Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gendun Chophel

Uploaded by

Namkha NyingpoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gendun Chophel

Uploaded by

Namkha NyingpoCopyright:

Available Formats

Gendun Chophel

http://www.gdqpzhx.com/english/

Gendun Chophel

school

foundation

headmaster

teacher

tibetan

Gendun Chophel

His Early Life

Gendun Chophel was born in 1903 in Sholphang in Rebkong, Amdo. At the age of

fourteen, after having learnt to read and write from his father, he entered the local Drisha

Monastery. Three years later, he enrolled into the 2,500 monk-strong Labrang Tashi Kyil

Monastery. Since a small child, GC had proven himself to be something of a prodigy, reciting

long and complex liturgical texts after hearing them only once.

By the time Gendun Chophel was in Labrang he had earned for himself the reputation of

a master debater; his specialty was in defending positions that in traditional parlance would

have resulted in sure and ruinous defeat: once he took up the Jain position, rejected by

Buddhists, that plants have consciousness and not one monk in the courtyard could prove

him wrong. In the lm, his friend recounts how GC unfailingly beat his opponents through

such tradition-bending eloquence and wit that his every religious baTle inevitably ended

with the witnessing monks erupting in rambunctious laughter: Ho, ho, ho!

Gendun Chophels unorthodoxy was revealed early on even in such benign act as

reading from a scripture. Once, during a routine recitation in the monasterys chamber where some hundreds of monks were

reading from portions of the Buddhas 108-volume cannon, their individual incantations riding, crashing and disappearing in the

over-arching deafening boom, GC was to be observed in a corner reading his text silently, intently.

If he was known for his brilliance, he stood out also for his searing criticisms of the time-honored monastic curriculum. And so

in 1926, GC was forced to leave the Labrang Monastery; in one version Lopez cites the reason to be GCs fondness for making

mechanical toys. Of his expulsion, he writes biTerly in one poem:

Alas! After I had gone elsewhere

Some lamas who can explain nothing

Said that Nechung, king of deeds

Did not permit me to stay due to my excessive pride

Rather than expelling to distant mountain passes, valleys, And towns One who takes pride in studying the textbooks of Rva

and Bse Would it not be beTer to expel to another place Those who take pride in selling meat, beer, and smoke?

In 1927, after a four month-long journey across vast steppes and salt lakes in the company of a large caravan, Gendun Chophel

arrived in Lhasa. There he joined Drepung Monasterys Gomang College and was put under the charge of Geshe Sherab Gyatso, a

leading Gelug scholar of the day. The teacher-disciple relation was to soon become strained; as he had done before, GC showed

liTle restraint in shredding the doctrines inherent in the monastic texts and he was not the one to shy away from arguing with his

teacher even. Frequently the two were interlocked in shouting matches; exasperated, Sherab Gyatso refused to address his student

by name, calling him instead the madman. (The title of Lopezs book derives its cue from this exchange)

GC soon dropped out from the classes. But he was frequently to be seen in the debating courtyard, confounding his opponents,

challenging the best minds, sometimes in disguises, like for instance that of an illiterate Dobdob, that subgroup of burly monks

who in the Western Hip Hop culture would have translated into club bouncers: big of biceps, sparse of words, generous with jabs.

It is incredible for a wiry man whose nickname it was Drisha Skinny, while at his st monastery, that he could take on such a

formidable appearance; a testament to his chameleon streak indeed.

Around that time, Gendun Chophel pursued his another interest: painting. Not long after, he was making a comfortable living

drawing thankgas, boasting of, among his patrons, such stellar names as Phabonga, a leading Gelug lama. Among few of his

illustrations that survive today are portraitures of photographic realism, a far cry from the conventional painting style, which

capture in black and white shades this aristocrat and that lama, a selected few who could aord to be immortalized on paper by the

1 of 8

16/02/2015 16:15

Gendun Chophel

http://www.gdqpzhx.com/english/

brushstrokes of this most unique monk-artist.

Just months shy from obtaining his Geshe Lharampa degree, GC left Drepung.

Gendun Chophels wanderlust had been fueled early on during his encounters at Labrang with an American missionary,

Marion Griebenow, and his family, from whom he may have learnt some English, and about steam engines and airplanes. But it

was in 1934, after he had met Rahula Sankrityanan, a forty year-old Indian scholar and freedom ghter, which GC was nally to

realize his dreams of journeys into distant India and Ceylon, where he was to remain for the next twelve years. While in Tibet, the

two worked on an ambitious project to salvage rare Sanskrit scriptures from monasteries of southern Tibet, an experience that led

GC to lament the disastrous face of Tibetan superstition as observed in the ways in which local believers pocketed away such text

leafs to stu their amulets and adorn their altars.

Tibetan Buddhisms traditional school curriculums made of its students wonderful debaters of copious memory, at times good

investigators into truths adept at Samadhi, but it instilled in them liTle inspiration to write, to contribute in a literary sense. That

impetus, lacking in the certainty of his traditional seTing, GC was to nd in the shifting sea of his physical wandering; his being

equally seized by languages, words, leTers, native as well as foreign, as by what his eyes saw and his mind perceived: about self as

well as about others.

His Literature

Apart from his occasional dabbling in poetry, Gendun Chophel wrote liTle in Tibet. By the time he returned from India twelve

years later, he had authored a staggering number of works: a travelogue, an unnished history book, an erotica literature, a

pilgrimage guidebook; also an English translation of a Tibetan tome on history of Buddhism, Tibetan translations of Indian classics

like Shakuntala, Bhagavad Gita and Ramayana, and the Pali Theravadin cannon, Dhammapada; numerous Tibetan newspaper

articles and essays in English for one Mahabodhi Society Journal. His muse, in short, hit him bad when he was on the road.

