Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Case Study Theorybuilding

Uploaded by

jdavince7Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Study Theorybuilding

Uploaded by

jdavince7Copyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 6

Advances in Developing Human Resources

Dooley / CASE STUDY RESEARCH

August 2002

Case Study Research

and Theory Building

Larry M. Dooley

The problem and the solution. This chapter overviews case

study research and proposes a manner in which case study

research can contribute to theory building in applied disciplines.

Although theory building using case study research has been discussed previously in the literature, there is no clarity as to how

case study research can be used to build theory. Moreover, it

should not be assumed that there is clarity on the processes of

case writing, case studies, or case study research. This chapter

presents definitions, purposes, and elements of case study

research for the purpose of understanding how case study

research can be used to build theory in applied disciplines.

Over the past several decades, the process of theory building has been examined from a multitude of perspectives. The literature provides ample evidence of the work of the theory-building scholars who developed and

refined a variety of theory-building methods and subprocesses. The unintentional, and not completely unexpected, result of such a diverse set of

efforts has been varying degrees of advancement, confusion, and misunderstanding among researchers as they began to combine the different components and techniques of single paradigm and multiparadigm theory-building

research methods. One important objective of this chapter is to clarify the

differences between a case study, case study research, and the role of case

study research in the process of theory building.

Case study research is one method that excels at bringing us to an understanding of a complex issue and can add strength to what is already known

through previous research. Case study research emphasizes detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships. Researchers have used the case study research method for many years

across a variety of disciplines. Pioneer work in this field is thought to be the

works of William Thomas and Robert Parks from the University of Chicago

in the early 1900s (Hamel, Dufour, & Fortin, 1993). However, as Herling,

Weinberger, and Harris (2000) noted, the concepts of a case, case study, and

case study research are often used interchangeably in the literature. For the

purpose of this chapter, case study research is defined as scholarly inquiry

Advances in Developing Human Resources Vol. 4, No. 3 August 2002 335-354

Copyright 2002 Sage Publications

336

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context,

when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident; and in which multiple sources of evidence are used (based on Yin,

1994, p. 33).

From the perspective of case study research, theory building is an arduous process. Case study research generally does not lend itself well to generalization or prediction. The researcher who embarks on case study research

is usually interested in a specific phenomenon and wishes to understand it

completely, not by controlling variables but rather by observing all of the

variables and their interacting relationships. From this single observation,

the start of a theory may be formed, and this may provoke the researcher to

study the same phenomenon within the boundaries of another case, and then

another, and another (single cases studied independently), or between individual cases (cross-case analysis) as the theory begins to take shape. In relation to grounded theory, Glaser (1978) submitted that what differentiated

grounded theory research from most other research was that it was explicitly

emergent without the tight focus on phenomena. That is why grounded theory research is generally more useful in the conceptual development phase

of theory building than case study research.

Theory building requires the ongoing comparison of data and theory

(Glaser & Strauss, 1967) and the continuous refinement between theory and

practice (Lynham, 2000). Case study research has the ability to embrace

multiple cases, to embrace quantitative and qualitative data, and to embrace

multiple research paradigms. Thus, case study research can contribute in a

holistic way to all phases of theory development. Table 1 lists the perspectives on case study research required to accept these assumptions.

New theory does not emerge quickly but will be developed over time as the

research is extended from one case to the next and more and more data are collected and analyzed. This form of reiteration and continuous refinement, more

commonly referred to as the multiple case study, occurs over an extended period

of time. The point being that it is only after the researcher has observed similar

phenomena in multiple settings will confirmation or disconfirmation of the new

theory begin to take shape and gain substance. As Kuhn (1996) noted,

New theory, however special its range of application, is seldom or never just an increment to

what is already known. Its assimilation requires the reconstruction of prior theory and the reevaluation of prior fact, an intrinsically revolutionary process that is seldom completed by a single man and never over night. (p. 7)

Similarly, the conduct of case study research can be expanded to engage multiple and simultaneous studies using multiple research paradigms (e.g., inductiveto-deductive and deductive-to-inductive strategies). This chapter examines case

study and case study research and the role of case study research in theory-building

research for applied disciplines.

Dooley / C ASE STUDY RESEARCH

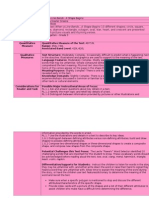

TABLE 1:

Yes

X

X

X

X

No

Perspectives on the Nature of Case Study Research

Perspective on Case Study Research

Case study research is a legitimate type of research.

Case study research can embrace one or more cases.

Case study research can rely on quantitative data, qualitative data, or

both.

Case study research can embrace multiple research paradigms (e.g.,

inductive-to-deductive and deductive-to-inductive strategies) on a

single or multiple cases.

Case study research can be applied to theory building.

Note: It is important to note that there is not consensus on these five perspectives and that the affirmation of all five helps distinguish this chapter.

The Concept of a Case

Cases (sometimes referred to as case writing) and case study differ in

many ways and resemble each other in other ways. We will look at them both

individually. The case itself is an account of an activity, event, or problem.

