Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Variation in German by S Barbour

Uploaded by

Nandini1008Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Variation in German by S Barbour

Uploaded by

Nandini1008Copyright:

Available Formats

362 Variation in German

Variation in German

S Barbour, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK

2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

An examination of German immediately reveals unusual geographical and social variation in the language. Varieties labeled as deutsch/German are often

not mutually intelligible, as witnessed by the use

of subtitles in Swiss-German films shown to audiences in Germany. German-speakers regularly report

comprehension difficulties when visiting Germanspeaking areas distant from their homes. There is a

good case for seeing German as the most variable

language in Europe.

German in Geopolitical Context

German includes most of the Continental West Germanic dialect continuum that, before the Germans

lost territory in the 20th century, stretched from

Dunkirk in France to beyond Vienna and beyond

Ko nigsberg/Kaliningrad in East Prussia (now in the

enclave of Russia between Poland and Lithuania).

Beyond that continuum are, or were, enclaves of

German speech in most Central and Eastern European countries and in the former Soviet Union, as far

away as Kazakhstan and Siberia. By dialect continuum, I mean a language area where basilectal dialect

speech changes slightly from place to place over a

wide area, with perhaps noticeable differences even

from one village to the next, with poor comprehensibility between the speech of places fifty to a hundred

kilometers apart, and with possibly no comprehensibility between the varieties at the ends of the continuum. Such continua may include several languages, for

example, Western Romance (including French,

Catalan [Catalan-Valencian-Balear], Castilian Spanish

[Spanish], Italian, Portuguese, Occitan [Auvergnat,

Gascon, Languedocien, Limousin], and others) or

South Slavonic (including Slovene [Slovenian], Croatian [Serbo-Croatian], Serbian [Serbo-Croatian],

Macedonian, and Bulgarian).

Although comparable in size and in variability to

the Western Romance and South Slavonic continua,

the Continental West Germanic continuum is unusual

because in the minds of most speakers of the relevant

dialects, it includes only two languages, German and

Dutch. One of these, German, occupies the overwhelmingly greater part of the territory in question

and exhibits virtually the full range of variability

found in the continuum. Other large continua in

modern times have been divided into a greater number of distinct languages as the people in question

have become divided into religious, regional, cultural,

and ethnic groups, in other words, nations. Occupying different parts of the continuums territory, such

groups then developed the concept of distinct languages, linked to distinct processes of standardization. One only need think of Western Romance

divided into the clearly distinct French, Spanish,

Italian, and Portuguese (and others).

Some speakers of different languages within continua may be quite unaware of their continuums

existence, but speakers of German often see the Continental West Germanic continuum clearly, even seeing its division into Dutch and German as anomalous.

It is not uncommon to find speakers of German

who regard Dutch as a German dialect. An outside

observer well versed in the Continental West Germanic linguistic situation will not see the separation

of Dutch as a distinct language as anomalous. For this

observer, the contentious questions lie elsewhere:

(1) in the development and persistence of the idea of

a single language within the greater part of the large

and linguistically diverse Continental West Germanic

continuum; (2) in the development of the idea of

a single nation, Germany, in such a large, diverse

geographical area and in such a diverse population;

(3) in the slow, incomplete, and fraught separation

between Germany and Austria, with its parallel linguistic separation falling far short of a division into

different languages; (4) in the development of a kind

of linguistic independence in German-speaking

Switzerland that is mainly found in spoken language;

(5) in the development of a distinct but closely related

language in Luxembourg that plays a role (along with

French) in national identity; with German, fulfills

important utilitarian functions in Luxembourg; (6) in

the strong persistence of regional and local dialect in

the entire German-speaking area, particularly in the

Centre and South; (7) in the strong significance, despite its diversity, of the language for German national identity, but also for Austrian national identity;

and (8) in the occurrence of a small number of West

Germanic Frisian dialects in the northwest, spoken by

bilinguals who also use either Dutch or German the

Frisian dialects not being part of the continuum.

The main points of interest in the part of the

Continental West Germanic continuum known as

German are (1) the scope of dialectal diversity;

(2) the relationship between the standard language

and other varieties; and (3) the variation within the

standard language. Fuller discussion of the tension

between the diversity of German and its role in national and ethnic identity and the complex relationships between German and other languages can be

found elsewhere, for example in Clyne (1995),

Variation in German 363

Barbour and Stevenson (1990: 2354), Barbour and

Stevenson (1998: 2559), and Barbour (2000a).

Dialekt, Colloquial, and Standard Varieties

When discussing dialectal diversity in German, it is

important to understand that dialect/Dialekt in

works on German sociolinguistics usually means

basilectal dialect, in other words, the regional dialect

that is maximally distinct from the standard language. This contrasts with the usage of dialect in

English to indicate any form of a language that differs

appreciably in grammar or lexicon from other forms

of the language. Dialect in this sense in English may

or may not include the standard language. For the

sake of clarity, in this article dialect/Dialekt in the

German sense will be referred to as traditional dialect. Where such traditional dialects as recorded in

the early 20th century, or before, have now been

radically modified or replaced, German works may

describe the area in question as free of dialect. This

could suggest to a non-German reader a place where

everyone speaks the standard language, which is virtually never the case. In such areas, and elsewhere,

a great deal of speech lies between the standard language and the traditional dialect; in German it is

labeled Umgangssprache, which I term colloquial

speech. Such colloquial speech includes varieties

that, in English would be termed dialect, at one

end of the scale, or informal or colloquial standard

language, at the other. For the sake of clarity, I divide

colloquial speech into colloquial standard language

and colloquial nonstandard language; the latter

generally corresponds to dialect in works written

in English. [This terminology is outlined in full

in Barbour and Stevenson 1990: 133146; also see

Barbour 1999).] In German sociolinguistics there has

been relative neglect of colloquial language, exceptions being the work of Ju rgen Eichhoff (1977, 1978)

and of some East German scholars such as Helmut

Scho nfeld (see Barbour 2000b); this neglect extends

to registers that I am labeling colloquial standard

language. Work on German standard language

(Standardsprache or Hochsprache) tends to refer

chiefly to the rather more formal registers, which

I discuss here as formal standard language.

This article will compare traditional German dialects with the formal standard language, following

the common assumption that other forms of the

language represent compromises between these two

ends of the spectrum of variation. Since this assumption is very crude and incorrect in many matters

of detail, more detail on other varieties (and hence,

corrections), will be provided as necessary.

Our discussion will start with phonetics and phonology (sounds), moving on to the morphology of

the noun phrase and of the verb phrase. Except

where otherwise stated, further detail about all of

the phenomena discussed can be found in Barbour

and Stevenson (1990: 5599, 133180); Barbour and

Stevenson (1998: 60107, 145198); and Russ (1989).

