Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sales August 6, 2015

Uploaded by

Alyssa Clarizze MalaluanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sales August 6, 2015

Uploaded by

Alyssa Clarizze MalaluanCopyright:

Available Formats

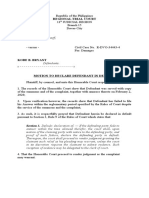

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 1

G.R. No. 112212 March 2, 1998

GREGORIO

vs.

COURT

OF

APPEALS,

BELARMINO, respondents.

FULE, petitioner,

NINEVETCH

CRUZ

and

JUAN

ROMERO, J.:

This petition for review on certiorari questions the affirmance by the Court of

Appeals of the decision 1 of the Regional Trial Court of San Pablo City, Branch 30,

dismissing the complaint that prayed for the nullification of a contract of sale of a

10-hectare property in Tanay, Rizal in consideration of the amount of P40,000.00 and

a 2.5 carat emerald-cut diamond (Civil Case No. SP-2455). The lower court's

decision disposed of the case as follows:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Court hereby renders

judgment dismissing the complaint for lack of merit and ordering

plaintiff to pay:

1. Defendant Dra. Ninevetch M. Cruz the sum of P300,000.00 as

and for moral damages and the sum of P100,000.00 as and for

exemplary damages;

2. Defendant Atty. Juan Belarmino the sum of P250,000.00 as and

for moral damages and the sum of P150,000.00 as and for

exemplary damages;

3. Defendant Dra. Cruz and Atty. Belarmino the sum of P25,000.00

each as and for attorney's fees and litigation expenses; and

4. The costs of suit.

SO ORDERED.

As found by the Court of Appeals and the lower court, the antecedent facts of this

case are as follows:

Petitioner Gregorio Fule, a banker by profession and a jeweler at the same time,

acquired a 10-hectare property in Tanay, Rizal (hereinafter "Tanay property"),

covered by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 320725 which used to be under the name

of Fr. Antonio Jacobe. The latter had mortgaged it earlier to the Rural Bank of

Alaminos (the Bank), Laguna, Inc. to secure a loan in the amount of P10,000.00, but

the mortgage was later foreclosed and the property offered for public auction upon

his default.

In July 1984, petitioner, as corporate secretary of the bank, asked Remelia Dichoso

and Oliva Mendoza to look for a buyer who might be interested in the Tanay

property. The two found one in the person of herein private respondent Dr. Ninevetch

Cruz. It so happened that at the time, petitioner had shown interest in buying a pair

of emerald-cut diamond earrings owned by Dr. Cruz which he had seen in January of

the same year when his mother examined and appraised them as genuine. Dr. Cruz,

however, declined petitioner's offer to buy the jewelry for P100,000.00. Petitioner

then made another bid to buy them for US$6,000.00 at the exchange rate of $1.00 to

P25.00. At this point, petitioner inspected said jewelry at the lobby of the Prudential

Bank branch in San Pablo City and then made a sketch thereof. Having sketched the

jewelry for twenty to thirty minutes, petitioner gave them back to Dr. Cruz who

again refused to sell them since the exchange rate of the peso at the time appreciated

to P19.00 to a dollar.

Subsequently, however, negotiations for the barter of the jewelry and the Tanay

property ensued. Dr. Cruz requested herein private respondent Atty. Juan Belarmino

to check the property who, in turn, found out that no sale or barter was feasible

because the one-year period for redemption of the said property had not yet expired

at the time.

In an effort to cut through any legal impediment, petitioner executed on October 19,

1984, a deed of redemption on behalf of Fr. Jacobe purportedly in the amount of

P15,987.78, and on even date, Fr. Jacobe sold the property to petitioner for

P75,000.00. The haste with which the two deeds were executed is shown by the fact

that the deed of sale was notarized ahead of the deed of redemption. As Dr. Cruz had

already agreed to the proposed barter, petitioner went to Prudential Bank once again

to take a look at the jewelry.

In the afternoon of October 23, 1984, petitioner met Atty. Belarmino at the latter's

residence to prepare the documents of sale. 2 Dr. Cruz herself was not around but

Atty. Belarmino was aware that she and petitioner had previously agreed to exchange

a pair of emerald-cut diamond earrings for the Tanay property. Atty. Belarmino

accordingly caused the preparation of a deed of absolute sale while petitioner and Dr.

Cruz attended to the safekeeping of the jewelry.

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 2

The following day, petitioner, together with Dichoso and Mendoza, arrived at the

residence of Atty. Belarmino to finally execute a deed of absolute sale. Petitioner

signed the deed and gave Atty. Belarmino the amount of P13,700.00 for necessary

expenses in the transfer of title over the Tanay property. Petitioner also issued a

certification to the effect that the actual consideration of the sale was P200,000.00

and not P80,000.00 as indicated in the deed of absolute sale. The disparity between

the actual contract price and the one indicated on the deed of absolute sale was

purportedly aimed at minimizing the amount of the capital gains tax that petitioner

would have to shoulder. Since the jewelry was appraised only at P160,000.00, the

parties agreed that the balance of P40,000.00 would just be paid later in cash.

As pre-arranged, petitioner left Atty. Belarmino's residence with Dichoso and

Mendoza and headed for the bank, arriving there at past 5:00 p.m. Dr. Cruz also

arrived shortly thereafter, but the cashier who kept the other key to the deposit box

had already left the bank. Dr. Cruz and Dichoso, therefore, looked for said cashier

and found him having a haircut. As soon as his haircut was finished, the cashier

returned to the bank and arrived there at 5:48 p.m., ahead of Dr. Cruz and Dichoso

who arrived at 5:55 p.m. Dr. Cruz and the cashier then opened the safety deposit box,

the former retrieving a transparent plastic or cellophane bag with the jewelry inside

and handing over the same to petitioner. The latter took the jewelry from the bag,

went near the electric light at the bank's lobby, held the jewelry against the light and

examined it for ten to fifteen minutes. After a while, Dr. Cruz asked, "Okay na ba

iyan?" Petitioner expressed his satisfaction by nodding his head.

For services rendered, petitioner paid the agents, Dichoso and Mendoza, the amount

of US$300.00 and some pieces of jewelry. He did not, however, give them half of the

pair of earrings in question which he had earlier promised.

Later, at about 8:00 o'clock in the evening of the same day, petitioner arrived at the

residence of Atty. Belarmino complaining that the jewelry given to him was fake. He

then used a tester to prove the alleged fakery. Meanwhile, at 8:30 p.m., Dichoso and

Mendoza went to the residence of Dr. Cruz to borrow her car so that, with Atty.

Belarmino, they could register the Tanay property. After Dr. Cruz had agreed to lend

her car, Dichoso called up Atty. Belarmino. The latter, however, instructed Dichoso

to proceed immediately to his residence because petitioner was there. Believing that

petitioner had finally agreed to give them half of the pair of earrings, Dichoso went

posthaste to the residence of Atty. Belarmino only to find petitioner already

demonstrating with a tester that the earrings were fake. Petitioner then accused

Dichoso and Mendoza of deceiving him which they, however, denied. They

countered that petitioner could not have been fooled because he had vast experience

regarding jewelry. Petitioner nonetheless took back the US$300.00 and jewelry he

had given them.

Thereafter, the group decided to go to the house of a certain Macario Dimayuga, a

jeweler, to have the earrings tested. Dimayuga, after taking one look at the earrings,

immediately declared them counterfeit. At around 9:30 p.m., petitioner went to one

Atty. Reynaldo Alcantara residing at Lakeside Subdivision in San Pablo City,

complaining about the fake jewelry. Upon being advised by the latter, petitioner

reported the matter to the police station where Dichoso and Mendoza likewise

executed sworn statements.

On October 26, 1984, petitioner filed a complaint before the Regional Trial Court of

San Pablo City against private respondents praying, among other things, that the

contract of sale over the Tanay property be declared null and void on the ground of

fraud and deceit.

On October 30, 1984, the lower court issued a temporary restraining order directing

the Register of Deeds of Rizal to refrain from acting on the pertinent documents

involved in the transaction. On November 20, 1984, however, the same court lifted

its previous order and denied the prayer for a writ of preliminary injunction.