The case usually describes a series of events that reflect the activity or problem as it happened. As a matter of point, the case writer should be nonbiased

so the readers can have access to all the information and draw their own conclusions. A good case is generally taken from real life and includes the following components: setting, individuals involved, the events, the problems,

and the conflicts. Because cases reflect real-life situations, cases must represent good and bad practices, failures as well as successes. Facts must not

be changed to expose how the situation should have been handled (Kardos &

Smith, 1979).

Merseth (1994) defined a case as a descriptive research document, often

presented in narrative form, based on a real-life situation or event. Moreover, it attempts to convey a balanced, multidimensional representation of

the context, participants, and reality of the situation. Cases are created

explicitly for discussion and seek to include sufficient detail and information to elicit active analysis and interpretation by users with differing perspectives. This definition reaffirms three essential elements of cases: (a)

They are real, (b) they rely on careful research and study, and (c) they foster

the development of multiple perspectives by users (Merseth, 1994).

Case studies then emphasize the study and contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships. Stake (1994)

noted that case studies can be either simple or complex. Yin (1994) noted

that case studies can also be used for both theory testing or theory building.

Yet he made no distinction in describing the process steps even though the

theory tester and the theory builder start from different points in the general

method of theory-building research in applied disciplines (Lynham, 2002).

337

338

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

Case Study Research

Case study research, as defined by Yin (1994), Eisenhardt (1989), and

others, has well-defined steps. It is important to note, however, that case

study research does not imply the use of a particular type of evidence. And

this is important to note: Case study research can be accomplished using

quantitative and/or qualitative methodologies. A common misconception is that case studies are solely the result of ethnographies or of participant observation (Yin, 1981). Case study research can employ various datacollection processes such as participant observation, document analysis,

surveys, questionnaires, interviews, Delphi processes, and others. The

power of case study research is the ability to use all methodologies within

the data-collection process and to compare within case and across case for

research validity.

This unique characteristicthe ability of the researcher to use the observations of a single unit or subject, or contextual case, as the focal point of a

study, along with its plurality as a research methodhas enabled case study

research to transcend the boundaries of traditional research paradigms.

However, this uniqueness of case study research has also borne an uneasiness with the methodology as well. Unfortunately, the perception that has

been created is that as a research methodology, the case study research has

become, as the old saying goes, a jack-of-all-trades and a master of none

(Herling et al., 2000).

Case study research is an essential research methodology for applied disciplines. Regardless of how it is used, for either theory building or theory

testing, it is a process of scholarly inquiry and exploration whose underlying

purpose is to create new knowledge (Herling et al., 2000). Case study can

also be thought of as a research strategy. As a strategy, case study research

attempts to examine a contemporary phenomenon and the associated contexts that are not clearly evident. For example, experiments differ in that

they isolate the phenomenon from its context; histories also differ in that

they are limited to phenomena of the past. These distinctions among types of

evidence, data-collection method, and research strategy are critical in defining case study research.

Case study research, like all other forms of research, must be concerned with

issues such as methodological rigor, validity, and reliability. This is accomplished through the six elements below.

Determine and define the research questions

Select the cases and determine data-gathering and analysis

techniques

Prepare to collect data

Collect data in the field

Dooley / C ASE STUDY RESEARCH

Evaluate and analyze the data

Prepare the report

In the following sections, each of these elements is defined and discussed in

more detail. Following the discussion of the elements, the role of case study

research in theory building is presented.

Determine and Define

the Research Questions

The first step in case study research is not that different from any other

research study: to establish the focus or the intent of the project. Or as

Sherran Merriam (1998) has stated, To raise a question about something

that perplexes and challenges the mind (p. 57). The focus or intent is established once an intensive literature review has been completed and the problem has been well identified. This should be something that the research can

refer to as grounding during the process of the study. The research object of

the case is often a program, a group, or team, or may even be a person. Each

object is usually associated with political, social, historical, and personal

issues, making the case much more complicated than at first glance. The

researcher then investigates this subject using varying data-gathering techniques, both qualitative and quantitative in nature, all intended to supply the

necessary information to address the research questions.

The purpose of most case study research is to answer the why and how

questions. Clardy (1997) defined a case study to be a richly detailed story

about a specific situation or event in the workplace, describing who, what,

where, when, and how. Moreover, these questions are usually targeted to a

small number of events to study how the relationships are formed and why.

As mentioned previously, a literature review is also conducted in this step to

further refine the research questions and also to discover if past research has

been done that will add to the study. A literature review can also add face

validity to the project.

Select the Cases and Determine

Data-Gathering and Analysis Techniques

This is a very important phase and sets the tone for the rest of the study.

The researcher must select single or multiple cases that reflect the research

questions in Step 1. Moreover, this step also involves selecting the instruments and other data-gathering strategies that will be used. It is very important to realize in this step that if multiple cases are selected, each case must

be treated as a single case. The conclusion of each case can be considered in

339

340

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

light of the multiple-case phenomenon; however, each case must be examined on its own.

