Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Art of Proportion

Uploaded by

John EvansCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Art of Proportion

Uploaded by

John EvansCopyright:

Available Formats

1.

COLLEGE of ARCHITECTURE and PLANNING

Architecture 6390: The Art of Proportion.

Spring 2003.

Assistant Professor Taisto H. Makela. trnakela@carbon.cudenver.edu.

556-2565.

Locations:

Time:

Mondays 8:30 -11:15

"proportion:

"harmony:

"order:

"geometry:

320 A

...due relation of one thing to another or between parts of a things,

agreeable effect of apt arrangement of parts."

sequence,arrangement."

Scienceof properties & relations of magnitudes in space." OED.

Introduction

What is the role of proportion in design, particularly architecture? Where do the rules come

from and how are they to be used? What is the relationship between proportion and geometry?

Are proportions universal?

This seminar explores the basic design concept of 'proportion' as it relates to the history of

design and how it can be utilized today. Through structured exercisesin scansion, design in

general will be studied in terms of the application of proportional rules. Two specific

architectural paradigms are scrutinized: the classical and the modem. Students will explore

the classical proportional systems employed in the orders through a study of the Tuscan Order

by William Chambers of 1790. Students will also explore the Greek Doric through an inkwash. The modem is represented by the Modulor by Le Corbusier. What is it and how did he

use it to help design his buildings?

Based on these exercises,students will then develop a proportional system to further develop

one of their recent studio designs.

2.

Objectives

The objectives are broad: to acquire discipline in a traditional formal design language and

related syntactical strategies; to utilize the human body and its scale in design; to explore the

notions of narrative and ritual; to understand basic structural logic and architectonics; to

address the concepts of occupation and shelter; to develop basic graphic and presentation

skills; to appreciate architecture as an essential constituent and manifestation of cultural

values.

3.

Requirements

Students are required to fulfil all requirementsas described for each project. Attendance is

mandatory. Students also will be required to produce a digital portfolio of their work.

4.

Evaluation

The final grade is based on a comparison: with the work of other students ill the course; with

students who have previously taken the course; with the instructor's expectations relative to

the stated objectives of the course based upon his/her experience and expertise; and the clarity,

craft, and completeness of the work. Individual progress is also a consideration.

)

5.

Structure

The seminar will consist of lecture and discussion with student presentations.

6.

Bibliography

-REQUIRED:

Kimberly Elam, Geometryof Design (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001).

Richard Padovan, Proportion (New York: Spon, 1999).

SUGGESTED:

Robert Adam, Classical Architecture: A ComprehensiveHandbook to the Tradition of Classical

Style (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991).

Leon Battista Alberti, The Ten Booksof Architecture (1755) (New York: Dover, 1986).

Gyorgy Doczi, The Power of Limits: Proportional Harmonies in Nature, Art, and Architecture

(Boston: Shambala, 1994).

Drury Blakeley Alexander, The Sourcesof Classicism(Austin, Texas: The Humanities Research

Center, 1978).

Hector d'Espouy, Fragmentsfrom Greekand Roman Architecture (New York: W.W. Norton &

Company, 1981).

Frank C. Brown, Frank A. Bourne, J.R. Coolidge, Study of the Orders,revised edition, (Chicago:

American Technical Society, 1948).

William Chambers, A Treatise on the Decorative Part of Civil Architecture (1791) (New York:

Benjamin Blom, 1968)

Robert Chitham, The Classical Orders of Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1985).

W.B. Dinsmoor, The Architecture of Ancient Greece(New York: 1975).

James Gibbs, Rulesfor Drawing the SeveralParts of Architecture (?)

"Evole des Beaux Arts," Architectural Record, 1901.

Leon Krier, Drawings 1967-1980(Bruxelles: Aux Archives d'Architecture Moderne, 1981).

Rober Lawlor, SacredGeometry: Philosophyand Practice (New York, Croosroad, 1982).

Henry McGoodwin, Architectural Shadesand Shadows (Washington, D.C.: AlA, 1990, 1904).

A.

John Onians, Bearersof Meaning: The Classical Orders in Antiquity, the Middle Ages and the

Renaissance(Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press,1988).

