Professional Documents

Culture Documents

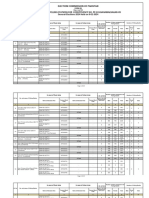

MR1139 Sum

Uploaded by

Adrian Guzman0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views4 pagesinfobiorevolution

Original Title

MR1139.sum

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentinfobiorevolution

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views4 pagesMR1139 Sum

Uploaded by

Adrian Guzmaninfobiorevolution

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

ix

Summary

This report presents the findings of a study group held during 1998 and 1999. A

series of eight meetings explored emerging technologies and the governance

issues they raise for the scientific and policy communities.

Technology and Governance

In the early part of the 21st century, the technologies emerging from the

information technology and biotechnology revolutions will present

unprecedented governance challenges to national and international political

systems. These technologies are now shifting and will continue to affect the

organization of society and the ways in which norms emerge and governance

structures operate. How policymakers respond to the challenges these

technologies present, including the extent to which developments are supported

by public research funds and whether they are regulated, will be of increasing

concern among citizens and for governing bodies. New governance

mechanisms, particularly on an international level, may be needed to address

these emerging issues.

The governance challenges are emerging because of the very nature of these

technologies. Information and biological technologies have in common that their

control and use are largely in the hands of the individual. The technologies that

drove the industrial revolution are systematic and complex, and putting them

into use requires collective action, social infrastructure, and technical know-how.

Information and biological technologies do not have the same large-scale,

systematic naturemaking it harder to control their dissemination and use. The

governance challenge is no longer democratic control over centralized systems

as it was in the 20th century, with such technologies as nuclear weaponry and

energy, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, medicine, and airlinesbut

governance over decentralized, distributed systems. The features that make

these technologies different from and their potential benefits greater than those

of other technologies increase their potential for abuse.

The mechanisms societies use to control, direct, shape, or regulate certain kinds

of activities is what we mean by governance. Governance is almost always

conducted by governmental bodies, although it can be carried out in other ways.

Yet, the practical obstacles to governance of these new technologies are

tremendous. Success in governing them requires the cooperation of

stakeholders, states, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), interest

organizations, and the average citizen. Within any decisionmaking process,

commercial, defense, social, and individual interests will intermingle, and a

consensus among many players may be integral to any workable outcome.

Accordingly, two central questions seem relevant: Is society likely to call for

governance in new technology domains, such as the Internet and biotechnology?

What governance issues do these technologies raise?

Changing Attitudes Toward the Need for Governance

Two recent shifts in attitudes strongly influence the issue of governance within

technological arenas. The first shift is the decline of conventional top-down

governance models and an emphasis on applying privatization; deregulation;

downsizing of bureaucracy; and private, market-based solutions to many social

problems. This trend is especially evident in telecommunications and

information technology (IT). The largely positive and beneficial nature of IT,

coupled with the anti-statist attitudes of the late 20th century, have shifted

attitudes toward technology more generally and disinclined many from

considering regulation as an effective solution to the challenges new technologies

present.

The second shift is a changing public attitude toward the conduct of scientific

research and the resulting technological innovations that might best be summed

up as follows: Dont leave scientific decisionmaking to the scientists. The most

important influence on this perspective may have been our experience with the

advent of nuclear weapons. Many greeted this world-changing technological

development with great alarm, which has led to the creation of an international

regime to prevent the technology from spreading. In the United States, the 1995

Government Performance and Review Act concisely illustrates this trend toward

greater societal interest in knowing the outcomes emerging from the scientific

enterprise. New reporting requirements are being introduced despite continued

protestations from the scientific community that such accountability is not

practical and may even be detrimental to innovation.

These trends suggest that the publics perspective about science and technology

has become increasingly sophisticated. There seems to be general recognition

that regulating new technologies poses substantial challenges and often has

unintended consequences that may be as troublesome to society as the problem

the regulation was intended to prevent. Recognition also appears to be growing

that technological innovation is not always necessarily benign and that some

xi

regulatory actions have served societal objectives effectively. Accommodating

both perspectives raises difficult and complex issues for those who would offer

governance approaches.

Possible Approaches to Governance

A consensus emerged from the study group that a top-down approach to

governance of these technologies would not be practical. In the realm of

standard-setting, a bottom-up, informal approach could prove workable, given

the incentives for participants to converge on a single standard. However,

regulation is more challenging. Enforcement across a wide variety of countries is

likely to present problems, especially when top-down intergovernmental

mechanisms lack force or fail because governments are unwilling to pressure one

another. Moreover, the extent of the control of these technologies and their

applications that is or will be in the hands of the individual makes regulation

particularly difficult. Given that many decisions about use and application will

be made on an individual basis, it is hard to image any regulatory structure

without wide buy-in from the polity.