The researcher must also decide how to select the cases: Will they cover

similar or different geographic regions? Will they be the same size or different? Once the general description of the cases has been decided, Merriam

(1998) noted that case study research requires the identification of two units

of analysis. The first unit of analysis that must be identified is the case to be

studied. Then, unless the plan is to interview all participants in an organization, one would need to decide on a sampling technique to be representative

of the entire organization. Finally, Yin (1994) advocated that each case

study should either be similar to those previously studied by others or

should deviate in clear, operationally defined ways (p. 25). In this way, the

previous literature can be used as a guide for defining the new case and its

representative units of analyses.

A major strength of case study research is the ability to use multiple

sources and techniques. Case study research is viewed by many to be qualitative; however, and this is very important, it can also be quantitative. Tools

used in this type of data collection are usually surveys, interviews, document analysis, and observation, although standard quantitative measures

such as questionnaires are also used.

It is important that the researcher use specific tools for specific data collection. The study must be well constructed to ensure construct validity,

internal validity, external validity, and reliability. To pass these tests of

validity and reliability, explicit attention must be paid to the design of the

research study and to the processes used in the collection of the data, the

analysis of the data, and the reporting of the findings (Herling et al., 2000).

Construct validity requires the researcher to select the correct tool or

method for the concepts being studied. Internal validity demonstrates that

the conditions being observed will necessarily lead to other conditions and

is discovered by triangulating various pieces of evidence. The researcher

must establish a credible line of evidence that can be followed to these conclusions. External validity usually determines if the findings can be generalized beyond the one or multiple cases being studied. The more individuals

one can interview, the more and different observations that can be made and

still yield the same results, and the more external validity that can be demonstrated. Relating findings back to the literature also helps in external validity. Reliability refers to how well the procedures are documented to ensure

that the research can be replicated.

Prepare to Collect the Data

Case study researchers will typically begin a study using only one

method of data collection and will add others as the situation warrants it.

Dooley / C ASE STUDY RESEARCH

The added benefit of this process is that it can enhance the validity of case

study findings through triangulation. Preparation for the vast amounts of

data prior to collection will save the researcher much time and frustration

later. Due to the nature of case study research, the researcher will generate

large amounts of data from multiple sources. Time taken to plan prior to the

research will allow one to organize multiple databases and set categories for

sorting and managing the data.

It is also important to train individuals if people other than the researcher

will be doing fieldwork, collecting data, and performing document analyses. Qualifications also include being able to ask good questions and the

ability to interpret answers; document analysis includes the ability to read

between the lines to ascertain hidden meanings. When using other individuals for your fieldwork, it is a good idea to conduct a pilot test using some of

the same data-gathering techniques that will be used in the case study. In this

manner, problematic areas can be corrected.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the personal involvement of the

researcher in case study research data collection. A question of validity will

always arise if the reader considers the researcher too close to the content to

be subjective. One solution, as proposed by Gall, Borg, and Gall (1996), is a

subjectivity audit. This audit consists of taking notes about situations connected to ones research that brought about strong positive or negative feelings. The outcome could be a list of different aspects of the researcher that

describe areas in which the researchers own beliefs and background influenced his or her perceptions and actions in the research setting (Gall et al.,

1996).

There are really no firm rules about how much personal involvement or

disclosure by the researcher is appropriate. If self-disclosure passes a certain point, case study participants and readers of the report will view it as a

distraction, or worse, they may begin to question the researchers qualifications and validity of the studys findings. On the other hand, brief comments

by the researcher about his or her background and experiences relevant to

the case study may facilitate data collection and the readers ability to better

understand the findings (Gall et al., 1996).

Collect Data in the Field

Data collection is emergent in case study research. That means what the

researcher learns from the data collected at one point in time often is used to

determine subsequent data collection. The researcher therefore must collect

and store multiple sources of data, in a systematic manner. The storing of the

data is critical so as to allow for patterns and themes to emerge. One must

always keep the original object in mind and observe causal factors associated with the observed phenomenon. It is important to make formative eval-

341

342

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

uation checks so arrangements can be made in the event that factors arise

causing the manner in which the case is evaluated to change. Case study

research is flexible, but when changes are made, they must be documented

systematically. Field notes document this process; they record feelings and

hunches, pose questions, and document the work of the case.

The decision when to end the data-collection stage of case study research

involves both practical and theoretical considerations. Time and budgetary

constraints, or the observation that the participants patience is running out,

are among the practical considerations that can prompt a decision to end

data collection (Gall et al., 1996).

Yvonna Lincoln and Egon Guba (1985) have identified four criteria for determining when it is appropriate to end data collection.

1. Exhaustion of sources: Data sources (e.g., key informants, document

analysis) can be recycled and tapped many times, but at some point, it

should become clear that little more information or relevance will be

gained from further engagement with them.

2. Saturation of categories: Eventually, the categories used to code data

appear to be definitively established. When continuing data collection

produces only tiny increments of new information about categories in

comparison to the effort expended to get them, the researcher can feel

confident about ending data collection.

3. Emergence of regularities: At some point, the researcher encounters sufficient consistencies in the data that allows the researcher to develop a

sense of whether the phenomena represented by each construct occur

regularly or only occasionally.

4. Overextension: Even if new information is still coming in, the researcher

might develop a sense that the new information is far removed from the

central core of viable categories that have emerged and does not contribute usefully to the emergence of additional viable categories.