It could be that in the cosmopolitan Rahul Sankrityayan, who looked to Indias tradition

as a source for the revitalization of Indian national consciousness, Gendun Chophel had

found a brethren; and in the new country he set foot in, with its classical tradition which had

newly aTracted a Western scholastic aTention and which had become a subject of robust

reinvention by local nationalists, GC found the creative grounds which had eluded him thus

far. As Tsering Shakya writes, (Gendun Chophels) own growing interest in the sources of

Tibetan Buddhist tradition and history would have led him to nd the India of that period

exciting and inspiring.

In coming from Tibet to India in 1937, which the Tibetans looked to as Aryabhumi, land

of the Buddha, Gendun Chophel had exchanged one milieu for another, both tied together by

a history of spiritual and cultural intercourse, but one that had liTle bearing on real

contemporary terms. And so midway into learning Sanskrit in Lhasa thinking it to be the

spoken language in India, GC had to quickly switch to struggling with English when told by

Rahul that Sanskrit had long ago disappeared from regular conversations.

Gendun Chophels most important work by his own estimation is his travel journal, The

Golden Surface, the story of a Cosmopolitans Pilgrimage, his longest too, which in the course of some 611 pages, only half of them

now surviving, dwells upon such subjects as geographical description of India; the origin of its name; customs of its peoples;

identication of owers and trees and how to recognize them; the edicts of King Ashoka as found on stone inscriptions; a general

history of India with emphasis on the Gupta and the Pala dynasties; as well as history of Sri Lanka and the religions of

non-Buddhists: Hindu, Muslim Islam and Theosophy.

In India, Gendun Chophel took up with Maha Bodhi Society, an international Buddhist missionary organization, which made it

possible for him to later visit Ceylon, to learn there about Theravada monks and their philosophy, to write for their journal in

English, and to author a Guide to Holy Places in India, which many describe as the rst example of modern Tibetan literature and

which the society rst helped publish. As could be expected, this book, both in style and in content, diverged sharply from the

traditional pilgrimage guides: Lamyig, a genre in itself in Tibetan literature associated mostly with reincarnated lamas.

If anything, GCs book, sprinkled with ndings by British archeologists, its narrative more conversational than didactic,

dispelled much of the erroneous facts that had shaped the Tibetan view of India and its many pilgrimage sites; In the Portrait of the

Dalai lama, Charles Bell, then British Political ocer who became a close friend of the Great Thirteenth, remembers: The most

striking admission of ignorance came when he asked me, Where is Bengal? We read this and other such names in our books but

we do not know where these countries are.

While earlier chroniclers had made their guide books a stage for displays of miraculous sightings and fantastical stories,

2 of 8

16/02/2015 16:15

Gendun Chophel

http://www.gdqpzhx.com/english/

Gendun Chophel kept it simple and practical: the book, while being a truthful account of a curious mind, carries such useful details

as railway network, train connection points, breakdown of costs; complete with instructions on procuring maps and deciding on

what to eat and where to sleep.

The Earth is Round

GC also wrote articles and essays for The Tibet Mirror, the only newspaper for Tibetan-speaking world produced from

Kalimpong by Tharchin Babu, another Tibetan exposed to Western values and knowledge. He wrote about events that were

unfolding in the greater world, about Hitler and the rise of Nazis, about Gandhi and the Indian freedom struggle, about airplanes,

steam engine and modern science.

And when in 1938, as Lopez writes, Hitler annexed Austria; OTo Hahn produced the rst nuclear ssion of uranium; Howard

Hughes, ying a twin-engine Lockheed, set a new record for the circumvention of the globe; color television was rst

demonstrated; the rst Xerox image was produced, when the rst Superman episode appeared in Action Comics, in that same

year, GC was aTempting to prove to his countrymen that the world was not at.

He wrote detailed articles to that eect, complete with globe illustrations, latitude and longitude and all. Once, GCs former

teacher Geshe Sherab Gyatso passed through CalcuTa on his way to China, and found himself exposed to his former students

critical questioning: Is the earth at or round? When the Geshe defended traditional cosmology according to Buddhist scriptures,

GC dismissed him with these words: Not even a dog, let alone a man will visit you in China if you talk like that! On this score at

least, GC was wrong: the Geshe later went on to assume important positions in Chinese-occupied Tibet.

In one of his articles, GC put forth an argument that U med, or cursive Tibetan script, had evolved from U chen, or block script,

challenging a widely-held belief that the two systems had been founded separately on another ancient Indian script and Sanskrit

respectively. And so he lived out a role that, as Tsering Shayka notes, was also a burden assumed by modern literary innovations in

most societies, whether the new form has emerged as the organic product of changes in a society or as a result of the impact of

colonial rule. In one poem, GC writes:

I have wriTen facts

Unheard of in the Land of Snows.

Because of my poor and ragged appearance

No one is there to heed my words.

By 1938, much had happened inside Tibet. The 13 th Dalai Lama, who had ushered in a period of de facto independence having

wrested it from the inept Qing dynasty and which triggered o events that while placing his country on the cusp of modernity

rendered it vulnerable to internal intrigues and open struggles at the highest echelon, had passed away. In his place had been

enthroned a 14 th Dalai Lama, now three years old, who was siTing over a nation that was drawing further back into its insularity,

making it liTle prepared for the coming Communist Chinese onslaught. Around that time, in his travel book and his articles, GC

was to forewarn about the horrors of colonialism:

It is generally the case that in every kind of worldly custom, the intelligence of Europeans is superior to ours in a thousand

ways. They could easily spin the heads of the peoples of the East and the South, who, honest but nave, had no experience of

anything other than their own countries. And thus they came to many lands, large and small, accompanied by their armies. Their

hearts were lled with only self-interest. The timid peopleswere caught like sheep and taken to the (foreigners) own countries.