Accordingly, one approach to regulating technologies like these might be to use a

distributed decisionmaking model that would involve a significant number of

organizations and users in deciding what technologies to support with research

and development funds; what technologies need governance; what the norms of

use and application should be; and whether, how, and at what level of formality

to regulate technologies.

Another possible approach would be using citizen councils to make

recommendations to higher-level, more formal governing bodies. One model

might involve aiding the organization of hundreds of citizen councils across the

United States (or even around the world) and encouraging them to deliberate the

norms of use, regulation, and governance of technology. Using the networking

capacities of information technology, such councils could conceivably deliberate

and share ideas on a series of governance questions in a way that draws toward a

consensus of views on how to manage and govern technologies.

A third model the study group discussed was governance by the actions of

NGOs. In numerous recent examples, NGOs, empowered by low-cost electronic

communications, have been able to act to achieve outcomes that sovereign

nation-states, acting either alone or in concert, could not. However, since NGOs

base their authority primarily on the voluntary choices of their members, this can

raise issues of legitimacy and may be applicable to only a limited range of

problems.

xii

Ultimately, because the technologies emerging from the information and

biological revolutions are inherently global, success in governing these

technologies is likely to depend on some model that involves all stakeholders

states, NGOs, interest organizations, and citizensto cooperate in developing

governance norms or structures.

You might also like

- Isaca Cisa CoursewareDocument223 pagesIsaca Cisa CoursewareAparup Giri100% (1)

- BABOK-v3 Knowledge Areas & Task Summary-MatrixDocument22 pagesBABOK-v3 Knowledge Areas & Task Summary-MatrixJay PatelNo ratings yet

- Excecutive Order No. 1 of 2022 - Organization of The Government of KenyaDocument62 pagesExcecutive Order No. 1 of 2022 - Organization of The Government of KenyaGerald GekaraNo ratings yet

- Legislating Privacy: Technology, Social Values, and Public PolicyFrom EverandLegislating Privacy: Technology, Social Values, and Public PolicyNo ratings yet

- Letter From PrisonDocument10 pagesLetter From PrisonNur Sakinah MustafaNo ratings yet

- SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES AND RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: A Guide For USAID Staff and PartnersDocument160 pagesSUSTAINABLE FISHERIES AND RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: A Guide For USAID Staff and PartnersdutvaNo ratings yet

- Possible Government Actions: Conclusions and RecommendationsDocument5 pagesPossible Government Actions: Conclusions and RecommendationsAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 2016 Book QueueingTheoryAndNetworkApplicDocument21 pages2016 Book QueueingTheoryAndNetworkApplicTolulopeAdesinaNo ratings yet

- E-Governance Models and ICT ComponentsDocument17 pagesE-Governance Models and ICT ComponentsAnkurita PhalwariaNo ratings yet

- The Promise and Challenge of Emerging TechnologiesDocument10 pagesThe Promise and Challenge of Emerging TechnologiesAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- A Three-Stage Adoption Process For Social Media Use in GovernmentDocument12 pagesA Three-Stage Adoption Process For Social Media Use in Governmentmarucha906No ratings yet

- Leitner-Stiefmueller2019 Chapter DisruptiveTechnologiesAndThePuDocument38 pagesLeitner-Stiefmueller2019 Chapter DisruptiveTechnologiesAndThePuLuis Miguel Aznar RubioNo ratings yet

- The Problem of GovernanceDocument11 pagesThe Problem of GovernanceAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- From Private Regulation To Power Politics - The Rise of China in AI Private Governance Through StandardisationDocument28 pagesFrom Private Regulation To Power Politics - The Rise of China in AI Private Governance Through StandardisationFernanda MagalhãesNo ratings yet

- E-Governance Literature Review: ICT's Role in GovernmentDocument6 pagesE-Governance Literature Review: ICT's Role in Governmentalak coolNo ratings yet

- Norms and Values in Digital MediaDocument20 pagesNorms and Values in Digital MediaSignals Telecom ConsultingNo ratings yet

- The Global Spread of The Internet: The Role of International Diffusion Pressures in Technology AdoptionDocument44 pagesThe Global Spread of The Internet: The Role of International Diffusion Pressures in Technology AdoptionArt Cayabyab Ema Jr.No ratings yet