Evaluate and Analyze the Data

The researcher now evaluates the data using an array of interpretations to

find any and all relationships that may exist with reference to the research

questions. The discovery of constructs in qualitative data can be a significant outcome to a case study. The case study method, with its many different

data-collection and analyzing techniques, allows researchers opportunities

to triangulate data to strengthen the findings.

If the researcher used a multiple-case design, the generalizability of

constructs and themes across cases can be checked. This could include

whether a particular theme observed in one case was also present in other

cases. Multiple-case data can also be analyzed to detect rational or causal

patterns. The researchers constructs can be thought of as variables. Each

case can be given a score on each variable, say 0 = absent and 1 = present, or

0 = absent and 1 = present, to a moderate degree. If the scores on one variable

Dooley / C ASE STUDY RESEARCH

across all cases systematically covary with scores on another variable, the

researcher can infer a relational or causal pattern (Gall et al., 1996).

The two popular types of analysis used in case study research are structural analysis and reflective analysis. Structural analysis is the process of

examining case study data for the purpose of identifying patterns inherent in

discourse, text, events, or other phenomena. Structural analysis is used in

conversation analysis, ethnoscience, and other qualitative research

methods.

Reflective analysis is associated with several other qualitative methods

such as critical science and phenomenology. Reflective analysis could be

used in case studies to draw on other qualitative research traditions. Its use

involves a decision by the researcher to rely on his or her own intuition and

personal judgment to analyze the data rather than on technical procedures

involving explicit category classification systems (Gall et al., 1996).

It is important to sort data in as many ways as possible to seek unintended

outcomes that may not be apparent in the beginning. Additional interviews,

short and pointed, may be necessary at this point to dig deeper into a finding.

Another method is to use different investigators than the first time to gain a

different perspective. When multiple observations converge, strength in the

conclusions increases and confidence is established.

Prepare the Report

The goal of the report is to present the conclusions to the questions posed

by the research in a way that the reader can understand. Two types of reports

are popular for case study researchers. Reflective reporting, where the

writer will use literary devices to bring the case alive for the reader and the

strong presence of the researchers voice is apparent, and analytic reporting,

which notes an objective writing style (the researchers voice is either silent

or subdued). In the analytic style, the report generally has a conventional

organization: introduction, review of the literature, methodology, results,

and discussion (Gall et al., 1996).

In whatever style one chooses, the report should be presented so that the

reader could apply the same experience in his or her setting. It is important to

display enough evidence to convince the reader of the conclusions, to ensure

the reader that no stone was left unturned. As was the case in preparing for

data collection, it is advisable to have other individuals review the report to

ensure clarity and completeness.

Case studies are complex because they generally involve multiple

sources of data, may include multiple cases within a study, and produce

large amounts of data for analysis. Researchers from many disciplines use

the case study method of research to build on theory, to produce new theory,

to dispute or challenge theory, to explain a situation, to provide a basis to

343

344

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

apply solutions to situations, to explore, or to describe an object or phenomenon. The advantages of the case study method are its applicability to reallife, contemporary, human situations and its public accessibility through

written reports. Case study results relate directly to the common readers

everyday experience and facilitate an understanding of complex real-life

situations (Soy, 1996).

Using Case Study Research

for Theory Building

Case study research differs from other methods in its ability to expand

and contract. Using basic case study research methodology, a researcher can

take a contracted approach and conduct a single study in a single-case setting and could rely on just quantitative or qualitative data. When viewed this

way, case study research is seen as a rival or alternative to other methods to

meet the requirements of the specific theory-building phases set forth in the

general method of theory-building research in applied disciplines (see

Lynham, 2002).

An expanded view of case study research is to see it as a strategy for holding together a multicase and multiparadigm research effort. Such an effort

would most likely collect qualitative and quantitative data and would most

likely involve a research team instead of a single investigator. Once the prerequisites of the case setting(s) are established in an expanded case study

research effort, component studies will likely turn to procedures of a specific method employed (e.g., meta-analysis or social constructivist

methods).

The unique potential of case study research resides in the opportunity it offers

the researcher as a mixed methodologyan opportunity that allows the

researcher to observe the phenomenon from multiple perspectives. Although

additional care and rigor are required when using mixed evidence, the combination of data types can be highly synergistic (Eisenhardt, 1989, p. 538).

Mintzberg (1979) described synergy in this manner:

While systematic data creates the foundation for our theories it is the anecdotal data that enable

us to do the building. Theory building requires rich description. We uncover all kinds of relationships in our hard data, but it is only through the use of soft data that we are able to explain them.

(p. 587)

This does not in any way lessen the importance of using quantitative data

sources.

In promoting the use of mixed data for triangulation, Jik (1979) argued

that quantitative data and qualitative data were equally important to the

researcher, serving in a sense as a system of checks and balances. Quantita-

Dooley / C ASE STUDY RESEARCH

tive data, which can indicate relationships that may not be immediately evident to the researcher, can keep the researcher from being blinded by vivid

but potentially misleading impressions presented in the form of qualitative

data. At the same time, the qualitative data can be important in building an

understanding of the theory underlying the relationships revealed in the

quantitative data. It is important that the researcher consider both, although

as the researcher will generally collect literature that may inform but may

not be used, the same can be said of data collection.

