Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Writ of Amparo Case Nos. 1 and 2

Uploaded by

Janus Mari0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 views3 pagesghghghgh

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentghghghgh

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 views3 pagesWrit of Amparo Case Nos. 1 and 2

Uploaded by

Janus Marighghghgh

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

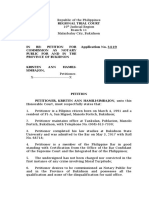

Caram v. Segui, et al GR. No.

193652 August 5, 2014

Facts: Ma. Christina Caram became pregnant with the child of Gicano Constantino III

without the benefit of marriage. Christina mislead Gicano into believing that she

had an abortion when in fact she proceeded to complete the term of her pregnancy.

When she gave birth to Baby Julian, she voluntarily surrendered the baby by way of

Deed of Voluntary Commitment to DSWD. During the wake of Gicano, Christina

confessed to Gicanos family that she had a son and gave him up for adoption due

to financial distress and initial embarrassment. When they decided to recover the

baby, the DSWD, through respondents, refused, arguing that Christina had already

terminated her parental authority over Baby Julian by virtue of the Deed of

Voluntary Committment and that he is already declared legally available for

adoption. Christina filed a petition for the issuance of a Writ of Amparo before the

Quezon RTC, seeking to obtain the custody of Baby Julian from respondents. The

RTC rendered judgement in favor of respondents. Christina then elevated the case

to the SC. She alleged that her enforced separation from Baby Julian amounted to

an enforced disappearance within the context of the Amparo rule.

Issue: whether or not a writ of Amparo is the proper remedy in this case.

Ruling: NO. Section 1 of the Rule on the Writ of Amparo provides as follows:

SECTION 1. Petition. The petition for a writ of Amparo is a remedy available to any

person whose right to life, liberty and security is violated or threatened with

violation by an unlawful actor omission of a public official or employee, or of a

private individual or entity.

The writ shall cover extralegal killings and enforced disappearances or threats

thereof. T]he Amparo Rule was intended to address the intractable problem of

"extralegal killings" and "enforced disappearances," its coverage, in its present

form, is confined to these two instances or to threats thereof. "Extralegal killings"

are "killings committed without due process of law, i.e., without legal safeguards or

judicial proceedings." On the other hand, "enforced disappearances" are "attended

by the following characteristics: an arrest, detention or abduction of a person by a

government official or organized groups or private individuals acting with the direct

or indirect acquiescence of the government; the refusal of the State to disclose the

fate or whereabouts of the person concerned or a refusal to acknowledge the

deprivation of liberty which places such persons outside the protection of law. The

elements constituting enforced disappearances are the following:

(a) that there be an arrest, detention, abduction or any form of deprivation of

liberty;

(b) that it be carried out by, or with the authorization, support or

acquiescence of, the State ora political organization;

(c) that it be followed by the State or political organizations refusal to

acknowledge or give information on the fate or whereabouts of the person

subject of the Amparo petition; and,

(d) that the intention for such refusal is to remove subject person from the

protection of the law for a prolonged period of time.

In this case, Christina alleged that the respondent DSWD officers caused her

"enforced separation" from Baby Julian and that their action amounted to an

"enforced disappearance" within the context of the Amparo rule. Contrary to her

position, however, the respondent DSWD officers never concealed Baby Julian's

whereabouts. In fact, Christina obtained a copy of the DSWD's May 28, 2010

Memorandum explicitly stating that Baby Julian was in the custody of the Medina

Spouses when she filed her petition before the RTC. Besides, she even admitted in

her petition for review on certiorari that the respondent DSWD officers presented

Baby Julian before the RTC during the hearing held in the afternoon of August 5,

2010. There is therefore, no "enforced disappearance" as used in the context of the

Amparo rule as the third and fourth elements are missing.