German Dialect Continuum

Descriptions of German dialects almost always

divide the dialects into three geographical groups:

Low German/Niederdeutsch, Central German/Mitteldeutsch, and Upper German/Oberdeutsch. Central

German and Upper German may be grouped together

as High German/Hochdeutsch, these last two terms

being ambiguous since they are also used to refer to

the standard language.

The Low German dialect area lies north of a line

crossing the Rhine at Benrath just south of Du sseldorf

(the Benrath line) and running in a roughly east-west

direction across the entire German-speaking territory,

passing to the south of Berlin, and crossing the river

Oder south of Frankfurt an der Oder on the Polish

border. Insofar as dialect, in the German sense, can

be found there at all, Berlin can be seen as an island (or

perhaps peninsula) of Central German speech in Low

German territory. Some German accounts include

Dutch in the Low German dialect area but, although

Dutch and Low German are linguistically close, sociolinguistically it is untenable that Dutch is a Low German dialect. The Low German dialects are arguably

the group of German dialects that differ most markedly from the standard language. This is not surprising

since the standard language historically derives chiefly

from central and southern dialects. The Low German/

Niederdeutsch dialect area is characterized by the

relative weakness of the traditional dialects, popularly

labeled Plattdeutsch; indeed, it is perhaps fair to say

that the region is seen by other German speakers as a

bastion of the standard language.

Serious scholarship presents a much modified view;

according to Stellmacher (1997), the rural parts of the

region may have levels of usage of traditional dialect

as high as some parts of the Centre and South. What

is true is that most urban speech in North Germany is

very clearly not traditional dialect, whereas in southern areas even quite large towns may contain many

speakers whose usage is close to the traditional dialect; to northerners, southern urban speakers sound

like dialect speakers, whereas to southerners, northern urban speakers sound like standard speakers.

However, northern urban speech is very frequently

not standard in the sense that this is understood in

Germany; in other words, it is generally not formal

standard language.

South of Low German, Central German dialects

are divided from Upper German dialects by a line

364 Variation in German

that crosses the Rhine south of Mainz, then runs

northeastwards, to the south of Frankfurt am Main

and to the north of Wu rzburg and Bamberg, running

then roughly eastwards to the border with the Czech

Republic. The Germanic speech of Luxembourg,

formerly described as a Central German dialect/Mitteldeutscher Dialekt in texts produced in Germany,

is considered by its speakers to represent a distinct

language, Le tzebuergesch/Luxembourgish (Luxembourgeois). This is sociolinguistically well justified,

as Luxembourgish is used by all sections of indigenous society and has a standardized written form (for

the linguistic situation in Luxembourg, see Newton

1989: 145149).

The Germanic speech of Alsace-Lorraine in France

is almost universally regarded in Germany as German

dialects the northern ones Central German, with

Upper German to the south but a common view in

France (both official and popular) is that these represent a distinct Germanic language called Alsatian/

alsacien. Sociolinguistically the situation is complex;

in support of dialect status, there is no accepted single

standard form of Alsatian, but then again, in support

of independent status, speakers of Alsatian often do

not know standard German.

In the Central German and Upper German dialect

areas, the social status of dialects and other nonstandard speech becomes generally higher the farther

south we travel, although throughout the territory,

traditional dialects are stronger in rural than in

urban areas. The strength of traditional dialects is particularly notable in German-speaking Switzerland,

where these are used by all sections of society. The

link between language varieties and social status is

much less clear in German-speaking than in Englishspeaking countries. Nevertheless, the link between

grammatically nonstandard forms and low socioeconomic status is fairly clear in North and Central

Germany.

Phonetic and Phonological Variation

In our discussion of German pronunciation (phonetics and phonology), orthography will be used, rather

than phonemic transcription, since German orthography is a reasonably good guide to pronunciation. In

phonetics and phonology, the most striking difference

within German is between Low German, on the one

hand, and the standard language and Central and

Upper German dialects, on the other. Across the

entirety of the basic lexicon of the language we find

plosives in Low German corresponding to fricatives

or affricates (or sequences of plosive plus fricative) in

the other varieties. For example, corresponding to

standard German Pfund (pound), Apfel (apple), hoffen (hope [verb]), zwei (two), Katze (cat), das (the/

that), Buch (book), (orthographic z and tz correspond

to the sequence /ts/; orthographic ch corresponds to

the velar fricative /x/ or the palatal fricative /c /), we

find Low German forms such as Pund, Appel, hopen,

twee, Kat, dat, Book. (There is no standard orthography for Low German; forms given here are merely a

guide to typical pronunciations.) The distinct Low

German forms seem to be conceptualized not just as

differing in pronunciation from the standard forms,

but as different lexical items, in other words, as dialect vocabulary; these are not found regularly in the

colloquial speech of North Germany.

This difference between Low German and standard

German arises from the operation of the second or

High German sound shift in the Old High German

dialects (from which standard German is mainly

derived) towards the end of the first millennium A.D.

The difference, which can be a severe impediment to

comprehension, is of the kind frequently found between distinct but related languages; one might think

of the contrast between words such as cent and chateau in French, with initial /s/ and /S/ respectively,

and cento and castello in Italian, with /tS/ and /k/

respectively. Partly because of the low comprehensibility between standard German and Low German, it

is often thought of as a distinct language and, up until

the 17th century [before modern standard (High) German came to be accepted as the prestige variety in the

territory], a distinct process of standardization was

under way for Low German. Low German is today

recognized as a regional minority language, not

simply as dialects of German (see Stellmacher, 1997).

The most common difference in consonants between Central and Upper German dialects, on the

one hand, and the standard language, on the other,

can be discussed under the heading of lenition. In the

dialects in question, voiceless plosives can be seen as

having been softened to make them approach voiced

plosives in sound (though it is not at all clear, historically, that anything quite like this happened), with the

two series even becoming identical. The resultant

sounds are generally lenis, i.e., soft, like the voiced

plosives of standard German (and of standard

English) but without vocal chord vibration, in this

resembling the voiceless plosives of standard German

(and of standard English). These resultant sounds are

spelled, in popularly impressionistic dialect orthography, with the symbols normally used for voiced

plosives, i.e., b, d, and g. In some dialects, for example

in much of East Central German, the distinction

between voiced and voiceless plosives is largely absent,

so that a word pair Karten/Garten may be homophones. In other dialects the distinction may be

present, but the voiced and voiceless sounds may

have a distribution different from that in the standard

language; in some dialects the voiceless sounds are

Variation in German 365

found more commonly in words of relatively recent

foreign origin, with the voiced (or lenis voiceless)

sounds elsewhere for example, in Alemannic dialects

for standard German dir (you, familiar, singular), Tier

(animal), and Theater (with an initial t sound) (theatre), we may find dir, and Dier, but Theater (again

with an initial t sound). Lenition is found in most of

Central German apart from some western and central northern areas and in the northern part of Upper

German. As well as being a feature of traditional dialect, lenition phenomena are usually also found (at

least to some degree) in colloquial speech in the regions

in question.