The use of multiple-case and multiple-paradigm case study research generally requires a research team. Eisenhardt (1989) pointed out that the use of multiple investigators provides the researchertheory builder with two advantages.

First, multiple investigators

often have complementary insights which add to the richness of the data, and their different perspectives increase the likelihood of capitalizing on any novel insights which may be in the data.

Second, the convergence of observations from multiple investigators enhances confidence in the

findings, . . . while conflicting perceptions keep the group from premature closure. (p. 538)

In theory building, the case study researcher can leverage the advantage provided by a mixed-method approach by using one investigative team to collect

qualitative data and a second team to collect quantitative data, keeping the activities of each team separate through the beginning data collection and initial analysis. Following the initial analysis, the separate teams then converge and

exchange their data, analyze them, and compare their separate findings and preliminary conclusions. The reiterative process of theory building begins as each

team, equipped with new insight, collects, analyzes, and shares more data.

Eisenhardt (1989) suggested, Theory developed from case study

research is likely to have important strengths like novelty, testability, and

empirical validity (p. 548). The possibility of generating new theory

increases with case study research. This is because of the application context in which research is being conducted and because creative insight

often arises from the juxtaposition of contradictory or paradoxical evidence, and this constant juxtaposition of conflicting realities (differences

across cases, different types of data, and different investigators) tends to

unfreeze thinking (p. 546).

Under the right conditions, factors that generate strength can alternatively be viewed as weaknesses. Although the empirical validity of theory

generated from case study research is high because the process is intimately

tied with the evidence (Eisenhardt, 1989), the extensive use of empirical evidence can also produce a high level of complexity. Parsimony is a recognized characteristic of good theory (Patterson, 1986), but theory builders

working from the rich, voluminous data provided by case study research can

lose this perspective and may be unable to recognize which relationships are

the most important.

345

346

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

Beyond the Six Steps

This section concludes with two examples from the case study research

literature. The first (Figure 1) is from Yin (1989, p. 56), and it is his process

view of case study research.

This model illustrates that the case study research is being applied to

questions grounded in existing theory that has minimally been conceptualized and operationalized. The model also illustrates the potential of multiple

cases. Because this is not directly focused on theory building, the purpose

could be to gain answers to the questions or, if it is for theory building, to further enhance the conceptualization and operationalization of the theory.

The second is a table by Eisenhardt (1989, p. 535), and it is her analysis of

the steps, activities, and reasons for each when using case study research for

theory building (see Table 2). The focal point of this table is specifically

aimed at advancing the conceptualization and operationalization phases of

theory building by going through the application phase using the case

setting.

The Roles of Case Study Research

for Building Theory in Applied Disciplines

Is case study research then a research method or a theory-building

method? The contention is that case study research is a research methodology in its own right. When applied to theory building, case study research is

a research method and not by itself a theory-building methodology. This is

in contrast to the Dubin methodology presented in chapter 2 that is a theorybuilding research method that directly addresses all five of the theorybuilding phases. However, case study research is (a) a method for fulfilling

specific phases of the general method of theory building in applied disciplines and (b) a strategy for holding together multiple methods for the purpose of fulfilling all the phases.

Theory building has been operationally defined as the process of modelling

real-world phenomena (Torraco, 1997, p. 123). It has been argued that case

study research has a unique contribution to understanding real-world phenomena in context of the case. The question remains as to how case study research

and its methodology can be used within the framework of theory building.

Although Eisenhardt, Yin, Soy, and others have attested to the utility of case

study research as a means of building theories, there appears to be no clarity as to

the role case study research plays within the process of theory building. A reiteration of the position being taken here is that case study research can be the

following:

SINGLE-CASE DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

DESIGN

Conduct 1st

Case Study

interviews

observations

documents

Select

Cases

Conduct 2nd

Case Study

Develop

Theory

interviews

relate

study to

previous

theory

aim for

explanation

Design Data

Collection

Protocol

define

"process"

operationally

define

"process outcomes" (not

just ultimate

effects)

use formal

data collection

techniques

347

FIGURE 1: Case Study Method

Source: Yin (1989, p. 56).

observations

documents

Write

Individual

Case Report

CROSS-CASE ANALYSIS

Draw Cross-Case

Conclusions

pattern-match

policy implications

Modify Theory

Write

Individual

Case Report

pattern-match

Develop Policy

Implications

policy implications

replication

Write Cross-Case

Report

Conduct

Remaining

Case Studies

etc.

Write

Individual

Case Report

etc.