Andrea Palladio, The Four Booksof Architecture (1570) (New York: Dover, 1965).

Sebastiano Serlio, The Five Booksof Architecture (1611) (New York: Dover, 1982).

Thomas Gordon Smith, ClassicalArchitecture: Rule and Invention (Layton, Utah: Gibbs M. Smith,

1988).

Arthur Stratton, Elementsof Fonn & Design in ClassicArchitecture (London: Studio Editions, 1987,

1925).

John Summerson, The ClassicalLanguageof Architecture (Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT, 1963).

William Wirt Turner, Fundamentals of Architectural Design (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1930).

Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre, ClassicalArchitecture: The Poeticsof Order(Cambridge,

Massachusetts: MIT,1986).

Vitruvius, The Ten Booksof Architecture (New York: Dover, 1960).

Exercises in Scansion.

"I do not know what meaning classical studies could have for our time if they were not untimely

--that is to say, acting counter to our time and thereby acting on our time and, let us hope, for

the benefit of a time to come."

Nietzsche, "On the uses and disadvantages of history for life," 1874.

"It is the Acropolis that made a rebel of me. One clear image will stand in my mind forever:

the Parthenon. Stark, stripped, economical, violent; a clamorous outcry against a landscape of

grace and terror. All strength and purity."

Le Corbusier, Fourth Meeting of the CIAM, 1933.

THE TUSCAN ORDER.

The Tuscan Order is the most basic of the Classical Orders. The Tuscan order embodies a rigorous logic

of composition that reveals itself through graphical analysis. Through such an analysis, the student

will acquire an understanding of an architectural language or system that still asserts its authority.

Contemporary architectural design is essentially meaningless without an appreciation of the mythical

backdrop of the Classical Orders. Even today many architects argue that to do architecture is to do

Classical Architecture.

Phase1:

Construct a graphic analysis of the Tuscan Order in graphite on trace after that

delineated by William Chambers in his A Treatiseon the Decorative Part of Civil

Architecture (1791) (photocopy). Your analysis should explore the logic of how this

particular Tuscan Order is constructed through geome~ and proportional

relationships. Becauseof the inherent distortion produced by multiple reproduction of

the image, set a scale and then construct the Order along the x and y axes. This will

provide you with more accuratemeasurements. Read pages 3-15 from Brown, Bourne,

and Coolidge (photocopy).

Phase2:

A.

Construct a Tuscan Order (including the complete shaft of the column) based on

that of Chambers in graphite on trace utilizing the proportional relationships

revealed in Phase 1. Use a compass or dividers to construct the Order in terms of

proportional relationships. If you have a convincing argument to change some of the

proportional relationships of Chambers, you may do so. The result will beyour own

order. Construction lines will be done in ink (use no more than two line weights) to

clearly show the logic of proportions and geometry used. Use graphite for the

remainder (choose your lead weight carefully). The width of the ball of your foot

equals Chambers's 60 minutes or 2 modules. Refer to pages 99-100and plate 34 of Robert

Chitham, The Classical Orders of Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1985) for the

diminution of the column.

B .Construct

and render a Tuscan Order (including the complete shaft of the

column) using ink on velum based on your graphite exercisein part A. Enlarge the scale

so that the width of the ball of your foot equals Chambers's 30 minutes or 1 module.

Carefully choose your line weights and limit them to no more than three. Include line

shading following the example of Chambers. Your rendering must be clearly explained

by clearly-visible graphite construction lines.

B.

THE DORIC ORDER & Ink-wash.

Workshop: Ink-wash techniquesand materials

Construct the Doric Order in pencil and render it with an ink wash. Use the Doric

Order as described on page 17 in Study of the Ordersby Brown, Bourne and Coolidge

(Chicago: American Technical Society, 1948). You may choose either the Denticular or

Mutular version. Also read pages 16-28(photocopy). Refer to Henry McGoodwin,

Architectural Shadesand Shadows(Washington, D.C.: AlA, 1909, 1990).

First do a gradation exercise consisting of 11/2" squares:

(I, 2, 4, 8, 16,32 drops acrossand I, 2, 4, 8, 16washes down)

Ink-wash materials list (Meininger's or?):

Permanent illdia illk (Pelikan).

