, understand and develop a

proposal or its constituent parts. The construction drawing is a tool used to communicate the means of

construction. The architectural drawing then communicates the architecture or architectural idea,

whatever that may be. In this away the architectural drawings becomes about a want to communicate

your design ideas to a wider public. The drawing becomes more aligned with Platos second form of

Simulacra, an image distorted intentionally in such a way to make it appear correct to its viewers, so the

viewer can see the idea, much more about the ideal than a Cartesian representation of reality; an art not a

technical exercise.

9

(Kahn, 1991)

15

Figure 6. Typical

building construction

drawing.

Figure 5. Frank Gehry

Preliminary sketch for the

Walt Disney Concert Hall

Figure 7. The Future of

Drawing? Post graduate

work, A Defensive

Architecture by

Nicholas Szczepaniak

16

2.3 Grasping for the Fifth Dimension: Reviewing the Literature

In beginning a review of selected literature we start where the ideas of this thesis were planted and began

to grow, the issue of AD: Drawing Architecture. Upon flicking through the issue you immediately notice a

vibrant array of different image which utilise a plethora of techniques digital, hand and a combination of

the two. If unaware of the contents then you would be forgiven of thinking some of the images were

contemporary art, maybe architectural drawing is finally catching up? (This is parallel has been drawn

previously by Cammy Brothers.) At the very least it shows architectural drawing is by no means dead.

Although this architectural drawing is not dead it seems to be confined to

10

:

Experimental Practices (Will Alsop, Narinder Sagoo/ Foster and Partners, Morphosis)

Visionaries, whose projects are not necessarily intended to be built, the project lives through the

drawing, able to provoke a response from the architectural profession. (Archigram, Russian

Paper Architects, Neil Spiller)

Students, who find themselves in a similar position to a visionary in that their project is highly

unlikely to be built and again are producing drawings to communicate an architectural ideal.

The issue is guest edited by Neil Spiller, mentioned previously. In his introduction Architectural Drawing:

Grasping for the Fifth Dimension he highlights three key points that need addressing, these are

supplementary to the main thrust of the piece which suggests that there is an additional dimension

beyond the four dimensions (three spatial and time) that architects are aspiring to when producing these

architectural drawings.

1. Architectural Drawing has benefited from the digital revolution.

2. A good scheme and/or drawing must allow for speculative re-reading.

3. The notion of Donegality.

Firstly, architectural drawing has benefited from the digital age. Spiller says that while one might have

expected the computer to have fully exceed hand techniques Spiller suggest that paradoxically the

opposite is true.

11

Spiller supplements this with this thought, Todays architects have a wealth of

techniques processes and approaches with which to make their architecture. It is a consistent

disappointment to me that more architects do not explore the wilder and more beautiful terrains of our

discipline. Why are so many of us happy to revert to a tired and defunct modernist doctrine?

12

If the

word architecture is replaced with architectural drawing then the statement still stands, as architectural

drawing is an integral part of architecture, the first act of building (for architects at least) is drawing. This

seems to be largely true; the digital revolution has only contributed new techniques and methods of

10

(Spiller, Architectural Drawing: Grasping for the Fifth Dimension, 2013, p. 6)

11

(Spiller, Architectural Drawing: Grasping for the Fifth Dimension, 2013, p. 14)

12

(Spiller, Architectural Drawing: Grasping for the Fifth Dimension, 2013, p. 17)

17

drawing, not taken away. As for architects who choose to revert to a the modernist doctrine of clean line

drawings, even though one might argue that it does not represent their architectural ideals then the

question again needs to be asked Why are they drawing?

Included below is a brief first person account of the authors experience with the digital:

For myself born in 1991 I have for the most part grown up with computers and advances in

technology; it is a fully integrated part of my life. It is clear compared to many people, typically

older but also includes people around my age who are not as familiar with the computer, I find

programs on computer intuitive to use; easily navigating shortcuts and connections between tasks

and intuitively know how they could work together. It feels like this comes easier to me, which I

believe arises from an integral understanding of the computer that is embedded within me. Many

believe the argument and distinction between analogue and digital is tired and now

inappropriate. This is a sentiment, in terms of quality and image production, that I would agree

with. However the impact of the digital age on how images are perceived generally in this

information age could prove useful in the conversation about Why We draw?

Second the idea that A good scheme and drawing must have enigmas, a certain elbow room for

speculative re reading.

13

The way in which an architectural drawing is read and re read is an interesting

thought to consider, how an architectural drawing needs to have a certain amount of ambiguity in order

to be successful. Let me make it clear that this is by no means suggesting that planning drawings or the

like should be ambiguous, far from it; this only applies to drawings used to communicate ideas about

architecture. Perhaps the answer to this lies in Spillers next point.

