Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3.the Nature of Applied Ethics

Uploaded by

RicardoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3.the Nature of Applied Ethics

Uploaded by

RicardoCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Th N t

f A l i d Ethi

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

Th t

" l i d thi"

d it

" t i l

thi"

it

i h

1970

h

h i l h

d th

d i

b

t

dd

i

l

bl

i

it

di

f i l

thi ( i l l

d i l thi

d b i

thi) P i t

l th

d

bti

t h i

th

t

ti

fh

d i l

bjt i

h

i

i

f f t i

ti

acceptable risk in the workplace the legal enforcement of morality civil disobedi

ence unjust war and the privacy of information

H i t i l

D i t th

t ii

f th t

" l i d thi"

i

t i

tht f

t

bjt

tt

b t d t

i t ti

F

l libti

t

blih

controversial opinions engage in civil disobedience commit suicide and choose

one's religious viewpoint are matters of perennial interest as are questions of unjust

wars and the moral status of animals Although moral philosophers have long

d i d th

bl

it i

bl th

tht

j

h i l h

t h h

t th h i t

f

l h i l h h d l d

thd f

lid

thi

M l

h i l h

h

tditill f l t d t h i

f th i h t h

d

d th i t

tht

t t i th

t

lt

A

til

i

i

id f thi t h t i l

lit it i

ll h

hth

d if

h

th

i t b

lid t

t

bli

li

ttl

l

bl

d d

t

i

t i l

It is not obvious that applied ethics is the offspring of or even dependent upon

general moral philosophy Its early successes in the 1970s owed more to arguments

directed at pressing and emerging moral problems in society than to traditional theor

i

f thi M

idiidl i l

h i l h i l

d t h l i l thi

litil

th

d th

f i

ildi

dii

b i

i i

d itifi

h d d d th

i

Th

idiidl

f d l

fftd b

i th

id

it

di i d i i d l l i b t i

il

lit

d

i

f

f b

dijti

d i t d t l b l

Th i

i d b iil

iht

' iht

i l i h t th

t th

i t l

1

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

t

d th i h t

f i

d th

t l l ill ft i l d d

thil

issues that stimulated the imagination of philosophers and nonphilosophers alike

(A volume that nicely illustrates the state of one area of interdisciplinary ethical

inquiry around 1970 is the massive compendium on research involving human

bjt

titld Experimentation with Human Beings [ K t 1972])

I th l t 1960

d

l 1970 h i l h

i i l

it

t t

ith

l f

th d i i l i

h

i t t d i

l

bl

ldi

th

f th h l t h

f i

l

b i

i i

d th

il

d b

h i l

i

P h

th

t i f l t i l f l d i th d l t

f

hl

l litt

i

l i d thi

l

d

l h i l h

M

bl

f

applied ethics have since been framed in the vocabularies of these two disciplines

This is not surprising since moral philosophy and law have common concerns over

matters of basic social importance and share various principles requirements and

iti

f id

L

i i

t th

bli'

f

t l t i

lit i t

liit

il

idli

d

ti

df tilti

i h t

f

ff

C

l

i

til

h

idd

d t

db i

t i l tht

i f l t i l i ll

f

l i d thi

D i

th 1970

d

l 1980

b

f h i l h

b

t fhi

their careers around interests in applied ethics an almost unprecedented develop

ment in a profession generally skeptical that "applied ethics" was either a scholarly

enterprise or had a future in the university The late 1970s and early 1980s saw

th

bliti

f

l b k d t d t h i l h i l t t t

f

bjt

l i d thi

Vitll

b k

blihd i

l i d thi

i t th l t

1970 h d b

id t i l l

th th

i t

f

l

i i l

h i l h i l t h i

Thi

itti

h d

idl i th l t 1970

d

1980

Problems of Definition

M

h i l h

h

i d

l i d thi

th t t t t i l t

ith

l

l

lt h i

ith th

l f

li

til

bl

Th

th

t

d

l i

t l tht

b

d t

i

th

l

bl

H

it i t d

ll

td tht

t i h t f d

tt

til j d t

i

ibl b

l ith t

l t h i

t

l

l i i l

( h

"O

ht

t t

t t

l

t th

d f t h " "O

ht t k

i " "O

ought not to inflict harm or risk of harm;" "One ought to treat people fairly and

with equal respect;" and "One ought to respect the autonomy of others") This s

the socalled gap between theory and practice Theory and principles must it

b

l t d i

b

di

f iht

ti

i i l

dt

i t i l

i

d th lik B t i

il

hih

()? Thi

ti h l

h " l i d thi" i

difflt

ti t

d t d

d df

A d i l

it

d b t f l tht

l i d thi i b t d f d

th

li

ti

f

l thil t h i

t

til

l

bl

( h l

th d f i t i

l

THE NATURE OF APPLIED ETHICS

ffd

b G t 1982 5 1 2 ) Thi d f i i t i

i

tht

ill

t

recognize it as reflecting either the appropriate method or content of applied ethics

A weaker and more defensible view is that "applied ethics" refers to any use

of philosophical methods to treat moral problems practices and policies in the

f i

t h l

t

d th lik Thi b d

k

i t t t th l

f

l t h i

i i l

d d

t i i t

b l l i

th

l It

b th

t

d t d i

f th t

ithi th

f i

f h i l h

b t it

ld b i d

tid

h i l h

flti

i i f i t diili

bi

A d i f f t bi i f d i th id t h t " l i d t h i " i

ith

"professional ethics" Problems such as the allocation of scarce medical resources

unjust wars abortion conflicts of interest in surrogate decisionmaking hate

crimes pornography war and terrorism whistleblowing the entrapment of public

ffiil

i t t i l

jti

h

i l

d th

fidtilit

f

t i f t i

t d b d

f i l

d t

t ll

t i

i th

d i

f

l i d thi

Th

t l

ti

b t th

t

f" l i d

thi"