After trial, the lower court rendered its decision on March 7, 1989. Confronting the

issue of whether or not the genuine pair of earrings used as consideration for the sale

was delivered by Dr. Cruz to petitioner, the lower court said:

The Court finds that the answer is definitely in the affirmative.

Indeed, Dra. Cruz delivered (the) subject jewelries (sic) into the

hands of plaintiff who even raised the same nearer to the lights of

the lobby of the bank near the door. When asked by Dra. Cruz if

everything was in order, plaintiff even nodded his satisfaction

(Hearing of Feb. 24, 1988). At that instance, plaintiff did not

protest, complain or beg for additional time to examine further the

jewelries (sic). Being a professional banker and engaged in the

jewelry business plaintiff is conversant and competent to detect a

fake diamond from the real thing. Plaintiff was accorded the

reasonable time and opportunity to ascertain and inspect the

jewelries (sic) in accordance with Article 1584 of the Civil Code.

Plaintiff took delivery of the subject jewelries (sic) before 6:00

p.m. of October 24, 1984. When he went at 8:00 p.m. that same

day to the residence of Atty. Belarmino already with a tester

complaining about some fake jewelries (sic), there was already

undue delay because of the lapse of a considerable length of time

since he got hold of subject jewelries (sic). The lapse of two (2)

hours more or less before plaintiff complained is considered by the

Court as unreasonable delay.3

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 3

The lower court further ruled that all the elements of a valid contract under Article

1458 of the Civil Code were present, namely: (a) consent or meeting of the minds;

(b) determinate subject matter, and (c) price certain in money or its equivalent. The

same elements, according to the lower court, were present despite the fact that the

agreement between petitioner and Dr. Cruz was principally a barter contract. The

lower court explained thus:

. . . . Plaintiff's ownership over the Tanay property passed unto Dra.

Cruz upon the constructive delivery thereof by virtue of the Deed

of Absolute Sale (Exh. D). On the other hand, the ownership of

Dra. Cruz over the subject jewelries (sic) transferred to the plaintiff

upon her actual personal delivery to him at the lobby of the

Prudential Bank. It is expressly provided by law that the thing sold

shall be understood as delivered, when it is placed in the control

and possession of the vendee (Art. 1497, Civil Code; Kuenzle &

Straff vs. Watson & Co. 13 Phil. 26). The ownership and/or title

over the jewelries (sic) was transmitted immediately before 6:00

p.m. of October 24, 1984. Plaintiff signified his approval by

nodding his head. Delivery or tradition, is one of the modes of

acquiring ownership (Art. 712, Civil Code).

Similarly, when Exhibit D was executed, it was equivalent to the

delivery of the Tanay property in favor of Dra. Cruz. The execution

of the public instrument (Exh. D) operates as a formal or symbolic

delivery of the Tanay property and authorizes the buyer, Dra. Cruz

to use the document as proof of ownership (Florendo v. Foz, 20

Phil. 399). More so, since Exhibit D does not contain any proviso

or stipulation to the effect that title to the property is reserved with

the vendor until full payment of the purchase price, nor is there a

stipulation giving the vendor the right to unilaterally rescind the

contract the moment the vendee fails to pay within a fixed period

(Taguba v. Vda. De Leon, 132 SCRA 722; Luzon Brokerage Co.

Inc. vs. Maritime Building Co. Inc. 86 SCRA 305; Froilan v. Pan

Oriental Shipping Co. et al. 12 SCRA 276). 4

Aside from concluding that the contract of barter or sale had in fact been

consummated when petitioner and Dr. Cruz parted ways at the bank, the trial court

likewise dwelt on the unexplained delay with which petitioner complained about the

alleged fakery. Thus:

. . . . Verily, plaintiff is already estopped to come back after the

lapse of considerable length of time to claim that what he got was

fake. He is a Business Management graduate of La Salle

University, Class 1978-79, a professional banker as well as a

jeweler in his own right. Two hours is more than enough time to

make a switch of a Russian diamond with the real diamond. It must

be remembered that in July 1984 plaintiff made a sketch of the

subject jewelries (sic) at the Prudential Bank. Plaintiff had a tester

at 8:00 p.m. at the residence of Atty. Belarmino. Why then did he

not bring it out when he was examining the subject jewelries (sic)

at about 6:00 p.m. in the bank's lobby? Obviously, he had no need

for it after being satisfied of the genuineness of the subject

jewelries (sic). When Dra. Cruz and plaintiff left the bank both of

them had fully performed their respective prestations. Once a

contract is shown to have been consummated or fully performed by

the parties thereto, its existence and binding effect can no longer be

disputed. It is irrelevant and immaterial to dispute the due

execution of a contract if both of them have in fact performed their

obligations thereunder and their respective signatures and those of

their witnesses appear upon the face of the document (Weldon

Construction v. CA G.R. No. L-35721, Oct. 12, 1987).5

Finally, in awarding damages to the defendants, the lower court remarked:

The Court finds that plaintiff acted in wanton bad faith. Exhibit 2Belarmino purports to show that the Tanay property is worth

P25,000.00. However, also on that same day it was executed, the

property's worth was magnified at P75,000.00 (Exh. 3-Belarmino).

How could in less than a day (Oct. 19, 1984) the value would (sic)

triple under normal circumstances? Plaintiff, with the assistance of

his agents, was able to exchange the Tanay property which his

bank valued only at P25,000.00 in exchange for a genuine pair of

emerald cut diamond worth P200,000.00 belonging to Dra. Cruz.

He also retrieved the US$300.00 and jewelries (sic) from his

agents. But he was not satisfied in being able to get subject

jewelries for a song. He had to file a malicious and unfounded case

against Dra. Cruz and Atty. Belarmino who are well known,

respected and held in high esteem in San Pablo City where

everybody practically knows everybody. Plaintiff came to Court

with unclean hands dragging the defendants and soiling their clean

and good name in the process. Both of them are near the twilight of

their lives after maintaining and nurturing their good reputation in

the community only to be stunned with a court case. Since the

filing of this case on October 26, 1984 up to the present they were

living under a pall of doubt. Surely, this affected not only their

earning capacity in their practice of their respective professions,

but also they suffered besmirched reputations. Dra. Cruz runs her

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 4

own hospital and defendant Belarmino is a well respected legal

practitioner. The length of time this case dragged on during which

period their reputation were (sic) tarnished and their names

maligned by the pendency of the case, the Court is of the belief

that some of the damages they prayed for in their answers to the

complaint are reasonably proportionate to the sufferings they

underwent (Art. 2219, New Civil Code). Moreover, because of the

falsity, malice and baseless nature of the complaint defendants

were compelled to litigate. Hence, the award of attorney's fees is

warranted under the circumstances (Art. 2208, New Civil Code).6

From the trial court's adverse decision, petitioner elevated the matter to the Court of

Appeals. On October 20, 1992, the Court of Appeals, however, rendered a

decision 7 affirming in toto the lower court's decision. His motion for reconsideration

having been denied on October 19, 1993, petitioner now files the instant petition

alleging that:

I. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN DISMISSING PLAINTIFF'S

COMPLAINT AND IN HOLDING THAT THE PLAINTIFF

ACTUALLY RECEIVED A GENUINE PAIR OF EMERALD

CUT DIAMOND EARRING(S) FROM DEFENDANT

CRUZ . . . ;

II. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN AWARDING MORAL AND

EXEMPLARY DAMAGES AND ATTORNEY'S FEES IN

FAVOR OF DEFENDANTS AND AGAINST THE PLAINTIFF

IN THIS CASE; and

III. THE TRIAL, COURT ERRED IN NOT DECLARING THE

DEED OF SALE OF THE TANAY PROPERTY (EXH. "D") AS

NULL AND VOID OR IN NOT ANNULLING THE SAME, AND

IN FAILING TO GRANT REASONABLE DAMAGES IN

FAVOR OF THE PLAINTIFF.8

As to the first allegation, the Court observes that petitioner is essentially raising a

factual issue as it invites us to examine and weigh anew the facts regarding the

genuineness of the earrings bartered in exchange for the Tanay property. This, of

course, we cannot do without unduly transcending the limits of our review power in

petitions of this nature which are confined merely to pure questions of law. We

accord, as a general rule, conclusiveness to a lower court's findings of fact unless it is

shown, inter alia, that: (1) the conclusion is a finding grounded on speculations,

surmises or conjectures; (2) the inference is manifestly mistaken, absurd and

impossible; (3) when there is a grave abuse of discretion; (4) when the judgment is

based on a misapprehension of facts; (5) when the findings of fact are conflicting;

and (6) when the Court of Appeals, in making its findings, went beyond the issues of

the case and the same is contrary to the admission of both parties. 9 We find nothing,

however, that warrants the application of any of these exceptions.