Finally, donegality is a notion which Spiller raises with respect to architectural drawing. The word

donegality was introduced by Michael Ward in his book Planet Narnia. Spiller sees it as a potential route

to discovering what this fifth dimension may entail. Donegality is defined as:

By Donegality we mean to denote the spiritual essence or quiddity of a work of art as intended by the

artist and inhabited unconsciously by the reader. The donegality of a story is its peculiar and deliberated

atmosphere or quality. that the author consciously sought to conjure, but which was designed to remain

implicit.

14

Spiller urges readers to consider the donegality of each drawing as they continue through the issue, see

what would otherwise be inhabited subconsciously. It suggests that each individual reads each

architectural drawing differently, in a way that is subconscious but also subjective. This would fit into the

concept that a good drawing allows for speculative re-reading, how ideas would change as you gain new

thoughts and knowledge between subconscious re readings of the ideas presented in a drawing, this is

alongside those which are created sub consciously by the mind.

13

(Spiller, Architectural Drawing: Grasping for the Fifth Dimension, 2013, p. 7)

14

(Ward, 2008)

18

All the issues raised point towards phenomenological approach to drawing in architecture, an aspect the

author was keen to explore in this thesis. Too many architects revert to modernist methods to represent

their work using defunct modernist doctrines why? Is it because it is easier? Is it because clients read

them better? Is it because they are the drawings needed for planning approval? Is a financial pressure on

the office?

As a result of these ideas, my reading now focuses on the work of phenomenologists such as Juhani

Pallasma, Dalibor Vessely and Martin Heidigger; supplemented by the thoughts Peter Cook, a prominent

thinker on architectural drawing. Borrowing the ideas of these authors the text will assess each of the key

ideas highlighted from Spillers introduction in the hope that a thoughtful discussion upon the donegality

of architectural drawing arises.

Going Beyond the Line: A Phenomenological Approach to Architectural Drawing

Juhani Pallasmaa has a phenomenological approach to architecture, he concerns himself with the essence

of architecture and has researched and written widely on the subject including The Eyes of the Skin:

Architecture and the Senses, The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom and he was also a

speaker at the Is Drawing Dead? symposium at Yale School of Architecture. So as you would imagine in

his book The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture Pallasmaa talks about the image

of architecture in the poetic sense, its essence, and how these images are embodied and experienced by

an observer; ideas already beginning to draw parallels to those introduced by Spiller.

The Digital Age and the Image

As previously mentioned analysing the aesthetic qualities of architectural drawing as a result of the digital

revolution is not something which this thesis wishes to concern its self with, the aesthetics of drawing are

far too subjective and dependant on what and why it is being drawn. Pallasmaa addresses this in his first

chapter Image in Contemporary Culture he speaks of the negative impact of the current Hegemony of

the image

15

. Citing that prior to the age of mass literacy humans primarily communicated through the

use of images and gesture, Pallasmaa even goes so far as to suggest that we could be returning to a new

illiterate age.

This hegemony of the image is no more apparent than on the internet with sites such Pinterest, Instagram

and Tumblr, see figures 7 and 8. After typing your search criteria in you are bombarded with images which

are offered with no/the bare minimum of additional information. Pallasmaa talks about how this excessive

flow of imagery, caused by advances in technology and communications is leading to a fragmented view of

15

(Pallasma, The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer),

2001, p. 15)

19

Figure 9. A closer image

of one of the search

results in Figure 7.

Notice how little

information is provided

with the image.

Figure 8. A print screen

of the website

www.pinterest.com .

This page continues in a

similar vein for

hundreds of images.

20

the world. By comparison the information in a book is embedded within a causal narrative which gives

depth to the knowledge. Compare this to images on Pinterest where images are presented, initially, with

almost no narrative or additional knowledge to supplement or ground the image.

This makes the image a detached and fragmented piece of knowledge

16

, what Pallasmaa calls

fragmented knowledge. This could be looked at from two different perspectives; the first is, as the

draughtsmen of an architectural image how do you make your drawing stand out? How do you seduce

someone? Or is it that this kind of image searching is purely aesthetic and devalues a drawing, by

removing information that places it in context and allows it to speak fully?

The Re-Reading of the Drawing

In his second chapter Language Thought and Image Pallasmaa raises points of interest with regards to

Spillers second point A good scheme and/or drawing must allow for speculative re-reading. Upon reading

this chapter with the awareness of Spillers comments interesting ideas arise from the notion that a good

drawing needs sufficient elbow room for this speculative re reading, and provides potential explanations

as to why this is the case.

Pallasmaa begins the chapter by comparing the creator of the embodied image to a literary author. How

an author uses their words to construct their reality in our minds, a good book places us in that reality.

Elaine Scarry in her book Dreaming by the Book asks By what miracle is a writer able to incite us to bring

forth mental images that resemble in their quality not our own daydreaming but our own [] perceptual

acts

17

When writing a book it is impossible to include every single detail, therefore leaving much up to

the mind of the reader to complete the reality they are to inhabit while reading the book. However, it is

clear that each reader will interpret the authors description differently.