Except where lenition phenomena occur, Central

and Upper German dialects are generally somewhat

closer to the standard language in consonant phonology than are Low German dialects. However, in particular phonetic environments or in certain individual

words, forms resembling the Low German forms are

found in Central German dialects. For example, in

much of western Central German, dat (that, the) and

wat (what) correspond to the standard German (and

Upper German) das and was. Throughout Central

German, p corresponds to standard German pf both

medially and finally in words, so Appel is found

where standard German (and Upper German) have

forms like Apfel. West Central German, also has p,

which corresponds to the initial pf in standard

German words, for example, having Pund for the

standard German Pfund. Interestingly enough,

forms like dat, wat, Appel, and Pund are found in

Central German colloquial nonstandard speech as

well as in traditional dialect.

We noted above the many instances where Low

German dialects have plosives, whereas Central and

Upper German dialects and the standard language

have fricatives or affricates. However, in the case of

the velar obstruents in a words initial position, most

forms of German have only plosives, with Low

German Kat and standard German Katze agreeing

in initial consonant. In contrast, southern Upper

German dialects have affricates or fricatives in

the initial position of such words: for example, a

common Swiss equivalent of Katze is Chatz, where

orthographic Ch- represents a velar affricate /kx/.

It is difficult to say if this Upper German feature

is found in colloquial speech, since this regions

everyday language already uses overwhelmingly traditional dialect anyway, or varieties very close to this.

A further feature widespread in Central and Upper

German dialects is an absence of the front rounded

vowels, corresponding to orthographic <u > and <o >,

found in standard German and in Low German; front

unrounded vowels are found instead. The following

pairs of distinct words in standard German could in

the relevant varieties be homophones: (1) vier (four)

and fu r (for) and Sehne (tendon) and So hne (sons).

(In reality, the situation is usually more complex

than this; the examples are intended only as a guide

to what can happen.) The absence of front rounded

vowels is a feature of both traditional dialect and

colloquial nonstandard language.

Varieties of German have many other differences in

vowel sounds. One important one clearly separates

dialect, on the one hand, from standard and colloquial speech, on the other. Most Low German dialects,

but also many others, particularly in the Southwest

(including Switzerland) have monophthongs /i:/ and

/u:/ where the standard language, and other varieties,

have diphthongs. Examples are southwestern Ziet

and Hus for standard Zeit and Haus.

In some West Central German dialects, and in Luxembourgish, contrasts between words are effected

not only by differences between vowels and consonants, but also by tonal differences, a phenomenon

common in the languages of the world, but rare in

Europe, where the best-known examples are found in

Norwegian and Swedish. Though neither widespread

nor well known to German-speakers as a whole, this

feature underlines the extraordinary diversity of

German dialects. (For discussion of tonal contrasts

see Newton, 1989: 153156, where he terms the

phenomenon correption.)

Syntactic and Semantic Variation

Traditional German dialects also clearly differ from

standard German in grammatical structure, most notably in the noun phrase and the verb phrase. For

example, where standard German has four morphologically distinct cases in the noun phrase, Low

German has only two, which we may term nominative and oblique. In all continental West Germanic

speech, apart from formal standard German, morphologically distinct genitive cases are now rare;

however, Losses of other case distinctions are quite

highly stigmatized and uncommon in colloquial

language.

Differences between varieties of German in

the noun phrase represent quite striking typological

differences between more and less highly inflected

types of language, differences that elsewhere might

be associated with the distinction between one

language and another.

In the verb phrase, distinctions found in the formal

standard language may be absent in other varieties or

may be conveyed in different ways. Most notably, a

semantic distinction between the two past tenses,

perfect and preterite, the latter also known as simple

past or imperfect, is probably now in doubt in almost

all varieties of German in most contexts; for example,

ich sah ihn (preterite) and ich habe ihn gesehen

366 Variation in German

(perfect) (both translating as either I saw him or I

have seen him) are generally entirely synonymous,

but with the former being stylistically marked as

more formal. In North and Central German speech,

in both Low German and Central German dialects,

and in colloquial language, preterite forms are found,

but the only common ones are those of modal and

other auxiliary verbs and a few others, for example:

war, hatte, musste, mochte, sollte, wollte, konnte,

durfte, wurde, sagte, meinte. In the regions in question, and for these particular verbs, those may actually be the most common past tense forms; for almost

all other verbs, perfect forms are much more common, with preterite forms generally being formal or

highly formal in register. Given that the preterite and

perfect forms are generally synonymous, these labels

are misleading; it would make more sense to talk, for

example, about simple and periphrastic past forms.

I continue, however, to use the terms preterite and

perfect, since they are so well established.

In the South German speech of Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, particularly in Upper German dialects, preterite forms of any verbs are entirely absent,

being replaced by perfect forms. As preterites are not

found in everyday speech in these regions, they are

regarded as highly formal, and children have to be

taught these in school.

The presence in some varieties of German of a

tense/aspect distinction, which is absent in others,

again represents the kind of radical differences that

elsewhere could correlate with the distinction between one language and another.

Dialects and colloquial speech also differ from formal standard language in the occurrence of subjunctive forms. The formal standard language has two sets

of subjunctive forms, first and second subjunctive.

Each of these has two tenses, which I will term as

nonpast and past. For example, from the verbs

kaufen (buy) and fahren (travel) first subjunctive nonpast forms are er kaufe and er fahre (contrasting with

indicative or normal forms of these verbs, er kauft,

er fa hrt), and past forms are er habe gekauft and er

sei gefahren (contrasting with indicative forms of

these verbs, er hat gekauft, er ist gefahren). These

first subjunctive forms are usually termed present

subjunctive and perfect subjunctive, respectively.

Second subjunctive forms of these verbs are (1) er

kaufte and er fu hre (nonpast) and (2) er ha tte gekauft

and er wa re gefahren (past). These second subjunctive

forms are usually termed imperfect subjunctive and

pluperfect subjunctive, respectively, but such terms

are highly misleading because they are not imperfect

or pluperfect in tense/aspect reference.

In the formal standard language, first subjunctives

are used in reported speech, particularly when speak-

ers or, much more frequently, writers wish to distance

themselves from the information in other words,

to indicate that the information may not necessarily

be true (without calling the user of the original words

a liar); the first subjunctive is hence very popular

with journalists. The first subjunctive is clearly formal, and it is not used in colloquial speech or in

dialect, being replaced by the indicative, or by the

second subjunctive where the distancing effect is

clearly desired.

