Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lecanomancy

Uploaded by

vivekpatelbii0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

147 views1 pagefuture prediction by spreading oil in water

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentfuture prediction by spreading oil in water

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

147 views1 pageLecanomancy

Uploaded by

vivekpatelbiifuture prediction by spreading oil in water

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

Babylonian Lecanomancy: An Ancient Text on the

Spreading of Oil on Water

D. TABOR

Physics and Chemistry o f Solids, Cavendish Laboratory, Madingley Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom

R e c e i v e d A u g u s t 30, 1979; a c c e p t e d O c t o b e r 16, 1979

I am very glad to add my tribute in this

Festschrift to the work of Professor Zettlemoyer. He has long been engaged in the

study of adsorption on surfaces and is particularly well known for his investigations of

the wetting properties of various (rather

messy) liquids. It seems, therefore, not inappropriate to describe here the earliest

written record of the spreading of oil on

water. It is fairly well known to scholars of

antiquity but not, I believe, to scientists or

even to historians of science (see, however,

the Note added in proof).

BACKGROUND

Between the Tigris and Euphrates lies a

fertile area known to orientalists as Babylonia and Assyria so named after the two main

capital cities, Babylon in the South (Babylonia) and Ashur in the North (Assyria). The

Greeks, who had a word for most things,

called it Mesopotamia (meso = between,

potamos = river). It retained this name

throughout the western world until the end

of World War I when it acquired its present

name, Iraq.

One of the earliest civilizations of which

we have records was that of the Sumerians

who flourished in Southern Mesopotamia

around 3200 B.C. They are credited with

having invented the oldest known written

language. They wrote in clay with a suitable

stylus and if a permanent record was

required the clay could be baked and the

inscriptions so preserved. The writing

apparently began in a pictorial form and

gradually developed into stylized form consisting of linear incisions made with a wedgeshaped stylus. In this form it is known as

cuneiform (Latin cuneus -- wedge).

Sumerian has no known connections with

other linguistic sources. Many of the basic

words were monosyllabic: as a result a

"sign" could serve both as a word and as a

syllable. In this way longer words or words

for which specific signs did not exist could

be spelled out in terms of existing syllabic

signs.

Around 2000 B.C. Sumer was overrun

and gradually dominated by the Akkadians

who brought with them their spoken,

Semitic language but no form of writing.

They therefore adopted and adapted the

Sumerian cuneiform to suit their own needs.

In some cases an "ideogram" might be

adopted to mean the same thing as in

Sumerian although it would be pronounced

as an Akkadian word. This resembles the

use, in Japanese, of Chinese characters; the

character has the same meaning in both

languages but is usually pronounced differently in both. In syllabic writing they took

over the sound (or "value") of the Sumerian

signs and combined these phonetically to

produce the sound of the required Akkadian

word.

One of the most famous Akkadian rulers

was Hammurabi. He is known to orientalists

for his Code (1758 B.C.) which deals largely

with the laws of property and of damages.

240

0021-9797/80/050240-06502.00/0

Copyright 1980by Academic Press, Inc.

All fights of reproduction in any form reserved.

Journal of Colloidand InterfaceScience, Vol. 75, No. 1, May 1980

You might also like

- Civil Procedure Code & Limitation Law Ebook & Lecture Notes PDF Download (Studynama - Com - India's Biggest Website For Law Study Material Downloads)Document119 pagesCivil Procedure Code & Limitation Law Ebook & Lecture Notes PDF Download (Studynama - Com - India's Biggest Website For Law Study Material Downloads)Vinnie Singh100% (5)

- M.B.Parkes - Scribes, Scripts and Readers (Chap.3 Ordinatio and Compilatio)Document22 pagesM.B.Parkes - Scribes, Scripts and Readers (Chap.3 Ordinatio and Compilatio)Rale RatkoNo ratings yet

- Illustrated Dictionary of Word Used in Art and ArcheologyDocument368 pagesIllustrated Dictionary of Word Used in Art and ArcheologyVidhya Raghavan100% (1)

- Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary VOL IDocument760 pagesEgyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary VOL ISamyra Simina100% (4)

- Michalowski Sumerian in Woodard The Cambridge Encyclopedia of The World's Ancient LanguagesDocument41 pagesMichalowski Sumerian in Woodard The Cambridge Encyclopedia of The World's Ancient Languagesruben100% (1)

- Book of Fayum PDFDocument51 pagesBook of Fayum PDFMauricio SchneiderNo ratings yet

- Syesis: Vol. 3, Supplement 1: The Archaeology of the Lochnore-Nesikep Locality, British ColumbiaFrom EverandSyesis: Vol. 3, Supplement 1: The Archaeology of the Lochnore-Nesikep Locality, British ColumbiaNo ratings yet

- The Word Museum: The Most Remarkable English Words Ever ForgottenFrom EverandThe Word Museum: The Most Remarkable English Words Ever ForgottenRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (69)

- Science and Key of Life Vol 2Document259 pagesScience and Key of Life Vol 2cannizzo45091100% (3)

- Detailed English Lesson on Personal ConflictsDocument5 pagesDetailed English Lesson on Personal ConflictsMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Meetisga Book of This Kind, Admitting Its: 8. Eeweeri YDocument2 pagesMeetisga Book of This Kind, Admitting Its: 8. Eeweeri YHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteNo ratings yet

- CuneiformDocument11 pagesCuneiformValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Chaldean Account of Genesis, Oxford 1880 GnosisDocument416 pagesChaldean Account of Genesis, Oxford 1880 GnosisWaterwind100% (1)

- The Aryan Origin of The AlphabetDocument62 pagesThe Aryan Origin of The AlphabetOpenEye100% (1)

- Vergilius, Georgics 1-4 - Papillon, T. L. A. (Texto y Comentario)Document224 pagesVergilius, Georgics 1-4 - Papillon, T. L. A. (Texto y Comentario)Patroclo M.No ratings yet

- 368e904d-7049-4d83-a71e-6d355d166a3eDocument760 pages368e904d-7049-4d83-a71e-6d355d166a3eBranko NikolicNo ratings yet

- ChanceDocument5 pagesChanceJNo ratings yet

- On The Terms Kyma Revta ReversaDocument8 pagesOn The Terms Kyma Revta ReversafevzisNo ratings yet

- Sumerian and Akkadian in Sumer and AkkadDocument9 pagesSumerian and Akkadian in Sumer and AkkadlayevskatNo ratings yet

- Ancientships 00 TorruoftDocument166 pagesAncientships 00 Torruoftmdreadinc2100% (1)

- Chronicleofjoshu00josh 0 PDFDocument234 pagesChronicleofjoshu00josh 0 PDFMurat SaygılıNo ratings yet

- Records of The Past, 2nd Series - 1505Document150 pagesRecords of The Past, 2nd Series - 1505Michael James QuinnNo ratings yet

- Alexander Souter - A Glossary of Later Latin To 600 A.d.-Oxford University Press (1949)Document496 pagesAlexander Souter - A Glossary of Later Latin To 600 A.d.-Oxford University Press (1949)charlie hinkleNo ratings yet

- The Aryan Origin of the Alphabet - Disclosing the Sumero-Phoenician Parentage of Our Letters Ancient and ModernFrom EverandThe Aryan Origin of the Alphabet - Disclosing the Sumero-Phoenician Parentage of Our Letters Ancient and ModernNo ratings yet

- The Chaldean Account of Genesis, ByGeorge Smith and A. HDocument295 pagesThe Chaldean Account of Genesis, ByGeorge Smith and A. HSaud M. H. Sigalingging100% (1)

- Waddell Aryan Origin of AlphabetDocument63 pagesWaddell Aryan Origin of AlphabetSevan Bomar100% (4)

- Easy Lessons in Egyptian HieroglyphicsFrom EverandEasy Lessons in Egyptian HieroglyphicsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Book of The Zodiac by The Diagram Group PDFDocument114 pagesThe Book of The Zodiac by The Diagram Group PDFnjhbsasaa0% (1)