Christina's directly accusing the respondents of forcibly separating her from her

child and placing the latter up for adoption, supposedly without complying with the

necessary legal requisites to qualify the child for adoption, clearly indicates that she

is not searching for a lost child but asserting her parental authority over the child

and contesting custody over him. Since it is extant from the pleadings filed that

what is involved is the issue of child custody and the exercise of parental rights over

a child, who, for all intents and purposes, has been legally considered a ward of the

State, the Amparo rule cannot be properly applied.

To reiterate, the privilege of the writ of Amparo is a remedy available to victims of

extra-judicial killings and enforced disappearances or threats of a similar nature,

regardless of whether the perpetrator of the unlawful act or omission is a public

official or employee or a private individual. It is envisioned basically to protect and

guarantee the right to life, liberty and security of persons, free from fears and

threats that vitiate the quality of life.

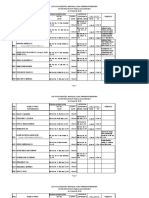

De Lima, et al. v. Gatdula Gr. No. 204528 February 19, 2013

Facts: On 27 February 2012, respondent Magtanggol B. Gatdula filed a Petition for

the Issuance of a Writ of Amparo in the Regional Trial Court of Manila.2 This case

was docketed as In the Matter of the Petition for Issuance of Writ of Amparo of Atty.

Magtanggol B. Gatdula, SP No. 12-127405. It was raffled to the sala of Judge Silvino

T. Pampilo, Jr. on the same day. The Amparo was directed against petitioners Justice

Secretary Leila M. De Lima, Director Nonnatus R. Rojas and Deputy Director

Reynaldo O. Esmeralda of the National Bureau of Investigation Gatdula wanted De

Lima, et al. to cease and desist from framing up Gatdula for the fake ambush

incident by filing bogus charges of Frustrated Murder against Gatdula in relation to

the alleged ambush incident. Instead of deciding on whether to issue the writ, the

judge issued summons and ordered petitioners to file an answer. De Lima, et al.

manifested that a Return, not an Answer, is appropriate for Amparo cases. Judge

Pampilo insisted that since no writ has been issued, return is not the required

pleading but answer. The judge noted that the Rules of Court apply suppletorily in

Amparo cases. He opined that the Revised Rules of Summary Procedure applied and

thus required an Answer. The RTC rendered a Decision granting the issuance of

the Writ of Amparo. Petitioners elevated the case to the SC, assailing the RTC

decision through a petition for review on Certiorari via Rule 45.

Issue: whether or not the filing of answer was appropriate.

Ruling: No. It is the Return that serves as the responsive pleading for petitions for

the issuance of Writs of Amparo. The requirement to file an Answer is contrary to

the intention of the Court to provide a speedy remedy to those whose right to life,

liberty and security are violated or are threatened to be violated. In utter disregard

of the Rule on the Writ of Amparo, Judge Pampilo insisted on issuing summons and

requiring an Answer. The respondents are required to file a Return after the

issuance of the writ through the clerk of court. The Return serves as the responsive

pleading to the petition.24 Unlike an Answer, the Return has other purposes aside

from identifying the issues in the case. Respondents are also required to detail the

actions they had taken to determine the fate or whereabouts of the aggrieved party.

If the respondents are public officials or employees, they are also required to state

the actions they had taken to: (i) verify the identity of the aggrieved party; (ii)

recover and preserve evidence related to the death or disappearance of the person

identified in the petition; (iii) identify witnesses and obtain statements concerning

the death or disappearance; (iv) determine the cause, manner, location, and time of

death or disappearance as well as any pattern or practice that may have brought

about the death or disappearance; and (vi) bring the suspected offenders before a

competent court.25 Clearly these matters are important to the judge so that s/he

can calibrate the means and methods that will be required to further the

protections, if any, that will be due to the petitioner.