Many second subjunctive forms are also formal,

indeed, highly formal or rare or archaic. In the case

of nonpast forms like kaufte, they are avoided because they are identical to indicatives of the same

verbs. In fact, the only common subjunctive forms

in German are past tenses like er ha tte gekauft and

er wa re gefahren and the nonpast forms of modal and

other auxiliary verbs: wa re, ha tte, mu sste, mo chte,

sollte, wollte, ko nnte, du rfte, wu rde with dialect

and colloquial nonstandard so llte and wo llte often

replacing sollte and wollte. Nonpast subjunctives of

other verbs are formed on the following pattern:

wu rde kaufen, wu rde fahren. These common subjunctive forms are indeed very common, being used

to express hypotheses and, along with modal particles

and particular lexical items, are the main way to

express all types of modality such as supposition,

doubt, and volition; the other major function is in

conveying politeness. The use of subjunctives is a

characteristic of all types of German, but the range

of forms is a major indicator of the dividing line

between the formal standard and other varieties.

This difference in the range of forms is again

of quite a radical kind, which elsewhere would be

associated with differences between languages.

Causes of Variation

In discussing the variation in German, it is tempting

to assume that colloquial language represents simply

a kind of compromise between the standard language

and traditional dialects and, hence, that description of

the dialects can form the basis of a full account of

variation. However, it is clear from the above account

that such an assumption would lead to considerable

oversimplification (see Barbour and Stevenson 1998:

156157, 1990: 146147). There is strong evidence of

cases where developments in the colloquial language

are independent of phenomena in traditional dialect;

for example the uvular r sound [R], originally not

considered part of formal standard, is now gaining

ground everywhere in Germany and Austria, even

in regions where it is not found in traditional dialect.

A loss of the distinction between /c / and /S/, as found

at the ends of the standard German words ich

Variation in German 367

and Fisch, is spreading in Central German colloquial speech, even in areas where the distinction is

maintained in traditional dialect.

The idea of straightforward contact or interference

phenomena used to be popular in discussions of varieties that arise from language contact. Such a variety,

guest worker German (Gastarbeiterdeutsch), the

German of immigrant workers and their families, was

found in fact not to result in any simple way from

contact between German and the immigrant workers

first language (see Barbour and Stevenson 1998:

211223, 1990: 192203). Gastarbeiterdeutsch is

characterized (1) by lack of verbal inflections, with

forms like infinitives being used throughout, while

the languages in contact generally have verbal inflections; (2) by verbal-final word order, found only in

Turkish (and to a limited extent in German itself)

among the contact languages; and (3) by absence of

gender distinctions, this being only a characteristic

of Turkish. It must be stressed that these phenomena

are found in the German of speakers of all of the

contact languages, including those who have no contact with Turkish speakers. Among second and third

generation immigrants, guest worker German is now

of very limited importance. Their speech is characterized by code switching between German and another

language, a phenomenon that goes beyond our topic

of variation in German.

Lexical Variation

The differences within German discussed so far tend

to separate the formal standard language from other

varieties, while also having important regional

dimensions. When considering lexical differences,

the regional dimension is all-important. In lexical

differences, however, the pattern is extremely complex, and a full discussion would far exceed the limits

of this article; I shall therefore make only a few salient

points. (For further information see Eichhoff (1987,

1988); and Ko nig 1978). As in other facets of the

language, German is surprisingly diverse; there are

differences between lexical items of related meaning

that in other language groups may be cognate across a

number of different languages. For example, different

varieties of German have different names for days

of the week, which, in contrast, are clearly cognate

across the entire Western Romance group of languages. Erchtag (Bavarian-Austrian dialects), Ziestag

(some other southern dialects, including Swiss dialects), and Dienstag (other regions and the standard

language) all refer to Tuesday; Sonnabend (standard language and other varieties North), Samstag

(standard language and other varieties South), and

Saterdag (some northwestern dialects), all refer to

Saturday. Southwestern dialects even have a regional

word for father, Atti, contrasting with the general

Vater/Vader, the latter having cognates across the

entire, vast Indo-European language family.

There are even regional varieties of pronouns,

a phenomenon that causes serious comprehension

difficulties, for example, forms like he, him (English

he, him, it) in Low German and some Central

German dialects where the standard language and

southern dialects have forms such as er, ihn, ihm.

Many Bavarian dialects have forms like o s/es, enk

while the standard language and other dialects have

forms such as ihr, euch (you plural familiar forms).

These pronouns variants are restricted to traditional

dialect (although there are traces of the Bavarian o s/es

forms in colloquial language), but a further regional

variant, mir, where the standard has wir (we), is

extremely widespread in both colloquial language

and dialect in the South.

In looking at the variation in German, it is important to remember that the language is a major factor

in defining German national identity. This was

particularly so before the political unification of

Germany in 1871 and during the years of the division

in Germany between 1949 and 1990. In the Germanspeaking area before 1871, the immensely diverse

dialects were unable to function as symbols of national unity, so this role fell to the standard language.

Perhaps this is why many German speakers are anxious about diversity in the standard language there

is a feeling it should be the same everywhere. In

paradoxical contrast, dialect diversity, which is prized

as the symbol of local or regional identity, is also

extremely important to German speakers, probably

because of the late achievement of national political

unity. Given its number of users, standard German

is inevitably diverse, particularly in the lexicon, but

there is often a kind of grassroots feeling that this

should not be so. The major lexical divide is a NorthSouth one, but with precise boundaries between

northern and southern forms lying in different places

for different items; common examples would be

southern Ross and Bursche compared with northern

Pferd and Junge (horse and boy) and the variants

for Saturday already given. A particularly salient

difference is that between northern Guten Tag and

southern Gru ss Gott (good day, hello). The so-called

diminutive suffix, which actually has a wide variety of

pragmatic as well as semantic functions, also divides

North from South, with northern and central -chen,

southeastern -erl or -el, and southwestern -le or -li. The

formal standard language has -chen and -lein, so the

southern forms given here may be seen as colloquial.

Diminutives are very much more common in the South

than the North.

368 Variation in German

Austrian German

One of the most widely discussed lexical divides

in standard German is that between Austrian and

German varieties. Items concerned are, of course,

words referring to the different political and administrative systems in the two states, such as Austrian

Matura, contrasting with German Abitur (schoolleaving examination), but also a number of words

for foodstuffs, such as Austrian Schlagobers, Marille

contrasting with German Schlagsahne, Aprikose

(whipped cream, apricot). It must be stressed that

here we are concerned with variants that occur in all

Austrian varieties of German including the formal

standard language not just in traditional dialect.

Not surprisingly, Austrians tend to regard the differences between Austrian German and the German

of Germany as particularly significant, failing to realize that they are a special case of the more general

North-South divide in German.