Scarry believes that the great authors have learned to mimic the way in which the brain perceived the

world within their writing

18

. The core ideas, what could be described as anchors of the reality, of the scene

will remain constant but the ambiguities in the description will vary. This is realised when a book is

translated to the screen, immediately these places read about are more complete, the ambiguities

reduced significantly, filled with the directors interpretation of the authors description. You see how they

have embodied the text and made the story their own; perhaps this is why many feel films never quite live

up to the book that they read?

It could be suggested that for architects our native language is drawing, sketches are often used to

communicate ideas in a quick and efficient manner, I have experienced this both in practice and

education. Would it benefit the architectural drawing in certain circumstances to have this ambiguity

16

(Pallasma, The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer),

2001, p. 15)

17

(Scarry, 2001)

18

(Pallasma, The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer),

2001, p. 29)

21

incompleteness to it, to encourage this kind of embodiment? Pallasmaa goes on further to suggest that

this incompleteness may prove more stimulating for a viewer, allowing for easier embodiment of the

image. Pallasmaa cites the work of prominent neurologist Semir Zeki.

Incompleteness and ambiguity of the artistic image activate our minds and maintain an active attention

and interest. Semir Zeki points out that artistic ambiguity is not vagueness or uncertainty in the usual sense

of these words, but on the contrary, certainty the certainty of many different, and essential, conditions,

each of which is equal to the others, all expressed in a single profound painting, profound because it is so

faithfully representative of so much.

19

This when applied to the architectural image in the sense that we discussing here, suggest that in order for

an image to be embodied, and have a maintained embodiment, the image itself needs to have enough in

it which is recognisable and familiar to the viewer in order for the authors aim to be grounded. Whether

these be physical objects in the drawing that are recognisable from our own reality, or the language of the

drawing has certain cues which allow the user to generate enough of mental image from their mind to be

activated. Once activated the interest of the observer is then held as they themselves take control of the

idea; they embody the drawing becoming part of the idea itself. They see things in a different way to the

author; the idea in a sense becomes theirs.

It is this same ambiguity in a drawing that makes the rereading of drawings so important. In Dalibor

Vesleys book Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation: The Question of Creativity in the Shadow

of Production Vesley talks about the Greek phenomena of mimsis. In a traditional approach (non-digital)

to architectural design the architect would use skill, knowledge and imitation to derive a finished

building.

20

This knowledge can only derive from past lived experiences and memories of the designer;

21

as

such a certain element of mimicry occurs. The Greeks call this imitation through chance mimsis. If this is

true, then as our experience of the world grows so will our knowledge and thus the nature of our mimsis

will change.

This would suggest if a drawing is read in a certain time and place its ambiguities will be filled by a certain

element of mimsis, then as time passes and our experience of the world grows our mimsis will change

and thus the embodiment of the drawing. This could potentially lead to new ideas being created around

the same drawing simply through a rereading. Although because it is a re-reading, the observer will

already have the past experience or knowledge of the initial reading; over a short period of time it is

unlikely much will have changed. This phenomenon of re-reading becomes much more apparent when

taken over a longer period of time.

19

(Pallasma, The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer),

2001, p. 30)

20

(Vesely, 2006, p. 287)

21

(Vesely, 2006)

22

Donegality

Finally to the notion of donegality in architectural drawing which ties in with a phenomenological

approach to the drawing, ideas of poetics and a fifth dimension. Donegality is described as the essence or

poetics applied by the author of the image. Again Pallasmaa addresses ideas surrounding this in his book,

allowing for expansion and exploration into this notion of donegality.

Again using the idea that much that is applicable to architecture should also be applicable to the way in

which it is drawn, phenomenologist Adam Sharr suggests in his book Heidegger for Architects that: When

thinking about architecture from a humanistic point of view, the importance must be placed on the

inhabitation and experience of the place of the priorities of aesthetics.

22

Why should this not be a

consideration in our architectural drawings? Would the architectural idea not have a much better chance

of succeeding or being received well if inhabited and experienced by the viewer? Perhaps it is this

donegality, whatever form it may take that allows for this inhabitation; the essence left by the author

after finishing the drawing providing the spark/ tone for this inhabitation.

Pallasmaa says The most deeply existentially and experientially rooted architectural experiences impact

our minds through images which are condensations of distinct architectural essences. Lasting architectural

experiences consist of lived embodied images which have become inseparable parts of our lives.

23

This is

based upon a theory that the way in which we think and communicate our thoughts and ideas is

neurologically image based, rather than linguistic. It suggests images that we are able to embody and

project onto have a much greater architectural significance as they would become a part of our lived

experience; as suggested in the previous section on re-reading.

So, this inhabitation and embodiment of the drawing becomes key to its success. Pallasmaa describes

artistic images as taking place in two realities and their suggestive power derives from this very tension

between the real and the suggested, the perceived and the imagined.