- The Beginnings of Sumerology IDocument15 pagesThe Beginnings of Sumerology Iruben100% (2)

- Cuneiform Writing Techniques - Jan2018-2018-01-29T11 27 42.308291+00 00Document10 pagesCuneiform Writing Techniques - Jan2018-2018-01-29T11 27 42.308291+00 00Romuald DionNo ratings yet

- The Etymology of EdenDocument5 pagesThe Etymology of EdenMarius-Gabriel NiculaeNo ratings yet

- الكلمات الدخيلة في معجم السبئية، بيستون PDFDocument7 pagesالكلمات الدخيلة في معجم السبئية، بيستون PDFgogo1966No ratings yet

- Origin of the Anglo-Saxon Race and Early English SettlementsDocument432 pagesOrigin of the Anglo-Saxon Race and Early English SettlementsJosé Juan Góngora Cortés80% (5)

- De-The Ogams of The Sun TempleDocument33 pagesDe-The Ogams of The Sun Templegrevs0% (1)

- Origin of Anglo SaxonsDocument432 pagesOrigin of Anglo Saxonsnorman_wisdom100% (1)

- Econ5027 9104Document4 pagesEcon5027 9104daffaaNo ratings yet

- Scythia The Interpretation of The Data oDocument13 pagesScythia The Interpretation of The Data oDai ChaoticNo ratings yet

- Chem3337 5554Document4 pagesChem3337 5554Antonette TadleNo ratings yet

- Phys7890 6755Document4 pagesPhys7890 6755Elton OdhiamboNo ratings yet

- Sumerian LanguageDocument5 pagesSumerian LanguageAnonymous CabWGmQwNo ratings yet

- History of Mathematics - Week 2 Module 2Document12 pagesHistory of Mathematics - Week 2 Module 2Lyssa LimNo ratings yet

- An Archaic Dictionary Biographical HistoDocument707 pagesAn Archaic Dictionary Biographical Histofabiano medeirosNo ratings yet

- ПрезентаціяDocument13 pagesПрезентаціяolgagolub044No ratings yet

- The History of Assurbanipal by G. Smith (1871)Document398 pagesThe History of Assurbanipal by G. Smith (1871)Nishra Assyrian OrganisationNo ratings yet

- HISTORY OF LIBRARIES FROM CLAY TO PAPERDocument11 pagesHISTORY OF LIBRARIES FROM CLAY TO PAPERsachin1065No ratings yet

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 14, Slice 6 "Inscriptions" to "Ireland, William Henry"From EverandEncyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 14, Slice 6 "Inscriptions" to "Ireland, William Henry"No ratings yet

- History of Writing PDFDocument9 pagesHistory of Writing PDFblinkNo ratings yet

- Records of The Past 01Document200 pagesRecords of The Past 01Stjepan Palajsa100% (2)

- Musical Times Publications Ltd. The Musical Times and Singing Class CircularDocument4 pagesMusical Times Publications Ltd. The Musical Times and Singing Class CircularKristian JamesNo ratings yet

- Studies in History and Philosophy of Science: Boris DunschDocument14 pagesStudies in History and Philosophy of Science: Boris Dunschbrakim23No ratings yet

- Phys 4570Document4 pagesPhys 4570angel shopNo ratings yet

- Oghams Letters Inscribed in StoneDocument24 pagesOghams Letters Inscribed in StoneMark Bailey100% (8)

- Eng6128 9550Document4 pagesEng6128 9550Test AccountNo ratings yet

- History of Korea V1 - HulbertDocument456 pagesHistory of Korea V1 - Hulbertozzaib100% (1)

- 02 SumerianDocument33 pages02 SumerianlaniNo ratings yet

- Review of 'A History of Foreign Words in English' by Mary S. SerjeantsonDocument3 pagesReview of 'A History of Foreign Words in English' by Mary S. SerjeantsonJoy PascoNo ratings yet

- Spading Up Ancient Words: The Exciting Story of the Archaeology of Words and the AlphabetFrom EverandSpading Up Ancient Words: The Exciting Story of the Archaeology of Words and the AlphabetNo ratings yet