Consequently, this Court upholds the appellate court's findings of fact especially

because these concur with those of the trial court which, upon a thorough scrutiny of

the records, are firmly grounded on evidence presented at the trial. 10 To reiterate, this

Court's jurisdiction is only limited to reviewing errors of law in the absence of any

showing that the findings complained of are totally devoid of support in the record or

that they are glaringly erroneous as to constitute serious abuse of discretion. 11

Nonetheless, this Court has to closely delve into petitioner's allegation that the lower

court's decision of March 7, 1989 is a "ready-made" one because it was handed down

a day after the last date of the trial of the case. 12Petitioner, in this regard, finds it

incredible that Judge J. Ausberto Jaramillo was able to write a 12-page single-spaced

decision, type it and release it on March 7, 1989, less than a day after the last hearing

on March 6, 1989. He stressed that Judge Jaramillo replaced Judge Salvador de

Guzman and heard only his rebuttal testimony.

This allegation is obviously no more than a desperate effort on the part of petitioner

to disparage the lower court's findings of fact in order to convince this Court to

review the same. It is noteworthy that Atty. Belarmino clarified that Judge Jaramillo

had issued the first order in the case as early as March 9, 1987 or two years before

the rendition of the decision. In fact, Atty. Belarmino terminated presentation of

evidence on October 13, 1987, while Dr. Cruz finished hers on February 4, 1989, or

more than a month prior to the rendition of the judgment. The March 6, 1989 hearing

was conducted solely for the presentation of petitioner's rebuttal testimony. 13 In

other words, Judge Jaramillo had ample time to study the case and write the decision

because the rebuttal evidence would only serve to confirm or verify the facts already

presented by the parties.

The Court finds nothing anomalous in the said situation. No proof has been adduced

that Judge Jaramillo was motivated by a malicious or sinister intent in disposing of

the case with dispatch. Neither is there proof that someone else wrote the decision

for him. The immediate rendition of the decision was no more than Judge Jaramillo's

compliance with his duty as a judge to "dispose of the court's business promptly and

decide cases within the required periods." 14 The two-year period within which Judge

Jaramillo handled the case provided him with all the time to study it and even write

down its facts as soon as these were presented to court. In fact, this Court does not

see anything wrong in the practice of writing a decision days before the scheduled

promulgation of judgment and leaving the dispositive portion for typing at a time

close to the date of promulgation, provided that no malice or any wrongful conduct

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 5

attends its adoption. 15 The practice serves the dual purposes of safeguarding the

confidentiality of draft decisions and rendering decisions with promptness. Neither

can Judge Jaramillo be made administratively answerable for the immediate

rendition of the decision. The acts of a judge which pertain to his judicial functions

are not subject to disciplinary power unless they are committed with fraud,

dishonesty, corruption or bad faith. 16 Hence, in the absence of sufficient proof to the

contrary, Judge Jaramillo is presumed to have performed his job in accordance with

law and should instead be commended for his close attention to duty.

Having disposed of petitioner's first contention, we now come to the core issue of

this petition which is whether the Court of Appeals erred in upholding the validity of

the contract of barter or sale under the circumstances of this case.

The Civil Code provides that contracts are perfected by mere consent. From this

moment, the parties are bound not only to the fulfillment of what has been expressly

stipulated but also to all the consequences which, according to their nature, may be

in keeping with good faith, usage and law. 17 A contract of sale is perfected at the

moment there is a meeting of the minds upon the thing which is the object of the

contract and upon the price. 18 Being consensual, a contract of sale has the force of

law between the contracting parties and they are expected to abide in good faith by

their respective contractual commitments. Article 1358 of the Civil Code which

requires the embodiment of certain contracts in a public instrument, is only for

convenience, 19 and registration of the instrument only adversely affects third

parties. 20 Formal requirements are, therefore, for the benefit of third parties. Noncompliance therewith does not adversely affect the validity of the contract nor the

contractual rights and obligations of the parties thereunder.

It is evident from the facts of the case that there was a meeting of the minds between

petitioner and Dr. Cruz. As such, they are bound by the contract unless there are

reasons or circumstances that warrant its nullification. Hence, the problem that

should be addressed in this case is whether or not under the facts duly established

herein, the contract can be voided in accordance with law so as to compel the parties

to restore to each other the things that have been the subject of the contract with their

fruits, and the price with interest.21

Contracts that are voidable or annullable, even though there may have been no

damage to the contracting parties are: (1) those where one of the parties is incapable

of giving consent to a contract; and (2) those where the consent is vitiated by

mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud. 22 Accordingly, petitioner

now stresses before this Court that he entered into the contract in the belief that the

pair of emerald-cut diamond earrings was genuine. On the pretext that those pieces

of jewelry turned out to be counterfeit, however, petitioner subsequently sought the

nullification of said contract on the ground that it was, in fact, "tainted with

fraud" 23 such that his consent was vitiated.

There is fraud when, through the insidious words or machinations of one of the

contracting parties, the other is induced to enter into a contract which, without them,

he would not have agreed to. 24 The records, however, are bare of any evidence

manifesting that private respondents employed such insidious words or machinations

to entice petitioner into entering the contract of barter. Neither is there any evidence

showing that Dr. Cruz induced petitioner to sell his Tanay property or that she

cajoled him to take the earrings in exchange for said property. On the contrary, Dr.

Cruz did not initially accede to petitioner's proposal to buy the said jewelry. Rather, it

appears that it was petitioner, through his agents, who led Dr. Cruz to believe that the

Tanay property was worth exchanging for her jewelry as he represented that its value

was P400,000.00 or more than double that of the jewelry which was valued only at

P160,000.00. If indeed petitioner's property was truly worth that much, it was

certainly contrary to the nature of a businessman-banker like him to have parted with

his real estate for half its price. In short, it was in fact petitioner who resorted to

machinations to convince Dr. Cruz to exchange her jewelry for the Tanay property.

Moreover, petitioner did not clearly allege mistake as a ground for nullification of

the contract of sale. Even assuming that he did, petitioner cannot successfully invoke

the same. To invalidate a contract, mistake must "refer to the substance of the thing

that is the object of the contract, or to those conditions which have principally moved

one or both parties to enter into the contract." 25 An example of mistake as to the

object of the contract is the substitution of a specific thing contemplated by the

parties with another. 26 In his allegations in the complaint, petitioner insinuated that

an inferior one or one that had only Russian diamonds was substituted for the

jewelry he wanted to exchange with his 10-hectare land. He, however, failed to prove

the fact that prior to the delivery of the jewelry to him, private respondents

endeavored to make such substitution.

Likewise, the facts as proven do not support the allegation that petitioner himself

could be excused for the "mistake." On account of his work as a banker-jeweler, it

can be rightfully assumed that he was an expert on matters regarding gems. He had

the intellectual capacity and the business acumen as a banker to take precautionary

measures to avert such a mistake, considering the value of both the jewelry and his

land. The fact that he had seen the jewelry before October 24, 1984 should not have

precluded him from having its genuineness tested in the presence of Dr. Cruz. Had

he done so, he could have avoided the present situation that he himself brought

about. Indeed, the finger of suspicion of switching the genuine jewelry for a fake

inevitably points to him. Such a mistake caused by manifest negligence cannot

invalidate a juridical act. 27 As the Civil Code provides, "(t)here is no mistake if the

party alleging it knew the doubt, contingency or risk affecting the object of the

contract."28

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 6

Furthermore, petitioner was afforded the reasonable opportunity required in Article

1584 of the Civil Code within which to examine the jewelry as he in fact accepted

them when asked by Dr. Cruz if he was satisfied with the same. 29 By taking the

jewelry outside the bank, petitioner executed an act which was more consistent with

his exercise of ownership over it. This gains credence when it is borne in mind that

he himself had earlier delivered the Tanay property to Dr. Cruz by affixing his

signature to the contract of sale. That after two hours he later claimed that the

jewelry was not the one he intended in exchange for his Tanay property, could not

sever the juridical tie that now bound him and Dr. Cruz. The nature and value of the

thing he had taken preclude its return after that supervening period within which

anything could have happened, not excluding the alteration of the jewelry or its

being switched with an inferior kind.