l d t

idti

f b t h th

t t

d th

thd f

l i d thi

Problems of Moral Content

Th

i f l t i l t

f

h

d i th l i t t

th

it

f

t t i

l i d thi

i t l

t

t l

t

d

i d i t l t l

t Th

t i

fit

f h i d f th

l i

f

f i l

thi

b t th

b

l i d t th

h

i t i t t i l

d

thi

f ll t

Th fit d f d

thi d i d f

f i l

i t i t t i l

ti

t d d

Th

d

iti

tht

t i

tti

f

l i d thi

l

d

i jtifiti

b

external standards such as those of public opinion law the common morality

religious ethics and philosophical ethics The third claims that distinct forms of

t i l thi internal t

f i

d ititti

t h l

d l

i f l d b b d

( t l )

l t l

f

k

Internalism

S

h i l h

h

i t i d tht tblihd

ti

id th

i

f

t i l thi I f l t i l i thi l i t t

i Aldi M l t '

f

"practice" to designate a cooperative arrangement in pursuit of goods that are

internal to a structured communal life He holds that "goods internal to a practice"

such as those found in the professions are achievable only by engaging n the

ti

d

f i

t it t d d

f

ll

S t d d i t l t th

f i

t h f

d t i

h t it

t b

d

titi

E h

f i

h

hit

d

ifi h t

tht

ti

tditi

ii

f i l

t

l t i t it i t

(Mlt

1984 17 175 187 1 9 0 2 0 3 )

H d

B d

d F k Mill

ff

f

f i t l i

t

l i th

f d t i

f

d i l thi

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

Physicians by virtue of becoming socialized into the medical profession accept alle

i

t

t f

l l

h i h dfi th

t

f dil

ti Th

l

i ri t t l t

f th

l dti i b t

hii

i thi

f i l

l

d i d i t th i t

t hii

Th professional integrity of physicians is constituted by allegiance to this internal morality (Brody and

Mill 1998 386)

These writers and others like them maintain that moral frameworks in the profes

sions derive from rolespecific duties and professional virtues

N

bl d i t t h t

f i l

l i

t

l bliti

didl H

i t l

lit

t i l

tb

d t l

h i

h t

ll

t b l Trditi

d

f i l

t d d

t

f

l d

d

f t t l

f i l

d i

dii

b i

j l i

i i

d th fild ft

ilif

l

i t

k th

idfibl

iid

li

lt

d th

ity than they are entitled to claim

Brody and Miller address this problem by distinguishing between the core moral

norms appropriate to a profession and the dogmatic and unsystematic provisions

f d i

d

f

f i l

thi A th

it

i t l

lit

d hld

l i th f

f

il h

"Even the core f

dil

lit

t b thhtfll

l t d

d

t t d

t i t l

d th

t t i

ill b

id

t b th

h li i

d

it

h

i i t b l

i f l d b

itl

l

th i t t th h i t " ( B d

d Mill

1998

3 9 3 4 397

h i

ddd)

T h h

t thi i

i ftl t i t l i

It h

tht i t l

t d d

may be shallow and expendable whereas some external standards are deep and

essential Even current practice standards might be weak and insupportable We

also know from recent history that a meaningful reconstruction of traditional pro

f i l

di t i t t i l

liti t

dt

l t l h

i

likl t

b

l t th i t l

t d d

f

f i l

lit

C i d

thi h i t i l

l I th l t 1960 th b k A Time to Speak: On

Human Values and Social Research b

il

h l i t H b t Kl

b

lihd j t

b

f

t i l

f d

f b

fh

bjt

b

i l i t i t (Kl

1968) K l '

b k

d th

f t i d

k

ll l t i

i l i t i t t th f t t h t th h d

i

d f i i i

in standards of research ethics Careful attention was subsequently paid to the

moral judgments that psychologists should make in carrying out their research and

to the many defects of standards in the then prevailing practices Problems were

f d i

ti

h

th

i t l d t i

f b j t th

llti

f

dt

i

i d i i d l l idtifibl f

d th

f

fiil

i

ti

t

bti

bjt

It b

l

t h t th

ili

ti

t d d

d t

t dd

th

ti

Externalism

A th

t i l

t l

b

t t

lit? A

t l

t i t l

lit i

t d d

tht i

f i l

t

d itit

d l

THE NATURE OF APPLIED ETHICS

tht

ti

l t

t th

f

i t l

lit P b l i

ii

law religious institutions and philosophical ethics have all served (whether justifi

ably or not) as sources of external morality

One influential answer in philosophy to the question of which external source is

t

i t i t h t t h i l th

id th

it b i f

lid

thi A

l i f d i th

k fB d G t

dD

Cl

Th

i t i tht t

k

dj d t

i

l i d thi th

t b "

i l

i f d t h i l t h " Th

l f t h i th

i t

id "

f

k

h i h ll f th d i t i

ti

"

d t

i

"id

i t

tht

tititil

ll l " Th b l i

t h t t h i th

will alert attentive persons to issues of applied ethics identify the morally relevant

features of circumstances determine the difference between morally acceptable and

unacceptable solutions to problems and show which conditions are necessary and

f f i t t j t i f th

ilti

f

l

l (Cl

d G t 1990

2 3 1 2 f G t t l 1997

3 6 1519)