One tube "RoseMadder" water colour (Windsor Newton).

#4 or #5 and #12 watercolour bullet-shaped brushes (come to a point).

Strathmore Gemini or Lanaquarrel or Arches 140pound cold-pressed paper

(about 22" x 30").

Lineco Neutral Ph. White Adhesive ($7.50) or Sobo glue ($3.29).

24" x 32" 3/4" solid core board (treat surface with satin-finish latex sealer)

Large sponge.

Paper towels.

6 small containers.

c.

Le MODULOR by Le CORBUSIER.

Replace Le Corbusier's 6'0" module for his Modulor with your own height. Modify both red and

blue scales accordingly.

This project gives us the opportunity to further explore the relationship of the Body and the Building

as well as exercise the knowledge of proportion, scale and measure gained in Section 1. Your

proportional system should have the potential to encompass all elements of the design at all scales.

NAAB Student

Performance

Criteria.

12.9

Use of Precedents

Ability to provide a coherentrationalefor the programmaticand formal precedents

employedin the

conceptualizationand developmentof architectureandurbandesignprojects

12.16 Fonnal OrderingSystems

Understandingof the fundamentalsof visual perceptionandthe principlesandsystemsof orderthat infonn two- and

three-dimensionaldesign,architecturalcomposition,andurbandesign

@Copyright by Taisto H. Makela2002. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- The Power of Buildings, 1920-1950: A Master Draftsman's RecordFrom EverandThe Power of Buildings, 1920-1950: A Master Draftsman's RecordNo ratings yet

- The Architect, or Practical House Carpenter (1830)From EverandThe Architect, or Practical House Carpenter (1830)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Tadao AndoDocument18 pagesTadao AndoAbhimanyu SetiaNo ratings yet

- Lars SpuybroekDocument30 pagesLars SpuybroekVignesh VickyNo ratings yet

- Anamorphic Perspective & Illusory ArchitectureDocument20 pagesAnamorphic Perspective & Illusory Architectureunicum8541No ratings yet

- Le Corbusier LectureDocument110 pagesLe Corbusier LectureMurtaza NooruddinNo ratings yet

- ProportionDocument9 pagesProportionAshwiniAshokkumarNo ratings yet

- Architectural Sketching and Drawing in Perspective 1906 PDFDocument141 pagesArchitectural Sketching and Drawing in Perspective 1906 PDFNacho MartinezNo ratings yet

- AEPresentation ArchitecturalElementsDocument34 pagesAEPresentation ArchitecturalElementsDanielE.DzansiNo ratings yet

- Geometry of DesignDocument18 pagesGeometry of DesignmuDragON100% (1)

- Architecture DrawingDocument20 pagesArchitecture DrawingQalinlle CadeNo ratings yet

- Naegele D. - Le Corbusier's Seeing Things La Vision de L'objectif and L'espace Indicible PDFDocument8 pagesNaegele D. - Le Corbusier's Seeing Things La Vision de L'objectif and L'espace Indicible PDFAnthi RoziNo ratings yet

- Ornament ReadingDocument72 pagesOrnament Readingflegeton_du100% (1)

- Architectural Ebook Collection by Pal CiprianDocument286 pagesArchitectural Ebook Collection by Pal CiprianAliria ColloderNo ratings yet

- Ando Tadao Architect PDFDocument17 pagesAndo Tadao Architect PDFAna MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Frank Gehry Sketches PDFDocument22 pagesFrank Gehry Sketches PDFDumitru Vlasceanu Ionatan EliseiNo ratings yet

- 03 House-III PDFDocument10 pages03 House-III PDFAriel BarriosNo ratings yet

- Nesbitt Theorizing A New Agenda For Architecture 1996 P 516 528 Email PDFDocument9 pagesNesbitt Theorizing A New Agenda For Architecture 1996 P 516 528 Email PDFFardilla Rizqiyah0% (1)

- Zaha Hadid - Sketches - by Zellweger - (Architecture Ebook)Document62 pagesZaha Hadid - Sketches - by Zellweger - (Architecture Ebook)Budega100% (19)