24

So when a drawing is seen we

inhabit this reality, we touch by seeing. We feel its materials, an experience based upon our knowledge

gained in the flesh of the world. This relates directly back to what has been discussed previously regarding

the ambiguity of the drawing and the need for re reading. This concept of an architectural image having

two aspects, the perceived and the imagined, lends itself kindly to Spillers points if read that the perceived

relates to an images donegality and the imagined relates to the subject of re reading.

The perceived aspect of a drawing is that which is embodied by the artist/ draughtsmens architectural

idea/ ideal. One could suggest that this is the element which grounds the viewers imagination within the

architectural idea being explored, ensuring that the topic does not wander. At the same time this gives the

22

(Sharr, 2007, p. 38)

23

(Pallasma, The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer),

2001, p. 11)

24

(Pallasma, The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer),

2001, p. 63)

23

viewer enough information to allow for a basic construction of this reality, their mind can then begin to fill

the gaps and ambiguities with their own imagination, derived from knowledge gained from their

experience of the world.

The importance of this perceived aspect, becomes apparent in ensuring that there is enough information

sealed within the drawing for the viewer to construct their reality. Pallasmaa says The inability to grasp

the essence of an artistic work usually arises from the viewers incapability to project and experience the

imaginary reality of the work.

25

This inability to experience and architectural drawing would arise from a

lack of an ability to construct a reality in which to embody and experience an ideal, this would reduce the

image merely to its aesthetic qualities. Alternatively this could also mean that the drawing communicates

an essence other than that intended by the author, thus the architectural idea is lost in translation;

eventually having the same outcome as not being able to grasp the essence or donegality of the drawing

to begin with.

Pallasmaa warns of a danger to this kind of drawing saying Todays forceful effort to seek visually

impressive architectural images without concern for other sensory realms may well be the very reason

why these buildings usually appear so mute, rejecting and lifeless, regardless of their unrestricted play of

visual fantasy.

26

This again suggests that over doing the theatrics of the drawing means that the

essence/donegality is lost, the drawing is merely reduced to its aesthetic qualities.

Peter Cook, Drawing: The Motive Force of Architecture

This phenomenological dive into Spillers points suggest that they may have some momentum, before

moving on further it is important to pause to look at the writing and lectures of Sir Peter Cook. Cook gave

his lecture Real is only halfway there at the symposium Is Drawing Dead? and has written broadly on

the subject of architectural drawing; all whilst being one of the biggest visual contributors to the field with

his work as a part of Archigram and since. This analysis will focus on his lecture given at Yale and his book

Drawing: the motive force of architecture.

Real is only halfway there

In his lecture Cook aims to talk about an area of drawing which is very much linked to the discussion of

this thesis. Cook is trying to talk about something which he himself describes as intangible. Perhaps the

donegality of a drawing? Cook defines this intangible element of the drawing as the creative moment

27

the point at which the guts of the architectural idea are shown at their best, most raw and not necessarily

sugar coated or clouded by any aesthetic quality the architect was partial to at the time. In his own words

To me the best drawings have always been those where the preoccupation dominated and the craft

25

(Pallasma, The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer),

2001, p. 63)

26

(Pallasma, The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer),

2001, p. 54)

27

(Cook, "Real Is Only Halfway There", 2012, p. 00:14:00)

24

came, if it was there or if it didnt

28

Suggesting that as long as the core creative moment is embodied in

the drawing then, whether or not the drawing is crafted in an aesthetically appealing way is neither here

nor there.

Cook shows various examples of series of drawings throughout his talk to try and identify where this

moment occurs in a process of drawing, and all follow the same format, an initial sketch, a progressive

drawing of the idea and then a final image. Each time Cook explains how in his opinion the perfect

drawing lies somewhere within the context of the three drawings, but is never achieved by any of them.

The example that struck me most was when Cook takes us through a series of images for one of his own

projects as part of CRAB studio. It is for the Living Energy Project, see figures 10 and 11, a competition

project for a tower in Taiwan. The 3D model had been built and the drawings were to be taken. Cook

shows us three images of the tower and as he flicks between them he talks through the process of

choosing where the image is to be taken from. Cook undulates and stutters as he tries to find the perfect

angle, eventually settling upon figure 10 as the drawing which best shows the creative process. However

the image chosen was in fact figure 11 due to the pressures of life. Perhaps an over desire to seduce? He

describes it as It does have a not completely blue sky, the children are suspiciously happy, the grass is

suspiciously well mown and the concrete is suspiciously smooth. A sense of disinterest or lack of

engagement is detected in his voice, and indeed Cook elaborates by captioning this image picture as he

knows that at this point the moment of creativity it is lost, the guts of the design issue are left behind.

A point which was, one might suppose quite shocking, during this talk was a conversation Cook recalled

having with Dalibor in which Dalibor remarked Buildings dont matter, drawings matter much, much

more.

29

Cook reveals too that he was taken aback by this comment, but one need look no further than

Cooks book Drawing: the motive force of architecture to find reasoning for this. Cook highlights the work

of key contemporary architects who have changed the thinking in architectural discourse through their

drawings, of which he is undoubtedly one. The building does not discriminate between the digital and

analogue reinforcing Cooks view that the preoccupation of an architectural endeavour should be the

main thrust of a drawing not its aesthetics.