Both the trial and appellate courts, therefore, correctly ruled that there were no legal

bases for the nullification of the contract of sale. Ownership over the parcel of land

and the pair of emerald-cut diamond earrings had been transferred to Dr. Cruz and

petitioner, respectively, upon the actual and constructive delivery thereof. 30 Said

contract of sale being absolute in nature, title passed to the vendee upon delivery of

the thing sold since there was no stipulation in the contract that title to the property

sold has been reserved in the seller until full payment of the price or that the vendor

has the right to unilaterally resolve the contract the moment the buyer fails to pay

within a fixed period. 31 Such stipulations are not manifest in the contract of sale.

While it is true that the amount of P40,000.00 forming part of the consideration was

still payable to petitioner, its nonpayment by Dr. Cruz is not a sufficient cause to

invalidate the contract or bar the transfer of ownership and possession of the things

exchanged considering the fact that their contract is silent as to when it becomes due

and demandable. 32

Neither may such failure to pay the balance of the purchase price result in the

payment of interest thereon. Article 1589 of the Civil Code prescribes the payment of

interest by the vendee "for the period between the delivery of the thing and the

payment of the price" in the following cases:

(1) Should it have been so stipulated;

(2) Should the thing sold and delivered produce fruits or income;

(3) Should he be in default, from the time of judicial or

extrajudicial demand for the payment of the price.

Not one of these cases obtains here. This case should, of course, be

distinguished from De la Cruz v.Legaspi, 33 where the court held that failure

to pay the consideration after the notarization of the contract as previously

promised resulted in the vendee's liability for payment of interest. In the

case at bar, there is no stipulation for the payment of interest in the contract

of sale nor proof that the Tanay property produced fruits or income. Neither

did petitioner demand payment of the price as in fact he filed an action to

nullify the contract of sale.

All told, petitioner appears to have elevated this case to this Court for the principal

reason of mitigating the amount of damages awarded to both private respondents

which petitioner considers as "exorbitant." He contends that private respondents do

not deserve at all the award of damages. In fact, he pleads for the total deletion of the

award as regards private respondent Belarmino whom he considers a mere "nominal

party" because "no specific claim for damages against him" was alleged in the

complaint. When he filed the case, all that petitioner wanted was that Atty.

Belarmino should return to him the owner's duplicate copy of TCT No. 320725, the

deed of sale executed by Fr. Antonio Jacobe, the deed of redemption and the check

alloted for expenses. Petitioner alleges further that Atty. Belarmino should not have

delivered all those documents to Dr. Cruz because as the "lawyer for both the seller

and the buyer in the sale contract, he should have protected the rights of both

parties." Moreover, petitioner asserts that there was no firm basis for damages except

for Atty. Belarmino's uncorroborated testimony.34

Moral and exemplary damages may be awarded without proof of pecuniary loss. In

awarding such damages, the court shall take into account the circumstances

obtaining in the case said assess damages according to its discretion. 35 To warrant the

award of damages, it must be shown that the person to whom these are awarded has

sustained injury. He must likewise establish sufficient data upon which the court can

properly base its estimate of the amount of damages. 36 Statements of facts should

establish such data rather than mere conclusions or opinions of witnesses. 37 Thus:

. . . . For moral damages to be awarded, it is essential that the

claimant must have satisfactorily proved during the trial the

existence of the factual basis of the damages and its causal

connection with the adverse party's acts. If the court has no proof

or evidence upon which the claim for moral damages could be

based, such indemnity could not be outrightly awarded. The same

holds true with respect to the award of exemplary damages where

it must be shown that the party acted in a wanton, oppressive or

malevolent manner. 38

In this regard, the lower court appeared to have awarded damages on a ground

analogous to malicious prosecution under Article 2219 (8) of the Civil Code 39 as

shown by (1) petitioner's "wanton bad faith" in bloating the value of the Tanay

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 7

property which he exchanged for "a genuine pair of emerald-cut diamond worth

P200,00.00;" and (2) his filing of a "malicious and unfounded case" against private

respondents who were "well known, respected and held in high esteem in San Pablo

City where everybody practically knows everybody" and whose good names in the

"twilight of their lives" were soiled by petitioner's coming to court with "unclean

hands," thereby affecting their earning capacity in the exercise of their respective

professions and besmirching their reputation.

For its part, the Court of Appeals affirmed the award of damages to private

respondents for these reasons:

The malice with which Fule filed this case is apparent. Having

taken possession of the genuine jewelry of Dra. Cruz, Fule now

wishes to return a fake jewelry to Dra. Cruz and, more than that,

get back the real property, which his bank owns. Fule has obtained

a genuine jewelry which he could sell anytime, anywhere and to

anybody, without the same being traced to the original owner for

practically nothing. This is plain and simple, unjust enrichment.40

While, as a rule, moral damages cannot be recovered from a person who has filed a

complaint against another in good faith because it is not sound policy to place a

penalty on the right to litigate, 41 the same, however, cannot apply in the case at bar.

The factual findings of the courts a quo to the effect that petitioner filed this case

because he was the victim of fraud; that he could not have been such a victim

because he should have examined the jewelry in question before accepting delivery

thereof, considering his exposure to the banking and jewelry businesses; and that he

filed the action for the nullification of the contract of sale with unclean hands, all

deserve full faith and credit to support the conclusion that petitioner was motivated

more by ill will than a sincere attempt to protect his rights in commencing suit

against respondents.

As pointed out earlier, a closer scrutiny of the chain of events immediately prior to

and on October 24, 1984 itself would amply demonstrate that petitioner was not

simply negligent in failing to exercise due diligence to assure himself that what he

was taking in exchange for his property were genuine diamonds. He had rather

placed himself in a situation from which it preponderantly appears that his seeming

ignorance was actually just a ruse. Indeed, he had unnecessarily dragged respondents

to face the travails of litigation in speculating at the possible favorable outcome of

his complaint when he should have realized that his supposed predicament was his

own making. We, therefore, see here no semblance of an honest and sincere belief on

his part that he was swindled by respondents which would entitle him to redress in

court. It must be noted that before petitioner was able to convince Dr. Cruz to

exchange her jewelry for the Tanay property, petitioner took pains to thoroughly

examine said jewelry, even going to the extent of sketching their appearance. Why at

the precise moment when he was about to take physical possession thereof he failed

to exert extra efforts to check their genuineness despite the large consideration

involved has never been explained at all by petitioner. His acts thus failed to accord

with what an ordinary prudent man would have done in the same situation. Being an

experienced banker and a businessman himself who deliberately skirted a legal

impediment in the sale of the Tanay property and to minimize the capital gains tax

for its exchange, it was actually gross recklessness for him to have merely conducted

a cursory examination of the jewelry when every opportunity for doing so was not

denied him. Apparently, he carried on his person a tester which he later used to prove

the alleged fakery but which he did not use at the time when it was most needed.

Furthermore, it took him two more hours of unexplained delay before he complained

that the jewelry he received were counterfeit. Hence, we stated earlier that anything

could have happened during all the time that petitioner was in complete possession

and control of the jewelry, including the possibility of substituting them with fake

ones, against which respondents would have a great deal of difficulty defending

themselves. The truth is that petitioner even failed to successfully prove during trial

that the jewelry he received from Dr. Cruz were not genuine. Add to that the fact that

he had been shrewd enough to bloat the Tanay property's price only a few days after

he purchased it at a much lower value. Thus, it is our considered view that if this

slew of circumstances were connected, like pieces of fabric sewn into a quilt, they

would sufficiently demonstrate that his acts were not merely negligent but rather

studied and deliberate.

