Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CLASH v. OPRHP

Uploaded by

Tony MeyerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CLASH v. OPRHP

Uploaded by

Tony MeyerCopyright:

Available Formats

State of New York

Supreme Court, Appellate Division

Third Judicial Department

Decided and Entered: December 31, 2014

________________________________

519023

In the Matter of NYC

C.L.A.S.H., INC.,

Respondent,

v

OPINION AND ORDER

NEW YORK STATE OFFICE OF PARKS,

RECREATION AND HISTORIC

PRESERVATION et al.,

Appellants.

________________________________

Calendar Date:

Before:

November 12, 2014

Peters, P.J., Lahtinen, Garry, Rose and Lynch, JJ.

__________

Eric T. Schneiderman, Attorney General, Albany (Victor

Paladino of counsel), for appellants.

Joseph Law Group, LLP, New York City (Edward A. Paltzik of

counsel), for respondent.

__________

Peters, P.J.

Appeal from an order and judgment of the Supreme Court

(Ceresia Jr., J.), entered October 18, 2013 in Albany County,

which partially granted petitioner's application, in a combined

proceeding pursuant to CPLR article 78 and action for declaratory

judgment, to, among other things, declare invalid a certain

regulation promulgated by respondents.

Respondents, the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic

Preservation (hereinafter OPRHP) and its Commissioner, are

empowered by statute to "[o]perate and maintain . . . historic

sites and objects, parks, parkways and recreational facilities"

-2-

519023

(PRHPL 3.09 [2]) and to "[p]rovide for the health, safety and

welfare of the public using facilities under its jurisdiction"

(PRHPL 3.09 [5]). In February 2013, pursuant to this statutory

authority, OPRHP adopted a rule establishing smoke-free areas in

certain limited outdoor locations under its jurisdiction (see 9

NYCRR 386.1). Such regulation, among other things, also

prohibits smoking in each state park located in New York City,

with limited exceptions (see 9 NYCRR 386.1 [a] [2]).1 OPRHP

announced that this rule was needed in order to allow "patrons to

enjoy the outdoors, breathe fresh air, walk, swim, exercise and

experience [s]tate [p]arks' amenities and programs without being

exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke and tobacco litter" (NY Reg

Dec. 5, 2012 at 11). Following its adoption, petitioner, an

organization dedicated to advancing and promoting the interests

and rights of smokers, commenced this combined proceeding

pursuant to CPLR article 78 and action for declaratory judgment

seeking declaratory and injunctive relief. Petitioner alleged

that 9 NYCRR 386.1 violated the constitutional principle of

separation of powers because respondents lacked authority to

regulate smoking in the absence of an enactment by the

Legislature on that issue, and that the regulation was arbitrary

and capricious due to its inconsistent treatment of parks located

in New York City. Finding that 9 NYCRR 386.1 was an

unconstitutional exercise of authority by OPRHP, Supreme Court

partially granted the petition, prompting this appeal by

As relevant here, 9 NYCRR 386.1 provides that "(a)

Smoking of tobacco or any other product is prohibited in the

following outdoor locations under the jurisdiction of the office:

(1) any No Smoking Area designated by the [C]ommissioner.

Examples of areas that may be designated as No Smoking Areas

include: playgrounds, swimming pool decks, beaches, sport or

athletic fields and courts, recreational facilities, picnic

shelters, fishing piers, marinas, historic sites, group camps,

park preserves, gardens, concessions, educational programming, or

other areas where visitors congregate, including within fifty

feet of entrances to buildings; and (2) each state park in New

York City, with the exception that the [C]ommissioner may allow

smoking in limited areas within each park."

-3-

519023

respondents.2

"The cornerstone of administrative law is derived from the

principle that the Legislature may declare its will, and after

fixing a primary standard, endow administrative agencies with the

power to fill in the interstices in the legislative product by

prescribing rules and regulations consistent with the enabling

legislation" (Matter of Nicholas v Kahn, 47 NY2d 24, 31 [1979];