348

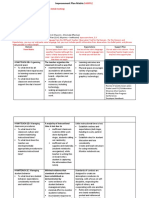

TABLE 2:

Process of Building Theory From Case Study Research

Step

Getting started

Selecting cases

Activity

Definition of research question

Possibly a priori constructs

Neither theory nor hypotheses

Specified population

Theoretical, not random, sampling

Crafting

instruments

and protocols

Entering the field

Multiple data collection methods

Qualitative and quantitative data combined

Multiple investigators

Overlap data collection and analysis, including field notes

Flexible and opportunistic data collection methods

Analyzing data

Within-case analysis

Cross-case pattern search using divergent techniques

Shaping hypotheses

Iterative tabulation of evidence for each construct

Replication, not sampling, logic across cases

Search evidence for why behind relationships

Comparison with conflicting literature

Enfolding literature

Comparison with similar literature

Reaching closure

Theoretical saturation when possible

Reason

Focuses efforts

Provides better grounding of construct measures

Retains theoretical flexibility

Constrains extraneous variation and sharpens external validity

Focuses efforts on theoretically useful cases, that is, those that

replicate or extend theory by filling conceptual categories

Strengthens grounding of theory by triangulation of evidence

Synergistic view of evidence

Fosters divergent perspectives and strengthens grounding

Speeds analyses and reveals helpful adjustments to data collection

Allows investigators to take advantage of emergent themes and

unique case features

Gains familiarity with data and preliminary theory generation

Forces investigators to look beyond initial impressions and see

evidence through multiple lenses

Sharpens construct definition, validity, and measurability

Confirms, extends, and sharpens theory

Builds internal validity

Builds internal validity, raises theoretical level, and sharpens

construct definitions

Sharpens generalizability, improves construct definition, and raises

theoretical level

Ends process when marginal improvement becomes small

Source: Eisenhardt (1989, p. 533). Academy of Management Review by Eisenhardt. Copyright 1989 by ACAD OF MGMT. Reproduced with permission of

ACAD OF MGMT in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center.

Dooley / C ASE STUDY RESEARCH

1. specific roles: case study research as a method for fulfilling specific

phases of the general method of theory building in applied disciplines,

and

2. overarching role: case study research as a strategy for bringing together

multiple methods for the purpose of fulfilling all the phases of the general method of theory building in applied disciplines.

Specific Roles

Case study research can logically fulfill four specific roles in meeting the

phase requirements of the general method of theory building in applied disciplines (Lynham, 2002). These roles are visualized in Figure 2 and discussed here.

Role 1. Case application of an already conceptualized and operationalized

theory (single or multiple cases). As the title of this phase indicates, the purpose

of this phase is to put the proposed theory into practice or application. This is

where most would see case study research making the greatest contribution. An

important outcome of this application phase is to enable the theorist to use the

experience and learning from the real-world application of the theory to further

inform, develop, and refine the theory (Lynham, 2002).

The application phase of the applied theory-building model really fits

with both of the last two steps of the six-step case study research process.

Although it may fit better with the last step, the final report, the application

phase also could add relevance to Step 5, analysis and synthesis of data. In

Step 5, the researcher will be observing the way the theory is used and,

through field observation and thick description, be able to critique the

application.

The application phase of theory building is presented in the text of the

final report where the observed theory was noted in practice and the implications of that practice. It is also in this Step 6 where the multiple observations

and multiple interviewers are taken into consideration.

Role 2. Confirmation or disconfirmation of an already conceptualized and operationalized theory (single or multiple cases). This phase of the applied theorybuilding model involves the planning, design, implementation, and evaluation

of the research study to confirm or reject the theoretical framework central to the

study (Lynham, 2002). This phase essentially is collecting the data, analyzing

the data, reaching the conclusions, and evaluating the results and process.

This phase emphasizes two of the six steps in the case study research process: Step 4, collect data in the field, and Step 5, evaluate and analyze the

data. Step 4 involves the collection of the data and observation of the patterns of the cases to refine the data-collection methods if necessary. This

step also requires the researcher to document, classify, and cross-reference

all data for retrieval in Step 5.

349

350

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

The environment in which we live, observe and experience the world.

Theorizing

to

Practice

DEDUCTIVE

Conceptual

Development

Operationalization

DEDUCTIVE

Continuous

Refinement

and

Development

1

Application

INDUCTIVE

2

Confirmation or

Disconfirmation

INDUCTIVE

Practice

to

Theorizing

FIGURE 2:

The Specific Roles of Case Study Research in Context of the General Method of

Theory-Building Research in Applied Disciplines

Note: Specific roles:case study research as a method for fulfilling specific phases of theory building in

applied disciplines. Role 1: application of an already conceptualized and operationalized theory (single or multiple cases), Role 2: confirmation or disconfirmation of a conceptualized or

operationalized theory (single or multiple cases), Role 3: application for the purpose of creating or

advancing conceptualizing and operationalizing of a theory (single or multiple cases), and Role 4:

continuous refinement and development of a fully developed theory (single or multiple cases).

Step 5 has the researcher analyzing the data for linkages, insights, and

other ways for connection with the research questions. This step also compares the data collected by quantitative as well as qualitative methods to discover if the findings are similar or different. Finally, the researcher will

answer all the how and why questions to satisfaction.

Role 3. Case application for the purpose of creating or advancing the conceptualization and operationalization of a theory (single or multiple cases). In

this role, case study research approaches the purpose and methodology of

grounded study researchthe conceptual development and operationalization

of a new theory. The primary difference has to do with case study research being

able to bring existing theory constructs to the inquiry as well as preplanned datacollection strategies.

