Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Medicine - IJMPS - The Experiences and Needs - Ira Suarilah

Uploaded by

TJPRC PublicationsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Medicine - IJMPS - The Experiences and Needs - Ira Suarilah

Uploaded by

TJPRC PublicationsCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Medicine and

Pharmaceutical Sciences (IJMPS)

ISSN(P): 2250-0049; ISSN(E): 2321-0095

Vol. 5, Issue 3, Jun 2015, 65-72

TJPRC Pvt. Ltd.

THE EXPERIENCES AND NEEDS OF FAMILIES OF PATIENTS WITH TRAUMATIC

BRAIN INJURY: A QUALITATIVE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

SUARILAH, IRA

Faculty of Nursing, University of Airlangga Kampus C Mulyorejo Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia

ABSTRACT

The effect of TBI has been described as one of the greatest challenges to both the injured patients and families

(Tomberg et al., 2007, Pierce and Hanks, 2006, Hart et al., 2003). Families of TBI patients have attracted the interest of

many disciplines (Allen et al., 1994, Anderson et al., 2002,Carnevale et al., 2002) to conduct research on their experiences

and needs.

Concerning the urgency of supporting a TBI patients family, the type of participants of this systematic review

protocol has been modified. Similarly, in the range of severity measurement by GCS and PTA, MS-TBI, this acronym,

MS-TBI, will then be used for short, moderate and severe TBI. This might have experienced similar problems and

persisted for an unpredictable time (Codd et al., 2011, Mills, 2009, Hawley, 2003,Hawley and Joseph, 2008). Almost

seventy per cent of MTBI patients and their families face the same difficulties as STBI patients (Dikmen et al., 2003).

Generally, this review will concern both MS-TBI patients family needs.

In spite of the fact that a well conducted systematic review (SR) generates quality evidence in clinical practice

(Lugtenberg et al., 2009, Moher et al., 2011, Squires et al., 2011), there is no such qualitative review of MS-TBI patients

families needs during and after hospitalisation to be found in the Joanna Briggs Institute libraries nor quantitative has been

retrieved in the Cohrane library. Due to the importance of exploring TBI patients families needs, to help families cope

with brain damage, a qualitative SR on that topic needs to be conducted.

KEYWORDS: Families of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury, GCS and PTA, MS-TBI

INTRODUCTION

Methodology

The search for the current review was retrieved from February until July 2012. An initial search started in the JBI,

The Campbell Collaboration and The NHS Centre for Research and Dissemination databases for qualitative systematic

reviews on families needs and TBI patients. This was followed by search in the bibliographies of major electronic

databases such as CINAHL, MEDLINE Ovid, MEDLINE Proquest, Cirrie, BNI, PsycInfo, Web of knowledge and Web of

science.

The results of the final search in each database were pooled into Endnote X5 and duplications were eliminated.

Similarly, wholly relevant papers needed to be screened systematically; the first selection excluded the title of the studies,

and the second by abstract. During this process, several abstracts might not reveal adequate information on methodology,

method and participants. Consequently, articles without abstract held in reserve, were searched for full text evaluation.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

66

Suarilah, Ira

Quality Assessment

The standardised critical appraisal tool of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for qualitative assessment and review

instrument (QARI) was used to manage, appraise, extract and synthesise qualitative data as part of a systematic review of

evidence. Criteria 1-5 in the JBI quality appraisal tool, dealt with congruence between philosophy, methodology and

analysis was applied for this SR (JBI, 2004).

Data Extraction

The data extracted includes methodology, method, phenomena of interest, setting, geographical, cultural,

participants, data analysis, authors conclusion and reviewers comments. Data extraction involves transferring data from the

original paper using an approach agreed upon and standardised for the specific review. Accordingly, analysis and synthesis

is processed by QARI software data extraction instrument 2011

Data Synthesis

All data results were classified hierarchal. The first hierarchy of evidence is unequivocal. The second credible

evidence is plausible in the light of the data and theoretical framework. The last hierarchy is unsupported.

FINDINGS

After examining 374 titles and abstracts, 59 studies appeared eligible for this review and, thus, the full articles

were retrieved. After the completed papers were received and compared to the eligibility criteria for this review, 47 studies

were excluded for the following reasons; methodology and/or method irrelevant (n=20). Acquired brain injury severity

qualification was not classified (n=10); family, patient and HPs experience on needs was not classified (n=9), family needs

were not separated based on brain injury severity level.