accord Matter of Medical Socy. of State of N.Y. v Serio, 100 NY2d

854, 865 [2003]; see NY Const, art III, 1). As the Court of

Appeals has recently reaffirmed, when determining whether an

administrative agency has violated the constitutional principle

of separation of powers, we must consider the "coalescing

circumstances" set forth in Boreali v Axelrod (71 NY2d 1, 11

[1987]), namely, (1) whether the respondents improperly engaged

in the balancing of their stated goal with competing social

concerns and acted "solely on [their] own ideas of sound public

policy"; (2) whether the respondents engaged in the

"interstitial" rulemaking typical of administrative agencies or

instead "wrote on a clean slate, creating [their] own

comprehensive set of rules without benefit of legislative

guidance"; (3) whether the challenged regulation concerns "an

area in which the Legislature ha[s] repeatedly tried and failed

to reach agreement in the face of substantial public debate and

vigorous lobbying by a variety of interested factions"; and (4)

whether the respondents overstepped their bounds because the

development of the regulation did not require the exercise of

expertise or technical competence by the administrative agency

(id. at 12-14 [internal quotation marks and citations omitted];

see Matter of New York Statewide Coalition of Hispanic Chambers

of Commerce v New York City Dept. of Health & Mental Hygiene, 23

NY3d 681, 692-693 [2014]; Matter of Citizens for an Orderly

Energy Policy v Cuomo, 159 AD2d 141, 152-157 [1991], affd 78 NY2d

398 [1991]). In determining whether "the difficult-to-define

2

While Supreme Court granted petitioner much of the relief

it requested, the court did not address whether the regulation

was arbitrary and capricious. Additionally, it declined to issue

an order precluding respondents from enforcing any similar rules

in the future.

-4-

519023

line between administrative rule-making and legislative policymaking has been transgressed," this Court should view these

circumstances "in combination" (Boreali v Axelrod, 71 NY2d at

11), while ever mindful that "'it is the province of the people's

elected representatives, rather than appointed administrators, to

resolve difficult social problems by making choices among

competing ends'" (Matter of New York Statewide Coalition of

Hispanic Chambers of Commerce v New York City Dept. of Health &

Mental Hygiene, 23 NY3d at 697, quoting Boreali v Axelrod, 71

NY2d at 13).

Applying the four Boreali considerations, we find no

usurpation of the Legislature's prerogative by respondents'

promulgation of 9 NYCRR 386.1. First, we find no indication that

OPRHP improperly balanced economic and social concerns against

its stated goal in order to act on its own ideas of sound public

policy.3 We specifically reject petitioner's assertion that,

because the regulatory impact statement discussed the proposed

operational savings that would result from the regulation,

respondents gave improper consideration to economic concerns, as

this is not the kind of improper balancing proscribed under

Boreali (see Matter of New York Statewide Coalition of Hispanic

Chambers of Commerce v New York City Dept. of Health & Mental

Hygiene, 23 NY3d at 697-698). Given the nature of OPRHP's

facilities, designating the more populated areas as nonsmoking,

while still permitting smoking in other areas of the facilities,

allows all patrons to enjoy the parks regardless of their smoking

preference. As for the New York City parks, the near-complete

ban on smoking there even more strongly supports respondents'

goal, by recognizing that these smaller parks are more thoroughly

populated and, therefore, leave little space for patrons to avoid

tobacco smoke and litter. Meanwhile, these same characteristics

allow smokers to easily exit the parks in order to access an area

where smoking is permitted.

Supreme Court did not address the first Boreali factor,

as petitioner apparently asserted that such factor was not

relevant to this proceeding.

-5-

519023

Thus, the regulation at issue does not represent "a

regulatory scheme laden with exceptions based solely upon

economic and social concerns" (Boreali v Axelrod, 71 NY2d at 1112), nor does it contain "indicators of political compromise"

(Matter of New York Statewide Coalition of Hispanic Chambers of

Commerce v New York City Dept. of Health & Mental Hygiene, 23

NY3d at 697). Rather, all aspects of the regulation are grounded

in OPRHP's stated purpose to allow all patrons to enjoy the

fresh air and natural beauty of its outdoor facilities and are

consistent with OPRHP's "legislatively expressed goals" (Boreali

v Axelrod, 71 NY2d at 12) to operate and maintain the parks and

to provide for the health, safety and welfare of their patrons.