Dooley / C ASE STUDY RESEARCH

Role 4. Continuous refinement and development of a fully developed theory

(single or multiple cases). Case study research can be used, with any of many

other research tools, to offer continued refinement and development. As most

theory is tested and built beginning with the theoretical part and then moving to

the research part later, case study research can be a testing bed for this theoretical

phase of continuous refinement and development. This is also a time for multiple cases in similar and dissimilar settings for the purpose of extending the application and utility of the theory.

Overarching Role

As illustrated in Figure 3, within multiparadigm theory-building

research, case study research can serve as a strategy for bringing together

and complementing multiple research methods for the purpose of fulfilling

the requirements of all the phases of the general method of theory building

in applied disciplines (Lynham, 2002). However, case study research in

itself is not a theory-building method and does not in itself represent all five

theory-building phases. Yet a multiparadigm approach organized under the

banner of case study research can easily embrace all five phases of applied

theory building.

For example, having a theory that is conceptually developed and

operationalized through quantitative research, meta-analysis research,

grounded theory research, or social constructionist research methods could

then be handed off for confirmation or disconfirmation and application

using case study research and its six steps: (a) Determine and define the

research questions, (b) select the cases and determine data-gathering and

analysis techniques, (c) prepare to collect data, (d) collect data in the field,

(e) evaluate and analyze the data, and (f) prepare the report. Other examples

are presented in Figure 3.

Implications for Human Research Development

Researchers, Practitioners, and Educators

Lynham (2000) outlined two key challenges for theory building in the

human resource development profession. The first is coping with the

researcher-practitioner partnership, and the second involves use of multiple

research paradigms to enrich theories. Although these challenges are large,

the use of case study research as an approach to building theory has some

critical advantages for meeting these demands.

First, the case study research approach to theory building requires contextual application (Herling et al., 2000; Yin, 1994); thus, when conducting

case study research, the researcher is almost always working with the practitioner. Case study research provides an excellent platform to nurture the

351

352

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

The environment in which we live, observe and experience the world.

Theorizing

to

Practice

DEDUCTIVE

Conceptual

Development

DEDUCTIVE

Operationalization

E

Continuous

Refinement

and

Development

C

D

Application

Confirmation or

Disconfirmation

4

INDUCTIVE

INDUCTIVE

Practice

to

Theorizing

FIGURE 3:

The Overarching Role of Case Study Research in Context of the General Method of

Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

Note: Overarching role:case study research as a strategy for bringing together multiple methods for

the purpose of fulfilling all the phases of the general method of theory building in applied disciplines.

Multiparadigm team research (in one or more case settings): (1) Use grounded theory research for

Phases A and B,(2) use meta-analysis research for Phases A and B,(3) synthesize multiple studies,(4)

use standard case study research for Phases D and C, (5) use a series of quasi-experimental studies

for Phases D and C, (6) synthesize findings, and (7) use multiple case studies for Phase E.

research-practitioner partnership. Second, theory building that relies on

case study research advocates the use of both qualitative and quantitative

data (Eisenhardt, 1989; Torraco, 1997) and can be adapted to use multiple

paradigms of research and interpretation. Third, because the case study

research approach often encompasses contradictory data when comparing

cross-case and multiparadigm data, the resultant theory is often creative and

novel (Eisenhardt, 1989).

References

Clardy, A. (1997). Studying your workforce: Applied research methods and tools for

training and development practitioners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dooley / C ASE STUDY RESEARCH

Eisenhardt, E. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

Gall, M. D., Borg, W. R., & Gall, J. P. (1996). Educational research: An introduction (6th

ed.). White Plains, NY: Longman.

Glaser, B. (1978). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs forcing. Mill Valley,

CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for

qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Hamel, J., Dufour, S., & Fortin, D. (1993). Case study methods. In Qualitative research

methods (Series 32). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Herling, R. W., Weinberger, L., & Harris, L. (2000). Case study research: Defined for

application in the field of HRD. St. Paul: University of Minnesota, Human Resource

Development Research Center.

Jik, T. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 602-611.

Kardos, G., & Smith, C. O. (1979). On writing engineering cases. Proceedings of the

American Society for Engineering Education National Conference on Engineering

Case Studies, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Kuhn, T. S. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions (3rd ed.). Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lynham, S. A. (2000). Theory building in the human resource profession. Human

Resource Development Quarterly, 11(2), 159-178.

Lynham, S. A. (2002). The general method of theory-building research in applied

disciplines. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 4(3), 221-241.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merseth, K. K. (1994). Cases, case methods, and the professional development of educators. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED401272)

Mintzberg, H. (1979). An emerging strategy of direct research. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 24, 580-589.

Patterson, C. H. (1986). Theories of counseling and psychotherapy (4th ed.). San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Soy, S. K. (1996). The case study as a research method. Retrieved December 1, 2001,

from University of Texas, Graduate School of Library and Information Science Web

site: http://www.gslis.utexas.edu/~ssoy/usesusers/l391d1b.htm

Stake, R. E. (1994). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of

qualitative research (pp. 236-246). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Torraco, R. J. (1997). Theory building research methods. In R. A. Swanson & E. F.