We do not have here, therefore, a situation where petitioner's complaint was simply

found later to be based on an erroneous ground which, under settled jurisprudence,

would not have been a reason for awarding moral and exemplary

damages. 42 Instead, the cause of action of the instant case appears to have been

contrived by petitioner himself. In other words, he was placed in a situation where he

could not honestly evaluate whether his cause of action has a semblance of merit,

such that it would require the expertise of the courts to put it to a test. His insistent

pursuit of such case then coupled with circumstances showing that he himself was

guilty in bringing about the supposed wrongdoing on which he anchored his cause of

action would render him answerable for all damages the defendant may suffer

because of it. This is precisely what took place in the petition at bar and we find no

cogent reason to disturb the findings of the courts below that respondents in this case

suffered considerable damages due to petitioner's unwarranted action.

WHEREFORE, the decision of the Court of Appeals dated October 20, 1992 is

hereby AFFIRMED in toto. Dr. Cruz, however, is ordered to pay petitioner the

balance of the purchase price of P40,000.00 within ten (10) days from the finality of

this decision. Costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 8

G.R. No. 78903 February 28, 1990

SPS. SEGUNDO DALION AND EPIFANIA SABESAJE-DALION, petitioners,

vs.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS AND RUPERTO SABESAJE,

JR., respondents.

plaintiff of the said property subject of this case, otherwise, should

defendants for any reason fail to do so, the deed shall be executed

in their behalf by the Provincial Sheriff or his Deputy;

(b) Ordering the defendants to pay plaintiff the amount of

P2,000.00 as attorney's fees and P 500.00 as litigation expenses,

and to pay the costs; and

Francisco A. Puray, Sr. for petitioners.

(c) Dismissing the counter-claim. (p. 38, Rollo)

Gabriel N. Duazo for private respondent.

The facts of the case are as follows:

MEDIALDEA, J.:

This is a petition to annul and set aside the decision of the Court of Appeals rendered

on May 26, 1987, upholding the validity of the sale of a parcel of land by petitioner

Segundo Dalion (hereafter, "Dalion") in favor of private respondent Ruperto

Sabesaje, Jr. (hereafter, "Sabesaje"), described thus:

A parcel of land located at Panyawan, Sogod, Southern Leyte,

declared in the name of Segundo Dalion, under Tax Declaration

No. 11148, with an area of 8947 hectares, assessed at P 180.00, and

bounded on the North, by Sergio Destriza and Titon Veloso, East,

by Feliciano Destriza, by Barbara Bonesa (sic); and West, by

Catalino Espina. (pp. 36-37, Rollo)

The decision affirms in toto the ruling of the trial court 1 issued on January 17, 1984,

the dispositive portion of which provides as follows:

WHEREFORE, IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING, the Court

hereby renders judgment.

(a) Ordering the defendants to deliver to the plaintiff the parcel of

land subject of this case, declared in the name of Segundo Dalion

previously under Tax Declaration No. 11148 and lately under Tax

Declaration No. 2297 (1974) and to execute the corresponding

formal deed of conveyance in a public document in favor of the

On May 28, 1973, Sabesaje sued to recover ownership of a parcel of land, based on a

private document of absolute sale, dated July 1, 1965 (Exhibit "A"), allegedly

executed by Dalion, who, however denied the fact of sale, contending that the

document sued upon is fictitious, his signature thereon, a forgery, and that subject

land is conjugal property, which he and his wife acquired in 1960 from Saturnina

Sabesaje as evidenced by the "Escritura de Venta Absoluta" (Exhibit "B"). The

spouses denied claims of Sabesaje that after executing a deed of sale over the parcel

of land, they had pleaded with Sabesaje, their relative, to be allowed to administer

the land because Dalion did not have any means of livelihood. They admitted,

however, administering since 1958, five (5) parcels of land in Sogod, Southern

Leyte, which belonged to Leonardo Sabesaje, grandfather of Sabesaje, who died in

1956. They never received their agreed 10% and 15% commission on the sales of

copra and abaca, respectively. Sabesaje's suit, they countered, was intended merely to

harass, preempt and forestall Dalion's threat to sue for these unpaid commissions.

From the adverse decision of the trial court, Dalion appealed, assigning errors some

of which, however, were disregarded by the appellate court, not having been raised

in the court below. While the Court of Appeals duly recognizes Our authority to

review matters even if not assigned as errors in the appeal, We are not inclined to do

so since a review of the case at bar reveals that the lower court has judicially decided

the case on its merits.

As to the controversy regarding the identity of the land, We have no reason to dispute

the Court of Appeals' findings as follows:

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 9

To be sure, the parcel of land described in Exhibit "A" is the same

property deeded out in Exhibit "B". The boundaries delineating it

from adjacent lots are identical. Both documents detail out the

following boundaries, to wit:

On the North-property of Sergio Destriza and Titon Veloso;

seen writing purporting to be his upon which the witness has acted

or been charged, and has thus acquired knowledge of the

handwriting of such person. Evidence respecting the handwriting

may also be given by a comparison, made by the witness or the

court, with writings admitted or treated as genuine by the party

against whom the evidence is offered, or proved to be genuine to

the satisfaction of the judge. (Rule 132, Revised Rules of Court)

On the East-property of Feliciano Destriza;

And on the basis of the findings of fact of the trial court as follows:

On the South-property of Barbara Boniza and

On the West-Catalino Espina.

(pp. 41-42, Rollo)

The issues in this case may thus be limited to: a) the validity of the contract of sale of

a parcel of land and b) the necessity of a public document for transfer of ownership

thereto.

The appellate court upheld the validity of the sale on the basis of Secs. 21 and 23 of

Rule 132 of the Revised Rules of Court.

SEC. 21. Private writing, its execution and authenticity, how

proved.-Before any private writing may be received in evidence, its

due execution and authenticity must be proved either:

(a) By anyone who saw the writing executed;

(b) By evidence of the genuineness of the handwriting of the

maker; or

(c) By a subscribing witness

xxx xxx xxx

SEC. 23. Handwriting, how proved. The handwriting of a

person may be proved by any witness who believes it to be the

handwriting of such person, and has seen the person write, or has

Here, people who witnessed the execution of subject deed

positively testified on the authenticity thereof. They categorically

stated that it had been executed and signed by the signatories

thereto. In fact, one of such witnesses, Gerardo M. Ogsoc, declared

on the witness stand that he was the one who prepared said deed of

sale and had copied parts thereof from the "Escritura De Venta

Absoluta" (Exhibit B) by which one Saturnina Sabesaje sold the

same parcel of land to appellant Segundo Dalion. Ogsoc copied the

bounderies thereof and the name of appellant Segundo Dalion's

wife, erroneously written as "Esmenia" in Exhibit "A" and

"Esmenia" in Exhibit "B". (p. 41, Rollo)

xxx xxx xxx

Against defendant's mere denial that he signed the document, the

positive testimonies of the instrumental Witnesses Ogsoc and

Espina, aside from the testimony of the plaintiff, must prevail.

Defendant has affirmatively alleged forgery, but he never presented

any witness or evidence to prove his claim of forgery. Each party

must prove his own affirmative allegations (Section 1, Rule 131,

Rules of Court). Furthermore, it is presumed that a person is

innocent of a crime or wrong (Section 5 (a), Idem), and defense

should have come forward with clear and convincing evidence to

show that plaintiff committed forgery or caused said forgery to be

committed, to overcome the presumption of innocence. Mere

denial of having signed, does not suffice to show forgery.

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 10

In addition, a comparison of the questioned signatories or

specimens (Exhs. A-2 and A-3) with the admitted signatures or

specimens (Exhs. X and Y or 3-C) convinces the court that Exhs.

A-2 or Z and A-3 were written by defendant Segundo Dalion who

admitted that Exhs. X and Y or 3-C are his signatures. The

questioned signatures and the specimens are very similar to each

other and appear to be written by one person.