Moreover, the choices made by OPRHP here were "not very difficult

or complex" as "there is minimal interference with the personal

autonomy of those whose health is being protected, and [the]

value judgments concerning the underlying ends are widely shared"

(Matter of New York Statewide Coalition of Hispanic Chambers of

Commerce v New York City Dept. of Health & Mental Hygiene, 23

NY3d at 699). Furthermore, the record does not indicate that the

designation of no smoking areas continues to be the subject of

great public debate, as it was when the Court of Appeals struck

down a smoking regulation by the Public Health Council in Boreali

over a quarter century ago. In fact, 91% of the comments that

respondents received on this rule were favorable and many

commenters expressed their desire that smoking be banned outright

in all state parks.4

Next, we do not find that OPRHP "wrote on a clean slate,

creating its own comprehensive set of rules" (Boreali v Axelrod,

71 NY2d at 13). The Legislature has instructed OPRHP to

"[o]perate and maintain" its sites while "[p]rovid[ing] for the

health, safety and welfare of the public using [those sites]"

(PRHPL 3.09 [2], [5]). Additionally, the Legislature has taken

action subsequent to Boreali expressing its determination

that tobacco smoke, including secondhand smoke, is hazardous to

4

We note that several other agencies have also adopted

rules that regulate smoking in areas under their jurisdiction

(see e.g. 9 NYCRR 300-3.1 [n]; 4064.5; 14 NYCRR 633.23; 18 NYCRR

414.11).

-6-

519023

one's health (see L 1989, ch 244, 1; see generally Public

Health Law art 13-E). While most of the Legislature's action

thus far has focused on prohibiting smoking indoors, it has also

prohibited smoking at playgrounds, subject to certain conditions,

and has further instructed that "[s]moking may not be permitted

where prohibited by any other law, rule or regulation of any

state agency or any political subdivision of the state" (Public

Health Law 1399-r [3]). While there may not exist a specific

statutory delegation of authority directing respondents to

establish no smoking areas, "[t]he Legislature is not required in

its enactments to supply agencies with rigid marching orders"

(Matter of Citizens For An Orderly Energy Policy v Cuomo, 78 NY2d

398, 410 [1991]; accord Matter of New York Statewide Coalition of

Hispanic Chambers of Commerce v New York City Dept. of Health &

Mental Hygiene, 23 NY3d at 700). Moreover, OPRHP has regulated

the activity of patrons at its parks and facilities pursuant to

its statutory authority for decades without interference from the

Legislature (compare Matter of Medical Socy. of State of N.Y. v

Serio, 100 NY2d at 866).5

Nor do we find that OPRHP has improperly intruded upon an

area that is a matter of legislative debate. Over the years,

while several bills concerning prohibitions against smoking in

outdoor areas have been introduced in both the Senate and the

Assembly, most died in committee. We are not persuaded that

these failed bills are enough to warrant the conclusion that

OPRHP has exceeded its authority (see Rent Stabilization Assn. of

N.Y. City v Higgins, 83 NY2d 156, 170 [1993], cert denied 512 US

Among the activities prohibited or regulated by OPRHP at

the sites under its jurisdiction are: polluting, littering,

destroying property, hitchhiking, gambling, possessing animals,

nudity, using all-terrain vehicles, firearms and weapons, and

artificial swimming aids, games and athletic activity, model

boating, riding saddle horses, roller skating, kite flying,

swimming, boating, golfing, bicycling and taxis (see 9 NYCRR

375.1, 377.1).

-7-

519023

1213 [1994]).6 Most notably, the Legislature's Administrative

Regulations Review Commission, which is tasked with overseeing

the rule-making process and examining proposed rules for, among

other things, "statutory authority [and] compliance with

legislative intent" (Legislative Law 87 [1]), reviewed 9 NYCRR

386.1 and "urge[d its] adoption."

Finally, we find that there was sufficient agency

expertise required to enact this rule such that it did not

intrude upon legislative authority. OPRHP's expertise lies in

acquiring, operating and maintaining state parks and historic

sites (see PRHPL 3.09). OPRHP observed that, "[i]n addition to

potential health risks, exposure to tobacco smoke negatively

impacts the experience of park visitors, as does the litter from

discarded cigarettes and cigar butts," and that such visitors

would "prefer not to have their park experience degraded by

unhealthy and irritating exposure to second hand tobacco smoke

and litter" (NY Reg, Dec. 5, 2012 at 11). In developing the

challenged regulation, OPRHP considered the nature of the

properties under its jurisdiction in order to determine how best

to locate the no smoking areas; this is evidenced by the rule's

treatment of parks in New York City, which differ in size and

setting from the parks elsewhere in the state. Accordingly, upon

applying the Boreali considerations, we conclude that OPRHP has

acted within its competence and authority by regulating the

smoking activity of patrons at its parks and facilities.