Gt

d Cl

d

t h l d t h t th

i

l

li

it

t l

t d d f

f i l

thi O l t h i th

d

ll th

t h i

ftll f l d

di b l

f

d di

P

t

f th t h i

ll

assume a similar partisan stance Independent of this confusion over whether one

particular theory is morally authoritative it is often unclear whether and if so

how a philosophical theory is to be used to criticize internal standards or address a

diffilt

l

bl

If

ld b

fidt tht

t h i l th

lid h

b t b i

ld

k

t t i l

til

d li

ti

b

i l

ki th

i t h t th

ifi H

t

t

h

h th

d

l

it tht

th

f thi

d i

ti

i likl t

B t h ithi

d i t h t h i l h th t h i

tht i

f

t t d th th

i t t

f th

il

lit

f

h i h th

i

E

if

idiidl i

i d tht

til

theory is correct (authoritative) he or she needs to deal responsibly with the fact

that other morally serious and informed individuals reject this conviction

Skepticism about the practical relevance of theory is not surprising in light of the

f t tht h i l h

h

tditill tid t

li

d jtif

lit t

lif

l

t t

i h

lj d t

d

t

d

d t

b i

i i l

f

l

t t

ti t h i

t

l

til

l

bl

d l i t

d

f

f i l

thi

G l

t h i

ill i t d

ll

itd f

til

kb

th

dd

h i l h i l

bl

tht

i t h l

d i d f

ti

Althh b t

l

ity philosophical theories are primarily attempts to understand or unify morality

not attempts to specify its practical commitments

Mixed interncdism and externalism

A thid t

f

bth i t l i

d

t

i l t d

f th

f i

d

h t th

t t f

lid thi i

t l i

It t t

ith th

iti

i difft

i di

lt

th t t d i t i t t i

b d b

t

tht

d

t

l

f

it

M b

l t d d

ht

5

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

fid t

l b thi

b h i ( i t l

l i t ) b t l b th

moral standards of the broader culture or community (an external morality) The

authority to practice is itself granted by society on the condition that its professions

and institutions will in a responsible manner be educated in and adhere to the high

l t d d

td b tht

i t If

f i

d ititti

td t

f

thi

ti

t h t th

ili

l l

f th l

it

ill b h d

i

ti Th

il t d d

di t th

t

ti

ill

f

it t

it I t l

liti i th

f i

ill

dil b

th

i i i f i t

d d t

th

t l

liti

A theory of this description has been advanced by H Tristram Engelhardt He

holds that profound disagreement exists about the nature and requirements of

professional practice across larger communities such as Orthodox Judaism Roman

Cthlii

Hidi

d

l

h i

There is no way to discover either a canonical contentfull secular morality or the

t

ll

ttfll

lti

t t

h th

t b d b th

lit f h d

l ii t h t bid

lf i d M l t

d

t

see the world in the same way Moral strangers [cannot] resolve contentfull moral

t i

b

d t i l

t M l fid

th th h d

di

idl

h d h

h

i i

(Elhdt

d Wild 1994 136

l 13547)

A d i

t E l h d t

ttfll

lit

difft

iti

Th

t l k f Othd

Jdi

f

l d t i

ht i

t

bl

tbl

l f tht

ti

f th J i h

ti

hih

t it

dititi

F

thi

ti

l t d d

f ht i blit

d

permissible for professionals in medicine politics law and business derive from the

more general moral commitments of a larger community beyond the narrower

community of professionals

Th d

lthi t

k i thi

t i k t i l th

btti

f d t i

f

l

l i d thi

d lki

h f d t i

th

f d t i

f

t f

l i d thi

th th h i t i l

t i

iti N i t l

lit

it

t i th

t l

lit f

til

lt

(Elhdt

d Wild 1994 1 3 7 8 E l h d t 1 9 9 6 1 0 5 2 4 )

Thi

t h

i i h t i t th

lti

bt

t l

d i t l

liti

b t it h

k

B

h i i

d i i t

it i

t

overlook basic similarities; that is to neglect the core of near identical moral goals

interests and commitments that exist among welltrained professionals from differ

t

l t l b k d

F

l

h i i

ll

th

ld h

l

d t h i

fhli

lliti

hbilitti

i d i f t

di

ti t t i

d th lik Th

i

h d

l i i t (h

iitd)

d

h d

f

f i l

ti

th

iti

P d i l l

thi th

l

tt

th d

f h d

t ithi

"th

iti

f

l f i d " tht f

th

i

f th

t

Th th

ii

h i

i l

h d

ifit i

h

it

THE NATURE OF APPLIED ETHICS

ff i d

hih

bl

tbl

d libl

t

di th

l f th

professions and professional ethics However in communities of almost any size

there exists a pluralism of viewpoint These communities are not lacking in sub

groups with different moral points of view and hopes to revise prevailing conditions

ti

d d C h i

i t

f b i t i

d t i

i d t i

liti

th

lti

f iil i h t

d th lik

k f flid

i t

th

iti

ith

t

dt

l

iti

Ath

k

i t h t thi

i d i t l i t t l i t

t fftil

ld

l t l tht i

it j d t

Th

lidit f

l

dj d t

d d

i thi

t

thi

d

t

b

nity; no transcendent principle warrants crosscultural appraisal It follows that

there are no universal human rights that protect individuals Human rights are by

definition valid claims that are justified by reference to morally relevant features of

h

bi

tb

f

t

l t d d

It i l d i f f l t t

h

i thi th

ll

td

bli

li i t

b f h i d i

lliti

i t It i

t

h

thi th

tf

i t

lii i

i t ititti

b t it i b i l i t t

li

tif

d iti

i

bli

li

k it

t ft h

ith th

d

ld d

bl t

apply ethics to our deepest social problems

Problems of Method and Justification

S l

dl

f

thd

ti

lld

thd

dl

f

tifti

h

b

d i d i

l i d thi

Th

f th

t i f l t i l

dl

t t d i thi

ti

Th

fit

dl

h jtifiti

d

thd f

t d

ti t h t

h i

l

d t h i l th

Th

d

approaches justification and method from a bottomup perspective that emphasizes

moral tradition experience and particular circumstances The third refuses to

assign priority to either a topdown or a bottomup strategy

Top-down models

I

th

fit

dl

iti

Thi

dl

f

t th

ll it

thd i l

li

t h t fll

d th

l Th

"applying" a rule:

ti

lid t

hih i t l l

ll

l l ( i i l

idl

flli

i th d d t i

f

i

ti

l

iht

i

it

t thik

t) t

l d i

1 Every act of description A is obligatory

2 At bi fd i t i

A T h f

3 At bi blit

Thi

d

dl

libl

b i l

d

d i

i

hih t h i

th

l

d

i l

f

j d t

b h t

ditl

i i l

b t it l

t l

libl

l i i l

j

i i t i thi

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

t d i t i l

ti

i t i t t i l

l

d

j d t

Whil

h i th

moral life conforms roughly to this conception of moral priority much does not

There are several problems with this moralpriority thesis First moral judgments

in hard cases almost always require that we make the norms themselves more

ifi (

th

ti

"Pbl

f S i f t i " b l ) bf

bi

til

i t

d

i

l

i i l

I th

f

ifi

di

ki

til

j d t

ft

t tk it

t f t l

blif

b t th

ld

l t l

tti

j d t

f likl

t

d

i

d t t h l fill t d i

iht t

l

i i l

d t h i

Th

i

l

l i i t i th

S d

th f t

f

itti

also be such that no general norm (principle or rule) clearly applies and the differ

ent moral norms that can be brought to bear on a set of facts may yield inconclu

sive results For example destroying a nonviable human embryo or fetus does not

l l

ilt

l

i t killi

d

d

th

l tht

h

iht t

t t bdil i t i t

d

t l l

l t thi

li

E

if

h

ft

t i h t th h i

fft

d th h i

f l tht

d

l t

ill

t

j d t tht i i t i b l

ith

th

' hi

fft

d l Slti

th i h t t f f t

db i i

th

right set of rules to bear on these facts are not reducible either to a deductive form

of judgment or to the resources of a general ethical theory

The topdown model also creates a potentially infinite regress of ustification a

di

d d

f fil j t i f i t i

b

h l l

f

l t

i

t

i

hih

l l t j t i f it If t d d

jtifid

til b h t

d

jtifid

i

t it

ld

th

ti

f thi

h t h t th

jtifid

i i l

j d t

I th

ld h d l thi

bl

b

ti

tht i

lfjtifi

t h t it i i t i l

t t hld b t

f tht

thi t t

d

t h t th j t i f

ll th

i i l

d l i

t d d

tht

t thil

theory is well equipped to meet

Bottom-up models

S

it

i

l i d thi

t thi

ttti

l

h

til

d i i

d

th th

l i i l

d t h i

Th

bli

tht

l

i

d jtifiti

d btt

t t d

Th

it t

f iti

il

t

d

ti

i i h t d i

l

d

ti

l i

th t t i i t

f

hih

commonly make moral decisions They also depict an evolving structure of moral

beliefs based on exemplary lives and narratives experience with hard cases and

analogy from prior practice

Btt

dl

ttill i l d

lditit

t h d l i

C i t

h

b

th

t idl d i d i

l i d thi b t

i

f

f

ti

t i l i

d th

thd

l

lif P

t

f th

h

l i i l

d i t i

i th

d

fk l d

t i

T h t i th

i

f t i

d iht f

i i l di

f

i

l t l

i

til

i t

(J

dT l i

1988) F

l

h i i

8

THE NATURE OF APPLIED ETHICS

dd i t h d i

i

l i f i

t h l i

f

tit

t fi

missible killing But progressively after dealing with many agonizing cases they and

society came to frame many of these acts as forms of permissible allowing to die or

even as morally required acts of acknowledging refusals of treatment All practical

l l

b t killi

d ltti

di

i

d

f d

ti

th

b

th

i i l l

it i

l t l

ti

f idli

A

it'

l i

fid thi

tt h h

bddd

l tditi

d

t f

d

tht

it d

ft

iiht

d j d t

A

l

t th

thit

ti i

l i

ti

id t b t th h t

f thi

thd

h th d i i

f

jit

fj d

b

thitti

i

case the judgments in their decision are positioned to become authoritative for other

courts hearing cases with similar facts Defenders of bottomup reasoning see moral

authority as analogous: social ethics develops from a social consensus formed

d

hih

th b

t d d t

itht l

f th

ltd

l id

A

hit

f iil

d iil

d t

t

it b

i i l

f d t i it

l

l i

d

k l d

liti

( l

i i l ) i it

li

tditi

f

thil

flti

Case analysis which is central to casuistry has long been used in law schools

and business schools Training in the case method is widely believed to sharpen

skills of legal and business reasoning as well as moral reasoning One can tear a

t

d th

t t

btt

ft t i

iil

itti

I th

t h t d

l

tti

t h

d t d t

lik

h

l i

b t iht

d b t

t

i

Th b j t i

i t

d l

it t

bl

d t fd

l lti

tht

k i th

t t

k i

h

t

d ti

i d th

k i

tht

thi i th

th b i

f f d t i l

l

fl i

t

Th

thd i l

h

t b

d t d

ble facts and judge the weight of evidence enabling the transfer of that weight to new

cases This task is accomplished by generalizing and mastering the principles that

control the transfer usually principles at work in the reasoning of judges Use of the

thd i b i

h l

i

f

idl f d t i

tht

t th

t d t i th d i i k i

l ft

iitil i i

i t th f t

f

l

itti

H

th

f th

thd i t

t

itti

lt

ith th f t

ii

d

jdi

tht

iht

t

dt fd

f ki

it d i i

i

h

i

t

A

ith t d

t h i

i

bl

li i

it f

d f d

f btt

up theories First defenders sometimes write as if paradigm cases or particular

circumstances speak for themselves or inform moral judgment by their facts alone

Clearly they do not To move constructively from case to case or to attend to the

l t f t

f

til

itti

id

l f

l l

t

t th

itti

Th

l i

t

t f th

itti

bt

th

f i t t i

d liki

itti

All

l i l

i

i

ti

t i d i t tht

bjt

t i ik

lik

th i

l t

t Th

ti

di

f th

i

t l i k i

t b

h i d b

l

itlf Btt

t

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

t h f

t

i i l

l

i

til

l l

ents in the case or set of facts at hand

"Paradigm cases" and "morally relevant features of circumstances" seem to com

bine facts that can be generalized to other situations (for example "The employee

