Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Financial Inclusion

Uploaded by

Ashwani RanaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Financial Inclusion

Uploaded by

Ashwani RanaCopyright:

Available Formats

COMMENTARY

Financial Inclusion

Need for Differentiation between

Access and Use

Indira Iyer

With no financial capacity to

save and invest, a dismal record

of use of bank accounts and

the severe lack of trust in the

current model of using business

correspondents, it is extremely

difficult to envisage how opening

of bank accounts will slowly

help inculcate the habit of saving

among the poor. The government

needs to rethink the measures

to make financial services more

inclusive and ask whether just

opening bank accounts is the

means to achieve it.

he Jan Dhan Yojana (JDY) was

launched on 28 August 2014 and

gauging by the 1.5 crore bank

accounts that were opened on a single

day, signalled accelerated efforts by the

government to make financial inclusion

a key goal to change lives, reduce risks,

and make a broader section of the population a part of the growth process.

Almost 7 crore accounts were opened up

to 5 November 2014 which means one

bank account being opened every 12 seconds. This is truly astounding though it

takes second place to the programme of

building a toilet every seven seconds under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. In both

these cases it is important to inquire

whether access to a bank account or to a

toilet translates into actual use of these

services, otherwise this would just turn

into a mere numbers chasing game.

of households had a bank account. Overall, in 2011 almost 60% of households

had access to credit.

However, if the purpose of opening a

bank account is to use financial services

and save and invest, then the performance is dismal. According to the World

Banks Global Financial Development

Report (2014) only 11% of those who had

a bank account had savings and only 8%

took loans. Equally alarming are the

number of bank accounts that are

opened and lie dormant. The Reserve

Bank of India (RBI) 201112 Annual

Report indicates and official data released by the government shows that almost 75% of savings accounts lie dormant (Figure 1). These figures get more

dismal if we look at the accounts opened

by business correspondents (BCs). Surveys by the Consultative Group to Assist

the Poor (CGAP) and the College of Agricultural Banking (CAB) and Microsave

(2012) indicate that an astonishing 80%

to 96% of these accounts in rural areas

lie dormant. Moreover, the 2012 CGAPCAB survey also indicated that 47% of

the BCs they attempted to contact were

untraceable. With over 3,30,000 BCs operating in rural areas covering close to

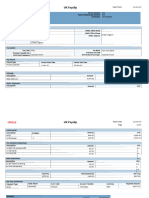

Figure 1: Dormant Bank Accounts

96

100

Financial Services

Indira Iyer (iiyer@ncaer.org) is Senior Fellow

at the National Council for Applied Economic

Research, New Delhi.

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

FEBRUARY 14, 2015

vol l no 7

Savings account

80

60

Percent

The Rangarajan Committee (2008)

broadly defines financial inclusion as

universal access to financial services by

the poor and disadvantaged people at an

affordable cost. In India, by the very

definition of financial inclusion, the

focus of the rhetoric has primarily been

on access to these services according to a

set of various indicators like the percentage of households having a bank account

or the number of bank branches per

1,00,000 of the population. On paper,

and as the data released by the department of financial services, reveals, the

country has made substantial progress

in making financial services available to

the poor and the pace is picking up fast.

Between 2001 and 2011, the number of

households with a bank account in rural

areas increased from 30% to 54% displaying a growth of 80%. While the

growth in the urban areas was more

modest at 37%, in 2011 over two-thirds

Business correspondent

75

80

All banks

46

40

20

Inter Media RBI 2011-12

2013

CGAP-CAB Microsave

2012

2012

40% of the villages, and 60,000 operating in urban areas, it is clear that reach

does not necessarily translate into use.