We next consider petitioner's assertion that 9 NYCRR 386.1

is arbitrary and capricious because it treats state parks located

in New York City differently from those throughout the rest of

the state. "It is well-settled that a [s]tate regulation should

be upheld if it has a rational basis and is not unreasonable,

arbitrary, capricious or contrary to the statute under which it

was promulgated" (Kuppersmith v Dowling, 93 NY2d 90, 96 [1999]

[citations omitted]; see Matter of Ford v New York State Racing &

6

We note that many of these bills contained much greater

restrictions than the regulation at issue here, including

complete bans of smoking in all public parks, not just those

under the jurisdiction of OPRHP.

-8-

519023

Wagering Bd., 107 AD3d 1071, 1073 [2013], affd ___ NY3d ___, 2014

Slip Op 08870 [2014]). Pursuant to 9 NYCRR 386.1, smoking is

prohibited throughout the parks located in New York City, except

that the Commissioner may allow smoking in limited areas,

whereas, in parks throughout the rest of the state, smoking is

permitted except in designated nonsmoking areas. According to

respondents, this greater restriction in New York City parks is

due to their smaller size, which permits patrons to easily walk

to an area outside of a park to smoke. Additionally, since

smoking is already prohibited in New York City's public parks,

respondents determined that the nearby state parks should be

managed in a consistent manner. Inasmuch as the different

treatment of parks located in New York City is not unreasonable,

arbitrary or capricious, we decline to annul the regulation on

that basis (see Matter of Ford v New York State Racing & Wagering

Bd., 107 AD3d at 1074-1075; Matter of Sullivan Fin. Group, Inc. v

Wrynn, 94 AD3d 90, 98 [2012]).

Lahtinen, Garry, Rose and Lynch, JJ., concur.

ORDERED that the order and judgment is modified, on the

law, without costs, by reversing so much thereof as partially

granted petitioner's application; petition dismissed in its

entirety and it is declared that 9 NYCRR 386.1 has not been shown

to be unconstitutional; and, as so modified, affirmed.

ENTER:

Robert D. Mayberger

Clerk of the Court

You might also like

- Russel H. Beatie, Jr. v. City of New York Rudolph Giuliani, Mayor, Mayor of The City of New York Council of The City of New York, 123 F.3d 707, 2d Cir. (1997)Document8 pagesRussel H. Beatie, Jr. v. City of New York Rudolph Giuliani, Mayor, Mayor of The City of New York Council of The City of New York, 123 F.3d 707, 2d Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument26 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument10 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- New Mexico Citizens For Clean Air and Water Pueblo of San Juan v. Espanola Mercantile Company, Inc., Doing Business As Espanola Transit Mix Co., 72 F.3d 830, 10th Cir. (1996)Document8 pagesNew Mexico Citizens For Clean Air and Water Pueblo of San Juan v. Espanola Mercantile Company, Inc., Doing Business As Espanola Transit Mix Co., 72 F.3d 830, 10th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- BOE OrderDocument4 pagesBOE OrderBrigid BerginNo ratings yet

- United States District Court District of New JerseyDocument20 pagesUnited States District Court District of New JerseyJack RyanNo ratings yet

- Elbert Strickland v. City of Albuquerque, and Arthur Blumenfeld, PH.D., Chief Administrative Officer, 130 F.3d 1408, 10th Cir. (1997)Document8 pagesElbert Strickland v. City of Albuquerque, and Arthur Blumenfeld, PH.D., Chief Administrative Officer, 130 F.3d 1408, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not Precedential: Circuit JudgesDocument14 pagesNot Precedential: Circuit Judgescharlie minatoNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law in Context, 2nd Edition - Part18Document15 pagesAdministrative Law in Context, 2nd Edition - Part18spammermcspewsonNo ratings yet

- Borello Et Al Vs NYSDocument5 pagesBorello Et Al Vs NYSKyle BeckerNo ratings yet