With feet and hands shackled in irons and given only enough food to wet their mouths, they were made to perform the most

dicult work until they died. From Africa alone the people thus captured numbered more than one million, and uncountable

numbers of the unusable were put in huge boats and abandoned at sea.

An Unnished History

GCs most famous work is probably his White Annals, an unnished history of Tibet that for once relied more on documented

evidences culled from archival chambers than on half-myths and half-truths of the Tibetan Buddhist version that all but blurred the

real picture of the countrys past. As Hugh Richardson, British Indias political ocer during the 14 th Dalai Lamas time, notes, the

book was the direct result of his discovery during travels abroad that Western scholars possessed evidence about the early history

of Tibet which was unknown to his contemporaries.

GCs White Annals was, in that sense, a more accomplished history book than the later History of Tibet by Shakabpa, which in

its predictable discourse, in the rigidity of its worldview, diered liTle from biographies of earlier important lamas. And it formed

the impetus for the modern sensibility which contemporary exile scholars like Dawa Norbu, Tsering Shakya and Jamyang Norbu

employ in reconstructing our past, in dening our present. So much so that in GCs use of Tibetan manuscripts salvaged from

Dunhuang caves in China some twenty years earlier, which described the might of Tibets imperial dynasties, one can see the seeds

3 of 8

16/02/2015 16:15

Gendun Chophel

http://www.gdqpzhx.com/english/

for the excellent doctorate thesis Dawa Norbu wrote and which he reproduced toward the end of his book Tibet: The Road Ahead.

In the poem that opens his historical work, GC wrote: Through compiling the available ancient writings That set forth dates in a

manner certain and clear I have generated a small degree of courage To measure the dominion and power of the rst Tibetan

Kingdom. The Tibetan army of red-faced bloodthirsty demons, Who pledged their lives with growing courage to The command of

the wrathful Hayagriva Are said to have conquered two thirds of the circle of the Earth.

Around that time GC struck a friendship with Russian Tibetologist, George Roerich, the son of famed artist and poet, Nicholas

Roerich, who had taken up residence in Manali in India; and with him the Tibetan monk collaborated on an English translation of

the monumental history on Buddhism in Tibet, wriTen some ve centuries earlier, called the Blue Annals. It is also likely that

around then GC came into contact with modern styles and tempo in paintings, which he incorporated into the skilled strokes of his

own paintbrush, thus stretching the expanse of his genius, making him as much of an artist as a scholar and a poet.

The poet in GC had been at work from very early days. But while his poetry wriTen in the Labrang followed formalistic

conventions and exaggerated tones, his later works were to reect a sentiment more personalized than practiced, a way of

expressing both subtle and sophisticated, its narrative venturing so far as to incorporate the use of colloquial language. He also

wrote poems in English; Heather Stoddard in her biography comments that in his English poems the inuence of nineteenth

century English Romantics is noticeable in the vocabulary and style. In his essays and his poetry, GC championed social reforms

and criticized his peoples blind superstition, as evident in a poem widely quoted even today:

All that is old is proclaimed as the work of gods All that is new conjured by the devil Wonders are thought to be bad omens

This is the tradition of the land of the Dharma.

Like in the novels of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, particularly his Love in the Time of Cholera and Memories of My Melancholic

Whores, in which his protagonists straddle the deceptive grounds of lust and love, seeking a life with which to reect their art, the

sex more often than not paid for, so too it seems GC spent his CalcuTa days in uTer lasciviousness, a part of him looking for that

experience with which to esh out his Treatise on Passion, a book inspired by Kamasutra.

In lyrical prose, his erotic manual, translated by Jerey Hopkins into English as Tibetan Arts of Love: Sex, Orgasm and Spiritual

Healings, details the subtle nuances and multifarious aspects of kissing, biting, touching, scratching, penetrating, the types of

foreplays and after, with such knowingness that it would have left bewildered even the most notorious layman out on his nightly

expedition of climbing onto a rooftop and slipping into an unsuspecting womans sheepskin blanket, missionary style. As GC

writes:

With small shame for myself and great faith in women I am the kind who chooses evil and abandons good. For some time I

have not had the vows in my head But recently I stopped the pretense in my bowels.

The books instructions on heightened sexual pleasure nds its subtext in the spiritual aspirations of Tantric Buddhisms

sixty-four arts of love, which seek to generate through orgasm a more subtle and powerful level of consciousness; in the mad rush

of orgasm, in its nality, one is revealed, subconsciously, the dynamism of spiritual path. Treatise was the only second such

manual to appear in the history of Tibetan literature, the rst having been composed by the famous Nyingma scholar, MiPham.

Making a point of dierence between the two works, GC continues:

The venerable Mipham wrote from what he studied The promiscuous Chophel wrote from what he experienced The dierence

in the power of their blessings Will be understood when a passionate man and woman put Them into practice.

Going Back to the Roots

Gendun Chophels writings, as most commentators observe, are marked by two recurring elements: biTerness and poignancy.

In describing the land of Aryans to his audience back home, much of his breath was wasted in undoing misconceptions bordering

on fanaticism; in talking about the roundness of the earth, he was charged with rebelling against Buddhas words; in reclaiming the

militaristic glory of his nations past, before Tibetan Buddhism mind-shepherded an entire populace to eschew its defense instincts,

he risked humiliating his very history. For a writer, he was in a worst place possible. For the community of his readers, disapproval

came more naturally than praise, ridicule than respect.