Further comparison of the questioned signatures and the specimens

with the signatures Segundo D. Dalion appeared at the back of the

summons (p. 9, Record); on the return card (p. 25, Ibid.); back of

the Court Orders dated December 17, 1973 and July 30, 1974 and

for October 7, 1974 (p. 54 & p. 56, respectively, Ibid.), and on the

open court notice of April 13, 1983 (p. 235, Ibid.) readily reveal

that the questioned signatures are the signatures of defendant

Segundo Dalion.

It may be noted that two signatures of Segundo D. Dalion appear

on the face of the questioned document (Exh. A), one at the right

corner bottom of the document (Exh. A-2) and the other at the left

hand margin thereof (Exh. A-3). The second signature is already a

surplusage. A forger would not attempt to forge another signature,

an unnecessary one, for fear he may commit a revealing error or an

erroneous stroke. (Decision, p. 10) (pp. 42-43, Rollo)

We see no reason for deviating from the appellate court's ruling (p. 44, Rollo) as we

reiterate that

Appellate courts have consistently subscribed to the principle that

conclusions and findings of fact by the trial courts are entitled to

great weight on appeal and should not be disturbed unless for

strong and cogent reasons, since it is undeniable that the trial court

is in a more advantageous position to examine real evidence, as

well as to observe the demeanor of the witnesses while testifying

in the case (Chase v. Buencamino, Sr., G.R. No. L-20395, May 13,

1985, 136 SCRA 365; Pring v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. L41605, August 19, 1985, 138 SCRA 185)

Assuming authenticity of his signature and the genuineness of the document, Dalion

nonetheless still impugns the validity of the sale on the ground that the same is

embodied in a private document, and did not thus convey title or right to the lot in

question since "acts and contracts which have for their object the creation,

transmission, modification or extinction of real rights over immovable property must

appear in a public instrument" (Art. 1358, par 1, NCC).

This argument is misplaced. The provision of Art. 1358 on the necessity of a public

document is only for convenience, not for validity or enforceability. It is not a

requirement for the validity of a contract of sale of a parcel of land that this be

embodied in a public instrument.

A contract of sale is a consensual contract, which means that the sale is perfected by

mere consent. No particular form is required for its validity. Upon perfection of the

contract, the parties may reciprocally demand performance (Art. 1475, NCC), i.e.,

the vendee may compel transfer of ownership of the object of the sale, and the

vendor may require the vendee to pay the thing sold (Art. 1458, NCC).

The trial court thus rightly and legally ordered Dalion to deliver to Sabesaje the

parcel of land and to execute corresponding formal deed of conveyance in a public

document. Under Art. 1498, NCC, when the sale is made through a public

instrument, the execution thereof is equivalent to the delivery of the thing. Delivery

may either be actual (real) or constructive. Thus delivery of a parcel of land may be

done by placing the vendee in control and possession of the land (real) or by

embodying the sale in a public instrument (constructive).

As regards petitioners' contention that the proper action should have been one for

specific performance, We believe that the suit for recovery of ownership is proper.

As earlier stated, Art. 1475 of the Civil Code gives the parties to a perfected contract

of sale the right to reciprocally demand performance, and to observe a particular

form, if warranted, (Art. 1357). The trial court, aptly observed that Sabesaje's

complaint sufficiently alleged a cause of action to compel Dalion to execute a formal

deed of sale, and the suit for recovery of ownership, which is premised on the

binding effect and validity inter partes of the contract of sale, merely

seeks consummation of said contract.

... . A sale of a real property may be in a private instrument but that

contract is valid and binding between the parties upon its

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 11

perfection. And a party may compel the other party to execute a

public instrument embodying their contract affecting real rights

once the contract appearing in a private instrument hag been

perfected (See Art. 1357).

The Case

Before us is a Petition for Review seeking to set aside the July 30, 1998 Decision of

the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. CV No. 38580, 1 which affirmed the

judgment2 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Cebu City. The CA ruled:

... . (p. 12, Decision, p. 272, Records)

ACCORDINGLY, the petition is DENIED and the decision of the Court of Appeals

upholding the ruling of the trial court is hereby AFFIRMED. No costs.

WHEREFORE, [there being] no error in the appealed decision, the same is

hereby AFFIRMED in toto.3

The decretal portion of the trial court Decision reads as follows:

SO ORDERED.

WHEREFORE, in view of all the foregoing [evidence] and considerations,

this court hereby finds the preponderance of evidence to be in favor of the

defendant Gerarda Selma as judgment is rendered:

1. Dismissing this Complaint for Quieting of title, Cancellation of

Certificate of Title of Gerarda vda. de Selma and damages,

2. Ordering the plaintiffs to vacate the premises in question and turn over

the possession of the same to the defendant Gerarda Selma;

G.R. No. 136021

February 22, 2000

BENIGNA SECUYA, MIGUEL SECUYA, MARCELINO

CORAZON SECUYA, RUFINA SECUYA, BERNARDINO

NATIVIDAD

SECUYA,

GLICERIA

SECUYA

and

SECUYA, petitioners,

vs.

GERARDA M. VDA. DE SELMA, respondent.

SECUYA,

SECUYA,

PURITA

3. Requiring the plaintiffs to pay defendant the sum of P20,000 as moral

damages, according to Art. 2217, attorney's fees of P15,000.00, litigation

expenses of P5,000.00 pursuant to Art. 2208 No. 11 and to pay the costs of

this suit.1wphi1.nt

SO ORDERED.4

Likewise challenged is the October 14, 1998 CA Resolution which denied

petitioners' Motion for Reconsideration.5

PANGANIBAN, J.:

The Facts

In action for quieting of title, the plaintiff must show not only that there is a cloud or

contrary interest over the subject real property, but that the have a valid title to it. In

the present case, the action must fail, because petitioners failed to show the requisite

title.

The present Petition is rooted in an action for quieting of title filed before the RTC

by Benigna, Miguel, Marcelino, Corazon, Rufina, Bernardino, Natividad, Gliceria

and Purita all surnamed Secuya against Gerarda M. vda. de Selma. Petitioners

asserted ownership over the disputed parcel of land, alleging the following facts:

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 12

xxx

xxx

xxx

8. The parcel of land subject of this case is a PORTION of Lot 5679 of the

Talisay-Minglanilla Friar Lands Estate, referred to and covered [o]n Page

279, Friar Lands Sale Certificate Register of the Bureau of Lands (Exh.

"K"). The property was originally sold, and the covering patent issued, to

Maxima Caballero Vda. de Cario (Exhs. "K-1"; "K-2). Lot 5679 has an

area of 12,750 square meters, more or less;

9. During the lifetime of Maxima Caballero, vendee and patentee of Lot

5679, she entered into that AGREEMENT OF PARTITION dated January

5, 1938 with Paciencia Sabellona, whereby the former bound herself and

parted [with] one-third (1/3) portion of Lot 5679 in favor of the latter (Exh.

"D"). Among others it was stipulated in said agreement of partition that the

said portion of one-third so ceded will be located adjoining the municipal

road (par. 5. Exh "D");

10. Paciencia Sabellona took possession and occupation of that one-third

portion of Lot 5679 adjudicated to her. Later, she sold the three thousand

square meter portion thereof to Dalmacio Secuya on October 20, 1953, for a

consideration of ONE THOUSAND EIGHT HUNDRED FIFTY PESOS

(P1,850.00), by means of a private document which was lost (p. 8, tsn.,

8/8/89-Calzada). Such sale was admitted and confirmed by Ramon

Sabellona, only heir of Paciencia Sabellona, per that instrument

denominated CONFIRMATION OF SALE OF UNDIVIDED SHARES,

dated September 28, 1976(Exh. "B");

11. Ramon Sabellona was the only [or] sole voluntary heir of Paciencia

Sabellona, per that KATAPUSAN NGA KABUT-ON UG PANUGON NI

PACIENCIA SABELLONA (Last Will and Testament of Paciencia

Sabellona), dated July 9, 1954, executed and acknowledged before Notary

Public Teodoro P. Villarmina (Exh. "C"). Pursuant to such will, Ramon

Sabellona inherited all the properties left by Paciencia Sabellona;

12. After the purchase [by] Dalmacio Secuya, predecessor-in interest of

plaintiffs of the property in litigation on October 20, 1953, Dalmacio,

together with his brothers and sisters he being single took physical

possession of the land and cultivated the same. In 1967, Edilberto Superales

married Rufina Secuya, niece of Dalmacio Secuya. With the permission and

tolerance of the Secuyas, Edilberto Superales constructed his house on the

lot in question in January 1974 and lived thereon continuously up to the

present (p. 8., tsn 7/25/88 Daclan). Said house is inside Lot 5679-C-12B, along lines 18-19-20 of said lot, per Certification dated August 10, 1985,

by Geodetic Engineer Celestino R. Orozco (Exh. "F");

13. Dalmacio Secuya died on November 20, 1961. Thus his heirs

brothers, sisters, nephews and nieces are the plaintiffs in Civil Case No.

