Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Childhood Sexual Abuse - A Synthesis and Analysis of Theoretical Models

Uploaded by

solutions4familyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Childhood Sexual Abuse - A Synthesis and Analysis of Theoretical Models

Uploaded by

solutions4familyCopyright:

Available Formats

Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal

Volume 16, Number 2, April 1999

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

in Childhood Sexual Abuse:

A Synthesis and Analysis of

Theoretical Models

Patrick J. Morrissette, Ph.D., NCC, LCPC

ABSTRACT: The notion that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be

found in children who have experienced sexual abuse has become an important issue in research and clinical practice. To date however, there is a lack of

consensus on what theoretical model(s), if any, best account for PTSD within

this population. As a way of contributing to the existing body of literature

pertaining to PTSD and its relationship to childhood sexual abuse, this paper

synthesizes and presents a critical analysis of contemporary theoretical models.

As evidenced in the literature, there has been an explosion of information regarding child sexual abuse over the past decade. Within the

data pertaining specifically to the area of symptomatology, some attention has been rendered to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(Finkelhor, 1987). In an early paper, Gelinas (1983) for example, elaborates on chronic traumatic neurosis and notes that when female survivors of childhood sexual abuse seek treatment they typically show a

characteristic of disguised presentation which can be misleading and

result in unsuccessful therapy. Gelinas affirms a report by Rosenfeld,

Nadelson, Krieger, and Backman (1979) indicating that repercussions

of incest may be, ". . . subtle and varied and multi-determined, and

may manifest themselves immediately after the event or considerably

later in life" (p. 327). According to Gelinas (1983) the symptoms and

Patrick J. Morrissette, Ph.D., NCC, LCPC is Assistant Professor, Department of

Counseling and Human Services, Montana State University-Billings.

Address communications to Patrick J. Morrissette, Ph.D., NCC, LCPC, 1500 North

30th Street, Billings, Montana, 59101-0298; e-mail: Morris@WTP.NET.

77

1999 Human Sciences Press, Inc.

78

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

problems experienced by victims of sexual abuse can be accounted for

by three underlying negative effects resulting from: (a) chronic neurosis, (b) continuing relational imbalances and, (c) increased intergenerational risk of incest.

In an effort to advance and expand an understanding of PTSD

among sexual abuse victims, Herman (1995, 1992) suggests that the

current PTSD diagnosis is inaccurate and proposes the alternative

diagnosis of Complex Post-Traumatic Disorder. She argues that the

existing criteria for PTSD are primarily derived from survivors of

circumscribed traumatic events and therefore, fails to capture the

complexity of prolonged, repeated trauma that is often experienced

by victims of sexual abuse. In her view, an expanded concept of

PTSD would include a spectrum of disorders, ". . . ranging from the

brief, self-limited stress reaction to a single acute trauma, through

simple PTSD, to the complex disorder of extreme stress that follows

prolonged exposure to repeated trauma" (Herman, 1995, p. 97).

Although there have been relatively few studies pertaining to

PTSD among sexually abused children, it appears that this specific

disorder is nevertheless significant and worthy of further investigation. For example, in their extensive review of empirical studies regarding the impact of sexual abuse, Kendall-Tackett, Meyer-Williams, and Finkelhor (1993) found that PTSD has shown to be of

consistently high frequency among sexually abused children; particularly those who were pre-school and school aged.

A careful examination of the PTSD diagnosis, and its utility with

childhood sexual abuse, is important in order to appreciate the broad

range of other distress that such abuse might incur and to clarify the

appropriate diagnosis of PTSD. In addition, in order for professionals

to gain a better understanding of PTSD among sexually abused children, it is essential that they first become familiar with the various

existing theoretical models. The current challenge is to develop a theoretical formulation that is broader than PTSD and one which distinguishes sexual abuse trauma from other forms of trauma. This paper

synthesizes and provides a critical analysis of contemporary theories

regarding PTSD and provides foundational information in an effort to

advance understanding and perhaps trigger future research.

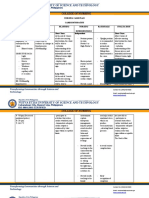

As a way of organizing information pertaining to each theory, the

various theories have been grouped into three broad categories including internal processing models, cognitive/behavioral models, and

formative models. To summarize the information a synopsis of the

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

79

research is also presented. A table designed to provide a quick reference of each model has been included (Appendix).

Learning Models

The Psychodynamic Model

Historically, the psychodynamic conceptualization of trauma was

based on the notion of energy overload in which the individual's stimulus barrier became overloaded (Lyons, 1987). The more recent formulations have focused on the individual's lack of schemata to assimilate the new information and the subsequent interference with daily

functioning to a significant extent.

A basic tenet of the psychodynamic perspective is that human behavior is viewed in a historical context. This means that there are

some childhood events such as sexual abuse that are linked to longterm harmful consequences and the onset of adult disorders (Beitchman et at., 1992; Friedrich, Beilke & Urquiza, 1987; Scott & Stradling, 1992). Within this framework, anxiety ensues when the ability

to cognitively process an event is thwarted. Psychodynamic models

(e.g., Horowitz, 1976; Marmar & Horowitz, 1988) assume that until a

traumatic life event is assimilated and satisfactorily integrated into

existing schemata, the psychological aspects of the event will continue to be activated in active memory storage. According to Horowitz

(1976) traumatic events provide information that must be integrated

by individuals into their view of self, of others, and of the world. For

example, a child who has been sexually abused may experience fear

at bedtime because of the recurring image and thoughts of the perpetrator.

Furthermore, the psychodynamic formulation proposes a phasic response in which individual differences are involved in the oscillation

that occurs between the intrusive experience state and the denial/

numbing state (Marmar & Horowitz, 1988). This framework of the

sequential phases of normal response (e.g., outcry, denial, intrusion

experiences, working through, and the completion of the response)

serves to organize pathological variants that may be seen as intensifications of these normal response tendencies (Marmar & Horowitz,

1988). Within this model it is possible to account for the presence of

common symptoms such as nightmares and flashbacks, the repres-

so

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

sion of memories, denial and emotional numbing. Symptoms begin to

subside when new information that has been stored in active memory

becomes part of the individual's perception of self.

This model may account for why sexually abused victims experience nightmares and flashbacks, but is not without its limitations.

Individual differences are not accounted for in any substantial detail.

In other words, some individuals may not experience sufficient symptoms to warrant the diagnosis of PTSD. Therefore, it is possible that

psychic overload is a symptom for some children and not for others.