But then paradoxically, as Tsering Shakya says, What is noteworthy about Gendun Chophels work is that his interests were

primarily conned to the examination and exploration of his own cultural tradition. Despite the fact that he had acquired a good

knowledge of English and was able to compose poems and write articles in that language, there is no evidence that he showed

much interest in Western literature. Gendun Chophels interest lay in the sources of his own tradition rather than in a search for

new elds, just as his studies of Sanskrit and Pali were a part of his research into the original sources of the Tibetan canon. His

focus on authenticity and on the roots of Tibetan culture to some degree shows an element of nationalist thought, of an eort to

4 of 8

16/02/2015 16:15

Gendun Chophel

http://www.gdqpzhx.com/english/

construct a new understanding of the past.

And so it is Ting that his last known work, also most explosive, was his most elemental, a journey to the very beginning: a

treatise about that most authoritative tenet of Tibetan Buddhism, Nagarjunas philosophy of Middle Way. It is said Gendun

Chophel wrote a core part of this text and the rest he dictated to one of his disciples, a Nyingma monk, which added another

dimension to the resulting controversy. Some accounts say GC dictated parts of this book in a series of drunken slur; one anecdote

has it that GC, while completely inebriated once, laid out with incredible lucidity the interpretation of Madhyamaka.

The Adornment was wriTen either before Gendun Chophel was put in prison in 1946, or after he was released three years later

in 1949. It immediately sparked a controversy that is yet to subside even to this day, provoking refutations from the best minds of

Gelug scholasticism, among them a close Geshe colleague of Trijang Rinpoche: their aTacks targeting not only GCs philosophy,

but his intelligence, his integrity even.

The man, if anything, was a true man of the leTers. When he returned to Tibet, after his twelve years abroad, a bulk of his

belongings comprised of several boxes of notes, some scribbled on cigareTe wrappers. As GCs monk companion remarks in the

lm, Angry Monk, he would always be writing something. Even at a train station, surrounded by the bustle and chaos of all that

went by, he would be looking at things, people, and then joTing something down on a paper. The boxes had disappeared from his

house when Gendun Chophel was released; some say the Lhasa government had handed them over to the British counterpart,

perhaps as a token of thanks for turning in a man suspected of involvement with Russian Communist expansionists.

Books by Gendun Chophel

UGG

By Gendun Chophel

Translation by Toni Huber

The creative and controversial Tibetan intellectual Amdo Gendun Chophel (1903-1951) composed his guide to India during the 1930's

while visitting many of the ancient sites of Indian Buddhism, which had only recently been the object of archaeological rediscovery and

modern religious revival.

His work offered traditionally minded pilgrims from the remote Tibetan highlands clear instructions on the correct identification of

vaporizer

authentic Buddhist sites, as well as unique practical guide for using the Indian rail system. The Guide to India is one of the first works of

Modern Tibetan Literature and was to become the most used manual contemporary Tibetan pilgrimage.

Tibetan Arts of Love

Sex, Orgasm and Spiritual Healing

Author(s) :

Gedun Chopel and Hopkins, Jeffrey and Dorje Yuthok

Synopsis:

A Karma Sutra in the Tibetan tradition, containing the classic Indian 64 arts of love and the sexual methods for attaining bliss, harmony,

love and joy. It also gives the methods of increasing the experience of bliss and emptiness for yogis who are meditating according to the

two highest tantras.

The book includes a complete translation of the Treatise on Passion by the highly controversial Gedun Chopel, as well as an account of

his fascinating life story. An over-arching focus is placed on sexual ecstasy as a door to spiritual experience of fundamental mind; the

sky experience of the mind of clear light pervades the scintillating descriptions of erotic acts.

5 of 8

16/02/2015 16:15

Gendun Chophel

http://www.gdqpzhx.com/english/

Author(s) : Gedun Chopel

Synopsis:

An English translation of the classic verses on the Dharma set side by side with the Tibetan text. The outstanding Tibetan scholar Gedun

Chophel translated this classic work from the Pali into Tibetan, and here it has been translated into English by the staff of Dharma

Publishing with the Tibetan text alongside.

Poems by Gedun Choephel

Manasarovar

By Gendun Choephel

In the times now long forgoTen

In the night of other ages,

When things were not as they now are

Lay the earth a lifeless body,

Cold and hard and all unyielding,

Like a maid in dreamless slumber,

Untouched by lifes budding springmood,

Ere the glow of sun light calls her.

And the sky looked down and saw her.

Gently then in stealth descending,

In the rose of early twilight

Stooped and kissed her in her slumber.

And behold her young heart heaving,

Throbbed her pulse, her eyelids opened

And those eyes, all lled with wonder

Shed the hot tears of her being.

Thus was born this lake Himalayan,

Mother of the holy Ganga.

II

Mountain-wave, mystic and dreamy,

By thy shore does stand a maiden

And the rhythm of thy water

Blends into her burning bosom,

Stands she motionless and gazing,

Knows not where her ocks are staying.

The young hunter aims his arrow,

And, behold, he sees thy water,

And no more sees he the roebuck

Slacks the bowstring, ees the quarry.

When the sun is golden glory

Sheds his aureole oer thy surface, -

Standst thou like the shrine Campaca

But the white dreamrays of moon-light

6 of 8

16/02/2015 16:15

Gendun Chophel

http://www.gdqpzhx.com/english/

Veils thee in a garb of silver,

In the rope of Milarepa.

Rebkong

By Gendun Choephel

My feet are wandering neath the alien star,

My native land, - the road is far and long.