- The Berlin Block as an Urban Tool for Compact City GrowthDocument49 pagesThe Berlin Block as an Urban Tool for Compact City GrowthMadalina ZagarinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 IRender NXTDocument15 pagesChapter 14 IRender NXTCarlos Granados100% (1)

- Le Corbuser and Purism PDFDocument6 pagesLe Corbuser and Purism PDFMurtaza NooruddinNo ratings yet

- Space, StewartDocument5 pagesSpace, StewartANo ratings yet

- Geometry in ArchitectureDocument23 pagesGeometry in ArchitectureMihai PopNo ratings yet

- Pelkonen What About Space 2013Document7 pagesPelkonen What About Space 2013Annie PedretNo ratings yet

- Shim Sutcliffe The 2001 Charles & Ray Eames Lecture - Michigan Architecture Papers 9Document98 pagesShim Sutcliffe The 2001 Charles & Ray Eames Lecture - Michigan Architecture Papers 9DanielE.Dzansi100% (1)

- The American Architect and Building News, Vol. 27, No. 733, January 11, 1890From EverandThe American Architect and Building News, Vol. 27, No. 733, January 11, 1890No ratings yet

- DiagramDocument4 pagesDiagramMaria BurevskiNo ratings yet

- Wittkower The Changing Concept of ProportionDocument18 pagesWittkower The Changing Concept of Proportiondadaesttout100% (1)

- Superstudio PDFDocument7 pagesSuperstudio PDFShoupin Zhang100% (1)

- The Lived Metaphor: Houses by Pezo von EllrichshausenDocument2 pagesThe Lived Metaphor: Houses by Pezo von EllrichshausenDorian VujnovićNo ratings yet

- Alvar Aalto A Life's WorkDocument10 pagesAlvar Aalto A Life's WorkSanyung LeeNo ratings yet

- Experiencing Architecture - Contrasting EffectsDocument8 pagesExperiencing Architecture - Contrasting EffectsgarimaNo ratings yet

- Wagner, Modern Architecture, 1896Document3 pagesWagner, Modern Architecture, 1896Nicholas YinNo ratings yet

- Interior of House for the Couples in Burgenland, AustriaDocument6 pagesInterior of House for the Couples in Burgenland, AustriaRoberto da MattaNo ratings yet

- The Eyes of The Skin - Opinion Piece.Document2 pagesThe Eyes of The Skin - Opinion Piece.Disha RameshNo ratings yet

- Rudolf Wittkower and Arch Principles - PAYNEDocument22 pagesRudolf Wittkower and Arch Principles - PAYNEkosti7No ratings yet

- Final Comparative StudyDocument20 pagesFinal Comparative Studyapi-399503726No ratings yet

- Ornament and (as) Structure – New Biological ParadigmDocument36 pagesOrnament and (as) Structure – New Biological ParadigmKavi Sakthi100% (1)

- Wang Shu PDFDocument14 pagesWang Shu PDFAlexandra TotoianuNo ratings yet

- Movement After ModernismDocument17 pagesMovement After ModernismAesthetic ArchNo ratings yet

- Articulate Surface: Ornament and - Technology I L J - I Contemporary ArchitectureDocument3 pagesArticulate Surface: Ornament and - Technology I L J - I Contemporary ArchitectureMilos KosticNo ratings yet

- Frank Lloyd Wright & Taliesin Architects - A Living ArchitectureDocument290 pagesFrank Lloyd Wright & Taliesin Architects - A Living ArchitectureOana MunteanuNo ratings yet

- Thebes of The Seven GatesDocument33 pagesThebes of The Seven Gatesccampo44No ratings yet

- Space and FormDocument5 pagesSpace and FormJagdip Singh100% (1)

- Citta Nouva and Broadacre CityDocument25 pagesCitta Nouva and Broadacre CityYamini AnandNo ratings yet

- Avantika Verma's Portfolio on Principles of Architectural Form and SpaceDocument25 pagesAvantika Verma's Portfolio on Principles of Architectural Form and SpaceAvantika VermaNo ratings yet

- Chaos and Order in Architectural DesignDocument11 pagesChaos and Order in Architectural DesignBitaran Jang Maden100% (1)