This model also fails to account for the particular internal or external

resources and environmental conditions that might be available to

some children in curtailing the severity of their trauma. In addition,

Finkelhor (1987) notes the following limitations: (a) it provides a superficial explanation of the trauma of sexual abuse, (b) it does not

account for the anger, the worthlessness, and the self-blame that victims often feel, and (c) it incorrectly assumes that failure to integrate

the sexual abuse experience is the problem. Finkelhor (1987) suggests

that PTSD involves an over-integration of the experience whereby,

the victim transfers the behavior learned in the abusive situation and

indiscriminately applies it to other situations.

From the standpoint of traditional psychodynamic theory and child

development, the mother as the primary caretaker, is perceived as the

main source of psychopathology (Waites, 1993). Furthermore, the emphasis on the development of psychopathology during the first few

years ignores the reality of abuse occurring over the life span. It also

bypasses the role and contribution of fathers and family dysfunction

in the perpetuation of sexual abuse (Waites, 1993).

The Trauma Learning Model

Based on the tenets of psychodynamic formulations, information theory, and theories of stress response syndromes (Hartman & Burgess,

1988), this model describes how the victimized child processes information about sexual abuse. The four major phases include: pretrauma, trauma encapsulation, disclosure, and post-trauma phases.

Such factors as the child's personality, developmental stage, and

the coping/defensive mechanisms are important considerations. This

model also explains how general anxiety symptoms emerge as the

child attempts to process the offender's behavior and the continued

abuse (Hartman & Burgess, 1988). Of equal importance is the place of

secondary learning. That is, what happens if the child discloses/con-

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

81

ceals the abuse? The resulting behavioral responses can include a

number of possible patterns such as integrated, anxious, avoidant,

disorganized, and aggressive.

A strength of this model is its inclusion of multiple factors that

contribute to the child's conceptualization and processing of the

abuse experience. Recognition of developmental stages and the various stages of information processing can assist in identifying the

child's behavioral symptoms and strengths. The potential pattern of

response also provides a guide for enhancing assessment procedures

and treatment planning. If a pre-adolescent and adolescent were

abused by the same individual, cognitive, emotional, social, and personality differences need to be accounted for. In this model, attention is given to the child's perceptions and behavioral responses. Unfortunately, information is lacking regarding how these responses

are shaped by the nature and extent of the abuse, characteristics of

the perpetrator, the relationship of the perpetrator to the child, role

of others (e.g., teachers, counselors, social services workers) and the

role of social support. Consequently, this model would benefit from

expanding its present framework to examine the cognitive, social,

emotional, and academic ramifications of abuse.

The Social Learning Model

According to this model, what a child learns from being sexually abused

is mediated through social learning processes (Bandura, 1969, 1977).

The behavior of the offender can be viewed as,"... a form of instrumental aggression that produces sexual gratification" (Berliner & Wheeler,

1987). Sexual abuse exposes a child to social attitudes, beliefs, and

behaviors that are inappropriate and maladaptive. In addition, abuse

can interfere with the child's ability to learn healthy, adaptive ways of

being. The offender provides a modeling template for the child verbally,

behaviorally, and cognitively. For example, an abused child may come to

believe that sexual contact is an expression of love as well as a sign of

maturity. Additionally, the child may be led to believe that punishment

or threat of punishment will follow any refusal to cooperate sexually.

This process typically culminates in the child's perception of his or her

body as worthless, unacceptable, and vulnerable. Being a good child

becomes directly associated with obeying the requests or commands of

the offender.

The social learning model offers a reasonable framework for understanding some of the contextual factors pertaining to sexual abuse.

82

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

For children who are able to report the abuse to a supportive adult,

who in turn instigates corrective action, the potency of the maladaptive learning may be reduced. This critical aspect is absent in the

social learning model. Furthermore, this model does not account for

children who exhibit a capacity to reject erroneous messages conveyed by the offender. In the counseling session, for example, there

are children who realize their innocence while acknowledging the

pathological behavior of the offender.

Contrary to the suppositions of social learning theory, children

are not equally vulnerable. Factors such as: the age of the child,

supportive influences, and the cognitive and social capabilities that

mitigate maladaptive learning need to be addressed. An additional

shortcoming of this theory pertains to the underlying perception of

the offender's behavior and influence as negative and aggressive.

What needs to be considered however, are situations wherein the

child is not threatened or punished but rather offered rewards. This

model also falls short in distinguishing the possible differences between the experiences of those children who are abused one time

and those who experience multiple abuse.

The Psychosocial Model

This model stresses the role of differences in psychological outcome as

a function of the person's experience (Green, Wilson, & Lindy, 1985).

That is, individuals who are present at the same event (sexual abuse)

will have different outcomes because their experiences vary and the

unique characteristics that they bring to the situation are also distinct. An individual's ability to gradually assimilate the traumatic

event and re-stabilize are contingent upon personal characteristics

that involve perception, understanding, and emotional processing

(Green, Wilson, & Lindy, 1985). Within this framework, the individual's coping mechanisms, personality characteristics and any preexisting psychopathology are acknowledged. Moreover, the social environment in which the event and personal processing take place may

play an important part in the child's eventual adaptation (Green,

Wilson & Lindy, 1985). For instance, victimized children are likely to

have a healthier level of adjustment over time if they are supported

by a family who takes responsible action in reporting the abuse and

seeking appropriate counseling. This scenario is in stark contrast to

situations wherein a family responds in a non-supportive fashion,

blames and ostracizes the child, and dissuades contact with appropri-

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

83

ate professionals. In the latter scenario, the secrecy of the abuse is

maintained and the child has limited options to process the trauma

which they have experienced.

An advantage of this model is that it emphasizes individual characteristics that contribute to the psychological response and outcome with respect to post traumatic stress symptoms. Treatment

planning, in turn, can be tailored to address individual issues more

appropriately. In essence, this framework appears to be more person-centered in its approach to personal trauma. The interactive nature of this model is better suited to understanding the role of environmental factors, cognitive processing, recovery environment, and

individual characteristics in diminishing or exacerbating post traumatic stress outcome.

An overview of the aforementioned models demonstrates the need

for further examination in several areas. For example, child vulnerability tends to be generalized and as a result, individual uniqueness

warrants consideration. Additional attention is also required in the

areas of internal resources (e.g., child resiliency) and external resources (e.g., parental support and corrective measures). Furthermore, the varying degrees of symptomatology must be accounted for,

and situational versus multiple abuse discussed. Within the psychosocial model however, individual coping mechanisms and individual

characteristics are acknowledged, thus providing inroads for conceptualization and individual treatment plans.