- Short History of Libraries, Printing and Language: Short History Series, #4From EverandShort History of Libraries, Printing and Language: Short History Series, #4No ratings yet

- Rahul's blueprint for successDocument5 pagesRahul's blueprint for successvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- The Art of Prediction-K N RaoDocument10 pagesThe Art of Prediction-K N Raophani_bNo ratings yet

- The Art of Prediction-K N RaoDocument10 pagesThe Art of Prediction-K N Raophani_bNo ratings yet

- Effects of Solar System On Piles (Hemorrhoids) - A Case Study Based On Medical AstrologyDocument5 pagesEffects of Solar System On Piles (Hemorrhoids) - A Case Study Based On Medical AstrologyAnonymous izrFWiQNo ratings yet

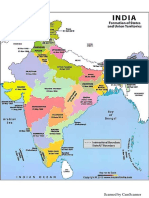

- New Map of IndiaDocument1 pageNew Map of IndiavivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- CRPC - Salient FeaturesDocument42 pagesCRPC - Salient FeaturesRITIKANo ratings yet

- New Map of India PDFDocument1 pageNew Map of India PDFvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Legal Maxims and Phrases 16jan17Document15 pagesLegal Maxims and Phrases 16jan17Bikash KumarNo ratings yet

- Effects of Solar System On Piles (Hemorrhoids) - A Case Study Based On Medical AstrologyDocument5 pagesEffects of Solar System On Piles (Hemorrhoids) - A Case Study Based On Medical AstrologyAnonymous izrFWiQNo ratings yet

- Jaimini Astrology Sthira Dasha With A Case Study PDFDocument6 pagesJaimini Astrology Sthira Dasha With A Case Study PDFAshwani PathakNo ratings yet

- Specific Relief Act 1963-47 PDFDocument17 pagesSpecific Relief Act 1963-47 PDFvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- The Art of Prediction-K N RaoDocument10 pagesThe Art of Prediction-K N Raophani_bNo ratings yet

- Some Correlation Between Onset of Specific Diseases and Indication System in Skin and Lines of Human PalmDocument5 pagesSome Correlation Between Onset of Specific Diseases and Indication System in Skin and Lines of Human PalmvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Grahas (Planets) in Indian AstrologyDocument3 pagesGrahas (Planets) in Indian AstrologyvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Some Correlation Between Onset of Specific Diseases and Indication System in Skin and Lines of Human PalmDocument5 pagesSome Correlation Between Onset of Specific Diseases and Indication System in Skin and Lines of Human PalmvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Specific Relief Act 1963-47 PDFDocument17 pagesSpecific Relief Act 1963-47 PDFvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Medical PalmistryDocument5 pagesMedical PalmistryvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Medical PalmistryDocument5 pagesMedical PalmistryvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Very Important Judgements - All ActsDocument19 pagesVery Important Judgements - All ActsKumar Naveen0% (1)

- 09 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument32 pages09 - Chapter 2 PDFvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Applicationof Ancient Indian Principlesof Architectureand Engineeringin Modern PracticeDocument6 pagesApplicationof Ancient Indian Principlesof Architectureand Engineeringin Modern PracticevivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Computer Awereness 2000 QustnsDocument83 pagesComputer Awereness 2000 QustnsTuhin AzadNo ratings yet

- 1465643597-Specifc Relief Act in Hindi PDFDocument16 pages1465643597-Specifc Relief Act in Hindi PDFvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- Divination SystemsDocument75 pagesDivination SystemsnuthinmuffinNo ratings yet

- MPPSC Prelims 2018 Paper 1 Gshindi PDFDocument15 pagesMPPSC Prelims 2018 Paper 1 Gshindi PDFvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- THE TRANSFER OF PROPERTY ACT 1882Document22 pagesTHE TRANSFER OF PROPERTY ACT 1882charvin100% (1)

- Vaastu and CancerDocument2 pagesVaastu and CancervivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- 7nonf ErosianmythDocument255 pages7nonf ErosianmythvivekpatelbiiNo ratings yet