- Selected Topics (Perspective Drawing) Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesSelected Topics (Perspective Drawing) Chapter PDFKartikey BaghelNo ratings yet

- Frank Furness: Architecture in the Age of the Great MachinesFrom EverandFrank Furness: Architecture in the Age of the Great MachinesNo ratings yet

- Introductory Computer Methods & Numerical AnalysisDocument17 pagesIntroductory Computer Methods & Numerical AnalysisJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Room Heights in Building DesignDocument2 pagesRoom Heights in Building DesignJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- D.ds.57.03 Heavy AnglesDocument1 pageD.ds.57.03 Heavy AnglesJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- ADC Flexible Duct Performance & Installation Standards. Installation Guidelines. 4th Ed.Document8 pagesADC Flexible Duct Performance & Installation Standards. Installation Guidelines. 4th Ed.John EvansNo ratings yet

- Internal Communications Cable Color CodeDocument1 pageInternal Communications Cable Color CodeJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Ajax Fastener HandbookDocument132 pagesAjax Fastener Handbookandrew_ferrier9390No ratings yet

- FlourDocument1 pageFlourJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Anchors 1Document46 pagesAnchors 1John EvansNo ratings yet

- Building Code of Australia ComplianceDocument1 pageBuilding Code of Australia ComplianceJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- MATHCAD: Teaching and Learning Tool For Reinforced Concrete DesignDocument8 pagesMATHCAD: Teaching and Learning Tool For Reinforced Concrete DesignJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Internal Communications Cable Color CodeDocument1 pageInternal Communications Cable Color CodeJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Ductless Air Conditioning SystemsDocument24 pagesDuctless Air Conditioning SystemsJohn Evans100% (1)

- Object Oriented Programming Via Fortran 90Document23 pagesObject Oriented Programming Via Fortran 90hungdn2121No ratings yet

- Agassi, Joseph - Leibniz's Place Ind The History of Physics. J. Hist. Ideas, 30, 1969, 331-44Document15 pagesAgassi, Joseph - Leibniz's Place Ind The History of Physics. J. Hist. Ideas, 30, 1969, 331-44fotografia_No ratings yet

- Design Standards For Urban Infrastructure. 5 DRIVEWAYSDocument15 pagesDesign Standards For Urban Infrastructure. 5 DRIVEWAYSJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Adelaide Brighton Cement - DIY - PavingDocument4 pagesAdelaide Brighton Cement - DIY - PavingJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- NCCI: Design of Portal Frame Eaves Connections. ExampleDocument23 pagesNCCI: Design of Portal Frame Eaves Connections. ExampleJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- How To Build A Besser Block Swimming PoolDocument4 pagesHow To Build A Besser Block Swimming PoolDedy KristiantoNo ratings yet

- Landscape Solutions - Paving and Retaining WallDocument28 pagesLandscape Solutions - Paving and Retaining WallJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Bricklaying DIYDocument4 pagesBricklaying DIYJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- The A-Z of Ducted AC - Understanding Air-ConditioningDocument7 pagesThe A-Z of Ducted AC - Understanding Air-ConditioningJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- RenderingDocument4 pagesRenderingJohn Evans100% (1)

- How To Lay PaversDocument2 pagesHow To Lay PaversJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- 2 Building With Plasterboard - Jan 2014Document24 pages2 Building With Plasterboard - Jan 2014John Evans100% (1)

- Plywood Veneer Grades-SpecificationDocument1 pagePlywood Veneer Grades-SpecificationJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Loose Nails-Product CatalogueDocument16 pagesLoose Nails-Product CatalogueJohn EvansNo ratings yet

- Technical Manual WholeDocument93 pagesTechnical Manual WholeVincent MutambirwaNo ratings yet

- EDK TestsDocument30 pagesEDK TestsDougNewNo ratings yet

- KNAUF Technical Manual Jan2014Document393 pagesKNAUF Technical Manual Jan2014John Evans100% (2)

- Reflections of The Heian Period in Modern Day JapanDocument8 pagesReflections of The Heian Period in Modern Day JapanPamela VarugheseNo ratings yet