Behavioral/Cognitive Models

The Behavioral Model

The application of the behavioral model to conceptualize PTSD is

based on two-factor learning theory (Lyons, 1987). Instrumental/operant conditioning and classical/Pavlovian theories constitute this

model. In classical conditioning, the traumatized individual encounters reflexive distress as a result of the threatening aspects of the

traumatic event (unconditioned stimuli). The presence of other neutral cues (conditioned stimulus) at the time of the trauma become

classically conditioned, thereby eliciting anxiety. Thus, if a young girl

is sexually abused by a teenage male who was entrusted with her

care, she may experience feelings of fear and anxiety when in his

presence. Such fear and anxiety may become heightened in situations

84

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

that resemble the incident of abuse (e.g., nighttime, in the park alone

together). As the process of generalization and/or higher order conditioning ensue, the youngster might experience feelings of anxiety in

response to persons or situations that are only remotely connected to

the original abuse context (Berliner & Wheeler, 1987). For example,

she may fear going to the park, being alone with a male, or being in

the care of those aside from trusted adults. Inherently neutral cues

become classically conditioned in such a way that they also become

associated with the traumatic event. Anxiety is elicited even though

these cues do not represent inherent danger or harm.

In instrumental/operant conditioning, the individual learns to voluntarily behave in a way that elicits a desired consequence, which is

usually relief from anxiety (Lyons, 1987). The individual learns to

avoid or escape from the trauma-associated cues (both unconditioned

stimulus and conditioned stimulus) as a means of reducing anxiety.

What begins as an experience with one individual (the perpetrator)

becomes the basis for overgeneralized responses to others. Berliner

and Wheeler (1987) state that, ". . . as the processes of generalization

and/or higher-order conditioning proceed, the child might experience

anxiety in the presence of persons or lessened situations far removed

from the initial abusive experiences" (p. 419). Using the previous example, the young person may try to avoid contact with the other male

teenagers and protest whenever she is to be supervised by someone

whom she deems untrustworthy. These attempts are designed to minimize or reduce exposure to trauma-related cues and decrease personal anxiety.

According to the behavioral framework some symptoms are regarded as involuntary anxiety responses which are associated with

the UCS/CS (e.g., sleep disturbances, startle responses and nightmares) while other symptoms (e.g., emotional numbing and behavioral avoidance) are seen as instrumentally conditioned avoidance

response (Lyons, 1987). Such an explanation is plausible in some

situations. This model provides an account of how abused children

make adaptive attempts to manage their anxiety. It also accentuates

the potential for this process to contribute to maladaptive and debilitating responses. However, this account provides only one possible

explanation. Research indicates that individual differences in response to childhood sexual abuse relates to three mediating variables: severity of the abuse, availability of support, and attributing

styles with respect to the cause of negative life events (Wolfe, Gentile & Wolfe, 1989). The emphasis on the behavioral manifestations

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

85

of the child's fear and anxiety, as well as avoidant strategies, limits

examination regarding other factors such as: the cognitive level of

the child, age, social maturity, social support, and how developmental factors play a role in diminishing the level of anxiety and avoidance responses. Furthermore, what needs to be considered are the

differences in the behavioral responses between infants, pre-school

children, elementary school children, and adolescents. This model

fails to provide an explanation of why some children who have been

victimized do not display debilitating levels of emotional numbing or

sleep disturbances while others do. By underscoring the behavioral

components of sexual trauma in childhood, other critical issues such

as trust, social relationships, self concept, intimacy, body image and

self-esteem are not addressed in this model.

The Cognitive Impact Model

Sexual abuse may not only shape a child's behavioral effects but it may

also impact their values, beliefs and attitudes. Janoff-Bulman (1985)

postulates that PTSD symptoms can be traced to a traumatic event

that can dismantle the basic assumptions about self, the world, and

reality in general. The victimization experience disturbs the personal

theories that otherwise assist in goal setting, planning, and ordering

behavior. Moreover, the experience of trauma does not provide room

for continued conformity to previously held expectations and assumptions. A child's cognitions based on prior experience can be severely

challenged and may no longer be viable (Janoff-Bulman, 1985). A boy

who has enjoyed years of companionship, social activities, and learning opportunities with his mother's boyfriend may become generally

withdrawn and isolated after being abused by this individual. No

longer does the youngster believe that his childhood is one of safety but

instead, grapples with a sense of insecurity and perceives older males

as exploitative and untrustworthy.

Within this framework, Janoff-Bulman (1985) highlights three particular types of assumptions that are affected. First, there is the belief in personal invulnerability. The aftermath of trauma may result

in the individual's realization that vulnerability and a sense of danger

are the new realities. In other words, the world is no longer a place of

safety and security. Second, there is a basic belief that the world is

just, orderly, and optimally benign. Being victimized often does not

make sense and defies the belief in social justice. The aftermath of

victimization involves the replacement of these assumptions with per-

86

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

ceptions of danger, threat, self-questioning, and insecurity. The third

assumption pertains to the notion that individuals tend to regard

themselves as essentially decent and worthy. Such self-perceptions

and self-images are challenged. The adoption of a negative self-image

is evident in the experience of helplessness, self-blame, and powerlessness. According to Janoff-Bulman (1985), this state of disequilibrium is marked by symptoms that are characteristic of PTSD. The

re-establishing of an assumptive world that includes the victimization

experience is a vital part of the recovery process.

This model presents only a partial description of what happens to

many sexual abuse victims, and considers only some of the cognitive

impacts (e.g., I must be bad because something bad happened to me).

As suggested by Finkelhor (1987, 1990), some of the characteristic

sexual abuse symptoms, such as sexualized behavior do not fit. This

framework also raises the question of whether PTSD theories that

pertain to adults can be superimposed onto a child's experiences of

sexual trauma, given the significant differences in cognitive development and processing of information. Consideration needs to be rendered to the age and cognitive abilities of the child. That children

believe that they are safe and secure in the world is not a universal

assumption of all children, at all times prior to sexual abuse. The

same can be said of the assumption that the world is basically a benign place. Little is said in this model about the prior experiences

that can often impact the maintenance and change of cognitive assumptions. For some children, the abuse experience involves a series

of indoctrinations whereby the perpetrator uses influence, power, and

coercion to convince the child that he or she is safe and secure or that

the sexual abuse is benign. The compelling nature of the abuse relationship may result in these assumptions remaining acceptable for

the child, however temporary. The child is presented with a rational

explanation of the abuse thus, effectively reinforcing his or her indoctrination (Waites, 1993). This model does not accommodate such an

explanation.

Although it is proposed that children generally assume a sense of

security, safety, and personal worthiness, there is no mention of how

youngsters actually arrive at these conclusions. To assume that children begin with and pursue such an untainted life seems simplistic

and unrealistic. As such, the presence or absence of prior victimization needs to be recognized. According to Boney-McCoy and Finkelhor

(1995) the extent of impact and symptoms of sexual abuse may be

related to the experience of prior victimizations (sexual and non-sex-

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

87

ual). These authors further note that additional research is needed

regarding the impact of indirect victimization on perceptions of vulnerability and also on other factors that may link this experience

with subsequent child sexual abuse.