Targeted Groups

The purpose of financial inclusion policies is to make affordable saving, investment and insurance options available to

the poor and the vulnerable. Not surprisingly, the most underserved are

those in greatest need of financial services the bottom 40%. The National

Council of Applied Economic Research

(NCAER) National Survey of Household

19

COMMENTARY

Income and Expenditure (NSHIE) 2011

12 survey indicates that on average, less

than 30% of those in the bottom-most

quintile have a bank account, and about

50% of households falling in the second

quintile have bank accounts as against

the national average of 60%. It is also

Figure

2: PerofCent

of Households

Having

Bank

Percent

households

having bank

account

by

Account by Quintiles quintiles

100

93 94 94

90

80

76

73

75

70

60 58 60

60

51 50 51

50

are disturbingly becoming more indebted to the moneylenders. As per this report, farm households not accessing credit from formal sources as a proportion to

total farm households are more at 95.91%,

81.26% and 77.59% in the north-eastern,

eastern and central regions, respectively.

These numbers are staggering, and goes

to show that even if on average 54% of

rural household have a bank account as

per the 2011 Census, the actual purpose of

more inclusive access is not translating to

affordable credit for the poor who really

need such services.

40

33

30

Financial Capacity and Trust

28

27

20

10

0

Quintile 1

Quintile 2

Quintile 3

Quintile 4

Quintile 5

Rural

Urban

Total

Source: NCAERNSHIE Survey 201112.

seen that lack of financial access is the

highest among casual wage labourers.

The NSHIE survey indicates that casual

wage labour comprise 38% of all households at the all-India level but only about

Figure 3: Percentage of Households Who

Fully Trust Financial Services

100

78

80

72

55

60

40

15

20

3

BCs

Mobile

money

0

Private

banks

Post

office

LIC

State owned

banks

Source: Inter Media India FII Tracker Survey 2013-14.

40% of them have a bank account. Moreover a large fraction of these accounts

are only used to withdraw payments for

work done under the Mahatma Gandhi

National Rural Employment Guarantee

Act (MgNREGA). In these cases while

having a bank account does decrease

corruption and promotes transactional

efficiency, it does not mean affordable

credit from formal sources for the rural

poor who continue to rely on informal

sources of finance at high interest rates

for their credit needs.

In fact, the Sarangi Committee report

of the Task Force (2010) on Credit Related

Issues of Farmers notes that the small

and marginal farmers who own more

than 80% of the agricultural holdings

20

The next big question is to understand

who saves and invests and whether government policies are successful in making

the poor use more financial services. The

NCAERNSHIE 201112 survey shows that

over 70% of the savings in formal institutions is by non-agricultural white collar

workers. The poorer and more disadvantaged group of households in agriculture

and allied activities form just a mere 1%

of the savings in formal institutions. In

times of financial stress, the poor, whom

the JDY scheme targets, still resort to

moneylenders for their credit needs.

Trust also plays a dominant role in

financial sector participation by households. In India, the current service delivery model of using BCs and mobile

money to increase outreach faces a formidable trust barrier. The Inter Media

India FII Tracker Survey (2013) report

bleak figures just 3% of households

fully trust BCs with their financial transactions and only 1% of households trust

the use of mobile money. If you couple

lack of trust with the fact that over 47%

of the BCs are untraceable after they

open an account, it will probably

explain why 80% to 96% of accounts

opened by BCs lie dormant and defeat

the very purpose of making financial

services more accessible and affordable

for the poor.

Multidimensional Index

With no financial capacity to save and

invest, a dismal record of use of bank

accounts and the severe lack of trust in

the current rock star model of using

BCs, it is extremely difficult to envisage

how opening of bank accounts will, as

officials put it, slowly help inculcate the

habit of saving among the poor. The government needs to rethink the measures

to make financial services more inclusive

and whether just opening bank accounts

is the means to achieve it. As a start, a

more multidimensional index of financial inclusion needs to be computed to

include both financial deepening indicators which could include the number of

bank accounts per household and the

number of bank branches per 1,000 kilometres, as well as financial habit indicators such as the number of bank accounts that are actually used, both by

quintiles as well as by the category of the

chief earner in a household (whether a

casual wage labourer, a salaried employee, etc). On another level, ways to incentivise BCs and improve their profitability

will have to form part of a holistic financial inclusion strategy to improve record

of usage and retain agents. Ultimately,

both access and use will be necessary to

smooth consumption and reduce risks

for the poor. The mere chasing of numerical targets of financial access becomes meaningless unless deeper issues

that address financial capability and

trust in service delivery are tackled

simultaneously.