- Mordukhaev v. DausDocument9 pagesMordukhaev v. Dausannax9No ratings yet

- Thrun V Cuomo MTD DecisionDocument9 pagesThrun V Cuomo MTD DecisionCasey Seiler100% (1)

- Vance Murphy, D/B/A The Store v. The Honorable Scott Matheson, Individually and As Governor of The State of Utah, 742 F.2d 564, 10th Cir. (1984)Document25 pagesVance Murphy, D/B/A The Store v. The Honorable Scott Matheson, Individually and As Governor of The State of Utah, 742 F.2d 564, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Enrique Molina-Estrada v. Puerto Rico Highway Authority, 680 F.2d 841, 1st Cir. (1982)Document8 pagesEnrique Molina-Estrada v. Puerto Rico Highway Authority, 680 F.2d 841, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Affirmation in Support of Defendants Motion For Summary JudgmentDocument4 pagesAffirmation in Support of Defendants Motion For Summary JudgmentRuss Wishtart100% (1)

- Richard O'Neill v. Town of Nantucket, 711 F.2d 469, 1st Cir. (1983)Document5 pagesRichard O'Neill v. Town of Nantucket, 711 F.2d 469, 1st Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument31 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- For Leg ProfDocument35 pagesFor Leg Profadonis.orillaNo ratings yet

- Arthur Silva v. James T. Lynn, 482 F.2d 1282, 1st Cir. (1973)Document9 pagesArthur Silva v. James T. Lynn, 482 F.2d 1282, 1st Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Daniel Friedlander v. Joseph Cimino, M.D., Individually and As Commissioner of The Department of Health of The City of New York, 520 F.2d 318, 2d Cir. (1975)Document4 pagesDaniel Friedlander v. Joseph Cimino, M.D., Individually and As Commissioner of The Department of Health of The City of New York, 520 F.2d 318, 2d Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- DA William Fitzpatrick & Erik Mitchell M.D. (Doc 107) Robert F. Julian Esq. DA's CounselDocument8 pagesDA William Fitzpatrick & Erik Mitchell M.D. (Doc 107) Robert F. Julian Esq. DA's CounselDesiree YaganNo ratings yet

- New York State Association For Retarded Children, Inc. v. Hugh L. Carey, Individually and As Governor of The State of New York, 711 F.2d 1136, 2d Cir. (1983)Document28 pagesNew York State Association For Retarded Children, Inc. v. Hugh L. Carey, Individually and As Governor of The State of New York, 711 F.2d 1136, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Highlights of The Rules OfProcedure For Environmental CasesDocument32 pagesHighlights of The Rules OfProcedure For Environmental CasesGyLyoung Sandz-GoldNo ratings yet

- George R. Zanghi v. The Incorporated Village of Old Brookville, The Old Brookville Police Department, John Kenary and Kenneth Wile, 752 F.2d 42, 2d Cir. (1985)Document7 pagesGeorge R. Zanghi v. The Incorporated Village of Old Brookville, The Old Brookville Police Department, John Kenary and Kenneth Wile, 752 F.2d 42, 2d Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Catherine JACKSON, On Behalf of Herself and All Others Similarly Situated, Appellant, v. Metropolitan Edison Company, A Pennsylvania CorporationDocument13 pagesCatherine JACKSON, On Behalf of Herself and All Others Similarly Situated, Appellant, v. Metropolitan Edison Company, A Pennsylvania CorporationScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Eduardo Angel and George Lopez, On Behalf of Themselves and All Others Similarly Situated v. Earl L. Butz, United States Secretary of Agriculture, 487 F.2d 260, 10th Cir. (1973)Document5 pagesEduardo Angel and George Lopez, On Behalf of Themselves and All Others Similarly Situated v. Earl L. Butz, United States Secretary of Agriculture, 487 F.2d 260, 10th Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument11 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- American Commuters Association, Inc. v. Arthur Levitt, Individually and As Comptroller of The State of New York, 405 F.2d 1148, 2d Cir. (1969)Document7 pagesAmerican Commuters Association, Inc. v. Arthur Levitt, Individually and As Comptroller of The State of New York, 405 F.2d 1148, 2d Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Equitable and Legal Rights and Remedies Under The New Federal ProcedureDocument19 pagesEquitable and Legal Rights and Remedies Under The New Federal ProcedureAnonymous u42TegT28No ratings yet