The area of cognitive development requires attention since a child's

thinking process could influence his or her interpretation of sexual

abuse and the possible symptoms that are later manifested. A closer

examination of age differences, sense of responsibility, guilt, and the

relationship with self abuse or destructive behavior might provide

valuable information regarding some of the intervening variables that

influence the effects of abuse (Kendall-Tackett, Williams & Finkelhor,

1993). For example, research suggests that family conflict/cohesion,

and support of the child, are factors that are significantly related to

the extent of behavior problems in sexually abused children (Friedrich, Beilke & Urquiza, 1987). Lastly, PTSD-related symptoms represent only a small proportion of the symptomatology that is often observed (Kendall-Tackett, Williams, & Finkelhor, 1993) in childhood

sexual abuse. Therefore, a wider scope of post-assault functioning

needs to be explored.

The Cognitive Behavioral Model

This model shares some overlap with the cognitive impact model as

outlined by Janoff-Bulman (1985). The effects of childhood sexual

abuse may be manifested in nightmares, fears, flashbacks, hyper-vigilance, and other aversive feelings and intrusive thoughts which, in

turn, become linked with memories of the abuse or certain evocative

stimuli (Berliner, 1991; Scott & Stradling, 1992). This model accommodates the PTSD framework while punctuating the negative implications that such experiences can have on self-esteem, self-concept,

trust in others, sexuality, and a sense of personal efficacy. The dynamics of sexual abuse often are associated with inaccurate beliefs

about the victimization experience and the whys [italics added] of

such an event. Particular attention needs to be paid to modelled or

reinforced behaviors stemming from the abuse. Furthermore, it is essential to consider how the child processes the meaning of the abuse

and the extent to which there might be some identification with the

aggressor. According to this model, cognitive adjustment is a significant variable (Berliner, 1991; Wolfe, Gentile, & Wolfe, 1989). The possible negative attributions that may evolve into an attributional style,

and the result of lowered self-esteem and depression also warrant

88

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

careful consideration (Berliner, 1991). An abused child may subscribe

to a specific belief system, however irrational, because it provides a

protective shield against uncontrollable shock or stress. For example,

a child may rationalize the abusive behavior of a parent by believing

that the abuse was for their own good or that people who love him or

her have to hurt them.

According to Goddard and Stanley (1994) the responses of a sexually abused child to the abuser has parallels with the Stockholm syndrome. The child is placed in a helpless and vulnerable position and,

like the hostage, begins to turn to and accept the explanations of the

offender. In order to survive, the child may begin to alter his or her

beliefs about self and/or the abuser. Beliefs of unworthiness and being

deserving of punishment may be incorporated in the child's cognitive

set. Furthermore, the child may become more accepting of the offender's rationale for the abuse and even develop positive feelings toward the abuser and his or her behavior (Goddard & Stanley, 1994).

Similar to other theoretical models, the cognitive-behavioral framework provides an explanation which has merit and is perhaps fitting

for some sexual abuse victims. Specifically, this model accounts for

situations in which the child does indeed experience change in his or

her own belief systems that are aligned with the abuser. However,

this framework does not accommodate exceptions. Additionally, by focusing on the cognitive experiences resulting from the abuse, other

critical experiences such as emotional reactions, changes in sleeping

patterns or academic functioning and difficulties in concentrating are

not discussed.

When carefully examining this model, questions regarding several

pertinent issues emerge such as: (a) the self efficacy and survival

strategies used by resilient children to counter or diminish the abuser's beliefs, (b) the ages of children who are likely to be most cognitively vulnerable, (c) the significance of other factors with respect to

the child's cognitive experiences of the abuse (e.g., relationship of perpetrator to child, characteristics of the victim, developmental stage of

the child, frequency/duration/intensity of the abuse, and family dynamics) and finally, (d) variables that contribute to a more favorable

cognitive outcome. According to Kiser, Heston, Millsap, and Pruitt

(1991) the development or prevention of PTSD in children is linked to

many contextual factors. The cognitive-behavioral model does not

consider some of these important elements.

The models that fall within the preceding category need to better

distinguish among age groups and to accommodate exceptions (e.g.

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

89

resilient children). Furthermore, significant differences in cognitive

development and processing of information, requires elaboration. Due

to a focus on the individual, important contextual factors appear to be

overlooked. In an effort to advance these models, critical issues (e.g.

trust, self-concept, self-esteem) and emotional reactions need to be

considered.

Formative Models

The Developmental Model

The developmental view posits that a child moves through a series of

progressive developmental stages. Within each stage there are salient

issues linked to developmental tasks that need to be sufficiently resolved in order for the child to adapt to his or her environment.

The manner in which PTSD is manifested hinges on the developmental stage of the individual at the time of the trauma (Goodwin,

1984; Wilson, Smith, & Johnson, 1985). In general, clinical reports

support the assumption that the impact of trauma will be a function

of the developmental stage of the child (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986;

Lyons, 1987; Monahon, 1993). In a study of pre-school, school-age,

and adolescent children who had been sexually abused, it was found

that disturbed pre-schoolers displayed cognitive impairment and severe stress reactions (Gomes-Schwartz, Horowitz & Sauzier, 1985).

Furthermore, these researchers found fearfulness, destructiveness,

and aggression to characterize school-age children while adolescents

showed signs of depression, anxiety, and obsessive thoughts. Age-appropriate developmental tasks are believed to be disrupted by sexual

stimulation and pre-occupation with the sexual relationship while legitimate prior developmental needs remain unaddressed (Tharinger,

1990). Based on the belief that the indicators of trauma vary according to the child's age, developmental guidelines have been established

to summarize the signs of trauma according to what typically appears

for children ranging from infancy to age 18 years (Monahon, 1993).

Terr (1991) outlines four characteristics that are of particular relevance in traumatized children regardless of the child's age at the time

of abuse. These include: (a) strongly visualized or otherwise repeatedly perceived memories, (b) repetitive behaviors, (c) trauma-specific

fears, and (d) changed attitudes about people, aspects of life, and the

future. It appears that age shapes the child's experience of trauma

90

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

and his or her subsequent reactions. For example, Terr (1991) contends that with the exception of children under the age of two and one

half years to three years of age, ". . . almost every previously untraumatized child who is fully conscious at the time that he or she

experiences or witnesses one terrible event demonstrates the ability

to retrieve detailed and full memories afterward" (p. 14).

Eth and Pynoos (1985) note that children, according to age, are

more or less susceptible to the effects of intrapsychic, familial, and

societal pressures. Another developmental concern is the influence of

the processes of trauma resolution with other tasks of childhood such

as play, school work, and interpersonal relationships. With respect to

overt sexual behavior problems, Tharinger's (1990) review of previous

studies has resulted in the tentative conclusion that the nature of the

overt sexual behavior problems manifested by sexually abused children varies according to age. Further research and investigation

needs to be conducted into children's coping processes, their developmental determinants, and trauma mastery so that vulnerable and resilient children can be better understood (Pynoos & Eth, 1985).