Table 1: Characteristics of Including Studies

Impact Factor (JCC): 5.4638

NAAS Rating: 3.54

The Experiences and Needs of Families of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Qualitative Systematic Review

67

Table 2: Characteristics of Including Studies

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

68

Suarilah, Ira

DISCUSSIONS

There are three meta-syntheses; every theme relates to the others. This inter-relation of need might well be

experienced by families through their entire lives, and it begins by TBI relatives being admitted until re-entry into the

community. As a whole, three syntheses then will be re-interpreted to capture the essence of this SR phenomenon of

interest.

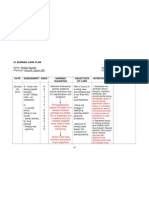

Table 3: A Meta-Synthesis Experience and Needs of TBI Patients Family

Impact Factor (JCC): 5.4638

NAAS Rating: 3.54

69

The Experiences and Needs of Families of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Qualitative Systematic Review

Information, Education, Involvement in Care, Feeling of Resourcefulness and Empowerment as Perceived by

Families

The first synthesis is that during the hospitalisation period families face dramatic change in two places; hospital

and home environment where families have insufficient information, education, involvement in care and resources of TBI.

As it has been reported in a recent study, families need to know everything about their relatives condition (Bond et al.,

2003) from the very beginning that they were admitted to hospital. Accordingly, there are several issues regarding the

earlier information as perceived by family. Bond et al (2003) have reported that during the 24-48 hours after their TBI

relative was admitted to ICU, the family experienced a lack of concentration as to what doctors said about their relatives

condition. This might result in different interpretations between family as receiver and doctor as messenger. These

variations may then result in differences of family perspectives on information needs.

According to Hergie (2011) the way is to transfer information from messenger to receiver (Hargie, 2011), from

not knowing anything then knowing something. Information can be delivered verbally or non-verbally. To successfully

deliver information, a good interpersonal communication skill seems to be one of the answers that every HP should have

(Hugman, 2009, Bach and Grant, 2011). Further, one thing that needs to be concerned by HPs is medical vocabulary.

Common words will be easier for families to understand than medical terms. Another solution is a two-way

communication. This enables family to have a better and clearer understanding.

Consistency, Continuity and Comprehensive Professional Support

In the second synthesis, families face a struggle to adapt with TBI and need consistent, continuous and

comprehensive professional support to cope with TBI and its consequences. As it has been reported by Duff (2006) TBI

causes a dramatic change in families (Duff, 2006) and has impacted on the family structure. The effect of TBI does not

only need HPs support but also other professionals as well. However, little attention has been given to the problems of

families as individuals, sub-groups, or as a family unit. From the evidence, family appraisal, family capacity or resilience

and the process of family adaptation to living with TBI seems not to have been a part of professionals work objectives.

The deficiency of long-term professional support might result from the fact that most services available (Rotondi

et al., 2007) to persons with TBI occur during acute and inpatient care. However, from all included papers, only a few

families have access to TBI professional support (Degeneffe and Olney, 2010). The availability of this service varies with

regard to funding and public health service programming for long-term support for people with TBI and their families, for

example in the USA (Leith et al., 2004) and in Australia (Liddle et al., 2011). Generally, even in developed countries, not

all professional support which is needed by TBI patients and their families, is widely available and fully funded.

In daily life after discharge, families may play a role as a caregiver while family caregiving is the unpaid work of

a family member to help another family member. To some extent, families need expert guidance as they begin to receive

the impact of injury (Duff, 2006). To support family as a caregiver, consistent, continuous and comprehensive professional

support is strongly needed. However, Crow and Pierce (2005) argued that this service should be widely available and free

because finding funding for TBI service is a huge undertaking requiring time and energy to find. This complex problem

seems a strong issue to discuss as a policy in healthcare.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

70

Suarilah, Ira

Support from Peer, Extended Family and Society

The third synthesis is that families with a TBI person who had strong support from peers, extended family and

society might have successfully re-entered their community and continued a normal life as well. This particular support has

also contributed to inter-family relationships. Close family who experienced the burden because of TBI might need to be

listened to and received emotional support from their peers and/or extended families.

The evidence suggests that support of peers and extended families helps families to fight the feeling of losing

ones foothold (Jumisko et al., 2007, Moreno-Lopez et al., 2011,Kean, 2010). Families were forced to relinquish the life

they had planned and instead had to find new ways of living with a changed person. The loss of this familiar life entailed

great suffering.

Although some families experienced social barriers to re-gain their normal lives after TBI, this might be

associated with society lacking information with regard to TBI. In this case, the sovereignty of support from extended

families and peers through their role as support resources for families, might help reduce the effect of this barrier to

families of TBI members.