Conclusion

This investigation into phenomenology has expanded upon the points made by Spiller in AD: Drawing

Architecture. Pallasmaas phenomenological approach to the image adds flesh to the bones, providing

insight and grounding as to why each of these elements may be important to a successful architectural

drawing. However, there is one question that keeps recurring which is why do we draw?

Cook provides a valuable insight, into the thinking of an author of architectural drawing who himself has

managed to use his reality, created within the bounds of the paper, to affect the reality that we all share

28

(Cook, "Real Is Only Halfway There", 2012, p. 00:28:00)

29

(Cook, "Real Is Only Halfway There", 2012, p. 00:08:00)

25

Figure 10. Image of the

Tower of living energy

CRAB Studios (2010)

Figure 11. Image of the

Tower of living energy

CRAB Studios (2010)

26

(this will be discussed later in the thesis). Cook looks at the work of contemporary architects who also

have achieved the same feat. What is striking to me is the wide range of reasons for drawing. It is not just

about creating a pretty picture, although there is no doubt this at times will help; it is quite clearly about

the idea. This is summed up no better than in his talk Real is only halfway there, where Cook takes us

through the iterations of his image making production as he searches for the image which really

encapsulates the creative moment what he feels is the essence of the idea, if you like has the correct

donegality.

The question of Why do we draw? is a complex question and may not have just one answer, but will

resolve both issues raised so far in this review of the state of the architectural drawing. One, is

architectural drawing dead? This will give the architectural drawing the purpose it needs to survive. Two,

how do we go about representing it? So far it would appear that the architectural drawing is becoming a

more emotionally charged object, leaning towards the world of contemporary art.

Knowing why we draw gives the author a better sense of how to go about achieving it. As such this

question of Why do we draw? - Assuming, as previously stated, that the sketch and construction drawing

are exempt - will be the main thrust of this thesis.

27

3.0 Context: Why do we Draw?

3.1 Methodology: Ontology & Epistemology

On the basis of the literature review this thesis tackles the question of why we draw from a

phenomenological perspective the drawing is seen as emotional and subjective rather than Cartesian,

technical and quantitative view. As such there is something subjective about this fifth dimension Spiller

suggests that architects should strive for through their drawing.

So as one reads this their ontological and epistemological outlooks should reflect this. A postmodern

constructivist ontological outlook is required. The fluid views taken upon reality by those who hold this

approach is key to embodying the ideas presented and expanded upon in this thesis. Ideas of embodiment

being different for each individual view creating an entirely unique reality to them which is both an

embodiment of the drawing and their lived experience. Ideas like this provide the backbone for an analysis

of a series of case studies conducted, each on a specific architect from each camp. As such an empirical

method of acquiring knowledge has also been used, using case studies analysed subjectively.

3.2 Case Studies

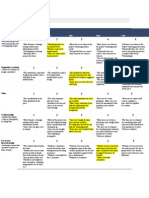

From reading Cook and AD: Drawing Architecture one would suggest that there is no singular answer to

the question why do we draw? As such in this chapter the profession will be broken down into the

predominant categories of why we draw outlining each individual category and then interrogating one of

its protagonists. Although architects will be placed in these categories, these are by no means set in stone.

For it may have been necessary for a drawing to attempt to achieve multiple purposes. This attempt to

characterise and then explore the drawing will begin to answer the question of why we draw from which

others may define new categories and explore those.

To begin this investigation the profession must first be split into their respective categories. One might

suggest from the in investigation so far that the profession be split into four categories. These would be

those who draw to design, those who draw to communicate the idea, those who draw to dream and those

who draw to seduce. Each of these niches which the architectural drawing can be used as a tool for will

now be outlined in brief, before being explored in more depth through a case study.

It should be noted now that it was incredibly difficult to place certain architects in just one category and it

could be argued on architect could fall into multiple camps. This is why architects are duplicated in

different lists.

28

Communicating the ideal

Architectural drawings roots lie in communicating an ideal and architecture itself incorporates many ideas

into the fold of the profession not just form; these could be social, political, economic or technological. All

of these ideas need to be communicated within the context of the project and each other. One could

suggest that the drawing provides the perfect platform for this communication of the idea as a whole.

Why would this tradition of architectural drawing, the language of architects, being used by architects to

communicate their ideals not continue?

Architects and visionaries who one would likely place in this category would be Peter Eisenman, Diller and

Scofidio, Peter Cook/Archigram, Thom Mayne (Morphosis), Foster + Partners, Rem Koolhaas (OMA),

Alberti, Palladio, Stephen Holl, Futurists and Bernard Tschumi.