CEB-4247 and now the petitioners;

14. In 1972, defendant-respondent Gerarda Selma bought a 1,000 squaremeter portion of Lot 5679, evidenced by Exhibit "P". Then on February 19,

1975, she bought the bigger bulk of Lot 5679, consisting of 9,302 square

meters, evidenced by that deed of absolute sale, marked as Exhibit "5". The

land in question, a 3,000-square meter portion of Lot 5679, is embraced and

included within the boundary of the later acquisition by respondent Selma;

15. Defendant-respondent Gerarda Selma lodged a complaint, and had the

plaintiffs-petitioners summoned, before the Barangay Captain of the place,

and in the confrontation and conciliation proceedings at the Lupong

Tagapayapa, defendant-respondent Selma was asserting ownership over the

land inherited by plaintiffs-petitioners from Dalmacio Secuya of which they

had long been in possession . . . in concept of owner. Such claim of

defendant-respondent Selma is a cloud on the title of plaintiffs-petitioners,

hence, their complaint (Annex "C").6

Respondent Selma's version of the facts, on the other hand, was summarized by the

appellate court as follows:

She is the registered owner of Lot 5679-C-120 consisting of 9,302 square

meters as evidenced by TCT No. T-35678 (Exhibit "6", Record, p. 324),

having bought the same sometime in February 1975 from Cesaria Caballero

as evidenced by a notarized Deed of Sale (Exhibit "5", Record, p. 323) and

ha[ve] been in possession of the same since then. Cesaria Caballero was the

widow of Silvestre Aro, registered owner of the mother lot, Lot. No. 5679

with an area of 12,750 square meters of the Talisay-Minglanilla Friar Lands

Estate, as shown by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 4752 (Exhibit "10",

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 13

Record, p. 340). Upon Silvestre Aro's demise, his heirs executed an

"Extrajudicial Partition and Deed of Absolute Sale" (Exhibit "11", Record,

p. 341) wherein one-half plus one-fifth of Lot No. 5679 was adjudicated to

the widow, Cesaria Caballero, from whom defendant-appellee derives her

title.7

The CA Ruling

In affirming the trial court's ruling, the appellate court debunked petitioners' claim of

ownership of the land and upheld Respondent Selma's title thereto. It held that

respondent's title can be traced to a valid TCT. On the other hand, it ruled that

petitioners anchor their claim on an "Agreement of Partition" which is void for being

violative of the Public Land Act. The CA noted that the said law prohibited the

alienation or encumbrance of land acquired under a free patent or homestead patent,

for a period of five years from the issuance of the said patent.

Hence, this Petition.8

The Issues

The Petition fails to show any reversible error in the assailed Decision.

Preliminary

The Action for Quieting of Title

Matter:

In an action to quiet title, the plaintiffs or complainants must demonstrate a legal or

an equitable title to, or an interest in, the subject real property.10 Likewise, they must

show that the deed, claim, encumbrance or proceeding that purportedly casts a cloud

on their title is in fact invalid or inoperative despite its prima facieappearance of

validity or legal efficacy.11 This point is clear from Article 476 of the Civil Code,

which reads:

Whenever there is cloud on title to real property or any interest therein, by

reason of any instrument, record, claim, encumbrance or proceeding which

is apparently valid or effective but is in truth and in fact invalid, ineffective,

voidable or unenforceable, and may be prejudicial to said title, an action

may be brought to remove such cloud or to quiet title.

An action may also be brought to prevent a cloud from being cast upon title

to real property or any interest therein.

In their Memorandum, petitioners urge the Court to resolve the following questions:

1. Whether or not there was a valid transfer or conveyance of one-third (1/3)

portion of Lot 5679 by Maxima Caballero in favor of Paciencia Sabellona,

by virtue of [the] Agreement of Partition dated January 5, 1938[;] and

2. Whether or not the trial court, as well as the court, committed grave

abuse of discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction in not making a finding

that respondent Gerarda M. vda. de Selma [was] a buyer in bad faith with

respect to the land, which is a portion of Lot 5679.9

For a clearer understanding of the above matters, we will divide the issues into

three: first, the implications of the Agreement of Partition; second, the validity of the

Deed of Confirmation of Sale executed in favor of the petitioners; and third, the

validity of private respondent's title.

The Court's Ruling

In the case at bar, petitioners allege that TCT No. 5679-C-120, issued in the name of

Private Respondent Selma, is a cloud on their title as owners and possessors of the

subject property, which is a 3,000 square-meter portion of Lot No. 5679-C-120

covered by the TCT. But the underlying question is, do petitioners have the requisite

title that would enable them to avail themselves of the remedy of quieting of title?

Petitioners anchor their claim of ownership on two documents: the Agreement of

Partition executed by Maxima Caballero and Paciencia Sabellona and the Deed of

Confirmation of Sale executed by Ramon Sabellona. We will now examine these two

documents.

First

The Real Nature of the "Agreement of Partition"

Issue:

The duly notarized Agreement of Partition dated January 5, 1938; is worded as

follows:

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 14

AGREEMENT OF PARTITION

I, MAXIMA CABALLERO, Filipina, of legal age, married to Rafael

Cario, now residing and with postal address in the Municipality of

Dumaguete, Oriental Negros, depose the following and say:

1. That I am the applicant of vacant lot No. 5679 of the Talisay-Minglanilla

Estate and the said application has already been indorsed by the District

Land Officer, Talisay, Cebu, for private sale in my favor;

2. That the said Lot 5679 was formerly registered in the name of Felix Abad

y Caballero and the sale certificate of which has already been cancelled by

the Hon. Secretary of Agriculture and Commerce;

3. That for and in representation of my brother, Luis Caballero, who is now

the actual occupant of said lot I deem it wise to have the said lot paid by

me, as Luis Caballero has no means o[r] any way to pay the government;

4. That as soon as the application is approved by the Director of Lands,

Manila, in my favor, I hereby bind myself to transfer the one-third (l/3)

portion of the above mentioned lot in favor of my aunt, Paciencia Sabellana

y Caballero, of legal age, single, residing and with postal address in

Tungkop, Minglanilla, Cebu. Said portion of one-third (1/3) will be

subdivided after the approval of said application and the same will be paid

by her to the government [for] the corresponding portion.

5. That the said portion of one-third (1/3) will be located adjoining the

municipal road;

6. I, Paciencia Sabellana y Caballero, hereby accept and take the portion

herein adjudicated to me by Mrs. Maxima Caballero of Lot No. 5679

Talisay-Minglanilla Estate and will pay the corresponding portion to the

government after the subdivision of the same;

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, we have hereunto set our hands this 5th day of

January, 1988, at Talisay, Cebu."12

The Agreement: An Express Trust, Not a Partition

Notwithstanding its purported nomenclature, this Agreement is not one of partition,

because there was no property to partition and the parties were not co-owners.

Rather, it is in the nature of a trust agreement.