The developmental perspective enables the trauma of childhood

sexual abuse to be examined at a specific age or point in time. For

example, a youngster can be assessed for the presence of PTSD symptoms one year following the abuse experience. However, this framework also needs to address the developmental perspective over an

extended period of time in order to account for what happens to sexually abused children in terms of recovery.

Since there are many facets of development that are important considerations, the developmental framework needs to carefully examine

the effects of sexual abuse on cognitive and social development. At

each developmental stage, children's thoughts, emotions, and behaviors undergo change. As such, this framework needs to account for

these changes and the impact of sexual abuse experiences at each

stage (Kendall-Tackett, Williams & Finkelhor, 1993). Since the mid1980's, the impact of sexual abuse pertaining to the sexual functioning of children has been empirically researched (Tharinger, 1990). A

developmental approach also needs to include the multiple dimensions that contribute to and impede child development following sexual abuse experiences. Mediating variables need to be included in the

assessment and treatment process. Issues that merit serious consideration include: (a) the nature and extent of the child's emotional relationship with the perpetrator; (b) change in the status of the victimperpetrator relationship over time; (c) the status of the child's sense of

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

91

self-efficacy and adult influence that has been instrumental in this

process; (d) the victim's relationship to peers, authority figures and

other adults; (e) the child's experience of his or her sense of self; (f)

the child's beliefs about self, the abusive event, the offender and the

future; and (g) the changes that occur with time and those factors

that influence the course of these changes.

Longitudinal research regarding developmental issues might also

elucidate important adjustment factors such as how children's coping

skills change with increasing age and how children re-conceptualize

their abuse experience over time (Black, Dubowitz & Harrington,

1994). This knowledge might also provide useful information regarding what factors might place a child at high risk with respect to the

course of PTSD.

On a cautionary note, theoreticians and clinicians need to be prudent regarding strict adherence to the developmental criteria outlined

in this model. Acknowledgment of individual differences that characterize young victims is crucial. Otherwise, those who do not meet particular age-appropriate criteria may be overlooked or inaccurately assessed and diagnosed. Understanding individual differences or factors

that contribute to resilience to sexual abuse might provide valuable

information regarding a child's capacity to thrive. A comprehensive

model must provide multi-dimensional markers that guide clinicians

and researchers as they examine the short-term and long-term implications of childhood sexual abuse.

The Traumagenic Dynamics Model

This model originated as a response to the limitations of applying the

PTSD model to sexual abuse. Finkelhor (1987) underscores the problems that plague the PTSD model and notes that it only addresses

specific symptoms and victims. A more useful model would incorporate some aspects of the PTSD model and aspects of sexual abuse that

are not identifiable under the rubric of PTSD.

In an attempt to account for the effects of sexual abuse, Finkelhor

and Browne (1985, 1988) propose a comprehensive model that presumes that the experience of sexual abuse can have different effects.

Suggested in this model is the idea that there are a variety of different dynamics to account for the variety of different types of symptoms. This approach stresses the importance of viewing the trauma of

sexual abuse as resulting from the abuse itself and the conditioning

process that exists prior to and after the abuse. The effects of sexual

92

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

abuse depend on the character of the abuse and on four main areas of

children's development including ability to trust in personal relationships, self-esteem, sense of ability to affect the world, and sexuality

(Finkelhor, 1990).

According to this model there are four trauma-causing factors or

traumagenic dynamics that correspond to the four areas of children's

development. The four traumagenic dynamics are: betrayal, stigmatization, powerlessness, and traumatic sexualization. These dynamics

result from the abuse experience, the child's level of pre-abuse adjustment, and the impact of others' responses following the disclosure of

the abuse. As organizational constructs, the four dynamic qualities

outline how the abuse process alters the abused child's cognitive and

emotional interactions with the world, and in turn, effect the nature

and extent of ongoing trauma by distorting the child's self-concept,

world view, and affective capacities (Tharinger, 1990).

A strength of this model is the incorporation of the PTSD diagnostic

category as one distortion (affective capacities) among others (Finkelhor, 1987). As such, affective and cognitive distortions are included. A more complex assessment of the potential for trauma is

made possible by emphasizing the extent to which the abuse was

traumatically sexualizing (e.g., what was the duration of the experience) and the level of stigmatization resulting from the abuse (e.g.,

the degree to which others blamed the child after disclosure). This

model also provides a conceptualization of sexual abuse that goes beyond an event by stressing the involvement of an ongoing process

(Finkelhor, 1987). Attention is therefore rendered to the traumagenic

dynamics before, during, and after the offense (Finkelhor, 1987). For

example, some children may experience their greatest sense of powerlessness during the sexual act. Other children may find the disclosure process renders them most powerless.

The dynamics outlined are also specific to sexual abuse and do not

occur in other childhood traumas such as parental death or psychological maltreatment. By addressing sexual abuse exclusively, rather

than as one of several trauma types, a more comprehensive picture of

the course of sexual traumatization is possible. Of the models outlined, the traumagenic dynamics model holds promise with respect to

understanding the multiple factors that shape the sequelae of abuse

and recovery repercussions.

A review of the preceding two theories indicates that additional research is required regarding children's coping processes, developmental determinants, and trauma mastery to better understand vulner-

PATRICK J. MORE1SSETTE

93

able and resilient children. There is also a need to examine the effect

that sexual abuse has on the social and cognitive development of a

child at various stages. The multiple dimensions (e.g., relationship

with perpetrator, sense of self) that contribute to and impede child

development following the abuse warrants attention. Further longitudinal research pertaining to the recovery process would also add

substantially to the existing data.

PTSD in Childhood Sexual Abuse: Merits and Limitations

Finkelhor (1987, 1990) highlights the salutary effects that the PTSD

framework has had on the phenomenon of sexual abuse and includes:

(a) the provision of a clear label and description of a phenomenon that

victims of sexual abuse suffer from, (b) a perspective that sexual

abuse is a syndrome with an etiological core rather than simply a list

of symptoms, (c) assistance to researchers of different trauma areas

to study sexual abuse as another manifestation of their subject matter, and (d) the disempowering stigma that victims often experience

because of the inclusion of the effects of sexual abuse as a form of

PTSD.