Yet the same light of Venus and Mars

Falls on the small green valley of Rebkong.

Rebkong, - I left thee and my heart behind,

My boyhoods dusty plays, - in far Tibet.

Karma, that restless stallion made of wind,

In tossing me; where will it land me yet?

Like autumn cloud I oat, soon, there, soon here,

I know not what the eeting moons may bring.

Here in this land of roses, fair Kashmir,

My years are closing around me like a ring.

Fate sternly sits at Destinys hard loom

And irrevoked her tangled paTern weaves

The winds are blowing around my fathers tomb

And I but dream of those still summer eves,

When - child - I listened to my mothers voice,

Whose stories made my youthful heart rejoice.

So far, so far I may not see those graves.

Ah, friend, these separation pangs are sore.

My heart is thrown upon the ocean waves

Where shall at last reach a peaceful shore?

Ive drunk of holy Gangas glistening wave,

Ive sat beneath the sacred Bodhi tree,

Whose leaves the wanderers weary spirit lave.

Thou sacred land of Ind, I honour thee,

But, oh, that like valley of Rebkong,

The sylvan brook which ows that vale along.

Milarepas Reply

By Gendun Choephel

The earth and sky held counsel one night,

And called their messengers from northern height.

And came they, the storm ends, the bleak and the cold,

They, who the stormwinds in grim ngers hold.

They swept oer the earth, and then they called forth

That glistning maid from the far Polar North

In white trailing robe, the Queen of the Snow

And she sent her uTring plumed children below.

7 of 8

16/02/2015 16:15

Gendun Chophel

http://www.gdqpzhx.com/english/

And downward they ew in wile, whirling showers,

While in black masses hung threatning the sky.

Some were large cruel sharp-stinging owers

Some pierced his chest with a erce-cuTing eye.

Thus stormends, snow and icy frost blending

Came cold and sharply upon him descending.

On his half nude form these shapes did alight.

And tried with his single thin garments to tight.

But Milarepa, the Snow-mountains child

Feared no their onslaughts, so cruel and wild.

Though they aTacked him most ercely and grim,

He only smiled - they had no power over him.

Oh Where?

By Gendun Choephel

A city there is which lone does stand

In ruins mid bamboo trees

Hot blows the burning desert sand

Where dry shrubs sigh on thirsting land,

Where monkeys cry, and with these

Joins the shrill cry of the jungle cock

Where a maiden drives her scaTered ock

To the tunes of the ancient lay.

Where an ox cart moves on its lazy way

Ad the halts for shade bneath a juTing rock;

Oh, City, where is the day,

When on thy golden Throne sat Kings

Who held the Sceptre high in this place?

Hark, heareth thou Times eet wings?

Copyright Gdqpzhx.com All rights reserved E-mail:sndz009@163.com

8 of 8

16/02/2015 16:15

You might also like

- Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist SaintFrom EverandRenunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist SaintNo ratings yet

- In the Forest of Faded Wisdom: 104 Poems by Gendun Chopel, a Bilingual EditionFrom EverandIn the Forest of Faded Wisdom: 104 Poems by Gendun Chopel, a Bilingual EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Rgyalrong Conservation and Change: Social Change On the Margins of TibetFrom EverandRgyalrong Conservation and Change: Social Change On the Margins of TibetNo ratings yet

- Khyen Tse LineageDocument1 pageKhyen Tse LineageesnekoNo ratings yet

- A Garland of Gold: The Early Kagyu Masters in India and TibetFrom EverandA Garland of Gold: The Early Kagyu Masters in India and TibetNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness and Awareness - Tai Situ RinpocheDocument1 pageMindfulness and Awareness - Tai Situ Rinpocheacrxavier2082No ratings yet

- Introduction to Bodhicaryavatara by Shangpa RinpocheDocument10 pagesIntroduction to Bodhicaryavatara by Shangpa RinpocheguscribedNo ratings yet

- Blue Cliff Record Case 11 - John TarrantDocument3 pagesBlue Cliff Record Case 11 - John TarrantPapy RysNo ratings yet

- Helping Yourself and Others Die Happily: Instructions and Practices for the Time of Death EbookFrom EverandHelping Yourself and Others Die Happily: Instructions and Practices for the Time of Death EbookNo ratings yet

- What Changes and What Doesn't An Interview With Dzongsar Khyentse RinpocheDocument3 pagesWhat Changes and What Doesn't An Interview With Dzongsar Khyentse RinpocheDtng FcbkNo ratings yet

- Six Paramitas - Tai Situ RinpocheDocument16 pagesSix Paramitas - Tai Situ Rinpochephoenix1220No ratings yet

- Blue Cliff Record Case 2 - John TarrantDocument3 pagesBlue Cliff Record Case 2 - John TarrantPapy RysNo ratings yet

- Histories of Tibet: Essays in Honor of Leonard W. J. van der KuijpFrom EverandHistories of Tibet: Essays in Honor of Leonard W. J. van der KuijpNo ratings yet

- Life of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi LodröDocument18 pagesLife of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi LodröAndriy VoronovNo ratings yet

- Nagarjuna Teaching Booklet EnglishDocument65 pagesNagarjuna Teaching Booklet EnglishsonamNo ratings yet

- Sharing the Same Heart: Parents, children, and our inherent essenceFrom EverandSharing the Same Heart: Parents, children, and our inherent essenceNo ratings yet

- The Path to EnlightenmentDocument32 pagesThe Path to EnlightenmentMaureen100% (1)

- Vdocuments - MX The Words of My Perfect Teacher by Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche SanDocument73 pagesVdocuments - MX The Words of My Perfect Teacher by Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche SanTempa JikmeNo ratings yet