bl

th

hitl

th

l " )

d ttld

l

(f

l

" K l d b l

l

h

iht t d i l

th

di

f th

l " ) Th

ttld

l

ltill ditit f

th f t

f

til

Th

l th

t l

l

ti

th l

th

t th t t

f

l i i l

l

Btt

t l

t

bl

h

th

it

fliti

l

gies judgments and case interpretations Defenders stress that cases and particular

circumstances point beyond themselves and evolve into generalizations but they

also may evolve in the wrong way if they were improperly grounded from the

t t Btt

t h

l

t h d l i l

t

t

b i d d l t

f

l t f l t ft

f

Th

bl

l d t

ti

b t th j t i f i t

f th

t

H

d

jtifti

? I it

l b

il

ti

d

l ? Miht

t difft

l i

d

l

t

ti

"iht"

? With

out some stable framework of norms there seems to be a lack of control over

judgment and no way to prevent prejudiced or poorly formulated social conven

tions This criticism is a variant of the muchdiscussed problem that bottomup

t l k

i t i l dit

f

l t l blid

h

l

d

l

ii

Idtifti

f th

ll

l t f t

f

d d

th

h

k j d t

b t

d th

idiidl

ld

t f

tilit

d i i

bi

jdiil

f

l

tht i

h k d b

tbl

t

fi t i l

i i l

dh

iht

Th h t

f th

bl

b t h t th

t

t

thd

itht

t t tht i

t l ft h h t tht dil

th f d t l i t

f

comparison and analogy in moral thinking but that lacks initial moral premises It

is certain that we reason morally by analogy almost daily and we are often confi

dent in our conclusions However such analogies also often fail and analogies

t

li

ftth

tit

Thi

t h d th

l

ith th

bl

tht

tt h

ti t

i t

iitill h

if

f

th f t i t

t

t

th

t i th

d i

t

i l d

d

fl

t t t

Coherentism

"The top" (principles theories) and "the bottom" (cases particular udgments) are

both now widely regarded as insufficient resources for applied ethics Neither gen

l i i l

til

i t

h

ffiit

t

t

l i

ith th

dd

libilit P i i l

d t b

d

if f

d

l i

d i l l i t i

f

l i i l

I t d

f

t d

btt

dl

t

i

f

th

dl

i l

f d t

"flti

ilibi"

d" h

t h "

10

THE NATURE OF APPLIED ETHICS

Jh R l '

l b t d

t f "flti

ilibi" h b

th

t

influential model of this sort In developing and maintaining a system of ethics he

argues it is appropriate to start with the broadest possible set of considered moral

judgments about a subject and to erect a provisional set of principles that reflects

th

Rflti

ilibi

i

i t i t i

i thi ( d th

t t i )

flti

tti

f

l i i l

t h t i l

tlt

d th

l t

l blif t

k th

h t

ibl

" C i d d j d t " i

t h i l t

f i

t j d t

i

hih

l blif

d

iti

t likl t b

td

itht

ditti

bi

E l

j d t

b t th

f

il d i i i t i

li

gious intolerance terrorism torture and political conflicts of interest These con

sidered judgments occur at all levels of generality "from those about particular

situations and institutions through broad standards and first principles to formal

d b t t

diti

l

t i "

E

th

i d d j d t

tht

t" i i l l

fid

it"

R l

"libl t

i i " Th

l f flti

ilibi

i t

th

d djt

i d d j d t

i

d t

d th

h t

ith th

i

f

t

l

l

i t t

W t t

ith

d

d t

of moral lightness and wrongness and then construct a more general and more

specific account that is consistent with these paradigm judgments rendering them

as coherent as possible We then test the resultant actionguides to see if they yield

i h t

lt If

d j t th

id

i th

d

th

W

ltl

tbl

ilibi

th

i

d

djti

b

td t

t i l l ( R l 1971 20ff 4 6 5 0 5 7 9 8 0

[1999

d 17ff 4 0 5 5 0 8 9 ] 1996 8 381 384 399)

T tk

l i th thi

f

t l t t i

i i

tht

t t t d t

h ft

lii

(1) d i t i b t

b

td

b

f

f

i l (i

d t

i i

th b f i i l

t

f th

d )

d (2)

distribute organs by time on the waiting list (in order to give every candidate an

equal opportunity) As they stand these two distributive principles are not coherent

because using either will undercut or even eliminate the other We can retain both

(1)

d (2) i

th

f fi ditibti

bt t d

ill h

t i t d

liit

bth i i l

t t h

ith

t fh

t

if

i t t

d bl

th

i t t

i t th

i t t

Th

liit

d

t ill i t

h

t b

d

h t

ith th

i i l

d l

h

di d i i i t i

i t th l d l

d th

l f bilit t

i

j t

h

f th l l t i

f

i

dil

d

We have no reason in applied ethics to anticipate that the process of achieving

moral coherence will either come to an end or be perfected A moral framework

adequate for applied ethics is more a process than a finished product; and moral

bl

h

d l i

th

t itbl

t

f

t

d

ditibti

hld b

i d d

j t i

d f

t i l

d j t t b

flti

ilibi

W hld

i

l i d thi t h t

f

di

h f i h

df

l itti

tht hll

t

lf

k

( R l 1971 1 9 5 2 0 1 [1999

d 1716])