Another advantage of the PTSD diagnosis is the notion that it normalizes the presenting problems for clients and their families, and

depathologizes the survivor (Dolan, 1991; Kirschner, Kirschner, &

Rappaport, 1993). As a diagnostic category, it is broad enough to encompass the host of symptoms often associated with sexual abuse

(Courtois, 1992). Moreover, the drawing of parallels between sexual

abuse symptoms and the causes of PTSD such as natural disasters or

car accidents helps individuals to make sense of their experiences. A

greater sense of control may emerge after a PTSD diagnosis is provided. This diagnosis also recognizes that symptoms can be predictable consequences of external events such as sexual abuse (Blume,

1990). According to Friedrich (1990) a PTSD diagnosis enables clinicians to give voice and raise awareness to the prevalence of child sexual abuse by proclaiming, "There are bad things happening to our

children; take notice [italics original], in the same manner that we

were forced to notice PTSD in Vietnam veterans" (p. 23).

The idea that sexual abuse trauma is a form of PTSD suggests an

association between sexual abuse and the understanding of other

kinds of trauma. In terms of the counseling process, the PTSD diagnostic framework allows for the identification of specific behaviors

94

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

that may be important to address in therapy. The application of PTSD

therapies for other traumas can also offer a blueprint or model for

sexual abuse treatment (Finkelhor, 1990). Advocating the need to refocus on disruptive factors rather than categorizing clients, there is a

need to re-orient clinical treatment to how and why people become

organized (or disorganized) around past experiences.

There is the existing view that PTSD remains the best available

psychiatric framework for understanding the effect of abuse trauma

(Blume, 1990). The limitations inherent in this model however warrant ongoing investigation and further refinement. The PTSD framework appears to be forced upon the symptoms of sexual abuse as the

emphases are different (Finkelhor, 1987, 1990). In addition, PTSD

symptoms are absent for many victims of sexual abuse. For example,

the concept of PTSD does not help in understanding children who

experience abdominal pain or youngsters who bully their peers. Finkelhor (1987, 1990) warns of the inherent dangers in relying on PTSD

for diagnosing sexual abuse. For example, an erroneous conclusion

could be drawn that in the absence of sufficient symptoms to warrant

a PTSD diagnosis, a child may be perceived as being less traumatized

by the sexual abuse.

With the emphasis on assessing for pathology and symptoms, the

PTSD diagnosis may, ". . . fail to acknowledge the admirable survival

spirit and inevitability of the emotional and behavioral consequences

it describes" (Blume, 1990, p. 78). Consequently, the PTSD diagnosis

can potentially bypass human feelings and life, and overemphasize

symptoms instead. The seductiveness (Friedrich, 1990) and popularity of this framework has also resulted in clinicians randomly applying it to children who have experienced other traumas such as

family alcoholism and with children who are verbally or physically

abused (Blume, 1990).

In a comprehensive update on the early and long-term effects of

child sexual abuse, Finkelhor (1990) further highlights some of the

objections to the PTSD formulation. First, he argues that the PTSD

conceptualization seems narrow as victims of sexual abuse often experience more than symptoms that fall under this diagnostic description. Second, the PTSD conceptualization fails to consider the cognitive distortions resulting from sexual abuse that include areas such

as self-worth, family relations, and sexual behavior. Instead, there

appears to be an overemphasis on the affective realm and the constriction of affect. Third, this framework provides little guidance with

respect to individuals who may encounter problems that are not explicitly categorized as PTSD symptoms.

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

95

Furthermore, the theory behind PTSD fails to account for the possibility that abused children who do not experience PTSD as adults are

less traumatized. In many ways, the PTSD model is inadequate in its

explanation of sexual abuse. The inherent danger in solely viewing

sexual abuse trauma as a PTSD classification is that the more serious

effects may be overlooked (Finkelhor, 1990). In a review of the literature pertaining to the applicability of the PTSD diagnosis in childhood sexual abuse, Rowan and Foy (1993) offer counter-arguments to

Finkelhor's (1990) position. The relevant points outlined include: (a)

the purpose of a diagnostic framework is to classify the main features

of a person's difficulties, not to explain specific details; (b) there are

diagnostic limitations inherent in Finkelhor's model; and (c) contrary

to Finkelhor's (1987) suggestion that PTSD lacks sufficient acknowledgment of cognitive issues, general cognitive difficulties are considered in the symptom classifications (Rowan & Roy, 1993).

Conclusion

As demonstrated in the literature, attempts have been made to effectively utilize a PTSD diagnosis with children who have been sexually

abused. Further investigation into this practice however, reveals that

the PTSD diagnosis is not as straightforward as one might initially

anticipate. The difficulty in providing a definite PTSD diagnosis is

complicated by a number of complex issues and queries.

Despite the recognized advantages of a PTSD diagnosis (e.g., a

clear label and description of a phenomenon, symptom prediction and

normalization), it is not without limitations. For instance, the uncertainty regarding what actually constitutes a traumatic event exemplifies one such pertinent issue. In addition, questions around resiliency and why some children exhibit PTSD symptoms, while others

do not, also persist. It appears that the ongoing challenge is to discover a theoretical model that is broader than PTSD, while distinguishing sexual abuse from other childhood traumatic events.

Clearly, there are a growing number of theoretical frameworks that

provide conceptualizations of post-traumatic stress in sexually abused

children. Needless to say, it would be premature for the professional

to uncritically adopt one particular framework at such an early point.

It has only been within the past ten years that the field of sexual

abuse research has become more sophisticated and has moved beyond

the examination of mere symptoms in an effort to conceptualize the

impact of sexual abuse (Finkelhor, 1990). While there is considerable

96

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT SOCIAL WORK JOURNAL

acceptance of the conceptualization that the impact of sexual abuse

can be accounted for under the PTSD nosology, the number of debates

on the efficacy of this model is increasing.

References

Bandura, A. (1969). Principles of behavior modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart &

Winston.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Beitchman, J., Zucker, K., Hood, J., daCosta, G., Akman, A., & Cassavia, F. (1992). A

review of the short term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 15,

537-556.

Berliner, L. (1991). Cognitive therapy with a young victim of sexual assault. In W.

Friedrich (Ed.), Casebook of sexual abuse treatment, (pp, 93-111). New York: Norton.

Berliner, L., & Wheeler, J. (1987). Treating the effects of sexual abuse on children.

Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2, 415-434.

Black, M., Dubowitz, H., & Harrington, D. (1994). Sexual abuse: Developmental differences in children's behavior and self-perception. Child Abuse & Neglect, 18, 85-95.

Blume, S. (1990). Secret survivors: Uncovering incest and its after effects in women.

New York: Wiley.

Boney-McCoy, S., & Finkelhor, D. (1995). Prior victimization: A risk factor for child

sexual abuse and for PTSD-related symptomatology among sexually abused youth.

Child Abuse & Neglect, 19, 1401-1421.

Browne, A., & Finkelhor, D. (1986). Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 66-77.

Courtois, C. (1992). The memory retrieval process in incest survivor therapy. Journal of

Child Sexual Abuse, 1, 15-31.

Dolan, Y. (1991). Resolving sexual abuse: Solution-focused therapy and Ericksonian

hypnosis for adult survivors. New York: Norton.