Dreamers

This category represents those whos reality to build is solely the paper. Their projects are often

speculative work, the reality of the paper is occupied by worlds which are set in the far future or by

architecture of the wildest imagination. The paper often becoming the medium for a pure free expression

of an idea without the constraints of our reality. Even though this is the case many of the projects aim to

address issues which are very prevalent within the present days architectural discourse. Because these

projects are clearly never going to be built the paper is used as a reality in which these ideas can be

constructed, embodied and inhabited. As a result of this these project can then have an impact on the

building profession.

Architects and visionaries who one would likely place in this category would be Piranesi, Lebbeus Woods,

C.J Lim, tienne-Louis Boulle, Brodsky and Utkin (Russian Paper Architects), Felix Robbin , Superstudio,

Peter Cook/Archigram, Hugh Ferris and Neil Spiller.

Seduction

Drawing to seduce is not a new idea, and one would suggest that many people use this as a method to

distract from other elements of the design. However this seduction is an important part of why we draw,

firstly creating beautiful images that are worthy of a work of art is extremely satisfying. More practically

often times when you produce a project that is for a competition or for academic purposes those who are

marking/ judging the work will have very limited time constraints within which to judge. The work may be

on a wall filled with designs, in these situations in order to communicate its ideal your drawing needs to

stand out. It needs to draw in the viewer it needs to seduce them in order for the architectural idea to be

judged it needs to gain their interest and hold it amongst all the other projects.

Architects and visionaries who one would likely place in this category would be Students of the profession,

Snhetta and Thom Mayne (Morphosis). You could also consider many dreamers within this category.

29

Draw to Design

These are architects who use architectural drawing, as the main thrust of their design. Architects who

draw their ideal almost as a piece of art, then the building is produced as close to that work as possible.

This is characteristic particularly of the early work of Zaha Hadid. This concept that architectural drawing

shapes the design rather than vice versa is a new idea in this thesis; so far we have predominantly faced

drawing that has come post design which when compared to this method almost seem an afterthought. If

this category were to become a part of the architectural paradigm then it would shake up the process of

architectural design significantly.

Architects and visionaries who one would likely place in this category would be early Zaha Hadid, Enric

Miralles and Frank Gehry.

In order to better show the crossover between these categories I produced a Venn diagram to visualise

this. This more accurately displays the crossovers, beginning to suggest where combinations of the

purposes of these camps might occur. Although this was only an initial exercise the result can be seen in

figure 12.

Communicating the Ideal: Peter Cook & Archigram (1960-1975)

Archigram was founded in 1960, London. Originally comprised of Peter Cook, Michael Webb and David

Greene; this was then expanded in 1961 to include Warren Chalk, Ron Herron and Dennis Crompton. They

were brought together through a common displeasure with the state of the architectural profession. It

was too unadventurous and respectful, reflective of the world they found themselves in. Peter Cook and

Archigram set about trying to change this through a combination of drawing, modelling and literature.

During their fifteen year collaboration Archigram would create an array of exciting and visually appealing

projects which although never leaving the reality of the paper would significantly help change the

trajectory of the architecture profession and inject it with the optimism and technological progression

which at the time was being seemingly ignored.

We have already seen a snippet of their work Instant City (1968) in a previous chapter and in this study

we will look at perhaps their most influential project the Plug-in City (1964) drawn by Peter Cook. The

project is based around units which can be unplugged and plugged in as required, with their movement

around the city facilitated by a system of cranes mounted at the cities apex. The project is much like that

of what we have characterised as a dreamer would produce, but one must remember Archigram had a

clear idea of what they wanted to change, they were attempting to communicate and ideal and each

member was committed wholly to that purpose.

Cooks drawings can be seen in figures 13-15, these drawing would have been a welcome break from the

modernist drawings of the time, Figure , concerned primarily with the profile drawn through the use of

30

Figure 12. Initial Venn

Diagram of Drawing

Categories, Andrew

Badley (2014)

31

Figure 15. Peter Cook,

The Plug-In City (1964)

Figure 13. Peter Cook,

The Plug-In City (1964)

Figure 14. Peter Cook,

The Plug-In City (1964)

32

Figure 17. Renzo Piano, Richard

Rogers, Centre Georges

Pompidou (1977)

Figure 16. Le Corbusiers drawings for

mass production artisan dwelling from

his Towards a New Architecture

(1924)

33

clean line. They give off a hint of pop art; drawings that would have been pushing the boundaries of

drawing for the period in which they were produced, drawing people into the world of optimism and

technology Archigram aimed to create. Architects in the 60s would have seen this work alongside the

literature of Archigram which would have allowed them to embody the drawings in a way which better

expresses the donegality of Cook in his drawing.

Below is a brief one hundred word account of the authors imagination of the Plug-in City through the

drawing: To me the drawing reads as a complex bustling city, I walk amongst its gigantic web of services,

its once bright colours tarnished and worn. The web is pierced by top heavy high-rise structures; a wealth

of activity is a occurring, framed by the structural web of services. Units of varying sizes are moved by an

automated crane system, the city itself lives, breathes and moves providing a theatrical and ever changing

backdrop to life.