- AmanKumar (3 0)Document5 pagesAmanKumar (3 0)ShivaprasadNo ratings yet

- Lab Session 3 DescriptionDocument6 pagesLab Session 3 DescriptionUmer huzaifaNo ratings yet

- Western Philosophy - PPT Mar 7Document69 pagesWestern Philosophy - PPT Mar 7Hazel Joy UgatesNo ratings yet

- Japanese VocabularyDocument18 pagesJapanese Vocabulary698m6No ratings yet

- 2 enDocument141 pages2 enNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Traffic Survey ResultsDocument5 pagesTraffic Survey ResultsHorts Jessa100% (2)

- 26 The Participles: 272 The Present (Or Active) ParticipleDocument7 pages26 The Participles: 272 The Present (Or Active) ParticipleCerasela Iuliana PienoiuNo ratings yet

- Pre-Colonial and Rizal's View On NationalismDocument3 pagesPre-Colonial and Rizal's View On NationalismKATHERINE GALDONESNo ratings yet

- Navtex Navtex Navtex Navtex Broadcasting System Broadcasting System Broadcasting System Broadcasting SystemDocument26 pagesNavtex Navtex Navtex Navtex Broadcasting System Broadcasting System Broadcasting System Broadcasting SystemTomis HonorNo ratings yet

- Primero de Secundaria INGLES 1 III BimestreDocument5 pagesPrimero de Secundaria INGLES 1 III BimestreTania Barreto PenadilloNo ratings yet

- HUM02 CO4 - Contemporary FilmDocument5 pagesHUM02 CO4 - Contemporary FilmJade Francis San MiguelNo ratings yet

- Eli K-1 Lesson 1Document6 pagesEli K-1 Lesson 1ENo ratings yet

- Literature Presentation by Yasmine RamosDocument76 pagesLiterature Presentation by Yasmine Ramosenimsay somarNo ratings yet

- PT-E110VP Brochure PDFDocument4 pagesPT-E110VP Brochure PDFJohn GarnetNo ratings yet

- How To Summon GusoinDocument4 pagesHow To Summon Gusoinhery12100% (3)

- Medieval English Literature Explores Romance, Chivalry and Arthurian LegendDocument12 pagesMedieval English Literature Explores Romance, Chivalry and Arthurian LegendDaria VescanNo ratings yet

- Aparokshanubhuti EngDocument33 pagesAparokshanubhuti Engscribsub100% (4)

- Ko 8 Grun Orders Ett CollectDocument12 pagesKo 8 Grun Orders Ett CollectreibeltorresNo ratings yet

- تطبيق أركون للمنهج النقدي في قراءة النص القرآني سورة التوبة أنموذجاDocument25 pagesتطبيق أركون للمنهج النقدي في قراءة النص القرآني سورة التوبة أنموذجاLok NsakNo ratings yet

- SV Datatype Lab ExerciseDocument3 pagesSV Datatype Lab Exerciseabhishek singhNo ratings yet

- Reported SpeechDocument4 pagesReported SpeechKilo MihaiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Sigtran:: A White PaperDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Sigtran:: A White PaperEbo BentilNo ratings yet

- Britannia Hotels Job Interview QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesBritannia Hotels Job Interview QuestionnaireAnonymous jPAGqlNo ratings yet

- Editing Tools in AutocadDocument25 pagesEditing Tools in AutocadStephanie M. BernasNo ratings yet

- en KIX4OTRS SimpleDevelopmentAndAdminDocumentationDocument124 pagesen KIX4OTRS SimpleDevelopmentAndAdminDocumentationLucas SchimitNo ratings yet

- ITD Database Querying and MetadataDocument3 pagesITD Database Querying and MetadatadsadasdasNo ratings yet

- Scripting Components For AutoCAD Plant 3DDocument14 pagesScripting Components For AutoCAD Plant 3DJose TorresNo ratings yet

- Christmas The Readings From The Nine Lessons and CarolsDocument7 pagesChristmas The Readings From The Nine Lessons and CarolsLen SalisburyNo ratings yet