11

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

One problem with this general model is that a bare coherence of norms never

provides a sufficient basis for justification because the body of substantive udgments and principles that cohere could themselves be morally unsatisfactory This

points to the great importance but also the great difficulty of starting with considered judgments that are themselves morally justified These considered judgments

presumably will have a history rich in moral experience that undergirds our confidence that they are credible and trustworthy; but how is one to justify such a claim

in the case of any proposed set of considered judgments? After all the persons

codes institutions or cultures from which the premises descend may not themselves be highly reliable For example the Hippocratic tradition the starting-point

in medical ethics for centuries has turned out to be a limited and generally unreliable basis for medical ethics

In addition vagueness surrounds the precise nature and scope of the method of

appeals to coherence A philosopher seeking coherence might be pursuing one or

more of several different interests: evaluating public policy constructing a moral

philosophy improving his or her personal set of moral beliefs and so on The focus

might be on judgments on policies on cases or on finding moral truth It is also

not clear how we should and should not achieve coherence or how to be sure that

we have done so

In light of the differences in the models explored in this section and the diverse

literature in applied philosophy it is questionable whether applied ethics has a distinct method or type of justification Applied philosophers appear to do what philosophers have always done: they analyze concepts examine the hidden presuppositions

of moral opinions and theories offer criticism and constructive accounts of the moral

phenomena in question and criticize strategies that are used to justify beliefs policies

and actions They seek a reasoned defense of a moral viewpoint and they use considered judgments and moral frameworks to distinguish justified moral claims from

unjustified ones They try to stimulate the moral imagination promote analytical

skills and weed out prejudice undue emotion false authority and the like

From this perspective differences between traditional ethical theory and applied

ethics can be easily exaggerated In philosophy journals that publish both applied

and theoretical work no sharp line of demarcation is apparent between the concepts and norms of ethical theory and applied ethics There is not even a discernible

continuum from theoretical to applied The applied-theoretical distinction therefore

needs to be used with caution (Beauchamp 1984: 514-31; Gert 1984: 532-48)

Problems of Specification

It is now generally agreed in literature on the problems addressed in the previous

two sections that specific policy guidelines and truly practical udgments cannot be

squeezed from abstract principles and general ethical theories alone Additional

content must be introduced from some quarter General theories and principles f

used at all must be made specific for contexts; otherwise moral guidelines will be

empty and ineffectual The implementation of these general norms must take account of feasibility efficiency cultural pluralism political procedures uncertainty

12

THE NATURE OF APPLIED ETHICS

b t

rik

li

b difftd

ti

l dil

d th lik I

short theories and principles must be specified for a context

Specification should not be understood as a process of producing general norms;

it assumes they are already available It is the process of making these norms

t

t h t th

ifll

id

d t Sifiti

i

d

i

th i d t i t

f th

l

t

i th

i

d

ti

idi

it

hil

tii

th

l

i t t

i th

i i l

Filli

t th

i t t

f th

ith h i h

t t i

lihd b

i

th

f th

t

l b

lii

h t th

l

Th

i

d

H

Rihd

t it b " l l i

t

where when why how by what means to whom or by whom the action is to be

done or avoided" (Richardson 2000: 289; see also Richardson 1990: 2 7 9 3 1 0 )

For example without further specification the principle "respect the autonomy of

t t

" i t

t hdl

litd

bl

f ht t

k f i liil

dii

d

h i l i

h

bjt A

dfi

iti

f" t

f

t "

(

" l l i

t t

t

i

thi libt

riht")

iht lif

'

i

bt

ld t

th

l

d it

if S i f t i

i

d i f f t kid f

lli

t th

analysis of meaning It adds content For example one possible specification of

"respect the autonomy of competent persons" is "respect the autonomy of compe

tent persons after they become incompetent by following their advance directives"

Wh

i th

f thi

til

ifti

b t l

t

diffilti i l i

d

diti

ld

if f t h

fll

" R t th

t

f

t t

( f t th b

i t t )

b

flli

thi d

diti

if d l if th d i t i

l

d

tii

t th i t

t h d " A th

bl

th

f

ifi

ti

ill

ti

Tht i l d

ifd

l

idli

d lii

ill b

fth

ifd t h d l

l

i t

Thi

i

specification is one way to practice applied ethics and it may be the best way

In progressive specification there must remain a transparent connection to he

initial norm that gives moral authority to the string of norms that develop over

ti

Th

i l

th

ibilit f

th

ifiti

bi

bl

d it i

ibl t h t d i f f t

ti

ill ff d i f f t

ifti

Th

ti

ifti

ll b t t t i

d jtifibl

Of

t ll

j t i f i b l Th

t f

f i l

iti

(i

ifti

thi

d

lii

d

j d t ) h

ft b

t

d

i

th h

b

b i d

d l f t t i

P f i l

thrit

i thi

way protect shoddy moral reflection In the process of specification overconfidence

in one's specifications is a moral vice that can have profound consequences

Moral disagreement in the course of formulating specifications is inevitable n

t t

I

i

b l t i

d i l t i

l

ti

ifti

itll

ti t b ffd bt l t t i

ifiti

d

t b

tt

f

t

th

th

i

th

t t i

hih

flti

ff

l t t i

lti

t

til

bl

Thi

b t i

tk

t th

bjt fh

hld i

itti

i

hih

llitdd

d i i

dk l d b l

fid

t h l

i

d

i

t

13

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

Problems of Conflict and Disagreement

Moral disagreements emerge in the moral life from several different sources These

include disagreements over which specification is appropriate factual disagreements

(for example about the level of suffering that an action will cause) conceptual

disagreements scope disagreements about who should be protected by a moral

norm (for example whether fetuses or animals are protected) disagreements

resulting from a genuine moral dilemma disagreements about which norms are

relevant in the circumstances and disagreements about the weight of the relevant

norms in the circumstances

It should not be presumed in a context of disagreement that at least one party is

morally biased mistaken or otherwise deficient Conscientious and reasonable

moral agents who work with due diligence at specification and reasoning about

moral problems sometimes understandably disagree The parties may disagree

about whether religious values have any place in political affairs whether any form

of affirmative action is viable whether physician-assisted suicide is ever acceptable

and dozens of other issues in applied ethics

When evidence is incomplete or different sets of evidence are available to different

parties one party may be justified in reaching a conclusion that another party s

justified in rejecting We cannot hold persons to a higher standard than to make

judgments conscientiously and coherently in light of the relevant basic and specified

norms together with the available evidence Of course tolerance for some norms

rightly has its limits The method of specification offered in the previous section

needs enrichment by an account of moral justification that will help distinguish

justified and unjustified specifications The models of method and ustification discussed in earlier sections may be our best resources in this endeavor but if so

these resources stand in need of further development to be of real practical assistance in applied ethics