Recommendation for Future Research

As previously acknowledged, the studies selected for this meta-synthesis present qualitative findings in

developing countries. This raises the question of whether the different moments of time, health service availability, the

characteristics of families needs, and the helping context or support should be given. However, it is not possible to draw

such comparisons from this meta-synthesis and such issues on the similar phenomenon. Overall, a qualitative study in a

developing country with a high level of TBI cases and a wide age range of family members as participants is highly

recommended for further consideration.

CONCLUSIONS

This SR is condensed from the best evidence; these three meta-syntheses should be taken into account when

planning, developing, or updating HE for TBI patients families during the hospitalisation period. Hence, the result of this

SR will not only benefit both of them but also there will be a transformational leadership process for families to be leaders

in the changes to their lives caused by MS-TBI.

REFERENCES

1.

ALLEN, K., LINN, R. T., GUTIERREZ, H. & WILLER, B. S. 1994. FAMILY BURDEN FOLLOWING

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY. Rehabilitation Psychology, 39, 29-48.

2.

ANDERSON, M. I., PARMENTER, T. R. & MOK, M. 2002. The relationship between neurobehavioural

problems of severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), family functioning and the psychological wellbeing of the

spouse/caregiver: path model analysis. Brain Injury, 16, 743-757.

3.

BOND, A. E., DRAEGER, C. R. L., MANDLECO, B. & DONNELLY, M. 2003. Trauma. Needs of family

members of patients with severe traumatic brain injury: implications for evidence-based practice. Critical Care

Nurse, 23, 63-72.

Impact Factor (JCC): 5.4638

NAAS Rating: 3.54

71

The Experiences and Needs of Families of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Qualitative Systematic Review

4.

CARNEVALE, G. J., ANSELMI, V., BUSICHIO, K. & MILLIS, S. R. 2002. Changes in ratings of caregiver

burden following a community-based behavior management programme for persons with traumatic brain injury.

Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 17, 83-95.

5.

CODD, G., WHITELEY, N. & HEADWAY 2011. Claiming compensation after head injury, Nottingham,

Headway.

6.

DEGENEFFE, C. E. & LEE, G. K. 2010. Quality of Life After Traumatic Brain Injury: Perspectives of Adult

Siblings. Journal of Rehabilitation, 76, 27-36.

7.

DIKMEN, S. S., MACHAMER, J. E., POWELL, J. M. & TEMKIN, N. R. 2003. Outcome 3 to 5 years after

moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 84, 1449-1457.

8.

DUFF, D. 2002. Codman Award paper. Family concerns and responses following a severe traumatic brain injury:

a grounded theory study. Axone (Dartmouth, N.S.), 24, 14-22.

9.

HAWLEY, C. A. & JOSEPH, S. 2008. Predictors of positive growth after traumatic brain injury: A longitudinal

study. Brain Injury, 22, 427-435.

10. JBI 2004. Balancing the evidence : incorporating the synthesis of qualitative data into systematic reviews, Carlton

South, Vic., Blackwell Pub. Asia.

11. JUMISKO, E., LEXELL, J. & SODERBERG, S. 2007. Living with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury The meaning of family members' experiences. Journal of Family Nursing, 13, 353-369.

12. KEAN, S. 2010. The experience of ambiguous loss in families of brain injured ICU patients. Nursing in Critical

Care, 15, 66-75.

13. LEITH, K. H., PHILLIPS, L. & SAMPLE, P. L. 2004. Exploning the service needs and experiences of persons

with TBI and their families: the South Carolina expertience. Brain Injury, 18, 1191-1208.

14. LIDDLE, J., FLEMING, J., MCKENNA, K., TURPIN, M., WHITELAW, P. & ALLEN, S. 2011. Driving and

driving cessation after traumatic brain injury: processes and key times of need. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33,

2574-2586.

15. LEITH, K. H., PHILLIPS, L. & SAMPLE, P. L. 2004. Exploning the service needs and experiences of persons

with TBI and their families: the South Carolina expertience. Brain Injury, 18, 1191-1208.

16. MILLS, M. 2009. The maintenance of headway, London, Bloomsbury.

17. MORENO-LOPEZ, A., HOLTTUM, S. & ODDY, M. 2011. A grounded theory investigation of life experience

and the role of social support for adolescent offspring after parental brain injury. Brain Injury, 25, 1221-1233.