- Mangalashribhuti LNNDocument18 pagesMangalashribhuti LNNhenricat39100% (1)

- The Vow and Aspiration of Mahamudra: Including the Pith Instructions of Mahamudra: Including the Pith Instructions of Mahamudra by TilopaFrom EverandThe Vow and Aspiration of Mahamudra: Including the Pith Instructions of Mahamudra: Including the Pith Instructions of Mahamudra by TilopaNo ratings yet

- Mountain Dharma, The Ocean of Definitive MeaningDocument549 pagesMountain Dharma, The Ocean of Definitive MeaningAron DavidNo ratings yet

- Brief Biography of Patrul RinpocheDocument4 pagesBrief Biography of Patrul RinpocheBecze IstvánNo ratings yet

- Hevajra Tantra WikiDocument5 pagesHevajra Tantra WikiCarlos GreeneNo ratings yet

- Buddhadharma Without CredentialsDocument2 pagesBuddhadharma Without CredentialsShyonnu100% (1)

- Always Remembering: Heartfelt Advice for Your Entire LifeFrom EverandAlways Remembering: Heartfelt Advice for Your Entire LifeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Heart Advicefor Practicing Dharmain Daily LifeDocument9 pagesHeart Advicefor Practicing Dharmain Daily Lifevivekgandhi7k7No ratings yet

- Golden Light Sutra Chapter 3Document3 pagesGolden Light Sutra Chapter 3Jessica100% (1)

- Jamgon Kongtrul The Great: A Short BiographyDocument4 pagesJamgon Kongtrul The Great: A Short BiographyalbertmelondiNo ratings yet

- Biography of Jamgön Ju MiphamDocument6 pagesBiography of Jamgön Ju MiphamBLhundrupNo ratings yet

- Big HopeDocument2 pagesBig HopeShenphen Ozer0% (1)

- Biography of H.H Dudjom RinpocheDocument4 pagesBiography of H.H Dudjom RinpocheTashi DubjurNo ratings yet

- Distinguishing The Views and Philosophie PDFDocument45 pagesDistinguishing The Views and Philosophie PDFJason FranklinNo ratings yet

- The Four Immeasurables by Dilgo Khyentse RPCDocument1 pageThe Four Immeasurables by Dilgo Khyentse RPCkimong123No ratings yet

- Dzongsar Khyentse On Sex With The Lama Updated July 2018Document25 pagesDzongsar Khyentse On Sex With The Lama Updated July 2018Lungtok Tenzin100% (2)

- Nurturing Compassion: Teachings from the First Visit to EuropeFrom EverandNurturing Compassion: Teachings from the First Visit to EuropeNo ratings yet

- + Zhang WorksDocument267 pages+ Zhang Worksheinzelmann2No ratings yet

- Explanation of Atisha's Lamp For The Path To Enlightenment Part 1Document12 pagesExplanation of Atisha's Lamp For The Path To Enlightenment Part 1albertmelondiNo ratings yet

- KI PathAndGrounds Delighting DrapaSedrupDocument38 pagesKI PathAndGrounds Delighting DrapaSedrupjiashengroxNo ratings yet

- Available Truth: Excursions into Buddhist Wisdom and the Natural WorldFrom EverandAvailable Truth: Excursions into Buddhist Wisdom and the Natural WorldNo ratings yet

- Ornament to Beautify the Three Appearances: The Mahayana Preliminary Practices of the Sakya Lamdré TraditionFrom EverandOrnament to Beautify the Three Appearances: The Mahayana Preliminary Practices of the Sakya Lamdré TraditionNo ratings yet

- A Feast For Scholars: The Life and Works of Sle Lung Bzhad Pa'i Rdo Rje - Dr. Cameron BaileyDocument279 pagesA Feast For Scholars: The Life and Works of Sle Lung Bzhad Pa'i Rdo Rje - Dr. Cameron BaileyTomNo ratings yet

- The Tradition of Everlasting Bön: Five Key Texts on Scripture, Tantra, and the Great PerfectionFrom EverandThe Tradition of Everlasting Bön: Five Key Texts on Scripture, Tantra, and the Great PerfectionJ. F. Marc de JardinsNo ratings yet

- Rumtek Monastery ArchitectureDocument10 pagesRumtek Monastery ArchitectureAnirudh MalpaniNo ratings yet

- Dodrupchen Jikmé Tenpé Nyima's Teachings on Illusory OfferingsDocument6 pagesDodrupchen Jikmé Tenpé Nyima's Teachings on Illusory OfferingsKarma Y100% (1)

- A Letter From Lama Tharchin Rinpoche To The Vajrayana Foundation SanghaDocument4 pagesA Letter From Lama Tharchin Rinpoche To The Vajrayana Foundation SanghaalbertmelondiNo ratings yet

- Autobiography HH Gyalwang Drukpa RinpocheDocument65 pagesAutobiography HH Gyalwang Drukpa RinpocheOxyak100% (1)

- A Short Life History of HH Dudjom Rinpoche II EnglishDocument5 pagesA Short Life History of HH Dudjom Rinpoche II EnglishJoãoPereiraNo ratings yet

- The Life of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi LodröDocument19 pagesThe Life of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi LodröricojimiNo ratings yet

- Complete Nyingma Tradition From Sutra To Tobden Dorje 0 Gyurme Dorje 0 Lama TharchinDocument3 pagesComplete Nyingma Tradition From Sutra To Tobden Dorje 0 Gyurme Dorje 0 Lama TharchinDoron SabariNo ratings yet