Even now in the twenty-first century the essence of the reality created is one of optimism (at least in my

mind), the idea itself is playful in nature and this is reflected through the drawing, and thus the

embodiment.

The drawing is filled with slight variations upon elements from our reality which everyone could relate to

through their lived experiences, such as the high rise structures and cranes. This is complimented by more

than enough ambiguities meaning the drawing would benefit from repeated rereading to draw new ideas

through re-embodiment. One could also argue that the drawing figure 15 of the Plug-in City is one of the

strongest cases that drawing can directly affect the reality we all live in from the reality of the paper.

This drawing can clearly be seen to have influenced the Pompidou Centre (1977) designed by Richard

Rogers and Renzo Piano seen in figure 17. One would find it almost inconceivable to imagine that this

drawing was not seen and embodied by either Rogers or Piano before or during the design of the

Pompidou Centre. This is a clear case of a project not set in our reality, drawn with the purpose of

communicating the ideals, that has directly affected the way in which architects in our reality design and

build.

By 1975 when Archigram disbanded they had successfully laid the foundations for the high tech

movement with a series of optimistic projects and schemes, drawn in a way which, as Cook would put it,

embodied the creative moment. Cooks drawings are by no means the suspiciously complete drawing

that, without interest, he describes in his lecture. They are full of life and intrigue, drawing architects in

and holding their interests through the possibilities of ambiguity. As a result the influence of Archigram

and Cook is clearly visible in the early work of the high tech movement and is acknowledged in the later

writing of architects such as Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid.

30

30

(Design Museum, 2007)

34

Communicating the ideal: Conclusion

Peter Cook and Archigram are living proof that by the means of simply drawing an idea an architect can

influence the profession. Building is no longer necessary in this respect. But communicating an ideal

comes in all scales and sizes, it could be social and technological like those of Archigram, or could be as

simple as describing the geometric concept of a small house and how this relates to its context.

One would suggest that drawing is the best way to communicate this, drawing is after all the language of

the architect and with prominent neurologist like Semir Zeki, suggesting the mind thinks through

neurological images, it may even prove scientifically more beneficial. Whatever the case the drawing will

have a better chance of success, it would seem, if it embodies the idea of the creative moment. Again

grounding itself in our reality through familiarities the design will have a better chance of being embodied

and, much like the work of dreamers, re reading will allow for the idea to grow and change as people gain

knowledge and experience of the world; making many of these drawing, such as those by Archigram, just

as applicable today as they were shortly after their conception. In a sense the drawing has a life of its own.

Drawing to Dream: Piranesi (1720-1778)/ Lebbeus (1940-2012)

Architectural drawing since the adoption of the planar drawing remained practically unchanged for two

centuries. It appears that there was a craving amongst some to communicate more through the drawing,

opposed to simply form and the true measure of a building. We see from the work of draughtsmen such

as Antoine le Pautre (1621- 1679) and his contemporaries a desire to communicate the experience of

space, a quality displayed by Peruzzi and Sangallo before them.

The next major stimulant of the field arrived in the form of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778). Piranesi

was an etcher, archaeologist, architect and a dreamer. He left for Rome in 1740 in search of architectural

work; instead he found work as a vedutisti.

31

This involved producing etchings for the inclusion in

guidebooks and to sell to tourists. In this work Piranesi was free from the constraints of the orthogonal

drawing, which was now engrained in architectural culture. Without the pressure of the subject matter

needing to be built (much like the anatomical drawings discussed in with regard to Peruzzi earlier) Piranesi

was free in his expression of his interpretation of the ruins of Rome. Piranesis early plates served to

Construct his vivid and highly individual vision of Rome as he supposed it to have been in ancient times,

add imagination to discoveries of the archaeologists

32

In this role as a vedutisti Piranesi was free to

dream.

Piranesis work culminates in his Carceri plates, see figure 18, produced from 1745 to the early 1760s.

The plates depict fantastical prisons entirely of Piranesis minds own conception. They play with so many

architectural qualities scale, light, shade and integration with the landscape; working to communicate an

31

(Powell & Leatherbarrow, 1983, p. 35)

32

(Powell & Leatherbarrow, 1983, p. 35)

35

Figure 18. Giovanni Battista

Piranesi , Carceri Plate VI -

The Smoking Fire (1761)

36

architectural idea, freed from constraints, existing in its own reality. The emotions of Piranesi exist and are

communicated in the drawing. It is able to provoke and influence the architectural profession without the

need for the plan, the section for the elevation to bring it from its reality to the one which we all share.

Piranesi has so clearly influenced many of the great dreamers throughout history through the Sublime,

Futurists, Russian Paper Architects, Archigram and the visionary architects of today. Piranesis work, on an

emotional level, had inspired many in the architectural profession. A notion that architecture was about

both the intellect and emotion

33

is something which places Piranesi at the forefront of Romanticism. As

the idea of the emotion in architecture grows Piranesis work becomes a point of reference for many

architects and architectural movements. Following Piranesi the direction and purpose of the avant-garde

of architectural drawing sees itself concerned much more with this communication of emotion and

experience, championed by Piranesi.