Austrian attitudes towards Austrian varieties are

complex; on the one hand, there is an identification

and pride in Austrian German, demonstrated by

Austrias insistence that Austrian food terminology be

used in the EUs dealings with Austria. On the other

hand, there is a strange kind of reluctant acceptance

that varieties of German from Germany may be more

correct Austrians may even be heard referring to their

standard language as a dialect. This stems partly from

1871 when the greater part of the German-speaking

area was divided between two states; one retained its

traditional title of Austria, while the other, the large

new state dominated by Prussia (with its capital

in Berlin) adopted the title of the German Empire,

popularly known as Germany/Deutschland. A view

arose, partly unspoken, that the German Empire

was the repository of authentic Germanness and the

authentic German language, particularly because it

was the larger state and largely German-speaking, in

contrast to the multilingual Austro-Hungarian state.

This view was bolstered by the northern varieties of

standard German that already were popularly seen as

more correct. For a comprehensive account of the

differences between the major national and regional

varieties of German and of their social and political

correlates, see Ammon (1995).

Swiss German

The ownership of standard German by the German

state has produced the reaction in contemporary

Switzerland that all standard German is in some

sense foreign to Switzerland. There is a Swiss

standard German particularly characterized like

Austrian standard German (and the standard German

of Germany) by distinctive lexicon and recognized

as Swiss by Germans and Austrians, but the Germanspeaking Swiss are increasingly using it only to communicate with non-Swiss German-speakers or in

the most formal contexts. They are using Swiss

dialects, known as Swiss German/Schweizerdeutsch/

Schwyzertu u tsch, in almost all other spoken communication. This state of affairs could suggest that the

Swiss dialects now represent a separate language from

German, but this is not quite the case; Swiss German

does not have any generally accepted standard variety

and it is relatively rarely used in writing. Some of the

most salient distinctive lexicon of Swiss German consists of items of French origin, such as Chauffeur

(driver), or items referring to specifically Swiss social

and political institutions, like Bundesrat (Swiss Federal

government not to be confused with the Bundesrat in

Germany, the upper house of parliament).

East and West German

During the 40-year division of Germany, particularly

because contact between the citizens of the two states

was restricted, all varieties of the language, including

standard varieties, diverged in the Federal Republic

(west) and the German Democratic Republic (GDR)

(east). Given the important role of language in the

German national identity, this divergence became a

highly charged political issue, with attitudes ranging

from outrage on the part of some conservative West

Germans at perceived Communist efforts to destroy

national unity, to the vision in some GDR circles of

language renewal paralleling social renewal in the

East. A balanced view would perhaps see changes in

both East and West reflecting change and divergence

on both sides. The most obvious differences did indeed reflect different experiences of life in the two

republics with, for example, an entire political and

social vocabulary for East German institutions, such

as Volkskammer (GDR Parliament), Polytechnische

Oberschule (comprehensive School), and Objekt

(building) but also some perhaps unexpected everyday items, such as Kaffee komplett (coffee with milk

and sugar).

As the unification of 1990 was in effect an absorption of the population and territory of the GDR into

the Federal Republic, it might have been expected

that differences in language would steadily be eliminated. Many GDR-specific terms, particularly political and economic terms, have indeed disappeared or

are obsolescent, but there have been some surprising

survivals. Many of these represent salient GDR terms,

which are used to stress continuing East German

Variation in German 369

identity on the part of the many for whom unification

has been more or less a disappointment; an example

here would be Broiler, for Western Bratha hnchen

(roast chicken). On occasion, East Germans seem

simply unaware that they are using GDR-specific

language; I have heard Objekt (public building) and

Kaffee komplett (coffee with milk and sugar) used

unselfconsciously in this way. For a comprehensive

account of the linguistic differences between East and

West past and present set against the political

background, see Stevenson (2003).

Conclusion

As discussed, there is public concern about variability in the standard language, and this is currently

perceived as an increasing problem. Of particular

current concern is the perceived divide between traditional or authentic German and the new variety

corrupted by English influence. As I have argued

elsewhere, though perhaps partly justified in certain

respects, this concern is plagued by misconceptions

about language change and comprehensibility (see

Barbour, 2001).

The new concern about variability in the standard

language may be arising not from any change in the

substance of the language, but from increasing use,

in formal contexts, of words and constructions previously thought of as informal. In linguistic terms,

a new standard language may be arising, creating

from the formal standard (Standardsprache) and the

colloquial standard (varieties of Umgangssprache) a

new type of multi-register standard variety such as

that found in English. Concern about variability in

the standard language is attested to in the papers in

Eichinger (2005).

It is often said that German dialects are being

used less, thus making the language more uniform,

but increasing variability in the standard language

may be compensating for this, ensuring that German

continues to show high salient patterns of variation.

See also: Austria: Language Situation; Dialect Atlases;

Dialect Chains; Dialect Representations in Texts;

German; Germany: Language Situation; Language and

Dialect: Linguistic Varieties; Language Education

Policy in Europe; Language Families and Linguistic

Diversity; Language/Dialect Contact; Luxembourg:

Language Situation; Mother Tongue Education:

Nonstandard Language; Mother Tongue Education:

Standard Language; Prestige, Overt and Covert;

Sociophonetics; Speech Community; Standard and

Dialect Vocabulary; Standardization; Switzerland:

Language Situation; Vernacular.

Bibliography

Ammon U (1995). Die deutsche Sprache in Deutschland,

sterreich und der Schweiz. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

O

Barbour S (1999). Dialects and languages revisited.

The relevance of translation studies to sociolinguistics.

In Kelly-Holmes H & Go rner R (eds.) Vermittlungen.

German studies at the turn of the century. Festschrift

for Nigel B. R. Reeves. Munich: Iudicium. 131150.

Barbour S (2000a). Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxembourg: the total coincidence of nations and speech

communities? In Barbour S & Carmichael C (eds.)

Language and nationalism in Europe. Oxford: Oxford

University Press. 1843.

Barbour S (2000b). Sociolinguistics in the GDR: the study

of language and society in East Germany. In Jackman G

& Roe I (eds.) Finding a voice: problems of language in

East German society and culture (German Monitor, 4).

Amsterdam: Rodopi. 115127.

Barbour S (2001). Defending languages and defending

nations: some perspectives on the use of foreign

words in German. In Davies M C, Flood J L &

Yeandle D N (eds.) Proper words in proper places.

Studies in lexicology and lexicography in honour of

William Jervis Jones. Stuttgart: Heinz. 361374.

Barbour S & Stevenson P (1990). Variation in German.

A critical approach to German sociolinguistics.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barbour S & Stevenson P (1998). Variation im Deutschen.

Soziolinguistische Perspektiven. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Clyne M (1995). The German language in a changing

Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eichhoff J (1977). Wortatlas der deutschen Umgangssprachen (vol. 1). Berne/Munich: Francke.