- Blue-Pancake - Trungpa, C Hogyam Rimpoche PDFDocument2 pagesBlue-Pancake - Trungpa, C Hogyam Rimpoche PDFDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Should Yoga Be Part of NHS Care? - Healthcare Professionals Network - The GuardianDocument3 pagesShould Yoga Be Part of NHS Care? - Healthcare Professionals Network - The GuardianLamaCNo ratings yet

- Why Capitalism Has Turned Us Into NarcissistsDocument3 pagesWhy Capitalism Has Turned Us Into NarcissistsNamkha Nyingpo100% (1)

- SSSHHH! How The Cult of Quiet Can Chang... R Life - Life and Style - The Guardian PDFDocument4 pagesSSSHHH! How The Cult of Quiet Can Chang... R Life - Life and Style - The Guardian PDFNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Treasury Proposal May Fine Tax Evaders Up To 200% of Amount Owed - World News - The GuardianDocument2 pagesTreasury Proposal May Fine Tax Evaders Up To 200% of Amount Owed - World News - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- The 13 Impossible Crises That Humanity Now Faces - George Monbiot - Opinion - The GuardianDocument3 pagesThe 13 Impossible Crises That Humanity Now Faces - George Monbiot - Opinion - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- News, Sport and Opinion From The Guardian's UK Edition - The GuardianDocument3 pagesNews, Sport and Opinion From The Guardian's UK Edition - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Stella Grey: Shacking Up in Mid-Life Makes Me Feel 28 Again - Life and Style - The GuardianDocument5 pagesStella Grey: Shacking Up in Mid-Life Makes Me Feel 28 Again - Life and Style - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Sleep 'Resets' Brain Connections Crucial For Memory and Learning, Study Reveals - Science - The GuardianDocument3 pagesSleep 'Resets' Brain Connections Crucial For Memory and Learning, Study Reveals - Science - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- The Anthropocene Epoch: Scientists Declare Dawn of Human-Influenced Age - Science - The GuardianDocument4 pagesThe Anthropocene Epoch: Scientists Declare Dawn of Human-Influenced Age - Science - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Childhood Concussion Linked To Lifelong Health and Social Problems - Science - The GuardianDocument3 pagesChildhood Concussion Linked To Lifelong Health and Social Problems - Science - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- More Than 30 Fake UK Universities Closed by Watchdog - Education - The GuardianDocument2 pagesMore Than 30 Fake UK Universities Closed by Watchdog - Education - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- How Do People Die From Cancer? You Asked Google - Here's The Answer - Ranjana Srivastava - Opinion - The GuardianDocument4 pagesHow Do People Die From Cancer? You Asked Google - Here's The Answer - Ranjana Srivastava - Opinion - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Fat Girls Do Yoga Too - Life and Style - The GuardianDocument4 pagesFat Girls Do Yoga Too - Life and Style - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Lost Cities #7: How Nasa Technology Uncovered The 'Megacity' of Angkor - Cities - The GuardianDocument4 pagesLost Cities #7: How Nasa Technology Uncovered The 'Megacity' of Angkor - Cities - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Gut Reaction: The Surprising Power of Microbes - Ed Yong - Science - The GuardianDocument10 pagesGut Reaction: The Surprising Power of Microbes - Ed Yong - Science - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- How To Stop Wasting Women's Talents: Overcome Our Fixation With Youth - Margaret Hodge - Opinion - The GuardianDocument3 pagesHow To Stop Wasting Women's Talents: Overcome Our Fixation With Youth - Margaret Hodge - Opinion - The GuardianlamacarolineNo ratings yet

- Germaine Greer's Archive: Digging Up Digital Treasure From The Floppy Disks - Books - The GuardianDocument5 pagesGermaine Greer's Archive: Digging Up Digital Treasure From The Floppy Disks - Books - The GuardianlamacarolineNo ratings yet

- DK, Kalachakra, ShambhalaDocument12 pagesDK, Kalachakra, ShambhalaStephane CholletNo ratings yet

- Experience: I See Words As Colours - Life and Style - The GuardianDocument2 pagesExperience: I See Words As Colours - Life and Style - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- A Moment That Changed Me: Group Therapy Stopped Me Falling For Versions of My Dad - Eleanor Moran - Opinion - The Guardian PDFDocument3 pagesA Moment That Changed Me: Group Therapy Stopped Me Falling For Versions of My Dad - Eleanor Moran - Opinion - The Guardian PDFNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Bishop of Grantham First C of E Bishop ... Lationship - World News - The Guardian PDFDocument4 pagesBishop of Grantham First C of E Bishop ... Lationship - World News - The Guardian PDFNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Don't Floss, Peel Veg or Wash Your Jeans: 40 Things You Can Stop Doing Right Now - Life and Style - The GuardianDocument4 pagesDon't Floss, Peel Veg or Wash Your Jeans: 40 Things You Can Stop Doing Right Now - Life and Style - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- 8 Blunt Truths About Becoming A Yoga Instructor. Rachael Carlevale - Elephant JournalDocument19 pages8 Blunt Truths About Becoming A Yoga Instructor. Rachael Carlevale - Elephant JournallamacarolineNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Spanish Citizenship and Permanent Residence - Visas & Permits - Expatica SpainDocument18 pagesA Guide To Spanish Citizenship and Permanent Residence - Visas & Permits - Expatica SpainNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- It Hits You Over The Head': Can I Survive My Midlife Crisis? - Life and Style - The GuardianDocument5 pagesIt Hits You Over The Head': Can I Survive My Midlife Crisis? - Life and Style - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Season of The Witch: Why Young Women Are Flocking To The Ancient Craft - World News - The GuardianDocument4 pagesSeason of The Witch: Why Young Women Are Flocking To The Ancient Craft - World News - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- 8 Signs You're in A Strong Relationship - Even If It Doesn't Feel Like It - The IndependentDocument8 pages8 Signs You're in A Strong Relationship - Even If It Doesn't Feel Like It - The IndependentNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Angkor Anger - Naked Western Tourists Offend Cambodians at Sacred Temples - World News - The GuardianDocument3 pagesAngkor Anger - Naked Western Tourists Offend Cambodians at Sacred Temples - World News - The GuardianNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