18. TOMBERG, T., TOOMELA, A., ENNOK, M. & TIKK, A. 2007. Changes in coping strategies, social support,

optimism and health-related quality of life following traumatic brain injury: A longitudinal study. Brain Injury,

21, 479-488.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Final - HOSPITAL BILL FORMAT PDFDocument2 pagesFinal - HOSPITAL BILL FORMAT PDFH C83% (12)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Medical FitnessDocument1 pageMedical FitnessLyrically Coded0% (1)

- Simple Tenses VerbsDocument69 pagesSimple Tenses VerbsRovi Chell100% (2)

- Flame Retardant Textiles For Electric Arc Flash Hazards: A ReviewDocument18 pagesFlame Retardant Textiles For Electric Arc Flash Hazards: A ReviewTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study of Original Paithani & Duplicate Paithani: Shubha MahajanDocument8 pagesComparative Study of Original Paithani & Duplicate Paithani: Shubha MahajanTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- The Conundrum of India-China Relationship During Modi - Xi Jinping EraDocument8 pagesThe Conundrum of India-China Relationship During Modi - Xi Jinping EraTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 31 1648794068 1ijpptjun20221Document8 pages2 31 1648794068 1ijpptjun20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Development and Assessment of Appropriate Safety Playground Apparel For School Age Children in Rivers StateDocument10 pagesDevelopment and Assessment of Appropriate Safety Playground Apparel For School Age Children in Rivers StateTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Using Nanoclay To Manufacture Engineered Wood Products-A ReviewDocument14 pagesUsing Nanoclay To Manufacture Engineered Wood Products-A ReviewTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 33 1641272961 1ijsmmrdjun20221Document16 pages2 33 1641272961 1ijsmmrdjun20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Baluchari As The Cultural Icon of West Bengal: Reminding The Glorious Heritage of IndiaDocument14 pagesBaluchari As The Cultural Icon of West Bengal: Reminding The Glorious Heritage of IndiaTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 29 1645708157 2ijtftjun20222Document8 pages2 29 1645708157 2ijtftjun20222TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 4 1644229496 Ijrrdjun20221Document10 pages2 4 1644229496 Ijrrdjun20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 52 1642055366 1ijpslirjun20221Document4 pages2 52 1642055366 1ijpslirjun20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 52 1649841354 2ijpslirjun20222Document12 pages2 52 1649841354 2ijpslirjun20222TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 51 1656420123 1ijmpsdec20221Document4 pages2 51 1656420123 1ijmpsdec20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 44 1653632649 1ijprjun20221Document20 pages2 44 1653632649 1ijprjun20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Dr. Gollavilli Sirisha, Dr. M. Rajani Cartor & Dr. V. Venkata RamaiahDocument12 pagesDr. Gollavilli Sirisha, Dr. M. Rajani Cartor & Dr. V. Venkata RamaiahTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Covid-19: The Indian Healthcare Perspective: Meghna Mishra, Dr. Mamta Bansal & Mandeep NarangDocument8 pagesCovid-19: The Indian Healthcare Perspective: Meghna Mishra, Dr. Mamta Bansal & Mandeep NarangTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- An Observational Study On-Management of Anemia in CKD Using Erythropoietin AlphaDocument10 pagesAn Observational Study On-Management of Anemia in CKD Using Erythropoietin AlphaTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 51 1651909513 9ijmpsjun202209Document8 pages2 51 1651909513 9ijmpsjun202209TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 51 1647598330 5ijmpsjun202205Document10 pages2 51 1647598330 5ijmpsjun202205TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Self-Medication Prevalence and Related Factors Among Baccalaureate Nursing StudentsDocument8 pagesSelf-Medication Prevalence and Related Factors Among Baccalaureate Nursing StudentsTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Effect of Degassing Pressure Casting On Hardness, Density and Tear Strength of Silicone Rubber RTV 497 and RTV 00A With 30% Talc ReinforcementDocument8 pagesEffect of Degassing Pressure Casting On Hardness, Density and Tear Strength of Silicone Rubber RTV 497 and RTV 00A With 30% Talc ReinforcementTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Reflexology On Post-Operative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesEffectiveness of Reflexology On Post-Operative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic ReviewTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1648211383 1ijmperdapr202201Document8 pages2 67 1648211383 1ijmperdapr202201TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- A Review of "Swarna Tantram"-A Textbook On Alchemy (Lohavedha)Document8 pagesA Review of "Swarna Tantram"-A Textbook On Alchemy (Lohavedha)TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Bolted-Flange Joint Using Finite Element MethodDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Bolted-Flange Joint Using Finite Element MethodTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Numerical Analysis of Intricate Aluminium Tube Al6061T4 Thickness Variation at Different Friction Coefficient and Internal Pressures During BendingDocument18 pagesNumerical Analysis of Intricate Aluminium Tube Al6061T4 Thickness Variation at Different Friction Coefficient and Internal Pressures During BendingTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D & Osteocalcin Levels in Children With Type 1 DM in Thi - Qar Province South of Iraq 2019Document16 pagesVitamin D & Osteocalcin Levels in Children With Type 1 DM in Thi - Qar Province South of Iraq 2019TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1653022679 1ijmperdjun202201Document12 pages2 67 1653022679 1ijmperdjun202201TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1645871199 9ijmperdfeb202209Document8 pages2 67 1645871199 9ijmperdfeb202209TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1645017386 8ijmperdfeb202208Document6 pages2 67 1645017386 8ijmperdfeb202208TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy Rehabilitation Guidelines - Lumbar DisectomyDocument6 pagesPhysiotherapy Rehabilitation Guidelines - Lumbar Disectomyalina4891No ratings yet