Conclusion

A robust confidence in and enthusiasm for the promise and harvest of applied ethics

is far from universal Many are unconvinced that traditional philosophical ethics or

contemporary ethical theory can play any significant role in case analysis or in

policy or professional contexts There is for reasons discussed throughout this chapter skepticism that philosophical theories even have practical implications (or applications) However these suspicions may rest on misconceptions of the nature of

applied ethics No morally serious individual doubts the importance of the issues

treated in applied ethics and virtually everyone familiar with work in the field can

cite some examples of outstanding applied work The better view is that adequate

conceptions of the method and moral content of applied ethics remain a project n

the making

14

THE NATURE OF APPLIED ETHICS

References

Beauchamp T L (1984) On eliminating the distinction between applied ethics and ethical

theory The Monist, 67: 514-31

Brody H and Miller F G (1998) The internal morality of medicine: explication and application to managed care Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 23: 384-410

Clouser K D and Gert B (1990) A critique of principlism The Journal of Medicine and

Philosophy, 15: 219-36

Engelhardt H T (1996) The Foundations of Bioethics, 2nd edn New York: Oxford University

Press

and Wildes K (1994) The four principles of health care ethics and post-modernity In

R Gillon (ed) Principles of Health Care Ethics, pp 13547 London: John Wiley

Gert B (1982) Licensing professions Business and Professional Ethics Journal, 1: 51-60

(1984) Moral theory and applied ethics The Monist, 67: 532^48

Culver C M and Clouser K D (1997) Bioethics: A Return to Fundamentals. New York:

Oxford University Press

Jonsen A and Toulmin S (1988) The Abuse of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning.

Berkeley CA: University of California Press

Katz J with Capron A and Glass E S (1972) Experimentation with Human Beings. New

York: Russell Sage Foundation

Kelman H (1968) A Time to Speak: On Human Values and Social Research. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass

Maclntyre A (1984) After Virtue, 2nd edn Notre Dame IN: University of Notre Dame Press

Rawls J (1971) A Theory of Justice. Cambridge MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University

Press (rev edn 1999)

(1996) Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press

Richardson H S (1990) Specifying norms as a way to resolve concrete ethical problems

Philosophy and Public Affairs, 19: 279-310

(2000) Specifying balancing and interpreting bioethical principles Journal of Medicine

and Philosophy, 25: 285-307

Further reading

Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments (1996) Final Report. New York:

Oxford University Press

Altaian A (1983) Pragmatism and applied ethics American Philosophical Quarterly, 20:

227-35

Beauchamp T L and Childress J F (2001) Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 5th edn New

York: Oxford University Press

Brock D W (1987) Truth or consequences: the role of philosophers in policy-making Ethics,

97: 786-91

Daniels N (1996) Wide reflective equilibrium in practice In L W Sumner and J Boyle (eds)

Philosophical Perspectives on Bioethics, pp 96-114 Toronto: University of Toronto Press

DeGrazia D (1992) Moving forward in bioethical theory: theories cases and specified principlism Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 17: 511-39

15

TOM L BEAUCHAMP

Dworkin R (1993) Life's Dominion: An Argument about Abortion Euthanasia and Individual

Fd

Feinberg J (1984-7) Th Ml

Liit

f th C i i l L

4 vols New York: Oxford University Press

Freeman E and Werhane P (eds) (1997) Dictionary of Business Ethics Cambridge MA:

Mthil

hy 20: 222-34

Maclntyre A (1984) Does applied ethics rest on a mistake? The Monist 67: 498-513

Alid

Ethi i

Tbld

Wld

Dordrecht: Kluwer

Rachels J (1990) Created from Animals: The Moral Implications of Darwinism New York:

Oxford University Press

Mtt

f Lif

d Dth N I t d t

E

i Ml

Philh

3rd edn New York: McGraw-Hill

Reich W (ed) (1995) Encyclopedia ofBioethics 2nd edn New York: Macmillan

AC

Alid

i

Ethi

t Ethi

(1993) P t i l Ethis 2nd edn New York: Cambridge University Press

Sugarman J and Sulmasy D P (eds) (2001) Methods in Medical Ethics Washington DC:

Sunstein C (1993) On analogical reasoning H d

Winkler E R and Coombs J R (eds) (1993) Alid

well

16

L Riw

106: 741-91

Ethi A Rdr

Cambridge MA: Black-

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Azoth, August 1919Document68 pagesAzoth, August 1919Monique Neal100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Vizconde v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 118449, (February 11, 1998), 349 PHIL 883-897)Document10 pagesVizconde v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 118449, (February 11, 1998), 349 PHIL 883-897)yasuren2No ratings yet

- Petition For Declaration of Nullity of Marriage (PI)Document8 pagesPetition For Declaration of Nullity of Marriage (PI)dave_88opNo ratings yet

- Sample Judicial AffidavitDocument4 pagesSample Judicial AffidavitHaryet SupeNo ratings yet

- Guardian's Bond PetitionDocument4 pagesGuardian's Bond PetitionKvyn Honoridez86% (7)

- God Is Calling His People To ForgivenessDocument102 pagesGod Is Calling His People To ForgivenessCharles and Frances Hunter100% (1)

- Troop Guide To AdvancementDocument73 pagesTroop Guide To AdvancementdiharterNo ratings yet