Eichhoff J (1978). Wortatlas der deutschen Umgangssprachen, (vol. 2). Berne/Munich: Francke.

Eichinger L & Kallmeyer W (2005). Standardvariation:

Wie viel Variation vertragt die Deutsche Sprache? Institut

fu r Deutsche Sprache Jahrbuch 2005. Berlin/New York:

de Gruyter.

Ko nig W (1978). dtv-Atlas zur deutschen Sprache. Munich:

Deuscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

Newton G (1989). Central Franconian. In Russ C V J (ed.)

The dialects of modern German. A linguistic survey.

London/Stanford: Routledge/Stanford University Press.

136209.

Russ C V J (ed.) (1989). The dialects of modern German.

A linguistic survey. London/Stanford: Routledge/Stanford

University Press.

Schlobinski P (1987). Stadtsprache Berlin. Eine soziolinguistische Untersuchung. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Stellmacher D (1997). Sprachsituatuion in Norddeutschland. In Stickel G (ed.) Varieta ten des Deutschen.

Insititut fu r Deutsche Sprache Jahrbuch 1996. Berlin/

New York: de Gruyter. 88108.

Stevenson P (2003). Language and German disunity.

A sociolinguistic history of East and West in Germany,

19452000. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

You might also like

- Typinator TutorialDocument3 pagesTypinator TutorialCambera0% (1)

- The Great Year in Greek, Persian and Hindu AstronomyDocument25 pagesThe Great Year in Greek, Persian and Hindu AstronomyNandini1008No ratings yet

- Kenneth Hale, A Man Who Mastered Many LanguagesDocument9 pagesKenneth Hale, A Man Who Mastered Many LanguagesNur Hanani100% (1)

- Globalization and The Future of GermanDocument387 pagesGlobalization and The Future of GermanAcción Plurilingüe Villa MaríaNo ratings yet

- CognatesDocument236 pagesCognatesmengelito almonteNo ratings yet

- Nones LanguageDocument1 pageNones Languagecrbrunelli100% (1)

- The Role of Prior Knowledge in L3 LearningDocument25 pagesThe Role of Prior Knowledge in L3 LearningKarolina MieszkowskaNo ratings yet

- Culture Bumps LeppihalmeDocument4 pagesCulture Bumps LeppihalmeCarla Luján Di BiaseNo ratings yet

- Upanisads The Worlds Classics by Patrick OlivelleDocument4 pagesUpanisads The Worlds Classics by Patrick OlivelleNandini1008No ratings yet

- Variation in German by S BarbourDocument8 pagesVariation in German by S BarbourNandini1008No ratings yet

- To Be or Not To Be That Is The Question Yhwh and Ea-Anne Marie KitzDocument25 pagesTo Be or Not To Be That Is The Question Yhwh and Ea-Anne Marie KitzHoang Nguyen1982No ratings yet

- A Grammar of Gulf ArabicDocument144 pagesA Grammar of Gulf ArabicNati Man100% (5)

- 25.a Comprehensive Indonesian-English DictionaryDocument1,125 pages25.a Comprehensive Indonesian-English DictionaryEko Tj100% (8)

- (Francis T. Gignac) A Grammar of The Greek Papyri PDFDocument372 pages(Francis T. Gignac) A Grammar of The Greek Papyri PDFLeleScieri100% (3)

- Dutch LanguageDocument25 pagesDutch LanguageAndrei ZvoNo ratings yet

- French IIIDocument17 pagesFrench IIIakshatar20No ratings yet

- The Multilingual LexiconDocument219 pagesThe Multilingual LexiconsakunikaNo ratings yet

- English / German Cognates: Words R Us Bilingual Dictionaries, #41From EverandEnglish / German Cognates: Words R Us Bilingual Dictionaries, #41No ratings yet

- French Accents List: The 5 French Accent MarksDocument7 pagesFrench Accents List: The 5 French Accent MarksmuskaanNo ratings yet

- Cultural and ethical challenges in Tagore's translation of GitanjaliDocument6 pagesCultural and ethical challenges in Tagore's translation of GitanjaliArpan DasNo ratings yet

- Dutch Tutorial SampleDocument10 pagesDutch Tutorial SampleJorotxcamNo ratings yet

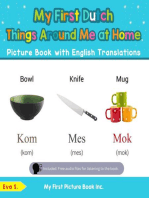

- My First Dutch Things Around Me at Home Picture Book with English Translations: Teach & Learn Basic Dutch words for Children, #13From EverandMy First Dutch Things Around Me at Home Picture Book with English Translations: Teach & Learn Basic Dutch words for Children, #13No ratings yet

- Corpora, Language, Teaching, and Resources: From Theory To PracticeDocument21 pagesCorpora, Language, Teaching, and Resources: From Theory To PracticePepe Castro ErreNo ratings yet

- Learn the German AlphabetDocument7 pagesLearn the German AlphabetadéjeunerNo ratings yet

- 5 Steps To Speak A New LanguageDocument110 pages5 Steps To Speak A New LanguageLe Quoc KhanhNo ratings yet

- VII CBSE Worksheet KEYDocument53 pagesVII CBSE Worksheet KEYGurucharan SaranathNo ratings yet

- How to Approach Learning a New LanguageDocument8 pagesHow to Approach Learning a New Languagejuanleon00No ratings yet

- Balg, Braune. A Gothic Grammar With Selections For Reading and A Glossary. 1895.Document252 pagesBalg, Braune. A Gothic Grammar With Selections For Reading and A Glossary. 1895.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Jean Pruvost The French Language A Long HistoryDocument26 pagesJean Pruvost The French Language A Long HistorySviatoslav ChumakovNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of English WordbuildingDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of English WordbuildingAdib Jasni KharismaNo ratings yet

- Phonological Analysis of LoanwordsDocument15 pagesPhonological Analysis of LoanwordsMaha Mahmoud TahaNo ratings yet

- 2,000 Most Common Polish Words - PolishDocument56 pages2,000 Most Common Polish Words - PolishEstebanNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary: Challenges and Debates: English Language Teaching August 2010Document7 pagesVocabulary: Challenges and Debates: English Language Teaching August 2010Rizky WuNo ratings yet

- Esperanto Grammar (Kellerman) PDFDocument239 pagesEsperanto Grammar (Kellerman) PDFMiguel Angel GayaNo ratings yet

- Guide To Learning Languages DiscussionDocument85 pagesGuide To Learning Languages DiscussionNathaniel MuncieNo ratings yet

- Dictionary of German Slang and Colloquial Expressions by Henry Strutz PDFDocument4 pagesDictionary of German Slang and Colloquial Expressions by Henry Strutz PDFPaula Galiano GutierrezNo ratings yet