EPW Index

An author-title index for EPW has been prepared for the years from 1968 to 2012. The PDFs of the

Index have been uploaded, year-wise, on the EPW website. Visitors can download the Index for

all the years from the site. (The Index for a few years is yet to be prepared and will be uploaded

when ready.)

EPW would like to acknowledge the help of the staff of the library of the Indira Gandhi Institute

of Development Research, Mumbai, in preparing the index under a project supported by the

RD Tata Trust.

FEBRUARY 14, 2015

vol l no 7

EPW

Economic & Political Weekly

You might also like

- A To Z of PrivacyDocument3 pagesA To Z of PrivacyAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Hpas PyqDocument10 pagesHpas PyqAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- POLITY StarategyDocument4 pagesPOLITY StarategyAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- 2015 ALL INDIA RANK 38 NOTES - International-AgenciesDocument29 pages2015 ALL INDIA RANK 38 NOTES - International-AgenciesRaman KumarNo ratings yet

- Geography Models, Human EcologyDocument20 pagesGeography Models, Human EcologyCheryl Morris WalderNo ratings yet

- DRDO VacancyDocument1 pageDRDO VacancyAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- 97 GenrDocument53 pages97 Genrapi-248888837No ratings yet

- Social ForestryDocument6 pagesSocial ForestryAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Agri Dev in IndiaDocument4 pagesAgri Dev in IndiaAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- SBI PO 2015 - Expected PatternDocument4 pagesSBI PO 2015 - Expected PatternAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Aptitude Shortcuts in PDF Time and DistanceDocument4 pagesAptitude Shortcuts in PDF Time and DistanceAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Bear Cartel Behind P-Notes BogeyDocument2 pagesBear Cartel Behind P-Notes BogeyAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Certificate of CharacterDocument2 pagesCertificate of CharacterJayaraj BalachandranNo ratings yet

- NABARD 15 Pre-Exam AnalysisDocument4 pagesNABARD 15 Pre-Exam AnalysisAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Inflation TargetingDocument6 pagesInflation TargetingAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Panchayati Raj - Sumamry From KurukshetraDocument5 pagesPanchayati Raj - Sumamry From KurukshetraSamar SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Iran Nuclear DealDocument3 pagesIran Nuclear DealAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Bio GeographyDocument5 pagesBio GeographyAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Coal Bed MethaneDocument4 pagesCoal Bed MethaneAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- MIH - Education in IndiaDocument4 pagesMIH - Education in IndiaAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Furthering Financial Inclusion - The HinduDocument2 pagesFurthering Financial Inclusion - The HinduAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct InvestmentDocument5 pagesForeign Direct InvestmentAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- FDI RetailDocument4 pagesFDI RetailAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Panchayati Raj - ErewiseDocument5 pagesPanchayati Raj - ErewiseAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- What Is GSTDocument6 pagesWhat Is GSTAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- Sci Tech January 2015 2Document68 pagesSci Tech January 2015 2Ashwani RanaNo ratings yet

- The Hindu Review January 1Document12 pagesThe Hindu Review January 1jyothishmohan1991No ratings yet

- EPW JanuaryDocument27 pagesEPW JanuaryAnuragKumarNo ratings yet

- Pti Diary of Events 2014Document55 pagesPti Diary of Events 2014Ashwani RanaNo ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Work-Life Balance Challenges and Solutions: Overview: Mr.D.Babin Dhas, Dr.P.KarthikeyanDocument10 pagesWork-Life Balance Challenges and Solutions: Overview: Mr.D.Babin Dhas, Dr.P.KarthikeyanKaka AwaliaNo ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesReaction PaperAmor LabitaNo ratings yet