- Al-Jaber International Company: Procedure Change ManagementDocument4 pagesAl-Jaber International Company: Procedure Change ManagementImtiyaz AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Motivation LetterDocument1 pageMotivation LetterRin AoiNo ratings yet

- SC Rules on President's Power to Suspend Local OfficialsDocument3 pagesSC Rules on President's Power to Suspend Local OfficialsJudiel Pareja50% (2)

- AFFIDAVIT FORMS - Docx - 1561726127016Document6 pagesAFFIDAVIT FORMS - Docx - 1561726127016johngabrielramos15No ratings yet

- Self AssessmentDocument10 pagesSelf Assessmentapi-401949389No ratings yet

- 30.weber (2008) Codes of Conduct, Ethical and ProfessionalDocument6 pages30.weber (2008) Codes of Conduct, Ethical and ProfessionalRicardoNo ratings yet

- Ejbo Vol12 No1 Pages 5-15Document11 pagesEjbo Vol12 No1 Pages 5-15Noy AmaralNo ratings yet

- 29 Donald 1Document4 pages29 Donald 1GonzaloNo ratings yet

- 23.UNIT 5 BP Deepwater Horizon ArraignmentsDocument2 pages23.UNIT 5 BP Deepwater Horizon ArraignmentsRicardoNo ratings yet

- 24.DEBATE 5 Scientists Guilty of Manslaughter LAquilaDocument2 pages24.DEBATE 5 Scientists Guilty of Manslaughter LAquilaRicardoNo ratings yet

- 26.codes of EthicsDocument6 pages26.codes of EthicsRicardoNo ratings yet

- 22.the Precautionary PrincipleDocument7 pages22.the Precautionary PrincipleRicardoNo ratings yet

- 21.RISK PerceptionDocument11 pages21.RISK PerceptionRicardoNo ratings yet

- 16.DEBATE 3 Do Engineers Have Social ResponsibilitiesDocument2 pages16.DEBATE 3 Do Engineers Have Social ResponsibilitiesRicardoNo ratings yet

- 20.DEBATE 4 Who Is Responsible of Environmental DamageDocument1 page20.DEBATE 4 Who Is Responsible of Environmental DamageRicardoNo ratings yet

- 19.UNIT 4 Engineering EthicsDocument1 page19.UNIT 4 Engineering EthicsRicardoNo ratings yet

- 13.ethics and Social Resposibility of Scientist and EngineersDocument7 pages13.ethics and Social Resposibility of Scientist and EngineersRicardoNo ratings yet

- 17.beneficence and PaternalismDocument12 pages17.beneficence and PaternalismRicardoNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Professionalism - September 2004Document13 pagesConcepts of Professionalism - September 2004Vikram UnnikrishnanNo ratings yet

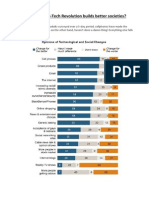

- 12.DEBATE 2 SciTech Revolution Builds Better SocietiesDocument1 page12.DEBATE 2 SciTech Revolution Builds Better SocietiesRicardoNo ratings yet

- 11.UNIT 2 Science As A Human RightDocument1 page11.UNIT 2 Science As A Human RightRicardoNo ratings yet

- 03 - Attachment-8-Manufacturer Authorization FormDocument1 page03 - Attachment-8-Manufacturer Authorization FormPOWERGRID FARIDABAD PROJECTNo ratings yet

- Social Interaction & Social Process in SociologyDocument50 pagesSocial Interaction & Social Process in SociologyKesiyamol MathewNo ratings yet

- Blass-Spilitting - 2015-The International Journal of PsychoanalysisDocument17 pagesBlass-Spilitting - 2015-The International Journal of PsychoanalysisAvram OlimpiaNo ratings yet

- Let's Try This Career BeliefsDocument4 pagesLet's Try This Career BeliefsPhuamae SolanoNo ratings yet

- TLE 10 Module: Member: Daughters of Charity-St. Louise de Marillac Educational SystemDocument16 pagesTLE 10 Module: Member: Daughters of Charity-St. Louise de Marillac Educational SystemPeter Vukovic100% (1)

- Indian Management Thoughts & PracticesDocument15 pagesIndian Management Thoughts & Practicesdharam_devNo ratings yet

- Work Smart, Not Hard PDFDocument4 pagesWork Smart, Not Hard PDFavabhyankar9393No ratings yet

- Letter Calling For Jennifer Granholm's ResignationDocument5 pagesLetter Calling For Jennifer Granholm's ResignationNick PopeNo ratings yet

- The 8-Fold PathDocument7 pagesThe 8-Fold PathDiego GalliNo ratings yet

- Cheater Power in Postmodern EraDocument27 pagesCheater Power in Postmodern EraAdryan Fabrizio Pineda Repizo100% (1)

- Class 10A Building Fact Sheet March 2010Document3 pagesClass 10A Building Fact Sheet March 2010Andrew MichalopoulosNo ratings yet

- UTS Module 2Document2 pagesUTS Module 2Swag SoulNo ratings yet

- Humanae VitaeDocument5 pagesHumanae VitaeVictor PanlilioNo ratings yet

- Personnel Management Part-IIDocument184 pagesPersonnel Management Part-IIajit704687No ratings yet

- Action Speaks Louder Than WordDocument3 pagesAction Speaks Louder Than Wordnabin bkNo ratings yet

- Summary Table of Theorists' Contributions and Personal ExamplesDocument4 pagesSummary Table of Theorists' Contributions and Personal Exampleskei arasulaNo ratings yet

- Ragudo vs. Fabella Estate Tenants Association, Inc. (2005)Document16 pagesRagudo vs. Fabella Estate Tenants Association, Inc. (2005)Meg ReyesNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of Law RE Shylock CaseDocument13 pagesMemorandum of Law RE Shylock CaseKei Takishima ShengNo ratings yet