- SelftaughtnorwegDocument174 pagesSelftaughtnorwegGyuris AntalNo ratings yet

- German 0Document202 pagesGerman 0Madhu MidhaNo ratings yet

- Frankfurt The Importance of What We Care About PDFDocument16 pagesFrankfurt The Importance of What We Care About PDFJack SidnellNo ratings yet

- German PDFDocument545 pagesGerman PDFsalma_waheedNo ratings yet

- Kurylowicz - On The Development of The Greek IntonationDocument12 pagesKurylowicz - On The Development of The Greek IntonationdharmavidNo ratings yet

- A Martian Sends A Postcard Home WorksheetDocument230 pagesA Martian Sends A Postcard Home WorksheetRogers SureNo ratings yet

- Learn Any Language Progress Without Stress How To Find The Time, Energy and Resources To Master Your Target Language Tried... (Joan Pattison)Document73 pagesLearn Any Language Progress Without Stress How To Find The Time, Energy and Resources To Master Your Target Language Tried... (Joan Pattison)viszkoktundeNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesDaily Lesson PlanAmina U SagabayNo ratings yet

- (Expression of Cognitive Categories, 5) Manfred Krifka - Renate Musan - The Expression of Information Structure-Mouton de Gruyter (2012) PDFDocument476 pages(Expression of Cognitive Categories, 5) Manfred Krifka - Renate Musan - The Expression of Information Structure-Mouton de Gruyter (2012) PDFhafanetti0% (1)

- Sylvia Pankhurst Delphos 1927 PDFDocument120 pagesSylvia Pankhurst Delphos 1927 PDFFrancisco MurciaNo ratings yet

- Unlocking German Your Key To Language Success (Noble, Paul)Document255 pagesUnlocking German Your Key To Language Success (Noble, Paul)vafaxo4985No ratings yet

- Latin (English)Document19 pagesLatin (English)César Cortés GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- MT Japanese IntroductoryDocument13 pagesMT Japanese IntroductoryNiko MarikewNo ratings yet

- The Theory of German Word Order Aldo Scaglione FinereaderDocument185 pagesThe Theory of German Word Order Aldo Scaglione FinereaderCristiano ValoisNo ratings yet

- KHAYYAM Into French PDFDocument6 pagesKHAYYAM Into French PDFefevianNo ratings yet

- Blackwell Reference GrammarsDocument1 pageBlackwell Reference Grammarssatharheart0% (1)

- Linguistic Features of Pun ClassificationDocument5 pagesLinguistic Features of Pun ClassificationRodrigo SouzaNo ratings yet

- Reference Grammar MainDocument60 pagesReference Grammar MainPoojaThakkarNo ratings yet

- German - How To Speak and Write ItDocument388 pagesGerman - How To Speak and Write Itlucas alves100% (1)

- The Legend of Longinus in Ecclesiastical Tradition and in English Literature and Its Connections With The Grail (Rose Peebles) PDFDocument7 pagesThe Legend of Longinus in Ecclesiastical Tradition and in English Literature and Its Connections With The Grail (Rose Peebles) PDFisabel margarita jordánNo ratings yet

- (Teach Yourself Books) H. Koolhoven - Teach Yourself Dutch - A Complete Course For Beginners-NTC Publishing Group (1992)Document228 pages(Teach Yourself Books) H. Koolhoven - Teach Yourself Dutch - A Complete Course For Beginners-NTC Publishing Group (1992)Mook ThanyaNo ratings yet

- Major New Edition German-English Dictionary 3,000+ WordsDocument1 pageMajor New Edition German-English Dictionary 3,000+ Wordsabhaymvyas1144100% (1)

- (Routledge Comprehensive Grammars) Tinatin Bolkvadze, Dodona Kiziria - Georgian - A Comprehensive Grammar-Routledge (2023) (Z-Lib - Io)Document547 pages(Routledge Comprehensive Grammars) Tinatin Bolkvadze, Dodona Kiziria - Georgian - A Comprehensive Grammar-Routledge (2023) (Z-Lib - Io)Ꝟɩɕƭơɾ ƤʃɛɩffɛɾNo ratings yet

- GRAMATICA DL LADIN STANDARDDocument144 pagesGRAMATICA DL LADIN STANDARDkernowsebNo ratings yet

- Mark Durie, Malcolm Ross The Comparative Method Reviewed - Regularity and Irregularity in Language ChangeDocument330 pagesMark Durie, Malcolm Ross The Comparative Method Reviewed - Regularity and Irregularity in Language ChangeAidil FitriawanNo ratings yet

- Wright Comparative Grammar of The Greek LanguageDocument406 pagesWright Comparative Grammar of The Greek Languagerabiaqiba100% (1)

- 5 Techniques To Speak Any Language - Sid Efromovich - TedxuppereastsideDocument4 pages5 Techniques To Speak Any Language - Sid Efromovich - Tedxuppereastsideanna afNo ratings yet

- TaalthuisDocument111 pagesTaalthuisLaura VerheijkeNo ratings yet

- Theory of SuperstitionDocument17 pagesTheory of SuperstitionNandini1008No ratings yet

- The Mythology of The Face Lift by WENDY DONIGERDocument28 pagesThe Mythology of The Face Lift by WENDY DONIGERNandini1008No ratings yet

- Ancient Greek Views on Women's Leadership and Matriarchal SocietiesDocument36 pagesAncient Greek Views on Women's Leadership and Matriarchal SocietiesNandini1008No ratings yet

- William Dwight Whitney and Ernest Renan The Role of Orientalism in Franco-AmericanRelations by Max I. BaymDocument11 pagesWilliam Dwight Whitney and Ernest Renan The Role of Orientalism in Franco-AmericanRelations by Max I. BaymNandini1008No ratings yet

- The Mythology of Masquerading Animals or Bestiality by WENDY DONIGERDocument23 pagesThe Mythology of Masquerading Animals or Bestiality by WENDY DONIGERNandini1008No ratings yet

- Ducks Rabbits and Normal Science Recasting The Kuhns-Eye View of Poppers Demarcation of ScienceDocument21 pagesDucks Rabbits and Normal Science Recasting The Kuhns-Eye View of Poppers Demarcation of ScienceNandini1008No ratings yet

- Philosophy of Science and AstrologyDocument21 pagesPhilosophy of Science and AstrologyNandini1008No ratings yet

- Is Kuhn A SociologistDocument11 pagesIs Kuhn A SociologistNandini1008No ratings yet

- Review of The Bedtrick by Wendy DonigerDocument3 pagesReview of The Bedtrick by Wendy DonigerNandini1008No ratings yet

- When A Kiss Is Still A Kiss Memories of The Mind and The Body in Ancient India and Hollywood by Wendy DonigerDocument10 pagesWhen A Kiss Is Still A Kiss Memories of The Mind and The Body in Ancient India and Hollywood by Wendy DonigerNandini1008No ratings yet