You might also like

- SPECIAL POWER OF ATTORNEY SampleDocument2 pagesSPECIAL POWER OF ATTORNEY SampleJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Notice: Republic of The Philippines Supreme CourtDocument6 pagesNotice: Republic of The Philippines Supreme CourtJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Notarial PetitiondfdfdfdDocument3 pagesNotarial PetitiondfdfdfdJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Transpo and TaxDocument32 pagesTranspo and TaxJanus MariNo ratings yet

- 2017 Pds GuidelinesDocument4 pages2017 Pds GuidelinesManuel J. Degyan75% (4)

- GMRCDocument1 pageGMRCJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Masterlist CPA Firms APRIL 30 2018.outputDocument1,602 pagesMasterlist CPA Firms APRIL 30 2018.outputJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Oath of OfficeDocument2 pagesOath of OfficeJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics 2005 2014 Bar QADocument62 pagesLegal Ethics 2005 2014 Bar QAJanus Mari100% (1)

- Yu Vs NLRC June 1993Document10 pagesYu Vs NLRC June 1993Janus MariNo ratings yet

- Case Digest On Atienza V. Brillantes: Manzano Vs SanchezDocument3 pagesCase Digest On Atienza V. Brillantes: Manzano Vs SanchezJanus MariNo ratings yet

- 2015 Bar QuestionsDocument8 pages2015 Bar QuestionsJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Labor Notes 2Document8 pagesLabor Notes 2Janus MariNo ratings yet

- Transpo and TaxDocument32 pagesTranspo and TaxJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Every Saturday Morning Starting June 18Document1 pageEvery Saturday Morning Starting June 18Janus MariNo ratings yet

- Cover PageDocument1 pageCover PageJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Bar Questions 2007Document8 pagesLegal Ethics Bar Questions 2007Janus MariNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Bar Qs 2014Document15 pagesLegal Ethics Bar Qs 2014Janus MariNo ratings yet

- Bank CertificateDocument2 pagesBank CertificateJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics 2005 2014 Bar QA DraftDocument86 pagesLegal Ethics 2005 2014 Bar QA DraftJanus Mari67% (3)

- 2012 Legal Ethics Bar Question and AsnwerDocument18 pages2012 Legal Ethics Bar Question and AsnwerJanus Mari100% (2)

- Bank CertificateDocument2 pagesBank CertificateJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Spec ProDocument20 pagesSpec ProJanus MariNo ratings yet

- USC v. CADocument1 pageUSC v. CAJanus MariNo ratings yet

- AdjustersDocument1 pageAdjustersJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Siguion Reyna, Montecillo & Ongsiako For Petitioner. Morales & Joyas Law Office For Private RespondentDocument3 pagesSiguion Reyna, Montecillo & Ongsiako For Petitioner. Morales & Joyas Law Office For Private RespondentJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Understanding Corporation LawDocument36 pagesUnderstanding Corporation LawJanus Mari100% (1)

- MinutesDocument1 pageMinutesJanus MariNo ratings yet

- Minutes SampleDocument2 pagesMinutes SampleveerabalajiNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Navia v. PardicoDocument1 pageNavia v. PardicoMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Civil Case Set 1 FullDocument13 pagesCivil Case Set 1 FullMG DangtayanNo ratings yet

- Court denies writ of amparo for detained alienDocument9 pagesCourt denies writ of amparo for detained alienBonito Bulan100% (1)

- Petition For Issuance of Writ of Amparo For San Andres Bukid CommunityDocument59 pagesPetition For Issuance of Writ of Amparo For San Andres Bukid CommunityVERA Files100% (1)

- Writ of AmparoDocument15 pagesWrit of AmparoJan Aldrin AfosNo ratings yet

- 2018 Last Minute Tips in Political LawDocument31 pages2018 Last Minute Tips in Political LawGeorge AngelesNo ratings yet

- EthicsDocument5 pagesEthicsChrisNo ratings yet

- The Secretary of National Defense V Manalo (Under Section 11 of Art 2. Consti.)Document4 pagesThe Secretary of National Defense V Manalo (Under Section 11 of Art 2. Consti.)nabingNo ratings yet