- Lex Loci and Global Economic Welfare in Transnational TortsDocument11 pagesLex Loci and Global Economic Welfare in Transnational TortsPulkit PareekNo ratings yet

- Sandoval Notes SupplementalDocument26 pagesSandoval Notes SupplementalSui100% (1)

- Against Settlement Owen FissDocument20 pagesAgainst Settlement Owen FissFelipe Bernardes - Direito e Processo do TrabalhoNo ratings yet

- Letter To Supreme Court NYR&P 3-27-2019Document15 pagesLetter To Supreme Court NYR&P 3-27-2019wolf woodNo ratings yet

- Hynes v. Mayor and Council of Oradell, 425 U.S. 610 (1976)Document22 pagesHynes v. Mayor and Council of Oradell, 425 U.S. 610 (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Babcock Vs Jackson Full TextDocument10 pagesBabcock Vs Jackson Full TextSyElfredGNo ratings yet

- Gerald K. Adamson, Plaintiff-Appellant/cross-Appellee v. Otis R. Bowen, M.D., Secretary of Health & Human Services, Defendant - Appellee/cross-Appellant, 855 F.2d 668, 10th Cir. (1988)Document14 pagesGerald K. Adamson, Plaintiff-Appellant/cross-Appellee v. Otis R. Bowen, M.D., Secretary of Health & Human Services, Defendant - Appellee/cross-Appellant, 855 F.2d 668, 10th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Public Utilities and State Action - The Supreme Court Takes A StanDocument16 pagesPublic Utilities and State Action - The Supreme Court Takes A Stannoman aliNo ratings yet

- State of New York v. United States Metals Refining Company and Amax, Inc. State of New Jersey, Dept. of Environmental Protection, Intervenor, 771 F.2d 796, 3rd Cir. (1985)Document13 pagesState of New York v. United States Metals Refining Company and Amax, Inc. State of New Jersey, Dept. of Environmental Protection, Intervenor, 771 F.2d 796, 3rd Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Suburban Restoration Co., Inc. v. Acmat Corporation, Laborers' International Union of North America, Local 665 Afl-Cio and Robert D. Witte, 700 F.2d 98, 2d Cir. (1983)Document6 pagesSuburban Restoration Co., Inc. v. Acmat Corporation, Laborers' International Union of North America, Local 665 Afl-Cio and Robert D. Witte, 700 F.2d 98, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bi-Rite Enterprises, Inc. v. Bruce Miner Company, Inc., 757 F.2d 440, 1st Cir. (1985)Document9 pagesBi-Rite Enterprises, Inc. v. Bruce Miner Company, Inc., 757 F.2d 440, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 6-4-15 - Additional Practical Materials - J. WicksDocument24 pages6-4-15 - Additional Practical Materials - J. WicksAndrea NúñezNo ratings yet

- United States International Trade Commission Washington, D.CDocument6 pagesUnited States International Trade Commission Washington, D.CFlorian MuellerNo ratings yet

- Citizens For A Better Environment, Inc., On Behalf of Itself and Its Employees v. Nassau County, 488 F.2d 1353, 2d Cir. (1973)Document17 pagesCitizens For A Better Environment, Inc., On Behalf of Itself and Its Employees v. Nassau County, 488 F.2d 1353, 2d Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 41 3 - 16 - 22 Request Reconsider Oversize BriefDocument10 pages41 3 - 16 - 22 Request Reconsider Oversize BriefJosé DuarteNo ratings yet

- United States v. Green Drugs and Raymond S. Kauffman, 905 F.2d 694, 3rd Cir. (1990)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Green Drugs and Raymond S. Kauffman, 905 F.2d 694, 3rd Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Memorandum Ii: Floro", For Brevity) by HIMSELF, As Litigant, Unto This Honorable CourtDocument44 pagesMemorandum Ii: Floro", For Brevity) by HIMSELF, As Litigant, Unto This Honorable CourtJudge Florentino Floro100% (3)

- John Novosel v. Nationwide Insurance Company, 721 F.2d 894, 3rd Cir. (1983)Document15 pagesJohn Novosel v. Nationwide Insurance Company, 721 F.2d 894, 3rd Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 845, Docket 84-7866Document6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 845, Docket 84-7866Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit.: Nos. 74-1130 To 74-1132Document6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit.: Nos. 74-1130 To 74-1132Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- LLC 2 PDFDocument4 pagesLLC 2 PDFChris BraggNo ratings yet