Holton (Eds.), Human resource development research handbook: Linking research

and practice (pp. 114-138). San Francisco: Berrett-Kohler.

Yin, R. K. (1981). The case study crisis: Some answers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 58-65.

353

354

Advances in Developing Human Resources

August 2002

Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research: Design and methods (Applied Social Research

Methods Series, 5). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (Applied Social Research

Methods Series, 5, 2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Feminist Philosopher Persona in Deleuze's WorkDocument153 pagesFeminist Philosopher Persona in Deleuze's WorkAragorn EloffNo ratings yet

- Business Communication 1Document172 pagesBusiness Communication 1ShashankNo ratings yet

- Theories of LearningDocument112 pagesTheories of LearningPalak50% (2)

- TTT A1 SBDocument83 pagesTTT A1 SBsusom_iulia100% (1)

- Project 3 Case Study Analysis Final SubmissionDocument4 pagesProject 3 Case Study Analysis Final Submissionapi-597915100No ratings yet

- Emotion Regulation in ACT - Steven C. HayesDocument13 pagesEmotion Regulation in ACT - Steven C. HayesVartax100% (2)

- Journal of The History of Ideas Volume 48 Issue 2 1987 (Doi 10.2307/2709557) Richter, Melvin - Begriffsgeschichte and The History of IdeasDocument18 pagesJournal of The History of Ideas Volume 48 Issue 2 1987 (Doi 10.2307/2709557) Richter, Melvin - Begriffsgeschichte and The History of IdeasJuan Serey AguileraNo ratings yet

- Kgmy Sample ReportDocument18 pagesKgmy Sample ReportAyesha AhmadNo ratings yet

- HomeworkifyDocument2 pagesHomeworkifyFindMyAIToolNo ratings yet

- The Social SelfDocument7 pagesThe Social SelfPatricia Ann PlatonNo ratings yet

- College of The Holy Spirit of Tarlac Basic Education Department S.Y. 2022-2023 Second SemesterDocument6 pagesCollege of The Holy Spirit of Tarlac Basic Education Department S.Y. 2022-2023 Second Semestercathymae riveraNo ratings yet

- Speech Production Models Blur Phonology and Phonetics BoundaryDocument12 pagesSpeech Production Models Blur Phonology and Phonetics BoundaryEslam El HaddadNo ratings yet

- The Zen of Hubert Benoit Joseph Hart PDFDocument27 pagesThe Zen of Hubert Benoit Joseph Hart PDFhnif2009No ratings yet

- When A Line Bends AnchorDocument2 pagesWhen A Line Bends Anchorapi-280395034No ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Employee Job Satisfaction at Ethio TelecomDocument25 pagesFactors Affecting Employee Job Satisfaction at Ethio Telecomdenekew lesemiNo ratings yet

- Componential analysis explainedDocument2 pagesComponential analysis explainedMar Crespo80% (5)

- Pangarap Pag Asa at Pagkakaisa Sa Gitna NG PandemyaDocument2 pagesPangarap Pag Asa at Pagkakaisa Sa Gitna NG Pandemyamarlon raguntonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Machine Learning: David Kauchak CS 451 - Fall 2013Document34 pagesIntroduction To Machine Learning: David Kauchak CS 451 - Fall 2013amirgeNo ratings yet

- Puzzle Design Challenge Brief R Molfetta WeeblyDocument4 pagesPuzzle Design Challenge Brief R Molfetta Weeblyapi-274367128No ratings yet

- SEO Jun Won - SeoulDocument12 pagesSEO Jun Won - SeoulKatherine ElviraNo ratings yet

- CREATIVE NON FICTION (Lecture # 8) - Building Dramatic SentencesDocument8 pagesCREATIVE NON FICTION (Lecture # 8) - Building Dramatic SentencesNelson E. MendozaNo ratings yet

- English RPH Year 3Document17 pagesEnglish RPH Year 3Sekolah Kebangsaan SekolahNo ratings yet

- Grammar Guide to Nouns, Pronouns, Verbs and MoreDocument16 pagesGrammar Guide to Nouns, Pronouns, Verbs and MoreAmelie SummerNo ratings yet

- Ba Notes On Principles of Management Course. 1Document123 pagesBa Notes On Principles of Management Course. 1Jeric Michael Alegre75% (4)

- English Writing Skills Class 11 ISCDocument8 pagesEnglish Writing Skills Class 11 ISCAnushka SwargamNo ratings yet

- Howard Philosophy of Education MatDocument4 pagesHoward Philosophy of Education Matapi-607077056No ratings yet

- Exquisite Corpse CollaborationDocument2 pagesExquisite Corpse CollaborationMeredith GiltnerNo ratings yet

- WowwDocument22 pagesWowwMirela Cojocaru StetcoNo ratings yet

- Computer: 01 Hour and A HalfDocument3 pagesComputer: 01 Hour and A HalfMohammedBaouaisseNo ratings yet

- Improvement Plan MatrixDocument3 pagesImprovement Plan MatrixJESSA MAE ORPILLANo ratings yet