- The Language and Style of The Vedic Rsis by Tatyana J. Elizarenkova and Wendy DonigerDocument3 pagesThe Language and Style of The Vedic Rsis by Tatyana J. Elizarenkova and Wendy DonigerNandini1008No ratings yet

- Why Should A Priest Tell You Whom To Marry A Deconstruction of The Laws of Manu by Wendy DonigerDocument15 pagesWhy Should A Priest Tell You Whom To Marry A Deconstruction of The Laws of Manu by Wendy DonigerNandini1008No ratings yet

- Wendy Doniger The Woman Who Pretended To Be Who She Was Myths of Self ImitationDocument3 pagesWendy Doniger The Woman Who Pretended To Be Who She Was Myths of Self ImitationNandini1008No ratings yet

- The Symbolism of Black and White Babies in Parental Impression MythsDocument45 pagesThe Symbolism of Black and White Babies in Parental Impression MythsNandini1008No ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press The Classical AssociationDocument3 pagesCambridge University Press The Classical AssociationNandini1008No ratings yet

- A Note On The Delphic PriesthoodDocument5 pagesA Note On The Delphic PriesthoodNandini1008No ratings yet

- The Oldest Deception: Review of Wendy Doniger's "The BedtrickDocument2 pagesThe Oldest Deception: Review of Wendy Doniger's "The BedtrickNandini1008No ratings yet

- Variation in Child Language by J L RobertsDocument7 pagesVariation in Child Language by J L RobertsNandini1008No ratings yet

- Theological Foundations of Keplers Astronomy - Peter Barker and Bernard R GoldsteinDocument26 pagesTheological Foundations of Keplers Astronomy - Peter Barker and Bernard R GoldsteinNandini1008100% (1)

- The Stone Breaker by Nirala and Romila ThaparDocument3 pagesThe Stone Breaker by Nirala and Romila ThaparNandini1008No ratings yet

- The Status of Women in The Epics by Shakambari JayalDocument1 pageThe Status of Women in The Epics by Shakambari JayalNandini1008No ratings yet

- Variation in Native Languages of North America by S TrechterDocument8 pagesVariation in Native Languages of North America by S TrechterNandini1008No ratings yet

- Variation in French by J AugerDocument8 pagesVariation in French by J AugerNandini1008No ratings yet

- Interpreting Early India by Romila ThaparDocument2 pagesInterpreting Early India by Romila ThaparNandini1008No ratings yet

- Hipparchus Treatment of Early Greek Astronomy The Case of Eudoxus and The Length of Daytime - Alan C Bowen and Bernard R GoldsteinDocument22 pagesHipparchus Treatment of Early Greek Astronomy The Case of Eudoxus and The Length of Daytime - Alan C Bowen and Bernard R GoldsteinNandini1008No ratings yet

- How We Read Cuneiform Texts - Erica ReinerDocument57 pagesHow We Read Cuneiform Texts - Erica ReinerNandini1008No ratings yet

- Greek Astronomical Calendars III. The Calendar of Dionysios by B. L. Van Der WaerdenDocument7 pagesGreek Astronomical Calendars III. The Calendar of Dionysios by B. L. Van Der WaerdenNandini1008No ratings yet

- Tamil Solutions PDFDocument3 pagesTamil Solutions PDFManendra ShathaNo ratings yet

- Slide PhonologyDocument68 pagesSlide PhonologyBritton DavisNo ratings yet

- Dosuna - 2012 - Ancient Macedonian As A Greek Dialect - A Critical Survey On Recent WorkDocument13 pagesDosuna - 2012 - Ancient Macedonian As A Greek Dialect - A Critical Survey On Recent WorkMakedonas AkritasNo ratings yet

- Test: 2 - Sounds of Language: Phonetics and Phonology: Home Sitemap About ContactDocument73 pagesTest: 2 - Sounds of Language: Phonetics and Phonology: Home Sitemap About ContactAisyah SitiNo ratings yet

- Indian English - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument14 pagesIndian English - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaRaphael T. SprengerNo ratings yet

- Phonological Processes, Lass 1984Document17 pagesPhonological Processes, Lass 1984Estefanía DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Opsl10 PDFDocument184 pagesOpsl10 PDFFrancisco José Da SilvaNo ratings yet

- A Phonological Reconstruction of Proto-ChinDocument191 pagesA Phonological Reconstruction of Proto-ChinHming Lem100% (1)

- Sonorant by Anmar Ahmed English Sonorant ChartDocument9 pagesSonorant by Anmar Ahmed English Sonorant Chartanmar ahmedNo ratings yet

- Problems in Speaking English for Grade 7 StudentsDocument23 pagesProblems in Speaking English for Grade 7 StudentsLauriz EsquivelNo ratings yet

- SyllableDocument14 pagesSyllableega armeliaNo ratings yet

- The Lexical Semantics of The Arabic VerbDocument216 pagesThe Lexical Semantics of The Arabic VerbAhmad Al-Halabi100% (1)

- UNIT 1 - PhoneticsDocument21 pagesUNIT 1 - PhoneticsBui Thanh KhoaNo ratings yet

- Phonetics exercises KEYDocument7 pagesPhonetics exercises KEYMhwaqxLhadyblueNo ratings yet

- GTEDAELV1PIDocument246 pagesGTEDAELV1PISántha SáraNo ratings yet

- Vancova Phonetics and Phonology 2016 PDFDocument99 pagesVancova Phonetics and Phonology 2016 PDFmaruk26No ratings yet

- Tagalog Phonology Paper PDFDocument7 pagesTagalog Phonology Paper PDFRegge GalacNo ratings yet

- Phonetics and Pronounciation PDFDocument184 pagesPhonetics and Pronounciation PDFDimitri Prahesti100% (1)

- Advanced TEFLDocument240 pagesAdvanced TEFLMustafa Elazazy90% (10)

- Sound Symbolism in 00 CiccDocument302 pagesSound Symbolism in 00 CiccbudisanNo ratings yet

- Myanmar AWN PDFDocument15 pagesMyanmar AWN PDFAung NaingNo ratings yet

- Phonology HW answers and exercisesDocument17 pagesPhonology HW answers and exercisesLee Wai KeatNo ratings yet

- English Phonetics and Phonology English Consonants - ExercisesDocument2 pagesEnglish Phonetics and Phonology English Consonants - ExercisesPavelNo ratings yet

- 5 Features of Connected SpeechDocument7 pages5 Features of Connected SpeechLovely Deins AguilarNo ratings yet

- 0715 CB 035Document74 pages0715 CB 035RAyn FrAqaNo ratings yet

- PharyngealizationDocument3 pagesPharyngealizationJuan Carlos Moreno HenaoNo ratings yet