- E-Democracy and Community Networks:: Political Visions, Technological Opportunities, and Social RealityDocument19 pagesE-Democracy and Community Networks:: Political Visions, Technological Opportunities, and Social Realitylmakombe4097No ratings yet

- IT and Environmental Governance in ChinaDocument14 pagesIT and Environmental Governance in ChinaKaterina TsakmakidouNo ratings yet

- Bien BienDocument2 pagesBien Bienconcordiozozobrado028No ratings yet

- Smart Governance: A Roadmap For Research and Practice: Hans J. Scholl and Margit C. SchollDocument14 pagesSmart Governance: A Roadmap For Research and Practice: Hans J. Scholl and Margit C. SchollBrughe BaeNo ratings yet

- ICT Adoption Methods in Developing Countries ResearchDocument42 pagesICT Adoption Methods in Developing Countries ResearchMulugeta TeklebrahanNo ratings yet

- Mi MiDocument10 pagesMi MiMarnie SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Cybernetic GovernanceDocument3 pagesCybernetic Governancesuhajanan16No ratings yet

- Tech Soc ControlDocument8 pagesTech Soc ControlMelani Cristal AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Interact2005.sedam StranaDocument7 pagesInteract2005.sedam StranastentorijaNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Information Technology: Forging New Partnerships in Public AdministrationDocument14 pagesGlobalization and Information Technology: Forging New Partnerships in Public AdministrationGauravNo ratings yet

- Group 5 E-Governance Models BPA 4-2 Broadcasting ModelDocument6 pagesGroup 5 E-Governance Models BPA 4-2 Broadcasting ModelHannah DanielleNo ratings yet

- The Regulation of Technology and The Technology of RegulationDocument18 pagesThe Regulation of Technology and The Technology of RegulationCecilia SelaruNo ratings yet

- Technological Change Modeling and Social ProcessesDocument2 pagesTechnological Change Modeling and Social Processesyav007No ratings yet

- Data SolidarityDocument61 pagesData Solidarity1985poojaNo ratings yet

- Leighton AndrewsDocument15 pagesLeighton AndrewsBrayan A LopezNo ratings yet

- MR1139 Chap1Document1 pageMR1139 Chap1Adrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- CONCLUSION and SUGGESTION Forn Justice Delivery System During PandemicDocument4 pagesCONCLUSION and SUGGESTION Forn Justice Delivery System During PandemicNikhil kumarNo ratings yet

- Tanzania Case Study Rapid Technological ChangeDocument68 pagesTanzania Case Study Rapid Technological ChangeRobert AugustineNo ratings yet

- E-Justice Strategic Use of ICT in Judicial ReformDocument22 pagesE-Justice Strategic Use of ICT in Judicial ReformHarumNo ratings yet

- Globalisation, Free Markets and Public AdministrationDocument26 pagesGlobalisation, Free Markets and Public AdministrationprabodhNo ratings yet

- 3.2.b-Technological ChangeDocument23 pages3.2.b-Technological Changejjamppong09No ratings yet

- Activity 10 IT01 Santos Mark ChristianDocument1 pageActivity 10 IT01 Santos Mark ChristianJulie Ann MalazarteNo ratings yet

- Political economy conversations from the CITIGEN networkDocument8 pagesPolitical economy conversations from the CITIGEN networkIT for ChangeNo ratings yet

- Frontier TechnologiesDocument26 pagesFrontier TechnologiesMugarura CavinNo ratings yet

- MypdfDocument2 pagesMypdfAlecNo ratings yet

- Industrial Relation and Technological ChangeDocument17 pagesIndustrial Relation and Technological Changesjha1187100% (1)

- Developing Government-To-Government EnterpriseDocument20 pagesDeveloping Government-To-Government Enterprisemrabie2004No ratings yet

- Новий Документ Microsoft WordDocument1 pageНовий Документ Microsoft WordMaX RuNNo ratings yet

- Essay The New GovernanceDocument4 pagesEssay The New Governancecahyani putriNo ratings yet

- Introducing A New E-Governance Framework in The Commonwealth: From Theory To PracticeDocument27 pagesIntroducing A New E-Governance Framework in The Commonwealth: From Theory To PracticeMagdiel GuardadoNo ratings yet

- 5. Lecture Digital -Governance.pptxDocument32 pages5. Lecture Digital -Governance.pptxpoonamsingh5874No ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document19 pagesJurnal 2RANIA ABDUL AZIZ BARABANo ratings yet