Trust is the right to the beneficial enjoyment of property, the legal title to which is

vested in another. It is a fiduciary relationship that obliges the trustee to deal with the

property for the benefit of the beneficiary.13 Trust relations between parties may

either be express or implied. An express trust is created by the intention of the trustor

or of the parties. An implied trust comes into being by operation of law.14

The present Agreement of Partition involves an express trust. Under Article 1444 of

the Civil Code, "[n]o particular words are required for the creation of an express

trust, it being sufficient that a trust is clearly intended." That Maxima Caballero

bound herself to give one third of Lot No. 5629 to Paciencia Sabellona upon the

approval of the former's application is clear from the terms of the Agreement.

Likewise, it is evident that Paciencia acquiesced to the covenant and is thus bound to

fulfill her obligation therein.

As a result of the Agreement, Maxima Caballero held the portion specified therein as

belonging to Paciencia Sabellona when the application was eventually approved and

a sale certificate was issued in her name. 15 Thus, she should have transferred the

same to the latter, but she never did so during her lifetime. Instead, her heirs sold the

entire Lot No. 5679 to Silvestre Aro in 1955.

From 1954 when the sale certificate was issued until 1985 when petitioners filed

their Complaint, Paciencia and her successors-in-interest did not do anything to

enforce their proprietary rights over the disputed property or to consolidate their

ownership over the same. In fact, they did not even register the said Agreement with

the Registry of Property or pay the requisite land taxes. While petitioners had been

doing nothing, the disputed property, as part of Lot No. 5679, had been the subject of

several sales transactions16 and covered by several transfer certificates of title.

The Repudiation of the Express Trust

While no time limit is imposed for the enforcement of rights under express

trusts,17 prescription may, however, bar a beneficiary's action for recovery, if a

repudiation of the trust is proven by clear and convincing evidence and made known

to the beneficiary.18

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 15

There was a repudiation of the express trust when the heirs of Maxima Caballero

failed to deliver or transfer the property to Paciencia Sabellona, and instead sold the

same to a third person not privy to the Agreement. In the memorandum of

incumbrances of TCT No. 308719 issued in the name of Maxima, there was no

notation of the Agreement between her and Paciencia. Equally important, the

Agreement was not registered; thus, it could not bind third persons. Neither was

there any allegation that Silvestre Aro, who purchased the property from Maxima's

heirs, knew of it. Consequently, the subsequent sales transactions involving the land

in dispute and the titles covering it must be upheld, in the absence of proof that the

said transactions were fraudulent and irregular.

Deed21 confirming the sale executed by Ramon Sabellona, Paciencia's alleged heir.

The testimony of Miguel was a bare assertion that the sale had indeed taken place

and that the document evidencing it had been destroyed. While the Deed executed by

Ramon ratified the transaction, its probative value is doubtful. His status as heir of

Paciencia was not affirmatively established. Moreover, he was not presented in court

and was thus not quizzed on his knowledge or lack thereof of the 1953

transaction.

Petitioners' Failure to Exercise Owners'

Rights to the Property

Second

The Purported Sale to Dalmacio Secuya

Issue:

Even granting that the express trust subsists, petitioners have not proven that they are

the rightful successors-in-interest of Paciencia Sabellona.

The Absence of the Purported Deed of Sale

Petitioners insist that Paciencia sold the disputed property to Dalmacio Secuya on

October 20, 1953, and that the sale was embodied in a private document. However,

such document, which would have been the best evidence of the transaction, was

never presented in court, allegedly because it had been lost. While a sale of a piece of

land appearing in a private deed is binding between the parties, it cannot be

considered binding on third persons, if it is not embodied in a public instrument and

recorded in the Registry of Property.20

Moreover, while petitioners could not present the purported deed evidencing the

transaction between Paciencia Sabellona and Dalmacio Secuya, petitioners'

immediate predecessor-in-interest, private respondent in contrast has the necessary

documents to support her claim to the disputed property.

Petitioners insist that they had been occupying the disputed property for forty-seven

years before they filed their Complaint for quieting of title. However, there is no

proof that they had exercised their rights and duties as owners of the same. They

argue that they had been gathering the fruits of such property; yet, it would seem that

they had been remiss in their duty to pay the land taxes. If petitioners really believed

that they owned the property, they have should have been more vigilant in protecting

their rights thereto. As noted earlier, they did nothing to enforce whatever proprietary

rights they had over the disputed parcel of land.

Third

The Validity of Private Respondent's Title

Issue:

Petitioners debunk Private Respondent Selma's title to the disputed property, alleging

that she was aware of their possession of the disputed properties. Thus, they insist

that she could not be regarded as a purchaser in good faith who is entitled to the

protection of the Torrens system.

Indeed, a party who has actual knowledge of facts and circumstances that would

move a reasonably cautious man to make an inquiry will not be protected by the

Torrens system. In Sandoval v. Court of Appeals,22 we held:

The Questionable Value of the Deed

Executed by Ramon Sabellona

To prove the alleged sale of the disputed property to Dalmacio, petitioners instead

presented the testimony of Miguel Secuya, one of the petitioners; and a

It is settled doctrine that one who deals with property registered under the

Torrens system need not go beyond the same, but only has to rely on the

title. He is charged with notice only of such burdens and claims as are

annotated on the title.

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 16

The aforesaid principle admits of an unchallenged exception: that a person

dealing with registered land has a right to rely on the Torrens certificate of

title and to dispense without the need of inquiring further except when the

party has actual knowledge of facts and circumstances that would impel a

reasonably cautious man to make such inquiry, or when the purchaser has

knowledge of a defect or the lack of title in his vendor or of sufficient facts

to induce a reasonably prudent man to inquire into the status of title of the

property in litigation. The presence of anything which excites or arouses

suspicion should then prompt the vendee to look beyond the certificate and

investigate the title of the vendor appearing on the face of the certificate.

One who falls within the exception can neither be denominated an innocent

purchaser for value purchaser in good faith; and hence does not merit the

protection of the law.

Granting arguendo that private respondent knew that petitioners, through Superales

and his family, were actually occupying the disputed lot, we must stress that the

vendor, Cesaria Caballero, assured her that petitioners were just tenants on the said

lot. Private respondent cannot be faulted for believing this representation,

considering that petitioners' claim was not noted in the certificate of the title covering

Lot No. 5679.

Moreover, the lot, including the disputed portion, had been the subject of several

sales transactions. The title thereto had been transferred several times, without any

protestation or complaint from the petitioners. In any case, private respondent's title

is amply supported by clear evidence, while petitioners' claim is barren of proof.

Clearly, petitioners do not have the requisite title to pursue an action for quieting of

title.1wphi1.nt

WHEREFORE, the Petition is hereby DENIED and the assailed Decision

AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioners.

SO ORDERED.

G.R. No. L-55048 May 27, 1981

SUGA SOTTO YUVIENCO, BRITANIA SOTTO, and MARCELINO

SOTTO, petitioners,

vs.

HON. AUXENCIO C. DACUYCUY, Judge of the CFI of Leyte, DELY

RODRIGUEZ, FELIPE ANG CRUZ, CONSTANCIA NOGAR, MANUEL GO,

INOCENTES DIME, WILLY JULIO, JAIME YU, OSCAR DY, DY CHIU

SENG, BENITO YOUNG, FERNANDO YU, SEBASTIAN YU, CARLOS UY,

HOC CHUAN and MANUEL DY,respondents.

SALES AUGUST 6, 2015 17

BARREDO, J.:1wph1.t

Petition for certiorari and prohibition to declare void for being in grave abuse of

discretion the orders of respondent judge dated November 2, 1978 and August 29,

1980, in Civil Case No. 5759 of the Court of First Instance of Leyte, which denied

the motion filed by petitioners to dismiss the complaint of private respondents for

specific performance of an alleged agreement of sale of real property, the said

motion being based on the grounds that the respondents' complaint states no cause of

action and/or that the claim alleged therein is unenforceable under the Statute of

Frauds.

Finding initially prima facie merit in the petition, We required respondents to answer

and We issued a temporary restraining order on October 7, 1980 enjoining the

execution of the questioned orders.

In essence, the theory of petitioners is that while it is true that they did express

willingness to sell to private respondents the subject property for P6,500,000

provided the latter made known their own decision to buy it not later than July 31,

1978, the respondents' reply that they were agreeable was not absolute, so much so