- Cannabis Motion DeniedDocument20 pagesCannabis Motion DeniedWGRZ-TVNo ratings yet

- Latino Project, Inc. v. City of Camden, Melvin Primas, and William Hanowsky, 701 F.2d 262, 3rd Cir. (1983)Document6 pagesLatino Project, Inc. v. City of Camden, Melvin Primas, and William Hanowsky, 701 F.2d 262, 3rd Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- El Dia, Inc. v. Rafael Hernandez Colon, 963 F.2d 488, 1st Cir. (1992)Document14 pagesEl Dia, Inc. v. Rafael Hernandez Colon, 963 F.2d 488, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ivette Santiago-Negron v. Modesto Castro-Davila, Etc., 865 F.2d 431, 1st Cir. (1989)Document24 pagesIvette Santiago-Negron v. Modesto Castro-Davila, Etc., 865 F.2d 431, 1st Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- US V Sheldon Silver ComplaintDocument35 pagesUS V Sheldon Silver ComplaintNick ReismanNo ratings yet

- From The NYS Appellate DivisionDocument7 pagesFrom The NYS Appellate DivisionTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Assemblymember Lentol J 2013Document16 pagesAssemblymember Lentol J 2013Tony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Kent v. CuomoDocument6 pagesKent v. CuomoTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Branding BibleDocument87 pagesBranding BibleTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Veto #570-586Document17 pagesVeto #570-586Tony MeyerNo ratings yet

- The Governor'S Commission On Youth, Public Safety, and JusticeDocument25 pagesThe Governor'S Commission On Youth, Public Safety, and JusticeTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- 2015 Opportunity Agenda BookDocument550 pages2015 Opportunity Agenda BookTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Report of Commission On Youth Public Safety and JusticeDocument176 pagesReport of Commission On Youth Public Safety and JusticeTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Dwyer LetterDocument3 pagesDwyer LetterTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- NYSED Response To MalatrasDocument20 pagesNYSED Response To MalatrasTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- 2015 Proposed Budget PDFDocument74 pages2015 Proposed Budget PDFjspectorNo ratings yet

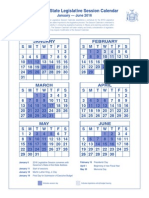

- 2016 Legislative Session CalendarDocument1 page2016 Legislative Session CalendarMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Approval #29 33Document5 pagesApproval #29 33Tony MeyerNo ratings yet

- A Public Health Review of High Volume Hydraulic Fracturing For Shale Gas DevelopmentDocument184 pagesA Public Health Review of High Volume Hydraulic Fracturing For Shale Gas DevelopmentMatthew LeonardNo ratings yet

- NYS 2014 Regional Economic Development Council AwardsDocument130 pagesNYS 2014 Regional Economic Development Council AwardsrickmoriartyNo ratings yet

- Inspector General LetterDocument3 pagesInspector General LetterTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Schneiderman To Cuomo 12-08-14Document2 pagesSchneiderman To Cuomo 12-08-14Tony MeyerNo ratings yet

- 12-1-14 CJN Press ReleaseDocument10 pages12-1-14 CJN Press ReleaseTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- 2014-11-20 (125) Discovery OrderDocument19 pages2014-11-20 (125) Discovery OrderTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- ESDC Golden GlobesDocument4 pagesESDC Golden GlobesTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- State of New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Third Judicial DepartmentDocument7 pagesState of New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Third Judicial DepartmentJon CampbellNo ratings yet

- 2014.11.10 Letter To Judge TreeceDocument5 pages2014.11.10 Letter To Judge TreeceTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- 2014-11-06 LTR From GFC To Judge TreeceDocument7 pages2014-11-06 LTR From GFC To Judge TreeceTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Approval #8 13Document6 pagesApproval #8 13Tony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Rensselaer Casino LOSDocument2 pagesRensselaer Casino LOSTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Remarks of Loretta e Lynch MorelandDocument9 pagesRemarks of Loretta e Lynch MorelandTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- News 141029 MOL in Support of MTDDocument70 pagesNews 141029 MOL in Support of MTDJon CampbellNo ratings yet