- Sally Engle Merry - MEASURING THE WORLDDocument13 pagesSally Engle Merry - MEASURING THE WORLDFábio RochaNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document29 pagesPresentation 1maniegojasmineriveraNo ratings yet

- Adm Week 7 - Q4 - UcspDocument5 pagesAdm Week 7 - Q4 - UcspCathleenbeth MorialNo ratings yet

- UHD Conference Paper on ICT Success Factors for Public Sector TransparencyDocument8 pagesUHD Conference Paper on ICT Success Factors for Public Sector TransparencyAlHajDr-SalahideenNo ratings yet

- The Californication' of Government? Crowdsourcing and The Red Tape ChallengeDocument31 pagesThe Californication' of Government? Crowdsourcing and The Red Tape Challenge"150" - Rete socialeNo ratings yet

- Millennial Era-Healthcare Disruption Innovation (Introducing Care 4.0) : Technical NotesDocument8 pagesMillennial Era-Healthcare Disruption Innovation (Introducing Care 4.0) : Technical NotesRosliana MahardhikaNo ratings yet

- E-Government in The Asia-Pacific Region by Clay G. WescottDocument31 pagesE-Government in The Asia-Pacific Region by Clay G. WescottThit SarNo ratings yet

- Document 6Document30 pagesDocument 6Marj VNo ratings yet

- 4BottYoungCrowdsourcing EditadoDocument24 pages4BottYoungCrowdsourcing EditadoluamsmarinsNo ratings yet

- Snellen2003 Chapter E-knowledgeManagementInPublicADocument6 pagesSnellen2003 Chapter E-knowledgeManagementInPublicALorienelNo ratings yet

- Digital GovernansiDocument32 pagesDigital GovernansiAnonymous kpND1j8hNo ratings yet

- E-Goverment Opportunities and ChallengesDocument24 pagesE-Goverment Opportunities and ChallengesMikaye WrightNo ratings yet

- The Aggregate and Complementary Impact of Micro Distortions AutoresDocument35 pagesThe Aggregate and Complementary Impact of Micro Distortions AutoresRodrigo GarayNo ratings yet

- Accelerating Democracy: Transforming Governance Through TechnologyFrom EverandAccelerating Democracy: Transforming Governance Through TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Ec 970 - Session 15 - Exchange RatesDocument11 pagesEc 970 - Session 15 - Exchange RatesAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Ec 970 - Transaction CostsDocument14 pagesEc 970 - Transaction CostsAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Ec 970 - Microeconometrics PDFDocument12 pagesEc 970 - Microeconometrics PDFAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Web Science 2.0: Identifying Trends Through Semantic Social Network AnalysisDocument9 pagesWeb Science 2.0: Identifying Trends Through Semantic Social Network AnalysisAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Ec 970 - Session 20 - Social Choice and Welfare EconomicsDocument17 pagesEc 970 - Session 20 - Social Choice and Welfare EconomicsAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 CH 6Document10 pagesMR517 CH 6Adrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Ec 970 - Session 18 - Phillips CurveDocument22 pagesEc 970 - Session 18 - Phillips CurveAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Updates Since 1994: Growth of Space CommerceDocument7 pagesUpdates Since 1994: Growth of Space CommerceAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Ec 970 - Session 21 - Public Choice and Political EconomyDocument13 pagesEc 970 - Session 21 - Public Choice and Political EconomyAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 TabsDocument1 pageMR517 TabsAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Class Behavioral SlidesDocument39 pagesClass Behavioral SlidesAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Illustrative Military Space Strategy Options in The Post-Cold War WorldDocument20 pagesIllustrative Military Space Strategy Options in The Post-Cold War WorldAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 PrefDocument1 pageMR517 PrefAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 BibDocument6 pagesMR517 BibAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 SumDocument6 pagesMR517 SumAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Moving Ahead: A New Turn of MindDocument5 pagesMoving Ahead: A New Turn of MindAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 CH 1Document3 pagesMR517 CH 1Adrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 AcronymsDocument3 pagesMR517 AcronymsAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 ch3Document26 pagesMR517 ch3Adrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 FiglistDocument1 pageMR517 FiglistAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR1033 FigtabDocument1 pageMR1033 FigtabAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR1033 Chap4Document15 pagesMR1033 Chap4Adrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- The "Proliferation" of Spacepower: A Geopolitical and Policy ContextDocument16 pagesThe "Proliferation" of Spacepower: A Geopolitical and Policy ContextAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR517 AcksDocument2 pagesMR517 AcksAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR1033 PrefDocument1 pageMR1033 PrefAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR1033 SumDocument4 pagesMR1033 SumAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- NoopoliticDocument27 pagesNoopoliticLelly AndriasantiNo ratings yet