Eth, S., & Pynoos, R. (1985). Developmental perspective on psychic trauma in childhood. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Trauma and its wake: The study and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (pp. 36-52). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Finkelhor, D. (1987). The trauma of child sexual abuse: Two models. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2, 348-366.

Finkelhor, D. (1990). Early and long-term effects of child sexual abuse: An update.

Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 21, 325-330.

Finkelhor, D., & Browne, A. (1985). The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A

conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55, 530-541.

Finkelhor, D,, & Browne, A. (1988). Assessing the long-term impact of child sexual abuse:

A review and conceptualization. In L. E. Walker (Ed.), Handbook on sexual abuse of

children: Assessment and treatment issues (pp. 55-71). New York: Springer.

Friedrich, W. (1990). Psychotherapy of sexually-abused children and their families. New

York: Norton.

Friedrich, W., Beilke, R., & Urquiza, A. (1987). Children from sexually abusive families:

A behavioral comparison. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2, 391-402.

Gelinas, D. (1983). The persisting negative effects of incest. Psychiatry, 4, 312-332.

Goddard, C., & Stanely, J. (1994). Viewing the abusive parent and the abused child as

captor and hostage. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 9, 258-269.

Goodwin, J. (1984). Incest victims exhibit post-traumatic stress symptoms. Clinical

Psychiatry News, 12, 13.

PATRICK J. MORRISSETTE

97

Gomes-Schwartz, B., Horowitz, J., & Sauzier, M. (1985). Severity of emotional distress

among sexually abused pre-school age and adolescent children. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 36, 503-508.

Green, B., Wilson, J., & Lindy, J. (1985). Conceptualizing post-traumatic stress disorder: A psychosocial framework. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Trauma and its wake: The

study and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (pp. 53-69). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Hartman, C., & Burgess, A. (1988). Information processing of trauma: Case application

of a model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 3, 443-457.

Herman, J. (1995). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated

trauma. In G. Everly & Lating, J. (Eds.), Psychotraumatology: Key papers and core

concepts in post-traumatic stress (pp. 87-100). New York: Plenum.

Herman, J. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violencefrom domestic

abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books.

Horowitz, M. (1976). Stress response syndromes. (2nd ed.), New Jersey: Jason Aronson.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1985). The aftermath of victimization: Rebuilding shattered assumptions. In C. R Figley (Ed.), Trauma and its wake: The study and treatment of

post-traumatic stress disorder (pp. 15-34). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Kendall-Tackett, K., Meyer-Williams, L., & Finkelhor, D. (1993). Impact of sexual

abuse in children: A review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 164-180.

Kirschner, S., Kirschner, D., & Rappaport, R. (1993). Working with adult incest survivors: The healing journey. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Kiser, L., Heston, J., Millsap, P., A. & Pruitt, D. (1991). Physical and sexual abuse in

childhood: Relationship with post-traumatic disorder. Journal of the American

Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 776-783.

Lyons, J. (1987). Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A review

of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 8, 349-356.

Mannar, C., & Horowitz, M. (1988). Diagnosis and phase-oriented treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In J. Wilson, Z. Harel & B. Kahana (Eds.), Human adaptation to extreme stress from the Holocaust to Vietnam (pp. 81-102). New York:

Plenum Press.

Monahon, C. (1993). Children and trauma: A parent's guide to helping children heal.

New York: Lexington Books.

Rosenfeld, A., Nadelson, C., Krieger, M., & Backman, J. (1979). Incest and sexual abuse

of children. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 16, 827-339.

Rowan, A., & Foy, D. (1993). Post-traumatic stress disorder in child sexual abuse survivors: A literature review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6, 3-22.

Scott, M., & Stradling, S. (1992). Counseling for post-traumatic stress disorder. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Terr, L. (1991). Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 10-20.

Tharinger, D. (1990). Impact of child sexual abuse on developing sexuality. Professional

Psychology: Research and Practice, 21, 331-337.

Waites, E. (1993). Trauma and survival: Post-traumatic and dissociative disorders in

women. New York: Norton.

Wilson, J., Smith, W., & Johnson, S. (1985). A comparative analysis of post-traumatic

stress disorder among various survivor groups. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Trauma and

its wake: The study and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (pp. 142-172).

New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Wolfe, V., Gentile, C., & Wolfe, D. (1989). The impact of sexual abuse on children: A

PTSD formulation. Behavior Therapy, 20, 215-228.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Raphex 2010 PDFDocument26 pagesRaphex 2010 PDFcarlosqueiroz7669100% (3)

- Pragmatic Existential TherapyDocument16 pagesPragmatic Existential Therapysolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Amls Als Pretest Version 1.11Document10 pagesAmls Als Pretest Version 1.11ArlanosaurusNo ratings yet

- Orthodontics and Bioesthetics: A Perfect SymbiosisDocument22 pagesOrthodontics and Bioesthetics: A Perfect Symbiosishot_teeth100% (1)

- Greek Philosophy and PsychotherapyDocument8 pagesGreek Philosophy and PsychotherapytantravidyaNo ratings yet

- Applications of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy in Suicide Prevention PDFDocument13 pagesApplications of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy in Suicide Prevention PDFsolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Art - The Psychological Complexities of Chronic Illness and ImpairmentDocument13 pagesArt - The Psychological Complexities of Chronic Illness and Impairmentsolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Art - Motivational Interviewing in Medical SettingsDocument19 pagesArt - Motivational Interviewing in Medical Settingssolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- A Solution-Focused Intervention With A Youth in A Domestic Violence Situation - Longitudinal EvidenceDocument11 pagesA Solution-Focused Intervention With A Youth in A Domestic Violence Situation - Longitudinal Evidencesolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- A Solution-Focused Approach To Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy - Toward A Theoretical IntegrationDocument22 pagesA Solution-Focused Approach To Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy - Toward A Theoretical Integrationsolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- A Solution-Oriented Approach To Working With Juvenile OffendersDocument12 pagesA Solution-Oriented Approach To Working With Juvenile Offenderssolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Systems and Solutions - The Discourses of Brief TherapyDocument18 pagesSystems and Solutions - The Discourses of Brief Therapysolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Knutson-Tao Honeycomb IDocument36 pagesKnutson-Tao Honeycomb IRamiro LafuenteNo ratings yet