- Uk Payslip PDFDocument3 pagesUk Payslip PDFJhonel PauloNo ratings yet

- Book of Proceedings EsdParis2018 OnlineDocument535 pagesBook of Proceedings EsdParis2018 Onlineca taNo ratings yet

- Bushra Mubeen-Change Management MidtermDocument3 pagesBushra Mubeen-Change Management Midtermbushra asad khanNo ratings yet

- LL Case INCDocument19 pagesLL Case INCJireh Dela Vega AgustinNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Interviewing WorkbookDocument24 pagesBehavioral Interviewing WorkbookJ100% (1)

- Answer KeyDocument14 pagesAnswer KeyGemaiNo ratings yet

- Minor ProjectDocument60 pagesMinor ProjectVarsha MSNo ratings yet

- Worker's Service ContractDocument3 pagesWorker's Service ContractmuneneNo ratings yet

- A Company' Pay StructureDocument21 pagesA Company' Pay StructureAneeshia SasidharanNo ratings yet

- 04-17 ResumeDocument3 pages04-17 Resumeapi-353688259No ratings yet

- Circular 3 2023 - SALARY REVIEW 2023Document4 pagesCircular 3 2023 - SALARY REVIEW 2023Gamanson ElpitiyaNo ratings yet

- National Trade Account Manager in Tampa FL Resume Robert StubingDocument2 pagesNational Trade Account Manager in Tampa FL Resume Robert StubingRobertStubingNo ratings yet

- HR Professionals Functional Competency Framework-1Document2 pagesHR Professionals Functional Competency Framework-1vvvasimmmNo ratings yet

- 3 Yr Subjects Kemu HSMDocument3 pages3 Yr Subjects Kemu HSMJoshua ConleyNo ratings yet

- Shraddha Profile - 2020Document6 pagesShraddha Profile - 2020Hemali NandaniNo ratings yet

- Why Incentive Plans Cannot WorkDocument3 pagesWhy Incentive Plans Cannot WorkFaribaTabassumNo ratings yet

- Dessler HRM12e PPT 7bDocument41 pagesDessler HRM12e PPT 7bMirul AzimiNo ratings yet

- Beralde Vs LapandayDocument4 pagesBeralde Vs Lapandaymiles1280No ratings yet

- Hina Photostm: A Good Stage Manager Is Punctual and DependableDocument9 pagesHina Photostm: A Good Stage Manager Is Punctual and DependableZuhadMahmoodNo ratings yet

- Expectation Check Document v1.5 - FinalDocument1 pageExpectation Check Document v1.5 - FinalThe Bong BumbaNo ratings yet

- Soal HRDocument18 pagesSoal HRStella BenitaNo ratings yet

- LABOR LAW Lecture 1Document4 pagesLABOR LAW Lecture 1Jason LopezNo ratings yet

- Auto Comp ReportDocument167 pagesAuto Comp ReportnilekaniNo ratings yet

- Job Analysis of The Position of "SALES MANAGER" of Bajaj Capital, Patna BranchDocument6 pagesJob Analysis of The Position of "SALES MANAGER" of Bajaj Capital, Patna BranchRuchi RaiNo ratings yet

- Book Three Conditions of Employment Title I Working Conditions and Rest Periods Hours of WorkDocument3 pagesBook Three Conditions of Employment Title I Working Conditions and Rest Periods Hours of WorkPaula BitorNo ratings yet

- Sap HR ManualDocument39 pagesSap HR ManualAmbarish DasNo ratings yet

- EHS ManagerDocument3 pagesEHS Managerapi-121631565No ratings yet

- Template Sample of Minutes of MeetingDocument3 pagesTemplate Sample of Minutes of MeetingQyezriezaneya SyamelNo ratings yet