- Dharma Wheel - View Topic - Sakya POV On The Origin of The Cakrasamvara TantrasDocument20 pagesDharma Wheel - View Topic - Sakya POV On The Origin of The Cakrasamvara TantrasNamkha NyingpoNo ratings yet

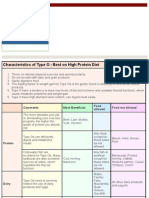

- Blood Type Diet - Type O - DrLam® - Body. Mind. Nutrition®Document5 pagesBlood Type Diet - Type O - DrLam® - Body. Mind. Nutrition®Namkha Nyingpo100% (2)

- Topic 8 - Managing Early Growth of The New VentureDocument11 pagesTopic 8 - Managing Early Growth of The New VentureMohamad Amirul Azry Chow100% (3)

- Global Finance - Introduction ADocument268 pagesGlobal Finance - Introduction AfirebirdshockwaveNo ratings yet

- Aromatic Saturation Catalysts: CRI's Nickel Catalysts KL6564, KL6565, KL6515, KL6516Document2 pagesAromatic Saturation Catalysts: CRI's Nickel Catalysts KL6564, KL6565, KL6515, KL6516Ahmed SaidNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 04-10-2013Document37 pagesTimes Leader 04-10-2013The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- Checklist For HR Audit Policy and ProceduresDocument3 pagesChecklist For HR Audit Policy and ProcedureskrovvidiprasadaraoNo ratings yet

- Challan Form OEC App Fee 500 PDFDocument1 pageChallan Form OEC App Fee 500 PDFsaleem_hazim100% (1)

- Annex-4-JDVP Certificate of Learners MasteryDocument1 pageAnnex-4-JDVP Certificate of Learners MasteryZINA ARRDEE ALCANTARANo ratings yet

- Volatility Clustering, Leverage Effects and Risk-Return Trade-Off in The Nigerian Stock MarketDocument14 pagesVolatility Clustering, Leverage Effects and Risk-Return Trade-Off in The Nigerian Stock MarketrehanbtariqNo ratings yet

- Mendoza CasesDocument66 pagesMendoza Casespoiuytrewq9115No ratings yet

- Oral READING BlankDocument2 pagesOral READING Blanknilda aleraNo ratings yet

- David Freemantle - What Customers Like About You - Adding Emotional Value For Service Excellence and Competitive Advantage-Nicholas Brealey Publishing (1999)Document312 pagesDavid Freemantle - What Customers Like About You - Adding Emotional Value For Service Excellence and Competitive Advantage-Nicholas Brealey Publishing (1999)Hillary Pimentel LimaNo ratings yet

- Promotion From Associate Professor To ProfessorDocument21 pagesPromotion From Associate Professor To ProfessorKamal KishoreNo ratings yet

- HDFC Bank's Organizational Profile and BackgroundDocument72 pagesHDFC Bank's Organizational Profile and Backgroundrohitkh28No ratings yet

- Research Paper 1 Eng Lang StudiesDocument4 pagesResearch Paper 1 Eng Lang Studiessastra damarNo ratings yet

- GUCR Elections Information 2017-2018Document10 pagesGUCR Elections Information 2017-2018Alexandra WilliamsNo ratings yet

- CL Commands IVDocument626 pagesCL Commands IVapi-3800226100% (2)

- Wave of WisdomDocument104 pagesWave of WisdomRasika Kesava100% (1)

- Society and CultureDocument40 pagesSociety and CultureRichard AbellaNo ratings yet

- Essay Sustainable Development GoalsDocument6 pagesEssay Sustainable Development GoalsBima Dwi Nur Aziz100% (1)

- GST Project ReportDocument29 pagesGST Project ReportHENA KHANNo ratings yet

- Limiting and Excess Reactants Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesLimiting and Excess Reactants Lesson Planapi-316338270100% (3)

- Minotaur Transformation by LionWarrior (Script)Document7 pagesMinotaur Transformation by LionWarrior (Script)Arnt van HeldenNo ratings yet

- Brinker Insider Trading SuitDocument5 pagesBrinker Insider Trading SuitDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Method Statement For Wall Panels InstallationDocument11 pagesMethod Statement For Wall Panels InstallationChristos LoutrakisNo ratings yet

- Plusnet Cancellation FormDocument2 pagesPlusnet Cancellation FormJoJo GunnellNo ratings yet

- Restructuring ScenariosDocument57 pagesRestructuring ScenariosEmir KarabegovićNo ratings yet

- Cub Cadet 1650 PDFDocument46 pagesCub Cadet 1650 PDFkbrckac33% (3)

- Dalit LiteratureDocument16 pagesDalit LiteratureVeena R NNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Consent Form: Tetanus, Diphtheria / Inactivated Polio Vaccine (DTP) & Meningococcal ACWY (Men ACWY)Document2 pagesVaccination Consent Form: Tetanus, Diphtheria / Inactivated Polio Vaccine (DTP) & Meningococcal ACWY (Men ACWY)meghaliNo ratings yet

- OF Ministry Road Transport Highways (Road Safety Cell) : TH THDocument3 pagesOF Ministry Road Transport Highways (Road Safety Cell) : TH THAryann Gupta100% (1)