- Working With People Who Are Violent To Their Partners - A Safety Building ApproachDocument14 pagesWorking With People Who Are Violent To Their Partners - A Safety Building Approachsolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Forgiveness - Developing A Model For Empowering Victims of Sexual AbuseDocument15 pagesTherapeutic Forgiveness - Developing A Model For Empowering Victims of Sexual Abusesolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- The Contributing Factors of Change in A Therapeutic ProcessDocument10 pagesThe Contributing Factors of Change in A Therapeutic Processsolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Therapist Positioning and Power in Discursive Therapies - A Comparative AnalysisDocument17 pagesTherapist Positioning and Power in Discursive Therapies - A Comparative Analysissolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- What Do You Think About What The Team Said - The Solution-Focused Reflecting Team As A Virtual Therapeutic CommunityDocument14 pagesWhat Do You Think About What The Team Said - The Solution-Focused Reflecting Team As A Virtual Therapeutic Communitysolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Arthur C. Bohart - The Client Is The Most Important Common Factor - Clients' Self-Healing Capacities and Psychotherapy 2000Document23 pagesArthur C. Bohart - The Client Is The Most Important Common Factor - Clients' Self-Healing Capacities and Psychotherapy 2000Calin100% (1)

- Some Thoughts On Language Use in TherapyDocument9 pagesSome Thoughts On Language Use in Therapysolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Systemic Therapy - An OverviewDocument9 pagesSystemic Therapy - An Overviewsolutions4family100% (1)

- Solution-Focused Brief Therapy and The Kingdom of God - A Cosmological IntegrationDocument7 pagesSolution-Focused Brief Therapy and The Kingdom of God - A Cosmological Integrationsolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Solution-Focused Therapy in PrisonDocument15 pagesSolution-Focused Therapy in Prisonsolutions4family100% (1)

- Questions As Interventions - Perceptions of Socratic, Solution Focused, and Diagnostic Questioning StylesDocument26 pagesQuestions As Interventions - Perceptions of Socratic, Solution Focused, and Diagnostic Questioning Stylessolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Solution-Focused Therapy and Psychosocial Adjustment To Orthopedic Rehabilitation in A Work Hardening ProgramDocument10 pagesSolution-Focused Therapy and Psychosocial Adjustment To Orthopedic Rehabilitation in A Work Hardening Programsolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Resourceful Dialogues - Eliciting and Mobilizing Client Competencies and ResourcesDocument11 pagesResourceful Dialogues - Eliciting and Mobilizing Client Competencies and Resourcessolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- On The Ethics of Constructing RealitiesDocument11 pagesOn The Ethics of Constructing Realitiessolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Me and My Shadow - Therapy With Sexually Abused Pre-AdolescentsDocument14 pagesMe and My Shadow - Therapy With Sexually Abused Pre-Adolescentssolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Problem Definition in Marital and Family Therapy - A Qualitative StudyDocument21 pagesProblem Definition in Marital and Family Therapy - A Qualitative Studysolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Parent-School and Community Partnerships in Children's Mental Health - Networking Challenges, Dilemmas, and SolutionsDocument14 pagesParent-School and Community Partnerships in Children's Mental Health - Networking Challenges, Dilemmas, and Solutionssolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- Mendenhall - Overcoming Depression in A Strange Land - A Hmong Womanâ S Journey in The World of Western MedicineDocument14 pagesMendenhall - Overcoming Depression in A Strange Land - A Hmong Womanâ S Journey in The World of Western Medicinesolutions4familyNo ratings yet

- PFOA in Drinking Water (Canada)Document103 pagesPFOA in Drinking Water (Canada)willfarnabyNo ratings yet

- Neurology Case ConferenceDocument64 pagesNeurology Case ConferenceAnonymous HH3c17osNo ratings yet

- Sa-Ahm Five Element AcupunctureDocument12 pagesSa-Ahm Five Element AcupunctureSivaramakrishnan GNo ratings yet

- Life Participation Approach To AphasiaDocument4 pagesLife Participation Approach To AphasiaViviana HerediaNo ratings yet

- Vertex Announces Positive Day 90 Data For The First Patient in The Phase 1 - 2 Clinical Trial Dosed With VX-880, A Novel Investigational Stem Cell-Derived Therapy For The Treatment of Type 1 DiabetesDocument3 pagesVertex Announces Positive Day 90 Data For The First Patient in The Phase 1 - 2 Clinical Trial Dosed With VX-880, A Novel Investigational Stem Cell-Derived Therapy For The Treatment of Type 1 Diabetesዘረአዳም ዘመንቆረርNo ratings yet

- Heart FailureDocument6 pagesHeart FailureAnthony Philip Patawaran CalimagNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument5 pagesNCPJalishia Mae DumdumaNo ratings yet

- Cefuroxime & AmoxicillinDocument6 pagesCefuroxime & AmoxicillinarifpharmjuNo ratings yet

- IstrazitiDocument19 pagesIstrazitiboris.duric0804No ratings yet

- Emotional and Behaviour DisorderDocument21 pagesEmotional and Behaviour DisorderBoingotlo Gosekwang100% (1)

- Bio-Medical Waste Management Rules 2016Document37 pagesBio-Medical Waste Management Rules 2016Shakeel AhmedNo ratings yet

- Functional Appliances Mode and Action I & RDocument46 pagesFunctional Appliances Mode and Action I & RIslam M. YahiaNo ratings yet

- List Medicinal Products Under Additional MonitoringDocument14 pagesList Medicinal Products Under Additional MonitoringTab101 WokingNo ratings yet

- Cataract: Care of The Adult Patient WithDocument43 pagesCataract: Care of The Adult Patient WithAnna Francesca AbarquezNo ratings yet

- Phobias: A Reasearch by Hamza Moatsim BillahDocument20 pagesPhobias: A Reasearch by Hamza Moatsim BillahSwiftPublishedDocsNo ratings yet

- Apa Paper For Mental HealthDocument13 pagesApa Paper For Mental Healthapi-648586622No ratings yet

- Managementof Postoperative Complicationsfollowing Endovascularaorticaneurysm RepairDocument14 pagesManagementof Postoperative Complicationsfollowing Endovascularaorticaneurysm Repairvictor ibarra romeroNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in Endodontics PDFDocument6 pagesPain Management in Endodontics PDFdavid bbNo ratings yet

- Play Therapy With TeenagersDocument21 pagesPlay Therapy With TeenagersRochelle HenekeNo ratings yet

- Intro To Psychology UnitsDocument38 pagesIntro To Psychology Unitsapi-325580763No ratings yet

- Coy Diet Patient BrochureDocument32 pagesCoy Diet Patient BrochureRebeca Daniela CherloabaNo ratings yet

- Gingival BleedingDocument25 pagesGingival BleedingAntony Sebastian91% (11)

- Nueva Ecija University of Science and TechnologyDocument7 pagesNueva Ecija University of Science and TechnologyKym RonquilloNo ratings yet

- PharmacologyDocument53 pagesPharmacologyapi-3743565No ratings yet

- Growth Plate InjuriesDocument10 pagesGrowth Plate InjuriesraissanindyaNo ratings yet

- 2019 HIV Drug ChartDocument5 pages2019 HIV Drug ChartETNo ratings yet