- Loguidice SuitDocument17 pagesLoguidice SuitTony MeyerNo ratings yet

- Top 35 Brokerage Firms in PakistanDocument11 pagesTop 35 Brokerage Firms in PakistannasiralisauNo ratings yet

- 3 Course Contents IIIBDocument5 pages3 Course Contents IIIBshahabNo ratings yet

- Benchmarking Guide OracleDocument53 pagesBenchmarking Guide OracleTsion YehualaNo ratings yet

- Q&A Session on Obligations and ContractsDocument15 pagesQ&A Session on Obligations and ContractsAnselmo Rodiel IVNo ratings yet

- Tyron Butson (Order #37627400)Document74 pagesTyron Butson (Order #37627400)tyron100% (2)

- BS EN 364-1993 (Testing Methods For Protective Equipment AgaiDocument21 pagesBS EN 364-1993 (Testing Methods For Protective Equipment AgaiSakib AyubNo ratings yet

- Elaspeed Cold Shrink Splices 2010Document3 pagesElaspeed Cold Shrink Splices 2010moisesramosNo ratings yet

- MSBI Installation GuideDocument25 pagesMSBI Installation GuideAmit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Improvements To Increase The Efficiency of The Alphazero Algorithm: A Case Study in The Game 'Connect 4'Document9 pagesImprovements To Increase The Efficiency of The Alphazero Algorithm: A Case Study in The Game 'Connect 4'Lam Mai NgocNo ratings yet

- New Installation Procedures - 2Document156 pagesNew Installation Procedures - 2w00kkk100% (2)

- Terms and Condition PDFDocument2 pagesTerms and Condition PDFSeanmarie CabralesNo ratings yet

- Model:: Powered by CUMMINSDocument4 pagesModel:: Powered by CUMMINSСергейNo ratings yet

- ADSLADSLADSLDocument83 pagesADSLADSLADSLKrishnan Unni GNo ratings yet

- Gps Anti Jammer Gpsdome - Effective Protection Against JammingDocument2 pagesGps Anti Jammer Gpsdome - Effective Protection Against JammingCarlos VillegasNo ratings yet

- People vs. Ulip, G.R. No. L-3455Document1 pagePeople vs. Ulip, G.R. No. L-3455Grace GomezNo ratings yet

- Analytical DataDocument176 pagesAnalytical DataAsep KusnaliNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus: Aurora Pioneers Memorial CollegeDocument9 pagesCourse Syllabus: Aurora Pioneers Memorial CollegeLorisa CenizaNo ratings yet

- Academy Broadcasting Services Managerial MapDocument1 pageAcademy Broadcasting Services Managerial MapAnthony WinklesonNo ratings yet

- Nature of ConversionDocument18 pagesNature of ConversionKiranNo ratings yet

- Nature and Effects of ObligationsDocument5 pagesNature and Effects of ObligationsIan RanilopaNo ratings yet

- Short Term Training Curriculum Handbook: General Duty AssistantDocument49 pagesShort Term Training Curriculum Handbook: General Duty AssistantASHISH BARAWALNo ratings yet

- Resume Ajeet KumarDocument2 pagesResume Ajeet KumarEr Suraj KumarNo ratings yet

- Gary Mole and Glacial Energy FraudDocument18 pagesGary Mole and Glacial Energy Fraudskyy22990% (1)

- Programme Report Light The SparkDocument17 pagesProgramme Report Light The SparkAbhishek Mishra100% (1)

- Pig PDFDocument74 pagesPig PDFNasron NasirNo ratings yet

- Lister LRM & SRM 1-2-3 Manual and Parts List - Lister - Canal WorldDocument4 pagesLister LRM & SRM 1-2-3 Manual and Parts List - Lister - Canal Worldcountry boyNo ratings yet

- Okuma Osp5000Document2 pagesOkuma Osp5000Zoran VujadinovicNo ratings yet

- Haryana Retial GarmentsDocument8 pagesHaryana Retial Garmentssudesh.samastNo ratings yet

- 3DS MAX SYLLABUSDocument8 pages3DS MAX SYLLABUSKannan RajaNo ratings yet

- Econ Old Test 2Document7 pagesEcon Old Test 2Homer ViningNo ratings yet