- Care for Patients as an LPN or LVNDocument10 pagesCare for Patients as an LPN or LVNSarah Vazquez FranNo ratings yet

- Courtenay Savage DissertationDocument230 pagesCourtenay Savage DissertationcesavageNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan (NCP) For SchizophreniformDocument8 pagesNursing Care Plan (NCP) For SchizophreniformRisa Sol AriasNo ratings yet

- Antrim Handbook-2018Document223 pagesAntrim Handbook-2018Beaulah HunidzariraNo ratings yet

- Mastering Health Economics with OUM Business SchoolDocument8 pagesMastering Health Economics with OUM Business SchoolMuhammad AliminNo ratings yet

- Leadership Shadowing ActivityDocument2 pagesLeadership Shadowing Activityapi-455549333No ratings yet

- Introduction of Cancer Center in KMUHDocument36 pagesIntroduction of Cancer Center in KMUHSantoNo ratings yet

- Correction Traumatic LPDocument2 pagesCorrection Traumatic LPFitrisia 'pipit' AmelinNo ratings yet

- Fracture Supracondylar HumerusDocument12 pagesFracture Supracondylar HumeruskemsNo ratings yet

- SLE5000.Infant Ventilator PDFDocument8 pagesSLE5000.Infant Ventilator PDFRuban RajNo ratings yet

- Calculator - Westley Croup Severity Score - UpToDateDocument2 pagesCalculator - Westley Croup Severity Score - UpToDatemario chuNo ratings yet

- Electronic Medical RecordsDocument25 pagesElectronic Medical Recordslrrcenter100% (2)

- A USER-FRIENDLY EXCEL SIMULATION FOR SCHEDULING-Erika-SimDocument9 pagesA USER-FRIENDLY EXCEL SIMULATION FOR SCHEDULING-Erika-SimMauricio Alejandro Buitrago SotoNo ratings yet

- Nursing Service Management: St. Paul Hospital TuguiegaraoDocument7 pagesNursing Service Management: St. Paul Hospital TuguiegaraoDani CawaiNo ratings yet

- Elite - The Dark Wheel NovellaDocument43 pagesElite - The Dark Wheel NovellameNo ratings yet

- JOURNAL Mam HazelDocument6 pagesJOURNAL Mam HazelBryan Voltaire Santos LannuNo ratings yet

- 031616south Africa Case StudieswebDocument16 pages031616south Africa Case StudieswebanzaniNo ratings yet

- Karolinska Hospital 05 PDFDocument16 pagesKarolinska Hospital 05 PDFSaba JafriNo ratings yet

- Canalplasty Procedure for Removing Ear Canal Bone GrowthsDocument9 pagesCanalplasty Procedure for Removing Ear Canal Bone GrowthsAlbert GheorgheNo ratings yet

- Annual Report of Durdans HospitalDocument176 pagesAnnual Report of Durdans HospitaloshanNo ratings yet

- Community Assessment: ToolsDocument12 pagesCommunity Assessment: ToolsDiana SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Cleaning Manual AppendicesDocument19 pagesCleaning Manual Appendicesgopan15No ratings yet

- Synopsis For Architectural Thesis Project - Healthcare DesignDocument4 pagesSynopsis For Architectural Thesis Project - Healthcare DesignPrathamesh Mamidwar70% (10)

- NATIONAL CONSORTIUM FOR Ph.D. IN NURSING: EFFECTIVENESS OF EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE SKILL TRAININGDocument3 pagesNATIONAL CONSORTIUM FOR Ph.D. IN NURSING: EFFECTIVENESS OF EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE SKILL TRAININGRio RioNo ratings yet

- Ambu BusDocument2 pagesAmbu BusDavid HenrionNo ratings yet

- Deborah Stover RN ResumeDocument2 pagesDeborah Stover RN Resumeapi-479158a34fNo ratings yet