- GR No. 249274-CAGUIOADocument10 pagesGR No. 249274-CAGUIOAJoshua SantosNo ratings yet

- Arellano 2018 REMEDIAL LAW LMT - ReviewedDocument48 pagesArellano 2018 REMEDIAL LAW LMT - ReviewedTom SumawayNo ratings yet

- Saez Vs Macapagal-ArroyoDocument15 pagesSaez Vs Macapagal-Arroyovanessa_3No ratings yet

- 14 - in Matter of Petition For Issuance of A Writ of Amparo in Favor of LadagaDocument2 pages14 - in Matter of Petition For Issuance of A Writ of Amparo in Favor of LadagaKriselNo ratings yet

- Rubrico vs. ArroyoDocument2 pagesRubrico vs. ArroyoJoyce Villanueva100% (1)

- Petition for certiorari against writs of amparo and habeas dataDocument3 pagesPetition for certiorari against writs of amparo and habeas dataRachel ChanNo ratings yet

- Gen. Avelino I. Razon, Jr. Et Al. Vs Mary Jean Tagitis GR No. 182498 FULL CASEDocument70 pagesGen. Avelino I. Razon, Jr. Et Al. Vs Mary Jean Tagitis GR No. 182498 FULL CASERhob-JoanMoranteNo ratings yet

- De Lima Et - Al vs. Gatdula Case DigestDocument2 pagesDe Lima Et - Al vs. Gatdula Case DigestDanilo Magallanes SampagaNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. CayananDocument2 pagesRepublic vs. CayananSamuel John CahimatNo ratings yet

- B. Digest Tapuz Vs Del RosarioDocument3 pagesB. Digest Tapuz Vs Del RosarioWhoopi Jane MagdozaNo ratings yet

- Special Proceedings Syllabus (2017)Document13 pagesSpecial Proceedings Syllabus (2017)Lloyd ReyesNo ratings yet

- Final Draft Nupl Amparo For Filing PDFDocument23 pagesFinal Draft Nupl Amparo For Filing PDFJamar KulayanNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Habeas CorpusDocument12 pagesCase Digest Habeas CorpusTata BentorNo ratings yet

- Mison vs Gallegos ruling on writ of amparoDocument2 pagesMison vs Gallegos ruling on writ of amparoral cb100% (1)

- Aquino vs. Enrile: The Ilagan CaseDocument10 pagesAquino vs. Enrile: The Ilagan CaseArvi CalaguiNo ratings yet

- Military Abuse Case Decided by Writ of AmparoDocument2 pagesMilitary Abuse Case Decided by Writ of AmparoTerence ValdehuezaNo ratings yet

- Tapuz V Del Rosario GR No. 182484, 17 June 2008 Brion, J.: FactsDocument1 pageTapuz V Del Rosario GR No. 182484, 17 June 2008 Brion, J.: FactsMav EstebanNo ratings yet

- Gloria Macapagal Arroyo vs. People of The Philippines and The Sandiganbayan G.R. NO. 220598 APRIL 18, 2017Document4 pagesGloria Macapagal Arroyo vs. People of The Philippines and The Sandiganbayan G.R. NO. 220598 APRIL 18, 2017Jenalin FloranoNo ratings yet

- SPECIAL PROCEEDINGS DSLU 2nd PART COMPR EXAM 2ND SEM 2019 2020Document5 pagesSPECIAL PROCEEDINGS DSLU 2nd PART COMPR EXAM 2ND SEM 2019 2020Yralli MendozaNo ratings yet

- SPECIAL PROCEEDINGS Syllabus (2017)Document13 pagesSPECIAL PROCEEDINGS Syllabus (2017)Marlon BalberonaNo ratings yet

- D9 Lucena V ElagoDocument7 pagesD9 Lucena V ElagoJay BarnsNo ratings yet

- PNP officials ordered to find missing engineerDocument346 pagesPNP officials ordered to find missing engineermuton20No ratings yet