- MR1033 Chap1Document6 pagesMR1033 Chap1Adrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MR1033 Chap2Document19 pagesMR1033 Chap2Adrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- DTPM2 Close Program Template v1.0Document19 pagesDTPM2 Close Program Template v1.0Ashish NalavadeNo ratings yet

- UniTP Purple Book - Enhancing University Income Generation, Endowment and Waqf 2Document100 pagesUniTP Purple Book - Enhancing University Income Generation, Endowment and Waqf 2ezat ameerNo ratings yet

- ILP PermitDocument1 pageILP PermitRasikul Hossein SkNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Board of Directors in Corporate GovernanceDocument12 pagesThe Role of The Board of Directors in Corporate GovernancedushyantNo ratings yet

- Brgy. Reso BirDocument2 pagesBrgy. Reso BirCazy Mel EugenioNo ratings yet

- QAMAR - Global Trends in ExtensionDocument16 pagesQAMAR - Global Trends in ExtensionRechil TorregosaNo ratings yet

- Best Team Memorial Petitioner Nalsar BR Sawhney Moot 10 20 21bbl179 Nirmauniacin 20221114 132912 1 10Document10 pagesBest Team Memorial Petitioner Nalsar BR Sawhney Moot 10 20 21bbl179 Nirmauniacin 20221114 132912 1 10rajatNo ratings yet

- ENISA Report - Digital Identity - Leveraging The SSI Concept To Build TrustDocument51 pagesENISA Report - Digital Identity - Leveraging The SSI Concept To Build TrustanlemacoNo ratings yet

- PP 243Document20 pagesPP 243baba razzaiqNo ratings yet

- Joao Catarino ExtendedAbstractDocument10 pagesJoao Catarino ExtendedAbstractALI MAKEENNo ratings yet

- Edp Integrated Report 2022 - Website VersionDocument617 pagesEdp Integrated Report 2022 - Website Versionjoshua.petersenNo ratings yet

- RMIT's International Plan: Global Reach and Outlook 2016 - 2020Document16 pagesRMIT's International Plan: Global Reach and Outlook 2016 - 2020kumar.arasu8717No ratings yet

- 0910 - PIP Project DocumentDocument49 pages0910 - PIP Project DocumentarcnpcNo ratings yet

- Q3 Module 1Document3 pagesQ3 Module 1Alex Abonales DumandanNo ratings yet

- Group ICRA: Credit Rating, Consulting, IT Services & AnalyticsDocument32 pagesGroup ICRA: Credit Rating, Consulting, IT Services & AnalyticsrohitcoolratheeNo ratings yet

- Gopinath Pharma: Nanjibhai B KathiriyaDocument14 pagesGopinath Pharma: Nanjibhai B KathiriyaChintan B BhayaniNo ratings yet

- Senate - 2023 March 20 (r2)Document3 pagesSenate - 2023 March 20 (r2)BernewsAdminNo ratings yet

- Khairahani MunicipalityDocument205 pagesKhairahani Municipalityrashmi bhailaNo ratings yet

- Stuart and Another V National Home Builders Registration Council 89999-2018 2021 ZAGPPHC 171 29 March 2021Document6 pagesStuart and Another V National Home Builders Registration Council 89999-2018 2021 ZAGPPHC 171 29 March 2021BRUCE MACMILLANNo ratings yet

- Structure Plan For Onitsha and Satellite TownsDocument114 pagesStructure Plan For Onitsha and Satellite TownsUnited Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)No ratings yet

- Discussion Forum Assignment Help On Environmental Social GovernanceDocument9 pagesDiscussion Forum Assignment Help On Environmental Social GovernancejennifersmithsahNo ratings yet

- Blockchain TechnologyDocument7 pagesBlockchain TechnologyLinda StewartNo ratings yet

- Information Security Governance - Motivations, Benefits and OutcomesDocument4 pagesInformation Security Governance - Motivations, Benefits and OutcomesEsteban Miranda NavarroNo ratings yet

- Unit-II Codification of Laws-First & Second Law CommissionDocument7 pagesUnit-II Codification of Laws-First & Second Law CommissionUjjwal JainNo ratings yet

- Aide MemoireDocument2 pagesAide MemoireAlthea Janine GomezNo ratings yet