- Folk ArtDocument7 pagesFolk ArtCha CanceranNo ratings yet

- NIPPON THERMOPLASTIC ROADLINE MARKING PAINTDocument2 pagesNIPPON THERMOPLASTIC ROADLINE MARKING PAINTRUMM100% (1)

- Luther Music Theory Final Draft 231011 OnlineDocument26 pagesLuther Music Theory Final Draft 231011 Onlinetito154aNo ratings yet

- Julie MehretuDocument7 pagesJulie MehretuChristopher ServantNo ratings yet

- SkylamDocument50 pagesSkylamreynaldo widiantoNo ratings yet

- Test - Past Simple - To BeDocument2 pagesTest - Past Simple - To BeMadalina CristeaNo ratings yet

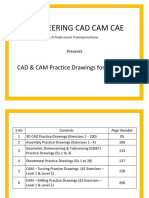

- CAD-CAM PRACTICE DRAWINGS For BEGINNERS PDFDocument232 pagesCAD-CAM PRACTICE DRAWINGS For BEGINNERS PDFelias attalah100% (2)

- Site Technology I: Grading & LandformDocument7 pagesSite Technology I: Grading & LandformBabulalSahuNo ratings yet

- Amish Quilt Patterns - 32 Pieced Patterns (Gnv64)Document108 pagesAmish Quilt Patterns - 32 Pieced Patterns (Gnv64)gnelmes100% (1)

- Beautiful Yellow Flower PowerPoint TemplatesDocument61 pagesBeautiful Yellow Flower PowerPoint TemplatesnilamNo ratings yet

- Presentation of Business LetterDocument28 pagesPresentation of Business LetterDELA CRUZ Janelle F.No ratings yet

- Shakes Bio Fill inDocument4 pagesShakes Bio Fill inSonsaku HakufuNo ratings yet

- CubismDocument4 pagesCubismCassie CutieNo ratings yet

- This Masquerade DMDocument1 pageThis Masquerade DMPieter-Jan Blomme100% (2)

- 352geo Bas Sand Specepfications PDFDocument9 pages352geo Bas Sand Specepfications PDFNurul AlamNo ratings yet

- Detailed Estimate of A G-3 Building in Excel - Part 11 - Headroom & Lift Slab PDFDocument1 pageDetailed Estimate of A G-3 Building in Excel - Part 11 - Headroom & Lift Slab PDFmintu PatelNo ratings yet

- Trade Show ColourDocument11 pagesTrade Show ColourkaoliveNo ratings yet

- English1 ResearchDocument24 pagesEnglish1 ResearchCeleste Desiree100% (1)

- Searching Music Incipits in Metric Space With Locality-Sensitive Hashing - CodeProjectDocument6 pagesSearching Music Incipits in Metric Space With Locality-Sensitive Hashing - CodeProjectGabriel GomesNo ratings yet

- Novelty ArchitectureDocument5 pagesNovelty ArchitectureSharmistha Talukder KhastagirNo ratings yet

- Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau - ArtDocument36 pagesAugusto Ferrer-Dalmau - ArtManuel NeivaNo ratings yet

- D& D5e - (Midnight Tower) - A Most Unexpected Zombie InvasionDocument13 pagesD& D5e - (Midnight Tower) - A Most Unexpected Zombie InvasionDizetSmaNo ratings yet

- Architecture in Ancient GreeceDocument13 pagesArchitecture in Ancient GreeceAbigael SantosNo ratings yet

- Rajko Petrov. Freestyle and Greco-Roman WrestlingDocument258 pagesRajko Petrov. Freestyle and Greco-Roman Wrestlingandriy11296% (24)

- Creative ImagesDocument28 pagesCreative ImagesFabio Nagual100% (2)

- Mirabehn Gandhi and BeethovenDocument2 pagesMirabehn Gandhi and BeethovenHarmony SiganporiaNo ratings yet

- John Lent Comic Books and Comic Strips in The UnDocument357 pagesJohn Lent Comic Books and Comic Strips in The UnAbhishek Kashyap100% (2)

- 25 My LunchDocument11 pages25 My Lunch周正雄100% (1)

- Spring 2013 Interweave Retail CatalogDocument122 pagesSpring 2013 Interweave Retail CatalogInterweave100% (2)