Modern successors of Piranesi would be the likes of Hugh Ferris (1889-1962), Lebbeus Woods and to a

certain extent Neil Spiller. They are all dreamers but a moment must be taken to dwell on Woods work,

seen in figures 19-21. Woods studied engineering and called himself and architect and artist, even though

he never received a degree in or was licensed to practice architecture, in our reality. Woods did however

have a background in engineering which no doubt helped him when imagining these architectural

landscapes.

His use of the reality of the paper within which to build creating dream like worlds which were

inhospitable has no doubt influenced the architectural profession. Creating these anarchical dream worlds

seems at least to be much more politically motivated. Each of his projects, since 1985, proposes new

social structures, implemented by new urban forms.

34

These projects do not feel like perverse conditions,

a consequence of the greed of humanity, instead optimistic they test the wonderful vitality of the human

condition and its ability to find new ways to dwell

35

.

Even though set in inhospitable futures with new technologies many of his drawings just seem to float,

Woods has this ability through his drawing to make the unlikely look likely

36

. Cook attributes this to his

background in structure; this is clear through Woods drawings. He has a clear understanding of structure

that is ever present, even when his architecture seems to just float. Through Woods the architecture of

dreams becomes not just likely, but real.

33

(Powell & Leatherbarrow, 1983, p. 35)

34

(Woods, 1992, p. 9)

35

(Spiller, Architectural Drawing: Grasping for the Fifth Dimension, 2013, p. 17)

36

(Cook, "Real Is Only Halfway There", 2012, p. 00:37:00)

37

Figure 21. Lebbeus Woods,

San Francisco Project:

Inhabiting the Quake,

Quake City, 1995.

Figure 20. Lebbeus Woods,

Radical Reconstruction,

1997

Figure 19. Lebbeus Woods,

Photon Kite, from the series

Centricity, 1988.

38

Drawing to Dream: Conclusion

Dreamers are free to explore whatever they desire through the reality of the paper, they play with

architecture is a way in which architects based in this world cannot. Often dreamers use the reality of the

paper to explore impossible ideas whether for political, economic, social or physical reasons, this does not

make their ideas any less valid. Often by looking at the work of dreamers throughout history their

aspirations provide an almost social commentary. The work of Piranesi explores the emotional, evocative

quality of architecture during a period which mathematical precision. Even recently with the work of

Woods which often explores today, mans ability to dwell in the most inhospitable of landscapes,

considering the threats both climatic and nuclear; things that in our reality may not be in the too distant

future.

Dreamers use the donegality of their drawing to allow viewers to inhabit these realities with them, to ask

the same questions and consider the same issues they do. Re-reading allows there drawings to continue

further than they ever would have imagined to the future and still have an effect on the way people draw

and design; need look no further than the work of Piranesi to see this. Dreamers act a conscience to the

profession and as such should constantly question the work and ideals of the building profession.

Drawing to Seduce: Student Work

It would almost be rude not to include or at least mention the sheer quality of drawing work produced

each year by the students of the profession. Their work after all is a purely academic exercise which is

inevitably communicated through a combination of drawings and models; as a result it produces some of

the most exquisite drawings. One would need to look no further than the RIBA Presidents Medals website

to see this. Although when in the context of the student, the role to seduce is one which is aimed at

examiners who may only have thirty minutes to mark their work; it is, as previously mentioned, applicable

to many situations both in practice and as a dreamer. This is through competitions and perhaps even the

need to seduce a client, to bring them round to a particular concept, architectural idea or even material.

Indeed all famous architects today were once students; see in figures 22 and 23 the diploma work of both

Peter Cook and Zaha Hadid. Cooks work is clearly at a progressive stage towards the work we see him

producing as a member of Archigram and the Zaha Malevichs Tektonik (1976) as we will find later is also

of the same vein in that respect. As a result it must be appropriate to look at the work of the cream of the

crop of todays students with respect to this idea of seduction within a drawing. After all we could be

looking at the Hadids and Cooks of the future.

Two of the best examples of this work are featured in the issue of AD: Drawing architecture. This is the

work of Pascal Bronner, and his New Malacovia seen in figures 24 and 25, and Tom Noonan, with his

Reforestation of the Thames Estuary seen in figures 26 and 27. Both use a combination of the digital and

39

Figure 22. Peter Cook,

Diploma Project (Unknown)

Figure 23. Zaha Hadid,

Diploma Project Malevichs

Tektonik (1977)

40

Figure 25. Pascal Bronner,

New Malacovia. (2009)

Figure 24. Pascal Bronner,

New Malacovia. (2009)

41

Figure 27. Tom Noonan, The

Reforestation of the

Thames Estuary (2010)

Figure 26. Tom Noonan, The

Reforestation of the

Thames Estuary (2010)

42

analogue in their drawing, the quality such that the difference between the two is unnoticeable, yet it is